Abstract

Technical and pharmacologic advances have reduced the occurrence of large periprocedural myocardial infarction (PMI) after percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), but PMI still occurs in 6% to 18% of the cases and is associated with impaired short‐ and long‐term survival. PMI might be due to side branch closure or flow‐limiting dissection, but is most often diagnosed after apparently uncomplicated PCI and is due to atheroembolization into the microcirculation. Various definitions of PMI are used in clinical trials, but a rise in creatine kinase‐MB greater than 3 to 8 times the upper limit of normal is consistently associated with worse prognosis, particularly as it reflects a more extensive and unstable atherosclerotic burden. On the other hand, data regarding the independent prognostic value of periprocedural troponin increase are conflicting. Some data suggest that PMI has a better prognosis than a spontaneously occurring myocardial infarction, and that its incidence is reduced with aggressive antiplatelet and statin therapy. Copyright © 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Introduction

In the current era of antiplatelet therapy and routine stenting, acute ischemic complications occurring following percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) have been reduced. However, the periprocedural increase in cardiac biomarkers continues to occur in a substantial proportion of patients.

Definition of Periprocedural Myocardial Infarction

The definition of periprocedural myocardial infarction (PMI) is a matter of debate and varies between clinical trials. The consensus definition of myocardial infarction (MI) published in 2000 initially defined MI, including PMI, as any rise and fall in cardiac biomarkers (creatine kinase‐MB fraction [CK‐MB] or troponin) above the upper limit of normal (ULN).1 Later in 2007, the universal definition of MI adopted by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) defined PCI‐related myocardial infarction as an increase of biomarkers (CK‐MB or troponin) greater than 3 times ULN, and considered elevations of cardiac biomarkers between 1 and 3 times ULN as indicative of periprocedural myocardial necrosis but not infarction.2 An isolated rise in troponin above 3 times ULN was considered enough to define PMI. As opposed to the general definition of MI that mandates the additional presence of symptoms or electrocardiographic or imaging abnormalities suggestive of ischemia, an isolated rise in cardiac biomarkers is enough to define PMI.

This definition applies for patients with normal baseline biomarkers. If the biomarkers values are abnormal and rising prior to PCI, the above document acknowledges that there are insufficient data to recommend biomarker criteria for the diagnosis of PMI. If the biomarkers' values are stable or falling, recurrent infarction is diagnosed in case of ≥ 20% increase of a previously downward trending troponin or CK‐MB value.2

Recent clinical trials have adopted this definition of PMI with some modifications. In the Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY (ACUITY), Early Glycoprotein IIb‐IIIa Inhibition in Non‐ST‐Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome (EARLY ACS), and Timing of Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome (TIMACS) trials, when baseline CK‐MB values prior to PCI were normal or were elevated but falling, PMI was defined as new Q waves or as CK‐MB greater than 3 times ULN within 24 hours of PCI along with an increase of 50% above the most recent pre‐PCI level.3, 4, 5 In patients presenting with elevated CK‐MB that was rising and who had PCI within 24 hours of presentation, the occurrence of prolonged ischemic symptoms ≥ 30 minutes or new ischemic ST abnormalities or Q waves after PCI, along with an increase of the next CK‐MB by at least 50%, defined PMI. Troponin was not used to define PMI, but its use was allowed in TIMACS and EARLY ACS trials if CK‐MB data were unavailable.3, 4, 5

Periprocedural MI and spontaneous MI unrelated to PCI (typically due to atherosclerotic plaque rupture) are often equated as outcome measures in clinical trials, including the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial.6 The validity of this practice is questionable as the mechanisms of PMI and spontaneous MI are different, the long‐term prognosis is potentially different, and the definition of PMI is inconsistent across trials.

Incidence

The incidence (3.6%–48.8%) and magnitude of myocardial damage after PCI is highly variable, depending on the patient's presentation (acute coronary syndrome [ACS] vs stable coronary artery disease [CAD]), the angiographic and procedural characteristics, the adjunctive pharmacotherapy, and the biomarker and thresholds applied to detect its presence.7,8 On average, 23% of patients have an increase in CK‐MB above ULN after PCI, with most elevations being 1 to 3 times ULN, and 27% of patients have an increase in troponin I.7 CK‐MB rises to greater than 3 times ULN after 6% to 18% of PCIs.8, 9, 10 In the ACUITY trial, PMI occurred in 6% of patients with ACS undergoing PCI; this included a periprocedural Q‐wave MI in 1% of the patients.8 The incidence of Q‐wave MI has been reduced in the current era of stenting and use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists from a historical incidence of 2.1% to 0.8%.11

The PCI guidelines published by the ACC in 2005 give a class IIa recommendation for routine measurement of CK‐MB and troponin 8 to 12 hours after PCI in all patients regardless of symptoms, for prognostic evaluation.12

Prognostic Value of PMI

Prognostic Value of CK‐MB Elevation

Stone et al10 studied 7147 patients with systematically collected CK‐MB after elective PCI. CK‐MB increased to greater than 3 times ULN in 18% of patients, and Q‐wave MI developed in 0.6% of patients. By multivariate analysis, the periprocedural development of new Q waves was the most powerful independent determinant of in‐hospital and long‐term death (2‐year mortality rate, 38.3%; hazard ratio, 9.9; P < 0.0001). Non–Q‐wave MI with CK‐MB greater than 8 times ULN was also a strong predictor of death (2‐year mortality rate, 16.3%; hazard ratio, 2.2; P < 0.0001); in‐hospital and long‐term survival were unaffected by lesser degrees of CK‐MB elevation. Another study suggested that only striking increases of CK‐MB to greater than 10 times ULN are associated with an increased risk of 3‐year mortality.13 Such patients should probably be considered to have MI in the traditional sense and be treated accordingly.

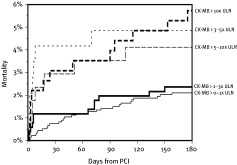

Smaller increases in CK‐MB have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of death in 2 meta‐analyses.14,15 The adjusted mortality risk at 6 months was not significantly increased for CK‐MB values of 1 to 3 times ULN, but was increased for CK‐MB values of 3 to 5 times ULN (RR, 2.82; P = 0.03), 5 to 10 times ULN, and greater than 10 times ULN (unadjusted increase in mortality is shown in Figure 1).14 There was a dose‐response relationship between the degree of CK‐MB increase and the risk of death.15

Figure 1.

Unadjusted mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) through 6 months for increments of periprocedural peak creatine kinase (CK)‐ MB elevation as a multiple of the upper limit of normal (ULN). Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.14

Recently, a concern was raised about the validity of CK‐MB data in various geographic centers. In fact, in the Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxaparin, Revascularisation, and GlYcoprotein Inhibitors trial, only moderate agreement between the site‐measured CK‐MB ratio and the corresponding core laboratory ratio was observed. Thus, in international multicenter clinical trials, MI definition seems to vary according to the study site, possibly limiting the validity of the MI end point.16

Prognostic Value of Troponin Elevation

Several studies have addressed the prognostic value of periprocedural troponin increase. One recent analysis from Cornell Angioplasty Registry showed that after elective PCI, troponin I elevation without CK‐MB elevation occurs very commonly and is not associated with any increase of a very low short‐term (in‐hospital) mortality, regardless of the degree of troponin elevation; however, troponin I levels greater than 5 times ULN were independently associated with a 1.8‐fold increase of long‐term (2‐year) mortality.17 A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showed a strong and linear correlation between troponin increase and irreversible myocardial injury.18 On the other hand, most older studies do not show an association between troponin elevation after PCI and long‐term mortality.19, 20, 21 The large prospective CK‐MB and PCI study indicated a linear relationship between postprocedural CK‐MB elevation and 2‐year mortality, but failed to confirm a prognostic merit for postprocedural troponin I elevation.22 Although an initial analysis from the Mayo Clinic registry found a modest increase in the long‐term risk of cardiovascular events with any degree of isolated troponin elevation, a later analysis did not find an independent long‐term prognostic value of postprocedural troponin. These variable findings might be due to different cutoffs used to define troponin elevation and to the variable inclusion of patients with mild preprocedural troponin elevation, a prognostic marker that is much more powerful than postprocedural troponin elevation.23,24

Thus, it seems that periprocedural MI is an independent predictor of death mainly in cases of a Q wave MI or a large non‐Q wave MI, the definition of which varies (greater than 3–8 times ULN). In line with the current guidelines, it seems reasonable to consider postprocedural CK‐MB elevations greater than 3 times ULN as clinically relevant. Despite being adopted by the guidelines as an arbitrary convention for PMI definition,2 the prognostic value of troponin elevation is less evident.

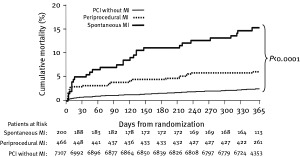

Spontaneous MI vs Periprocedural MI

A substudy of the ACUITY trial addressed the different prognostic value of spontaneously occurring MI and periprocedural MI, events that are usually considered together in clinical trials. As compared with patients without MI, PMI as defined by the ACUITY trial was associated with increased mortality at 1 year (6% vs 2.6%; P < 0.0001); however, a spontaneous MI occurring later than 24 hours after PCI was associated with a much larger increase in the one year mortality (16% vs 2.6%, P < 0.0001).8 Multivariate analysis showed that spontaneously occurring MI was the strongest independent predictor of subsequent mortality within the following year (hazard ratio: 7.49, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2). In contrast, PMI as a group was not independently related to subsequent mortality (hazard ratio: 1.30, P = 0.22). This is potentially related to the lower threshold of CK‐MB used to define PMI (greater than 3 times ULN), which is lower than the prognostic threshold identified by Stone et al.10 Q wave MI, on the other hand, was associated with a striking increase in mortality at 1 year whether it occurred spontaneously or after PCI (27% and 17.3%, respectively; P = 0.22). The authors concluded that periprocedural MI is a marker of clinical syndrome acuity, atherosclerotic plaque burden, and procedural complexity, and although increases in periprocedural cardiac enzyme do represent myonecrosis, in most cases the level of myocardial damage is below the threshold that independently increases short‐term or late mortality. Based on the prognostic values of various patterns of postprocedural myocardial necrosis, we suggest a prognostic classification of postprocedural myocardial necrosis (Table 1).

Figure 2.

One‐year death among all patients in the ACUITY trial according to the presence or absence of periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) or spontaneous MI. Abbreviations: PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press.8

Table 1.

Classification of Myocardial Necrosis Occurring After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

| Types | Definition | Nomenclature | Independent Association With Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isolated troponin increase or troponin increase with CK‐MB 1– 3 times ULN | Infarctlet or necrosette | Uncertain |

| 2 | CK‐MB 3– 8 times ULN | Moderate PMI | Moderate association that increases linearly with the degree of CK‐MB rise |

| 3 | CK‐MB >8 times ULN with no Q waves | Large non– Q‐wave PMI | Strong |

| 4 | New Q waves in ≥2 contiguous leads | Q‐wave PMI | Very strong |

| 5 | Stent thrombosisa | Stent thrombosis | Very strong |

| 6 | Spontaneous MI occurring >24 hours after PCIb | Spontaneous MI | Very strong |

Abbreviations: CK‐MB, creatine kinase‐MB fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PMI, periprocedural myocardial infarction; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Stent thrombosis is definite in cases of angiographic or pathologic confirmation, and probable in cases of unexplained death within 30 days of stenting.

As opposed to periprocedural myocardial necrosis type 6, myocardial necrosis types 1 to 4 occur within 24 hours of PCI. Spontaneous MI is defined according to the general definition of myocardial infarction, (ie, an increase in biomarkers above the upper limit of normal associated with ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic or imaging changes suggestive of ischemia)

Prognostic Value of Periprocedural Chest Pain

Periprocedural chest pain is common and occurs in 23% to 41% of patients after stenting.25 It is usually not associated with PMI or electrocardiographic changes and is thought to be nonischemic in origin and related to a continuous stretch of the treated vessel segment by the deployed stent,25 which can also lead to vasoconstriction via cardio‐cardiac reflex pathways.7 Other studies have, however, shown that postprocedural elevations of CK‐MB are 2.5 to 4 times more common among patients with postprocedural chest pain, more so if associated with ST‐T changes or with a clearly identified procedural complication.26 Yet most PMIs are clinically silent.7

Mechanisms of Periprocedural MI and Risk Factors

Q‐wave MI and large non–Q‐wave MI are usually related to angiographically documented complications during PCI, such as flow‐limiting dissection, abrupt vessel closure that is not promptly treated, branch vessel occlusion, or macroscopic embolization (Table 2).7 Most PMI are, however, diagnosed after apparently uncomplicated PCIs. In these cases without clear evidence of angiographic complications, intravascular ultrasound studies have shown a close correlation between the amount of atherosclerotic plaque burden and PMI, pointing toward the significance of atheroembolization in the pathophysiology of PMI.27 In addition, plaque disruption releases prothrombotic biofactors into the coronary circulation, leading to microvascular thrombosis, platelet activation, microcirculatory inflammation and oxidative stress, and no‐reflow phenomenon.28 Patients with multivessel disease, multiple or long lesions, or diffusely diseased arteries have a larger atherosclerotic burden and are more prone to PMI. Also, complex lesions requiring complex PCI predispose to PMI.7 Saphenous venous graft (SVG) lesions carry a high risk of PMI (ie, CK‐MB greater than 3 times ULN), as high as 15%, related to the increased incidence of micro‐ and macroembolization, particularly in grafts older than 3 years.29,30 This incidence is reduced by ∼50% with the use of embolic protection devices.29

Table 2.

Mechanisms of Periprocedural Myocardial Infarction

| Q‐wave MI or large non– Q‐wave MI |

| Abrupt vessel closure that is not promptly treated |

| Flow‐limiting dissection |

| Side branch occlusion or side branch flow impairmenta |

| Macroembolization |

| Small or moderate non– Q‐wave MI |

| Microembolization of atherosclerotic debris, microvascular spasm and microvascular thrombib |

| Epicardial vasospasm |

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

May be seen with bifurcation interventions, with overlapping Taxus stents, or with stenting long segments.

Patients with a large atherosclerotic burden, diffusely diseased coronary arteries, complex lesions requiring complex PCI, and SVG interventions are at higher risk of periprocedural MI

Side branch flow impairment or occlusion during bifurcation intervention is associated with a 1.7‐ to 7.9‐fold increased risk of PMI.7 Intriguing observations from TAXUS V and TAXUS VI studies suggest that the use of overlapping paclitaxel‐eluting stents (Taxus; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) is associated with an increased incidence of 30‐day MI (8.3% vs 3.3%; P = 0.047). Angiographic analysis of these patients showed a higher incidence of side branch compromise with overlapping Taxus stents than with overlapping bare‐metal stents despite similar stent backbone, raising concerns about the thickness of the Taxus polymer and about coronary spasms induced by paclitaxel or by the Taxus polymer.31,32 Although placement of overlapping sirolimus‐eluting stents was associated with PMI and side branch compromise in one registry,33 this association was not observed when overlapping sirolimus‐eluting stents were compared with overlapping bare‐metal stents.34 Stented segment length per se was associated with PMI, rather than stent type. Thus, stent length, stent overlap, and the Taxus design are associated with increased risk of branch vessel compromise.

Mechanisms of the Relation Between PMI and Long‐term Mortality

A marked increase in biomarkers after PCI (ie, CK‐MB greater than 5 to 8 times ULN) indicates some degree of myocardial damage that has been confirmed by MRI studies.18 These studies have shown that irreversible myocardial injury occurred in ∼30% of patients after complex or multivessel PCI, despite the use of preloaded clopidogrel and abciximab in all patients. The scar size represented, on average, 5% of the total LV mass, but involuted to a smaller volume of ∼3.5% at 6 months of follow‐up. There was a striking correlation between the troponin I rise after the procedure and the magnitude of MRI‐defined irreversible injury, which implies that troponin elevation in the setting of PCI represents true myocardial cell death, rather than troponin leak without cellular necrosis. This injury might affect left ventricular function and promote arrhythmias. In fact, there is an increase in the magnitude of risk for PMI in cases of baseline LV systolic dysfunction or incomplete revascularization.35

In addition, the increase in biomarkers reflects a more extensive and unstable atherosclerotic burden that predisposes to future ischemic events. The latter is likely the main reason for survival impairment, thus explaining that the unadjusted increase in mortality is more striking than the adjusted increase in mortality related to PMI.14,21

Prevention of Periprocedural Myocardial Infarction

Antiplatelet Therapies

In the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial, a clopidogrel loading dose of 300 mg ≥ 15 hours before elective PCI reduced 30‐day major adverse events, particularly early MIs.36 In the PCI‐Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (PCI‐CURE) trial, clopidogrel therapy prior to PCI reduced the incidence of early MI by more than 50% in patients with ACS.37 In the Antiplatelet Therapy for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty‐2 (ARMYDA‐2) trial, a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel administered 4 to 8 hours before PCI reduced PMI by ∼50% in comparison to a 300 mg dose.38

In the Evaluation of Platelet IIb/IIIa Inhibitor for Stenting (EPISTENT) and the Enhanced Suppression of the Platelet IIb/IIIa Receptor with Integrilin Therapy (ESPRIT) trials, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists reduced the 30‐day risk of MI by ∼50%, partly through a reduction of PMI.9,39 The combination of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists and clopidogrel further reduced the risk of MI, particularly PMI, in patients with high‐risk ACS (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 2 [ISAR‐REACT 2] trial).40 In patients with stable CAD adequately preloaded with clopidogrel, the addition of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists reduced the risk of PMI in the Clopidogrel Loading With Eptifibatide to Arrest the Reactivity of Platelets‐2 (CLEAR‐PLATELETS‐2) study,41 but not in the larger ISAR‐REACT trial.42 The benefit of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists in the high‐risk SVG interventions is however questionable. An analysis of pooled data from 5 large trials failed to show any benefit from glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists in SVG interventions.43 This is likely due to the excessive atheroembolic and thrombotic burden encountered in degenerated SVGs.

Statin Therapy

In statin‐naïinodot;ve patients undergoing PCI for stable CAD or for ACS, a loading dose of 80 mg of atorvastatin (within 24 hours prior to PCI) reduced PMI by 50% to 66%.44,45 Also, in patients receiving chronic statin therapy, atorvastatin (loading dose of 80 mg given 12 hours before coronary angiography, with a 40‐mg dose given 2 hours before the procedure) further reduced PMI by 2.5‐fold.46 It seems that a single high dose of statin promptly modifies inflammatory responses, plaque stability, and thrombus formation, thus reducing PMI. Moreover, in a retrospective analysis of 803 patients undergoing rotablation, preprocedural statin use independently reduced PMI by 70%. Because rotablation is a unique model of plaque microembolization in humans, this analysis suggests that statins modify the atherosclerotic plaque and reduce the myocardial injury related to distal embolization and the oxidant‐induced mitochondrial dysfunction.47

Mechanical Approaches

In SVG interventions, distal embolic protection devices reduce PMI and 30‐day MI rate by ∼50%, with a trend toward lower 30‐day mortality (1.0% vs 2.3% in one trial, P = 0.17).29 However, these devices did not prove useful in acute MI related to native coronary disease48; thus, their only coronary application currently is SVG interventions. Proximal embolic protection might further reduce the incidence of MI in SVG interventions.49

Ischemic Preconditioning

The extent of myocardial necrosis after coronary occlusion is limited when preceded by a brief period of ischemia and subsequent reperfusion. Ischemia might be spontaneous or induced with a 90‐second balloon inflation during PCI, followed by a 5‐minute period of reperfusion, and then by a second 90‐second balloon inflation. This phenomenon is called ischemic preconditioning. In a randomized study of 150 patients undergoing PCI, Laskey demonstrated that ischemic preconditioning induced during PCI strikingly reduced postprocedural CK elevation by 70%, as compared to a single balloon inflation > 60 seconds or multiple inflations without intervening periods of reperfusion.50 In a subsequent large study, ischemic preconditioning was independently associated with reduced in‐hospital and 1‐year risk of death and MI.51 In addition, ischemic preconditioning not only offers local protection but might have a salutary effect on ischemia‐reperfusion injury of remote tissues as well.52 In fact, a strategy of inducing limb ischemia for remote ischemic preconditioning has shown a reduction in troponin release after PCI and in major adverse cardiac events at 6 months.53 This strategy was applied approximately one hour before angiography and consisted of cuff inflation to 200 mm Hg for 5 minutes over an upper arm, followed by 5 minutes of deflation to allow reperfusion; this was repeated 2 more times. Although additional studies are needed to assess the value of ischemic and remote ischemic preconditioning, the available data suggest a benefit of these relatively simple strategies.

Conclusion

Despite advances in antiplatelet therapies, PMI still occurs frequently, even after an apparently uncomplicated PCI, and is associated with impaired short‐ and long‐term survival, particularly when CK‐MB is greater than 3 to 8 times ULN. The role of troponin in the definition of PMI and the role of less marked CK‐MB elevations is controversial, but hopefully future research will provide further consensus on the entity of PMI. Consistent with the ACC guidelines,12 practical recommendations for the detection and management of PMI are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Practical Recommendations for the Prevention, Detection, and Management of PMI

| Prevention |

| Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, adequate clopidogrel preloading, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists if ACS or complicated PCI) |

| Statin therapy initiated before PCI |

| Embolic protection in SVG intervention |

| Ischemic preconditioning and remote ischemic preconditioning (possibly) |

| Diagnosis |

| Troponin and CK‐MB should be obtained after PCI in patients who have symptoms suggestive of MI and in those with complicated procedures (class I recommendation) |

| Routine measurement of these markers 8 to 12 hours after PCI is reasonable in all patients (class IIa recommendation) |

| Management |

| Intensive secondary prevention, including LDL goal <70 mg/dL (similar to spontaneous MI) |

| Post‐PCI angina associated with ischemic ECG changes or hemodynamic instability may dictate further interventional procedures depending on the amount of myocardium at risk and the likelihood of successful treatmenta |

| CK‐MB elevation >3– 5 times ULN may necessitate further in‐hospital observation, particularly in the presence of chest pain or ischemic electrocardiographic changes |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CK‐MB, creatine kinase‐MB fraction; GP, glycoprotein; ECG, electrocardiographic; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SVG, saphenous venous graft; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Elevated cardiac biomarkers per se do not dictate repeating coronary angiography

REFERENCES

- 1. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Expert Consensus Document. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2173–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stone GW, McLaurin BT, Cox DA, et al. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2203–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giugliano RP, White JA, Boden C, et al. Early versus delayed, provisional eptifibatide in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2176–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2165–2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boden WE, O' Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;35:1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herrmann J Peri‐procedural myocardial injury: 2005 update. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2493–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prasad A, Gersh BJ, Bertrand ME, et al. Prognostic significance of periprocedural versus spontaneously occurring myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes. An analysis from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The EPISTENT Investigators. Randomised placebo‐controlled and balloon angioplasty‐controlled trial to assess safety of coronary stenting with use of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade. Lancet 1998;352:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stone GW, Mehran R, Dangas G, et al. Differential impact on survival of electrocardiographic Q‐wave versus enzymatic myocardial infarction after percutaneous intervention: a device‐specific analysis of 7147 patients. Circulation 2001;104:642–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srinivas VS, Brooks MM, Detre KM, et al. Contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention versus balloon angioplasty for multivessel coronary artery disease: a comparison of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry and the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) study. Circulation 2002;106:1627–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2006;113:e166–e286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brenner SJ, Lytle BW, Schneider JP, et al. Association between CK‐MB elevation after percutaneous or surgical revascularization and three‐year mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:1961–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roe MT, Mahaffey KW, Kilaru R, et al. Creatine kinase‐MB elevation after percutaneous coronary intervention predicts adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2004;25:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ioannidis JPA, Karvouni E, Katritsis DG, et al. Mortality risk conferred by small elevations of creatine kinase‐MB isoenzyme after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1406–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linefsky JP, Lin M, Pieper KS, et al. Comparison of site‐reported and core laboratory‐reported creatine kinase‐MB values in non–ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (from the International Trial SYNERGY). Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1330–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feldman DN, Minutello RM, Bergman G, et al. Relation of troponin I levels following nonemergent percutaneous coronary intervention to short‐and long‐term outcomes. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1210–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Selvanayagam JB, Porto I, Channon K, et al. Troponin elevation after percutaneous coronary intervention directly represents the extent of irreversible myocardial injury: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2005;111:1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bertinchant JP, Polge A, Ledermann B, et al. Relation of minor cardiac troponin I elevation to late cardiac events after uncomplicated elective successful percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fuchs S, Kornowski R, Mehran R, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac troponin‐I levels following catheter‐based coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:1077–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cantor WJ, Newby LK, Christenson RH, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated troponin I after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1738–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cavallini C, Savonitto S, Violini R, et al. Impact of the elevation of biochemical markers of myocardial damage on long‐term mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the CK‐MB and PCI study. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1494–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prasad A, Rihal CS, Lennon RJ, et al. Significance of periprocedural myonecrosis on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis of preintervention and postintervention troponin T levels in 5487 patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2008;1:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prasad A, Singh M, Lerman A, et al. Isolated elevation in troponin T after percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with higher long‐term mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1765–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jeremias A, Kutscher S, Haude M, et al. Nonischemic chest pain induced by coronary interventions: a prospective study comparing coronary angioplasty and stent implantation. Circulation 1998;98:2656–2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kini AS, Lee P, Mitre CA, et al. Postprocedure chest pain after coronary stenting: implications on clinical restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mehran R, Dangas G, Mintz GS, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque burden and CK‐MB enzyme elevation after coronary interventions: intravascular ultrasound study of 2256 patients. Circulation 2000;101:604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mallat Z, Hugel B, Ohan J, et al. Shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in human atherosclerotic plaques: a role for apoptosis in plaque thrombogenicity. Circulation 1999;99:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baim DS, Wahr D, George B, et al; Saphenous Vein Graft Angioplasty Free of Emboli Randomized (SAFER) Trial Investigators. Randomized trial of a distal embolic protection device during percutaneous intervention of saphenous vein aorto‐coronary bypass grafts. Circulation 2002;105:1285–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong MK, Mehran R, Dangas G, et al. Creatine kinase‐MB enzyme elevation following successful saphenous vein graft intervention is associated with late mortality. Circulation 1999;100:2400–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cannon L, et al. Comparison of a polymer‐based paclitaxel‐eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dawkins KD, Grube E, Guagliumi G, et al. Taxus VI Investigators Clinical efficacy of polymer‐based paclitaxel‐eluting stents in the treatment of complex, long coronary artery lesions from a multicenter, randomized trial: support for the use of drug‐eluting stents in contemporary clinical practice. Circulation 2005;112:3306–3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chu WW, Kuchulakanti PK, Torguson R, et al. Impact of overlapping drug‐eluting stents in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2006;67:595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kereiakes D, Wang H, Popma JJ, et al. Periprocedural and late consequences of overlapping cypher sirolimus‐eluting stents. Pooled analysis of five clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ellis SG, Chew D, Chan A, et al. Death following creatine kinase‐MB elevation after coronary intervention: identification of an early risk period: importance of creatine kinase‐MB level, completeness of revascularization, ventricular function, and probable benefit of statin therapy. Circulation 2002;106:1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Brennan DM, et al. Optimal timing for the initiation of pre‐treatment with 300 mg clopidogrel before percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pre‐treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long‐term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI‐CURE Study. Lancet 2001;358:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patti G, Colonna G, Pasceri V, et al. Randomized trial of high loading dose of clopidogrel for reduction of periprocedural myocardial infarction in patients undergoing coronary intervention: results from the ARMYDA‐2 (Antiplatelet Therapy for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) study. Circulation 2005;112:2946–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The ESPRIT Investigators. Novel dosing regimen of eptifibatide in planned coronary stent implantation (ESPRIT): a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 2000;356:2037–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, et al. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR‐REACT 2 randomized trial. JAMA 2006;295:1531–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Saucedo JF, et al. Bivalirudin and clopidogrel with and without eptifibatide for elective stenting: effects on platelet function, thrombelastographic indexes, and their relation to periprocedural infarction results of the CLEAR PLATELETS‐2 (Clopidogrel With Eptifibatide to Arrest the Reactivity of Platelets) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Schuhlen H, et al; Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen‐Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR‐REACT) Study Investigators. A clinical trial of abciximab in elective percutaneous coronary intervention after pretreatment with clopidogrel. N Engl J Med 2004;350:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roffi M, Mukherjee D, Chew DP, et al. Lack of benefit from intravenous platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibition as adjunctive treatment for percutaneous interventions of aortocoronary bypass grafts: a pooled analysis of five randomized clinical trials. Circulation 2002;106:3063–3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brigori C, Visconti G, Focaccio A, et al. Novel Approaches for Preventing or Limiting Events (Naples) II trial: impact of a single high loading dose of atorvastatin on periprocedural myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2157–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patti G, Colonna G, Pasceri V, et al. Atorvastatin pretreatment improves outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing early percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA‐ACS randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Di Sciascio G, Patti G, Pasceri V, et al. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA‐RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gurm HS, Breibart Y, Vivekanathan D, et al. Preprocedural statin use is associated with a reduced hazard of postprocedural myonecrosis in patients undergoing rotational atherectomy—a propensityadjusted analysis. Am Heart J 2006;151:1031–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stone GW, Webb J, Cox DA, et al. Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. A randomized controlled trial (EMERALD trial). JAMA 2005;293:1063–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mauri L, Cox D, Hermiller J, et al. The PROXIMAL trial: proximal protection during saphenous vein graft intervention using the Proxis Embolic Protection System: a randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1442–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Laskey WK Beneficial impact of preconditioning during PTCA on creatine kinase release. Circulation 1999;99:2085–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Laskey WK, Beach D Frequency and clinical significance of ischemic preconditioning during percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1004–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kharbanda RK, Mortensen UM, White PA, et al. Transient limb ischemia induces remote ischemic preconditioning in vivo. Circulation 2002;106:2881–2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hoole SP, Heck PM, Sharples L, et al. Cardiac remote ischemic preconditioning in coronary stenting (CRISP Stent) study. Circulation 2009;119:820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]