Abstract

Objectives:

To identify temporal patterns of patient-reported trismus during the first year post-radiotherapy, and to study their associations with maximal interincisal opening distances (MIOs).

Design:

Single institution case series.

Setting:

University hospital ENT clinic.

Participants:

One hundred ninety six subjects who received radiotherapy (RT) for head and neck cancer (HNC) with or without chemotherapy in 2007–2012 to total dose of 64.6/68 Gy in 38/34 fractions, respectively. All subjects were prospectively assessed for mouth-opening ability (Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ), and MIO) pre-RT and at 3, 6, and 12 months after RT.

Main outcome measures:

Correlations between temporally robust GTQ-symptoms and MIO as given by Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Pr); temporally robust GTQ-symptom domains as given by factor analysis; rates of trismus with respect to baseline by risk ratios (RRs).

Results:

Four temporally robust domains were identified: Eating (3–7 symptoms), Jaw (3–7), Pain (2–5), and Quality of Life (QoL, 2–5), and included 2–3 persistent symptoms across all post- RT assessments. The median RR for a moderate/severe (>2/>3) cut-off was the highest for Jaw (3.7/3.6) and QoL (3.2/2.9). The median Pr between temporally robust symptoms and MIO post-radiotherapy was 0.25–0.35/0.34–0.43/0.24–0.31/0.34–0.50 for Eating/Jaw/Pain/QoL, respectively.

Conclusions:

Mouth-opening distances in HNC patients post-RT can be understood in terms of associated patient-reported outcomes on trismus-related difficulties. Our data suggest that a reduction in MIO can be expected as patients communicate their mouth-opening status to interfere with private/social life, a clinical warning signal for emerging or worsening trismus as patients are being followed after RT.

Introduction

Trismus occurs in almost every second head and neck cancer (HNC) survivor after receiving radiotherapy 1–2, with mouth-opening ability decreasing most rapidly within the first year after completed oncological treatment (post-RT) 3–4. Mouth-opening ability is not always routinely assessed in post-RT follow-up 5, and several study-specific definitions and cut-off values for trismus have been developed 4. Currently, the gold standard trismus definition is represented by a maximal interincisal opening distance (MIO) ≤35 mm 4, 6, 7. However, knowledge on how such trismus measures relate to the impairment from the patient’s perspective is limited, but is needed to better understand the clinical significance of mouth-opening measurements 1, 2.

Trismus leads to eating and speech difficulties, impaired oral hygiene, altered facial expression, pain, reduced nutrition, and has considerable negative impact on quality of life 5, 8, 9. Also, the presence of trismus in HNC patients may interfere with proper physical and dental examinations, thereby limiting possibilities to identify a relapse. Prevention of trismus is important since once trismus occurs, it is difficult to treat and often becomes permanent 3–5. Johnson et al 10 introduced a trismus-specific patient-reported outcome instrument, the Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ), which successfully has been used to quantify trismus in HNC following RT 10–12. Provided temporal information on the GTQ domains and MIO, relationships between temporally robust GTQ-items and MIO could be identified to widen possibilities to monitor and prevent trismus post-RT in HNC.

The aim of this work is to investigate temporal patterns of radiation-induced trismus at various time points within the first year after RT for HNC with the ultimate goal to increase the general understanding and monitoring of this injury. More specifically, the association between temporally robust trismus domains of GTQ and mouth-opening ability, as assessed by MIO, was studied.

Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations

Patient data was collected from electronic case records and questionnaires and reviewed only by members of the responsible research team. The local ethics board approved the study and written informed consent was received from all participants.

Study design and participants

This prospective cohort study was conducted between 2007 and 2012 at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. Details on the cohort have previously been described 11. In brief, the study population inclusion criteria were consecutively recruited HNC patients treated with RT with/without chemotherapy but not with surgery for tumours of the nasopharynx, oral cavity (floor of mouth, gum, soft palate, or tongue), oropharynx (base of tongue or tonsil), lip, nasal cavity, salivary gland, sinuses, or tumour colli. Patients had to be able to read and understand the questionnaires and were not to have undergone palliative treatment, being edentulous, or in poor general health. For the purpose of this work patients were in addition not included if participating in an associated intervention study using a structured exercise program nor if having MIO≤35 mm at baseline. In total, 215 subjects who had been treated to 64.6/68 Gy in 38/34 fractions, respectively, fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Trismus assessments

Three sources of information regarding trismus, all assessed at baseline and at 3/6/12 months post-RT, were considered for the present study. Two patient-reported outcome instruments were used: the GTQ 10, and the HNC-specific module of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) 13. The GTQ includes 21 items on eating limitations, jaw-related problems, muscular tension, pain and impact on quality of life (QoL), generally with a one-week-recall period and with a 1–5 answering classification (1: not at all; 5: very severe) 10. The HNC-specific module of EORTC QLQ-H&N35 13 includes 35 items classified from 1 to 4, of which the two items “Did you experience pain in your jaw” and “Did you have difficulties opening your mouth” were included here. The Likert scale answering categories of both patient-reported outcome instruments are translated into equally distributed scores between 0–100 (0/100 indicates the lowest/highest symptom severity). An overview of all considered GTQ and EORTC QLQ-HN35 items, and their answering categories are given in Table S1. MIO was measured with a ruler as the distance between the edges of the incisors of the mandible and the maxilla (mm accuracy), and with the subject in an upright position 11.

Statistical analysis

Temporally robust symptom domains were identified from our factor analysis methodology, which was previously applied to group radiation-induced patient-reported items for prostate cancer 14. A detailed description of this approach can be found in the Appendix 14–19. Exploratory- followed by confirmatory factor analysis was carried out in R using the Psych 20 and Lavaan 21 packages with the comparative fit index used as a measure of factor model agreement.

Items in an identified temporally robust domain were correlated with MIO using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Pr). For the GTQ items with seven answering categories, categories 2 and 3 were combined into one category corresponding to a “mild” symptom severity; answering categories 6 and 7 were combined into a “very severe” answering category. Since GTQ items are measured on a categorical scale and MIO on a continuous scale, five GTQ-corresponding MIO categories were defined: 1: >50mm; 2: 41–50mm; 3: 36–40mm; 4: 26–35mm, and 5: <26mm. In particular, MIO≤35 mm (corresponding to our MIO categories 4 and 5) is recommended as the clinical cut-off level for trismus 4, 6. Similarly, the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 items were correlated with a re-categorized MIO, but for these analyses MIO categories 4 and 5 were combined into one since the answering categories of the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 ranged from 1 to 4. Relative risks (RRs) and related 95% confidence intervals were calculated relative to baseline for all GTQ items, the two EORTC QLQ-H&N35 items, as well as for MIO. All symptoms, and MIO were analysed for at least moderate cut-off (answering category >2), and at least severe cut-off (answering category >3).

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 196 subjects presented with complete patient-reported outcome data and MIO information at baseline, and were retained for analysis (Table 1). The majority of these subjects were men (72%), treated with chemo-RT (70%), and their mean±standard deviation age was 60±11 years. Almost two thirds were former or current smokers (62%). Primary tumours were predominantly located in the oropharynx (66%), and more specifically in the tonsil (47%) or the base of tongue (13%). T-stage was typically ≥T2 (73%); N-stage was predominantly N2 or N3 (57%). These characteristics remained stable in rate over time, although the number of subjects with complete data decreased to 186/152/149 at 3/6/12 months post-RT, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for all included subjects.

| Baseline | Post-RT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| N=196 | N=186 | N=152 | N=149 | |

| Age [years] | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD |

| 60±11 | 59±11 | 60±11 | 60±11 | |

| Sex | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| Female | 55 (28) | 54 (29) | 39 (26) | 39 (26) |

| Male | 141 (72) | 132 (71) | 112 (74) | 110 (74) |

| Smoker | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| never | 67 (34) | 63 (34) | 56 (37) | 55 (37) |

| former | 76 (39) | 73 (39) | 55 (36) | 56 (38) |

| current | 45 (23) | 42 (23) | 34 (22) | 33 (22) |

| missing | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 7 (5) | 5 (3) |

| Tumour site | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| Nasopharynx | 12(6) | 12(6) | 8 (5) | 8 (5) |

| Oral cavity, tot. | 24 (12) | 24 (13) | 23 (15) | 20 (13) |

| floor of mouth | 6 (3) | 7 (4) | 6 (4) | 4 (3) |

| soft palate | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) |

| tongue | 13 (7) | 13 (7) | 13 (9) | 11 (7) |

| unspecified | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Oropharynx, tot. | 129 (66) | 122 (66) | 96 (63) | 98 (66) |

| base of tongue | 26 (13) | 24 (13) | 16 (11) | 19 (13) |

| oropharynx | 10 (5) | 9 (5) | 8 (5) | 8 (5) |

| tonsil | 93 (47) | 89 (48) | 72 (47) | 71 (48) |

| Tumour colli | 21 (11) | 20 (11) | 15 (10) | 15 (10) |

| Other, total | 10 (5) | 8 (4) | 10 (7) | 8 (5) |

| gum | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| lip | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| nasal cavity | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| parotid | 5 (3) | 4 (2) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) |

| sinus | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| T-stage | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| 0 | 21 (11) | 20 (11) | 15 (10) | 15 (10) |

| 1 | 33 (17) | 29 (16) | 27 (18) | 23 (15) |

| 2 | 74 (38) | 73 (39) | 58 (38) | 61 (41) |

| 3 | 37 (19) | 36 (19) | 25 (17) | 26 (17) |

| 4 | 31 (16) | 28 (15) | 26 (17) | 24 (16) |

| N-stage | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| 0 | 52 (27) | 51 (27) | 43 (28) | 42 (28) |

| 1 | 31 (16) | 27 (15) | 23 (15) | 22 (15) |

| 2 | 93 (47) | 91 (49) | 74 (49) | 72 (48) |

| 3 | 20 (10) | 17 (9) | 12 (8) | 13 (9) |

| 4 | - | - | - | - |

| M-stage | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) |

| 0 | 196 (100) | 186 (100) | 152 (100) | 149 (100) |

Abbreviations: SD= standard deviation; T/N/M= tumour/node/metastasis according to the TNM classification of tumours

Trismus assessments

For the GTQ scores, the population mean± standard deviation of all 21 items increased from 10±6 to 18–26±9–11 post-RT (Table S2). Correspondingly, the population mean±standard deviation scores for the two EORTC QLQ-HN35 items, increased from 14±1 to 23–30±3–5. For both assessment methods, the higher scores, indicating more trismus-related problems, were attained at 3 months post-RT. For MIO, the population mean±standard deviation was 49±8 mm at baseline, and 39±9 mm/40±8 mm/41±9 mm at 3/6/12 months post-RT. This corresponded to a % drop of 20%/18%/16%, respectively, compared to baseline. For the five defined MIO categories, this resulted in an increase from an averaged category value of 1.7±0.8 to 2.7–3.1±1.1–1.2 with higher values indicating smaller MIOs. Corresponding rates of trismus according to MIO≤35 mm were 5% at baseline and 52/38/28% at 3/6/12 months post-RT.

Relative change in symptom occurrence over time with respect to baseline

The occurrence of at least moderate symptom cut-off (answering category >2) increased for all GTQ items at some follow-up time (Table S3). Fifteen of these items presented with increased RR at all time points (GTQ1–5, 7–13, 19–21) of which the RRs for GTQ10, 13, 19 were in the higher end (RR=2.6–4.9; p≤0.05). The EORTC QLQ-HN35 item 40 presented with an increased RR at all time points (RR=1.8–2.9; p≤0.05). For at least severe symptom cut-off (answering category >3), there were seven GTQ items with increased RR at all time points (GTQ1, 3–5, 8–9, 11) of which the RRs for GTQ1, and 22 were in the higher end (RR=2.6–4.9; p≤0.05). For this symptom cut-off, none of the EORTC QLQ-HN35 items presented with significantly increased RR at any time point. Having MIO≤35 mm was up to nine times more common in subjects during follow-up as compared with their baseline MIOs (RR=9.2/6.7/4.9; p<0.0001 at 3/6/12 months), and having MIO≤40 mm was six times more common at all three follow-up times (RR=6.4/6.0/5.6; p<0.0001).

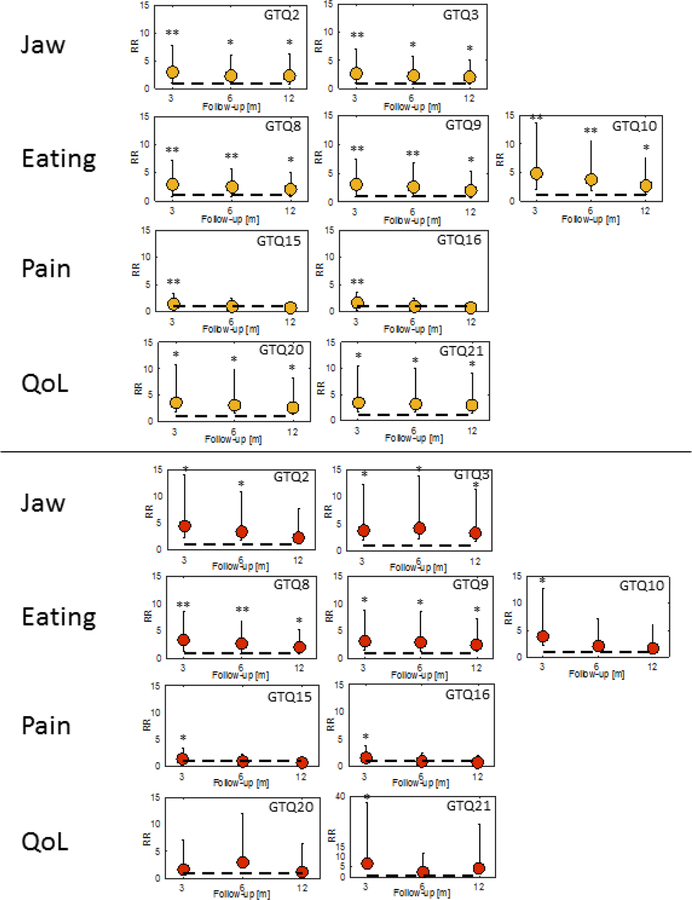

GTQ symptom domains

The best-fitting models were obtained for five-factor solutions at baseline (comparative fit index: 0.93; Table S4), and at 3 and at 12 months post-RT (comparative fit index: 0.96 and 0.88, respectively), and for a four-factor solution at 6 months post-RT (comparative fit index: 0.97). The four symptom domains identified at each follow-up included items related to jaw function (Jaw), eating ability (Eating), pain (Pain), and QoL (Tables 2 and S5). These temporally robust symptom domains were at most modestly correlated with each other (Pr≤0.65), with the stronger correlations occurring most frequently between Jaw and QoL (Pr=0.56–0.64). For Jaw, GTQ2 and 3 were identified at each follow-up. Similarly, GTQ8–10 remained as temporally robust symptoms for Eating, GTQ15 and 16 for Pain, and GTQ20 and 21 for QoL. The RRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for these nine temporally robust symptoms are illustrated for at least a moderate, and at least a severe symptom cut-off in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Symptom domains of the GTQ items within the first year post-radiotherapy (RT) with related symptom-group importance of each included item.

Note: Temporally stable symptoms are highlighted in white.

| Baseline | Post-RT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months (N=196) | 3 months (N=186) | 6 months (N=152) | 12 months (N=149) | ||||

| Item phrasing | Importance | Item phrasing | Importance | Item phrasing | Importance | Item phrasing | Importance |

| Jaw-related problems (Jaw) | |||||||

| 1. Jaw fatigue/stiffness | 1 | 1. Jaw fatigue/stiffness | 4 | 1. Jaw fatigue/stiffness | 4 | ||

| 2. Jaw aches/pain | 3 | 2. Jaw aches/pain | 3 | 2. Jaw aches/pain | 5 | 2. Jaw aches/pain | 1 |

| 3. Pain moving jaw (opening mouth/chewing) | 4 | 3. Pain moving jaw (opening mouth/chewing) | 2 | 3. Pain moving jaw (opening mouth/chewing) | 2 | 3. Pain moving jaw (opening mouth/chewing) | 3 |

| 4. Problems opening mouth wide/taking a bite | 7 | 4. Problems opening mouth wide/taking a bite | 3 | ||||

| 5. Pain/soarness in jaw muscles | 2 | 5. Pain/soarness in jaw muscles | 1 | 5. Pain/soarness in jaw muscles | 1 | ||

| 6. Problems jawning | 6 | ||||||

| 7. Jaw noices | 2 | ||||||

| 19. Current mouth opening limitation | 5 | ||||||

| Eating limitations (Eating) | |||||||

| 4. Problems opening mouth wide/taking a bite | 5 | ||||||

| 6. Problems jawning | 7 | ||||||

| 8. Problems eating solid food | 1 | 8. Problems eating solid food | 3 | 8. Problems eating solid food | 1 | 8. Problems eating solid food | 1 |

| 9. Problems putting food in mouth | 3 | 9. Problems putting food in mouth | 4 | 9. Problems putting food in mouth | 2 | 9. Problems putting food in mouth | 3 |

| 10. Problems eating soft food | 2 | 10. Problems eating soft food | 1 | 10. Problems eating soft food | 3 | 10. Problems eating soft food | 2 |

| 11. Problems biting off | 4 | 11. Problems biting off | 2 | 11. Problems biting off | 4 | ||

| 19. Current mouth-opening limitation | 6 | ||||||

| Pain-related problems (Pain) | |||||||

| 14. Current severity of facial pain | 3 | 14. Current severity of facial pain | 3 | ||||

| 15. Intensity of worst pain | 1 | 15. Intensity of worst pain | 2 | 15. Intensity of worst pain | 2 | 15. Intensity of worst pain | 2 |

| 16. Averaged intensity of pain | 2 | 16. Averaged intensity of pain | 1 | 16. Averaged intensity of pain | 1 | 16. Averaged intensity of pain | 1 |

| 17. Facial pain interfearing with social/leisure/family activities | 4 | ||||||

| 18. Facial pain affecting work ability | 5 | ||||||

| Quality of life issues related to mouth-opening difficulties (QoL) | |||||||

| 7. Jaw noices | 5 | ||||||

| 17. Facial pain interfearing with social/leisure/family activities | 4 | ||||||

| 18. Facial pain affecting work ability | 3 | ||||||

| 20. Mouth-opening limitation changing work ability | 2 | 20. Mouth-opening limitation changing work ability | 1 | 20. Mouth-opening limitation changing work ability | 2 | 20. Mouth-opening limitation changing work ability | 2 |

| 21. Mouth-opening limitation interfering with private activities | 1 | 21. Mouth-opening limitation interfering with private activities | 2 | 21. Mouth-opening limitation interfering with private activities | 1 | 21. Mouth-opening limitation interfering with private activities | 1 |

Abbreviations: GTQ= Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire; RT= radiotherapy

Figure 1.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for the temporally robust Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ) items across 3/6/12 months after radiotherapy relative to baseline for ≥moderate (upper; orange dots), and ≥severe symptom cut-off (lower; red dots) severity.

Note: ** p≤0.0001; * p≤0.05

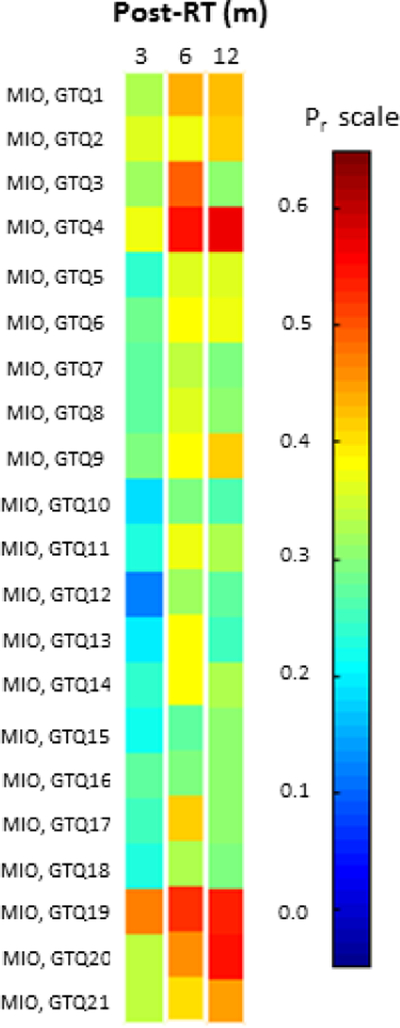

Relationships between temporally robust GTQ symptoms and MIO post-RT

For the temporally robust symptoms of any GTQ domain, the correlations with MIO over all follow-up times were at most moderate (Pr=0.19–0.55; Table 3; Figure 2). The Jaw and QoL domains presented with the higher correlations post-RT (Pr=0.31–0.49 and 0.34–0.55, respectively). The QoL items GTQ20 and 21 had the overall highest correlations with MIO post-RT (3/6/12 months post-RT: 0.34/0.46/0.55 and 0.34/0.40/0.45, respectively).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients (Pr) between GTQ items and MIO categories within the first year post-RT.

Note: Moderate correlations marked in white (Pr=0.36–0.57); temporally robust symptoms (Table 2) enclosed in boxes.

| Baseline | Post-RT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 months | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| GTQ item number | Symptom domain | N=196 Pr | N=186 Pr | N=152 Pr | N=149 Pr |

| 1 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.43 | |

| 2 | Jaw | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.41 |

| 3 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.31 | |

| 4 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.57 | |

| 5 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.36 | |

| 6 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.37 | |

| 7 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.30 | |

| 8 | Eating | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.31 |

| 9 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.42 | |

| 10 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.26 | |

| 11 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.33 | |

| 12 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.27 | |

| 13 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.25 | |

| 14 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.33 | |

| 15 | Pain | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| 16 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.31 | |

| 17 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.31 | |

| 18 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.30 | |

| 19 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.53 | |

| 20 | QoL | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| 21 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.45 | |

Abbreviations: GTQ= Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire; MIO= maximal interincisal opening; RT= radiotherapy

Figure 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Pr) between each of the 21 Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire (GTQ) items and MIO at 3/6/12 months post-radiotherapy (post-RT).

Note: The color coding on the left hand side follows that of the Pr scale on the right hand side.

Discussion

Temporally robust GTQ symptoms and their relationships with MIO

We identified four temporally robust patient-reported-based trismus symptom domains and illustrated their associations with objectively measured mouth-opening distances throughout the first year after radiotherapy (RT) for head and neck cancer (HNC). Temporally robust item rates for moderate symptom severity were up to five-fold increased post-RT compared with baseline. Among the items factoring in under Jaw, Eating, Pain, or QoL, the strongest correlations with mouth-opening distances were found for trismus affecting private and professional activities (social/leisure/family/work).

Several studies have stressed the importance of anchoring the investigated cut-off value on MIO with clinically significant trismus 1, 2, 6, 22. In our study, the overall strongest correlation with MIO was observed for either of the two temporally robust QoL items (GTQ20 and 21). Using objective mouth-opening measurements in mm and the Liverpool oral rehabilitation questionnaire, Scott et al. investigated the relationship between restricted mouth-opening and subjective functioning in 100 HNC patients who had received surgery with/without RT 22. Although not reported as their main finding, their data suggest that mouth-opening distances correlate with difficulty opening mouth affecting social life (|Pr|=0.40; median follow-up=16 months). Several studies confirm that restricted mouth-opening interferes with QoL and activities of daily living 2, 3, 7, 23. With respect to the specific impact on private activities, Lee et al. conducted a cross-sectional study in 112 HNC patients treated with RT (with/without chemotherapy), where they found that the scores for the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 item Social contact were significantly worse in trismus- than in non-trismus patients as defined by the 35 mm cut-off. Also, for a subset of the patients included in our study, Johnson et al. recently presented results concerning the impact of trismus on health-related QoL 27. The highest-dysfunction-indicating items of both the GTQ and the short-form 36 health survey (SF-36) reflected private/professional activities and role limitation due to physical problems, respectively. Unfortunately, neither of the latter studies presents correlations with mouth-opening distances. Still these data, together with our results, points towards a possibly stronger relationship between trismus and limitations in social life than previously recognized.

Relationships between mouth-opening distances and perceived physical problems due to trismus have been addressed previously 1, 6. A recent study by Wetzels et al found that mouth-opening inability at one year post-RT in patients with oral cancer (RT with/without surgery) was moderately correlated (|Pr|=0.55) with a self-reported trismus item: “During the past week, have you experienced problems with opening your mouth wide?” 1. In the context of our study, their item would correspond to GTQ item 19 or EORTC QLQ-H&N35 item 40, which presented with correlation coefficients of the same range (|Pr|=0.53 and 0.56 at one year post-RT, respectively). Although Wetzels et al measured maximum mouth-opening extra-orally 1, it is interesting to note that the correlation coefficients for our temporally robust QoL items with MIO were also in this range and peaked at one year post-RT (|Pr|=0.45–0.55). Furthermore, the RR was higher for the GTQ item 19 (up to four-fold increase) than for the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 item 40 (up to three-fold increase), and for both items the RR was typically higher at three months post-RT than at one year post-RT. Together, these findings suggest that mouth-opening problems within the first year after RT may be easier to detect using five-category scales (mild-very severe) than four-category scales (mild-severe). Our results are also in accordance with previous research, which shows that radiation-induced trismus recovers to some extent during the first year after treatment 1, 3, 4.

Comparison with original GTQ domains from various perspectives

The three GTQ domains originally identified by Johnson et al. in 2012 (eating limitations/jaw-related problems/muscular tension: 4/6/3 items) 10 were not consistent across the time points investigated in the current dataset. It has, however, previously been demonstrated that symptoms may reallocate to a different domain over time 24. Our Jaw domain included three or more of the original jaw-related domain’s six items at each follow-up time. Our Eating domain was also similar to the original eating limitations domain with three of the original four items being present at all follow-up times. In contrast, the three items of the original muscular tension domain were present only at baseline (two items) and at one year post-RT (all three items) in our data. The 78 HNC patients included for the development of GTQ all had MIO≤35mm, which was confirmed at follow-up post-RT; our case series included patients with clinically confirmed trismus as well as non-trismus patients. Furthermore, two factor analysis approaches were used; a fixed factor-loading threshold (≥0.40)/scree-plots/total variance to decide the final number of factors/symptom domains in the Johnson study 10 and a comparative fit index-driven exploratory/confirmatory factor analysis approach here. Considering cohort- and analysis differences, it is not surprising that the number of identified domains and included number of items or our domains vary from the original GTQ domains. All these aspects will be considered in future work to further develop GTQ.

Limitations

When interpreting our results, it should be kept in mind that data was taken from one hospital with the treatment approaches in use during the studied period of time. The patients constituted a fairly homogenous group of individuals with respect to age, ethnicity, and sex and were recruited within a limited geographical region. Our results concern dentulous HNC patients, and may not be fully applicable to edentulous patients or specific cancer diagnoses. Compared to other studies, our reported trismus rates were also in the higher end and peaked typically at three months post-RT. This can to some extent be explained by focusing on trismus in a cohort including patients treated with RT alone (surgery causes lower trismus rates 6), and also that the 3 months-post-RT assessment point might capture remaining early radiation-induced reactions. Finally, our investigated categories of MIO can be criticized to cover too well functioning mouth-opening ability (category indicating the highest dysfunction for MIO<26 mm), which in the objective setting has been denoted moderate impairment 4. Normal mouth-opening ability, on the other hand, was in our analyses set to MIO>50mm, which also is a matter of discussion with MIOs from 30–35 mm 4 up to 60 mm 25 reported to capture the normal state. Our patient-reported outcome driven categories with the associated perceptions of various degrees of symptom severity are, therefore, a compromise between these assumptions, and in addition, our data did not allow for studying a lower MIO cut-off as at most nine patients presented with MIO<26 mm post-RT.

Clinical applicability of the study

The strengths of our study are a relatively large unselected cohort including subjects consecutively treated for HNC and an objective symptom grouping method applied to prospectively collected data on longitudinally monitored trismus. The correlations between MIO and perceived physical problems due to trismus in our case series are in accordance with other studies, which further improve reliability and applicability of our findings. Specific questions on mouth-opening status interfering with social/private life can be used as a screening tool to assess clinically meaningful radiation-induced trismus post-treatment.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that a reduction in MIO can be expected as patients communicate their mouth-opening status to interfere with private/social life after RT for HNC. Bearing in mind the importance of timely management of trismus 3–5, our results can, therefore, assist in detecting early trismus warning signs. Evidence for structured exercise programs with jaw mobilising devices to give lasting improvements of trismus-related symptoms are emerging 12, 26, and offering such interventions as patients indicate mouth-opening problems may help to ameliorate this condition for future patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients who provided data for this study, as well as the clinical staff involved in patient care and data collection. This work was supported by the King Gustaf V Jubilee Clinic Cancer Foundation in Göteborg (C.O.), the Swedish state under the ALF agreement in Göteborg (C.F.), the Swedish Society for Medical Research (C.O.) and Varian Corporation (M.T.). The Assar Gabrielsson Foundation (C.O.), the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship Research & Charity (C.O.) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

This work was in part presented at the European SocieTy for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) annual meeting 35, 29 April-03 May, 2016 in Turin, Italy.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Wetzels JW, Merkx MA, de Haan AF et al. (2014) Maximum mouth opening and trismus in 143 patients treated for oral cancer: a 1-year prospective study. Head Neck 36, 1754–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee LY, Chen SC, Chen WC, Huang BS et al. (2015) Postradiation trismus and its impact on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Surg Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 119, 187–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamstra JI, Dijkstra PU, van Leeuwen M et al. (2015) Mouth opening in patients irradiated for head and neck cancer, a prospective repeated measures study. Oral Oncol 51, 548–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapidis AD, Dijkstra PU, Roodenburg JL et al. (2015) Trismus in patients with head and neck cancer, epipathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Otalyrongal 40, 516–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensadoun RJ, Riesenbeck D, Lockhart PB et al. (2010) A systematic review of trismus induced by cancer therapies in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 18, 1033–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijkstra PU, Huisman PM, Roodenburg JL (2006) Criteria for trismus in head and neck oncology. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 35, 337–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner F, Evans J, Marsh R et al. (2015) Mouth opening and trismus in patients undergoing curative treatment for head and neck cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 44, 292–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkstra PU, Kalk WW, Roodenburg JL (2004) Trismus in head and neck oncology, a systematic review. Oral Oncol 40, 879–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sciubba JJ, Goldenberg D (2006) Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 7, 175–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J, Carlsson S, Johansson M et al. (2012) Development and validation of the Gothenburg Trismus Questionnaire. Oral Oncol 48, 730–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauli N, Johnson J, Finizia C et al. (2013) The incidence of trismus and long-term impact on health-related quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol 52, 1137–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pauli N, Andréll P, Johansson M et al. (2015). Treating trismus, A prospective study on effect and compliance to jaw exercise therapy in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 37, 1738–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Tollesson E et al. (1994) Development of a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessments in head and neck cancer patients. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Acta Oncol 33, 879–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thor M, Olsson CE, Oh JH, Petersen SE et al. (2015) Relationships between dose to the gastro-intestinal tract and patient-reported symptom domains after radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 54, 1326–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farnell DJ, Mandall P, Anandadas C et al. (2010) Development of a patient-reported questionnaire for collecting toxicity data following prostate brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol 97, 136–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao C, Hanlon A, Zhang Q et al. (2013) Symptom clusters in patients with head and neck cancer receiving concurrent radiotherapy. Oral Oncol 49, 360–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabrigar LR, MacCallum RC (1999) Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods 4, 272–99 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis, Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling 6, 1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor R (1990) Interpretation of the correlation coefficient. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography 6,35–9 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revelle W (2014) Procedures for personality and psychological research Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosseel Y (2012) An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Software 48, 21–36 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott B, Butterworth C, Lowe D et al. (2008) Factors associated with restricted mouth opening and its relationship to health-related quality of life in patients attending a Maxillofacial Oncology clinic. Oral Oncol 44, 430–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson J, Johansson M, Rydén A et al. (2015) Impact of trismus on health-related quality of life and mental health. Head Neck 37, 1672–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim E, Jahan T, Aouizerat BE et al. (2009) Changes in symptom clusters in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer 17, 1383–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mezitis M, Rallis G, Zachariades N (1989) The normal range of mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47, 1028–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauli N, Svensson U, Karlsson T et al. (2016) Exercise intervention for the treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer – a prospective two-year follow-up study. Acta Oncol Mar 3,1–5 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.