Abstract

Background:

Although takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) typically affects the apical and/or midventricular segments, several recent cases have reported a reverse or inverted variant of TTC. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic findings in patients presenting as inverted TTC and compare those parameters to those presenting as mid or apical variant.

Hypothesis:

The clinical features of inverted TTC are different from those of other types of TTC.

Methods:

Of 103 patients enrolled from the TTC registry database, 20 showed inverted TTC (inverted TTC group), and 83 showed mid or apical variant (other TTC group).

Results:

Clinical presentations and in‐hospital courses were mostly similar between the groups. However, the inverted TTC group was younger (median, 54.5 vs 64.0 years; P = 0.006) than other TTC and had a higher prevalence of triggering stress (100% vs 77%, P = 0.018), whereas other TTC group had higher prevalence of dyspnea (58% vs 30%, P = 0.025), pulmonary edema (46% vs 20%, P = 0.035), cardiogenic shock (36% vs 10%, P = 0.023), T‐wave inversion (81% vs 60%, P = 0.049), and significant reversible mitral regurgitation (MR) (19% vs 0%, P = 0.033). Also, the inverted TTC group had significantly higher creatine kinase MB fraction (CK‐MB); CK‐MB (median, 30.7 vs 7.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001) and troponin‐I (median, 13.1 vs 1.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001), but lower N‐terminalpro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) levels (median, 613.3 vs 4987.0 pg/mL; P = 0.020).

Conclusions:

Inverted TTC presents at a younger age and has a higher prevalence of triggering stress, whereas other TTC has a higher prevalence of heart failure symptoms, significant reversible MR, and T‐wave inversion and higher NT‐proBNP levels despite other clinical features that are mostly similar. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

This study was supported by the Samsung Changwon Hospital Hyoseok Research Fund. The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC), also known as transient left ventricular (LV) ballooning syndrome, stress‐induced cardiomyopathy, is characterized by transients LV dysfunction in the apical and/or midventricular segments, in the absence of significant angiographic coronary stenoses, provoked by an episode of emotional or physical stress.1, 2, 3, 4 Since the original description of this syndrome showing apical ballooning with the appearance of a Japanese octopus trap or Tako‐tsubo in Japanese, the reverse or inverted patternas a novel variant of this entity has been recently recognized involving basal and midventricular segments and preserved contractility of apical segments.5, 6, 7, 8 However, there are few data regarding the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and echocardiographic findings of this novel variant. Moreover, a limited amount of literature exists about clinical characteristics and in‐hospital courses of illness of reverse or inverted TTC.9, 10 In this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic findings of patients with inverted TTC and compared those parameters with those of a mid or apical variant of TTC.

Methods

Study Subjects

We approached 103 consecutive patients enrolled in the TTC registry database at the Samsung Changwon Hospital and Samsung Medical Center from January 2004 to December 2009. From 5078 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of an acute coronary syndrome, including ST‐ and non–ST‐elevation myocardial infarction, who had an urgent coronary angiography (CAG), 103 (2%) patients were diagnosed with TTC. The enrolled 103 patients with TTC were divided into 2 groups: 20 patients were grouped into the reverse or inverted TTC, and 83 were grouped into the other TTC group, including classic or takotsubo type (n = 79), and midventricular type (n = 4). The criteria for inclusionwere as follows: (1) transient akinesia/dyskinesia beyond a single major coronary artery vascular distribution, (2) absence of significant coronary artery disease on coronary angiograms (diameter stenosis <50% by visual estimation) or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture, and (3) new electrocardiographic (ECG) changes (ST‐segment changes, T‐wave inversion, or Qwave).9 Hypertension was defined as repeated measurements of ≥140 mmHg systolic blood pressure or ≥90 mmHg diastolic blood pressure, or previous antihypertensive drug treatment. Diabetes mellitus was defined as serum glucose level of 125 mg/dL or higher, a history of diabetes mellitus, or current use of antidiabetic therapy. Current smoking was defined as having smoked cigarettes <1 year before patients presented with TTC. Cardiogenic shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg for ≥30 minutes that was not responsive to fluid administration alone, accompanied by evidence of tissue hypoperfusion in the setting of clinically adequate or elevated LV filling pressures.11 Pulmonary edema was defined as the presence of rales at pulmonary examination or a radiographic report of pulmonary alveolar/interstitial congestion at initial chest roentgenogram.11 The protocol was approved by the institutional research ethics committee. The recommendations of the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki were met.

The medical history and coronary risk factors were obtained from medical records combined with a patient questionnaire. Any physical or emotional stresses prior to the onset of this syndrome were specifically investigated. ECG and laboratory data, including cardiac enzymes (creatine kinase [CK], creatine kinase MB fraction [CK‐MB], and troponin‐I), were recorded during the acute phase and were followed until the abnormalities disappeared.

All patients under went coronary angiography concomitant with LV angiography at the time of presentation. To exclude vasospastic angina, a spasm provocation test was performed in 74 (72%) patients by intracoronary ergonovine infusion as described previously.12

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiographic examinations were performed in all patients with a 2.5 MHz transducer attached to a commercially available Doppler echocardiography machine, on the first hospital day or within 24 hours of CAG and follow‐up. LV end‐diastolic and end‐systolic diameters, along with septal and posterior wall thickness at enddiastole were measured in the parasternal long axis view, using 2‐dimensional (2D)–guided M‐mode echocardiography according to the recommendations of chamber quantification.13 The LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated by the modified Simpson method. The valvular regurgitation (VR) was assessed by color Doppler flow mapping of spatial distribution of the regurgitant jet in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography's recommendation.14 In our study, significant VR was defined as regurgitation of more than a mild degree. Reversible VR was defined as significant VR at initial echocardiogram that appeared at follow‐up echocardiogram. In our study, we assessed the presence of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve using 2D imaging.15 Left atrial volume index was determined by the prolate ellipse method and indexed by body surface area.

N‐terminal Pro‐Brain Natriuretic Peptide Assay

We took blood samples from the antecubital vein using lithium heparin, and the blood samples were then centrifuged. The blood samples were stored at −70°C until further analysis. Plasma N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐pro BNP) assay levels were measured using an Elecsys pro‐BNP reagent kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and an Elecsys 2010 (Roche Dignostics). In all cases, the time interval between blood sampling for NT‐pro BNP and echocardiography was not over 1 day.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Age, heart rate, corrected QT interval, hs‐CRP, peak CK, peak CK‐MB, peak troponin‐I, left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP), duration of hospitalization, and duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay are given in terms of the median and interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative data are presented as frequencies. The Student t test or Mann‐Whitney test were used to compare the continuous variables, and the χ 2 test was used to compare the categorical variables. All P values are 2‐tailed, and differences were considered significant when the P value was <0.05.

Results

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between Inverted TTC and Other TTC

The clinical characteristics and initial presentations of the inverted TTC group and other TTC group are compared in Table 1. The inverted TTC group was younger (median, 54.5 vs 64.0 years; P = 0.006) and had a higher prevalence of triggering stress (100% vs 77%, P = 0.018) than the other TTC group, whereas the other TTC group had higher prevalence of dyspnea (58% vs 30%, P = 0.025), pulmonary edema (46% vs 20%, P = 0.035), and cardiogenic shock (36% vs 10%, P = 0.023) than inverted TTC.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between the Inverted TTC Group and Other Type TTC Group

| Inverted TTC Group (n = 20) | Other Type TTC Group (n = 83) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, ya | 54.5 (48.3–62.0) | 64.0 (53.0–72.0) | 0.006b |

| Male gender, n (%) | 10 (50) | 23 (28) | 0.060 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.864 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 4 (20) | 18 (22) | 0.869 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 4 (20) | 30 (36) | 0.168 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 0 (0) | 8 (9) | 0.148 |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (7) | 0.215 |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.483 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 2 (10) | 5 (6) | 0.526 |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 6 (30) | 12 (15) | 0.100 |

| Stress event, n (%) | 20 (100) | 64 (77) | 0.018b |

| Preceding physical stress, n (%) | 16 (80) | 53 (64) | 0.168 |

| Surgery/procedure, n (%) | 7 (35) | 21 (25) | 0.381 |

| Preceding emotional stress, n (%) | 4 (20) | 11 (13) | 0.443 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Chest pain, n (%) | 10 (50) | 40 (48) | 0.885 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 6 (30) | 48 (58) | 0.025b |

| Nausea, n (%) | 4 (20) | 6 (7) | 0.083 |

| Palpitation, n (%) | 2 (10) | 7 (8) | 0.824 |

| Pulmonary edema, n (%) | 4 (20) | 38 (46) | 0.035b |

| Cardiogenic shock, n (%) | 2 (10) | 30 (36) | 0.023b |

Presented as median (interquartile range).

Significant finding.

Comparison of ECG Changes, Laboratory, and Angiographic Findings Between Inverted TTC and Other TTC

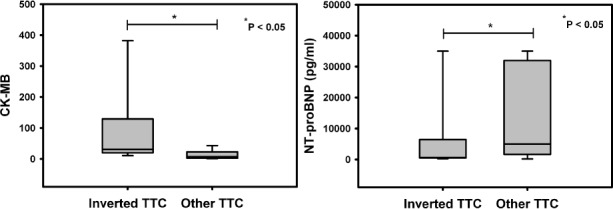

The ECG changes, laboratory, and angiographic findings of inverted TTC and other TTC are compared in Table 2. Inverted TTC had significant higher peak CK‐MB (median, 30.7 vs 7.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001) and troponin‐I (median, 13.1 vs 1.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001) than other TTC group, whereas other TTC group had significant NT‐proBNP levels (median, 613.3 vs 4987.0 pg/mL; P = 0.020) than inverted TTC (Figure 1). other TTC group had significantly higher prevalence of T‐wave inversion (81% vs 60%, P = 0.049) than inverted TTC. For angiographic findings, there were no significant differences in LVEDP levels between the two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of Electrocardiographic Changes, Laboratory, and Angiographic Findings Between the Inverted TTC Group and Other Type TTC Group

| Inverted TTC Group (n = 20) | Other Type TTC Group (n = 83) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiographic changes | |||

| Life‐threatening arrhythmia, n (%) | 4 (20) | 12 (15) | 0.539 |

| Heart rate (beats/min)a | 79.0 (69.0–87.0) | 80 (66.0–93.0) | 0.714 |

| Sinus rhythm, n (%) | 20 (100) | 77 (93) | 0.215 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (7) | 0.215 |

| Corrected QT interval (ms)a | 451.0 (415.0–497.0) | 434.0 (413.0–473.0) | 0.864 |

| ST‐segment elevation, n (%) | 11 (55) | 63 (76) | 0.062 |

| Q‐wave, n (%) | 5 (25) | 9 (11) | 0.097 |

| T‐wave inversion, n (%) | 12 (60) | 67 (81) | 0.049b |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| hs‐CRP (mg/L) | 2.2 (0.2–6.8) | 2.3 (0.9–11.8) | 0.469 |

| Cardiac enzymes | |||

| Peak CK (ng/mL)a | 896.5 (519.0–1880.0) | 221.0 (83.0–862.0) | 0.001b |

| Peak CK‐MB (ng/mL)a | 30.7 (19.6–128.9) | 7.6 (2.4–23.0) | 0.001b |

| Peak troponin‐I (ng/mL)a | 13.1 (3.6–101.7) | 1.6 (0.2–9.0) | 0.001b |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL)a | 613.3 (482.4–6404.5) | 4987.0 (1623.5–31962.0) | 0.020b |

| Angiographic findings | |||

| LVEDP (mmHg)a | 13.5 (10.0–23.0) | 19.0 (14.3–25.0) | 0.315 |

Abbreviations: CK, creatine kinase; CK‐MB, creatine kinase MB fraction; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure, NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide.

Life‐threatening arrhythmia: 3rd‐degree atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest.

Presented as median (interquartile range).

Significant finding.

Figure 1.

The cardiac enzyme and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) levels in inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) and other TTC groups. Inverted TTC had significantly higher peak creatine kinase MB fraction (CK‐MB) (median, 30.7 vs 7.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001) and troponin‐I (median, 13.1 vs 1.6 ng/mL; P = 0.001) than other TTC, whereas other TTC had significant NT‐proBNP levels (median, 613.3 vs 4987.0 pg/mL; P = 0.020) than inverted TTC.

Comparison of Echocardiographic Findings Between Inverted TTC and Other TTC

The echocardiographic findings of inverted TTC and other TTC are compared in Table 3. There were no significant differences in time intervals from initial presentation to initial echocardiography (median, 24 hours [IQR, 13–34 hours] in inverted TTC vs median, 12 hours [IQR, 7–25 hours] in other TTC; P = 0.124) and follow‐up echocardiography after clinical recovery (median, 13 days [IQR, 8–70 days] in inverted TTC vs median, 21 days [IQR, 10–80 days] in other TTC; P = 0.976) were not different between the two groups. The LVEF on the initial examination was 37.7 ± 10.1% in inverted TTC and 41.3 ± 7.4% in other TTC. Follow‐up echocardiogram after clinical recovery showed LVEF was 64.6 ± 5.4% in inverted TTC and 63.7 ± 4.6% in other TTC. The other TTC group had a higher prevalence of significant reversible mitral regurgitation (MR) than patients in inverted TTC (19% vs 0%, P = 0.033). All patients showed normalized regional wall motion in their follow‐up echocardiograms.

Table 3.

Comparison of Echocardiographic Findings Between the Inverted TTC Group and Other Type TTC Group

| Inverted TTC Group (n = 20) | Other Type TTC Group (n = 83) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial TTE findings | |||

| LVEF (%) | 37.7 ± 10.1 | 41.3 ± 7.4 | 0.388 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 50.1 ± 4.1 | 52.2 ± 6.5 | 0.175 |

| LVESD (mm) | 36.5 ± 7.4 | 37.0 ± 7.0 | 0.787 |

| LAVI (mL/m2) | 31.1 ± 21.6 | 27.5 ± 12.6 | 0.490 |

| RVSP (mmHg) | 32.9 ± 3.2 | 34.0 ± 3.7 | 0.221 |

| E/E′ | 10.0 ± 5.0 | 11.6 ± 6.8 | 0.608 |

| SAM | 0 (0) | 13 (16) | 0.058 |

| Significant MR, n (%) | 4 (20) | 21 (25) | 0.620 |

| Significant AR, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (7) | 0.215 |

| Significant TR, n (%) | 2 (10) | 15 (18) | 0.383 |

| Follow‐up TTE findings | |||

| LVEF (%) | 64.6 ± 5.4 | 63.7 ± 4.6 | 0.494 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 48.6 ± 4.2 | 49.9 ± 5.6 | 0.362 |

| LVESD (mm) | 30.4 ± 2.6 | 31.4 ± 4.4 | 0.211 |

| LAVI (mL/m2) | 31.7 ± 23.3 | 26.6 ± 11.3 | 0.414 |

| RVSP (mmHg) | 31.8 ± 4.7 | 31.0 ± 4.4 | 0.566 |

| E/E′ | 9.0 ± 3.2 | 10.7 ± 5.5 | 0.346 |

| SAM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Significant MR, n (%) | 4 (20) | 5 (6) | 0.047a |

| Reversible MR, n (%) | 0 (0) | 16 (19) | 0.033a |

| Significant AR, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (7) | 0.215 |

| Significant TR, n (%) | 2 (10) | 8 (10) | 0.961 |

Abbreviations: AR, aortic regurgitation; E/E′, early diastolic mitral inflow velocity/early diastolic annular velocity; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter; MR, mitral regurgitation; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; SAM, systolic anterior motion of anterior mitral leaflet; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

Significant finding.

The Comparison of Management and Clinical Outcomes Between Inverted TTC and Other TTC

Management and clinical outcomes were not significantly different between the groups (Table 4). There were no significant differences in the use of inotropics, use of intra‐aortic balloon pump (IABP), use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), use of β‐blockers, and use of diuretics during hospitalization between the two groups. Also, there were no significant differences in duration of hospitalization, or frequency and duration of ICU stay between the two groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of Clinical Courses and Management Between the Inverted TTC Group and Other Type TTC Group

| Inverted TTC Group (n = 20) | Other Type TTC Group (n = 83) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of inotropics, n (%) | 2 (10) | 26 (31) | 0.054 |

| Use of IABP, n (%) | 2 (10) | 10 (12) | 0.798 |

| Use of ACEI or ARB, n (%) | 8 (40) | 49 (59) | 0.124 |

| Use of β‐blocker, n (%) | 6 (30) | 15 (18) | 0.235 |

| Use of diuretic, n (%) | 8 (40) | 32 (39) | 0.905 |

| Temporal pacemaker, n (%) | 2 (10) | 8 (10) | 0.961 |

| ICU hospitalization, n (%) | 12 (60) | 51 (61) | 0.905 |

| ICU hospitalization (d)a | 2.5 (0–8.0) | 2.0 (0–5.0) | 0.938 |

| Hospitalization(d)a | 18.0 (11.0–26.0) | 9.0 (6.0–28.0) | 0.376 |

| In‐hospital cardiac mortality, n(%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Cardiac mortality during follow‐up, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Mortality during follow‐up, n (%) | 3 (15) | 9 (11) | 0.603 |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; IABP, intraaortic balloon pump; ARB; angiotensin receptor blocker; ICU, intensive care unit.

Presented as median (interquartile range).

During follow‐up (median, 3.1 years [IQR, 2.0–4.1 years]), 12 (12%) patients died. Six patients died of malignancy, 2 of stroke, 2 of chronic renal failure with panperitonitis, 1 of liver cirrhosis with variceal bleeding, and 1 died of pneumonia with empyema. However, cardiac deaths associated with TTC itself and the recurrence of the TTC were not noted in either group.

Discussion

When TTC was first described, it was referred to as transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome because all patients had characteristic akinesia and ballooning of the apex, midventricular dysfunction, and a normal or hypercontractile basal segment.1, 2, 3, 4 New variants of TTC, such as inverted TTC and midventricular ballooning syndrome, have recently been described in a few published reports.5, 6, 7, 8 The purpose of this study was to explore and investigate the various characteristics of different types of TTC that have been described in detail in the first works of Ramaraj et al.10 For the first time, Ramaraj et al have demonstrated that patients with the reverse type were significantly younger compared with those with other types of TTC (mean age, 36 years for reverse vs 62 years for other types).10 Similar to the results of the aforementioned first report,10 our study showed patients with inverted TTC presented at an early age compared with those with other types of TTC (median age, 54.5 years for inverted versus 64.0 years for other types). Some studies reported that adrenoreceptor density was highest in the apex compared with the base in postmenopausal women, which explains the occurrence of the apical variant in older women.10, 16, 17, 18 Ramaraj et al hypothesized that the presentation of inverted TTC at a young age might be due to the abundance of adrenoceptors at the base compared to the apex at a younger age.10 Based on these observations, we supposed that the differences in the location or amount of adrenoceptor with aging may affect different ballooning patterns of TTC. For the first time, Ramaraj et al have demonstrated that all patients with the reverse type had either physical or mental stress, whereas 15% of those with other types had no triggering stress. In accordance with the results of aforementioned first report,10 our data showed that all patients with inverted TTC had triggering stress in comparison with 23% of those with apical or midvariant that could present without any trigger.

A notable finding in our study was that 18 (17%) among 103 enrolled patients had a history of cancer at the index hospitalization for TTC. Our finding may support the results of recently published reports showing the 23.6% of patients with TTC had cancer, which greatly exceeds the expected prevalence of cancer in age‐matched populations in the United States (8.2%), Germany (11.2%), and all European countries combined (7.8%).19, 20 Burgdorf et al suggested increased basal sympathetic tone in patients with cancer may be associated with susceptibility to TTC with additional stress as well as paraneoplastic mediators directly alteringcardiac adrenoreceptors.19, 20

Interestingly, in our study, patients with apical or mid‐TTC presented with more severe heart failure symptoms, such as dyspnea and cardiogenic shock, than those with the inverted variant. These findings were similar to the findings of previous reports.9, 18, 21 These findings may suggest that differences in the clinical features concomitant with possible hemodynamic changes may be attributed to the differences in location of regional wall motion abnormality, and the inverted variant may be another manifestation of classic type TTC. In accordance with previous reports,9, 18, 21 patients with apical or mid‐TTC had higher prevalence of T‐wave inversion than those with inverted TTC. It has been suggested that the differences in clinical features and ECG findings may be related to the location of the LV ballooning.9, 18, 21 Therefore, these findings may suggest that the LV apex may be not a specific site of involvement, but may be a site that produces characteristic symptoms and signs of TTC in spite of a preponderance of apical ballooning. In addition, because patients with inverted TTC presented at an early age compared with those with other TTC, age difference could have accounted for the differences in clinical features and ECG findings.

A remarkable finding of our study was that apical or mid‐TTC had significantly higher prevalence of significant reversible MR and higher NT‐proBNP levels than the inverted variant. The possible mechanism of acute reversible MR seems to lie in the altered spatial relationship between mitral leaflets and subvalvular apparatus caused by apical ballooning.21, 22, 23 In contrast with the inverted variant (0%), the SAM occurred in 16% of patients with apical or mid‐TTC and appeared to play a relevant role in determining the presence of reversible MR during acute phase of TTC. According to previous studies,24, 25, 26, 27 dynamic LV outflow tract obstruction concomitant with basal hypercontraction was associated with hemodynamic instability in patients with classic TTC. Based on the findings of aforementioned studies,9, 21, 24, 25 in addition to the results of the present study, we reasoned that even if the presence of functional MR with possible dynamic outflow obstruction may not be fully enough to explain higher NT‐proBNP levels and more severe heart failure symptoms, functional MR may be an important exacerbating factor in heart failure symptoms and signs in patients with apical or mid‐TTC. Moreover, according to recently published studies,21, 24, 25 increased wall stress due to dynamic outflow tract obstruction may be important factors in exacerbating heart failure symptoms and producing higher levels of NT‐proBNP levels in patients with apical or mid‐TTC.

Interestingly, in the present study, inverted TTC had significantly higher levels of cardiac markers, such as CK‐MB andtroponin‐I, than patients with apical or mid‐TTC, although there were no significant differences in the overall LVEF between the groups. The possible explanation is that patients with inverted TTC may have the greater extent of affected myocardium than patients with apicalor mid‐TTC. Apical or mid‐TTC involves apical or midventricular segments concomitant with hypercontractility in basal segments, whereas a novel syndrome of inverted TTC involves basaland mid segments with preserved contractility of apical segments.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Therefore, the inverted TTC variant has the greater extent of affected myocardium and cardiac markers, such as CK‐MB andtroponin‐I, and may reflect this extent of affected myocardium.

In contrast with the results of previously published study,28 demonstrating the diagnosis of TTC appears to be unlikely in patients with troponin T >6 ng/mL and troponin I >15 ng/mL, 20 patients enrolled in our study had troponin I >15 ng/mL. It is therefore important to perform meticulous work‐up and treatment regardless of CK‐MB and troponin levels in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Notably, in our study there were no differences in the use of inotropic agents, IABP, use of ACEI or ARB, use of β‐blockers and diuretics, and duration of hospitalization and ICU stay between the Inverted group and other TTC group. It has been reported that the use of inotropic agents, particularly in patients with shock, may increase the gradient and worsen cardiogenic shock in patients with TTC.27, 29, 30, 31 Therefore, it seems likely that cardiogenic shock is treated with standard therapies such inotropes and IABP, although a cautious trial of intravenous fluids and β‐blockers may improve hemodynamic instability in patients with apical or mid variant.

In the present study, the overall mortality (12%) was relatively higher than in previous studies.1, 2, 3, 4 However, the overall mortality associated with TTC itself was 0%. This excellent prognosis of TTC was comparable to results of published reports in other areas of the world.1, 2, 3, 4

Study Limitations

There are some limitations that should be considered in our study. First, this was a retrospective analysis. However, we prospectively enrolled TTC patients from the year 2000, and most patients were diagnosed and managed by protocol. Second, the results of our study may be limited by the relatively small number of enrolled patients; this is particularly true for the inverted TTC group. Third, we did not perform systemic investigations such ascatecholamine measurements, magnetic resonance imaging, viral antibody titers, or pathology.

Conclusion

Inverted TTC presents at a younger age and has a higher prevalence of triggering stress, whereas apical or mid‐TTC has a higher prevalence of heart failure symptoms, significant MR, and T‐wave inversion and higher NT‐proBNP levels despite other clinical features that are mostly similar.

References

- 1. Abe Y, Kondo M, Matsuoka R, et al. Assessment of clinical features in transient left ventricular apical ballooning. J Am CollCardiol. 2003;41:737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, et al. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1523–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, et al. Tako‐tsubo‐like left ventricular dysfunction with ST‐segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee YP, Poh KK, Lee CH, et al. Diverse clinical spectrum of stress‐induced cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:272–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Movahed MR, Donohue D. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning, broken heart syndrome, ampulla cardiomyopathy, atypical apical ballooning, or Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy [review]. CardiovascRevasc Med. 2007;8:289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurst RT, Askew JW, Reuss CS, et al. Transient midventricular ballooning syndrome: a new variant. J Am CollCardiol. 2006;48: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haghi D, Papavassiliu T, Fluchter S, et al. Variant form of the acute apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo cardiomyopathy): observations on a novel entity. Heart. 2006;92:392–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hahn JY, Gwon HC, Park SW, et al. The clinical features of transient left ventricular nonapical ballooning syndrome: comparison with apical ballooning syndrome. Am Heart J. 2007;154:1166–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramaraj R, Movahed MR. Reverse or inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy (reverse left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) presents at a younger age compared with the mid or apical variant and is always associated with triggering stress. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16:284–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Menon V, White H, LeJemtel T, et al. The clinical profile of patients with suspected cardiogenic shock due to predominant left ventricular failure: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries in cadiogenicshocK? J Am CollCardiol. 2000;36:1071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hackett D, Larkin S, Chierchia S, et al. Induction of coronary artery spasm by a direct local action of ergonovine. Circulation. 1987;75:577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al; Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am SocEchocardiogr. 2005;18: 1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two‐dimensional and doppler echocardiography. J Am SocEchocardiogr. 2003;16:777–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El Mahmoud R, Mansencal N, Pilliere R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in Tako‐Tsubo syndrome. Am Heart J. 2008;156:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cocco G, Chu D. Stress induced cardiomyopathy: a review. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18:369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindsay J, Paixao A, Chao T, et al. Pathogenesis of the Takotsubo syndrome: a unifying hypothesis. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106: 1360–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pernicova I, Garg S, Bourantas CV, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a review of the literature. Angiology. 2010;61:166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgdorf C, Nef HM, Haghi D, et al. Takotsubo (stress‐induced) cardiomyopathy and cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152: 830–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burgdorf C, Kurowski V, Bonnemeier H, et al. Long‐term prognosis of the transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy): focus on malignancies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:1015–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Song BG, Park SJ, Noh HJ, et al. Clinical characteristics, and laboratory and echocardiographic findings in takotsubo cardiomyopathy presenting as cardiogenic shock. J Crit Care. 2010;25:329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valbusa A, Abbadessa F, Giachero C, et al. Long‐term follow‐up of Tako‐Tsubo‐like syndrome: a retrospective study of 22 cases. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2008;9:805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levine RA, Vlahakes GJ, Lefebvre X, et al. Papillary muscle displacement causes systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. Experimental validation and insights into the mechanism of subaortic obstruction. Circulation. 1995;91:1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desmet W. Dynamic LV obstruction in apical ballooning syndrome: the chicken or the egg. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Merli E, Sutcliffe S, Gori M, et al. Tako‐Tsubo cardiomyopathy: new insights into the possible underlying pathophysiology. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Penas‐Lado M, Barriales‐villa R, Goicolea J. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning and outflow tract obstruction. J Am CollCardiol. 2003;42:1143–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brunetti ND, Ieva R, Rossi G, et al. Ventricular outflow tract obstruction, systolic anterior motion and acute mitral regurgitation in Tako‐Tsubo syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramaraj R, Sorrell VL, Movahed MR. Levels of troponin release can aid in the early exclusion of stress‐induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. ExpClinCardiol. 2009;14:6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kyuuma M, Tsuchihashi K, Shinshi Y, et al. Effect of intravenous propranolol on left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis (ampulla cardiomyopathy)‐three cases. Circ J. 2002;66:1181–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoshioka T, Hashimoto A, Tsuchihashi K, et al. Clinical implications of midventricular obstruction and intravenous propanolol use in transient left ventricular apical ballooning (Tako‐tsubo cardiomyopathy). Am Heart J. 2008;155:526;e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Migliore F, Bilato C, Isabella G, et al. Hemodynamic effects of acute intravenous metoprolol in apical ballooning syndrome with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;13:305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]