Abstract

Background:

There are few recent data to delineate the beyond lipids‐decreased effect of statins and the effect of different doses of statins on endothelial‐derived microparticles (EMPs) and circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM).

Hypothesis:

Statins might have the beyond lipids‐decreased effect and there were different effects between different doses of statins on EMPs and circulating EPCs in patients with ICM.

Methods:

One hundred patients with ICM and 100 healthy examined people, who served as the normal control group, were recruited to this study. Patients were randomly divided into 2 groups: 10‐mg atorvastatin group (n = 50) and 40‐mg atorvastatin group (n = 50). All subjects were followed for 1 year. The levels of serum lipids, oxidized low‐density lipoprotein (oxLDL), high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP), circulating EPCs, and EMPs were examined in all subjects. The incidences of adverse reactions in the 2 study groups were determined.

Results:

At the beginning of this study, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 study groups. At the end of this study, the levels of total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein, serum hsCRP, oxLDL, and circulating EMPs were significantly decreased; circulating EPCs were significantly increased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group compared to the 10‐mg atorvastatin group, P < 0.05. The multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that receiving only 40 mg of atorvastatin had a significant effect on the levels of circulating EPCs (β = 0.252,P = 0.014). There were no significant differences in the adverse reactions between the 2 groups.

Conclusions:

Use of 40 mg of atorvastatin might decrease the levels of circulating EMPs and increase the number of circulating EPCs in patients with ICM in comparison with 10 mg of atorvastatin, and the effect might be independent of the decrease of lipids, oxLDL, and hsCRP. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

This study was supported by the Bureau of Health of Guangzhou city (2009‐YB‐186). The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Statins, serving as antiatherosclerosis drugs, can significantly decrease the rates of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and have been extensively administered in secondary prevention of CHD. Despite a growing number of studies that have shown statins could decrease the levels of oxidation and inflammation in arteries in patients with CHD and improve the coronary stenosis, the number of patients with heart failure in the population still increased in the last few decades, and the role of statins in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) is still a matter of debate.

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which are positive for CD34, are considered to originate from hematopoietic stem cells.1, 2, 3, 4 The CD34‐positive leukocytes were shown to make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation.5 Adherent EPCs could be characterized by 1,1′‐dioctadecyl‐3,3,3′,3′‐tetramethylindocarbocyanine‐labeled acetylated low‐density lipoprotein (Di‐acLDL) and fluorescein‐5‐isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (UEA‐I) by uptaking Di‐acLDL and combining UEA‐I. At present, the level of circulating EPCs (cEPCs) not only correlates with cumulative cardiovascular risk6 and vascular function7 but also predicts future cardiovascular events and atherosclerotic disease progression in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).8, 9 Recently, advanced stages of heart failure were shown to be associated with reduced levels of cEPCs.10 One study showed ICM was associated with selective impairment of progenitor cell function in the bone marrow and in the peripheral blood.11

Endothelial cells can release microparticles after inflammatory stimulation, and the presence of increased levels of circulating endothelial‐derived microparticles (cEMPs) has been documented in various pathologic conditions including coronary syndromes, in which they reflect endothelial dysfunction and are associated with a poor clinical outcome.12 At present, the ratio of EMPs to EPCs is regarded as a quantitative and clinically feasible measurement of vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes.13 A previous study demonstrated fluvastatin could decrease EMP release from human coronary artery endothelial cells.14 Currently, stabilizing cellular membranes to decrease the release of EMPs is considered as a target of vascular therapy.15

However, there are few data to delineate the beyond lipids‐decreased effect of statins and the effect of different doses of statins on cEPCs and cEMPs. Thus, this study was designed to investigate the beyond lipids‐decreased effect of statins and the differences of 40 mg vs 10 mg of atorvastatin on cEPCs and cEMPs in patients with ICM.

Methods

Subjects

One hundred ICM patients (72 men, 28 women; age 30–80 years [63.38 ± 9.58]) in the cardiovascular department were enrolled in this study from March 2007 to June 2010. Patients with ICM were required to have angiographic evidence of CAD and to have had a previous myocardial infarction (MI) at least 3 months before inclusion in the study; they also had to have persistent, well‐demarcated regional left ventricle (LV) dysfunction by echocardiography or LV angiography and have a patent infarct‐related artery and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) <50%, with LV end‐diastolic dimension >50 mm. The patients with LVEF <45%, LV end‐diastolic dimension >50 mm, and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III‐IV were enrolled into the study. We excluded the individuals with acute infectious diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, liver diseases, thyroid diseases, autoimmune diseases, acute or chronic heart failure due to cardiovascular diseases other than ICM, stroke, renal failure, and lung diseases and patients whose life expectancy was less than 1 year. All patients were fully informed about the objective of the study, and informed consent was obtained from each patient. The present study protocol was approved by our institute's committee on human research. We recruited 100 healthy examined people, with LVEF >50%, LV end‐diastolic dimension ≤50 mm, and NYHA class I‐II, to serve as the normal control group.

In accordance with the hospitalization order, ICM patients were randomly divided into 2 groups: the group given 10 mg per day of atorvastatin (Pfizer, NewYork, USA) (n = 50) (35 men, 15 women, age 46–80 years [62.60 ± 9.39], 39 patients with coronary stent implanted, 32 patients with hypertension,13 patients with diabetes, 15 patients with family medical history, and 13 patients who were smokers) and the group given 40 mg per day of atorvastatin (n = 50) (37 men, 13 women, age 30–79 years [64.15 ± 9.79], 37 patients with coronary stent implanted, 35 patients with hypertension, 13 patients with diabetes, 11 patients with family medical history, and 12 patients who were smokers). Subjects were administered other drugs according to their own situations. Subjects completed a standardized questionnaire on current and past exposure to candidate vascular risk factors. All the enrolled patients were successfully treated with antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and clopidogrel were used alone or together), anti‐ischemic, statin, antihypertension drugs, hypoglycemic drugs, and so on. Between the 2 groups, there were no significant differences in the administration of these medications.

All subjects were followed for 12 months. There were 3, 2, and 3 patients who withdrew from the 10‐mg atorvastatin group, 40‐mg atorvastatin group, and control group, respectively. The incidences of cardiovascular events in the 10‐mg atorvastatin group and the 40‐mg atorvastatin group were 10.6% (5 of 47) and 6.25% (3 of 48) during follow‐up. There were no significant differences in the rates of cardiovascular events between the 2 study groups.

Laboratory Analysis

Serum samples gained from peripheral venous blood were stored at −80°C. The measurement of plasma oxidized low‐density lipoprotein (oxLDL) (TPI Corporation, Johnson City, TN) content was performed with the sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay method.16 Serum fibrinogen, lipid, uric acid, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP), creatine kinase (CK), and alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured by biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi, 717OA, automatic analyzer; Tokyo, Japan).

Echocardiographic Examination

Two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiography was performed on patients in the left lateral decubitus position using a HPsonos2500 echocardiography (Hewlett Packard, Andover, MA) with a broadband (2.5–3.5 MHz) phased‐array transducer. From parasternal long axis view, left atrial dimension was measured, as reported previously. LV end‐diastolic volume, end‐systolic volume, and LVEF were measured and calculated based on the modified Simpson's rule from apical 2‐ and 4‐chamber views. Transmitral flow velocity signals were recorded from apical 4‐chamber view, and the early (E) and late (A) transmitral flow velocity was measured. The ratio of E/A transmitral flow velocity reflects LV diastolic function.

Examination of cEMPs

Briefly, 10 µL of mouse antihuman PE‐CD31 and FITC‐CD42b monoclonal antibody plus 50 µL of prepared plasma were added to tubes. The control tubes were given mouse antihuman PE‐IgG1 and FITC‐IgG1. The PE‐CD31, FITC‐CD42b monoclonal antibody, PE‐IgG1, and FITC‐ IgG1 were all obtained from Beckman‐Coulter (Fullerton, CA). After 30 minutes in culture, the samples were performed by using an Epics Altra Flow Cytometer (Beckman‐Coulter) operated at medium flow‐rate setting, with log gain on light scatter and fluorescence. Events with 0.2‐ to 1.0‐µm size on FS‐SS graph and CD31+/CD42b− were gated as EMPs. The absolute number of EMPs was enumerated from the appropriate dot plot values.

Examination, Cultivation, and Characterization of cEPCs

Examination of cEPCs:

cEPCs were detected in 2 mL of venous blood obtained from subjects by flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur; BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at the beginning and the end of the study, respectively. Mice IgG1‐FITC and mice anti‐human‐CD34‐FITC were obtained from (San Diego, California, USA). Pharmingen. The percentages of CD34+ cells in 50 000 mononuclear cells were calculated.

Cultivation and Characterization of CEPCs:

Mononuclear cells were isolated by density‐gradient centrifugation (Optima LE ‐80K; Beckman‐Coulter) from 20 mL of peripheral blood, and 4 × 106 mononuclear cells were plated on 24‐well culture dishes coated with human fibronectin and gelatin (Sigma‐Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) in endothelial basal medium (CellSystems, Uppsala Science Park, Sweden) supplemented with endothelial growth medium (Lonza Cologne GmbH, Koeln, Germany). SingleQuots and 20% fetal calf serum. After 14 days in culture, nonadherent cells were removed by thoroughly washing with phosphate‐buffered saline. The CD34+ cells were measured in adherent cells by immunohistochemistry after 2 weeks. To detect the uptake of Di‐acLDL, cells were incubated with Di‐acLDL (2.4 µg/mL) at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and incubated with FITC‐labeled UEA‐I (lectin, 10 µg/mL) (Sigma‐Aldrich) for 1 hour. Dual‐staining cells positive for both lectin and Di‐acLDL were judged as EPCs.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS for Windows (version 11.0; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Data were expressed as  . Measurement data for the 2 study groups were compared by using 2 independent samples test. Measurement data among 3 groups were compared by using univariate analysis of variance. Pearson χ

2 test was applied to compare the differences in sex, family medical history, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and so on between the 2 groups. A multivariate linear regression analysis with stepwise methods was performed to test the interactions between receiving 40‐mg atorvastatin and lipids, oxLDL, and hsCRP on the levels of cEPCs. A 2‐sided probability value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

. Measurement data for the 2 study groups were compared by using 2 independent samples test. Measurement data among 3 groups were compared by using univariate analysis of variance. Pearson χ

2 test was applied to compare the differences in sex, family medical history, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and so on between the 2 groups. A multivariate linear regression analysis with stepwise methods was performed to test the interactions between receiving 40‐mg atorvastatin and lipids, oxLDL, and hsCRP on the levels of cEPCs. A 2‐sided probability value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Subjects Among the 3 Groups

The baseline characteristics of the 3 groups are summarized in Table 1. Subjects did not differ in regard to lipids, oxLDL, hsCRP, cEMPs, cEPCs, CK, ALT, fibrinogen, uric acid, age, sex, family medical history, index weight, number of patients with hypertension, number with diabetes, number ever smoking, drugs, echocardiographic indices, and the rate of stent implanted between the 2 study groups. Two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic indices of the 3 groups at enrollment are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of Subjects Among the 3 Groups ( )

)

| TC, mmol/L | TG, mmol/L | LDL, mmol/L | oxLDL, mmol/L | hsCRP, mg/L | cEMPs, n/µL | cEPCs, % | CK, mmol/L | ALT, mmol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10‐mg group (n = 47) | 4.85 ± 0.29 | 1.75 ± 0.81 | 2.75 ± 0.60 | 2.45 ± 0.99 | 7.25 ± 2.04 | 2020.36 ± 206.94 | 0.047 ± 0.022 | 96.23 ± 22.75 | 30.06 ± 5.98 |

| 40‐mg group (n = 48) | 4.97 ± 1.04 | 1.64 ± 0.65 | 2.75 ± 0.96 | 2.79 ± 1.14 | 8.03 ± 3.34 | 2098.56 ± 223.73 | 0.053 ± 0.021 | 93.88 ± 26.65 | 30.83 ± 5.39 |

| Control group (n = 100) | 4.60 ± 0.82 | 1.51 ± 0.66 | 2.58 ± 0.64 | 1.26 ± 1.01 | 1.13 ± 0.89 | 730.43 ± 276.98 | 0.091 ± 0.022 | 77.47 ± 18.09 | 24.92 ± 4.23 |

| Significance | 0.021 | 0.141 | 0.276 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; cEMPs, circulating endothelial‐derived microparticles; cEPCs, circulating endothelial progenitor cells; CK, creatine kinase; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; oxLDL, oxidized low‐density protein; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 2.

Comparison in 2‐Dimensional and Doppler Echocardiographic Indices of the 3 Groups at Enrollment ( )

)

| 10‐mg Group (n = 47) | 40‐mg Group (n = 48) | Control Group (n = 97) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAD, mm | 36.85 ± 2.58 | 37.06 ± 2.45 | 31.78 ± 1.99 | 0.000 |

| LVEDD, mm | 58.85 ± 5.08 | 58.81 ± 4.67 | 47.39 ± 2.95 | 0.000 |

| LVESD, mm | 43.00 ± 4.27 | 43.33 ± 3.76 | 20.35 ± 2.43 | 0.000 |

| LVEF, % | 33.72 ± 3.94 | 33.13 ± 4.19 | 59.32 ± 4.18 | 0.000 |

| E, m/sec | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.000 |

| A, m/sec | 0.53 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 0.000 |

| E/A | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 1.03 ± 0.16 | 1.24 ± 0.15 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: A, late transmitral flow velocity; E, early transmitral flow velocity; LAD, left atrial diameter; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end‐systolic dimension. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Comparison of serum lipid, oxLDL, hsCRP, CK, ALT, cEMPs, and cEPCs between the 2 study groups at the end of the study:

At the end of the study, the levels of serum TC, LDL, oxLDL, hsCRP, cEMPs (P < 0.001) significantly decreased, but the levels of cEPCs (P = 0.014) significantly increased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group in contrast to the 10‐mg atorvastatin group. Subjects did not differ in CK and ALT between the 2 study groups at the end of the study (P > 0.05) (Table 3). The multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that only receiving 40 mg of atorvastatin had significant effect on the levels of cEPCs (β = 0.252,P = 0.014).

Table 3.

Comparison of Serum Lipid, OxLDL, HsCRP, cEMPs, cEPCs, CK, and ALT Between 2 Study Groups at the End of the Study (  )

)

| TC, mmol/L | LDL, mmol/L | oxLDL, mmol/L | hsCRP, mg/L | cEMPs, n/µL | cEPCs, % | CK, mmol/L | ALT, mmol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10‐mg group (n = 47) | 4.60 ± 0.63 | 2.55 ± 0.57 | 2.25 ± 1.13 | 6.36 ± 3.57 | 1847.98 ± 180.26 | 0.055 ± 0.019 | 103.58 ± 36.04 | 30.62 ± 5.90 |

| 40‐mg group (n = 48) | 4.16 ± 0.62 | 2.19 ± 0.69 | 1.50 ± .66 | 3.43 ± 1.99 | 1683.75 ± 118.58 | 0.065 ± .018 | 106.65 ± 7.03 | 32.37 ± 6.62 |

| Significance | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.683 | 0.176 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; cEMPs, circulating endothelial‐derived microparticles; cEPCs, circulating endothelial progenitor cells; CK, creatine kinase; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; oxLDL, oxidized low‐density protein; TC, total cholesterol. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Characterization of cEPCs:

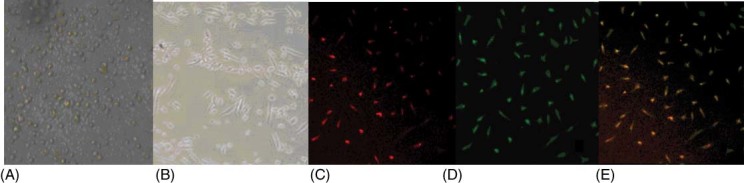

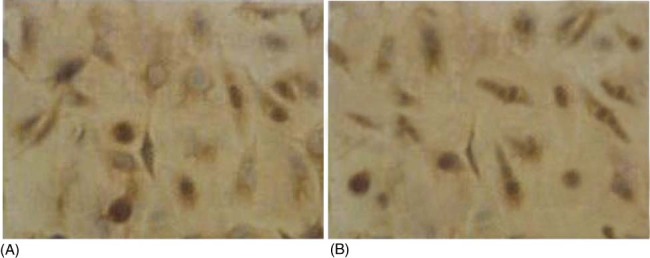

After 5 days in culture, the liked endothelial fusiform cells were differentiated from the isolated mononuclear cells (Figure 1A,B). EPCs were displayed as dual‐staining cells under inverted fluorescence microscope after being stained by Di‐acLDL and FITC‐labeled UEA‐I (Figure 1C–E). The results of EPCs examined by immunohistochemistry are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Culture and characterization of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). (A) Isolated mononuclear cells from peripheral blood (×200). (B) After 5 days in culture, adherent cells displayed as fusiform‐like endothelial cells (×200) . (C) After 14 days in culture, EPCs displayed as red‐staining cells under inverted fluorescence microscope after uptaking 1,1′‐dioctadecyl‐3,3,3′,3′‐tetramethylindocarbocyanine‐labeled acetylated low‐density lipoprotein (red ×200). (D) After 14 days in culture, EPCs displayed as green‐staining cells under inverted fluorescence microscope after staining by fluorescein‐5‐isothiocyanate–labeled Ulex europaeus agglutinin I (green ×200). (E) After 14 days in culture, EPCs displayed as dual‐staining cells under inverted fluorescence microscope (yellow ×200).

Figure 2.

Results of immunohistochemistry. (A) Positive reaction was examined between adherent cells and anti‐CD34+‐IgG. Stained multiple granular was visible in cytoplasm but not in Nuclear of cells (Dimethyl aminoazobenzene. DAB dyeing process ×400). (B) Negative control (without anti‐CD34+‐IgG).

Discussion

At the beginning of this study, there were no significant differences in age, sex, lipids, oxLDL, hsCRP, cEMPs, and cEPCs between the 2 study groups. At the end of this study, the levels of serum TC, oxLDL, LDL, hsCRPm, and cEMPs significantly decreased, but the cEPCs significantly increased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group in contrast to the 10‐mg atorvastatin group.

Various factors are involved in the mechanisms of EMP generation.17, 18 Tumor necrosis factor‐α, lipopolysaccharide, or oxLDL stimulation of cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells results in an increase in the release of EMP expressing surface tissue factor.19, 20 At present, the increasing levels of cEMPs can reflect endothelium impairment. In patients with inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy, endothelial function improvement is associated with a significant drop in circulating microparticles.21 When exposed to a proapoptotic milieu, EPCs undergo fragmentation into microparticles. Increased microparticles shedding from EPCs may reduce cEPC levels and may thus contribute to increased aortic stiffness besides traditional risk factors.22 Reduced cEPCs, impaired EPC generation/function, and increased production of microparticles might be the mechanisms responsible for the increased ischemic damage seen in db/db mice.11 Currently, the ratio of EMPs to EPCs is regarded as a quantitative and clinically feasible measurement of vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes.13 One study indicated fluvastatin could decrease EMP release from human coronary artery endothelial cells.14 At present, stabilizing cellular membranes to decrease the release of EMPs is considered as a target of vascular therapy.15

At the end of this study, the number of peripheral cEPCs was significantly elevated in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group in comparison with the 10‐mg atorvastatin group. A previous study suggested ICM is associated with selective impairment of progenitor cell function in the bone marrow and in the peripheral blood, which may contribute to an unfavorable LV remodeling process. It has been proposed that migration of EPCs was more than an inflammatory response23; cEPCs could make a significant contribution to blood vessel formation and recovery of endothelial cells.24 EPCs could rapidly recruit to myocardium and mediate a protective effect of ischemic preconditioning in patients with acute MI.25 Embryonic EPCs could induce blood vessel growth and cardioprotection in severe ischemic conditions, providing a readily available source to study the mechanisms of neovascularization and tissue recovery.26 Therefore, EPCs were regarded as a potential versatile tool for the treatment of ICM.27 In the present study, the levels of cEMPs significantly decreased, but the cEPCs significantly increased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group in contrast to the 10‐mg atorvastatin group. The multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that only receiving 40‐mg atorvastatin had a significant effect on the levels of cEPCs, which suggested that 40‐mg atorvastatin might contribute to a stronger effect on blood vessel formation ability and recovery of endothelial cells in patients with ICM in contrast to 10‐mg atorvastatin. But the exact effect of statins on peripheral cEPCs and EMPs in patients with ICM remains to be confirmed by further studies. Although the significantly increasing number of cEPCs in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group might be partly due to lower suppressing effects on EPCs by oxidation and inflammation because of lower levels of oxidation and inflammation in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group, the exact mechanism was unclear.

At the end of this study, the levels of serum TC, LDL, and oxLDL significantly decreased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group. Findings suggested that 40 mg of atorvastatin could significantly decrease the levels of serum oxLDL and alleviate the levels of TC oxidation as well as decrease the levels of TC and LDL, in contrast to 10 mg of atorvastatin. A previous study demonstrated that oxLDL could induce endothelial cell28 damage and result in an increase in the release of EMP.29 In addition, at the end of this study, the levels of serum hsCRP significantly decreased in the 40‐mg atorvastatin group. It suggested that 40 mg of atorvastatin could significantly alleviate the levels of systemic inflammation, in contrast to 10 mg of atorvastatin. A previous study demonstrated that endothelial cell apoptosis and cEMP release were associated with IL‐6 levels and C‐reactive protein in men and might be partially responsible for the increased cardiovascular risk associated with subclinical inflammation. However, EMPs could induce inflammation in acute lung injury. Increased platelet, leukocyte, and endothelial microparticles predict enhanced coagulation and vascular inflammation in pulmonary hypertension. And serum hsCRP levels were found to be significantly increased in patients with ICM compared to controls.30 Furthermore, in all previous studies using statins to treat acute coronary syndromes, the benefit correlated with reductions in CRP.30 In the present study, in comparison with 10‐mg atorvastatin, 40‐mg atorvastatin was found to significantly decrease the levels of cEMPs and increase the number of cEPCs, possibly in part because of its stronger effect on inflammation and oxidation.

In recent years, several studies have demonstrated that statins might be associated with the decreased systemic inflammation and improved prognosis.31, 32 Moreover, treatment with atorvastatin 80 mg continued to significantly decrease the risk of any cardiovascular event33, 34 and repeat revascularizations35 over time compared to atorvastatin 10 mg in patients who had survived previous events. It is noteworthy that treatment with atorvastatin 80 mg is without sacrifice of safety compared to atorvastatin 10 mg.36 Atorvastatin 40 mg was used in the present study because of the lower tolerance to statins in southerners in China, owing to their lower weight . Subjects did not differ in CK and ALT between the 2 groups at the end of study. Our findings suggest that atorvastatin 40 mg might contribute to improving vascular formation and endothelium impairment in patients with ICM without sacrifice of safety compared to atorvastatin 10 mg.

There were several limitations in the present study. The patient number was too low. Also, there was not 2 different classes of statins compared in the current study. The abilities of mobilization and differentiation of EPCs were not examined. Because the iconographic examination involving myocardial metabolism was not performed, the findings of the study are less convincing.

Conclusion

In comparison with 10 mg of atorvastatin, 40 mg of atorvastatin might decrease the levels of cEMPs and increase the number of cEPCs in patients with ICM. Moreover, the effect might be independent of the decrease in lipids, oxLDL, and hsCRP. The study findings might provide support for the use of statins in patients with ICM.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mr. Wenbiao Zhu and the Department of Medical Technology for their technical assistance and to Chang Tu in the Department of Cardiology, at the first affiliated hospital of Sun Yat‐sen University, for his good advice.

References

- 1. Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhattacharya V, McSweeney PA, Shi Q, et al. Enhanced endothelialization and microvessel formation in polyester grafts seeded with CD34(+) bone marrow cells. Blood. 2000;95:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gehling UM, Ergun S, Schumacher U, et al. In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133‐positive progenitor cells. Blood. 2000;95:3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crosby JR, Kaminski WE, Schatteman G, et al. Endothelial cells of hematopoietic origin make a significant contribution to adult blood vessel formation. Circ Res. 2000;87:728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, et al. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89:E1–E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt‐Lucke C, Rossig L, Fichtlscherer S, et al. Reduced number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells predicts future cardiovascular events: proof of concept for the clinical importance of endogenous vascular repair. Circulation. 2005;111:2981–2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Valgimigli M, Rigolin GM, Fucili A, et al. CD34+ and endothelial progenitor cells in patients with various degrees of congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:1209–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kissel CK, Lehmann R, Assmus B, et al. Selective functional exhaustion of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow of patients with postinfarction heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2341–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lacroix R, Sabatier F, Mialhe A, et al. Activation of plasminogen into plasmin at the surface of endothelial microparticles: a mechanism that modulates angiogenic properties of endothelial progenitor cells in vitro. Blood. 2007;110:2432–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Curtis AM, Zhang L, Medenilla E, et al. Relationship of microparticles to progenitor cells as a measure of vascular health in a diabetic population. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2010;78:329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tramontano AF, O'Leary J, Black AD, et al. Statin decreases endothelial microparticle release from human coronary artery endothelial cells: implication for the Rho‐kinase pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inzhutova AI, Larionov AA, Petrova MM, et al. Stabilization of cellular membranes as a target of vascular therapy [in Russian]. Kardiologiia. 2011;51:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Itabe H, Yamamoto H, Imanaka T, et al. Sensitive detection of oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein using a monoclonal antibody. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sapet C, Simoncini S, Loriod B, et al. Thrombin‐induced endothelial microparticle generation: identification of a novel pathway involving ROCK‐II activation by caspase‐2. Blood. 2006;108: 1868–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Guerin AP, et al. In vivo shear stress determines circulating levels of endothelial microparticles in end‐stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2007;49:902–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kagawa H, Komiyama Y, Nakamura S, et al. Expression of functional tissue factor on small vesicles of lipopolysaccharide‐stimulated human vascular endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 1998;91:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nomura S, Shouzu A, Omoto S, et al. Activated platelets and oxidized LDL induce endothelial membrane vesiculation: clinical significance of endothelial cell derived microparticles in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2004;10: 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pirro M, Schillaci G, Bagaglia F, et al. Microparticles derived from endothelial progenitor cells in patients at different cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen J, Chen S, Chen Y, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cellular membrane microparticles in db/db diabetic mouse: possible implications in cerebral ischemic damage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E62–E71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rabelink TJ, de Boer HC, de Koning EJ, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells: more than an inflammatory response? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kupatt C, Horstkotte J, Vlastos GA, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells are rapidly recruited to myocardium and mediate protective effect of ischemic preconditioning via “imported” nitric oxide synthase activity. Circulation. 2005;111:1114–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kupatt C, Horstkotte J, Vlastos GA, et al. Embryonic endothelial progenitor cells expressing a broad range of proangiogenic and remodeling factors enhance vascularization and tissue recovery in acute and chronic ischemia. FASEB J. 2005;19:1576–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pompilio G, Capogrossi MC, Cannata A, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells: a potential versatile tool for the treatment of ischemic cardiomyopathies‐a clinician's point of view. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95:S34–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zorn‐Pauly K, Schaffer P, Pelzmann B, et al. Oxidized LDL induces ventricular myocyte damage and abnormal electrical activity–role of lipid hydroperoxides. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Senes M, Erbay AR, Yilmaz FM, et al. Coenzyme Q10 and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein in ischemic and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nomura S. Statin and endothelial cell‐derived microparticles. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:377–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shishehbor MH, Patel T, Bhatt DL. Using statins to treat inflammation in acute coronary syndromes: Are we there yet? Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okura H, Asawa K, Kubo T, et al. Impact of statin therapy on systemic inflammation, left ventricular systolic and diastolic function and prognosis in low risk ischemic heart disease patients without history of congestive heart failure. Intern Med. 2007;46:1337–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li MC, Liu JL. Effect of atorvastatin on cardiac function and plasma c‐reactive protein and uric acid levels in patients ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Med Res. 2008;37:86–88. [Google Scholar]

- 33. LaRosa JC, Deedwania PC, Shepherd J, et al. Comparison of 80 versus 10 mg of atorvastatin on occurrence of cardiovascular events after the first event (from the Treating to New Targets [TNT] trial). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tikkanen MJ, Szarek M, Fayyad R, et al. Total cardiovascular disease burden: comparing intensive with moderate statin therapy insights from the IDEAL (Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2353–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson C, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of atorvastatin 10 mg versus 80 mg in reducing major cardiovascular events and repeat revascularization in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention (post hoc analysis of the Treating to New Targets [TNT] Study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of atorvastatin‐induced very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease (a post hoc analysis of the treating to new targets [TNT] study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]