Abstract

Background:

Symptomatic mitral restenosis develops in up to 21% of patients after percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy (PBMV), and most of these patients undergo mitral valve replacement (MVR).

Hypothesis:

Repeating PBMV (re‐PBMV) might be an effective and less‐invasive treatment for these patients.

Methods:

Forty‐seven patients with post‐PBMV mitral restenosis and unfavorable valve characteristics were assigned either to re‐PBMV (25 cases; mean age 40.7 ± 11 y, 76% female) or MVR (22 cases; mean age 47 ± 10 y, 69% female) at 51 ± 33 months after the prior PBMV. The mean follow‐up was 41 ± 32 months and 63 ± 30 months for the re‐PBMV and MVR groups, respectively.

Results:

The 2 groups were homogenous in preoperative variables such as gender, echocardiographic findings, and valve characteristics. Patients in the MVR group were older, with a higher mean New York Heart Association functional class, mean mitral valve area, mitral regurgitation grade, and right ventricular systolic pressure (P = 0.03), and more commonly were in AF. There were 3 in‐hospital deaths (all in the MVR group) and 4 during follow‐up (3 in the MVR group and 1 in the re‐PBMV group). Ten‐year survival was significantly higher in re‐PBMV vs MVR (96% vs 72.7%, P<0.05), but event‐free survival was similar (52% vs 50%, P = 1.0) due to high reintervention in the re‐PBMV group (48% vs 18.1%, P = 0.02).

Conclusions:

In a population with predominantly unfavorable characteristics for PBMV, short‐ and long‐term outcomes are both reasonable after re‐PBMV with less mortality but requiring more reinterventions compared with MVR. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

Since its first introduction in 1984,1, 2 percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy (PBMV) has been shown to be a safe and effective treatment for rheumatic mitral stenosis.3, 4 Mitral restenosis after previous PBMV occurs at the rate of 7%–21% with the incidence increasing after 5 years of follow‐up.4, 5, 6 The feasibility and encouraging outcome of repeated PBMV in patients with favorable valve morphology has been previously reported,7, 8 but data on patients with unfavorable valve characteristics is scarce, with less‐impressive long term results.9, 10 Although most of these patients currently undergo mitral valve replacement (MVR),3 it is unknown whether some of these patients may benefit more from a repeat PBMV (re‐PBMV). Compared with valve replacement, PBMV is less invasive, free from MVR‐related complications, and cost effective,11 but grave complications such as cardiac rupture or massive mitral regurgitation (MR) needing emergency operations may occur.12 The main aim of this study was to address short‐ and long‐term outcomes of patients with symptomatic mitral valve restenosis and unfavorable valve morphology undergoing re‐PBMV or MVR.

Methods

Between November 1999 and December 2009, 1745 patients underwent PBMV at our institution. Of these, 110 patients (6.3%) required reintervention due to mitral restenosis during follow up. Forty‐seven patients (2.7%) in this group had unfavorable valve characteristics and were assigned either to re‐PBMV (25 cases with mean age 40.7 ± 11 y, 76% female) or MVR (22 cases with mean age 47 ± 10 y, 69% female) at 51 ± 33 months after the initial balloon valvotomy. Inclusion criteria were symptomatic mitral restenosis with a mitral valve area (MVA) ≤1.5 cm2, unfavorable valve characteristics, and informed consent. Exclusions included those with associated severe MR (grade 4), significant aortic stenosis or regurgitation, active endocarditis, or contraindications to trans‐septal puncture (eg, left atrial thrombus lying against the interatrial septum). Criteria for choosing MVR or re‐PBMV in these patients were at the discretion of the attending physician and patient preference. Essentially, those patients who denied open heart surgery and preferred a less‐invasive and less‐expensive procedure because of economic restraints, and those who were considered at very high risk for surgery (eg, pregnant women, poor general health, and high pulmonary pressure especially in the presence of right ventricular enlargement and/or systolic dysfunction) were offered to undergo re‐PBMV. Demographic, clinical, and procedural variables were collected retrospectively using a review of medical records and telephone contact.

The PBMV was performed in a fasting state under local anesthesia and mild sedation by the antegrade trans‐septal approach with a stepwise dilation technique using Inoue balloon catheter (Toray Industries, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), beginning with a small diameter and re‐evaluating the transmitral gradient and degree of MR after each inflation. The reference balloon size was determined according to the height of the patient.13 Complete hemodynamic measurements of the right and the left heart, including simultaneous left atrial pressure and left ventricular end diastolic pressures, were made immediately before and after the valvuloplasty. The PBMV was terminated once a satisfactory hemodynamic result was achieved, defined as a decrease of at least one‐half of the initial transmitral gradient with no further reduction despite 2 more dilation using balloon sizes in 0.5–1‐mm increments.14 Mitral valve replacement was performed as standard technique with median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass using bileaflet metallic valves (St. Jude or Medtronic‐Hall valves).

Transthoracic echocardiography was done in all patients at least 1 week prior to the procedure, and transesophageal echocardiography was performed only in patients assigned to re‐PBMV on the morning of the procedure; echocardiographic score of the mitral apparatus, baseline MVA, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and presence of MR were determined. Mitral valvular and subvalvular morphology was graded according to the Wilkins scoring system, which assigns higher scores to more severe disease.15 Left atrial diameter was measured in M‐mode from a short axis parasternal section at the level of the aortic valve.16 Mitral valve area was calculated by planimetry or, in the absence of significant MR, from pressure half‐time.17 Semiquantitative estimation of MR was made with color flow mapping in parasternal long axis and apical 4‐chamber views. “Unfavorable valve morphology” was defined by the cardiologists conducting the study as a Wilkins echo score of 9–12 and/or MR severity grade of 2–3+. Peak transmitral pressure gradients (PTMPG) and right ventricular systolic pressures (RVSP) were estimated using continuous‐wave Doppler echocardiography. Left atrial pressure and mean transmitral pressure gradients (MTMPG) were measured during catheterization. Optimal commissurotomy was defined as a valve area increment ≥50% or a final valve area >1.5 cm2, without resulting >3+ angiographic MR. Endpoints of follow‐up were death or reintervention (surgical or transcatheter).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical values, expressed as percentages, were compared by χ 2 or Fisher exact test, whereas continuous data, shown as mean ± SD, were compared by Mann‐Whitney U test or independent samples t test. Comparison for long‐term survival between groups was performed using the log‐rank test. Multivariate Cox regression hazards analyses were used to identify independent correlates of long‐term event‐free survival. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Data storage and analysis were performed using SPSS version 15.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Patients in the MVR group were older, with a higher New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA‐FC), MVA, MR grade, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure, as well as higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) and lower left ventricular function. Left atrial sizes and pressures, echo scores, and transvalvular gradients were similar between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical, Echocardiographic, and Angiographic Variables

| Variable | re‐PBMV (n = 25) | MVR (n = 22) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 6/19 (24%) | 7/15 (31%) | 0.74 |

| Age (y) | 40.7 ± 11 | 47 ± 10.3 | 0.043a |

| NYHA‐FC (mean) | 2.64 ± 0.63 | 3.18 ± 0.73 | 0.009a |

| LAD (mm) | 48.8 ± 4.6 | 51.3 ± 6.2 | 0.14 |

| AF (%) | 8 (32) | 14 (63.3) | 0.01a |

| MVA (cm2) | 0.97 ± 0.1 | 1.15 ± 0.34 | 0.012a |

| Echo score | 9.56 ± 1.47 | 10.59 ± 2.48 | 0.08 |

| MR | 1.52 ± 0.63 | 2.05 ± 0.99 | 0.03a |

| LVEF | 0.5 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.03a |

| PTMPG (echo, mm Hg) | 18.7 ± 6.1 | 16.7 ± 4.5 | 0.26 |

| MTMPG (angio, mm Hg) | 12.5 ± 6.1 | 11.7 ± 5.3 | 0.6 |

| LAP (mm Hg) | 26.7 ± 6.75 | 25 ± 5.8 | 0.34 |

| RVSP (mm Hg) | 57 ± 16 | 69.4 ± 24.4 | 0.036a |

| Follow‐up (y) | 41 ± 32 | 63 ± 30 | 0.055 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; LAD, left atrial dimension; LAP, left atrial pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, mitral regurgitation; MTMPG, angiographic mean transmitral pressure gradient; MVA, mitral valve area; MVR, mitral valve replacement; NYHA‐FC, New York Heart Association functional class; PTMPG, echo peak transmitral pressure gradient; re‐PBMV, repeat percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure.

P value is significant.

Immediate and In‐Hospital Outcomes

Re‐PBMV was successfully completed in 22 patients (88%). Two patients (8%) developed severe MR (grade 4+) after re‐PBMV, and 1 patient (4%) experienced hemopericardium and tamponade requiring emergent surgery. There were no hospital deaths in this group. Mitral valve replacement was successfully completed in all patients, but 3 (13.6%) died before hospital discharge due to operation‐related complications (1 hemorrhage, 1 cardiogenic shock, and 1 severe paravalvular leak) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Periprocedural and Late Complications in Both Groups

| Complication | re‐PBMV | MVR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MR | 2 | NA | |

| Tamponade | 1 | NA | |

| IE | 0 | 1 | 0.09 |

| In‐hospital death | 0 | 3 | 0.02a |

| Overall mortality | 1 | 6 | 0.03a |

| Restenosis/treatment failure | 8 | NA | |

| Prosthesis malfunction | NA | 3 | |

| Reintervention | 12 | 4 | 0.04a |

| Event‐free survival | 13/25 (52%) | 11/22 (50%) | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; MR, mitral regurgitation; MVR, mitral valve replacement; NA, not applicable; re‐PBMV, repeat percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy.

P value is significant.

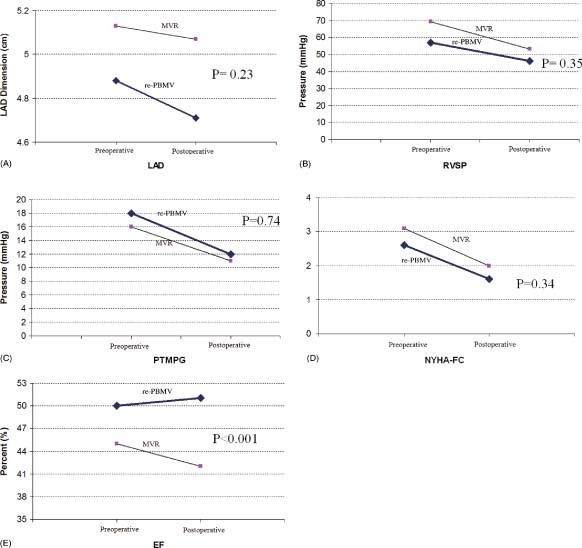

As expected, MVA was increased after re‐PBMV from 0.97 ± 0.1 to 1.61 ± 0.17 cm2 (P<0.001) and left atrial pressure and MTMPG were decreased from 26.7 ± 6.7 mm Hg to 17.7 ± 4.4 mm Hg, and from 12.5 ± 6.1 mm Hg to 2.1 ± 1.5 mm Hg, respectively (P<0.001 in both). Also, there was a significant decrease in left atrial dimension (from 48.8 ± 4.6 mm to 47.1 ± 4.8 mm in re‐PBMV vs from 51.3 ± 6.2 mm to 50.7 ± 7.1 mm in the MVR group, P = 0.01), RVSP (from 57 ± 16 mm Hg to 46.6 ± 21.1 mm Hg in re‐PBMV vs from 69.3 ± 24.3 mm Hg to 53.9 ± 18.1 mm Hg in MVR group, P<0.001), PTMPG (from 18.7 ± 6.1 mm Hg to 12.2 ± 3.9 mm Hg in re‐PBMV vs from 16.7 ± 4.5 mm Hg to 10.9 ± 3.9 mm Hg in the MVR group, P<0.001), and NYHA‐FC (from 2.6 ± 0.6 to 1.6 ± 1 in re‐PBMV vs from 3.1 ± 0.7 to 2 ± 0.4 in the MVR group, P<0.001) in both groups, but the difference between groups after the procedure was not statistically significant (Figure 1A–D). The LVEF was not changed in the re‐PBMV group (50 ± 6% before and 51 ± 5% after PBMV, P = 0.42) but was significantly reduced in the MVR group (45 ± 7% before and 42 ± 7% after MVR, P<0.001) (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Comparison of preoperative and postoperative parameters in both groups. (A) Left atrial dimension. (B) Right ventricular systolic pressure. (C) Echocardiographic peak transmitral pressure gradient. (D) NYHA functional class. (E) Ejection fraction. Abbreviations: EF, ejection fraction; LAD, left atrial dimension; MVR, mitral valve replacement; NYHA‐FC, New York Heart Association functional class; PTMPG, echo peak transmitral pressure gradient; re‐PBMV, repeat percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure.

Clinical Follow‐Up

Patients With Re‐PBMV:

The mean follow‐up was 41 ± 32 months. Two patients were lost during follow‐up. During this time, 1 patient died (4%) about 18 months after the procedure due to intractable right‐sided heart failure, and 8 (32%) patients required reintervention due to restenosis (4 patients) or increase in MR severity (4 patients). They were treated with re‐PBMV (2 patients) or MVR (6 patients). Overall, 13 patients (52%) were alive without further valvular intervention at end of follow‐up (Table 2). All of these patients were in NYHA class I or II at follow‐up.

Patients With MVR:

The mean follow‐up was 63 ± 30 months. No patient was lost to follow‐up. At this period, 1 patient (4.5%) suffered from prosthetic valve endocarditis 11 months after surgery and underwent reoperation, but died 2.5 months later due to refractory heart failure. There were 2 other deaths (9%) due to extensive ischemic stroke (1 patient) and massive gastrointestinal bleeding with warfarin overdose (1 patient). Also, 3 (13.6%) patients required redo MVR due to severe paravalvular leak (1 patient, 2 months after the initial operation) and prosthetic valve malfunction (2 patients). Overall, 11 patients (50%) were alive at end of follow‐up without further valvular intervention (Table 2).

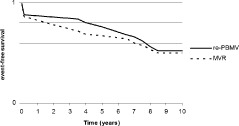

Finally, total mortality was higher in the MVR group (27.2% vs 4%, P = 0.03), and the re‐PBMV group required more reintervention during follow‐up (48% vs 18%, P = 0.04), but immediate periprocedural complications and mortality (12% with re‐PBMV vs 13.6% with MVR, P = 0.98) and also overall event‐free survival was similar between groups (52% with re‐PBMV vs 50% with MVR, P = 1.0) (Figure 2). On multivariate analysis, none of the important variables (age, type of procedure [re‐PBMV or MVR], MR severity, RVSP, MVA, and NYHA‐FC after, or echocardiographic valve score before the procedures) were independently powerful indicators of long‐term event‐free survival (χ 2 = 0.3, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, P = 0.84).

Figure 2.

Event‐free survival in both groups. Abbreviations: MVR, mitral valve replacement; re‐PBMV, repeat percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy.

Discussion

We compared the results of MVR or re‐PBMV in patients with restenosis after a previous PBMV who had unfavorable valve morphology. Our results show that re‐PBMV can be performed safely in these patients, with results comparable to MVR. There were no significant differences in hemodynamic measurements before and after the procedure between both groups, but LVEF was significantly reduced after MVR. After re‐PBMV in these special patients, the short‐ and long‐term survival rate was significantly better than MVR, but about half of patients needed reintervention during follow‐up, undermining the palliative nature of the procedure in patients with unfavorable valve characteristics.

Only few studies have particularly examined the utility and feasibility of re‐PBMV for mitral restenosis, and with conflicting results, mainly due to different patient‐inclusion criteria.7, 8, 18, 19 Iung et al7 included relatively young patients at a mean age of 39 years with bilateral commissural fusion, excluding those with significant valvular calcification or associated comorbidity, with an immediate 91% success rate and 5‐year survival rate of about 74%. Pathan et al8 included older patients at a mean age of 58 years with more deformed valves, 50% having a Wilkins echo score >8, and 77% having valve calcification, with an immediate success rate of 75% and 3‐year survival rate of 71%. Turgeman et al18 included patients at a mean age of 45 years with echo findings similar to Pathan's study8 and achieved an immediate success rate of 82% with no deaths at a short follow‐up of about 25 months. Our patients had a higher mean echo score compared with the previous studies (about 9.5), and successful PBMV was achieved in 88% of cases without any hospital deaths or stroke with a long‐term survival rate of 96%. The better survival rate in our study can be explained by the relatively young patient population and presence of less comorbidity in comparison with the mentioned studies. Recently, Kim et al19 compared the long‐term outcome of re‐PBMV and MVR in patients with restenosis and previous valvotomy. Thirty‐two patients underwent re‐PBMV, and MVR was done in 59. Although the mean echo score of the re‐PBMV group was 8.4 ± 1.0, there was no procedural failure in this group and 62.5% of results were classified as optimal. This is surprising, because valve morphology and functional anatomy are the main predictors of successful PBMV, and patients who have a history of prior PBMV have more deformed valve anatomy.15 On the other hand, there were no deaths in the immediate postoperative period or during a follow‐up of almost 15 years in either group. Event‐free survival was similar between the 2 groups up to 4 years after the procedure. However, beyond 4 years there was an increased incidence of additional intervention, mostly MVR or re‐PBMV in patients who underwent re‐PBMV. Our study, with a comparable long‐term follow‐up, showed a similar event‐free survival and better overall survival of patients undergoing re‐PBMV with respect to the MVR group, more likely reflecting the real‐life scenario of patients with restenosis after a previous valvotomy.

Our study findings resemble those of Feldman et al20 and Uddin et al,14 who showed that a high Wilkins mitral score is not a very robust predictor of poor results after PBMV. Previous studies have shown that the occurrence of MR after PBMV is not clearly related to the presence of more severe valvular and subvalvular deformity.20, 21 Remarkably, Feldman et al20 found an increase of ≥2+ in MR severity after the procedure, more commonly in younger patients with lower echocardiographic scores.20 Although the occurrence of MR during valvuloplasty cannot be predicted precisely, one important key, which we employ routinely in our center, is using stepwise inflations with the Inoue balloon catheter and evaluating MR after each inflation, resulting in termination of the procedure before MR severity becomes unacceptable. This may explain the relatively low incidence of severe MR (8%) in our patients, despite having unfavorable valve morphology.

Other studies have emphasized commissural morphology and chordae tendineae length as better predictors of outcome than Wilkins echo score in patients with mitral restenosis,18, 22, 23 but unfortunately we had used only the latter to determine valve morphology. Patients with mitral restenosis in whom the main mechanism is symmetrical commissural refusion gain greater benefit from repeat valvuloplasty compared with patients with restenosis in whom the pathologic mechanism of restenosis is mainly subvalvular.20

Surgical valve repair is another treatment option for patients with mitral restenosis after previous PBMV. However, because of more extensive valvular and subvalvular involvement in these patients, MVR is usually preferred.7

There are no randomized clinical trials comparing re‐PBMV with MVR in patients with mitral restenosis and previous history of valvotomy. Pathan et al8 studied these 2 groups in a non–head‐to‐head model and found a better outcome by MVR rather than re‐PBMV. We compared these 2 groups in a similar design and showed a similar event‐free survival, but the overall survival in the re‐PBMV group was better. Hospital mortality of our patients who underwent MVR (13.6%) was significantly higher than that reported by Pathan et al (5%). The risk of perioperative mortality and early death after MVR increases with age, high NYHA‐FC, and associated comorbid diseases.24, 25 The relatively high in‐hospital mortality of our MVR group might be due to inclusion of more patients with advanced disease, having higher RVSP (mean about 69 mm Hg) and a higher prevalence of AF (63.3%) (Table 1).

Study Limitations

Although this retrospective study has the largest number of patients undergoing PBMV (n = 1745) that has ever been reported from a single center, it may be limited by the relatively small number of re‐PBMV cases (n = 47), which may impair the exact analysis of predictive factors for success or failure of this procedure. These results are from a single tertiary referral center with a high volume of valvuloplasty performed and may not be applicable to the overall population of patients undergoing PBMV. A valid comparison of re‐PBMV and MVR for post‐PBMV restenosis and unfavorable valve morphology requires a large randomized clinical trial, which would be difficult to organize.

Conclusion

Re‐PBMV in patients with mitral restenosis after prior PBMV and unfavorable valve morphology is feasible and at least as effective as MVR, with acceptable morbidity and lower mortality. Although MVR is the standard treatment for patients with more extensive valvular and subvalvular deformity, re‐PBMV can be offered as an alternative technique in these patients when they are at high risk of morbidity and mortality with MVR due to advanced age or the presence of associated significant comorbid diseases, or simply when they refuse to undergo open heart surgery. This less‐invasive method of therapy may provide adequate symptom relief for a period of time, or maybe indefinitely in some cases, with a low procedural risk. The decision may be more difficult in patients with deformed valves who are at low risk for surgery. Percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy offers a reasonable symptom relief on a minimally invasive basis, whereas MVR is accompanied by more relief of symptoms at the expense of significant morbidity and mortality.

References

- 1. Inoue K, Owaki T, Nakamura T, et al. Clinical application of transvenous mitral commissurotomy by a new balloon catheter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;87:394–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lock JE, Khalilullah M, Shrivastava S, et al. Percutaneous catheter commissurotomy in rheumatic mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1515–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dean LS, Mickel M, Bonan R, et al. Four‐year follow‐up of patients undergoing percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy: a report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1452–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iung B, Cormier B, Ducimetiere P, et al. Functional results 5 years after successful percutaneous mitral commissurotomy in a series of 528 patients and analysis of predictive factors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palacios I, Block PC, Brandi S, et al. Percutaneous balloon valvotomy for patients with severe mitral stenosis. Circulation. 1987;75:778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Desideri A, Vanderperren O, Serra A, et al. Long‐term (9 to 33 months) echocardiographic follow‐up after successful percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1602–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iung B, Garbarz E, Michaud P, et al. Immediate and mid‐term results of repeat percutaneous mitral commissurotomy for restenosis following earlier percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1683–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pathan AZ, Mahdi NA, Leon MN, et al. Is redo percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty (PMV) indicated in patients with post‐PMV mitral restenosis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuzcu EM, Block PC, Griffin B, et al. Percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy in patients with calcific mitral stenosis: immediate and long‐term outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1604–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Post JR, Feldman T, Isner J, et al. Inoue balloon mitral valvotomy in patients with severe valvular and subvalvular deformity. J Am Coll Cardiol . 1995;25:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Makoto K, Kenji O, Susumu N, et al. Mitral valve replacement after percutaneous transluminal mitral commissurotomy. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;52:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrison JK, Wilson JS, Hearne SE, et al. Complications related to percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;(suppl 2):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lau KW, Hung JS. A simple balloon‐sizing method in Inoue‐balloon percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;33:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uddin MJ, Rahman F, Salman M, et al. Percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty in patients with previous surgical mitral commissurotomy. University Heart Journal (Bangladesh). 2009;5: 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilkins GT, Weyman AE, Abascal VM, et al. Percutaneous balloon dilatation of the mitral valve: an analysis of echocardiographic variables related to outcome and the mechanism of dilatation. Br Heart J. 1988;60:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, et al. Recommendations regarding quantitation in M‐mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic measurements. Circulation. 1978;58:1072–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palacios IF. What is the gold standard to measure mitral valve area postmitral balloon valvuloplasty? Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;33:315–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turgeman Y, Atar S, Suleiman K, et al. Feasibility, safety, and morphologic predictors of outcome of repeat percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim JB, Ha JW, Kim JS, et al. Comparison of long‐term outcome after mitral valve replacement or repeated balloon mitral valvotomy in patients with restenosis after previous balloon valvotomy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1571–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feldman T, Carroll JD, Isner JM, et al. Effect of valve deformity on results and mitral regurgitation after Inoue balloon commissurotomy. Circulation. 1992;85:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abascal VM, Wilkins GT, Choong CY, et al. Mitral regurgitation after percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty in adults: evaluation by pulsed Doppler echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–e231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levin TN, Feldman T, Bednarz J, et al. Transesophageal echocardiographic evaluation of mitral valve morphology to predict outcome after balloon mitral valvotomy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaffin JS, Daggett WM. Mitral valve replacement: a nine year follow‐up of risks and survivals. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979;27:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salomon NW, Stinson EB, Griepp RB, et al. Patient‐related risk factors as predictors of results following isolated mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]