Abstract

Background

Whether additional benefit can be achieved with the use of statin treatment in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) remains undetermined.

Hypothesis

Statin treatment may be effective in improving cardiac function and ameliorating ventricular remodeling in CHF patients.

Methods

The PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EBM Reviews databases were searched for randomized controlled trials comparing statin treatment with nonstatin treatment in patients with CHF. Two reviews independently assessed studies and extracted data. Weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using random effects models.

Results

Eleven trials with 590 patients were included. Pooled analysis showed that statin treatment was associated with a significant increase in left ventricular ejection fraction (WMD: 3.35%, 95% CI: 0.80 to 5.91%, P = 0.01). The beneficial effects of statin treatment were also demonstrated by the reduction of left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter (WMD: −3.77 mm, 95% CI: −6.24 to −1.31 mm, P = 0.003), left ventricular end‐systolic diameter (WMD: −3.57 mm, 95% CI: −6.37 to −0.76 mm, P = 0.01), B‐type natriuretic peptide (WMD: −83.17 pg/mL, 95% CI: −121.29 to −45.05 pg/mL, P < 0.0001), and New York Heart Association functional class (WMD: −0.30, 95% CI: −0.37 to −0.23, P < 0.00001). Meta‐regression showed a statistically significant association between left ventricular ejection fraction improvement and follow‐up duration (P = 0.03).

Conclusions

The current cumulative evidence suggests that use of statin treatment in CHF patients may result in the improvement of cardiac function and clinical symptoms, as well as the amelioration of left ventricular remodeling. Copyright © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Lei Zhang, MD, Shuning Zhang, MD, and Hong Jiang, MD, contributed equally to this work. This study was supported by the Key Projects in the National Science and Technology Pillar Program in the Eleventh Five‐year Plan Period (No. 2006BAI01A04), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30871073), National High‐Tech Research and Development Program of China (No. 2006AA02A406), and Outstanding Youth Grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30725036). This work was not funded by an industry sponsor. The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Introduction

Despite advances in therapy, chronic heart failure (CHF) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. CHF is associated with activation of oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines, and neurohormones.1., 2., 3. In view of this, the class of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) was considered a promising candidate for the treatment of CHF, because statins exert diverse cellular, cholesterol‐independent effects throughout the cardiovascular system encompassing enhancement of nitric oxide synthesis, improvement of endothelial function, inhibition of inflammatory cytokines, and restoration of impaired autonomic function.4., 5., 6.

Previous experimental studies revealed that statins may attenuate pathologic myocardial remodeling and promote cardiac function in heart failure.7., 8. Thereafter, numerous trials were conducted to determine the beneficial role of statins on the failing myocardium in CHF patients; however, the results were conflicting. In order to provide a more robust estimate of the potential benefits of statin treatment, we performed a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the impact of statin treatment on cardiac function–related parameters in patients with CHF.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We performed a literature search in the PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and EBM Reviews databases to July 2009. The search terms were “statin,” “heart,” “cardiac,” “dysfunction,” “insufficiency,” “inadequacy,” and “failure,” without restrictions of language and publication form. The reference lists of studies that met our inclusion criteria was also searched for potentially relevant titles.

Studies were included in our analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) the design was a prospective, randomized controlled trial; (2) patients with established CHF, no matter the etiology, were assigned to statin treatment or control (nonstatin treatment or placebo) in addition to concurrent therapy; and (3) they reported data on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end‐systolic diameter (LVESD), B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP), or New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed all potentially eligible studies using predefined eligibility criteria and collected data from the included trials. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. We extracted details on study characteristics, patient characteristics, intervention strategies, duration of follow‐up, and clinical outcomes including LVEF, LVEDD, LVESD, BNP, and NYHA functional class.

Quality assessments were evaluated with Jadad quality scale, and a numerical score between 0 and 5 was assigned as a measure of study design.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

All endpoints were based on the change from baseline to follow‐up, and pooled effects were presented as weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using random effects models. Statistical heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistic (I2 > 50% was considered representative of significant statistical inconsistency). Meta‐regression and sensitivity analyses (including exclusion of 1 study at a time) were conducted to explore heterogeneity. Finally, on the basis of the data on LVEF, publication bias was tested using the Begg adjusted‐rank correlation test and Egger regression asymmetry test. P values were 2‐tailed, and the statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed with Stata software 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Selected Studies and Characteristics

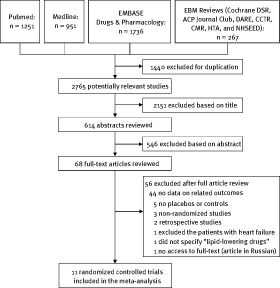

The flow of selection of studies for inclusion in the meta‐analysis is shown in Figure 1. Of the initial 4205 hits, 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 590 patients satisfying the inclusion criteria were identified and analyzed.9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19. One study by Smetanina et al20 was excluded because no full text was available for data extraction and quality assessment. A summary of baseline characteristics of the included trials is shown in Table 1. No significant differences were seen between the groups assigned statins and placebo in background CHF therapies, including angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor (or angiotensin receptor blocker) and β‐blocker therapy. Only 3 studies utilized rosuvastatin, cerivastatin, and simvastatin separately10., 11., 12.; the rest of the included trials focused on atorvastatin.9., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19. Most of the patients enrolled in this meta‐analysis had normal levels of low‐density lipoprotein.9., 10., 11., 13., 14., 15., 19. Additionally, 2 large‐scale RCTs, Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure (CORONA) and Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico–Heart Failure (GISSI‐HF) were excluded from this study due to lack of data on related endpoints.21., 22.

Figure 1.

Search flow diagram for studies included in the meta‐analysis

Table 1.

Characteristics of 11 Clinical Trials Included in the Meta‐analysis

| Authors | Publication Year | No. of Patients | Mean Age, y | Male,% | Ischemic Etiology, % | NYHA Class | Mean LVEF, % | Statin Type, Dose | Follow‐Up, mo | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleske et al9 | 2006 | 15 | 56 | 60 | 0 | I‐III | 25 | Atorvastatin, 80 mg/d | 3 | 4 |

| Krum et al10 | 2007 | 86 | 62 | 80 | 12 | II‐IV | 29 | Rosuvastatin, 10–40 mg/d | 6 | 2 |

| Laufs et al11 | 2004 | 15 | 51 | NA | 0 | II‐III | 42 | Cerivastatin, 0.4 mg/d | 5 | 3 |

| Node et al12 | 2003 | 48 | 54 | 71 | 0 | II‐III | 34 | Simvastatin, 5–10 mg/d | 3.5 | 3 |

| Sola et al13 | 2006 | 108 | 54 | 62 | 0 | II‐IV | 33 | Atorvastatin, 20 mg/d | 12 | 3 |

| Strey et al14 | 2006 | 23 | 61 | 70 | 0 | II‐III | 30 | Atorvastatin, 40 mg/d | 1.5 | 3 |

| Tousoulis et al15 | 2005 | 26 | 69 | 100 | 100 | III‐IV | 26 | Atorvastatin, 10 mg/d | 1 | 2 |

| Vrtovec et al16 | 2005 | 76 | 67 | 54 | 62 | III | 24 | Atorvastatin, 10 mg/d | 3 | 2 |

| Wojnicz et al17 | 2006 | 74 | 38 | 81 | 0 | II‐III | 28 | Atorvastatin, 40 mg/d | 6 | 3 |

| Xie et al18 | 2008 (epub) | 81 | NA | NA | 100 | II‐IV | 38 | Atorvastatin, 10 mg/d | 12 | 1 |

| Yamada et al19 | 2007 | 38 | 64 | 79 | 53 | I‐III | 34 | Atorvastatin, 10 mg/d | 31 | 5 |

Abbreviations: LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not available; NYHA, New York Heart Association

Effects of Statin Treatment

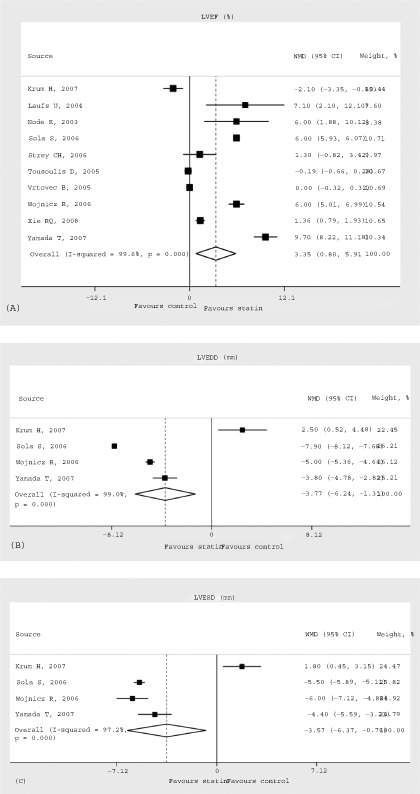

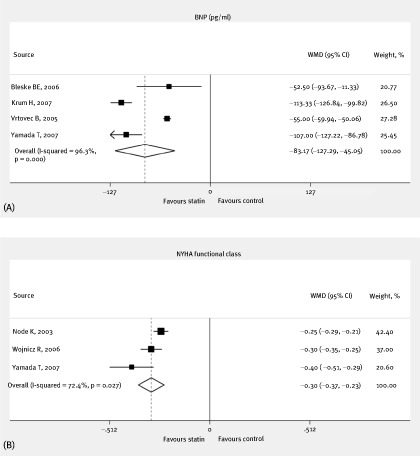

The overall pooled results with random effects analysis showed that additional statin treatment was significantly superior to standard medical therapy in terms of LVEF improvement, with a clinically and statistically significant difference of 3.35% (95% CI: 0.80 to 5.91%, P = 0.01, I2: 99.6%) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, statin therapy was similarly found to have benefits concerning LVEDD (WMD: −3.77 mm, 95% CI: −6.24 to −1.31 mm, P = 0.003, I2: 99.0%) (Figure 2B); LVESD (WMD: −3.57 mm, 95% CI: −6.37 to −0.76 mm, P = 0.01, I2: 97.2%) (Figure 2C); BNP (WMD: −83.17 pg/mL, 95% CI: −121.29 to −45.05 pg/mL, P < 0.0001, I2: 96.3%) (Figure 3A); and NYHA functional class (WMD: −0.30, 95% CI: −0.37 to −0.23, P < 0.00001, I2: 72.4%) (Figure 3B), as compared with control. All these findings suggest that statin treatment can improve cardiac function as well as ameliorate cardiac remodeling.

Figure 2.

LVEF (%) (A), LVEDD (mm) (B), and LVESD (mm) (C) during follow‐up in patients randomized to statin treatment vs nonstatin treatment with WMDs and 95% CIs. The effect size of each study is proportional to the statistical weight. The diamond indicates the overall summary estimate for the analysis; the width of the diamond represents the 95% CI. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Figure 3.

BNP (pg/mL) (A) and NYHA functional class (B) during follow‐up in patients randomized to statin treatment vs nonstatin treatment with WMDs and 95% CIs. The effect size of each study is proportional to the statistical weight. The diamond indicates the overall summary estimate for the analysis; the width of the diamond represents the 95% CI. Abbreviations: BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; CI, confidence interval; NYHA, New York Heart Association; WMD, weighted mean difference

Meta‐Regression and Sensitivity Analysis

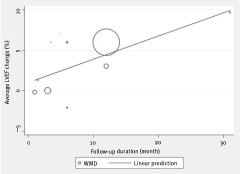

Because of the statistical heterogeneity across the enrolled studies, several exploratory meta‐regression analyses were performed to appraise the impact of different covariates on the changes in LVEF associated with statin treatment. Specifically, we did not find statistically significant association between the benefits of statin treatment and year of publication (P = 0.81), patient age (P = 0.18), patient sex (P = 0.57), CHF etiology (P = 0.44), and baseline LVEF (P = 0.08). However, we found a statistically significant association between follow‐up duration and LVEF improvement (P = 0.03), suggesting the heterogeneity could at least partially be accounted for by the difference in follow‐up duration, and a linear relationship between them is shown in Figure 4. With respect to other endpoints (LVEDD, LVESD, BNP, and NYHA functional class), meta‐regression was not performed because of inadequate power due to the low number of studies.

Figure 4.

Meta‐regression between follow‐up duration and LVEF improvement (P = 0.03). This trend supports the presence of a time‐dependent relationship (size of circle is proportional to size of trial). Abbreviations: LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; WMD, weighted mean difference

Subsequently, sensitivity analysis excluding 1 study at a time confirmed in direction and magnitude of statistical significance the results concerning BNP and NYHA functional class. Nevertheless, we found that the beneficial effect of statin treatment on LVEF turned to be vague (WMD: 2.62%, 95% CI: 0.08–5.33, P = 0.06) when the study by Yamada et al19 was omitted. Likewise, the impact of statin treatment on LVEDD and LVESD vanished simultaneously when studies conducted by either Sola et al13 (LVEDD—WMD: −2.30 mm, 95% CI: −5.22 to 0.62 mm, P = 0.12; LVESD—WMD: −2.88 mm, 95% CI: −7.33 to 1.57 mm, P = 0.20) or Wojnicz et al17 (LVEDD—WMD: −3.17 mm, 95% CI: −7.92 to 1.59 mm, P = 0.19; LVESD—WMD: −2.74 mm, 95% CI: −6.72 to 1.24 mm, P = 0.18) were excluded, but the favorable tendency remained.

Publication Bias

Assessment of publication bias using Egger's and Begg's tests showed that no potential publication bias existed among the included trials (Egger's test: P = 0.14; Begg's test: P = 0.47) (Supporting Figure 1A, 1B).

Discussion

We performed this meta‐analysis of 11 RCTs to determine the beneficial effects of statin treatment in patients with CHF. Interestingly, the results showed that in CHF patients, statin treatment significantly increases LVEF as compared with control. Moreover, its beneficial effects were further demonstrated by decreasing LVEDD, LVESD, BNP, and NYHA functional class. For assurance, we performed Egger's and Begg's tests to exclude the influence of publication bias on overall analyses.

Contrary to many earlier studies, 2 large‐scale randomized controlled trials, Controlled Rosuvastatin in Multinational Trial in Heart Failure (CORONA) and Effect of Rosuvastatin in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (GISSI‐HF), failed to show the expected benefits of statin treatment in patients with CHF21., 22.; nevertheless, 2 subsequent post hoc analyses for the CORONA study, which were inconsistent with our findings, inversely confirmed the potential benefits of statin treatment in a proportion of the patients with CHF (patients with high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein ≥2.0 mg/L, or plasma amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide<868 pg/mL).23., 24. That is to say, the benefits of statin treatment in patients with CHF cannot yet be completely denied.

The well‐established benefits of statins are thought to be mediated through their lipid‐lowering properties that decelerate the progression of the underlying cardiovascular diseases, such as decreasing the incidence of CHF in hyperlipidemic patients and reducing subsequent ischemic cardiac events.25 However, we should note that most of the subjects enrolled in our meta‐analysis had normal levels of low‐density lipoprotein9., 10., 11., 13., 14., 15., 19.; the aforementioned benefits of statins in CHF patients might, therefore, be accounted for by many other favorable pleiotropic effects. Currently, multiple studies have revealed that statins can decrease vascular and myocardial oxidative stress, facilitate nitric oxide synthesis and improve endothelial function, along with reducing markers of inflammation and cytokine activation,26., 27., 28., 29. all of which are thought to be important in mediating the progression of heart failure.28., 30., 31. In addition, statins possess antihypertrophic and antifibrotic effects that would also be expected to benefit cardiac remodeling and cardiac function and thereby ameliorate clinical symptoms represented by NYHA functional class.26., 32., 33. Specifically, it is possible that statins improve cardiac function in patients with CHF partially by exerting inhibitory effects on matrix metalloproteinases.34., 35. Thus, combining these findings with the fact that the change of BNP level is negatively related to the alteration of cardiac structure and function,36., 37. it seems plausible that statins can, as well, down‐regulate the blood level of BNP, which provides powerful prognostic information in patients with CHF.38

Because the beneficial effects of statin treatment in CHF patients were accompanied by significant heterogeneity in this pooled analysis, we performed plenty of meta‐regression analyses to explore potential sources. The results showed that, unlike publication year, mean age, sex, etiology of CHF, and baseline LVEF, follow‐up duration was significantly associated with LVEF improvement, whereas longer treatment intervals tended to yield more clinical benefits. In other words, the difference in follow‐up duration might be an origin of the interstudy discrepancy regarding the clinical outcome of LVEF. Because of the existing relationship between follow‐up duration and LVEF, it is not difficult to understand the equivocal results in sensitivity analyses. For instance, the study by Yamada19 had a much longer follow‐up of 31 months, as compared with an average of 8.4 months follow‐up in this meta‐analysis; thus, the beneficial effects of statin treatment are likely to be concealed by omitting this study from the overall analysis.

Besides follow‐up duration, another possible contributor to the conflicting results among the included studies could have been the utilization of different statins. Previous studies have verified the drug‐specific effects of statins.39., 40. Similarly, we noticed that only 1 study10 in this meta‐analysis focused on rosuvastatin treatment in CHF patients, and it failed to show any beneficial effects on cardiac function and remodeling; whereas other enrolled studies9., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19. that targeted atorvastatin, cerivastatin, or simvastatin have brought about relatively better outcomes. This suggests that statins may not be acting as a “class,” at least in patients with CHF.

As with many other meta‐analyses, this study has several limitations. It is worth noting that, although 11 RCTs were included in this meta‐analysis, these trials were relatively small, with only 590 subjects in all; also, the enrolled studies had wide‐ranging follow‐up duration. Both of these factors may result in unreliable outcomes. In addition, even though the findings from this meta‐analysis are highly suggestive, we have not yet determined whether additional use of statins would reduce mortality in patients with CHF.

Conclusion

This meta‐analysis showed that statin treatment might confer benefits not only in increasing LVEF, but also in reducing LVEDD, LVESD, BNP, and NYHA functional class in CHF patients. Moreover, the improvement of LVEF associated with statin treatment might be time‐dependent, suggesting that statin therapy may be a potential novel treatment strategy for CHF patients.

References

- 1. Belch JJ, Bridges AB, Scott N, et al. Oxygen free radicals and congestive heart failure. Br Heart J 1991. 65 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003. 107 1486–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Packer M. Neurohormonal interactions and adaptations in congestive heart failure. Circulation 1988. 77 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trochu JN, Mital S, Zhang X, et al. Preservation of NO production by statins in the treatment of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2003. 60 250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mozaffarian D, Minami E, Letterer RA, et al. The effects of atorvastatin (10 mg) on systemic inflammation in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2005. 96 1699–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pliquett RU, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Statin therapy restores sympathovagal balance in experimental heart failure. J Appl Physiol 2003. 95 700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayashidani S, Tsutsui H, Shiomi T, et al. Fluvastatin, a 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor, attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002. 105 868–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauersachs J, Galuppo P, Fraccarollo D, et al. Improvement of left ventricular remodeling and function by hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibition with cerivastatin in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001. 104 982–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bleske BE, Nicklas JM, Bard RL, et al. Neutral effect on markers of heart failure, inflammation, endothelial activation and function, and vagal tone after high‐dose HMG‐CoA reductase inhibition in non‐diabetic patients with non‐ischemic cardiomyopathy and average low‐density lipoprotein level. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006. 47 338–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krum H, Ashton E, Reid C, et al. Double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of high‐dose HMG CoA reductase inhibitor therapy on ventricular remodeling, pro‐inflammatory cytokines and neurohormonal parameters in patients with chronic systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 2007. 13 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laufs U, Wassmann S, Schackmann S, et al. Beneficial effects of statins in patients with non‐ischemic heart failure. Z Kardiol 2004. 93 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Node K, Fujita M, Kitakaze M, et al. Short‐term statin therapy improves cardiac function and symptoms in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2003. 108 839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sola S, Mir MQ, Lerakis S, et al. Atorvastatin improves left ventricular systolic function and serum markers of inflammation in nonischemic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006. 47 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strey CH, Young JM, Lainchbury JH, et al. Short‐term statin treatment improves endothelial function and neurohormonal imbalance in normocholesterolaemic patients with non‐ischaemic heart failure. Heart 2006. 92 1603–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tousoulis D, Antoniades C, Vassiliadou C, et al. Effects of combined administration of low dose atorvastatin and vitamin E on inflammatory markers and endothelial function in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005. 7 1126–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vrtovec B, Okrajsek R, Golicnik A, et al. Atorvastatin therapy increases heart rate variability, decreases QT variability, and shortens QTc interval duration in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2005. 11 684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wojnicz R, Wilczek K, Nowalany‐Kozielska E, et al. Usefulness of atorvastatin in patients with heart failure due to inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy and elevated cholesterol levels. Am J Cardiol 2006. 97 899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xie RQ, Cui W, Liu F, et al. Statin therapy shortens QTc, QTcd, and improves cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2010. 140 255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamada T, Node K, Mine T, et al. Long‐term effect of atorvastatin on neurohumoral activation and cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure: a prospective randomized controlled study. Am Heart J 2007. 153 1055.e1–1055e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smetanina IN, Vaulin NA, Masenko VP, et al. Short term simvastatin use in patients with heart failure of ischemic origin: changes of blood lipids, markers of inflammation and left ventricular function [in Russian]. Kardiologiia 2006. 46 44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kjekshus J, Apetrei E, Barrios V, et al. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2007. 357 2248–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gissi‐HF Investigators, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI‐HF trial): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 2008. 372 1231–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McMurray JJV, Kjekshus J, Gullestad L, et al. Effects of statin therapy according to plasma high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein concentration in the Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure (CORONA): a retrospective analysis. Circulation 2009. 120 2188–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cleland JGF, McMurray JJV, Kjekshus J, et al. Plasma concentration of amino‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide in chronic heart failure: prediction of cardiovascular events and interaction with the effects of rosuvastatin: a report from CORONA (Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2009. 54 1850–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Berg K, et al. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) 1994. Atheroscler Suppl 2004. 5 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takemoto M, Node K, Nakagami H, et al. Statins as antioxidant therapy for preventing cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 2001. 108 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feron O, Dessy C, Desager JP, et al. Hydroxy‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A reductase inhibition promotes endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation through a decrease in caveolin abundance. Circulation 2001. 103 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drexler H, Hornig B. Endothelial dysfunction in human disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1999. 31 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lefer DJ. Statins as potent anti‐inflammatory drugs. Circulation 2002. 106 2041–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, et al. Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1990. 323 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wiedermann CJ, Beimpold H, Herold M, et al. Increased levels of serum neopterin and decreased production of neutrophil superoxide anions in chronic heart failure with elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993. 22 1897–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel R, Nagueh SF, Tsybouleva N, et al. Simvastatin induces regression of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improves cardiac function in a transgenic rabbit model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001. 104 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin J, Denver R, Bailey M, et al. In vitro inhibitory effects of atorvastatin on cardiac fibroblasts: implications for ventricular remodelling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2005. 32 697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, et al. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase‐9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 2000. 106 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Sugiyama S, et al. An HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation 2001. 103 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Mechanisms of disease: natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med 1998. 339 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uusimaa P, Tokola H, Ylitalo A, et al. Plasma B‐type natriuretic peptide reflects left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic function in hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2004. 97 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anand IS, Fisher LD, Chiang YT, et al. Changes in brain natriuretic peptide and norepinephrine over time and mortality and morbidity in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val‐HeFT). Circulation 2003. 107 1278–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goldstein MR. Effects of lovastatin and pravastatin on coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med 1994. 120 811–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tonkin AM. Management of the Long‐Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) study after the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Am J Cardiol 1995. 76 107C–112C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]