Abstract

Background:

Echocardiographic parameters could be implicated in the development of apical asynergy (characterized by apical sequestration or apical aneurysm) and worse cardiovascular outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (ApHCM).

Hypothesis:

Echocardiographic parameters and morphological patterns of left ventriculograms are associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with ApHCM.

Methods:

We followed 47 cases with echocardiographically documented ApHCM. Echocardiographic findings of the extent and degree of hypertrophy, sustained cavity obliteration, and paradoxical diastolic jet flow were measured. All patients underwent a cardiac catheterization except for the cases whose informed consent was not acquired. The clinical manifestations were assessed and recorded by the attending physicians during 35.4 ± 23.7 months follow‐up.

Results:

Among the 47 patients with ApHCM, 30 patients presented as the “pure” form and 17 patients present as the “mixed” form. Seventeen of 28 patients with sustained cavity obliteration showed paradoxical flow by echocardiography. Thirty‐one underwent left ventriculograms and showed morphological abnormalities, including “ace‐of‐spades” configuration (15/31), apical sequestration (12/31), and apical aneurysm (4/31). The results demonstrated that cardiovascular morbidities occurred in 21 of 47 patients and were closely related to the presence of mixed form ApHCM, cavity obliteration, and paradoxical flow by univariate and multivariate Cox analysis. During the period of follow‐up, 4 patients (9.5%) died, and among them 3 had concomitant apical aneurysm.

Conclusions:

We concluded that detection of cavity obliteration and paradoxical flow and discrimination of pure form from mixed form by echocardiography, as well apical sequestration from apical aneurysm in ApHCM patients, is warranted. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

This work was supported in part by grants from Lo‐Tung Poh‐Ai Hospital. The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (ApHCM) is characterized by hypertrophy of the myocardium, predominantly in the left ventricular apex. This relatively rare variant of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is common in Japanese and other Asian populations.1 Typical features of ApHCM include giant negative T waves on electrocardiography (ECG), mild symptoms, and a generally more benign course with a lower mortality rate than other forms of HCM.2 Two‐dimensional echocardiography (2D echo) is currently the standard tool for the clinical diagnosis of ApHCM. The patients are subdivided into 2 groups based on whether they have isolated asymmetric apical hypertrophy—“ pure” ApHCM—or have a coexistent hypertrophy of the interventricular septum—“mixed” ApHCM. Patients with the mixed form ApHCM compared with the pure form ApHCM have unfavorable echocardiographic presentations,3 but the clinical outcome data are lacking. In addition, several reports described a wide spectrum of morphological appearances of this disease, including cavity obliteration (CO), apical sequestration (ApSeq), and apical aneurysm (ApAn). Sustained CO and paradoxical diastolic flow jet (PF) detected by echocardiography have been implicated in the development of apical asynergy and the risk of adverse clinical events in these patients.4 However, whether ApSeq contributes to morbidity or mortality and whether there is a greater number of adverse clinical features in ApHCM patients with CO, PF, and apical asynergy remains to be clarified. Currently, cardiac catheterization is not a routine examination in ApHCM patients, but is frequently undergone due to similarity in symptoms and ECG findings with coronary artery disease (CAD). A “spade‐shaped” configuration of the left ventricle (LV) cavity at end‐diastole is characteristic on left ventriculograms (LVG). In addition, LVG is the gold standard for diagnosing ApAn and ApSeq. Therefore, the aim of performing LVG in the present study was the validation of echo parameters as surrogates for apical asynergy and in turn be routinely used as risk stratification of ApHCM patients. Based on the distinction between the pure and mixed form ApHCM and markers of apical asynergy (existence of CO and PF) by using echocardiography, and differentiate ApSeq from ApAn by using LVG, the purpose of this study was to assess the correlations of these parameters with cardiovascular morbidity (including syncope, heart failure, nonfatal arrhythmias, and stroke) and mortality.

Methods

Study Population and Study Design

Between 2003 and 2008, 47 consecutive patients (60.2 ± 14.9 years old; 29 male) with echocardiographically documented ApHCM were enrolled from Lo‐Tung Poh‐Ai general hospital in Yi‐Lan County. All patients received serial 12‐lead ECG and echocardiographic evaluations and 24 hour Holter monitoring if clinically indicated. All patients were scheduled to undergo cardiac catheterization except for the cases whose informed consent was not acquired. The clinical manifestations were assessed and recorded in the outpatient follow‐up by the attending physicians. Results of these evaluations, as well as clinical manifestations, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality were analyzed.

Definitions

The diagnostic criteria for ApHCM were based on the 2D echo demonstration of LV hypertrophy predominantly in the region of the LV apex, with a wall thickness ≥15 mm and a ratio of apical to posterior wall thickness ≥1.5. ApHCM cases were further separated into pure and mixed type. The pure form was defined as hypertrophy limited to the apical portion of the LV below the papillary muscle level, whereas the mixed form had a coexistent hypertrophy of the other segments.5 Giant negative T‐wave was defined as an inverted T wave ≥10 mm in depth, in addition to tall R waves in the precordial ECG leads.1

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic studies were performed with a 2.5 MHz transducer connected to an ultrasound system (SONOS 5500; Philips, MA; USA). On M‐mode recordings, we measured left atrial diameter, and end‐systolic and end‐diastolic dimensions of the LV base and apex. CO was defined as complete end‐systolic cavity obliteration at the papillary muscle level on the short‐axis view of 2D echo. PF was defined as a high‐velocity turbulence signal occurring during diastole originating from the apex and persisting after the onset of diastolic filling (Figure 1).4

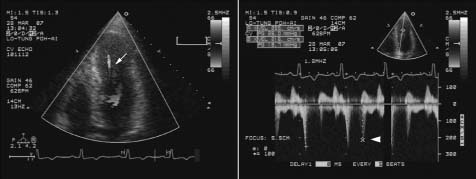

Figure 1.

Color Doppler echocardiography revealed an intraventricular turbulent flow from the apex to the left ventricle outflow during early diastole caused by paradoxical diastolic jet flow (arrow, left panel) with a peak flow velocity of 2.55 m/s (arrowhead, right panel).

Cardiac Catheterization

Thirty‐one patients in our study population underwent cardiac catheterization. The time interval between catheterization and echocardiographic examination was 9 ± 8 days. LVG was performed in the right and left anterior oblique projection. Selective coronary angiograms were obtained in multiple projections. These patients were categorized into 3 types according to the morphology of LVG: (1) typical “ace‐of‐spades” configuration, (2) ApSeq, and (3) ApAn. ApSeq is, by definition, “a small sequestration at the apex connected to the main chamber by a narrow muscular tunnel that completely disappeared during contraction.”6 LV apical aneurysm was defined as a discrete thin‐walled dyskinetic or akinetic segment of the most distal portion of the chamber with a relatively wide communication to the LV cavity.7 Figure 2 illustrates the 3 types of LVG.

Figure 2.

Left ventriculogram in the right anterior oblique view. (A) The typical spade‐like appearance at end‐diastole. (B) During end‐systole a small cavity in the apical portion (arrow) was separated from the basal cavity by long cavity obliteration. (C) During end‐diastole the apical aneurysm was communicated with the left ventricle (LV) and showed an hourglass‐shaped LV cavity.

Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity

The definition of ApHCM‐related causes of death included heart failure, ischemic stroke, cardiac arrest‐related arrhythmias, and sudden death (unexpected sudden collapse). ApHCM‐related cardiovascular morbidity was defined as cases for which the occurrence of the following events resulted in hospitalization: presyncope or syncope (of undetermined cause), heart failure (≥ New York Heart Association Functional Class II), nonfatal arrhythmia, stroke related to atrial fibrillation, and acute myocardial infarction unrelated to CAD.8 The diagnosis of myocardial infarction was established in the presence of characteristic symptoms, typical pattern on ECG, and elevated cardiac enzymes.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Data are expressed as mean ±SD, or number of patients. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference. Potential confounding factors of developing ApHCM‐related morbidities were assessed with univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis (the hazard ratio and its associated 95% confidence interval). Analysis was done with SPSS software version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Clinical Features, ECG, and Echocardiographic Characteristics

Baseline clinical features of the 47 patients with ApHCM are listed in Table 1. The major clinical manifestation in our study population was chest pain or tightness (28/47, 59.6% of patients). Twenty‐one patients (44.7%) had concurrent hypertension. The classical giant negative T‐wave was found in 28 (59.6%) patients. There were 30 patients (63.8%) with the pure form and 17 patients (36.2%) with the mixed form of ApHCM. Patients with the mixed form ApHCM had more history of hypertension (P = 0.038) and left atrium dilatation (dimension ≥40 mm, P = 0.014) compared with the pure form ApHCM.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the 47 Patients With Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

| Features | All Patients |

|---|---|

| Men/women | 29/18 |

| Age (y) | 60.2 ± 14.9 |

| Family history of ApHCM | 5 (10.6) |

| History of hypertension | 21 (44.7) |

| Electrocardiography | |

| Normal ECG | 1 (2.1) |

| LV hypertrophy sign | 45 (95.7) |

| Giant negative T waves | 28 (59.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (14.9) |

| VT/VF | 2/2 (8.5) |

| Echocardiography | |

| Intraventricular septum thickness (mm) | 14.8 ± 3.8 |

| Posterior wall thickness (mm) | 12.2 ± 1.6 |

| Apical maximal thickness (mm) | 20.6 ± 2.7 |

| LAD (mm) | 38.9 ± 6.7 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 46.7 ± 3.8 |

| LVEF (%) | 67.2 ± 7.1 |

| Pure/mixed form | 30/17 |

| Cavity obliteration | 29 (61.7) |

| Diastolic paradoxical flow jet | 18 (38.3) |

| Cardiac catheterization (n = 31) | |

| Ace‐of‐spades configuration | 15 (48.4) |

| Apical sequestration | 12 (38.7) |

| Apical aneurysm | 4 (12.9) |

| Coronary artery disease | 11 (35.5) |

| Myocardial bridge | 1 (3.2) |

Abbreviations: ApHCM, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ECG, electrocardiography; LAD, left atrium dimension; LVEDD, LV end‐diastolic dimension; LVEF, LV ejective fraction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Data are presented as number of patients or mean value ± SD. Figures in parentheses are percentages.

Angiographic Findings

Thirty‐one of the 47 patients underwent coronary and LV angiography. The numbers of cases according to the morphologic pattern of LVG were 15 (48.4%) with ace‐of‐spades configuration, 12 (38.7%) with ApSeq, and 4 (12.9%) with ApAn. Apical asynergy was seen in all patients with ApSeq and ApAn. Significant coronary stenosis (>50% of 1 or more coronary arteries) was detected in 11 cases (35.5%). One patient with ace‐of‐spades LVG had a history of old inferior wall myocardial infarction. Patients with apical asynergy have a tendency to be of younger age than the spades type of LVG in our population (57.9 ± 19.0 vs 60.6 ± 12.4 years, P = 0.079), whereas the mean age of patients with ApAn was 47.8 ± 22.2 years.

Correlations Between Echocardiographic and Angiographic Findings

The diagnostic scheme is shown in Figure 3. Twenty‐one patients with sustained CO and 10 patients without sustained CO underwent LVG, and the distribution of morphological patterns is demonstrated. Sustained CO was seen in 28 patients (59.6%); among them 17 showed PF. Twelve patients with both CO and PF exhibited LV asynergy angiographically (P < 0.0001, compared with patients without PF). Patients with CO, regardless of the presence or absence of PF, more often exhibited LV asynergy (14/17) compared with those without CO (odds ratio [OR]: 8.0, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.33–48.18, P = 0.02) (Table 2).

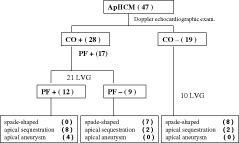

Figure 3.

In this diagnostic scheme, 21 patients with sustained cavity obliteration (CO) and 10 patients without sustained CO underwent left ventriculogram (LVG) and the distribution of morphological patterns is demonstrated. Figures in parentheses are patient numbers. Abbreviations: ApHCM, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; PF, paradoxical diastolic jet flow.

Table 2.

Predictive factors for the Configurations of Left Ventriculogram in 31 Patients Undergoing Cardiac Catheterization

| Ace‐of‐Spades | ApSeq + ApAn | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.58a | ||

| Male (n = 17) | 9 | 8 | |

| Female (n = 14) | 6 | 8 | |

| Age (years) | 60.6 ± 12.4 | 57.9 ± 19.0 | 0.58b |

| Hypertension | 0.35a | ||

| (+) n = 13 | 5 | 8 | |

| (−) n = 18 | 10 | 8 | |

| LAD | 0.85a | ||

| (≥40 mm) n = 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| (<40 mm) n = 16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Pure form ApHCM (n = 23) | 13 | 10 | 0.22c |

| Mixed form ApHCM (n = 8) | 2 | 6 | |

| Apical thickness | 0.11a | ||

| 20 mm | 6 | 11 | |

| <20 mm | 9 | 5 | |

| CO (+), n = 21 | 7 | 14 | 0.02c |

| CO (−), n = 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| PF (+), n = 12 | 0 | 12 | <0.0001c |

| PF (−), n = 19 | 15 | 4 |

Abbreviations: ApAn, apical aneurysm; ApHCM, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ApSeq, apical sequestration; CO, cavity obliteration; LAD, left atrium dilatation; LVG, left ventriculogram; PF, paradoxical diastolic jet flow.

χ 2 test.

2‐sample test.

Fisher exact test.

Clinical Outcome (Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity)

There were 33 morbid cardiovascular events, including atrial fibrillation (n = 7), congestive heart failure (n = 12), unexplained syncope (n = 5), stroke (n = 5), acute myocardial infarction unrelated to CAD (n = 2), and ventricular tachycardia (VT) (n = 2). These morbid events occurred in 21/47 patients (44.7%). In a univariate analysis model (Table 3), there were significant associations between higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mixed form ApHCM (OR: 3.67, 95% CI: 1.05–12.81, P = 0.042, compared with pure form), presence of PF (OR: 4.44, 95% CI: 1.27–15.61, P = 0.020, compared with no PF), and presence of CO (OR: 4.96, 95% CI: 1.31–18.83, P = 0.019, compared with no CO), respectively. LV asynergy (ApSeq or ApAn on LVG) had a tendency of statistic significance (OR: 4.58, P = 0.051, compared with ace‐of‐spades configuration) for the risk of morbidity. In a multivariate analysis model, the presence of PF and CO was the independent predictor of higher risk for cardiovascular morbidity (Table 3). Over the follow‐up period of 35.4 ± 23.7 months, 4 patients (8.5%) died, including 3 of the 4 patients with ApAn (1 caused by CVA and 2 by sudden death with ECG documented ventricular fibrillation), and another was due to acute lung edema (no LVG data). The only surviving patient with ApAn had experienced episodes of sustained VT. There was no mortality in patients with 'ace‐of‐spades and ApSeq LV configuration. Patients with mixed form ApHCM had tendency for statistical significance of LV asynergy (OR: 3.9, P = 0.14) compared with the pure form ApHCM.

Table 3.

Predictive Factors of Cardiovascular Morbidity Among 47 Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients

| Predictive Factors | Odds Ratio | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Female | 2.04 (0.148–1.614) | 0.240 |

| Hypertension | 1.24 (0.390–3.943) | 0.716 |

| Left atrium dilatation (≥40 mm) | 2.13 (0.661–6.880) | 0.758 |

| Mixed form ApHCM | 3.67 (1.04–12.813) | 0.042 |

| Apical thickness(≥20 mm) | 1.19 (0.368–3.859) | 0.770 |

| Cavity obliteration | 4.96 (1.305–18.832) | 0.019 |

| Diastolic paradoxical jet flow | 4.44 (1.265–15.612) | 0.020 |

| Apical asynergy | 4.58 (0.981–14.292) | 0.051 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Model 1 | ||

| Mixed form ApHCM | 3.47 (0.915–13.137) | 0.067 |

| Cavity obliteration | 4.73 (1.183–18.927) | 0.028 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Mixed form ApHCM | 3.03 (0.813–11.299) | 0.099 |

| Diastolic paradoxical jet flow | 3.80 (1.036–13.946) | 0.044 |

Abbreviations: ApHCM, apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Figures in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. Model 1 and 2 are required because cavity obliteration is a requisite for diastolic paradoxical jet flow.

Clinical Outcome in ApHCM Patients Coexisting With CAD

CAD was detected in 11 of 31 patients undergoing coronary angiography, and 1 patient had myocardial bridging. All patients with severe CAD were treated with a percutaneous coronary intervention (n = 10) or bypass graft surgery (n = 1). There was 1 death caused by stroke in ApHCM patients coexisting with CAD. The mixed form ApHCM compared with pure form ApHCM had a tendency of significant CAD (relative risk: 4.72, 95% CI: 0.86–26.04, P = 0.075). In the present study, coexisting CAD in ApHCM patients could not be used as an additional prognostic factor for overall mortality and morbidity.

Discussion

The data from the present study demonstrate the close correlations between CO, PF, angiographic LV morphology, and adverse major events in patients with ApHCM. We concluded that cardiovascular morbidity was closely related to the presence of the mixed form ApHCM, CO, PF, and apical asynergy. Both CO and PF predict existence of apical asynergy (ApSeq or ApAn on LVG) and cardiovascular morbidity in our cohorts. To the best of our knowledge, such an analysis has not been described previously in ApHCM studies. The present study also demonstrated that angiographic apical asynergy (ApSeq and ApAn) were more relevant to morbidity and mortality compared with ace‐of‐spades in LV configuration. Among the 4 mortalities in our cohort, 3 had ApAn and 2 had ECG‐documented ventricular fibrillation. The only surviving patient with ApAn had experienced episodes of sustained VT.

Thus, patients with ApAn have more ventricular tachyarrhythmias and greater mortality, but none of the patients with ApSeq and a spade‐shape on LVG did. In patients with ApSeq, despite it being frequently related to various morbidities,6 fatal outcomes have seldom been reported. Accordingly, the discrimination of ApSeq from ApAn should be pursued in ApHCM patients with apical asynergy. However, there was no distinction between ApSeq from ApAn in Nakamura et al's studies of HCM,4, 9 or in prior angiographic studies. Indeed, insufficient data are available for the prevalence, detection, and clinical implication of ApSeq in ApHCM. In a Taiwanese cohort study of ApHCM, Lee et al reported that the spade‐like deformity was the only presentation on the LVG, and ApSeq, ApAn, or mortality were not found.10 In contrast, in our cohort a high prevalence of ApSeq (12/31, 38.7%) and ApAn (4/31, 12.9%) exists. According to a previous report, ApAn was observed in approximately 10% of ApHCM patients,8 suggesting that ApAn is not rare and is underdiagnosed.

The prognosis is relatively favorable in most, but not all, ApHCM patients. ApHCM usually has a benign prognosis in Japan, and sudden death is rarely encountered.2 In contrast, in western countries, one third of ApHCM patients may develop unfavorable clinical events and potentially life‐threatening complications, such as myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmias, and stroke.8 Nevertheless, risk stratification of ApHCM patients is difficult by clinical evaluation. All patients with ApAn in our cohort had poor outcomes (3 deaths and 1 sustained VT), and 58.3% (7/12) patients with ApSeq had various morbidities. However, there is a lack of early diagnostic and early therapeutic strategy for ApHCM patients associated with ApSeq or ApAn. Currently, the LVG is the gold standard for diagnosing ApAn and ApSeq. The apical akinetic chamber and small sequestration are difficult to visualize due to massive hypertrophy on 2D echo,2 but can be discerned by the presence of CO and PF. As a result, based on detailed echocardiographic study, mixed form ApHCM, CO, and PF could be a simple parameter for the identification of the severity and outcome in ApHCM patients.

Why the mixed form ApHCM can predict higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity compared with apical form ApHCM in the study cohort remains unclear. Indeed, ApHCM may present various degrees and extent of LV hypertrophy (including mixed form phenotype) by detailed echocardiographic examination, which is important in the prediction of clinical or electromechanical characteristics.3

Our study population showed a later onset of presentation (60.2 ± 14.9 years) compared with previous studies, which reported a mean age of 44 to 47 years. There were 15 patients (32.0%) >70 years old and 8 patients (17.0%) >80 years old, which may reflect the older population in an agricultural country, but also suggests ApHCM patients without exacerbation (to apical asynergy) may have a benign course. In contrast, the 2 cases with apical aneurysm who suffered from sudden death were <33 years of age. Patients with apical asynergy have a tendency to be younger than the spade type of LVG in our population. Thus, one can suppose that some patients in whom disease progress continues may find their disease exacerbating rapidly at early stages with higher risk of fatal events, which may be determined by genetic factors.11

Conclusion

Unlike the presentation of ApHCM among the previous Taiwanese cohort study,10 this group of patients showed a higher prevalence of ApSeq and ApAn and a 9.5% mortality rate. Notably, we also find that the mixed form ApHCM can predict higher risk of cardiovascular morbidity compared with the apical form ApHCM. There were close correlations between CO, PF, angiographic apical asynergy, and adverse major cardiovascular events. Accordingly, routine follow‐up for assessment of CO, PF, and apical asynergy should be taken into consideration. When sustained CO and PF are found by echocardiography, additional effort of LVG for the identification of apical asynergy could be omitted without indication for the exclusion of CAD. In this regard, additional studies are warranted to determine the necessity and best methods for early detection of ApSeq and for discrimination from ApAn (such as cardiac magnetic resonance and multislice computed tomography).12 Patients with ApAn had disastrous outcomes necessitating close follow‐up and treatment. The high prevalence and relatively unfavorable clinical presentation of ApSeq in our study still needs to be clarified.

Limitations

Several issues limit our current results. First, the results of the present study were from a single geographic area in Taiwan. The study participants were all symptomatic, with more typical ECG and echocardiographic abnormalities, which are similar to the characteristics of the Japanese type ApHCM. Consequently, the fact that a non‐spade configuration on the LVG was not found in our series may be due to patient selection. Therefore, it cannot stand for the general ApHCM population in Taiwan. Second, one third of our ApHCM patients had concomitant CAD, which may affect the echocardiogram or LVG data and portray a significant bias. However, after appropriate revascularization, there was neither overt ischemia nor anterior myocardial infarction, which may influence the systolic function of the apex. That concomitant CAD did not influence the clinical features and outcomes for our cohort may be due to the exclusion of angina as an endpoint of morbidity. Third, we did not perform Holter ECG monitoring or myocardial perfusion imaging routinely unless it was clinically indicated. Therefore, we have no complete data on the incidence of arrhythmic events, radionuclear, and angiographic data. Finally, we did not perform Cox regression analysis for the predictive factors of mortality because the number of fatal events was too small to allow a reliable statistical analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the patients who participated in the study and the members of the echocardiography and catheterization laboratory who helped with this trial. We also appreciate Ms. Tseng‐Yi Hsiao for helping with statistical analysis.

References

- 1. Sakamoto T, Tei C, Murayama M, et al. Giant T wave inversion as a manifestation of asymmetrical apical hypertrophy (AAH) of the left ventricle. Echocardiographic and ultrasono‐cardiotomographic study. Jpn Heart J. 1976;17:611–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sakamoto T. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (apical hypertrophy): an overview. J Cardiol 2001;37(suppl 1):161–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eui‐Young Choi, Se‐Joong Rim, Jong‐Won Ha, et al. Phenotypic spectrum and clinical characteristics of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Multicenter Echo‐Doppler Study. Cardiology. 2008;110:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nakamura T, Matsubara K, Furukawa K, et al. Diastolic paradoxic jet flow in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evidence of concealed apical asynergy with cavity obliteration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Louie EK, Maron BJ. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: clinical and two‐dimensional echocardiographic assessment. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura T, Matsubara K, Furukawa K, et al. Apical sequestration in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: its clinical features and pathophysiology. J Cardiol. 1991;21:361–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Toda G, Iliev II, Kawahara F, et al. Left ventricular aneurysm without coronary artery disease, incidence and clinical features: clinical analysis of 11 cases. Intern Med. 2000;39:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long‐term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsubara K, Nakamura T, Kuribayashi T, et al. Sustained cavity obliteration and apical aneurysm formation in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee CH, Liu PY, Lin LJ, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Taiwan. Cardiology. 2006;106:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abinader EG, Sharif D, Shefer A, et al. Novel insights into the natural history of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy during long‐term follow‐up. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen CC, Chen MT, Lei MH, et al. Assessing myocardial bridging and left ventricular configuration by 64‐slice computed tomography in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy presenting with chest pain. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]