Abstract

Engineering advancements have expanded the role for mechanical circulatory support devices in the patient with heart failure. More patients with mechanical circulatory support are being discharged from the implanting institution and will be seen by clinicians outside the immediate surgical or heart‐failure team. This review provides a practical understanding of device design and physiology, general troubleshooting, and limitations and complications for implantable left ventricular assist devices (pulsatile‐flow and continuous‐flow pumps) and the total artificial heart. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Dr. Vigneshwar Kasirajan and Dr. Michael Hess receives a consulting honorarium from SynCardia Systems, Inc. The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Cardiac transplantation remains the sole long‐term successful therapy for end‐stage heart failure (HF), with the median survival reported to be >10 years.1 However, limited organ availability and increasing numbers of patients with advanced HF have served as a major impetus for the development of implantable mechanical assist devices.

Engineering advancements have expanded the role for mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices for patients with HF. Traditionally, MCS has been used to rescue hemodynamically deteriorating patients to recovery or as a bridge to transplantation. Today, use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) has expanded to severely symptomatic patients ineligible for heart transplantation (eg, patients with renal insufficiency, malnutrition, or secondary pulmonary hypertension) as long‐term therapy to improve their candidacy or as definitive (destination) therapy.

Irrespective of the indication, with technological improvements and increasing numbers of device implantations, more patients with MCS are being discharged from implanting institutions and will be seen by cardiologists outside the immediate surgical or HF team. Patients with MCS frequently visit the echocardiography suite or catheterization lab to tailor device function and/or assess for complications.

This review is intended to be an introductory understanding of device design, physiology, and general troubleshooting for LVADs (pulsatile‐flow and continuous‐flow pumps) and the total artificial heart. For more detailed and technical reviews specific to patient and device management, readers are advised to consult the device‐specific instructions for use manuals or device company representatives.

Pulsatile‐Flow Devices

Although most centers are implanting newer continuous‐flow LVADs, understanding the physiology of the older‐generation devices offers an opportunity to appreciate the advances leading to the current technology. The HeartMate XVE is the only pulsatile‐flow ventricular assist device (VAD) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for destination and bridge‐to‐transplant therapy and will be the model for this article.

The device consists of 2 valved conduits that incorporate the pump in parallel to the native circulation (Figure 1). The titanium pump is generally inserted in a preperitoneal pocket and consists of an electrically driven diaphragm that draws blood into and ejects blood out of a filling chamber.

Figure 1.

Topogram (A) of the HeartMate XVE LVAD. The device is implanted in a preperitoneal or intra‐abdominal pocket. Graphic depiction (B) of the implanted device (reprinted with permission from Thoratec Corporation). Abbreviations: D, driveline; I, inflow cannula; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; O, outflow cannula; P, displacement pump.

During LVAD diastole, the diaphragm is withdrawn, creating a negative intrachamber pressure that draws blood through the inflow cannula from the apex of the left ventricle (LV) into the pumping chamber of the VAD. During LVAD systole, the diaphragm is driven forward and blood is ejected through the outflow cannula into the ascending aorta. The percutaneous driveline consists of an electrical connection to the external controller and a pneumatic conduit that allows atmospheric venting or emergent pneumatic hand pumping.

The HeartMate XVE was evaluated in the Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure (REMATCH) trial, in which 129 patients with late‐stage cardiomyopathy who were not candidates for heart transplantation were randomized to receive either medical therapy or the HeartMate XVE as destination therapy. Although a variety of LVADs have previously been effectively used to bridge critically ill patients, this was the first study to evaluate the efficacy of long‐term therapy in a high‐risk (non–transplant eligible) population. Patients who were alive on LVAD therapy had significant improvements in HF symptoms (New York Heart Association class II vs IV), mood, exercise capacity, and survival (1‐year survival 52% vs 25%; median survival 408 days vs 150 days).2

The cumbersome pump size and wear and tear of the many interacting components, however, offered opportunity for device failure or pocket infection, ultimately limiting duration of therapy. The leading causes of death for patients randomized to device therapy were sepsis or pump dysfunction, with an expected mechanical pump replacement rate of 63% by 2 years in surviving patients.2., 3.

Continuous‐Flow Devices

Continuous‐flow LVADs, or so‐called second‐ and third‐generation LVADs, have been engineered to overcome some of the mechanical limitations of their pulsatile‐flow predecessors. Newer‐generation LVADs are engineered to minimize the interaction of moving parts, which has significantly prolonged pump durability. The smaller design of continuous‐flow devices has also extended LVAD therapy to smaller individuals (notably women and children). It has also been associated with decreased perioperative morbidity during implantation.

Continuous‐flow pumps are classified as axial or centrifugal flow based on the design of the impeller. Axial‐flow devices include the HeartMate II (Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA), Jarvik 2000 (Jarvik Heart, New York, NY), and DeBakey (MicroMed, Houston, TX). These utilize a turbine or corkscrew design to propel blood in a path parallel to the impeller into the outflow cannula. Centrifugal devices, including the VentrAssist (Ventracor, Sydney, Australia), HeartWare (HeartWare, Framingham, MA), Levacor (WorldHeart, Salt Lake City, UT), and HeartMate III (Thoratec), use a spinning rotor to draw blood in along the rotor's axis and then propel it tangentially through an outflow cannula aligned perpendicular to the inflow cannula.

Currently the HeartMate II is the only FDA‐approved LVAD for bridge‐to‐transplantation and destination therapy. The HeartMate II was effective in clinical trials (6‐month survival 75%, 12‐month survival 68%) and a real‐world registry (18‐month survival 79%) for bridging clinically declining HF patients to heart transplantation and was associated with less‐frequent device failure and fewer infections than its predecessor.4., 5. In the HeartMate II destination therapy trial, 200 late‐stage HF patients were randomized (2:1) to receive either a HeartMate II or HeartMate XVE for MCS without the intention of undergoing heart transplantation. Patients who received the HeartMate II had improved survival (2‐year survival 46% vs 11%), fewer pump failures, and no pump‐pocket infections. Patients in both treatment groups exhibited similar improvement in functional capacity and quality of life. Additionally, 30% of patients initially randomized to the HeartMate XVE eventually had the device exchanged for a HeartMate II.6

Like the HeartMate XVE, the HeartMate II is connected to the native circulation in a parallel manner. The inflow cannula is inserted in the apex and the outflow cannula is placed in the ascending aorta above the coronary arteries (Figure 2). Because the VAD is nonpulsatile, it does not require valves to regulate blood flow (eliminating the common complication of structural valve degeneration that limited the durability of the HeartMate XVE).

Figure 2.

Topogram (A) of the HeartMate II LVAD. The device is implanted in a preperitoneal pocket. Graphic depiction (B) of the implanted device (reprinted with permission from Thoratec Corporation). Abbreviations: D, driveline; I, inflow cannula; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; O, outflow cannula; P, impeller pump.

The titanium pump is an impeller aligned in a magnetically driven motor that can generate up to 10 L/minute of flow. The flow through the HeartMate II and other continuous‐flow LVADs is determined by: (1) the speed of the pump, and (2) the differential pressure between the LV cavity and the aorta. The speed on the HeartMate II may be adjusted to between 6000 and 15 000 rpm and LVAD flow varies directly with the speed setting. The differential pressure is simply the difference in blood pressure between the aorta and LV cavity, assuming there is minimal pressure loss in the cannula (no obstruction). This pressure difference varies inversely with pump flow. In other words, decreasing afterload or increasing preload will increase flow through the LVAD. Because preload to the LVAD (determined by LV intracavitary pressure) varies throughout the cardiac cycle, physical examination will reveal oscillations in the pitch of the LVAD motor on precordial auscultation.7 Because flow thorough the LVAD occurs during diastole, most patients have a markedly decreased pulse pressure and nonpalpable peripheral pulse.

LVAD‐Related Complications

The following section is intended to provide a general overview of LVAD‐related complications. For a detailed and technical review on device parameters, function, and troubleshooting, the clinician is referred to the HeartMate II instructions for use published by Thoratec and a recently published user's guide from the HeartMate II Clinical Investigators.8

Cannula Obstruction

Transient obstruction of the inflow cannula by the LV myocardium, colloquially labeled “suck‐down,” can occur when the preload to the LV is inadequate, the LV cavity is overly decompressed (LVAD speed too high), or the inflow cannula is malpositioned. If the VAD speed is too high or there is inadequate preload, the LV cavity on echocardiography will appear small and crowded, the interventricular septum will bow toward the LV, and the aortic valve may fail to open.

If frequent suction events are occurring secondary to a malpositioned inflow cannula, the ventricular cavity will be inadequately unloaded and the patient may have clinical evidence of poor perfusion and congestive HF; surgical repositioning or device replacement may be required. Irritation of the myocardial wall may cause ventricular arrhythmias. Fixed obstruction to flow through the VAD circuit can occur from kinks in the cannula, pannus, or entrapment of the inflow cannula in the native LV myocardium. Obstruction of VAD flow should be suspected in patients with new or persistent symptoms of congestion and decreased pump flow on the LVAD display. If the patient should develop thrombus within the pump itself, the clinician will observe symptoms of congestive HF and increased power on the LVAD display. Echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), or fluoroscopy and selective angiography are helpful for identifying cannula obstruction, entrapment, and distortion.9., 10., 11.

LVAD‐related hemodynamic problems that clinicians should be cognizant of are summarized in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Potential causes of (A) suction events and (B) inadequate left ventricular unloading with a continuous‐flow LVAD. Abbreviations: AV, atrioventricular; CVP, central venous pressure; LV, left ventricular; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; OR, operating room; RV, right ventricular; RVAD, right ventricular assist device.

Figure 4.

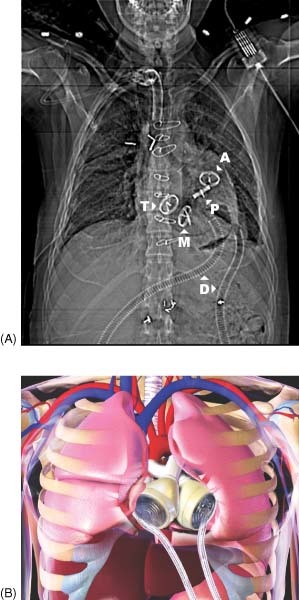

Topogram (A) of the CardioWest total artificial heart. The device replaces the native ventricles and cardiac valves. Four tilting disk valves are located in the tricuspid, mitral, pulmonic, and aortic positions. Graphic depiction (B) of the implanted device (courtesy of SynCardia Systems). Abbreviations: A, aortic; D, driveline; M, mitral; P, pulmonic; T, tricuspid.

Right‐Ventricular Failure

Right‐ventricular (RV) function is one of the primary determinants of effective LVAD therapy. If the RV cannot provide the LVAD with an adequate reservoir of blood, the pump has nothing to eject and the output will decrease. In fact, preoperative RV dysfunction as evidenced by hemodynamics (decreased RV stroke work index, increased RA pressure, decreased PA pressures), echocardiography (RV geometry, tricuspid annular velocity), and liver congestion portend a poor prognosis after LVAD implantation.12., 13., 14., 15. Females and patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathies are more likely to have RV dysfunction.14

Arrhythmias

With an LVAD in place, the LV generally tolerates rhythm disturbance; however, RV function may become compromised. Whereas mechanical unloading of the heart reduces the proclivity for arrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias arise from ischemic substrate, scar tissue, or irritation of the myocardium by the inflow cannula.16., 17. Often the tissue around the cannula itself is substrate, which can perpetuate ventricular tachycardia.18 Efforts to reduce ventricular arrhythmias and maintain atrioventricular synchrony will improve the LVAD's efficacy. Clinically significant ventricular or atrial arrhythmias should treated with antiarrhythmic medications, pacing, or ablation.

Aortic Valve Disease

Aortic valve structure and function should be closely scrutinized before and after LVAD implantation. Allowing for periodic opening of the aortic valve may prevent commissural fusion and stasis of blood.19., 20. For continuous‐flow devices, this entails decreasing the pump speeds under echocardiographic guidance and visualization of valve excursion.

Aortic regurgitation can occur secondary to leaflet remodeling from exposure to high LVAD flows in the ascending aorta. Significant lesions result in recirculation of blood flow rather than delivery of LVAD output to the systemic circulation. Echocardiography is an effective way for identifying regurgitation and the associated inadequate decompression of the LV. Symptomatic lesions may require surgical correction.

Bleeding and Thrombosis

Inflammatory, procoagulant, and fibrinolytic processes ensue once the foreign surface of the LVAD is introduced into a patient.21 Thrombosis and bleeding, even unrelated to surgery, are familiar complications. Thrombus in the VAD itself can cause pump failure, and clots on the cannula can obstruct LVAD flow or embolize peripherally.

From the clinical trials, the anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies for the HeartMate II included 81 mg of aspirin and a vitamin K antagonist with an international normalized ratio goal ranging from 2.0 to 3.5. Some centers in the trial also used 75 mg of dipyridamole (3 times daily). More recent data suggest that the international normalized ratio goals could safely be lowered (to 1.5 to 2.5) to minimize hemorrhagic complications without additional risk of thrombosis.22 Some centers use platelet‐function studies or thromboelastography to titrate antiplatelet agents, although published data for guiding therapy are scarce.

Bleeding complications ranging from epistaxis to intracranial hemorrhage have been observed in LVAD patients. Compared with pulsatile LVADs, patients with continuous‐flow devices have notably higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding.23 Shear stress from the impeller of the LVAD impairs platelet aggregation and can cause an acquired von Willebrand's syndrome.24., 25., 26. Additionally, it is hypothesized that the decreased pulse pressure promotes arteriovenous malformations.27 With any type of bleeding, adjustment or interruption of antithrombotic medications is usually necessary. Promoting pulsatility by decreasing the LVAD speed may reduce bleeding from arteriovenous malformations.

Infection

Clinical evaluation of patients with implantable devices should always include a thorough screen for infections. Vigilant surveillance and wound care of the driveline site are imperative for successful long‐term therapy. For driveline erythema/discharge, fevers or leukocytosis, blood and driveline wound cultures should be obtained. Positive cultures should be treated with directed antibiotic therapy and guidance from an infectious disease specialist. Persistent symptoms warrant further imaging with CT of the chest and abdomen to evaluate for driveline or device abscess or fluid collections. Therapy may include a long‐term suppressive antibiotic, wound debridement, or device removal.

Total Artificial Heart

Patients with evidence of severe RV compromise may be poor candidates for isolated LV mechanical support. Considering that outcomes with RVAD implantation are suboptimal and that no long‐term implantable RVAD is currently available, an alternative to biventricular VAD support is the total artificial heart (TAH). The CardioWest temporary Total Artificial Heart is the only TAH approved by the FDA as a bridge to transplantation. Copeland and colleagues have reported a 79% success rate of bridging patients to transplantation, with post‐transplant survival similar to the United Network for Organ Sharing registry.28

The TAH consists of 2 pneumatically driven pumps with tilting disk valves and short outflow grafts that replace both native ventricles, the proximal segment of the aorta and pulmonary artery, and all 4 of the associated valves (Figure 5). Thus, complications related to native valve disease, rhythm disturbances, and RV dysfunction are eliminated. Other than significant RV failure, myocardial‐wall rupture, fulminant cardiac rejection, and refractory arrhythmias are possible conditions that would prevent LVAD implantation or optimal VAD function, and patients with these conditions could be considered for the TAH.

Figure 5.

Intraoperative photograph of total artificial heart implantation. The total artificial heart seen in situ, prior to chest closure.

The CardioWest TAH requires that adequate thoracic cavity space be available for implantation, thus the patient must have a body surface area of 1.7 m2 and/or anterior‐posterior diameter of ≥10 cm on thoracic CT. The pneumatic drivelines for each ventricle exit from the left upper abdomen and connect to the driver.

Each pump has a capacity of 70 mL and the system can generate up to 9.5 L/minute of output. The stroke volume of each pump is not directly measured but calculated from the amount of air displaced from the pump during the filling phase. Adjustable parameters to optimize stroke volume are: (1) vacuum pressure to withdraw the diaphragm in diastole, (2) ejection rate, (3) the relative timing of systole to diastole, and (4) the individual ejection pressures for each pump. The pump rate and vacuum pressure should be adjusted to allow for partial filling and the ejection pressure should be set to ensure complete ejection (goal stroke volume of 50 to 60 mL).

Device alarms are related to low flow, low power, increased pressure, and asynchronous output from both ventricles. Thorough clinical evaluation for alarms should include evaluation of atrial tamponade, hypovolemia/ bleeding, outflow‐cannula obstruction, and driveline kink.

After TAH implantation, there is no need for inotropes or antiarrhythmic therapy, as the myocardium has been removed. The currently available drivers require that the patient remain in the hospital after implantation; however, a portable take‐home driver is being offered for stable patients enrolled in an ongoing clinical trial. The TAH is approved for bridge to transplantation and the device is not intended for patients who are not candidates for heart transplantation.

Conclusion

The population of patients with end‐stage HF continues to expand. Implantable MCS devices have demonstrated an ability to improve patient survival and quality of life in this sick cohort of patients. Indications for MCS have expanded beyond acute rescue and bridge to transplantation to now also include long‐term (destination) therapy. Continuing technological advances have created an increasing number of VADs. Patients are regularly being discharged to home with mechanical support, and outside providers who may be taking care of these patients should be acquainted with general device function and management.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Sharif Ewees (28 Media, Richmond, VA) for his help with the figures and graphics. Dr. Vigneshwar Kasirajan and Dr. Michael L. Hess receive consulting honorarium from Syncardia.

References

- 1. Taylor DO, Stehlik J, Edwards LB, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty‐sixth Official Adult Heart Transplant Report—2009. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1007–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long‐term use of a mechanical left ventricular assist device for end‐stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dembitsky WP, Tector AJ, Park S, et al. Left ventricular assist device performance with long‐term circulatory support: lessons from the REMATCH trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:2123–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous‐flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pagani FD, Miller LW, Russell SD, et al. Extended mechanical circulatory support with a continuous‐flow rotary left ventricular assist device. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous‐flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2241–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khalil HA, Cohn WE, Metcalfe RW, et al. Preload sensitivity of the Jarvik 2000 and HeartMate II left ventricular assist devices. ASAIO J. 2008;54:245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, et al. Clinical management of continuous‐flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(4 suppl): S1–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horton SC, Khodaverdian R, Chatelain P, et al. Left ventricular assist device malfunction: an approach to diagnosis by echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1435–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park MH, Goudreau E, Tolman DE, et al. Fluoroscopy and selective angiography of left ventricular assist system inflow cannula as a method of detecting cannula entrapment. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;44:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raman SV, Sahu A, Merchant AZ, et al. Noninvasive assessment of left ventricular assist devices with cardiovascular computed tomography and impact on management. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Puwanant S, Hamilton KK, Klodell CT, et al. Tricuspid annular motion as a predictor of severe right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Potapov EV, Stepanenko A, Dandel M, et al. Tricuspid incompetence and geometry of the right ventricle as predictors of right ventricular function after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1275–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ochiai Y, McCarthy PM, Smedira NG, et al. Predictors of severe right ventricular failure after implantable left ventricular assist device insertion: analysis of 245 patients. Circulation. 2002;106(12 suppl 1): I198–I202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lietz K, Long JW, Kfoury AG, et al. Outcomes of left ventricular assist device implantation as destination therapy in the post‐REMATCH era: implications for patient selection. Circulation. 2007;116:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bedi M, Kormos R, Winowich S, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias during left ventricular assist device support. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1151–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andersen M, Videbaek R, Boesgaard S, et al. Incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in patients on long‐term support with a continuous‐flow assist device (HeartMate II). J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:733–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ziv O, Dizon J, Thosani A, et al. Effects of left ventricular assist device therapy on ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1428–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose AG, Park SJ, Bank AJ, et al. Partial aortic valve fusion induced by left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mudd JO, Cuda JD, Halushka M, et al. Fusion of aortic valve commissures in patients supported by a continuous axial flow left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27: 1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spanier T, Oz M, Levin H, et al. Activation of coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:1090–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyle AJ, Russell SD, Teuteberg JJ, et al. Low thromboembolism and pump thrombosis with the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device: analysis of outpatient anti‐coagulation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crow S, John R, Boyle A, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding rates in recipients of nonpulsatile and pulsatile left ventricular assist devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malehsa D, Meyer AL, Bara C, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome after exchange of the HeartMate XVE to the HeartMate II ventricular assist device. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:1091–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steinlechner B, Dworschak M, Birkenberg B, et al. Platelet dysfunction in outpatients with left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klovaite J, Gustafsson F, Mortensen SA, et al. Severely impaired von Willebrand factor–dependent platelet aggregation in patients with a continuous‐flow left ventricular assist device (HeartMate II). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2162–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Letsou GV, Shah N, Gregoric ID, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding from arteriovenous malformations in patients supported by the Jarvik 2000 axial‐flow left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Copeland JG, Smith RG, Arabia FA, et al. Cardiac replacement with a total artificial heart as a bridge to transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]