Abstract

Background:

There has been a dramatic shift in use of bariatric procedures, but little is known about their long-term comparative effectiveness.

Objective:

To compare weight loss and safety among bariatric procedures.

Design:

Retrospective observational cohort study, January 2005 to September 2015. (ClinicalTrials.gov: )

Setting:

41 health systems in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network.

Participants:

65 093 patients aged 20 to 79 years with body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2 or greater who had bariatric procedures.

Intervention:

32 208 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), 29 693 sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and 3192 adjustable gastric banding (AGB) procedures.

Measurements:

Estimated percent total weight loss (TWL) at 1, 3, and 5 years; 30-day rates of major adverse events.

Results:

Total numbers of eligible patients with weight measures at 1, 3, and 5 years were 44 978 (84%), 20 783 (68%), and 7159 (69%), respectively. Thirty-day rates of major adverse events were 5.0% for RYGB, 2.6% for SG, and 2.9% for AGB. One-year mean TWLs were 31.2% (95% CI, 31.1% to 31.3%) for RYGB, 25.2% (CI, 25.1% to 25.4%) for SG, and 13.7% (CI, 13.3% to 14.0%) for AGB. At 1 year, RYGB patients lost 5.9 (CI, 5.8 to 6.1) percentage points more weight than SG patients and 17.7 (CI, 17.3 to 18.1) percentage points more than AGB patients, and SG patients lost 12.0 (CI, 11.6 to 12.5) percentage points more than AGB patients. Five-year mean TWLs were 25.5% (CI,25.1% to 25.9%) for RYGB, 18.8% (CI, 18.0% to 19.6%) for SG, and 11.7% (CI, 10.2% to 13.1%) for AGB. Patients with diabetes, those with BMI less than 50 kg/m2, those aged 65 years or older, African American patients, and Hispanic patients lost less weight than patients without those characteristics.

Limitation:

Potential unobserved confounding due to nonrandomized design; electronic health record databases had missing outcome data.

Conclusion:

Adults lost more weight with RYGB than with SG or AGB at 1, 3, and 5 years; however, RYGB had the highest 30-day rate of major adverse events. Small subgroup differences in weight loss outcomes were observed.

Primary Funding Source:

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

In the past decade, there has been a dramatic shift in surgical procedures performed for weight loss in the United States (1). Although Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) predominated through the late 2000s, sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has surpassed it in the number of procedures performed in the United States and worldwide (2, 3). The adjustable gastric banding (AGB) procedure was popular in the mid-to-late 2000s, but it now accounts for fewer than 10% of annual U.S. bariatric procedures (4).

Despite this rapid shift, long-term data comparing the efficacy and safety of SG versus RYGB and AGB are lacking. At least 66 randomized controlled trials or observational studies have directly compared RYGB (n = 88 672 total patients) and SG (n = 22 100 total patients) (5–11). However, just 16 involved U.S. samples, and only 5 had at least 5 years of follow-up (n = 845 total SG patients and 867 total RYGB patients) (5–11). Thus, the long-term comparative effectiveness of SG, RYGB, and AGB is largely unknown, and there is no consensus in the medical community about the clinical utility of these procedures for weight loss (12), leading to unwarranted variation in insurance coverage and use of these procedures in the United States (13–16). More data are needed in larger, more broadly representative samples with long-term follow-up to inform clinical and policy decisions about bariatric surgery.

In 2016, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute funded the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) Bariatric Study (PBS) to demonstrate the utility of PCORnet in promoting evidence-based and patient-centered health care. The PBS aims to compare the safety and effectiveness of the most common bariatric procedures in the United States (16, 17) by examining electronic health record data from 11 geographically diverse PCORnet Clinical Data Research Networks (CDRNs) (18).

In this article, we present findings on the comparative effectiveness of SG, RYGB, and AGB for weight loss among adults at 1, 3, and 5 years after surgery. We hypothesized that the procedures would lead to significantly different weight loss trajectories over 5 years. In addition, we leveraged the large sample size enabled by PCORnet to explore the effects of bariatric procedures in clinical subpopulations. These results could help patients, providers, and payers better understand how different bariatric procedures affect health.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

The PBS cohort and protocol were previously described (16). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (lead site) and was approved or determined to be exempt from review by participating sites through individual IRB review or reliance agreements. The PBS is guided by a stakeholder advisory group (comprising patients, advocacy groups, adult and pediatric surgeons, obesity medicine providers, and payers) that helped identify relevant outcomes, prioritize analyses, advise on study design, and plan for dissemination of findings.

We identified patients who had a primary bariatric procedure at health systems affiliated with participating CDRNs (Appendix Table 1, available at Annals.org) from 1 January 2005 through 30 September 2015. PCORnet uses a common data model to facilitate queries of standardized data (18). The PBS team collaborated with the PCORnet Coordinating Center to develop a bariatric case definition and query program. The cohort was identified using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9); Current Procedural Terminology (CPT-4); and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (Appendix Tables 2 and 3, available at Annals.org), which were extracted from the PCORnet common data model at each site.

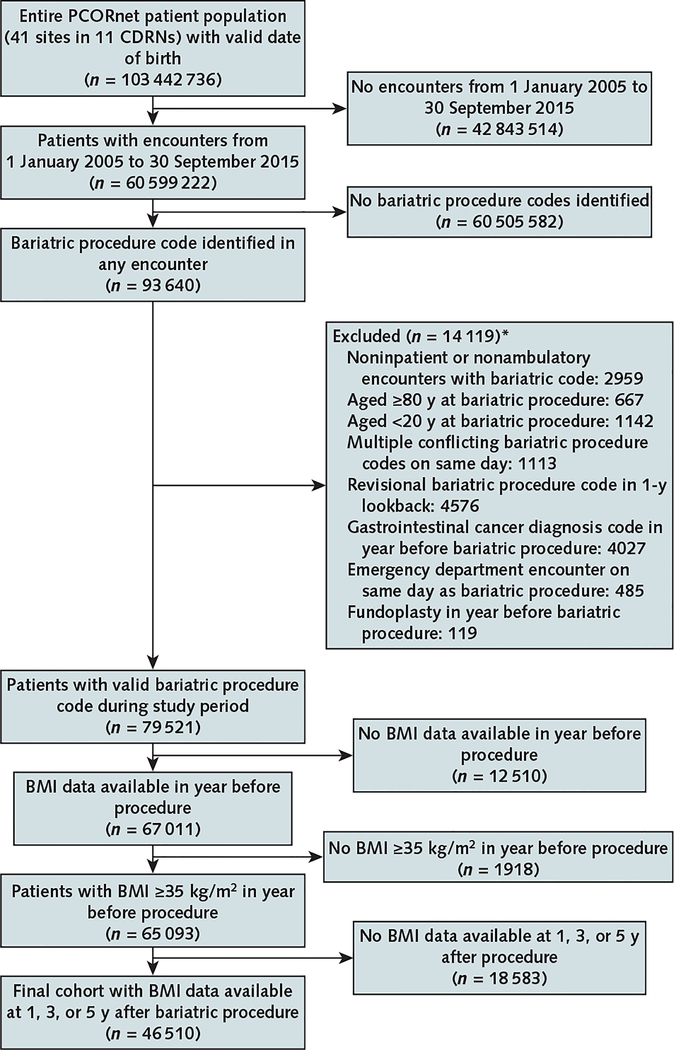

Bariatric procedures were identified from more than 100 million patient records in 41 health systems from the 11 CDRNs. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1. For each patient, the first observed bariatric procedure was considered the index procedure; these had to occur in inpatient or ambulatory care encounters. We then excluded patients who were younger than 20 years or aged 80 years or older at the index procedure (n = 1809); those with multiple conflicting bariatric procedure codes on the same day (n = 1113); those with any revisional bariatric procedure code (n = 4576), gastrointestinal cancer diagnosis code (n = 4027), or fundoplasty (n = 119) in the year before the index procedure; those with an emergency department encounter on the day of the index procedure (n = 485); and those with no body mass index (BMI) data (n = 12 510) or no BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater (n = 1918) in the year before the procedure. We then excluded 18 583 patients who did not have a BMI measurement at 1, 3, or 5 years after surgery, resulting in a final sample of 46 510 adults with baseline and follow-up BMI measurements.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for identification of the adult PCORnet Bariatric Study cohort in 11 CDRNs.

BMI = body mass index; CDRN = Clinical Data Research Network; PCORnet = National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network.

* Patients could be excluded for >1 reason.

Data Extraction

We used SAS queries developed by the PCORnet Coordinating Center to extract information on eligible patients from participating sites, including site identifier; year of surgery; age at the index procedure; sex; race/ethnicity; deidentified dates of all encounters; all measures of height, weight, BMI, and blood pressure; all repeated or revisional bariatric procedures; presence of relevant comorbidities (anxiety, deep venous thrombosis, depression, eating disorder, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, infertility, kidney disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obstructive sleep apnea, lower-extremity osteoarthritis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, psychosis, pulmonary embolism, smoking, or substance use disorder); and all diagnoses and procedures related to pregnancy. We used information from the year before surgery to calculate the Charlson–Elixhauser comorbidity index score for each patient (19). The Charlson–Elixhauser index was developed to predict mortality in older adults, but we used it to help address potential confounding because patients with higher risk for death might be offered a lower-risk procedure. Diagnoses were identified through ICD-9-CM and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine codes (available on request). Additional details on variable construction are provided in the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement (available at Annals.org).

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was percent total weight loss (TWL) at 1, 3, and 5 years, calculated as follows: (weight in kilograms at each time point – weight in kilograms at surgery)/weight in kilograms at surgery × 100 (20). We used pairwise comparisons of percent TWL between procedures (RYGB vs. SG, SG vs. AGB, and RYGB vs. AGB) among patients with at least 1 weight measurement at 1 year (6 to 18 months), 3 years (30 to 42 months), and 5 years (54 to 66 months) after surgery. Follow-up for weight measurements began at the index procedure date and ceased at the end of the study period (30 September 2015) or when the patient switched to a different bariatric procedure. Because pregnancy affects body weight, we ignored anthropometric measurements during pregnancy, defined as the 9 months before and the 3 months after any code indicating full-term delivery, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or abortion. Data were cleaned to remove biologically implausible values for height (<4 or ≥8 ft), weight (<70 or ≥700 lb), and BMI (<15 or ≥90 kg/m2) (21). Secondary analyses examined the proportion of patients achieving TWL greater than 5%, 10%, 20%, and 30% at each time point.

We also examined 30-day rates of major adverse events, defined as any death, reoperation, percutaneous or endoscopic intervention, venous thromboembolism, or failure to be discharged from the hospital within 30 days (22, 23), among 65 093 patients who had complete information at baseline. Longer-term data on adverse events were not available.

Statistical Analysis

Weight Loss Outcomes

Mean adjusted weight at 1, 3, and 5 years with each procedure was estimated using a linear mixed-effects (random-effects) model framework (24). For patients included in each pairwise comparison at each time point, all available postsurgery weight measures were used. Each model estimated a mean population-level time-varying curve for the trend in weight from the time of surgery to the end of the study and included random-effects terms for patient (intercept) and follow-up time (slope). For clinical relevance in presentation, we transformed mean adjusted weight to mean percent TWL and mean weight change, but all inferences were made on the mean weight estimates (including P values) and 95% CIs were transformed from those for mean weight. Additional details are provided in the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement.

Confounding

To control for potential confounding variables, a propensity score model was constructed for each pairwise analysis and time point cohort. The propensity score estimated the probability of having a specific bariatric procedure given baseline (presurgery) covariates. In each cohort, variables were selected and parameters were estimated simultaneously using maximum penalized likelihood estimation and the LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) method (see the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement for details) (25). In addition to adjusting for deciles of predicted propensity score, we included main effects for weight, sex, age, and all other baseline covariates in the outcome model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Adult PBS Cohort*

| Characteristic | AGB | RYGB | SG | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2567 [5.5%]) | (n = 24 982 [53.7%]) | (n = 18 961 [40.8%]) | (n = 46 510 [100.0%]) | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 46.0 (12.3) | 46.0 (11.5) | 44.8 (11.6) | 45.5 (11.6) |

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| 20–44 y | 1194 (46.5) | 11 343 (45.4) | 9538 (50.3) | 22 075 (47.5) |

| 45–64 y | 1198 (46.7) | 12 326 (49.3) | 8518 (44.9) | 22 042 (47.4) |

| 65–80 y | 175 (6.8) | 1313 (5.3) | 905 (4.8) | 2393 (5.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 2046 (79.7) | 20 022 (80.2) | 15247 (80.4) | 37 315 (80.2) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 46.1 (6.7) | 49.6 (8.2) | 48.9 (8.2) | 49.1 (8.2) |

| BMI, n (%) | ||||

| 35–39 kg/m2 | 410 (16.0) | 1904 (7.6) | 1551 (8.2) | 3865 (8.3) |

| 40–49 kg/m2 | 1562 (60.9) | 13 016 (52.1) | 10 545 (55.6) | 25 123 (54.0) |

| 50–59 kg/m2 | 499 (19.4) | 7379 (29.5) | 4992 (26.3) | 12 870 (27.7) |

| ≥60 kg/m2 | 96 (3.7) | 2683 (10.7) | 1873 (9.9) | 4652 (10.0) |

| Mean weight (SD), kg | 121.0 (21.8) | 128.0 (25.8) | 124.8 (25.7) | 126.3 (25.7) |

| Year of surgery, n (%) | ||||

| 2005–2009 | 524 (20.4) | 4207 (16.8) | 452 (2.4) | 5183 (11.1) |

| 2010 | 621 (24.2) | 3939 (15.8) | 1259 (6.6) | 5819 (12.5) |

| 2011 | 654 (25.5) | 5039 (20.2) | 3322 (17.5) | 9015 (19.4) |

| 2012 | 443 (17.3) | 4481 (17.9) | 4053 (21.4) | 8977 (19.3) |

| 2013 | 223 (8.7) | 3731 (14.9) | 4602 (24.3) | 8556 (18.4) |

| 2014 | 94 (3.7) | 3160 (12.7) | 4697 (24.8) | 7951 (17.1) |

| 2015 | 8 (0.3) | 425 (1.7) | 576 (3.0) | 1009 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 286 (11.6) | 4371 (17.8) | 4955 (26.5) | 9612 (21.0) |

| Missing | 90 (3.5) | 398 (1.6) | 254 (1.3) | 742 (1.6) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 10 (0.4) | 194 (0.9) | 218 (1.3) | 422 (1.0) |

| African American | 570 (24.3) | 3415 (15.2) | 4541 (27.9) | 8526 (20.8) |

| Multiple | 32 (1.4) | 281 (1.3) | 152 (0.9) | 465 (1.1) |

| White | 1651 (70.4) | 17 951 (79.9) | 10 769 (66.2) | 30 371 (74.0) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0) | 81 (0.4) | 61 (0.4) | 143 (0.4) |

| Native American | 9 (0.4) | 161 (0.7) | 109 (0.7) | 279 (0.7) |

| Other | 72 (3.1) | 382 (1.7) | 412 (2.5) | 866 (2.1) |

| Missing | 222 (8.7) | 2517 (10.1) | 2699 (14.2) | 5438 (11.7) |

| Mean blood pressure (SD), mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 128.3 (16.1) | 130.7 (17.4) | 130.5 (16.8) | 130.5 (17.1) |

| Diastolic | 77.1 (10.9) | 76.0 (11.3) | 75.0 (11.9) | 75.6 (11.6) |

| Missing blood pressure, n (%) | 188 (7.3) | 1114 (4.5) | 499 (2.6) | 1801 (3.9) |

| Charlson–Elixhauser comorbidity index score, n (%) | ||||

| ≤−1 | 854 (33.3) | 8431 (33.8) | 6203 (32.7) | 15 488 (33.3) |

| 0 | 1387 (54.0) | 12 426 (49.7) | 10 066 (53.1) | 23 879 (51.3) |

| ≥1 | 326 (12.7) | 4125 (16.5) | 2692 (14.2) | 7143 (15.4) |

| Mean days in hospital in year before surgery (SD) | 0.34 (2.4) | 0.42 (4.1) | 0.45 (3.3) | 0.43 (3.7) |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%)† | ||||

| Anxiety | 477 (18.6) | 5494 (22.0) | 3946 (20.8) | 9917 (21.3) |

| Depression | 673 (26.2) | 8346 (33.4) | 5320 (28.1) | 14 339 (30.8) |

| Diabetes | 784 (30.5) | 10 992 (44.0) | 5544 (29.2) | 17 320 (37.2) |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 19 (0.7) | 178 (0.7) | 139 (0.7) | 336 (0.7) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1131 (44.1) | 13 071 (52.3) | 8621 (45.5) | 22 823 (49.1) |

| Eating disorder | 139 (5.4) | 3801 (15.2) | 1043 (5.5) | 4983 (10.7) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 986 (38.4) | 11 381 (45.6) | 6628 (35.0) | 18 995 (40.8) |

| Hypertension | 1499 (58.4) | 15 979 (64.0) | 10 539 (55.6) | 28 017 (60.2) |

| Infertility | 17 (0.7) | 177 (0.7) | 145 (0.8) | 339 (0.7) |

| Kidney disease | 144 (5.6) | 2270 (9.1) | 1410 (7.4) | 3824 (8.2) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 361 (14.1) | 6486 (26.0) | 2799 (14.8) | 9646 (20.7) |

| Lower-extremity osteoarthritis | 52 (2.0) | 436 (1.8) | 326 (1.7) | 814 (1.8) |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 121 (4.7) | 1317 (5.3) | 907 (4.8) | 2345 (5.0) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 25 (1.0) | 318 (1.3) | 204 (1.1) | 547 (1.2) |

| Psychotic disorder | 58 (2.3) | 872 (3.5) | 541 (2.9) | 1471 (3.2) |

| Sleep apnea | 1140 (44.4) | 13 804 (55.3) | 7950 (41.9) | 22 894 (49.2) |

| Smoking | 146 (5.7) | 2346 (9.4) | 1516 (8.0) | 4008 (8.6) |

| Substance use disorder | 27 (1.1) | 523 (2.1) | 434 (2.3) | 984 (2.1) |

AGB = adjustable gastric banding; BMI = body mass index; PBS = National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) Bariatric Study; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG = sleeve gastrectomy.

Baseline was defined as the year before surgery. Adults were defined as patients aged 20–79 y. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, or Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine diagnosis code.

Subgroup Analyses

We examined potential variability in treatment effects across baseline patient characteristics (aged ≥65 or <65 years, sex, race/ethnicity, presence or absence of diabetes, and BMI ≥50 or <50 kg/m2) by including an interaction term between procedure type and each characteristic of interest in the random-effects model framework. Subgroups were chosen on the basis of consensus among study stakeholders, including patients and providers.

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the effects of dropout and missing baseline data on our results, we compared the results of our primary analysis with those from a simple covariate-adjusted model (no propensity scores) run on a single data set that included all longitudinal data among patients with at least 1 postsurgery measurement (n = 56 156) and excluded the race, ethnicity, and blood pressure variables, which were the primary sources of missing baseline data. To address concerns about lack of overlap of the propensity scores, we compared our primary results with those we obtained after trimming the propensity scores for each pairwise analysis and refitting the propensity score and outcome models (further details are provided in the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement). In addition, we examined how the results of each analysis changed if we removed follow-up censoring due to switching to a different procedure. Finally, because the SG technique evolved rapidly during the study period (26, 27), we examined whether 1-year weight loss for SG patients differed by year of surgery.

Role of the Funding Source

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute had no role in the design or conduct of the study or the reporting of the results.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the PBS Cohort

The PBS analytic sample included 46 510 patients (24 982 RYGB patients, 18 961 SG patients, and 2567 AGB patients) (Table 1) with at least 1 weight measurement at 1, 3, or 5 years after surgery. The total numbers of patients with at least 1 BMI measurement at 1, 3, and 5 years were 44 978, 20 783, and 7159, respectively, representing 84%, 68%, and 69% of the 53 351, 30 521, and 10 442 patients who were eligible to be observed at those time points (Table 2 of the Supplement). Five-year follow-up rates differed by procedure, with 86% of SG patients, 67% of RYGB patients, and 55% of AGB patients having a weight measure in this period (Table 2 of the Supplement).

Patients were predominantly white (74%); 21% were African American, and 21% were Hispanic. At baseline, RYGB patients had higher mean BMI (49.6 kg/m2), were more often white (80%), and had greater prevalence of most comorbid conditions than SG or AGB patients. The frequency of procedure types differed across study years, with a sharp decrease in AGB, a sharp increase in SG, and a gradual decrease in RYGB (16).

We compared characteristics of patients in our analytic cohort with those who were excluded due to missing BMI data at baseline and during follow-up (Table 3 of the Supplement). Those without follow-up BMI data were younger (44 vs. 46 years), were less often white (67% vs. 74%), had more recent procedures, and had fewer comorbid conditions. Baseline BMI was more often missing for AGB patients (49%) than RYGB (17%) or SG (9%) patients.

Thirty-Day Rates of Major Adverse Events

Thirty-day rates of major adverse events (Table 4 of the Supplement) were 5.0% for RYGB patients (n = 32 208), 2.6% for SG patients (n = 29 693), and 2.9% for AGB patients (n = 3192). More adverse events were seen with RYGB than with SG (odds ratio [OR], 1.57 [95% CI, 1.40 to 1.77]) or AGB (OR, 1.66 [CI, 1.28 to 2.16]); however, rates did not differ significantly between AGB and SG (OR, 0.99 [CI, 0.72 to 1.36]).

Comparative Effectiveness for Weight Loss

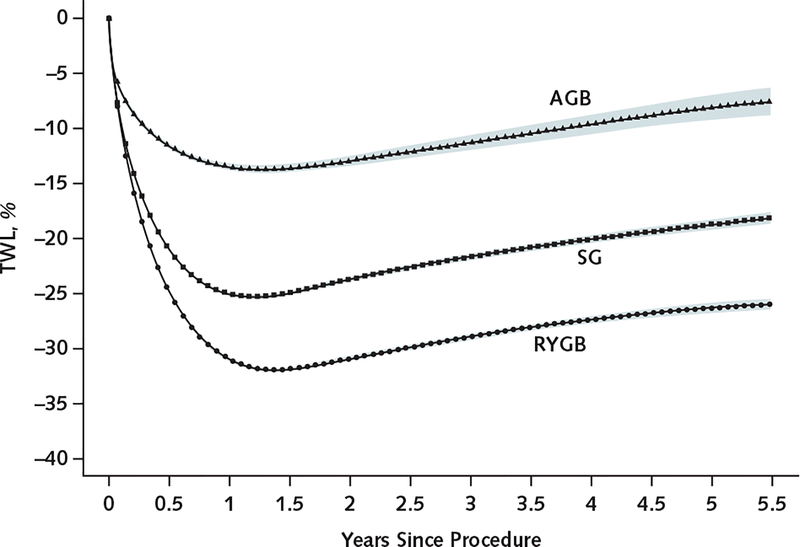

Patients having RYGB had the greatest percent TWL at each time point, and AGB patients had the lowest (Table 2 and Figure 2). At 1 year, average TWL was 31.2% (CI, 31.1% to 31.3%; mean weight loss, 39.6 kg) for RYGB patients, 25.2% (CI, 25.1% to 25.4%; mean weight loss, 32.0 kg) for SG patients, and 13.7% (CI,13.3% to 14.0%; mean weight loss, 17.3 kg) for AGB patients. Patients having RYGB lost 5.9 (CI, 5.8 to 6.1) percentage points (7.6 kg) more of their baseline weight at 1 year than SG patients and 17.7 (CI, 17.3 to 18.1) percentage points (22.5 kg) more than AGB patients. Patients having SG lost 12.0 (CI, 11.6 to 12.5) percentage points (15.3 kg) more of their baseline weight at 1 year than AGB patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative Effectiveness of RYGB, SG, and AGB for TWL Among Adults at 1, 3, and 5 Years*

| Comparison | Time Since Bariatric Procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | ||||

| Patients, n | TWL (95% CI), % | Patients, n | TWL (95% CI), % | Patients, n | TWL (95% CI), % | |

| SG vs. RYGB | ||||||

| SG | 14 929 | −25.2 (−25.4 to −25.1) | 5304 | −21.0 (−21.3 to −20.7) | 1088 | −18.8 (−19.6 to −18.0) |

| RYGB | 19 029 | −31.2 (−31.3 to −31.1) | 9225 | −29.0 (−29.2 to −28.8) | 3676 | −25.5 (−25.9 to −25.1) |

| Difference | − | 5.9 (5.8 to 6.1) | − | 8.0 (7.6 to 8.4) | − | 6.7 (5.8 to 7.7) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| AGB vs. RYGB | ||||||

| AGB | 1681 | −13.7 (−14.0 to −13.3) | 943 | −12.7 (−13.5 to −12.0) | 337 | −11.7 (−13.1 to −10.2) |

| RYGB | 18 684 | −31.4 (−31.5 to −31.3) | 9152 | −29.1 (−29.3 to −28.9) | 3733 | −25.6 (−26.0 to −25.2) |

| Difference | − | 17.7 (17.3 to 18.1) | − | 16.4 (15.6 to 17.2) | − | 13.9 (12.4 to 15.4) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| AGB vs. SG | ||||||

| AGB | 1681 | −13.1 (−13.5 to −12.7) | 933 | −12.0 (−12.8 to −11.2) | 306 | −11.4 (−13.2 to −9.6) |

| SG | 14 664 | −25.1 (−25.3 to −25.0) | 5270 | −20.9 (−21.2 to −20.6) | 1088 | −18.7 (−19.5 to −17.8) |

| Difference | − | 12.0 (11.6 to 12.5) | − | 8.9 (8.0 to 9.8) | − | 7.3 (5.2 to 9.3) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

AGB = adjustable gastric banding; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG = sleeve gastrectomy; TWL = total weight loss.

TWL was calculated as follows: (weight in kilograms at 1, 3, and 5 y – weight in kilograms at baseline)/weight in kilograms at baseline × 100. A propensity score model was constructed for each pairwise analysis and time point. Age at index procedure, sex, race/ethnicity, year of index procedure, baseline body mass index, number of days from baseline weight to bariatric surgery, and baseline Charlson–Elixhauser comorbidity index score were forced into all propensity score models. Site, smoking status, inpatient hospitalizations in the year before surgery, baseline blood pressure, and comorbidities at baseline were included subject to the variable selection process. Further, to account for differing effects of confounders on propensity scores by site, interactions between site and all confounders were made available for selection. In addition to adjustment for deciles of the predicted propensity score, we included main effects for baseline weight, sex, age, and all other baseline covariates listed here in the outcome model. For each pairwise comparison, we restricted the analysis to sites that included ≥1 patient who had each procedure at each time point. See the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement (available at Annals.org) for more details.

Figure 2. Estimated percentage of TWL through 5 y after bariatric surgery, by procedure type.

This plot shows the estimated percentage of TWL for a patient with the average baseline covariate profile using results from our sensitivity analysis, which included all follow-up weight measurements from 56 156 patients with any postsurgery weight observations. Additional details are provided in the Methods section of the text and the Statistical Appendix section of the Supplement. Shaded areas indicate pointwise 95% CIs. AGB = adjustable gastric banding; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG = sleeve gastrectomy; TWL = total weight loss.

At 5 years, patients in each group had, on average, regained some weight. The AGB group regained the least (11.7% TWL at 5 years vs. 13.7% at 1 year; mean weight regained, 2.5 kg), followed by the RYGB (25.5% at 5 years vs. 31.2% at 1 year; mean weight regained, 7.2 kg) and SG (18.8% at 5 years vs. 25.2% at 1 year; mean weight regained, 8.2 kg) groups. Despite these patterns, RYGB patients still had significantly greater TWL after 5 years than SG (difference, 6.7 [CI, 5.8 to 7.7] percentage points; P < 0.001) and AGB (difference, 13.9 [CI, 12.4 to 15.4] percentage points; P < 0.001) patients, and the SG group had significantly greater TWL than the AGB group (difference, 7.3 [CI, 5.2 to 9.3] percentage points; P < 0.001).

Figure 2 illustrates the rapid weight loss with all procedures. After 1.5 years, each group had a slow and steady weight regain through 5.5 years of follow-up.

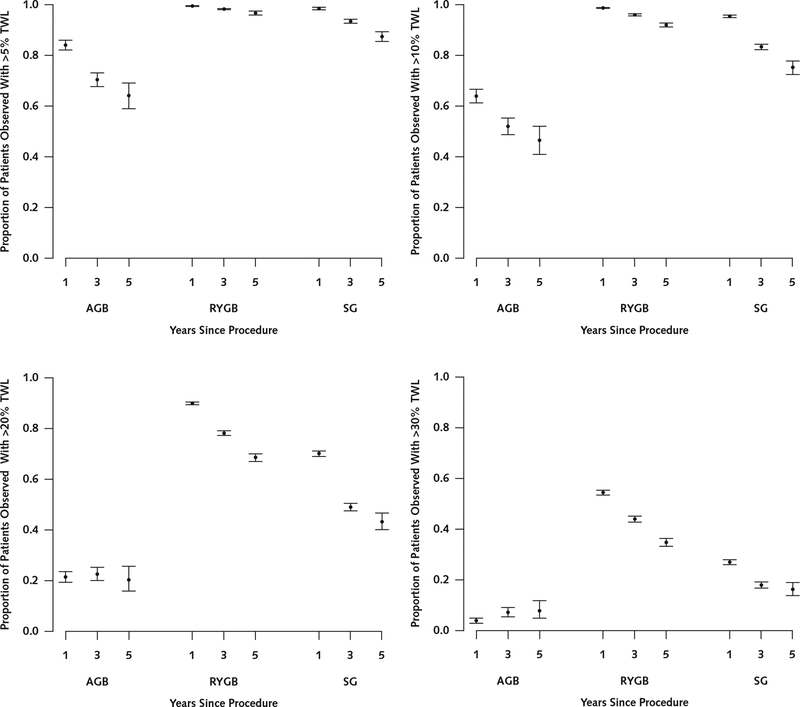

Nearly all patients who had RYGB and SG achieved an estimated TWL greater than 5% at 1, 3, and 5 years (Figure 3). Patients having RYGB were more likely to achieve TWL greater than 10%, 20%, and 30% at all time points. Patients having AGB were less likely to achieve TWL greater than 5%, 10%, 20%, or 30% at all time points compared with RYGB and SG patients.

Figure 3. Proportions of AGB, RYGB, and SG patients with TWL >5%, >10%, >20%, and >30% at 1, 3, and 5 y.

AGB = adjustable gastric banding; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG = sleeve gastrectomy; TWL = total weight loss.

Weight Loss in Patient Subgroups

Patients with diabetes lost less weight than those without diabetes at all time points for all procedures (Table 5 of the Supplement). Patients with a BMI less than 50 kg/m2 at the time of surgery lost less weight than those with a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or greater at all time points for RYGB and SG. This difference was seen at 1 and 3 years in AGB patients, but by 5 years there was no significant difference (Table 6 of the Supplement). Patients aged 65 years or older at the time of surgery lost less weight than younger patients with RYGB and SG at all time points; however, there was no difference by age for AGB at any time point (Table 7 of the Supplement). Men lost less weight with AGB than women at all time points. Men lost more weight with RYGB and SG at 1 year, but there were no differences at 3 and 5 years (Table 8 of the Supplement). African American patients lost less weight with RYGB and SG than white patients at all time points. Hispanic patients lost less weight with RYGB than white patients at all time points. This difference was also seen with SG and AGB at 1 and 3 years, but there were no significant differences at 5 years (Table 9 of the Supplement).

Sensitivity Analyses

Findings did not change when we removed follow-up censoring due to switching to a different bariatric procedure or when we examined whether 1-year weight loss for SG patients differed by year of surgery. Our sensitivity analysis model, which was run on a single data set that included all longitudinal data (n = 56 156), estimated lower TWL for AGB (8.1%), similar TWL for SG (18.7%), and slightly greater TWL for RYGB (26.3%) at 5 years compared with our main model estimates; other estimates were qualitatively similar (Table 10 of the Supplement). Estimates from the trimmed propensity score sensitivity analyses were similar to those from our primary analysis (Table 11 of the Supplement), except that the 5-year comparison between SG and AGB was attenuated and no longer statistically significant, although the number of AGB patients was small (n = 41) and the 95% CI still included our primary analysis estimate.

Comparisons of results by data mart and numbers of patients by site and procedure are provided in Table 1 of the Supplement.

DISCUSSION

In this large multicenter study, we examined the comparative effectiveness of the 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States and demonstrated clear and clinically important differences in weight loss outcomes at 1, 3, and 5 years. Patients who had RYGB lost 5.9 percentage points more weight at 1 year and 6.7 percentage points more at 5 years than SG patients. The proportion of patients achieving 5% weight loss was similar for RYGB and SG, and the proportions losing more than 10% and especially more than 20% or 30% were much larger with RYGB than SG. These findings are compelling because recent smaller studies have suggested little or no difference in short-term weight loss between RYGB and SG (10, 11, 28–33). Other studies have found that RYGB results in greater weight loss than SG at 1 to 4 years of follow-up (5–8, 34–36). Bariatric surgical outcomes can vary widely across surgical centers (37), but the data presented here are probably more broadly representative of the typical experience of patients having bariatric surgery in most major surgical centers in the United States. The magnitude of the weight loss differences we observed will likely be meaningful to patients and providers as they consider treatment options for severe obesity.

When this new information is applied to clinical decision making, the expected magnitude of weight loss with each procedure needs to be tailored to the patient’s specific clinical situation. The large PBS sample enabled subgroup analyses, which aimed to provide data that are relevant for individualized decisions. For example, we found that patients aged 65 years or older, those with diabetes, those with a preoperative BMI less than 50 kg/m2, and racial minority patients generally lost less weight with RYGB and SG than younger, nondiabetic, more severely obese, and non-Hispanic white patients. However, across all of the subgroups we examined, the magnitudes of the differences in TWL were clinically small and generally less than 3%. In contrast, the differences in weight loss between RYGB and SG were larger, and we did not identify any subgroup in which SG outperformed RYGB.

The magnitude of weight loss is not the only factor that patients and providers should consider when discussing bariatric procedure options, and the shared decision-making conversation should include information on risk for adverse events (such as reoperation, death, hypoglycemia, or micronutrient deficiencies) and expected changes in comorbid conditions with each procedure (38). We found that RYGB patients had a higher 30-day rate of major adverse events (5.0%) than SG (2.6%) or AGB (2.9%) patients. To better inform these discussions, future studies should examine longer-term differences in safety outcomes across procedures.

The PBS demonstrates that PCORnet is a valuable new resource for rapidly conducting patient-centered comparative effectiveness research. Its infrastructure enabled standardization of health record data across diverse health systems and analysis of a sufficiently large cohort to identify differences in outcomes across clinically relevant patient subgroups. The engagement of stakeholders throughout the PCORnet research process may also increase the likelihood that the findings are relevant to the decision-making process as patients and providers contemplate the best weight management option (39).

This study has several limitations. First, patients were not randomly assigned, so there was risk for unobserved confounding that may have persisted despite covariate and propensity score adjustment in our pairwise comparisons. Second, a sizable proportion of our cohort was missing BMI data in the electronic health record at baseline or during follow-up, and rates of missingness at baseline and 5 years varied across procedures. This may have introduced bias, although the magnitude and direction of that bias are uncertain. Third, weight data were not systematically collected as part of a prospective data collection effort, as in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (40), so weights at specific time points were model-estimated predictions. Fourth, comorbid conditions were assessed and Charlson–Elixhauser scores were calculated using ICD-9 diagnosis codes, which may underestimate prevalence of comorbidities (such as osteoarthritis), can be inaccurately coded, and do not account for disease severity. Fifth, comparing the effect of bariatric procedures on obesity-related chronic conditions was beyond the scope of this work. Sixth, because this study used deidentified data, we were only able to determine the timing of procedures by year, which prevented us from identifying patients who had missing follow-up data due to administrative censoring. Seventh, we were unable to examine heterogeneity of treatment effects by site because of resource constraints. Finally, the AGB procedure may be underrepresented in this cohort because PCORnet does not include small ambulatory surgical centers.

These analyses demonstrate that RYGB is associated with greater weight loss than SG and that AGB is associated with the least weight loss in a large and geographically and racially diverse population. Health care providers, patients, and policymakers can use these data to inform treatment and insurance coverage decisions. Not every patient with severe obesity will be interested in bariatric surgery (41), but all providers should incorporate a shared decision-making discussion of its potential role into their clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The study team thanks the leaders, project managers, programmers, and staff who were involved in the creation of PCORnet and the 11 CDRNs that provided data to the PBS: Stephen R. Perry, Kin Lam, David Hawkes, Thomas Dundon, and Kelli Kinsman (Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute); Shelly Sital (The Chicago Community Trust); Elizabeth Tarlov and Marian Fitzgibbon (University of Illinois at Chicago); Jasmin Phua (Medical Research Analytics and Informatics Alliance); Mia Gallagher, Lindsey Petro, and Beth Syat (Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School); Prakash Nadkarni and Elizabeth Chris-chilles (University of Iowa); Steffani Roush, Robert Greenlee, and Laurel Verhagen (Marshfield Clinic Research Institute); Umberto Tachinardi (University of Wisconsin); Phillip Reeder, Shiby Antony, and Rania AlShahrouri (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center); James Campbell, Russell Buzalko, and Jay Pedersen (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Dan Connolly (University of Kansas Medical Center); Russell Rothman, David Crenshaw, and Katie Worley (Vanderbilt University Medical Center); Emily Pfaff, Robert Bradford, Kellie Walters, Tim Carey, Timothy Farrell, and D. Wayne Overby (University of North Carolina); Maija Neville-Williams and Rhonda G. Kost (The Rockefeller University); Elizabeth Shenkman, William Hogan, Kathryn McAuliffe, and Gigi Lipori (University of Florida); Rebecca Zuvich Essner (Florida Hospital); Howard Su, Michael George, Michael J. Becich, Barbara Postol, Giselle G. Hamad, Ramesh C. Ramanathan, Bestoun H. Ahmed, William F. Gourash, Bill Shirey, Chuck Borromeo, and Desheng Li (University of Pittsburgh); Anthony T. Petrick, Ilene Ladd, Preston Biegley, and H. Lester Kirchner (Geisinger); Daniel E. Ford, Michael A. Schweitzer, Karl Burke, Harold Lehmann, Megan E. Gauvey-Kern, and Diana Gumas (Johns Hopkins); Rachel Hess, Meghan Lynch, and Reid Holbrook (University of Utah); Jody McCullough, Matt Bolton, Wenke Hwang, Ann Rogers, and Alison Bower (Pennsylvania State University); Cecilia Dobi, Mark Weiner, Anuradha Paranjape, Sharon J. Herring, and Patricia Bernard (Temple University); Janet Zahner, Parth Divekar, Keith Marsolo, and Lisa Boerger (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital); Kimberly J. Holmquist (Kaiser Permanente Southern California); Ray Pablo, Roni Bracha, and Robynn Zender (University of California, Irvine); Lucila Ohno-Machado, Paulina Paul, and Michele Day (University of California, San Diego); Thomas Carton, Elizabeth Crull, and Iben McCormick-Ricket (Louisiana Public Health Institute); Ashley Vernon, Malcolm Robinson, Scott Shikora, David Spector, Eric Sheu, Edward Mun, Matthew Hutter, Shawn Murphy, Jeffrey Klann, and Denise Gee (Partners Healthcare); Daniel Jones, Benjamin Schneider, Griffin Weber, and Robert Andrews (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center); Donald Hess, Brian Carmine, Miguel Burch, and Galina Lozinski (Boston Medical Center); Ken Mandl, Jessica Lyons, and Margaret Vella (Harvard Medical School); and Joseph Skelton and Kun Wei (Wake Forest Integrated Health System).

Financial Support: This study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute via contract OBS-1505–30683.

Disclosures: Dr. Arterburn reports grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. Dr. Courcoulas reports grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Allurion, and Covidien/Ethicon outside the submitted work. Dr. Xanthakos reports grants from TARGET PharmaSolutions and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases outside the submitted work. Dr. Inge reports honoraria from and stock options in Standard Bariatrics outside the submitted work. Dr. Tavakkoli reports personal fees from Medtronic and AMAG Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Dr. Nirav Desai reports employment with Shire. Dr. Hynes reports a Research Career Scientist Award from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs during the conduct of the study. Dr. Apovian reports personal fees from Nutrisystem, Zafgen, Sanofi-Aventis, Orexigen, Novo Nordisk, GI Dynamics, Takeda, Scientific Intake, Xeno Biosciences, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, EnteroMedics, and Bariatrix Nutrition outside the submitted work; grants from Orexigen, Aspire Bariatrics, GI Dynamics, Myos, Takeda, the Vela Foundation, the Dr. Robert C. and Veronica Atkins Foundation, Coherence Lab, Energesis, and the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work; and past ownership of stock in Science-Smart LLC. Mr. Nadglowski reports employment with the Obesity Action Coalition, which receives grants and other support from bariatric surgery–related companies, including Ethicon, Medtronic, and many bariatric surgery vitamin supplementation companies. Ms. Saizan reports a grant from the Louisiana Public Health Institute during the conduct of the study. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms .do?msNum=M17–2786.

APPENDIX: PCORNET BARIATRIC STUDY

COLLABORATIVE

The PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative includes the following key investigators and stakeholders who made substantial contributions to the manuscript as authors: Joseph Vitello, MD (Jesse Brown VA Medical Center); Elisha Malanga, BS (COPD Foundation); Corrigan L. McBride, MD, and James McClay, MD, MS (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Emily Harmata, MSN, and David Schlundt, PhD (Vanderbilt University); Tammy St. Clair, LMSW; Joe Nadglowski, BS (Obesity Action Coalition); Anita P. Courcoulas, MD, MPH, and Kathleen M. McTigue, MD, MS, MPH (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center); Marc Michalsky, MD (Nationwide Children’s Hospital); Nirav Desai, MD (Boston Children’s Hospital); Alberto Odor, MD (University of California, Davis); Rosalinde Saizan, RN, and William Richardson, MD (Ochsner Surgical Weight Loss Center); Caroline Apovian, MD, and William G. Adams, MD (Boston Medical Center/Boston University School of Medicine); Elizabeth Cirelli, MSN, RN (Brigham and Women’s Hospital); Roni Zeiger, MD (Smart Patients, Inc.); Laura Rasmussen-Torvik, PhD (Northwestern Medicine); Jessica Sturtevant, MS, Casie E. Horgan, MPH, Gabrielle Purcell, MPH, Sengwee Toh, ScD, Jeffrey Brown, PhD, and Ali Tavakkoli, MD (Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute); John H. Holmes, PhD (University of Pennsylvania); Rabih Nemr, MD (Lutheran Medical Center); Ana Emiliano, MD, and Jonathan N. Tobin, PhD (Rockefeller University); Jeanne Clark, PhD, and Wendy Bennett, MD, MPH (Johns Hopkins University); Thomas H. Inge, MD, PhD (University of Colorado, Denver, and Children’s Hospital of Colorado); Stavra A. Xanthakos, MD (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center); Lydia Bazzano, MD, PhD (Tulane University School of Public Health); Elizabeth Nauman, MPH, PhD (Louisiana Public Health Research Institute); Denise M. Hynes, PhD, MPH, RN (University of Illinois); David Meltzer, MD, PhD (University of Chicago); Bipan Chand, MD (Loyola Medicine); Jeffrey J. VanWormer, PhD (Marshfield Clinic Research Institute); Lemuel Russell Waitman, PhD (Kansas University Medical Center); Lindsay G. Cowell, PhD (University of Texas Southwestern); Lawrence P. Hanrahan, PhD, MS (University of Wisconsin–Madison); Meredith Duke, MBA, MD (University of North Carolina); Daniel M. Herron, MD (Mount Sinai Health System); Sameer Malhotra, MD, MA (Weill Cornell Medical College); Jenny Choi, MD (Montefiore Medical Center); Jiang Bian, PhD (University of Florida Health); Michelle R. Lent, PhD (Geisinger Health); Jennifer L. Kraschnewski, MD, MPH, and Julie Tice, MS (Pennsylvania State University); Michael A. Edwards, MD (Temple University); Molly Conroy, MD, MPH (University of Utah); Matthew F. Daley, MD (Kaiser Permanente Colorado); Michael Horberg, MD (Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic); Jay R. Desai, PhD, MPH (Health Partners); Stephanie L. Fitzpatrick, PhD (Kaiser Permanente Northwest); Douglas S. Bell, MD, PhD (University of California, Los Angeles); Erin Roe, MD (Baylor Scott & White); Xiaobo Zhou, MD (Wake Forest School of Medicine); Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center); David E. Arterburn, MD, MPH, Robert D. Wellman, MS,R. Yates Coley, PhD, Jane Anau, BS, Roy Pardee, JD, MA, and Andrea Cook, PhD (Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute); Steven R. Smith, MD (Florida Hospital); Andrew O. Odegaard, MPH, PhD (University of California, Irvine); Cheri D. Janning, RN, BSN, MS (Duke Clinical & Translational Science Institute); Neely A. Williams, MDiv (Community Partners’ Network); Karen J. Coleman, PhD; and Sameer Murali, MD (Kaiser Permanente Southern California).

Appendix Table 1.

Participating PCORnet CDRNs and Sites Contributing Data

| CDRN | Sites Contributing Data |

|---|---|

| Chicago Area Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Network (CAPriCORN) | Loyola Medicine |

| Northwestern Medicine | |

| University of Chicago Medical Center | |

| University of Illinois Hospital & Health Science System | |

| Greater Plains Collaborative (GPC) | Marshfield Clinic |

| University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center | |

| University of Iowa Healthcare | |

| University of Kansas Medical Center | |

| University of Wisconsin – Madison | |

| Kaiser Permanente & Strategic Partners Patient Outcomes Research To Advance Learning (PORTAL) | Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (formerly Group Health Research Institute) |

| HealthPartners Research Foundation | |

| Kaiser Permanente Colorado | |

| Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic States | |

| Kaiser Permanente Northwest | |

| Kaiser Permanente Southern California | |

| Mid-South | Greenway |

| University of North Carolina | |

| Vanderbilt University Medical Center | |

| New York City Clinical Data Research Network (NYC-CDRN) | Mount Sinai |

| New York University | |

| Weill Cornell | |

| Montefiore/Einstein | |

| OneFlorida Clinical Research Consortium | University of Florida Health |

| Orlando Health | |

| Tallahassee Memorial Health System | |

| PaTH Towards a Learning Health System Clinical Data Research Network (PaTH) | Geisinger Health System |

| Johns Hopkins University and Health System* | |

| Penn State College of Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center | |

| Temple Health System, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University | |

| University of Pittsburgh and UPMC | |

| UPMC Health Plan* | |

| University of Utah and University of Utah Health Care | |

| A Pediatric Learning Health System (PEDSnet) | Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center |

| Nemours | |

| Nationwide Children’s Hospital | |

| Patient-Centered SCAlable National Network for Effectiveness Research (pSCANNER) | University of California, Irvine |

| University of California, Los Angeles | |

| Research Action for Health Network (REACHnet) | Baylor Scott & White Health |

| Ochsner Health System | |

| Tulane University | |

| Scalable Collaborative Infrastructure for a Learning Healthcare System (SCILHS) | Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center |

| Boston HealthNet* | |

| Partners Health | |

| Wake Forest Baptist Hospital | |

CDRN = Clinical Data Research Network; PCORnet = National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network; UPMC = University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Johns Hopkins University and Health System, UPMC Health Plan, and Boston HealthNet did not contribute data for this article but will for future analyses.

Appendix Table 2.

Bariatric Surgery Procedure Codes Used as Inclusion Criteria*

| Description | Code | Code | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Assignment | ||

| Gastric restrictive procedure, without gastric bypass, for morbid obesity; other than vertical-banded gastroplasty | 43843 | CPT-4 | AGB |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with short limb (150 cm or less) Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy | 43846 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

| Laparoscopy, surgical; gastric restrictive procedure, adjustable gastric band includes placement of subcutaneous port | S2082 | HCPCS | AGB |

| Gastrectomy, partial, distal; with Roux-en-Y reconstruction | 43633 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; placement of adjustable gastric restrictive device (e.g., gastric band and subcutaneous port components) | 43770 | CPT-4 | AGB |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; with gastric bypass and small intestine reconstruction to limit absorption | 43645 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

| Laparoscopy, gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity, with short limb (less than 100 cm) Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy | S2085 | HCPCS | RYGB |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; longitudinal gastrectomy (i.e., sleeve gastrectomy) | 43775 | CPT-4 | SG |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; with gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy (Roux limb 150 cm or less) | 43644 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with small intestine reconstruction to limit absorption | 43847 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

| High gastric bypass | 44.31 | ICD-9 | RYGB |

| Laparoscopic vertical (sleeve) gastrectomy | 43.82 | ICD-9 | SG |

| Laparoscopic gastric restrictive procedure | 44.95 | ICD-9 | AGB |

| Open and other partial gastrectomy | 43.89 | ICD-9 | SG |

| Laparoscopic gastroenterostomy | 44.38 | ICD-9 | RYGB |

| Other gastroenterostomy without gastrectomy | 44.39 | ICD-9 | RYGB |

| Laparoscopic gastric restrictive procedure with gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy | 43844 | CPT-4 | RYGB |

AGB = adjustable gastric banding; CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; PCORnet = National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network; RYGB = Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG = sleeve gastrectomy.

Patients who had one of these procedure codes during the study period were considered to be potentially eligible for the PCORnet Bariatric Study. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria and codes are provided in the text and Appendix Table 3.

Appendix Table 3.

Codes Used as Exclusion Criteria*

| Description | Code | Code Type |

|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; removal of adjustable gastric restrictive device component only | 43772 | CPT-4 |

| Revision of gastrojejunal anastomosis (gastrojejunostomy) with reconstruction, with or without partial gastrectomy or intestine resection; with vagotomy | 43865 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, without gastric bypass, for morbid obesity; vertical-banded gastroplasty | 43842 | CPT-4 |

| Revision of gastroduodenal anastomosis (gastroduodenostomy) with reconstruction; without vagotomy | 43850 | CPT-4 |

| Revision of gastroduodenal anastomosis (gastroduodenostomy) with reconstruction; with vagotomy | 43855 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; revision of adjustable gastric restrictive device component only | 43771 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; removal and replacement of adjustable gastric restrictive device component only | 43773 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure with partial gastrectomy, pylorus-preserving duodenoileostomy and ileoileostomy (50 to 100 cm common channel) to limit absorption (biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) | 43845 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, open; removal of subcutaneous port component only | 43887 | CPT-4 |

| Revision of gastrojejunal anastomosis (gastrojejunostomy) with reconstruction, with or without partial gastrectomy or intestine resection; without vagotomy | 43860 | CPT-4 |

| Revision, open, of gastric restrictive procedure for morbid obesity, other than adjustable gastric restrictive device (separate procedure) | 43848 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, open; revision of subcutaneous port component only | 43886 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; removal of adjustable gastric restrictive device and subcutaneous port components | 43774 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, open; removal and replacement of subcutaneous port component only | 43888 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopic gastroplasty | 44.68 | ICD-9 |

| Laparoscopic removal of gastric restrictive device(s) | 44.97 | ICD-9 |

| Laparoscopic revision of gastric restrictive procedure | 44.96 | ICD-9 |

| Gastrectomy, total; with Roux-en-Y reconstruction | 43621 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, partial, proximal, thoracic or abdominal approach including esophagogastrostomy, with vagotomy; with pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy | 43639 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, partial, distal; with formation of intestinal pouch | 43634 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, partial, distal; with gastrojejunostomy | 43632 | CPT-4 |

| Gastric restrictive procedure, without gastric bypass, for morbid obesity; vertical-banded gastroplasty | 43842 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, partial, proximal, thoracic or abdominal approach including esophagogastrostomy, with vagotomy; | 43638 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, partial, distal; with gastroduodenostomy | 43631 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, total; with esophagoenterostomy | 43620 | CPT-4 |

| Gastrectomy, total; with formation of intestinal pouch, any type | 43622 | CPT-4 |

| Gastroenterostomy without gastrectomy | 44.3 | ICD-9 |

| Partial gastrectomy with anastomosis to esophagus | 43.5 | ICD-9 |

| Other partial gastrectomy | 43.8 | ICD-9 |

| Total gastrectomy | 43.9 | ICD-9 |

| Partial gastrectomy with anastomosis to duodenum | 43.6 | ICD-9 |

| Other total gastrectomy | 43.99 | ICD-9 |

| Partial gastrectomy with anastomosis to jejunum | 43.7 | ICD-9 |

| Total gastrectomy with intestinal interposition | 43.91 | ICD-9 |

| Partial gastrectomy with jejunal transposition | 43.81 | ICD-9 |

| Laparoscopic procedures for creation of esophagogastric sphincteric competence | 44.67 | ICD-9 |

| Esophagogastroplasty | 44.65 | ICD-9 |

| Other procedures for creation of esophagogastric sphincteric competence | 44.66 | ICD-9 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, esophagomyotomy (Heller type), with fundoplasty, when performed | 43279 | CPT-4 |

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via laparotomy, except neonatal; without | 43332 | CPT-4 |

| implantation of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Laparoscopy, surgical, repair of paraesophageal hernia, includes fundoplasty, when performed; without | 43281 | CPT-4 |

| implantation of mesh | ||

| Laparoscopy, surgical, esophagogastric fundoplasty (e.g., Nissen, Toupet procedures) | 43280 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, esophageal lengthening procedure (e.g., Collis gastroplasty or wedge gastroplasty) (List | 43283 | CPT-4 |

| separately in addition to code for primary procedure) | ||

| Esophageal lengthening procedure (e.g., Collis gastroplasty or wedge gastroplasty) (List separately in addition to | 43338 | CPT-4 |

| code for primary procedure) | ||

| Esophagogastric fundoplasty partial or complete; laparotomy | 43327 | CPT-4 |

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via thoracotomy, except neonatal; without | 43334 | CPT-4 |

| implantation of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via laparotomy, except neonatal; with implantation | 43333 | CPT-4 |

| of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Esophagogastric fundoplasty (e.g., Nissen, Belsey IV, Hill procedures) | 43324 | CPT-4 |

| Esophagogastric fundoplasty; with gastroplasty (e.g., Collis) | 43326 | CPT-4 |

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via thoracotomy, except neonatal; with | 43335 | CPT-4 |

| implantation of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Esophagogastric fundoplasty; with fundic patch (Thal-Nissen procedure) | 43325 | CPT-4 |

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via thoracoabdominal incision, except neonatal; | 43336 | CPT-4 |

| without implantation of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Repair, paraesophageal hiatal hernia (including fundoplication), via thoracoabdominal incision, except neonatal; | 43337 | CPT-4 |

| with implantation of mesh or other prosthesis | ||

| Esophagogastric fundoplasty partial or complete; thoracotomy | 43328 | CPT-4 |

| Laparoscopy, surgical, repair of paraesophageal hernia, includes fundoplasty, when performed; with implantation of mesh | 43282 | CPT-4 |

CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

Patients who had any of these codes identified in the year before their first observed primary bariatric procedure were excluded.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: See the Supplement. Additional details are available from Dr. Arterburn (arterburn.d@ghc.org). Statistical code: Available from Dr. Arterburn. Data set: Our data access committee will review any requests for access to data and make a determination. Please e-mail Dr. Arterburn for details on making a request.

From Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, Washington (D.A., R.W., R.Y.C., J.A., R.P., A.C.); Rockefeller University, New York, New York (A.E.); The Translational Research Institute for Metabolism and Diabetes, Florida Hospital, Orlando, Florida (S.R.S.); University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine, Irvine, California (A.O.O.); Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, California (S.M., K.J.C.); Community Partners’ Network, Nashville, Tennessee (N.W.); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (A.C., K.M.M.); Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (S.T., J.S., C.H.); and Duke Clinical & Translational Science Institute, Durham, North Carolina (C.J.).

Contributor Information

David Arterburn, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98108..

Robert Wellman, Community Partners’ Network, 850 West Trinity Lane, Nashville, TN 37207..

Ana Emiliano, Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics and Metabolism, Rockefeller University, Hospital 431, Box 179, 1200 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065..

Steven R. Smith, The Translational Research Institute for Metabolism and Diabetes, Florida Hospital, 301 East Princeton Street, Orlando, FL 32804..

Andrew O. Odegaard, Department of Epidemiology, School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, 224 Irvine Hall, Irvine, CA 92697..

Sameer Murali, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, 17296 Slover Avenue, Fontana, CA 92337..

Neely Williams, Community Partners’ Network, 850 West Trinity Lane, Nashville, TN 37207..

Karen J. Coleman, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, 100 South Los Robles, 4th Floor, Pasadena, CA 91101..

Anita Courcoulas, Department of Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, 3800 Boulevard of the Allies, Suite 390, Pittsburgh, PA 15213..

R. Yates Coley, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98108..

Jane Anau, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98108..

Roy Pardee, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98108..

Sengwee Toh, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 401 Park Drive, Suite 401, Boston, MA 02215..

Cheri Janning, Duke Clinical & Translational Science Institute, 701 West Trinity Avenue, #111, Durham, NC 27701..

Andrea Cook, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Avenue, Suite 1600, Seattle, WA 98108..

Jessica Sturtevant, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 401 Park Drive, Suite 401, Boston, MA 02215..

Casie Horgan, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 401 Park Drive, Suite 401, Boston, MA 02215..

Kathleen M. McTigue, Center for Research on Health Care, University of Pittsburgh, 230 McKee Place, Suite 600, Pittsburgh, PA 15213..

References

- 1.Arterburn DE, Courcoulas AP. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic conditions in adults. BMJ. 2014;349:g3961 [PMID: 25164369] doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25: 1822–32. [PMID: 25835983] doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Zundel N, Buchwald H, et al. Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO worldwide survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2279–89. [PMID: 28405878] doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2666-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponce J, DeMaria EJ, Nguyen NT, Hutter M, Sudan R, Morton JM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of bariatric surgery procedures in 2015 and surgeon workforce in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1637–9. [PMID: 27692915] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Lai D, Wu D. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy to treat morbid obesity-related comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:429–42. [PMID: 26661105] doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1996-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, et al. ; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:641–51. [PMID: 28199805] doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, Smith VA, Yancy WS Jr, Weidenbacher HJ, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1046–55. [PMID: 27579793] doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudan R, Maciejewski ML, Wilk AR, Nguyen NT, Ponce J, Morton JM. Comparative effectiveness of primary bariatric operations in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:826–34. [PMID: 28236529] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman KJ, Huang YC, Hendee F, Watson HL, Casillas RA, Brookey J. Three-year weight outcomes from a bariatric surgery registry in a large integrated healthcare system. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:396–403. [PMID: 24951065] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kröll D, Borbély Y, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255–65. [PMID: 29340679] doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, Juuti A, Leivonen M, Peromaa-Haavisto P, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241–54. [PMID: 29340676] doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808–17. [PMID: 28586904] doi: 10.7326/M17-0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reames BN, Finks JF, Bacal D, Carlin AM, Dimick JB. Changes in bariatric surgery procedure use in Michigan, 2006–2013. JAMA. 2014;312:959–61. [PMID: 25182106] doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reames BN, Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Goodney PR, Dzebisashvili N, Goodman DC, et al. Variation in the Care of Surgical Conditions: Obesity. A Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Series. Lebanon, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macht R, Rosen A, Horn G, Carmine B, Hess D. An exploration of system-level factors and the geographic variation in bariatric surgery utilization. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1635–8. [PMID: 27034061] doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2164-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toh S, Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Harmata EE, Pardee R, Saizan R, Malanga E, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) Bariatric Study cohort: rationale, methods, and baseline characteristics. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6:e222 [PMID: 29208590] doi: 10.2196/resprot.8323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inge TH, Coley RY, Bazzano LA, Xanthakos SA, McTigue K, Arterburn D, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative. Comparative effectiveness of bariatric procedures among adolescents: the PCORnet Bariatric Study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018. [PMID: 29793877] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleurence RL, Curtis LH, Califf RM, Platt R, Selby JV, Brown JS. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:578–82. [PMID: 24821743] doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:749–59. [PMID: 21208778] doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brethauer SA, Kim J, el Chaar M, Papasavas P, Eisenberg D, Rogers A, et al. ; ASMBS Clinical Issues Committee. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:489–506. [PMID: 26093765] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arterburn DE, Alexander GL, Calvi J, Coleman LA, Gillman MW, Novotny R, et al. Body mass index measurement and obesity prevalence in ten U.S. health plans. Clin Med Res. 2010;8:126–30. [PMID: 20682758] doi: 10.3121/cmr.2010.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, et al. ; Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:445–54. [PMID: 19641201] doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arterburn D, Powers JD, Toh S, Polsky S, Butler MG, Portz JD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding vs laparoscopic gastric bypass. JAMA Surg. 2014;149: 1279–87. [PMID: 25353723] doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–74. [PMID: 7168798] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibshirani R The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Stat Med. 1997;16:385–95. [PMID: 9044528] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balla A, Quaresima S, Leonetti F, Paone E, Brunori M, Messina T, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy changes in the last decade: differences in morbidity and weight loss. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:1165–71. [PMID: 28430045] doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrer-Márquez M, García-Díaz JJ, Moreno-Serrano A, García-Díez JM, Ferrer-Ayza M, Alarcón-Rodríguez R, et al. Changes in gastric volume and their implications for weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;27:303–9. [PMID: 27484976] doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2274-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barzin M, Khalaj A, Motamedi MA, Shapoori P, Azizi F, Hosseinpanah F. Safety and effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy versus gastric bypass: one-year results of Tehran Obesity Treatment Study (TOTS). Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:S62–9. [PMID: 28224030] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149: 275–87. [PMID: 24352617] doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kehagias I, Karamanakos SN, Argentou M, Kalfarentzos F. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the management of patients with BMI <50 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1650–6. [PMID: 21818647] doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0479-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helmiö M, Victorzon M, Ovaska J, Leivonen M, Juuti A, Peromaa-Haavisto P, et al. Comparison of short-term outcome of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a prospective randomized controlled multicenter SLEEVE-PASS study with 6-month follow-up. Scand J Surg. 2014;103:175–81. [PMID: 24522349] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osland E, Yunus RM, Khan S, Memon B, Memon MA. Weight loss outcomes in laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (LVSG) versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) procedures: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27:8–18. [PMID: 28145963] doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yip S, Plank LD, Murphy R. Gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1994–2003. [PMID: 23955521] doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1030-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Chaar M, Hammoud N, Ezeji G, Claros L, Miletics M, Stoltzfus J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single center experience with 2 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2015;25:254–62. [PMID: 25085223] doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1388-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Zhao H, Cao Z, Sun X, Zhang C, Cai W, et al. A randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of morbid obesity in China: a 5-year outcome. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1617–24. [PMID: 24827405] doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1258-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, Ko CY, Cohen ME, Merkow RP, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254:410–20. [PMID: 21865942] doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c9dac [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibrahim AM, Ghaferi AA, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Variation in outcomes at bariatric surgery centers of excellence. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:629–36. [PMID: 28445566] doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstein AL, Marascalchi BJ, Spiegel MA, Saunders JK, Fagerlin A, Parikh M. Patient preferences and bariatric surgery procedure selection; the need for shared decision-making. Obes Surg. 2014; 24:1933–9. [PMID: 24788395] doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1270-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–4. [PMID: 25167382] doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, O’Rourke RW, Dakin G, Patchen Dellinger E, Flum DR, et al. Preoperative factors and 3-year weight change in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) consortium. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:1109–18. [PMID: 25824474] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arterburn D, Flum DR, Westbrook EO, Fuller S, Shea M, Bock SN, et al. ; CROSSROADS Study Team. A population-based, shared decision-making approach to recruit for a randomized trial of bariatric surgery versus lifestyle for type 2 diabetes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:837–44. [PMID: 23911345] doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.