Abstract

Introduction

Numerous studies have focused on nonpharmacological interventions on cognitive function and the effects of cognitive function on daily living. However, effects of behavior change techniques that promote physical, cognitive, and social activities on cognitive function and incident dementia in the elderly are yet to be elucidated. In this study, we aimed to design a single-blind, randomized controlled trial to study dementia prevention effects of behavior change techniques, using an accelerometer and a newly developed daily activity booklet in community-living older adults.

Methods

The study cohort comprised 5390 individuals aged 65 years and older who were randomized into one of the following three groups: accelerometer group (n = 1508), accelerometer and daily activity booklet group (n = 1180), or a control group (n = 2702; vs. accelerometer group [n = 1509] vs. accelerometer and daily activity booklet group [n = 1193]). Incident dementia was diagnosed based on the Japanese Health Insurance System data. The participants without dementia at baseline, who are diagnosed with dementia over a 36-month follow-up period, are considered to have incident dementia. The participants of the accelerometer group were asked to wear the accelerometer everyday and visit a site having data readers to download the accelerometer data every month. The subjects of the booklet group were requested to not only wear the accelerometer but also record the physical, cognitive, and social activities. The participants receive a feedback report from the data of the accelerometer and booklet.

Discussion

The study has the potential to provide the first evidence of effectiveness of the self-monitoring tools in incident dementia. In case our trial results suggest a delayed dementia onset upon self-monitoring interventions, the study protocol will provide a cost-effective and safe method for maintaining a healthy cognitive aging.

Keywords: Dementia, Activity, Randomized controlled trial, Prevention, Elderly

Highlights

-

•

We aim to study dementia prevention effects of behavior change techniques.

-

•

The study may shed light on the effect of self-monitoring in dementia prevention.

-

•

The findings may provide a safe method for maintaining a healthy cognitive aging.

1. Background

Nonpharmacological interventions that address cognitive function and the impact of cognitive function on daily living have been widely studied for cognitive decline. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Nagamatsu et al. [1] showed that targeted physical activity and/or cognitive training are effective strategies to promote both cognitive and functional brain plasticity in older adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies demonstrated low-to-moderate inverse associations of physical activity with cognitive decline and dementia, with overall relative risk estimates of 0.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55-0.76) and 0.86 (95% CI 0.76-0.97), respectively [2].

Despite the established benefits of physical activity, 30% of the world's population fails to reach the levels of physical activity recommended for health benefits [3]. This low adherence to regular physical activity may be attributed to several factors. A systematic review revealed six major themes of barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation: social influences such as valuing interaction with peers and encouragement from others; physical limitations including concerns about falling and comorbidities; competing priorities; access difficulties; personal benefits of physical activity; motivation and beliefs such as apathy, inefficacy, and maintaining habits [4]. Therefore, engagement with physical activities can be influenced by behavioral factors such as motivation and personal beliefs, as well as environmental factors including availability of public transport and exercise venues. The most commonly reported behavior change techniques to improve physical activity are self-monitoring, goal setting, tailoring, relapse prevention training, feedback, and strategies to increase motivation and self-efficacy. Currently, there are several available technical devices that aim to monitor and promote changes in physical activity (PA) behavior [5]. Such devices include pedometers, accelerometers, activity trackers, heart rate monitors, and smartphone applications. These devices can be used separately or in combination with a computer, a smartphone, or an iPad when self-monitoring PA (PA self-monitoring technologies). Compared to PA, fewer behavior change techniques for cognitive and social activities have been reported, although numerous studies have identified the relationships between these activities and health outcomes [6], [7].

We showed that the probability of dementia is significantly lower in individuals who had an active lifestyle including daily conversation, driving a car, shopping, and field work or gardening using longitudinal observational data [8]. However, effects of behavior change techniques in physical, cognitive, and social activities on cognitive function improvement and incident dementia in the elderly are not clear. In this study, we developed a self-monitoring tool to facilitate daily physical, cognitive, and social activities. We designed a single-blind RCT to determine dementia prevention effects of behavior change techniques, including an accelerometer and a daily activity booklet, in community-living older adults. To determine the effect of the newly developed daily activity booklet, we stratified and conducted the trial as separate self-monitoring interventions with accelerometer and accelerometer plus daily activity booklet. To integrate and analyze these trials, the same assessment and follow-up methods were conducted in both trials.

2. Methods

The Self-Monitoring Activity Program study has been conducted as a single-center and single-blind RCT and is currently funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The Human Research Ethics Committees of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology have approved this study. The study is registered with the University hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (identification number: UMIN000035405).

2.1. Participants and power analysis

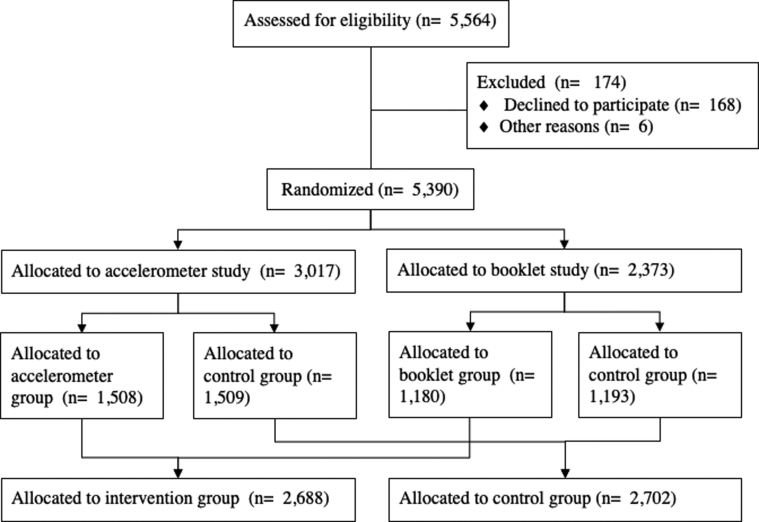

The study cohort comprised 5390 older adults aged 65 years and older; the participants were randomized into one of the following three groups: accelerometer group (Accel group; n = 1508), accelerometer and daily activity booklet group (Booklet group; n = 1180), or a control group (n = 2702; vs. Accel group; n = 1509, vs. Booklet group; n = 1193) (Fig. 1). Participants were recruited via direct mail and public relations. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. The power analysis we used is based on the proportion of incident dementia. We based our sample size calculation on the cumulative incidence of dementia in our previous study [9]. Enrollment of 5390 participants provided 80% power to detect a 33% between-group difference in the cumulative incidence of dementia, with a two-sided α level of 0.05. The 33% between-group difference was deemed realistic on the basis of previously published data [10].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the participant flow.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the Self-Monitoring Activity Program study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Aged 65 years and older | Dementia diagnosis |

| Japanese speaker | Inability to use accelerometer or booklet due to cognitive decline |

| Adequate visual and auditory acuity to complete neuropsychological testing | Any significant systemic illness or unstable medical condition |

| Willingness to participate in the entirety of study | Sever disability |

| Willingness and ability to provide written informed consent |

2.2. Procedures

At the start of the intervention and control periods, baseline measurements in relation to neuropsychological testing, blood sample collection, completion of questionnaires, and assessments of physical fitness were obtained. The Japanese National Health Insurance and Later-Stage Medical Care systems were checked on a monthly basis to track newly reported cases of incident dementia (Alzheimer's disease [AD] or other dementia subtypes). Dementia was diagnosed by medical doctors according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [11]. The participants without dementia at baseline who were later diagnosed with dementia over a 36-month follow-up period were considered to have incident dementia.

2.3. Randomization

The individuals were assigned to each study group using a stratified randomization protocol. The participants were stratified by intervention, accelerometer, and accelerometer plus a daily activity booklet interventions, before being randomly assigned to one of the following three groups: Accel group, Booklet group, or control group.

2.4. Intervention

The participants of the Accel group were asked to wear the accelerometer everyday and visit one of the nine sites of Tokai city monthly, where data readers are available to download the accelerometer data. The participants received a feedback report of physical activity, which included monthly average walking speed, step number, consumed calories, and daily achievement levels for a predetermined target of walking speed and step number.

The subjects of the Booklet group were requested to not only wear the accelerometer but also record the activity that includes physical, cognitive, and social activities. The items of physical activity were walking, light exercise, gardening or field work, sports, housekeeping, and others. The cognitive activities included reading books or newspapers, writing a diary, using a personal computer, solving puzzles or playing board games, having a hobby with cognitive stimulation, and others. The items of social activity are taking care of something, having a job or doing volunteer work, conversation, shopping or outdoor activities, participating in community meetings, and others. The participants filled the booklets upon implementation of these activities everyday and received a monthly feedback report of the activity changes.

2.5. Outcome measures

2.5.1. Primary outcome measure: incidence of dementia

In Japan, all adults aged ≥65 years have public health insurance comprising one of the following criteria: health insurance for employed individuals (Employees’ Health Insurance), national health insurance for unemployed and self-employed individuals aged 65–74 years (Japanese National Health Insurance), or health care for individuals aged ≥75 years (Later-Stage Medical Care) [12]. In the present research, the participants were tracked monthly for newly incident dementia (AD or other dementia subtypes) during the follow-up period as recorded by the Japanese National Health Insurance and Later-Stage Medical Care systems.

2.5.2. Baseline assessments

Dementia results from numerous factors that work together over a long period. Demographic variables, chronic medical conditions, psychosocial factors, physical performance, and cognitive function are associated with dementia incidence in older persons [13], [14]. In this study, all multivariate models included the following covariates unless otherwise specified: age at enrollment, sex, educational level, current smoking status, chronic medical illnesses, depressive symptoms, comfortable walking speed, and cognitive impairment. The presence of the following self-reported chronic medical illnesses was entered into the models: heart disease, pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. The walking speed was measured in seconds using a stopwatch. The participants walked five times on a flat and straight surface at a comfortable walking speed, and the average walking speed was calculated. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale [15]. We used the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology-Functional Assessment Tool (NCGG-FAT), an iPad application, to conduct cognitive screening [16], [17]. The NCGG-FAT includes the following domains: (1) memory (wordlist memory-I [immediate recognition] and word list memory-II [delayed recall]); (2) attention (a tablet version of the Trail Making Test, TMT-part A); (3) executive function (a tablet version of the TMT-part B), and (4) processing speed (a tablet version of the Digit Symbol Substitution Test). The participants were given approximately 20 minutes to complete the battery. The NCGG-FAT has been shown to have high test–retest reliability, moderate-to-high criterion-related validity [16], and predictive validity [17] among community-dwelling older persons. Well-trained study assistants conducted the assessments of cognitive functioning using community facilities, such as community halls. Before the study began, all staff received training from the authors regarding the protocols for administering the assessments. Potential participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) were identified after reviewing available clinical, neuropsychological, and laboratory data at meetings involving study neurologists, geriatricians, and neuropsychologists, as previously described [18]. In brief, the MCI participants were independently recruited using the NCGG-FAT, which has two memory tasks: tests of attention and executive function, and a processing speed task. Using the established criteria [19], we diagnosed MCI in individuals who exhibited cognitive impairment but were functionally independent in terms of basic daily life activities. For all cognitive tests, we used established standardized thresholds in each corresponding domain for defining impairment in population-based cohorts comprising community-dwelling older persons (scores > 1.5 standard deviations below the age- and education-specific means). We used the Mini-Mental State Examination to measure global cognitive function [20].

2.6. Statistical analyses

Student's t test and Pearson's chi-squared test were used to calculate the differences in the baseline characteristics between the groups. We calculated the cumulative dementia incidence during the follow-up, and intergroup differences were estimated using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models are used to analyze associations among the Accel, Booklet, and control groups. After adjustment for age and sex for the first model, we used a multiple adjustment model adjusted for demographic variables, primary diseases, lifestyle, psychological and physical performance, and cognitive function variables as possible confounding factors. Adjusted hazard ratios for dementia incidence and their 95% CIs were estimated. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v.25.0 (IBM Japan, Tokyo). Statistical significance threshold was set at P < .05.

3. Discussion

Several large-scale and nonpharmacological multimodal intervention studies for the prevention of dementia have been conducted, although there is as yet no clear evidence of delayed onset of dementia. For instance, the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability is a 2-year multicenter RCT carried out in Finland, testing the effects of a multidomain intervention on delaying cognitive impairment and disability in the elderly at risk [21]. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability enrolled 1260 participants aged 60-77 years who were recruited from previous population-based survey cohorts. The intervention included nutritional guidance, physical exercise, cognitive training and social activities, and management of vascular risk factors. The control group received regular health advice. Effects of the intervention on prevention of dementia have still been investigated in this ongoing RCT. The Alzheimer's Association U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk trial (U.S. POINTER) was initiated in an effort to replicate the results of the Finnish trial in the United States [22]. U.S. POINTER is a 2-year clinical trial to evaluate whether lifestyle interventions that simultaneously target many risk factors protect cognitive function in older adults who are at increased risk for cognitive decline. Although these multimodal interventions can be expected to have strong effects, they are expensive and problematic in terms of social implementation. As a low-cost intervention test, the Maximizing Technology and Methodology for Internet Prevention of Cognitive Decline: the Maintain Your Brain trial targets modifiable risk factors for dementia in general and AD in particular, including physical and cognitive inactivity, depression, overweight and obesity, as well as diabetes, high blood pressure, and smoking [23]. The RCT aims to determine the efficacy of a multimodal targeted Internet intervention on cognitive decline rate in 18,000 nondemented, community-dwelling people aged 55-77 years and on dementia onset delay in the long term. All assessments and interventions are conducted online, which included four basic intervention modules: physical activity, computerized brain training, nutritional advice, and cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Brain training includes a socialization component that starts with making Internet buddies. Advice and helplines are provided regarding smoking cessation, reducing excess consumption of alcohol, and controlling blood pressure and cholesterol. The advantages of this Internet-based intervention are that it is cheap and its social implementation is easy, although the intervention is not applicable for elderly who cannot use the Internet.

The Self-Monitoring Activity Program study is a proof-of-principle trial that aims to determine the effects of a population-based activity program on incident dementia. The program has the potential to provide the first evidence of effectiveness of the self-monitoring tools in incident dementia and may contribute to the development of effective preventative strategies in public health practice to delay dementia onset in older adults. If proven effective in the study, self-monitoring activity will represent a cost-effective and safe method for maintaining a healthy aging.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional sources. Several clinical and experimental studies have investigated the effectiveness of self-monitoring in increasing health status. These relevant articles are appropriately cited.

-

2.

Interpretation: The SMAP study is a single-blind, randomized study that is aimed at evaluating the effects of self-monitoring on dementia incidence in the older adults.

-

3.

Future directions: Although numerous studies have identified the relationships between daily activities and health outcomes included dementia, there is no study which revealed the effectiveness of activity enhancement program on dementia prevention. This trial will identify the therapeutic potential of self-monitoring tools for preventing dementia in primary health care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant numbers: 16dk0110021h0001 and 17le0110004h0001). The funding source had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Nagamatsu L.S., Handy T.C., Hsu C.L., Voss M., Liu-Ambrose T. Resistance training promotes cognitive and functional brain plasticity in seniors with probable mild cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:666–668. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondell S.J., Hammersley-Mather R., Veerman J.L. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:510. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallal P.C., Andersen L.B., Bull F.C., Guthold R., Haskell W., Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franco M.R., Tong A., Howard K., Sherrington C., Ferreira P.H., Pinto R.Z. Older people's perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1268–1276. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bravata D.M., Smith-Spangler C., Sundaram V., Gienger A.L., Lin N., Lewis R. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly M.E., Duff H., Kelly S., McHugh Power J.E., Brennan S., Lawlor B.A. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:259. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li B.Y., Wang Y., Tang H.D., Chen S.D. The role of cognitive activity in cognition protection: from Bedside to Bench. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s40035-017-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada H., Makizako H., Lee S., Doi T., Lee S. Lifestyle activities and the risk of dementia in older Japanese adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:1491–1496. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada H., Doi T., Lee S., Makizako H., Chen L.K., Arai H. Cognitive frailty predicts incident dementia among community-dwelling older people. J Clin Med. 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/jcm7090250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forette F., Seux M.L., Staessen J.A., Thijs L., Birkenhager W.H., Babarskiene M.R. Prevention of dementia in randomised double-blind placebo-controlled Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) trial. Lancet. 1998;352:1347–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organization WH . 1992. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health L, and Welfare of Japan . 2012. Annual Health, Labour, and Welfare Report 2011-2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verghese J., Lipton R.B., Katz M.J., Hall C.B., Derby C.A., Kuslansky G. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morley J.E., Morris J.C., Berg-Weger M., Borson S., Carpenter B.D., Del Campo N. Brain health: the importance of recognizing cognitive impairment: an IAGG consensus conference. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yesavage J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:709–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makizako H., Shimada H., Park H., Doi T., Yoshida D., Uemura K. Evaluation of multidimensional neurocognitive function using a tablet personal computer: Test-retest reliability and validity in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:860–866. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada H., Makizako H., Park H., Doi T., Lee S. Validity of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology-Functional Assessment Tool and Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting the incidence of dementia in older Japanese adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2383–2388. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada H., Makizako H., Doi T., Yoshida D., Tsutsumimoto K., Anan Y. Combined Prevalence of Frailty and Mild Cognitive Impairment in a Population of Elderly Japanese People. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngandu T., Lehtisalo J., Solomon A., Levalahti E., Ahtiluoto S., Antikainen R. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2255–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espeland M.A., Baker L.D., Carrillo M.C., Kivipelto M., Snyder H.M., Su J. Increasing adherence in a center-based trial of lifestyle intervention in older individuals: U.S. pointer trial. Innov Aging. 2018;2:809. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodaty H. Maximising technology and methodology for internet prevention of cognitive decline: the maintain your brain trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1222. [Google Scholar]