Abstract

Aim: The aim of the present study was to explore the associations between the economic, political, sociocultural and physical environments in kindergartens, along with the frequency and variety of vegetables served, and the amount of vegetables eaten. Method: The BRA Study collected data through two paper-based questionnaires answered by the kindergarten leader and pedagogical leader of each selected kindergarten, and a five-day vegetable diary from kindergartens (n = 73) in Vestfold and Buskerud Counties, Norway. The questionnaires assessed environmental factors, and the frequency and variety of vegetables served. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to explore the associations between factors in the kindergarten environments and vegetables served and eaten. Results: Kindergartens that included expenditures for food and beverages in the parental fees served a larger variety of vegetables (p = 0.046). A higher frequency of served vegetables (p = 0.014) and a larger amount (p = 0.027) of vegetables eaten were found in kindergartens where parents paid a monthly fee of 251 NOK or more. Similarly, the amount of vegetables eaten was higher (p = 0.017) in kindergartens where the employees paid a monthly fee to eat at work. Furthermore, a larger amount (p = 0.046) of vegetables was eaten in kindergartens that had written guidelines for food and beverages that were offered. Conclusions: This study indicates that the economic environment in a kindergarten seems to be positively associated with the vegetables served and eaten there. This is of high relevance for public health policy as vegetable consumption is an important factor in reducing the risk of non-communicable diseases.

Keywords: Kindergarten, vegetables, preschool children, BRA Study, environment, Norway, political, economic, sociocultural, physical

Introduction

Vegetable consumption is an important factor in reducing the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer [1]. The inadequate intake of vegetables is a public health problem and can be a contributive factor to increased morbidity [2]. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), only 63% of the European population ate vegetables daily in 2008, and availability was the major determinant of consumption [2]. This highlights the importance of improved access to vegetables in the different daily contexts for both children and adults. Early prevention of NCDs is important and emphasized by health authorities at all levels [3–5]. The national recommendation for adults in Norway is 250 g of vegetables per day [6]. Among Norwegian two- and four-year-olds, the intake is roughly 50–70 g daily [7,8].

Obesity-related behaviors such as dietary intake seem to carry over from childhood into adulthood [9]. Children learn by observing others and their surroundings, they are constantly developing and adapting, and the people and environment that surround them will have influence on their development [10]. Food preferences appear to be more modifiable during early childhood [11]; hence, targeting children’s dietary habits during this period is important. Norwegian kindergartens are institutions for all children in the age group 1–5 years. The kindergartens are regulated by law and have a framework plan for the content and tasks [10]. Formal education is required in order to be employed as a pedagogical or kindergarten leader. In general, kindergartens are open from approximately 7:30 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. from Monday through Friday. Meals are either brought from home (lunch box), provided by the kindergarten or else a combination. There are normative national guidelines for food and meals served in kindergarten, which specify that the kindergarten should serve or provide for at least two meals a day that are in line with national dietary guidelines [12]. According to the guidelines for food and meals, the kindergarten has a responsibility to contribute to teaching children healthy dietary habits [10]. National dietary surveys in Norwegian kindergartens conducted in 2005 and 2011 [13,14] reported low availability of vegetables in the kindergartens. However, with a 91% attendance rate [15] kindergartens have the potential to reach many children and their families.

According to the analysis grid for environments linked to obesity (ANGELO) framework, factors within the kindergarten environment can be characterized as economic (i.e. resources related to buying vegetables), political (i.e. guidelines and rules related to vegetables), sociocultural (i.e. values and behavior related to vegetables) and physical (i.e. factors that can hinder or enable the availability of vegetables) [16]. With regard to economic resources, a review including observational and intervention studies focusing on children aged 4–8 years and using the ANGELO framework, found no results of studies assessing economic factors [17]. As for the political factors, policy recommendations and written guidelines are not necessarily sufficient to ensure adequate nutrition in the child care settings [18]. However, Norwegian kindergarten leaders have previously reported that the two most important factors to secure healthy meals in kindergarten are to follow the national dietary guidelines and include them in their annual plans [12,14]. Finally, regarding the sociocultural and physical factors, a previous study has found positive associations between the sociocultural and physical environments and the mealtime setting in child care services in the Netherlands [19]. In addition, a review conducted by Holley et al. [20] found a positive effect of repeated exposure to increase vegetable intake in children aged 2–5 years, while for social factors the results were contradictory. A small Norwegian qualitative case study found that the physical environment was of great importance for the quality of the food and meals served by the kindergartens [21].

The aim of the present study was to explore the associations between economic, political, sociocultural and physical environmental factors in kindergartens, and the frequency and variety of vegetables served, as well as the amount of vegetables eaten.

Method

Study design and subjects

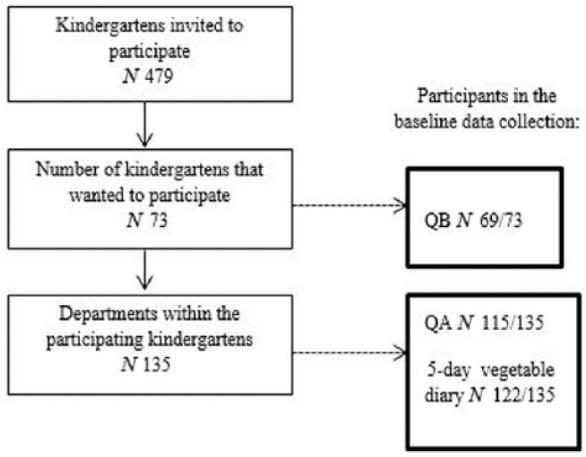

Baseline data from the BRA Study (Barnehage (kindergarten), gRønnsaker (vegetables) and fAmilie (family)) are used in the present study. The BRA Study is a cluster randomized controlled intervention study with an overall aim to improve vegetable intake among preschool children (3–5 years at baseline) through changing the food environment and dietary practices in the kindergarten and at home. More specifically, the aim is to increase the daily frequency of vegetable intake, the variety of vegetables eaten over a month and the daily amount of vegetables consumed. The target group for the BRA Study is preschool children born in 2010 and 2011, attending public or private kindergartens in the counties of Vestfold and Buskerud, Norway. In fall and winter 2014/2015, all 479 public and private kindergartens in these two counties were invited by letter to participate in the study, of which 73 kindergartens accepted (15.2% response rate). Within the 73 kindergartens, departments with children born in 2010 or 2011 were eligible for the study and 135 departments agreed to participate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants.

Data were collected using several instruments: 1) a paper-based questionnaire (Questionnaire A) assessing frequency and variety of vegetables served was answered by pedagogical leaders in 115 of the 135 departments (86%); 2) a paper-based questionnaire (Questionnaire B) assessing the kindergarten environment was filled in by the kindergarten leaders, where 69 of 73 leaders responded (95%); and 3) the amount of vegetables eaten was assessed using a five-day vegetable diary completed by employees in 122 of the 135 departments (90%) (Figure 1). Few instruments have focused solely on factors affecting vegetables served and the frequency and variety of vegetables served to preschool children, and no instrument was identified suiting the purpose of this study. Therefore, modified items from statements and questions used in the last national dietary survey in kindergartens [14] and the last dietary survey among Norwegian two-year-olds [7] were included in the BRA questionnaires. The questions are not tested for reliability or validity.

Data collection

(1) Vegetables served and eaten: Questionnaire A and five-day vegetable diary

Questionnaire A was piloted among 11 pedagogical leaders. Small adjustments were made after feedback. In March 2015, Questionnaire A was mailed to all the participating kindergartens (n = 73) and returned in a pre-paid envelope. One mailed reminder was sent with the questionnaire enclosed.

Frequency of served vegetables for lunch and the afternoon meal was assessed through two separate questions: “How often does your department offer vegetables for lunch/the afternoon meal?”. The response alternatives were on a seven-point scale ranging from “five days a week” to “never”. The variety of vegetables served for lunch and afternoon meal was assessed through two separate questions: “How often does your department offer these vegetables for lunch/afternoon meal?”. A total of 12 vegetable alternatives were given with the same response categories as mentioned above.

For the five-day vegetable diary, all kindergartens were given a digital kitchen scale (capacity = 5 kg, graduation = 1 g). One employee from each department received face-to-face instruction on how to measure and report the amount of vegetables eaten in the five-day vegetable diary. The employees were asked to weigh the vegetables before each meal and to weigh the leftovers after the meal, and to report the number of children and employees eating at each meal. They were encouraged to report five consecutive days in order to assess a typical week. Data from the lunch and the afternoon meals are presented as amount of vegetables consumed per person per day. A protocol was developed on how to interpret missing data. The two main types of missing data were the number of children and employee eating, and whether the vegetables were “ready-to-eat” or not. If the diaries had data from 50% of the meals regarding number of children and employee eating, then a mean number was calculated to replace missing data. Diaries with data of less than 50% were registered as missing. Diaries with missing data for “Are the vegetables ready-to-eat?” were assumed to be “ready-to-eat”.

(2) Factors in the kindergarten environment: Questionnaire B

Questionnaire B was piloted with two kindergarten leaders. Only minor revisions were made after the pilot test. Most of the questions were from the last national dietary survey in Norwegian kindergartens [14]. In this paper, questions describing four aspects of the kindergarten environment were used: the economic, political, sociocultural and physical environments. In all questions where a five-point Likert scale was used, the scale is collapsed into three categories: “agree, neither, disagree” or “small, neither, large”, and two of “small/neither, large”. The economic environment was assessed through five questions as shown in Table III, the political environment through four questions as shown in Table IV, while the sociocultural environment was evaluated through two questions shown in Table VI. In Table VI the factor that covers “to what degree different mealtime pedagogics are emphasized in the training of new employees” is based on eight items summed from one to eight and thereafter grouped into “low” (0–3), “average” (4–5) and “high” (6–8).

Table III.

Factors in the economic food environment in the kindergarten, and vegetables served or eaten (n = 66).

| Variation | Frequency | Amount | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | |

| 1) Food supplies are covered through: maximum parents’ fees | Yes 11 | 10 (8;11.8) | 5.3 (5;9) | 12 | 36.2 (31;52) | |||

| No 55 | 7.7 (6;10) | .046a | 6.3 (5;7.5) | .945a | 54 | 36.8 (24.3;50.7) | .690a | |

| Additional parental payment to cover expenses for food and beverages | Yes 59 | 7.8 (6;10) | 6.2 (5;7.5) | 58 | 36.8 (24;51.3) | |||

| No 7 | 10 (8.5;11.8) | .045a | 6.3 (5.1;9) | .552a | 8 | 36.2 (32.3;44.5) | .651a | |

| 2) Additional parental payment to cover expenses for food and beverages | < 250 NOKd 29 | 8 (6;10) | 5 (3.5;7) | 30 | 27 (15;57.7) | |||

| > 251 NOKd 36 | 8 (7;10) | .450a | 6.8 (6;8) | .014a | 34 | 39.9 (31.8;50.7) | .027a | |

| 3) Freedom within the food budget: I can use the budget as I wish | Agree 29 | 9 (7;10) | 7 (5.5;9) | 30 | 45.2 (29.5;57.7) | |||

| Neither 12 | 9 (7;10.5) | 5.8 (4.5;6.8) | 11 | 41.8 (27.5;46.2) | ||||

| Disagree 25 | 7 (5;9) | .033c | 6.2 (4;7.3) | .166c | 25 | 31.3 (15.2;37) | .010c | |

| There are rules for how I distribute the budget | Agree 27 | 8 (6.8;10) | 6 (5;7) | 25 | 36.5 (24.5;47.9) | |||

| Neither 12 | 6.8 (6;7.9) | 6.2 (2.5;7.1) | 13 | 42.7 (24.3;46.3) | ||||

| Disagree 26 | 9 (7;10) | .248c | 7 (5;8) | .291c | 27 | 36.4 (27.5;53.5) | .759c | |

| The budget covers the kind of food we want to offer | Agree 36 | 8 (6;10) | 6.1 (5;7.3) | 35 | 41.8 (29.5;53.6) | |||

| Neither 5 | 10 (7;12) | 5 (4;6.8) | .668c | 5 | 39.8 (14.9;45.8) | |||

| Disagree 24 | 7.7 (6.8;10) | .409c | 6.6 (3.3;8.5) | 25 | 31.8 (23.7;42.7) | .150c | ||

| I am free to use other budgets on food | Agree 40 | 8.8 (6.6;10) | 6.1 (5;8) | 38 | 36.4 (24.1;51.6) | |||

| Neither 13 | 7.7 (6;9.6) | 7.1(5;8) | 13 | 33.4 (30.8;42.6) | ||||

| Disagree 13 | 7 (6.5;10) | .500c | 6 (5;6.8) | .672c | 15 | 41.8 (27.1;55.8) | .508c | |

| 4) Employees pay a monthly fee for food and beverages | Yes 53 | 8 (7;10) | 6.5 (5.3;8) | 52 | 39.9 (30.3;51.5) | |||

| No 9 | 6 (5;9) | .079a | 4 (2.5;7.3) | .113a | 10 | 27 (9;30.8) | .017a | |

| 5) Monthly fee for employees (food and beverages) | < 250 NOKd 37 | 8.5 (7;10) | 6.3 (5;8) | 36 | 36.7 (25.5;48.5) | |||

| > 251 NOKd 13 | 7.5 (6.5;9) | .375a | 7 (6;7.8) | .527a | 13 | 40 (36.4;51.3) | .287a | |

Asymp. Sig. (two-tailed) Mann–Whitney U test.

Tukey’s hinges.

Asymp. Sig. Kruskal–Wallis H test.

Norwegian kroner.

Note: < 3 missing within the variation and frequency data; < 4 missing within the amount data.

Table IV.

Factors in the political food environment in the kindergarten, and vegetables served or eaten (n = 66).

| N | Variation | Frequency | Amount | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (percentiles)b | p-value | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | ||

| 1) Written guidelines: food and beverages brought from home | Yes 42 | 7.5 (6;10) | .197a | 5.8 (4;7) | 42 | 38.9 (24.3;51.6) | ||

| No 22 | 9 (7;11) 8 |

7.5 (6.3;8) | .001a | 22 | 36.2 (29.5;46.3) | .562a | ||

| Food and beverage that’s offered | Yes 55 | (6.5;10) | 6 (5;8) | 54 | 38.9 (27;51.6) | |||

| No 9 | 9 (7;9) | .635a | 6.8 (6.3;7.8) | .373a | 10 | 32.8 (9;40) | .046a | |

| Mealtime setting | Yes 41 | 7.5 (6;9) | 6 (4.3;8) | 41 | 39.8 (29.4;51.6) | |||

| No 21 | 9 (7;11) | .072a | 6.3 (5.5;7.8) | .479a | 21 | 31.2 (24;41.8) | .091a | |

| 2) Who has developed the guidelines: the entire staff group? | Yes 19 | 8 (6.6;10) | 6 (5.5;7.5) | 18 | 39.2 (30.8;51.3) | |||

| No 47 | 8 (6.3;10) | .955a | 6.3 (4.6;7.9) | .645a | 48 | 36.2 (23.9;49.9) | .536a | |

| 3) Knowledge of national guidelines | Yes 61 | 8 (6.5;10) | 6.3 (5;8) | 59 | 36.4 (25.6;48.4) | |||

| No 5 | 8 (7;11) | .653a | 6 (5.5;7) | .827a | 7 | 51.3 (41.3;72.1) | .075a | |

| 4) To what degree are the national guidelines used in developing own guidelines? | Small 7 | 10 (9;11) | 6 (5.3;6.6) | 8 | 42 (25.6;72.1) | |||

| Neither 12 | 9 (6.8;9.5) | 6.8 (4.8;9) | 13 | 38.5 (36;51.3) | ||||

| Large 44 | 7.7 (6;10) | .259c | 6.2 (5;7.9) | .576c | 41 | 36.5 (24.3;47.9) | .568c | |

Asymp. Sig. (two-tailed) Mann–Whitney U test.

Tukey’s hinges.

Asymp. Sig. Kruskal–Wallis H test.

Note: < 4 missing within variation and frequency data; < 4 missing within the amount data.

Table V.

Factors in the physical food environment in the kindergarten, and vegetables served and eaten (n = 66).

| N | Variation | Frequency | Amount | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (percentiles)b | p-value | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | ||

| 1) Barriers for using vegetables: I do not buy vegetables because they are too expensive | Agree 16 | 8.5 (7.3;10) | 7.3 (6.7;9) | 17 | 31.8 (23.7;41.8) | |||

| Neither 13 | 7 (6;8) | 5 (3;6) | 14 | 43.1 (27.1;49) | ||||

| Disagree 37 | 8.5 (6;10) | .335c | 6.2 (5;7.8) | .008c | 35 | 36.4 (27.4;53.2) | .404c | |

| I do not buy vegetables because they do not look fresh | Agree 10 | 8 (6.7;10) | 6 (5.5;9) | 11 | 44.7 (33.2;48.5) | |||

| Neither 15 | 7.8 (7;9.3) | 7.1 (6.7;8) | 15 | 36.7 (28.3;48.6) | ||||

| Disagree 41 | 8 (6;10) | .979c | 6 (4;7.3) | .070c | 40 | 34.7 (24.2;51.2) | .819c | |

| I do not buy vegetables because they are hard to keep fresh | Agree 17 | 7 (7;10) | 6 (5.5;7.3) | 18 | 36.2 (26.9;44.7) | |||

| Neither 10 | 7.4 (6;9) | 6.2 (5;7.3) | 11 | 29.5 (19.3;44.9) | ||||

| Disagree 39 | 8.5 (6.3;10) | .821c | 6.3 (5;8) | .961c | 37 | 39.3 (29.4;54.9) | .219c | |

| I do not use vegetables because they are too time consuming to use in my daily cooking | Agree 7 | 6 (5.5;8.5) | 6.2 (4.3;8) | 7 | 25.7 (26;42.9) | |||

| Neither 5 | 8 (5.5;10) | 7.3 (5.5;7.8) | 5 | 31.8 (17.3;49) | ||||

| Disagree 54 | 8.3 (7;10) | .465c | 6.2 (5;8) | .895c | 54 | 37.6 (27;51.3) | .799c | |

| I do not use vegetables because they are difficult to include in my daily cooking | Agree 3 | 11 (9.5;11.5) | 7.8 (6.9;8.9) | 3 | 31.3 (21.2;40) | |||

| Neither 3 | 5.5 (5.3;6.8) | 2.5 (1.5;6.3) | 3 | 27 (22.2;38.1) | ||||

| Disagree 60 | 8 (6.5;10) | .093c | 6.2 (5;7.6) | .341c | 60 | 36.8 (27;51.3) | .658c | |

| 2) How many staff have the primary responsibility to: | ||||||||

| Determine the food and beverage offer | 1 person: 9 | 8.5 (7;10.5) | 6 (5;9) | 17 | 33.4 (27;51.3) | |||

| > 1 person: 47 | 7.8 (6;10) | .235 | 6.3 (5;7.3) | .383 | 49 | 36.7 (24.3;48.8) | .753 | |

| Plan the food and beverage offer | 1 person: | 8.5 (6.3;10.5) | 6.3 (4.6;8.5) | 18 | 30.4 (24.1;54.8) | |||

| > 1 person: 47 | 8 (6.5;10) | .555 | 6.2 (5;7.5) | .681 | 48 | 37.8 (27.5;49.9) | .481 | |

| Order food and beverages | 1 person: 15 | 10 (7.2;11.3) | 5.3 (5;6.8) | 13 | 29.4 (16.3;45.8) | |||

| > 1 person: 51 | 7.7 (6;9.8) | .090 | 6.4 (5.1;8) | .263 | 53 | 37 (27.9;50.7) | .249 | |

| Prepare the food | 1 person: 43 | 8 (6;10) | 6 (4.1;7.9) | 43 | 33.4 (23.9;44.2) | |||

| > 1 person: 23 | 8.5 (7.2;10) | .341 | 6.4 (5.8;7.6) | .462 | 23 | 44.7 (31;51.5) | .091 | |

| 3) Dedicated kitchen staff | Yes 11 | 10 (7.7;11.3) | 5.3 (5;7) | 9 | 31.8 (29.5;54.8) | |||

| No 55 | 7.8 (6;10) | .078a | 6.3 (5;8) | .262a | 57 | 36.7 (26.9;48.8) | .661a | |

Asymp. Sig. (two-tailed) Mann–Whitney U test.

Tukey’s hinges.

Asymp. Sig. Kruskal–Wallis H test.

Note: 0 missing within variation and frequency data; 0 missing within the amount data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS® Statistics Version 24.0. Data on frequency and variety (Questionnaire A), in addition to data on amount of vegetables served (five-day vegetable diary), were aggregated to the kindergarten level as the data on the kindergarten environment were collected at an institutional level and not at the department level (Questionnaire B). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normality. Due to data not being normally distributed, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to test for differences between groups.

Results

According to Statistics Norway, there were a total of 568 [15] kindergartens in Vestfold and Buskerud Counties in 2014 (Table I), of which 41% were public and 59% were private kindergartens. In the BRA Study, 45% were public and 55% were private kindergartens. Kindergartens in Vestfold and Buskerud had a mean of 12.5 full-time equivalents, and a mean of 4.1 employees with the formal education to work as a pedagogical or kindergarten leader. In the kindergartens in the BRA Study, the means were 13.9 full-time equivalents and 5.9 with formal education. Furthermore, 47% of kindergartens in these counties were registered as five-a-day fruit and vegetable kindergartens compared with 41% of the BRA kindergartens. Only full-time public and private kindergartens were included due to these being the most common child care institutions in Norway. Therefore, the invitation to participate was sent to 479 of the 568 kindergartens.

Table I.

Descriptive data of the kindergartens in the BRA Study and the kindergarten population in Vestfold and Buskerud counties.

| Kindergartens in the BRA Study (N = 69)c |

Kindergartens in Vestfold and Buskerud counties (N = 568)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| Number of kindergartens (percent) | Number of kindergartens (percent) | |

| Public kindergartens | 31 (44.9) | 235 (41.4) |

| Private kindergartens | 38 (55.1) | 333 (58.6) |

| Five-a-day-kindergartensb | 28 (41.1) | 266 (46.8) |

| Mean + SD | Mean | |

| Full-time equivalent | 13.9 + 6.4 | 12.5 |

| Full-time equivalent educated as kindergarten teacher | 5.9 + 3.1 | 4.1 |

Statistics Norway (2014), includes all kindergartens in Vestfold and Buskerud, including those that did not meet the criteria.

Five-a-day kindergartens is a concept created by the Norwegian Fruit and Vegetable Marketing eBoard and provides supporting material to the kindergartens for the promotion of fruit and vegetable consumption.

Based on answers from the kindergarten leader.

SD: standard deviation.

The number of kindergartens providing data from the pedagogical leader (Questionnaire A) and the kindergarten leader (Questionnaire B) was 66, while 66 kindergartens had data from the kindergarten leader (Questionnaire B) and the five-day vegetable diary. The number of kindergartens with data from all three sources (Questionnaire A, Questionnaire B and five-day vegetable diary) was 63 (86% of the 73 kindergartens).

Vegetables served and eaten

The median variety of served vegetables was eight per month, the median frequency of vegetables served was 6.3 times per week and the median intake of vegetables consumed per person per day was 36 g (Table II). A higher frequency of vegetables served was found in kindergartens where children consumed 30.1 g vegetables or more per day, compared to those kindergartens where children consumed 30 g or less per day (Table II).

Table II.

The dependent variables: variation, frequency and amount of vegetables served in the kindergartens in the BRA Study (n = 66).

| Median (percentiles)a | Normality testb

p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variation per month | 8 (6.5;10) | .098 | |

| Frequency per week | 6.3 (5;8) | .005 | |

| Amount per person per day (g) | 36.4 (25.6;48.9) | .045 | |

| Amount per person per day (g) | |||

| < 30 g | 30.1–59 g | 60 g > | |

| N | 23 | 33 | 7 |

| Variation median (percentiles)a | 8 (5.5;9.5) | 7.8 (6.7;10) | 10 (7.7;10.5) |

| p-value | .352 | ||

| Frequency median (percentiles)a | 5 (2.3;7.1) | 6.8 (6;8) | 6.8 (5.5;7) |

| p-value | .021 | ||

Tukey’s hinges.

Shapiro–Wilk test.

Statistics Norway (2014), includes all kindergartens in Vestfold and Buskerud, including those that did not meet the criteria [22].

Five-a-day kindergartens is a concept created by the Norwegian Fruit and Vegetable Marketing eBoard and provides supporting material to the kindergartens for the promotion of fruit and vegetable consumption.

Based on answers from the kindergarten leader.

Children are attending kindergarten five days a week – frequency given in the table is for times per week.

Associations between the kindergarten environment and vegetables served and eaten

In the economic environment, three out of nine factors were associated with the variety of vegetables served, one out of nine factors was associated with the frequency of vegetables served and three out of nine factors were associated with the amount of vegetables eaten (Table III). Kindergartens with food and beverages covered by a parental fee had a larger variety of vegetables served per month. However, the variety was also larger in the seven kindergartens that did not ask for any additional payment from the parents to cover food and beverage expenses. In kindergartens where parents paid an additional amount of >251 NOK to cover food supplies, a higher frequency of vegetables served and a larger amount of vegetables consumed were observed. In kindergartens where the leaders agreed that they could use the budget as they wished, a larger amount of vegetables consumed was observed compared to kindergartens where leaders answered “neither” or “disagree”. Those who answered “agree” or “neither” to the same question had a larger variety of vegetables compared to those who answered “disagree”. In the kindergartens where the employees paid a monthly fee for food and beverages, a larger amount of vegetables was consumed (Table III).

For the political environment, one out of six factors was associated with the frequency of vegetables served, and one out of six factors was associated with the amount of vegetables eaten (Table IV). In kindergartens that had written guidelines for food and beverages offered, the children consumed a larger amount of vegetables. However, kindergartens with “written guidelines for food and beverages brought from home” had lower frequency of vegetables served. For the physical environment, one out of 10 factors was associated with the frequency of vegetables served. Frequency of served vegetables was highest among those who “agreed” to the statement, “I do not buy vegetables because they are too expensive”, compared to those that “disagreed” or answered “neither” (Table V). No significant associations were found with the sociocultural environment (Table VI).

Table VI.

Factors in the sociocultural food environment in the kindergarten, and vegetables served and eaten (n = 66).

| Variation | Frequency | Amount | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | N | Median (percentiles)b | p-value | |

| 1) To what degree do new employees learn how to interact with the children in mealtime situations? | Low: 14 | 8 (6.5;9.6) | 6 (4;7.3) | 17 | 36.4 (26.9;44.7) | |||

| Average: 15 | 7.7 (6;8.8) | 6.3 (5.3;7) | 15 | 36.7 (28.3;53.7) | ||||

| High: 34 | 8.8 (6.7;11) | .287c | 6.4 (5;8) | .813c | 34 | 37.5 (24.3;51.3) | .777c | |

| 2) To what degree do you think… | ||||||||

| you need to improve the practical part regarding meals, food and beverages in your kindergarten? | Small/neither: 48 | 8 (6.8;10) | 6.3 (5;7.9) | 49 | 36.5 (27;51.6) | |||

| Large: 18 | 7.3 (5.5;10) | .386a | 6.1 (4;8) | .708a | 17 | 36.7 (20.5;42.7) | .281a | |

| you are competent to guide the employees in what a healthy diet for children is? | Small/neither: 25 | 8 (7;10) | 6 (4.3;8) | 26 | 36.5 (26.9;47.9) | |||

| Large: 41 | 8 (6;10) | .952a | 6.3 (5;7.3) | .638a | 40 | 36.7 (25.3;54.9) | .646a | |

| it’s important for you to guide the employees in what a healthy diet for children is? | Small/neither: 13 | 8 (6.5;9) | 6 (4;8) | 12 | 33.6 (20.8;36.8) | |||

| Large: 53 | 8 (6.6;10) | .871a | 6.3 (5;7.3) | .872a | 54 | 39.6 (27;51.6) | .130a | |

Asymp. Sig. (two-tailed) Mann–Whitney U test.

Tukey’s hinges.

Asymp. Sig. Kruskal–Wallis H test.

Note: < 3 missing within variation and frequency data; < 1 missing within the amount data.

Discussion

This study indicates that more factors within the economic environment were important for the vegetables served and eaten in the kindergartens than factors in the political, physical and sociocultural environments.

The economic environment

The Norwegian government has established a maximum parental fee, independent of whether the kindergarten is under public or private ownership [23]. However, most kindergartens ask for additional payment to cover expenses for food and beverages [14]. This was also shown for 59 out of 66 kindergartens in our study. In line with previous research [14], our results showed that having a larger food budget or perceiving to have budgetary freedom contributed to kindergartens buying and serving more vegetables. Kindergartens with more than NOK 251 in additional payments had a larger frequency of vegetables served and a higher amount of vegetables eaten compared to those with additional payment of less than NOK 251. Unexpectedly, those kindergartens that did not ask for such additional payment had a larger variety in vegetables served compared to those that did ask for additional payment. This may indicate that it is not only the economic resources that matter when buying and serving vegetables. Our results showed that in 53 out of 62 kindergartens, the employees paid a monthly fee for food and beverages, and a larger amount of vegetables was eaten. The higher amount of vegetables eaten may be explained by adults eating with the children, thus contributing to a larger average amount of vegetables eaten. Another explanation might be the positive effect of modelling [20], or by children eating more when the staff eat together with them [19].

For the associations found in the economic environment, one may conclude that increasing the additional payment for food might be a good strategy. On the other hand, this strategy might increase social inequalities by lower socioeconomic groups opting for kindergartens with a lower additional payment for food. Taking into consideration experience from other Nordic countries, the Finnish kindergarten setting is quite unique [24] with both nutrition-specific guidelines and all meals included in the maximum parental fee [25]. Still, research points to low vegetable intake among children in kindergartens in Finland [24,26]. These findings can imply that vegetable consumption may also be affected by factors other than the economy [24,25]. Freedom when setting up the food budget was also associated with a larger variety of vegetables served and a larger amount of vegetables eaten. An explanation for this might be that the kindergarten leaders participating in this study are more personally interested in providing healthy food and this budgetary freedom enables them to act upon it.

The political environment

In the present study, having written guidelines for meals served in the kindergartens was positively associated with vegetable consumption. This is in line with the national survey, where more fresh vegetables were served in kindergartens with written guidelines for the mealtime setting [14]. However, a review conducted in 2011 found that four out of 11 studies explored guidelines and recommendations related to the environment affecting nutrition and food served in child care settings [18]. Moreover, two of these found an insufficient intake of vegetables and only one of the four found an adequate serving of fruit and vegetables, despite having food-specific recommendations, policies or written guidelines to follow [18]. We also found associations indicating a higher frequency of vegetables served in kindergartens without written guidelines for food and beverages brought from home. This might be explained by a lack of need for such guidelines in kindergartens that serve a higher frequency of meals and, thus, also vegetables. This hypothesis was tested, and we found that kindergartens serving meals more frequently, compared to those kindergartens with food brought from home, also served vegetables more frequently (data not shown).

The physical environment

Previous studies have shown that availability is positively associated with children’s consumption of vegetables [20,25,27]. This study assessed the physical environment through barriers for serving vegetables in kindergarten, and, unexpectedly, those that agreed to the statement “I do not buy vegetables because they are too expensive” had the highest frequency of serving vegetables. A potential explanation might be that the Norwegian population is more concerned about eating healthily than the associated costs. However, the costs are also an important factor [28]. A Norwegian case study found that the physical structures, such as who is organizing and planning the meals, were important factors for the food and meals provided by the kindergarten [21], but in our study we did not find an association with the number of people involved in various parts of this process. The physical environment was assessed through three questions, as shown in Table V. The item pool used to assess barriers was composed of modified versions of statements used in an American study among parents of preschool children [29]. For the question regarding “How many have the primary responsibility to…” in Table V, the number of persons for each task was collapsed into “one person” or “more than one person”. In this study, the physical environment has not measured the availability of vegetables, but rather the barriers to serving vegetables and how many employees are responsible for planning and organizing the food.

The sociocultural environment

Contrary to previous research [19,20,27], we did not find any significant associations between the sociocultural environment and vegetables served and eaten. In this study, data were collected at a higher institutional level compared to previous studies [19,20,27]. Moreover, different methodologies when assessing this environment may also have contributed to such discrepancies. In the present study we assessed this environment by questionnaires, but others have assessed this environment through, for example, direct observations [19]. In addition, previous environmental studies have measured other factors in this environment, such as staff behavior, supervision practice and food serving style [19], nutrition education and support for healthy eating [30], and parenting styles and practices [27].

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study was conducted in an understudied age group and context. Furthermore, the sample of kindergartens represented in this study was almost the same share of public, private and five-a-day kindergartens as the total kindergarten population in the two participating counties. Information about vegetable consumption and the environment was collected with three instruments and answered by staff working at different levels in the kindergarten, giving a more holistic dataset.

However, the sample of kindergartens presented in this study might have had a greater interest in food and nutrition or been more engaged in projects and/or research participation. The measurement instruments were piloted, but not tested for reliability and validity. The amount of vegetables eaten was collected by a five-day vegetable diary, which could be filled in by anyone working in the department. This could have impacted the consistency of how the data were reported. Additionally, the amount of vegetables weighed after the meal did not include vegetables that were left on the children’s plates or that had fallen onto the floor. This might have contributed to an overestimation of the amount of vegetables eaten. Moreover, when adults eat the vegetables served, they potentially eat larger portions compared to the children, which contributes to a higher amount of vegetables eaten in total. The questionnaires used were primarily based on items used in the last national dietary survey in kindergartens [14], ensuring comparability across studies in Norway. However, since the ANGELO framework was not applied in developing the questionnaire, limited aspects of each environment were covered.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the economic environment in kindergartens seems to be positively associated with the vegetables served and eaten in those kindergartens. Also, the political environment seems to be important for the servings and intake of vegetables in kindergartens. This is of high relevance for public health policy as vegetable consumption is an important factor in reducing the risk of NCDs. The lack of associations within the sociocultural and physical environments may be explained by factors being assessed at a more distal level of the organization. Furthermore, studies of how environmental factors interact or are mediated by one another may also be necessary in order to better understand their influence on the variety, frequency and intake of vegetables.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study and the research team members.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (228452/H10), with supplementary funds from the Throne Holst Nutrition Research Foundation, University of Oslo, Norway.

References

- [1]. World Health Organization. Global status report on noncomunicable diseases 2014: “attaining the nine global noncomunicable diseases targets; a shared responsibility”. Geneva: World Health Organization, Geneva 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [2]. OECD. Determinants of health. In: Health at a glance: Europe 2012, pp. 49–64, OECD Publishing, 49–64, OECD Publishing. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [3]. European Commision. Green paper, “Promoting healthy diets and physical activity: a European dimension for the prevention of overweight, obesity and chronic disease”. Brussels: Commision of the European Communities, 2005, http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/nutrition/documents/nutrition_gp_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Norwegian Ministries. The Norwegian Action Plan on Nutrition (2007–2011): recipe for a healthier diet. Oslo: Norwegian Ministries, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. World Health Organization. 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: WHO, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Norwegian Directorate of Health. Norwegian recommendations on diet, nutrition and physical activity [in Norwegian]. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Kristiansen AL, Lande B, Andersen LF. Småbarnskost 2007 – dietary habits among 2-year-old children in Norway [in Norwegian]. Oslo: University of Oslo, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Hansen LB, Myhre JB, Andersen LF. UNGKOST 3 – dietary habits among 4-year-olds [in Norwegian]. Oslo: University of Oslo, 2016, https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/rapport-ungkost-3-landsomfattende-kostholdsundersokelse-blant-4-aringer-i-norge-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, et al. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review. Maturitas 2011;70:266–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. Guidelines for the kindergartens content and tasks [in Norwegian]. Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Education And Research, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annu Rev Nutr 1999;19:41–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Norwegian Directorate of Health. Guidelines for food and meals in the kindergarten. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Norwegian Directorate of Health and social affair. Food and meals in the kindergarten – survey among kindergarten leaders and pedagogical leaders. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Norwegian Directorate of Health. Meals, physical activity and environmental health care in kindergartens 2012. Report no. IS-0345. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Statistics Norway. Kindergartens, 2016: final numbers. Oslo: Statistics Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 1999;29:563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Johnson BJ, Hendrie GA, Golley RK. Reducing discretionary food and beverage intake in early childhood: a systematic review within an ecological framework. Public Health Nutr 2015;19:1684–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Larson N, Ward DS, Neelon SB, et al. What role can child-care settings play in obesity prevention? A review of the evidence and call for research efforts. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1343–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Gubbels JS, Kremers SP, Stafleu A, et al. Child-care environment and dietary intake of 2- and 3-year-old children. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010;23:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Holley CE, Farrow C, Haycraft E. A systematic review of methods for increasing vegetable consumption in early childhood. Curr Nutr Rep 2017;6:157–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Aadland EK, Holthe A, Wergedahl H, et al. Physical factors impact on the food and meal offer in the kindergarten – a case study. Nordic Early Childhood Education Research Journal 2014;8:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Statistics Norway. Kindergartens, 2016: final numbers. Oslo: Statistics Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [23]. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. Parental fee. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Dahl T, Jensberg H. Diet in schools and kindergartens and the significance for health and learning – an overview. Norden 2011; 534, http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:700700/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- [25]. Ray C, Määttä S, Lehto R, et al. Influencing factors of children’s fruit, vegetable and sugar-enriched food intake in a Finnish preschool setting – preschool personnel’s perceptions. Appetite, Elsevier, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Erkkola M, Kronberg-Kippila C, Kyttala P, et al. Sucrose in the diet of 3-year-old Finnish children: sources, determinants and impact on food and nutrient intake. Br J Nutr 2009;101:1209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Brug J, Kremers SP, Lenthe F, et al. Environmental determinants of healthy eating: in need of theory and evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 2008;67:307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Norwegian Directorate of Health. Utviklingen i Norsk kosthold [Development in the Norwegian diet 2016]. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Baranowski T, Beltran A, Chen T-A, et al. Psychometric assessment of scales for a Model of Goal Directed Vegetable Parenting Practices (MGDVPP). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Ammerman AS, Ward DS, Benjamin SE, et al. An intervention to promote healthy weight: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) theory and design. Prev Chronic Dis 2007;4:A67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]