Abstract

Antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy may be beneficial for patients with symptoms attributable to atrial fibrillation despite adequate rate control. The limited long‐term efficacy of AAD and the relatively large proportion of patients discontinuing therapy because of side effects led to the development of nonpharmacological therapies to achieve rhythm control. Pressing questions remain about the effect of ablation therapy on long‐term patient outcomes. Based on recent clinical trials and meta‐analyses, ablation appears more effective and possibly safer than AAD for long‐term maintenance of sinus rhythm in selected patients, but the evidence is insufficient to recommend ablation in preference to drug therapy as the first AAD therapy for the majority of patients in whom a rhythm control strategy is justified. Herein, we review the most current evidence supporting the use of AAD and catheter ablation in atrial fibrillation. Copyright © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Hugh Calkins, MD is a consultant to Sanofi Aventis, Biosense Webster, and Medtronic, and he receives research support from Biosense Webster and Medtronic. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

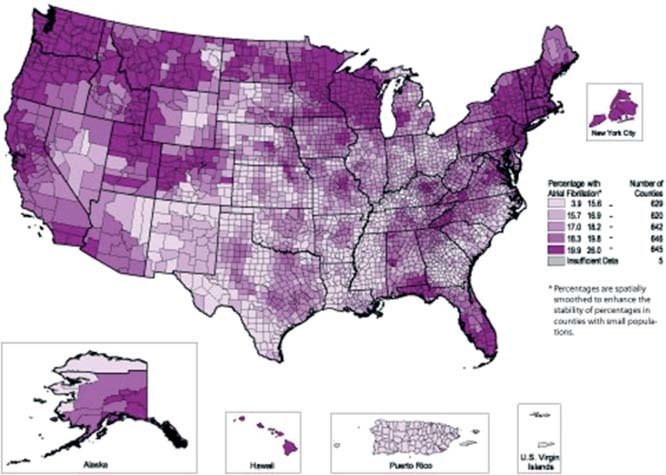

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, increasing in prevalence with age and associated with considerable morbidity and cost (Figure 1).1, 2 Classification of AF as paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent is a basis for comparative assessment of treatment strategies. Paroxysmal AF is intermittent and self‐terminating in < 7 days. Persistent AF lasts longer but may be terminated by pharmacological or electrical cardioversion. Permanent AF implies either that cardioversion has failed or that the patient and physician have decided to allow AF to continue without further efforts to restore sinus rhythm. Optimally, decisions about treatment of patients with AF are determined by the frequency and severity of symptoms and by the impact of the arrhythmia on prognosis.

Figure 1.

Stroke hospitalizations of Medicare beneficiaries with atrial fibrillation, 1995–2002.

Current therapy for AF involves interventions directed at ventricular rate control using atrioventricular nodal blockade and appropriate antithrombotic therapy to prevent ischemic stroke and systemic embolism.3 The use of these measures is based on evidence from several large randomized trials that found no significant improvement in clinical outcomes with efforts to maintain sinus rhythm through antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy compared with rate control and sustained anticoagulation.4, 5 Antiarrhythmic drug therapy may be beneficial, however, for patients with symptoms attributable to AF despite adequate rate control. On average, AAD therapy successfully maintains sinus rhythm in no more than 50% of patients after 1 year.4 The limited long‐term efficacy of AAD and the relatively large proportion of patients discontinuing therapy because of side effects are among the reasons that nonpharmacological therapies have been developed to achieve rhythm control.

In selected patients, catheter ablation seems more effective than AAD therapy in preventing recurrent AF.6, 7, 8 Follow‐up in trials of ablation therapy has rarely extended beyond 1 year, however, leaving open questions about long‐term safety and efficacy. The majority of patients with AF are aged > 70 years, but older patients have not been included in most ablation trials. No trial has systematically compared mortality, stroke, or hospitalization in patients undergoing AF ablation with those managed using a strategy of rate control and anticoagulation, which has not been found superior to rhythm control, and focused on the surrogate endpoint of maintenance of sinus rhythm. Ablation was associated with improved quality of life in some studies, but effects on other endpoints are less well established and complications of ablation must be considered in assessing the relative risks and benefits of the procedure.9 These concerns, as well as economic considerations, stand in the way of accepting catheter ablation as a first‐line therapy for a broad segment of the population with AF.

Although the guidelines of the Heart Rhythm Society/ European Heart Rhythm Association/European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society for management of patients with AF classify ablation as a class IIa treatment strategy, and this technique is frequently employed, pressing questions remain about the effect of ablation therapy on patient outcomes.

Antiarrhythmic Drugs for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

Antiarrhythmic drugs are widely used for treatment of patients with AF, despite limited efficacy and frequent adverse effects.10, 11 Although in clinical trials, AAD therapy did not reduce mortality, stroke, or heart failure compared with rate‐control therapy, some patients require AAD therapy to control symptoms associated with AF (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Trial Comparing Efficacy of Ablation and Antiarrhythmic Drugs for the Treatment of AF

| Study | N (Ablation/ AAD) | AF Type | Efficacy Rate for Ablation | Efficacy Rate for AAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krittayaphong et al | 15/15 | Persistent AF | 78.65% | 40% |

| Waznie et al | 33/37 | PAF, 4% persistent | 85% | 21% |

| Pappone et al | 99/99 | PAF | 85% | 35% |

| Oral et al | 77/69 | Persistent | 74% | 58% |

| Stabile et al | 68/69 | PAF, 33% persistent | 65.9% | 8.7% |

| Jaïs et al | 53/59 | PAF | 89% | 23% |

| Forleo et al | 35/35 | Persistent AF, 41% PAF | 80% | 42.9% |

Abbreviations: AAD, antiarrhythmic drug therapy; AF, atrial fibrillation; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

Amiodarone is more effective than other AADs in maintaining sinus rhythm in patients with AF.10, 11, 12 Also, it is one of the few AADs not associated with increased mortality in patients with heart failure.3, 13 It has little negative inotropic effect and a low potential for proarrhythmic toxicity. Use of amiodarone is limited mostly by its extensive side‐effect profile, including hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, pulmonary and hepatic toxicity, and dermatological, neurological, and ophthalmic reactions.14

Dronedarone was developed to overcome the negative attributes of amiodarone and proved to be effective in the Dronedarone Atrial Fibrillation Study After Electrical Cardioversion (DAFNE) trial.15 Subsequently, 2 multicenter, double‐blind, randomized trials, the American‐Australian Trial With Dronedarone in Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter Patients for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm (ADONIS) and the European Trial in Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter Patients Receiving Dronedarone for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm (EURIDIS), assessed the efficacy of dronedarone, 400 mg twice daily, in patients with recurrent AF after cardioversion.16 In both trials, treatment with dronedarone significantly delayed recurrence of AF compared with placebo with no major side effects.17 Dronedarone also decreases the ventricular rate in patients who relapsed into AF, and this was confirmed in the Efficacy and Safety of Dronedarone for the Control of Ventricular Rate During Atrial Fibrillation (ERATO) trial.18 Patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure should not use dronedarone, based on the findings of the Antiarrhythmic Trial With Dronedarone in Moderate to Severe Chronic Heart Failure Evaluating Morbidity Decrease (ANDROMEDA) study.19, 20

The primary endpoint of the A Placebo‐Controlled, Double‐Blind, Parallel‐Arm Trial to Assess the Efficacy of Dronedarone 400 mg BID for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Hospitalization or Death From Any Cause in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation/Atrial Flutter (ATHENA) trial was the composite of hospitalization due to cardiovascular events or death in patients with AF.21 The 4628 participants had either paroxysmal or persistent AF or atrial flutter. After a mean follow‐up of 21 months, patients in the dronedarone group had significantly fewer primary events. Combined with the primary endpoint, this yielded a hazard ratio of 0.76 favoring dronedarone; cardiovascular mortality was also lower in the dronedarone group.

The Randomized, Double‐Blind Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Dronedarone (400 mg bid) Versus Amiodarone (600 mg qd for 28 Days, Then 200 mg qd Thereafter) for at Least 6 Months for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm in Patients With AF (DYONISOS)22 compared dronedarone with amiodarone. The primary composite endpoint was time to first recurrence of AF or premature discontinuation of the study drug treatment for intolerance or lack of efficacy. More patients given dronedarone had recurrence of AF or prematurely stopped taking the study drug at 12 months. Taken together, these results support the notion that dronedarone is safer but less efficacious than amiodarone.22

The safety and efficacy of dofetilide, a class III AAD, has been evaluated in several randomized trials involving patients with AF. It has no negative inotropic effect, but QT‐interval prolongation is associated with a risk for torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia. The Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide in Congestive Heart Failure (DIAMOND‐CHF) trial and the Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigation Research on Dofetilide (SAFIRE‐D) trial compared dofetilide with placebo, and although dofetilide decreased hospitalizations and was more effective than placebo, there was no difference in mortality.23, 24 The incidence of torsades de pointes was only 0.8%.

Sotalol, a C β‐blocker with class III effects, has not been useful for pharmacological cardioversion of AF, but can be used to maintain sinus rhythm. Sotalol should be avoided in patients with significant left ventricular hypertrophy or heart failure because of negative inotropic and proarrhythmic effects. Similar to other class III drugs, sotalol prolongs the QT interval and carries a risk for torsades de pointes that is accentuated in patients with impaired renal function and may be more frequent in women than in men.11 Sotalol is less efficacious than amiodarone for the prevention of recurrent AF.4, 10

For patients without structural heart disease who are candidates for rhythm control, the class Ic antiarrhythmic agents, flecainide and propafenone, are recommended as first‐line therapy.3 Flecainide therapy was associated with increased mortality compared with placebo among patients in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial with previous myocardial infarction and ventricular ectopy.25 Based on these data, class Ic drugs are contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease,26 but cardiac side effects developed in 11% of the patients receiving flecainide. Propafenone was assessed in 2 large randomized trials, Rythmol Atrial Fibrillation Trial (RAFT) and European Rythmol/Rythmonorm Atrial Fibrillation Trial (ERAFT),27 the results of which were similar, with propafenone at the highest dose producing up to 70% suppression of recurrent AF, but withdrawal of treatment due to side effects was relatively frequent.

Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation

The disappointing performance of AAD prompted development of catheter‐based strategies for rhythm control in patients with AF.28 Circumferential pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is today the most commonly performed AF ablation procedure, with a high success rate, especially in patients with paroxysmal AF and structurally normal hearts. Ablation for AF is on the rise worldwide; a recent international registry reported > 5000 such procedures, with a success rate of 50%–70%.9 The increasing popularity of this modality and results from the first randomized trials led to the proposal that AF ablation be considered a second‐line therapy in patients with AF who are either intolerant of or fail to respond sufficiently to AAD therapy.3

Thus far, only a few small trials have assessed the efficacy and safety of PVI in patients with AF (Tables 2 and 3). No large trials comparing PVI with both AAD therapy and rate‐control therapy have been performed. It is difficult to compare results across trials because of differences in the ablation techniques employed and the heterogeneity of patient populations enrolled (Table 1).6, 29

Table 2.

Completed Clinical Trials Studying Efficacy Rates of Catheter Ablation for Persistent AF

| Study | N | Follow‐Up (mo) | Concomitant AAD (%) | Efficacy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O'Neill et al | 153 | 34 | 13 | 89 |

| Della Bella et al | 83 | 14 ± 12 | 61 | 69 |

| Nademanee et al | 381 | 28 | 71 | 85 |

| Neuman et al | 53 | 12 | 0 | 42 |

| Elayi et al | 47/48/49 | 16/14 | NA | 28/83/94 |

| Arentz et al | 43 | 15 ± 4 | 0 | 40/61 |

| Verma et al | 80 | 12 | 0 | 78/82 |

| Seow et al | 53 | 21.6 ± 8.8 | 0 | 62.5 |

| Oral et al | 100 | 13 ± 7 | 0 | 57 |

| Willems et al | 62 | 16 | 0 | 20/69 |

| Oral et al | 77 | 12 | 0 | 74 |

| Lim et al | 51 | 17 ± 9 | 17 | 45 |

| Calo et al | 80 | 14 ± 5 | 50 | 61/85 |

| Oral et al | 80 | 9 ± 4 | 0 | 72/75 |

| Haïssaguerre et al | 60 | 11 ± 6 | 12 | 95 |

| Fassini et al | 61 | 12 | 50 | 36/74 |

| Cappato et al | 1619 | 12 | 0/yes | 66/90 |

| 24 | 43/70 |

Abbreviations: AAD, antiarrhythmic drug therapy; AF, atrial fibrillation; NA, not applicable.

Table 3.

Completed Clinical Trials Studying Efficacy Rates of Catheter Ablation for Paroxysmal AF

| Study | N | Follow‐Up (mo) | Concomitant AAD (%) | Efficacy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Della Bella et al | 207 | 14 ± 12 | 0.58 | 88 |

| Van Belle et al | 141 | 15 ± 8 | None | 59 |

| Jaïs et al | 53 | 12 | None | 89 |

| Nademanee et al | 254 | 27.6 | 13 | 89 |

| Wang et al | 106 | 12 | 0.05 | 93/94 |

| Fiala et al | 110 | 48 ± 8 | None | 80 |

| Dixit et al | 77 | 12 | None | 65 |

| Arentz et al | 67 | 15 ± 4 | None | 54/72 |

| Chang et al | 88 | 12 ± 6 | Yes | 45/82 |

| Verma et al | 120 | 12 | None | 85/87 |

| Sheikh et al | 100 | 9 | Yes | 82/90 |

| Jaïs et al | 74 | 18 ± 4 | None | 91 |

| Hocini et al | 90 | 15 ± 4 | None | 69/87 |

| Fassini et al | 126 | 12 | 50 | 62/76 |

| Oral et al | 100 | 6 | None | 67/85 |

| Oral et al | 80 | 6 | None | 36/74 |

Abbreviations: AAD, antiarrhythmic drug therapy; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Catheter ablation appeared superior to AAD therapy in the multicenter Catheter Ablation Versus Antiarrhythmic Drugs for Atrial Fibrillation (A4) study.7 The trial, limited to 4 centers, enrolled 112 patients with recurrent AF after treatment with ≥ 1 AAD. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients free of recurrent AF between months 3 and 12. A total of 53 patients randomized to ablation underwent an average of 1.8 ± 0.8 procedures. A higher proportion of patients in the ablation group was free of AF after 1 year than in those assigned to AAD (89% vs 23%). The symptoms, exercise capacity, and quality of life were significantly improved with ablation.

Rhythm control can be especially difficult to achieve in patients with longstanding, persistent AF. A recent multicenter trial addressed ablation for patients with AF for > 6 years and persistent AF for > 2 years, on average.30 Patients were randomized to 1 of 3 different treatment strategies: (1) circumferential PVI, (2) pulmonary vein antrum isolation, and (3) a hybrid strategy combining ablation of complex fractionated atrial electrograms followed by PV antrum isolation. The hybrid procedure was associated with the highest likelihood of maintaining sinus rhythm. At 1 year, 61% of patients assigned to hybrid therapy were free of AF without AAD therapy, compared with 11% in the circumferential PV ablation group and 40% in the group treated with isolation of the PV antrum. A second ablation procedure increased success rates to 80%, 56%, and 17%, respectively.

Comparison of Ablation With AAD

Direct comparisons of ablation to AAD therapy are complex because of variations in patient populations, procedure types and outcome measures, and the absence of large randomized trial cohorts (Table 1). Insights derive from 1 relatively large observational study,6 3 meta‐analyses,31, 32, 33 and several smaller randomized trials.29, 34, 35, 36 The observational study included 1171 consecutive patients treated by either complete PVI or medical therapy for AF.6 At a median follow‐up of 2.5 years, AF recurred in fewer ablated than medically treated patients. Ablation was associated with fewer cardiovascular deaths, episodes of heart failure, and ischemic cerebrovascular events, and with improvement in quality of life. Similar findings were noted in 4 randomized trials comparing ablation with AAD therapy in patients with newly diagnosed AF,29 paroxysmal AF,29, 34 and persistent AF,36 although each had notable limitations.

An international survey of catheter ablation for AF at 181 electrophysiology laboratories reported a major complication rate of 6%.37 Included in this figure was a nearly 1% incidence of stroke or transient ischemic attack and a 1.2% incidence of cardiac tamponade. In this analysis, PVI was associated with a 3% rate of major complications and a stroke rate of 1%. This lower complication rate probably reflects the expertise at the centers involved and continued evolution of procedural safety. A 3% major complication rate, though not negligible, is comparable to that observed with high‐risk percutaneous coronary intervention.38 On the other hand, AAD therapy carries the risk of proarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nearly 1 in 4 patients randomly assigned to medical therapy in this analysis had an adverse event related to treatment.

More recently, the THERMOCOOL (Biosense Webster, a Johnson & Johnson Company, Waterloo, Belgium) Catheter Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Trial,8 a multicenter randomized clinical trial, studied paroxysmal AF patients who failed ≥ 1 AAD and who had experienced ≥3 symptomatic AF episodes in the prior 6 months. Thirty‐five percent of patients were previously treated with sotalol and approximately half with propafenone, whereas very few patients in both treatment arms were treated with amiodarone, just 7% in the catheter‐ablation arm and 10% in the AAD therapy arm. Patients were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to radiofrequency catheter ablation or to an AAD other than one they failed. After 9 months, 66% of patients in the ablation arm and 16% of patients in the drug‐treatment arm remained free from protocol‐defined treatment failure, a significant difference in the primary endpoint. The researchers report that ablation was associated with the elimination of symptomatic atrial arrhythmia in 70% of patients and the elimination of any atrial arrhythmia in 63% of patients at 1 year. Importantly, in this multicenter trial involving 19 centers, there were no serious complications. Quality‐of‐life scores significantly improved in patients treated with ablation compared with those treated with further AAD therapy.8

The Catheter Ablation Versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation (CABANA) trial presented at the last American College of Cardiology meeting addressed more challenging cases, roughly two‐thirds having persistent or longstanding paroxysmal AF. Enrolled individuals had considerable comorbidity, including coronary disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Although the primary endpoint was freedom from AF, the study was designed to assess mortality and stroke following ablation. In the pilot study, 60 patients were followed for 9 months beyond a 3‐month blanking period during which postprocedural outcomes were not enumerated. By the end of the study, 65% of patients treated by catheter ablation were free of symptomatic AF compared with 41% treated with AAD, a 58% reduction in relative risk. There was no significant difference in the proportion of participants free of recurrent AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia following ablation compared with AAD. Still enrolling participants, the CABANA trial intends to include up to 3000 patients followed for 5 years.

Conclusions and Future Directions

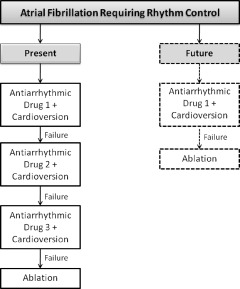

Based on the scientific evidence reviewed above, the guidelines of the Heart Rhythm Society/European Heart Rhythm Association/European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society assign a class IIa recommendation to catheter ablation as an alternative to AAD for prevention of recurrent AF in symptomatic patients with little to no left‐atrial enlargement.39 Ablation appears more effective and possibly safer than AAD therapy for long‐term maintenance of sinus rhythm in selected patients, but the evidence is insufficient to recommend ablation over AAD therapy as the preferred primary antiarrhythmic treatment strategy for most patients when rhythm control is justified. At present, several failed attempts of cardioversion enhanced with AAD are attempted before recommending catheter ablation (Figure 2). In the future, it is possible that catheter ablation will either be first‐line therapy or it will be proposed after the first sign of failed medical therapy for rhythm control. Larger randomized trials are needed to compare the long‐term safety and efficacy of these treatments coupled with comprehensive cost‐effectiveness analyses. The CABANA trial may provide critically important long‐term follow‐up data, including such important outcomes as stroke and all‐cause mortality.

Figure 2.

Present and future of catheter ablation in the management of patients with atrial fibrillation requiring rhythm control.

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting the use of ablation for treatment of AF, critical questions and limitations remain. Trial results cannot be generalized to the majority of patients with AF, considering that most are older and many have permanent AF, conditions that have been under‐represented in trials carried out to date. Does ablation reduce the mortality and morbidity due to stroke and heart failure in patients with AF? Under what circumstances should ablation be considered a first‐line therapy for patients with AF?

If proven safe and effective in long‐term studies, catheter ablation may replace pharmacological therapy for rhythm control. The goal is to simplify ablation techniques to make them less operator‐dependent and applicable to a wider proportion of patients with symptomatic AF.

References

- 1. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285: 2370–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257–e354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1834–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pappone C, Rosanio S, Augello G, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and quality of life after circumferential pulmonary vein ablation for atrial fibrillation: outcomes from a controlled nonrandomized long‐term study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jaïs P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, et al. Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study [published correction appears in Circulation. 2009;120:e83]. Circulation. 2008;118:2498–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, et al. Worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:1100–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roy D, Talajic M, Dorian P, et al. Amiodarone to prevent recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Canadian Trial of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:913–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh BN, Singh SN, Reda DJ, et al; Sotalol Amiodarone Atrial Fibrillation Efficacy Trial (SAFE‐T) Investigators. Amiodarone versus sotalol for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352: 1861–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shinagawa K, Shiroshita‐Takeshita A, Schram G, et al. Effects of antiarrhythmic drugs on fibrillation in the remodeled atrium: insights into the mechanism of the superior efficacy of amiodarone. Circulation. 2003;107:1440–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG, et al. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia: Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zimetbaum P. Amiodarone for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Touboul P, Brugada J, Capucci A, et al. Dronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a dose‐ranging study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1481–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh BN, Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, et al. Dronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:987–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tschuppert Y, Buclin T, Rothuizen LE, et al. Effect of dronedarone on renal function in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:785–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davy JM, Herold M, Hoglund C, et al. Dronedarone for the control of ventricular rate in permanent atrial fibrillation: The Efficacy and safety of dRonedArone for The cOntrol of ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation (ERATO) study Am Heart J. 2008;156:527e1–527e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Køber L, Torp‐Pedersen C, McMurray JJ, et al. Increased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failure [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1384]. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2678–2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laughlin JC, Kowey PR. Dronedarone: a new treatment for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1220–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van Eickels M, et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2487]. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Le Heuzey JY, De Ferrari GM, Radzik D, et al. A short‐term, randomized, double‐blind, parallel‐group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dronedarone versus amiodarone in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: the DIONYSOS study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Torp‐Pedersen C, Møller M, Bloch‐Thomsen PE, et al. Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341: 857–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pedersen OD, Bagger H, Keller N, et al. Efficacy of dofetilide in the treatment of atrial fibrillation‐flutter in patients with reduced left ventricular function: a Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide (DIAMOND) substudy. Circulation. 2001;104:292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med. 1991;324: 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson JL, Gilbert EM, Alpert BL, et al ; Flecainide Supraventricular Tachycardia Study Group. Prevention of symptomatic recurrences of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients initially tolerating antiarrhythmic therapy: a multicenter, double‐blind, crossover study of flecainide and placebo with transtelephonic monitoring. Circulation. 1989;80:1557–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meinertz T, Lip GY, Lombardi F, et al. Efficacy and safety of propafenone sustained release in the prophylaxis of symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (The European Rythmol/Rythmonorm Atrial Fibrillation Trial [ERAFT] Study). Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1300–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wazni OM, Marrouche NF, Martin DO, et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first‐line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293: 2634–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elayi CS, Verma A, Di Biase L, et al. Ablation for longstanding permanent atrial fibrillation: results from a randomized study comparing three different strategies. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5: 1658–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Noheria A, Kumar A, Wylie JV Jr, et al. Catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Calkins H, Reynolds MR, Spector P, et al. Treatment of atrial fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: two systematic literature reviews and meta‐analyses. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piccini JP, Lopes RD, Kong MH, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pappone C, Augello G, Sala S, et al. A randomized trial of circumferential pulmonary vein ablation versus antiarrhythmic drug therapy in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the APAF Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2340–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stabile G, Bertaglia E, Senatore G, et al. Catheter ablation treatment in patients with drug‐refractory atrial fibrillation: a prospective, multi‐centre, randomized, controlled study (Catheter Ablation for the Cure of Atrial Fibrillation Study). Eur Heart J. 2006;27:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oral H, Pappone C, Chugh A, et al. Circumferential pulmonary‐vein ablation for chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, et al. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention—summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Circulation. 2006;113:156–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow‐up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed and approved by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2007;9:335–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]