Abstract

Aims: Autophagy is a catabolic process required for the maintenance of cardiac health. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) are potent inhibitors of autophagy and as such, one would predict that autophagy will be increased in the insulin-resistant/diabetic heart. However, autophagy is rather decreased in the hearts of diabetic/insulin-resistant mice. The aim of this study is to determine the contribution of IGF-1 receptor signaling to autophagy suppression in insulin receptor (IR)-deficient hearts.

Results: Absence of IRs in the heart was associated with reduced autophagic flux, and further inhibition of autophagosome clearance reduced survival, impaired contractile function, and enhanced myocyte loss. Contrary to the in vivo setting, isolated cardiomyocytes from IR-deficient hearts exhibited unrestrained autophagy in the absence of insulin, whereas addition of insulin was able to suppress autophagy. To investigate the mechanisms involved in the maintenance of the responsiveness to insulin in IR-deficient hearts, we generated mice lacking both IRs and one copy of the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) in cardiac cells and showed that these mice had increased autophagy.

Innovation and Conclusion: This study unveils a new mechanism by which IR-deficient hearts can still respond to insulin to suppress autophagy, in part, through activation of IGF-1R signaling. This is a highly significant observation because it is the first to show that systemic hyperinsulinemia can suppress autophagy in IR-deficient hearts through IGF-1R signaling.

Keywords: insulin, autophagy, contractile function, IGF-1 receptors, cardiomyocytes, hyperinsulinemia

Introduction

Diabetes is increasingly prevalent worldwide (1, 33) and is associated with high mortality and morbidity. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and people with diabetes have a twofold to fourfold increased risk for developing CVD compared with those without diabetes (9, 43). Indeed, the hearts of diabetic individuals exhibit more susceptibility to ischemic injury and an increased likelihood of congestive heart failure. The mechanisms underlying the high incidence of diabetic cardiac dysfunction remain relatively obscure but may include altered metabolism and mitochondrial function, enhanced oxidative stress, impaired calcium signaling, and altered macroautophagy (referred to herein as autophagy).

Innovation.

Studies involving the assessment of autophagy in insulin resistant type 2 diabetic hearts have been inconsistent. The present study provides evidence that systemic hyperinsulinemia can suppress autophagy in insulin receptors deficient hearts through insulin-like growth factor receptors signaling.

Autophagy is a conserved catabolic pathway in which long-lived and damaged proteins and organelles are delivered to and degraded by lysosomes (12). Autophagy is essential for the homeostatic function of the heart as its disruption caused heart failure in mice (36). However, studies examining the functional role of autophagy in the diabetic myocardium have been inconsistent. Thus, reduced autophagic flux was observed in the hearts of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetes and OVE26 diabetic mice and this decrease was rather protective because further attenuation of this process preserved cardiac function and reduced cardiac remodeling (13, 21, 42, 45, 47). Similarly, cardiac autophagic flux was reduced in mouse models of dietary and genetic obesity (4, 14, 18, 22, 26, 39, 41, 46, 48). However, other studies have reported an increase in cardiac autophagic markers in STZ mice and in mice fed a high-sucrose diet (19, 32, 38). Similarly, autophagic markers were elevated in atrial tissue from diabetic patients (34). The reasons behind these discrepant results may be due to different methods used for the assessment of autophagy (static vs. flux), the severity and duration of diabetes, and the presence or absence of obesity. Furthermore, the upstream signaling involved in autophagy regulation in the diabetic myocardium is not fully understood.

Growth factor signaling is a known inhibitor of autophagy (27). Thus, one would predict that in the setting of impaired insulin action or insulin resistance, a hallmark of the diabetic myocardium, autophagy would be increased. However, autophagy is rather decreased in the insulin-resistant heart. The goal of the present study is to assess the contribution of insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) signaling in the suppression of cardiac autophagy when insulin receptors (IRs) are deficient. We provide evidence that IR-deficient hearts exhibit reduced autophagic flux and are more susceptible to further inhibition of lysosomal function. This suppression of autophagic flux causes cardiac dysfunction and enhances cardiomyocyte death in mice lacking cardiac IRs. The significant finding of this study is that systemic hyperinsulinemia suppresses autophagy through IGF-1R signaling in IR-deficient hearts. This novel mechanism may explain the sustained suppression of cardiac autophagy and provide evidence for the protective effect of IGF-1R in restraining cardiac autophagy and cell death in insulin-deficient/resistant hearts.

Results

Insulin suppresses autophagy in H9c2 cells in vitro

Insulin is known to suppress autophagy in the liver and skeletal muscle (35), however, whether insulin has the same effect on cardiac autophagy is still not clear. To begin to understand the effect of insulin on cardiac autophagy, we first treated undifferentiated H9c2 rat myoblasts with insulin (100 nM) for 120 min and then assessed basal autophagy. Insulin treatment increased tyrosine phosphorylation of both IR and IGF-1R as well as the phosphorylation of their downstream targets protein kinase B (Akt) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) (Supplementary Fig. S1A–F). As expected, insulin treatment reduced basal autophagy as shown by the attenuation of LC3II and LC3I protein expression and the accumulation of the autophagy adaptor protein p62 (Supplementary Fig. S1A, G–K).

Decreased autophagic flux in TIRKO hearts

We previously showed that systemic hyperinsulinemia, in the setting of cardiac insulin resistance, was associated with reduced cardiac autophagic flux in obese type 2 diabetic (ob/ob) mice (39). To determine the relative contribution of IRs and IGF-1Rs in the suppression of cardiac autophagy by hyperinsulinemia, we used a mouse model that lacks IRs in the entire heart and exhibits systemic hyperinsulinemia. TIRKO (Ttr-Insr−/−) mice were engineered to rescue the lethality of whole-body IR knockout mice by overexpressing a human IR cDNA from the transthyretin promoter in the liver, brain, and beta-cells, respectively (37). TIRKO and wild-type (WT) mice had similar body weights (BWs) up to 12 weeks of age (24.6 ± 0.8 in TIRKO vs. 26.8 ± 0.4 in WT), but TIRKO hearts were smaller as evidenced by reduced heart weight/tibia length (0.06 ± 0.002 in TIRKO vs. 0.07 ± 0.003 in WT, *p < 0.05). TIRKO mice develop progressive hyperinsulinemia as a result of peripheral insulin resistance (mainly in skeletal muscle) but no diabetes. Although these mice do not represent a physiological condition, they are ideal for mechanistic investigations of IR signaling in the heart.

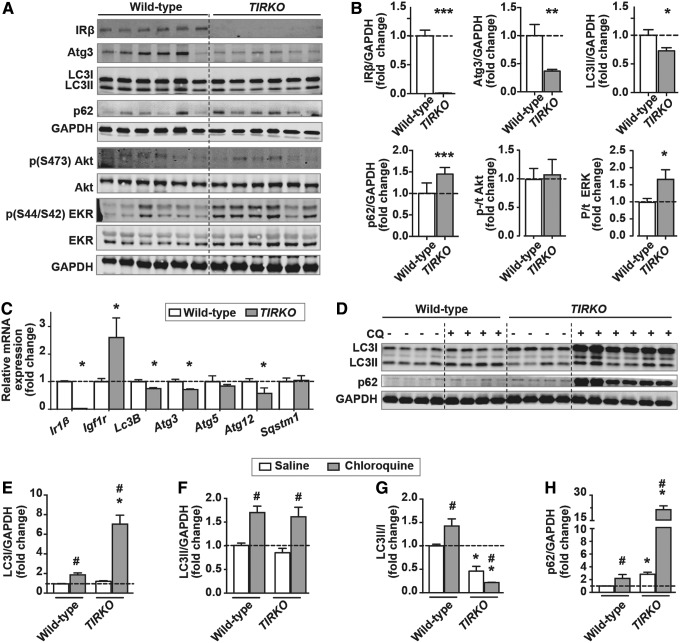

We confirmed the absence of IR mRNA and protein expression in TIRKO hearts (Fig. 1A–C). However, contrary to Ir1β mRNA expression, Igf-1r mRNA was rather increased in TIRKO hearts (Fig. 1C). We first hypothesized that lack of IRs in the heart will increase cardiac autophagy. In contrast, basal autophagy was rather diminished in TIRKO hearts as evidenced by the reduction in autophagy-related protein (Atg)3 and LC3II and the accumulation of p62 (Fig. 1A, B). Consistent with the reduction in basal autophagy, TIRKO hearts had lower mRNA expression of autophagy-related genes, including Lc3B, Atg3, and Atg12, whereas mRNA expression of Sqstm1 (p62) (sequestosome 1) was unchanged (Fig. 1C). To begin to understand the mechanisms behind this decline in basal autophagy, we first examined IR downstream targets' Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation and found an increase only in p/t ERK1/2 in TIRKO hearts (Fig. 1A, B).

FIG. 1.

Reduced cardiac autophagic flux in TIRKO mice. (A) Representative Western blots of IRβ, Atg3, LC3I and LC3II, p62/SQSTM1, phospho (S473) Akt, total Akt, phospho (S44/S42) ERK1/2, total ER1/2, and GAPDH in whole-heart homogenates from WT and TIRKO mice. (B) The corresponding densitometry of IR1β/GAPDH, Atg3/GAPDH, LC3II/GAPDH, p62/GAPDH, p/t Akt, and p/t ERK1/2 expressed as fold-change relative to WT. (C) Relative mRNA expression of Ir1β, Igf1r, Lc3b, Atg3, Atg5, Atg12, and sqstem1 in whole-heart homogenates from WT and TIRKO mice, expressed as fold-change relative to WT. (D) Representative Western blots of LC3I, LC3II, p62, and GAPDH in whole-heart homogenates from WT and TIRKO mice treated with saline or CQ for 4 h. (E–H) The corresponding densitometry of LC3I/GAPDH, LC3II/GAPDH, LC3II/LC3I, and p62/GAPDH expressed as fold-change relative to saline-treated WT mice. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 4–6 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.001 versus WT under the same treatment condition; #p < 0.05 versus saline within the same genotype. Akt, protein kinase B; Atg, autophagy related protein; CQ, chloroquine; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase; IRβ, insulin receptor β; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; SEM, standard error of the mean; SQSTM1 (p62), sequestome 1; TIRKO, Ttr-Insr−/−; WT, wild-type.

Reduced basal autophagy in TRKO hearts does not indicate that the autophagic flux is impaired. To directly measure autophagic flux, we treated TIRKO mice with the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) for 4 h before assessing autophagy. Treatment with CQ enhanced LC3I, LC3II, and p62 in WT hearts, but the increase in LC3II surpassed LC3I, thus enhancing the ratio of LC3II/LC3I (Fig. 1D–H). However, CQ led to a massive accumulation of LC3I and p62 and an equivalent increase in LC3II compared with WT, so that the ratio of LC3II/LC3I was significantly reduced in TIRKO hearts (Fig. 1D–H). These results suggest that TIRKO hearts have an impairment in LC3I conversion to LC3II at baseline and even more so when lysosomal function is inhibited by CQ. This is consistent with the significant reduction in Atg3 mRNA and protein expression, one of the key enzymes involved in LC3I lipidation to LC3II (7). Contrary to Atg3, protein expression of Atg7 or Atg5–12 was unchanged between WT and TIRKO hearts (data not shown).

Lysosomal inhibition caused cardiac dysfunction, myocyte loss, and reduced survival in TIRKO mice

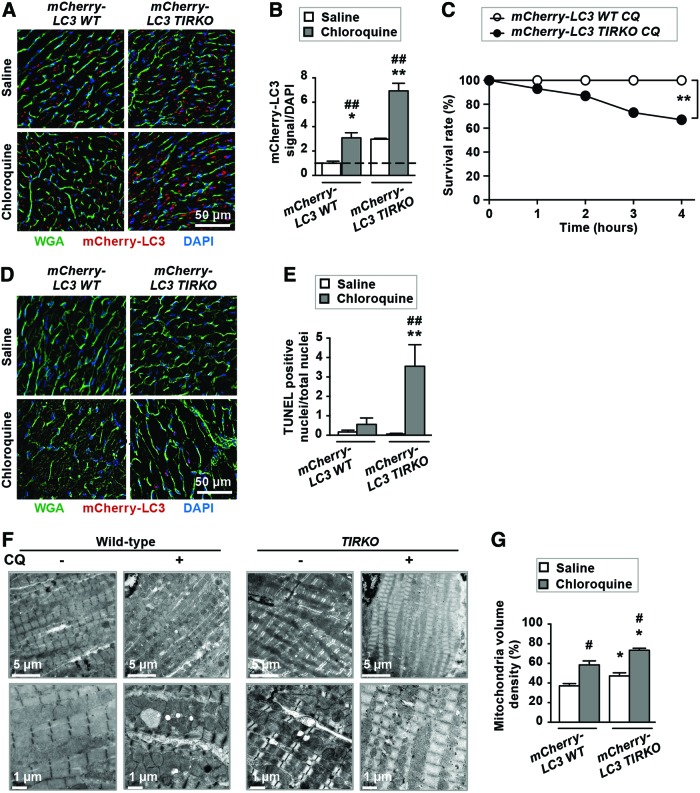

To further assess autophagic flux in vivo, we crossed TIRKO and WT mice with transgenic mice expressing the mCherry-microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) transgene under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter to confer cardiac specificity. The resulting mice referred to as mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice were treated with saline or CQ for 4 h before analyzing the number of mCherry-LC3-positive signals. Saline-treated mCherry-LC3 TIRKO transgenic mice had slightly more mCherry-LC3-positive signals in their hearts compared with saline-treated mCherry-LC3 WT mice (Fig. 2A, B). CQ treatment caused an equivalent threefold increase in mCherry-LC3 signal in both WT and TIRKO mice (Fig. 2A, B), suggesting that lysosomal function may be preserved in both genotypes. Due to the fact that mCherry-LC3 signals were elevated in saline-treated mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice, one may conclude that autophagosome formation is elevated. However, we believe that the mCherry-LC3 signal observed in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts is caused by the accumulation of both LC3I and LC3II aggregates. To further confirm that, we used triton x-100 extraction and we blotted for LC3I and II in the insoluble fraction. We detected both LC3I and LC3II in the insoluble fraction from both mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts (Supplementary Fig. S2D). However, mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts had more LC3I and LC3II at baseline and CQ further increased their amount in the insoluble fraction (Supplementary Fig. S2D).

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of lysosomal degradation reduced survival and enhanced cell death in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice. (A) Representative images of frozen heart sections from mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice treated with saline or CQ for 4 h. (B) Quantification of mCherry-LC3 signal per DAPI expressed as fold-change relative to saline-treated mCherry-LC3 WT mice. (C) Survival rate expressed in % of mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice treated with CQ for 4 h. (D) Representative images of frozen heart sections stained with TUNEL. (E) Quantification of TUNEL-positive nuclei/total nuclei. (F) Electron microscopy images of left ventricular tissue. (G) Quantification of mitochondrial volume density expressed as %. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 5–11 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus mCherry-LC3 WT under the same treatment condition; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 versus saline within the same genotype. Color images are available online.

Fasting is known to increase autophagy, and thus, we subjected mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice to 48-h fasting/starvation and assessed autophagy in the heart. This fasting protocol has been used in several studies involving cardiac autophagy (8, 10). As shown in Supplementary Figure S2A–C, mCherry-LC3 WT mice responded to fasting by increasing the number of mCherry-LC3 puncta by about eightfold compared with only a fourfold increase in autophagosome formation in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts. These results provide additional evidence for the impairment of cardiac autophagy in TIRKO mice.

To test if further inhibition of autophagic clearance in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice had functional consequences, we assessed survival and contractile parameters in saline- or CQ-treated mice. Post-CQ, all mCherry-LC3 WT mice (10 mice total) survived, whereas only 10 from a total of 15 mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice survived (Fig. 2C). This was associated with a 24% (*p < 0.05) reduction in ejection fraction (EF) in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice (Table 1). Furthermore, lysosomal inhibition significantly increased apoptotic cell death only in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts (Fig. 2D, E). Finally, we observed an accumulation of mitochondria post-CQ treatment in mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts, but the increase was more pronounced in the latter (Fig. 2F, G). The accumulation of mitochondria in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts was associated with fragmentation as supported by elevated phosphorylation (S637) and total dynamin-related protein 1 (Supplementary Fig. S2E–I). Altogether, these results demonstrated that autophagy is impaired and further attenuation of the autophagic clearance process can compromise contractile function and survival in mice lacking IRs in the heart.

Table 1.

Cardiac Dimension and Contractile Parameters in mCherry-LC3 Wild-Type and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO Mice Treated with Saline or Chloroquine for 2 h

| WT saline (n = 8) | WT CQ (n = 10) | TIRKO saline (n = 7) | TIRKO CQ (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.92 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 0.67 ± 0.06 |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.44 ± 0.09 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 1.06 ± 0.05 | 1.15 ± 0.18 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.53 ± 0.19 | 3.58 ± 0.09 | 3.77 ± 0.14 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.85 ± 0.21 | 2.18 ± 0.29 | 2.16 ± 0.12 | 2.78 ± 0.17 |

| EF (%) | 64.88 ± 3 | 59.6 ± 3.6 | 61.71 ± 1.8 | 47 ± 3.5* |

| FS (%) | 45.41 ± 5.05 | 39.05 ± 5.38 | 39.27 ± 2.41 | 26.34 ± 2.39 |

Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus wild type under the same treatment condition.

CQ, chloroquine; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; LVIDd, left ventricular interior diameter in diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular interior diameter in systole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall in diastole; LVPWs, left ventricular posterior wall in systole; TIRKO, Ttr-Insr−/−; WT, wild-type.

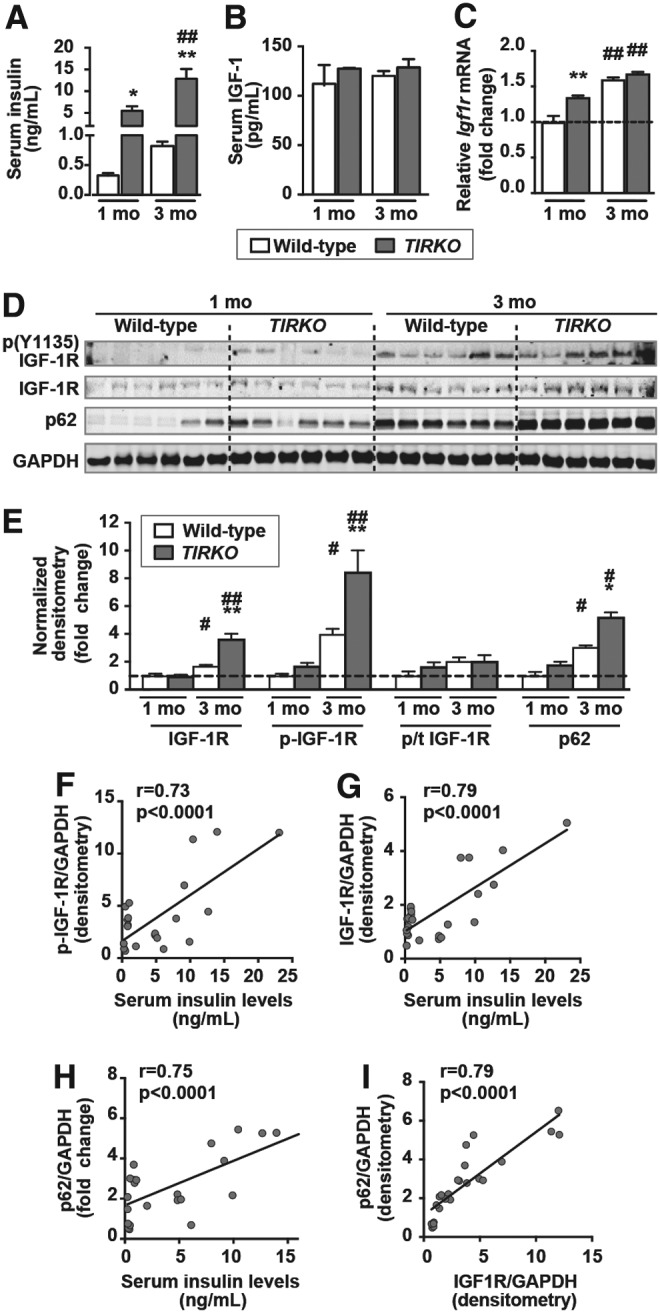

Systemic hyperinsulinemia correlates positively with IGF-1R activation and p62 accumulation in TIRKO hearts

We previously showed that systemic hyperinsulinemia was associated with enhanced cardiac IGF-1R signaling in (ob/ob) mice (39). TIRKO mice develop systemic hyperinsulinemia equivalent to that observed in (ob/ob) mice (Fig. 3A), but circulating insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels were similar to age-matched WT controls (Fig. 3B). TIRKO mice had higher mRNA expression of Igf1r mRNA at 1 month and by 3 months Igf1r mRNA similarly increased WT and TIRKO hearts (Fig. 3C). TIRKO hearts exhibited in higher protein expression and activation (phosphorylation at Y1135 residue) of IGF-1R at 3 months compared with age-matched WT controls (Fig. 3D, E). Interestingly, we found a significant positive correlation between cardiac IGF-1R (phosphorylated and total) and circulating insulin levels in TIRKO mice (Fig. 3F, G). It is worth noting that similar to IGF-1R, the p62 content also increased in TIRKO hearts and was positively correlated with both circulating insulin levels and IGF-1R content (Fig. 3D, E, H, and I). The increase in IGF-1R content in TIRKO hearts may constitute a compensatory mechanism for the lack of IRs. Indeed, mRNA level of Igf1r was more than twofold higher in TIRKO hearts compared with WT hearts (Fig. 1C). In contrast, p62 accumulation in TIRKO hearts is the result of autophagy inhibition because its mRNA expression was unaltered (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that systemic hyperinsulinemia may suppress autophagy in IR-deficient hearts.

FIG. 3.

IGF-1 receptor activation correlates positively with circulating insulin levels. (A, B) Random-fed serum insulin and IGF-1 levels, respectively, in 1- and 3-month-old WT and TIRKO mice. (C) Relative mRNA expression of Igf1r in WT and TIRKO hearts at 1 and 3 months, respectively. (D) Representative Western blots of phospho (Y1135) IGF-1R, total IGF-1R, p62, and GAPDH in whole-heart homogenates from WT and TIRKO mice at 1 and 4 months, respectively. (E) The corresponding densitometry of IGF-1R/GAPDH, p-IGF-1R/GAPDH, and p62/GAPDH expressed as fold-change relative to 1-month-old WT mice. (F–H) Correlation curves of serum insulin levels and normalized p-IGF-1R, IGF-1R, and p62 protein expression, respectively. (I) Correlation curve of normalized IGF-1R and p62 protein expression. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 6 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus age-matched WT; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 versus 1 month within the same genotype. IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor.

Hyperinsulinemia suppresses autophagy in TIRKO hearts

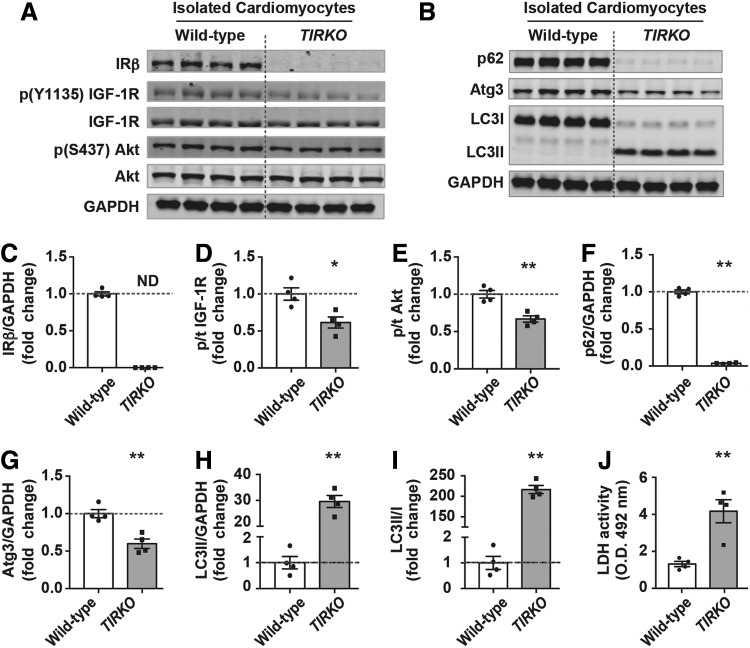

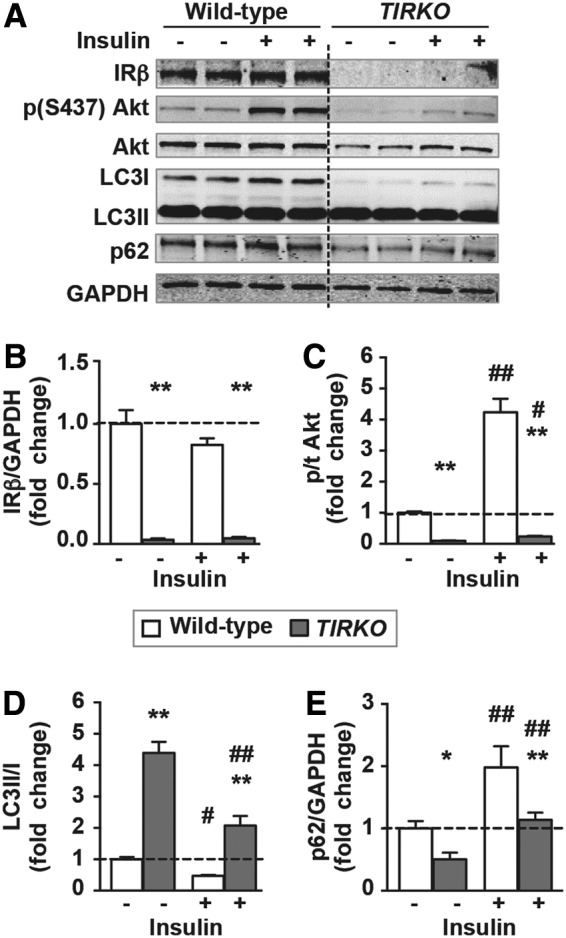

Due to the known suppressive effect of insulin on autophagy and because of the absence of IRs in TIRKO hearts, we hypothesized that systemic hyperinsulinemia may act through an IR-independent signaling pathway to suppress autophagy. Thus, to directly test that, we isolated cardiomyocytes from adult TIRKO and WT mice and cultured them for 2 h in the absence of insulin. We demonstrated that in the absence of insulin, cardiomyocytes from TIRKO hearts exhibited lower IGF-1R and Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4A–E). This reduction in IGF-1R/Akt signaling was associated with the induction of autophagy as shown by the increase in LC3II and the reduction in p62 (Fig. 4B, F–I). The induction of autophagy in cardiomyocytes from TIRKO hearts increased cell death as measured by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzymatic assay (Fig. 4J). These results demonstrate that lack of IRs in the heart caused an unrestrained autophagy that ultimately led to cell death when insulin was not present.

FIG. 4.

Increased autophagy and cell death of cardiomyocytes isolated from TIRKO hearts. (A, B) Representative Western blots of IRβ, phospho (Y1135) IGF-1R, total IGF-1R, phospho (S473) Akt, pan Akt, p62, Atg3, LC3I, LC3II, and GAPDH in homogenates from cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and TIRKO hearts. (C–I) The corresponding densitometry of IRβ/GAPDH, p-IGF-1R/total IGF-1R, p-Akt/total Akt, p62/GAPDH, Atg3/GAPDH, LC3II/GAPDH, and LC3II/LC3I expressed as fold-change relative to WT cells. (J) LDH activity in culture media. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 4 independent cardiomyocyte isolations. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus WT cells. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

To investigate if addition of insulin can inhibit autophagy in cardiomyocytes from TIRKO hearts, we treated these cells with insulin (100 nM) for 2 h before assessing autophagy. Insulin significantly reduced LC3II/I ratios and increased p62 levels in cardiomyocytes from TIRKO mice when compared with noninsulin-treated cells (Fig. 5A–E and Supplementary Fig. S3). Insulin induced an equivalent fourfold increase in IGF-1R phosphorylation in both WT and TIRKO cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B). Consistent with the suppressive effect of insulin on autophagy in H9c2 cells, cardiomyocytes from WT mice also responded to insulin by suppressing autophagy (lower LC3II/I ratios and increased p62 accumulation) (Fig. 5A–E). Interestingly, the inhibition of autophagy by insulin in WT cells was associated with a significant increase in Akt phosphorylation (Ser473), whereas this was attenuated in TIRKO cells (Fig. 5A–C). The question then is what upstream signaling is driving the suppression of autophagy by insulin in IR-deficient cells?

FIG. 5.

Insulin treatment of cardiomyocytes of TIRKO mice suppressed autophagy. (A) Representative Western blots of IRβ, phospho (S473) Akt, pan Akt, LC3I, LC3II, p62, and GAPDH in homogenates from WT or TIRKO cardiomyocytes treated with saline or insulin for 2 h. (B–E) The corresponding densitometry of IRβ/GAPDH, p-Akt/total Akt, LC3II/LC3I, and p62/GAPDH expressed as fold-change from WT cells treated with saline. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 4 independent cardiomyocyte isolations/treatment. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus WT cells and #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 versus (-insulin) within the same genotype.

Partial deletion of IGF-1R partially restored autophagy in TIRKO hearts

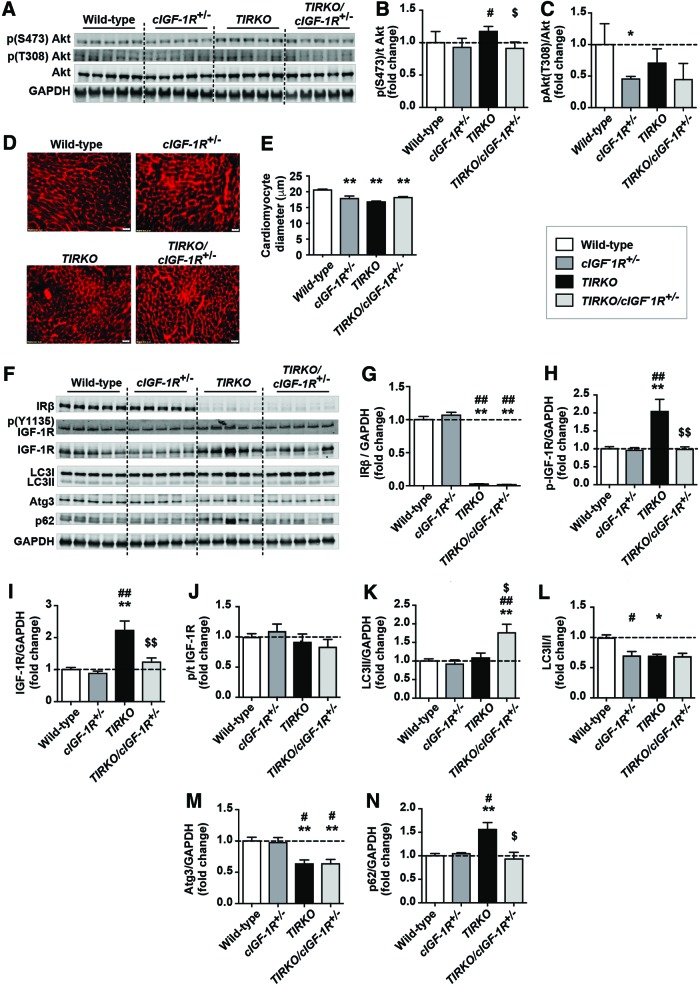

The suppression of autophagy by insulin and the increase in IGF-1R phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes lacking IRs prompted us to hypothesize that IGF-1R may be mediating the effect of hyperinsulinemia on cardiac autophagy. Thus, to directly test this hypothesis, we crossed TIRKO mice with mice lacking cardiomyocyte IGF-1R. Total deletion of both IRs and IGF-1Rs caused heart failure (24), whereas partial deletion of IGF-1R in mice lacking cardiac IRs had no such phenotype (16). Thus, we generated TIRKO mice lacking one copy of the Igf1rβ gene specifically in cardiac cells that we named TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice. We confirmed the partial deletion of IGF-1R protein and we confirmed the reduction in both total and phosphorylated IGF-1R in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− hearts by Western blot (Fig. 6F–J). We then showed that Akt phosphorylation on Ser473, which was enhanced in TIRKO hearts, was diminished to WT level in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− hearts (Fig. 6A–C). While heart weight/tibia length ratios were lower in TIRKO hearts, there was no further decrease in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice when compared with WT mice (Table 2). The reduction in heart size in TIRKO mice is consistent with diminished left ventricular mass in these mice (Table 2). There were no other significant changes in cardiac dimensions or contractile parameters between the groups (Table 2).

FIG. 6.

Partial deletion of IGF-1R in TIRKO hearts enhanced autophagy despite persistent hyperinsulinemia. (A) Representative Western blots of phospho (S473) and (T308) Akt, total Akt, and GAPDH in whole-heart homogenates from WT, cardiac-specific IGF-1R heterozygous (cIGF-1R+/−), TIRKO, and TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice. (B, C) The corresponding densitometry of phosphor (S473 or T308)/total Akt, respectively, expressed as fold change from WT controls. (D) Representative heart sections stained with WGA. (E) Quantification of cardiomyocyte diameter (μm). (F) Representative Western blots of IRβ, phospho (Y1135) IGF-1R receptor, total IGF-1R, LC3I, LC3II, Atg3, p62, and GAPDH in the same homogenates as in (A). (G–N) The corresponding densitometry of IRβ/GAPDH, p-IGF-1R/total IGF-1R, p/t IGF-1R, p-LC3II/GAPDH, LC3II/I, Atg3/GAPDH, and p62/GAPDH expressed as fold-change relative to WT mice. Data are mean ± SEM. N = 5 mice per group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus WT mice. #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 versus cIGF-1R+/− mice. $p < 0.05; $$p < 0.005 versus TIRKO mice. WGA, wheat germ agglutinin. Color images are available online.

Table 2.

Circulating Insulin Levels, Morphometric and Contractile Parameters in Wild-Type, TIRKO, cIGF-1R+/−, and TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− Mice

| WT(n = 5) | cIGF-1R+/−(n = 5) | TIRKO(n = 5) | TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/−(n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 0.78 ± 0.2 | 0.68 ± 0.3 | 11.84 ± 4**,## | 11.5 ± 1**,## |

| BW (g) | 30.3 ± 1 | 27.3 ± 2.2 | 23.2 ± 1.1** | 26.1 ± 0.3 |

| HW (g) | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.007 | 0.09 ± 0.004**,# | 0.1 ± 0.005 |

| HW/BW × 103 | 4 ± 0.03 | 4.3 ± 0.01 | 3.6 ± 0.01 | 3.8 ± 0.01 |

| HW/TL | 0.08 ± 0.006 | 0.07 ± 0.004 | 0.06 ± 0.003* | 0.06 ± 0.004 |

| WT (n = 11) | cIGF-1R+/−(n = 5) | TIRKO (n = 10) | TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/−(n = 10) | |

| LV mass, mg | 99.48 ± 4.9 | 88 ± 3 | 79.34 ± 4.3* | 85.06 ± 5.2 |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.1 | 0.82 ± 0.1 | 0.79 ± 0.08 |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 1 ± 0.06 | 1.19 ± 0.14 | 1.1 ± 0.07 |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.58 ± 0.14 | 3.6 ± 0.31 | 3.34 ± 0.19 | 3.45 ± 0.14 |

| LVIDs (mm) | 2.43 ± 0.16 | 2.88 ± 0.12 | 2.23 ± 0.18 | 2.31 ± 0.13 |

| EF (%) | 55.86 ± 3.54 | 44.4 ± 3.5 | 59.85 ± 4.95 | 59.56 ± 2.62 |

| FS (%) | 30.59 ± 2.34 | 29.5 ± 1.5 | 34.01 ± 2.33 | 33.25 ± 1.92 |

Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 versus wild-type mice; #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.005 versus cIGF-1R+/− mice.

BW, body weight; HW, heart weight; HW/BW, heart weight/body weight; HW/TL, heart weight/tibia length.

TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice also developed systemic hyperinsulinemia comparable with that observed in TIRKO mice (Table 2). Partial deletion of IGF-1R in the TIRKO background resulted in an increase in LC3II and a reduction in p62 despite sustained reduction in Atg3 (Fig. 6F–L). In contrast LC3II/I ratios were equivalently diminished in cIGF-1R+/−, TIRKO, and TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− hearts, respectively (Fig. 6L). These results suggest that systemic hyperinsulinemia may suppress autophagy in IR-deficient hearts, in part, through activation of IGF-1R signaling. However, other mechanisms may also be involved, including the sustained reduction in Atg3 in TIRKO and TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− hearts (Fig. 6M). It is also worth noting that while LC3II levels did not change in cIGF-1R+/− hearts, the ratio of LC3II/I was significantly reduced (Fig. 6L).

To investigate the downstream signaling involved in the improvement in autophagy in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− hearts, we assessed mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and forkhead Box O (FoxO) signaling. The restoration of autophagy in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice occurred in the absence of mTOR modulation as evidenced by unchanged mTOR and p70S6K phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S4A–H). Consistent with unchanged mTOR signaling, Ulk1 (Unc-51-like kinase 1) phosphorylation by mTOR on Ser757 was also not different among the groups (Supplementary Fig. S4A–H). Next, we assessed AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172, and to our surprise, we found that partial deletion of IGF-1R in WT mice reduced AMPK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. S4A–H). Consistent with diminished AMPK, Ulk1 phosphorylation at Ser555 by AMPK was also reduced in hearts lacking one copy of the IGF-1R (Supplementary Fig. S4A–H). Finally, we measured phosphorylation of FoxO1 and FoxO3a and found no significant differences between the groups (Supplementary Fig. S4A–H).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that autophagic flux is impaired and inhibition of autophagosome clearance caused cardiac dysfunction and cardiomyocyte death in IR-deficient hearts. Furthermore, we provide evidence that IR-deficient hearts can still respond to insulin, which in turn suppressed autophagy, in part, through IGF-1R signaling. This is a significant finding as prior studies in humans and animals with type 2 diabetes and systemic hyperinsulinemia showed that the heart had preserved or even exacerbated activation of IR/IGF-1R downstream signaling despite the presence of cardiac insulin resistance (5, 39). Furthermore, our group has recently shown that (ob/ob) mice develop cardiac hypertrophy, in part, via a hyperinsulinemia-mediated activation of IGF-1R signaling (39).

In the present study, we sought to determine the contribution of myocardial insulin and IGF-1 receptor signaling in autophagy suppression by systemic hyperinsulinemia. We used mice with absent IR expression in the entire heart that exhibit systemic hyperinsulinemia but no diabetes or hyperlipidemia (37). Although these mice do not recapitulate the cardiac insulin resistance often seen in humans and mouse models, they are suitable for mechanistically dissecting the relative contribution of IRs and IGF-1Rs in cardiac autophagy suppression by hyperinsulinemia.

We showed that the absence of IRs is sufficient to impair cardiac autophagic flux at the level of LC3 lipidation, as evidenced by the accumulation of LC3I both at baseline and after lysosomal inhibition by CQ. This is supported by more than 60% reduction in Atg3 protein expression in TIRKO hearts compared with WT hearts. The mechanisms underlying this decrease in Atg3 expression in TIRKO hearts may occur both at the transcriptional and the posttranslational levels as mRNA expression of this ubiquitin-like conjugating enzyme was only reduced by ∼30% (Fig. 1C). As we have not seen any difference in the protein content of Atg7 or Atg5–12 in TIRKO hearts, we propose that the lack of IRs may specifically target the degradation of Atg3 protein. This is supported by data obtained on isolated cardiomyocytes from TIRKO hearts that also exhibited ∼50% reduction in this protein (Fig. 4G). In addition to transcription, Atg3 translation can be modulated by certain microRNAs (25), and IR/IGF-1R downstream signaling was shown to modulate the expression of several microRNAs in brown adipocytes (3). In addition, the absence of IRs in mouse embryonic fibroblasts dysregulated microRNAs, independently of their ligand (2). Finally, Atg3 degradation and enzymatic activity are regulated by phosphorylation (28) and thiol oxidation (6). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the absence of IRs may alter these processes in the heart. However, additional studies are needed to examine the contribution of microRNAs and/or posttranslational modifications on Atg3 to autophagy suppression in IR-deficient hearts.

Our results showed that the autophagic flux assessed in vivo is impaired in IR-deficient hearts. This is supported by the fact that lysosomal inhibition caused more accumulation of LC3I, p62, and the mCherry LC3 signal in TIRKO hearts. It is worth noting that the mCherry-LC3 signal was higher in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts at baseline, which can be interpreted as an increase in autophagosome formation. However, fasting- or starvation-induced mCherry-LC3-positive puncta were rather diminished in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO hearts, further confirming the impairment of autophagy. To examine if the increase in mCherry-LC3 signal in TIRKO heart is due to the accumulation of LC3 aggregates, we measured LC3I and LC3II in the insoluble fraction of heart homogenates extracted in the presence of 1% Triton X-100. The presence of both LC3I and LC3II at higher levels in the insoluble fraction from mCherry-LC3 TIKRO hearts confirmed the accumulation of LC3 aggregates.

It has been debated whether basal autophagy is necessary for the maintenance of cardiac function at rest. Our results suggest that autophagy is rather needed in stress situations. Thus, mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice have normal contractile function at baseline but develop contractile dysfunction (reduced EF) when autophagosome clearance is inhibited by CQ (Table 1). Some of the mechanisms that may have caused the reduction in contractile function in mCherry-LC3 TIRKO mice include increased cardiomyocyte death and aberrant accumulation of fragmented mitochondria (Fig. 2D–G and Supplementary Fig. S2D–I). Such effects were previously reported in autophagy-deficient hearts (36). These data may also explain why diabetic hearts are susceptible to metabolic stressors such as ischemia/reperfusion, which are known to upregulate autophagy to supply ATP and eliminate damaged and fragmented mitochondria (41).

One important finding in our study is that insulin can still inhibit autophagy in the heart despite the lack of IRs. While this may be counterintuitive, this is not the first study to report such effect. Thus, a recent study showed that skeletal muscle autophagy can still be suppressed by insulin in mice rendered insulin resistant by chronic high-fat feeding (6). Furthermore, a study, using human subjects with type 2 diabetes with preserved EF, showed increased proximal insulin/IGF-1 receptor downstream signaling that correlated positively with systemic hyperinsulinemia (5). Similarly, our group and others reported a higher activation of IR downstream signaling in the hearts of mouse models of dietary and genetic obesity despite the development of cardiac insulin resistance as assessed by the rate of glucose uptake (5, 29, 39, 46). These results suggest that in the setting of IR deficiency (TIRKO mice) or insulin resistance (dietary or genetic obesity), the heart maintains its responsiveness to insulin. Our study demonstrated that in the setting of systemic hyperinsulinemia and absent IRs, IGF-1Rs are activated and this activation correlated positively with autophagy inhibition as evidenced by the accumulation of the autophagy adaptor p62. Thus, the higher the insulin levels, the higher the IGF-1R phosphorylation and p62 accumulation (Fig. 3F–H). Most importantly, IGF-1R content itself significantly correlated with p62 content in both WT and TIRKO hearts. This observation led us to examine whether IGF-1Rs respond to insulin to suppress autophagy in the heart. To test this possibility, we isolated cardiomyocytes from TIRKO mice and assessed their autophagy level when insulin was not present. Lack of IRs in the absence of insulin resulted in excessive autophagy as supported by the accumulation of LC3II and the degradation of p62, an effect reversed by the addition of insulin. These results suggested that systemic hyperinsulinemia restrains autophagy in IR-deficient hearts as mean to prevent myocyte loss. These data are consistent with previous report showing an unrestrained autophagy in mice lacking insulin and IGF-1 receptor substrates 1 and 2 (IRS1 and IRS2) in the heart (40). Although the findings by Riehle et al. (40) provided evidence that activation of IR/IGF-1R downstream signaling reduced postnatal cardiac autophagy, it was not clear what the contribution of each receptor in this suppression was.

One surprising finding in isolated IR-deficient cardiomyocytes treated with insulin is that the inhibition of autophagy by insulin occurred in the presence of IGF-1R phosphorylation but low level of Akt activation. This may suggest that autophagy inhibition by insulin in IR-deficient cardiomyocytes is Akt independent. These results are in contrast to a previous report showing that global deletion of Akt2 reversed high-fat diet-induced impairment of autophagy in the heart (46). However, whether the improvement in autophagy in Akt2-deleted mice was directly linked to the absence of this kinase or was the result of amelioration of systemic metabolism is not clear. It is also important to compare the present findings with those previously obtained in (ob/ob) mice (39). In (ob/ob) mice, the reduction in cardiac autophagy was mostly mediated by mTORC1 activation, whereas cardiac growth was, in part, due to hyperinsulinemia-mediated activation of IGF-1R/Akt signaling. In the present study, the suppression of cardiac autophagy is mostly regulated by hyperinsulinemia-induced activation of IGF-1R, whereas cardiac growth was similarly regulated by IRs/IGF-1Rs. One common finding in TIRKO and (ob/ob) hearts is the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK1/2 signaling. However, while partial reduction of IGF-1R significantly attenuated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in TIRKO mice, it did not do so in (ob/ob) hearts. These results may suggest that ERK signaling may play a key role in the suppression of cardiac autophagy by systemic hyperinsulinemia in TIRKO mice, whereas other upstream signalings may still regulate ERK signaling in (ob/ob) hearts lacking one copy of the IGF-1R. Thus, activation of MAPK/ERK through systemic hyperinsulinemia/IGF-1R activation (such as in TIRKO hearts) or through inflammation or other pathways (such in ob/ob hearts) plays an important role in the suppression of cardiac autophagy. Indeed, we previously showed that inhibition of MAPK/ERK partially restored cardiac autophagy in (ob/ob) mice (39). Future studies are needed to determine whether inhibition of MAPK/ERK can restore cardiac autophagy in TIRKO mice.

One important finding of the present study is that in the setting of IR deficiency, IGF-1Rs can compensate for the absence of IRs to suppress cardiac autophagy in response to systemic hyperinsulinemia. The improvement in cardiac autophagy in TIRKO/cIGF-1R+/− mice occurred in the presence of an equivalent hyperinsulinemia (Table 2). Downstream of IGF-1R, we did see a slight but a significant reduction in Akt phosphorylation in TIRKO mice lacking one copy of IGF-1R, which may explain the reduction in cardiomyocyte size. Surprisingly, partial deletion of IGF-1R in WT and TIRKO hearts had no effect on mTOR signaling, but significantly reduced AMPK phosphorylation as well as Ulk1 phosphorylation by this kinase (Ser555) in WT mice. These results are in contrast with studies examining the effect of IGF-1 on autophagy in cardiomyocytes, which seems to involve mTOR/AMPK signaling (44). However, it should be mentioned that our assessment of downstream signaling was performed under noninsulin-stimulated conditions.

Due to higher cardiomyocyte death in TIRKO mice when insulin was absent, we hypothesized that suppression of autophagy by IGF-1R may be necessary to prevent myocyte loss. Such a protective role for IGF-1R in the heart was previously reported (15, 31). Thus, chronic overexpression of IGF-1R in cardiomyocytes protected mice from diabetes-induced diastolic dysfunction and fibrosis (15). Although cardiac autophagy was not assessed in cardiac IGF-1R transgenic mice, there is a possibility that suppression of this process in the context of diabetes was protective. Supporting this idea is the observation that reduction of cardiac autophagy prevented cardiac damage in a type 1 diabetes mouse model (47). It is important to note that in our study, partial deletion of IGF-1R in cardiomyocytes had a minimal effect on contractile parameters under unstressed condition. These results are in sharp contrast with the results obtained on cardiac-specific IGF-1R transgenic mice, which exhibited higher systolic function. One reason for this difference could be due to the fact that the deletion of IGF-1R in our model was partial as opposed to a twofold increase in IGF-1R expression in the transgenic mice. In addition, our echocardiographic assessment of contractile function was performed at rest, suggesting that autophagy may be needed in situations of energetic stress.

The present study has some limitations such as using mice with deficient IRs in the heart, which does not recapitulate the insulin-resistant state often seen in humans and in mice with type 2 diabetes. However, we used these mice to dissect the contribution of IRs and IGF-1Rs in hyperinsulinemia-mediated suppression of cardiac autophagy. Another limitation of this study is that we did not investigate the relative contribution of Akt and ERK signaling in the suppression of cardiac autophagy through IGF-1R. Finally, we only assessed cardiac function at baseline in WT and TIRKO mice lacking one copy of cardiomyocyte IGF-1R. Thus, future studies involving ischemia/reperfusion or pressure overload stress may reveal the functional significance of enhancing autophagy in IR-deficient/resistant hearts.

Materials and Methods

Animals, diet, and treatment

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85 23, revised 1996) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah. TIRKO (or Ttr-Insr−/−) mice were engineered to rescue the lethality of whole-body IR knockout mice by overexpressing a human IR cDNA from the transthyretin promoter in the liver, brain, and beta-cells, respectively (37). Male TIRKO mice (on a C57B/6J background) and their respective WT control mice were used between 10 and 14 weeks of age. TIRKO and WT mice expressing the mCherry-LC3 transgene (referred to as mCherry-LC3 WT and mCherry-LC3 TIRKO) in cardiac cells were generated by crossing WT and TIRKO mice with mice carrying the α-MHC-mCherry-LC3 (17) on a mixed background. WT and TIRKO mice lacking one allele of IGF-1R in cardiomyocytes were generated by crossing WT and TIRKO mice with mice lacking IGF-1R specifically in cardiomyocytes generated on a mixed background (20). For CQ treatment, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of saline or 10 μg/kg BW CQ for 4 h before sacrifice as previously described (17).

Echocardiography measurements

Cardiac function was monitored at rest using transthoracic echocardiography as previously described (30). Measurements were performed in lightly anesthetized (isoflurane, 2%) mice with a Vevo 2100 high-resolution echocardiography machine equipped with a 22–55 MHz transducer (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON). Measurements were performed on three independently acquired images per animal, by investigators who were blinded to the experimental groups. All acquisitions were analyzed using the VevoStrain software (VisualSonics).

Serum insulin and IGF-1 levels

Random fed mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture. Insulin was determined from 10 to 30 μL of plasma (12,000 g; 15 min; 4°C) using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit; Crystal Chem, Inc). Serum IGF-1 levels were determined using commercial radioimmunoassay (Sigma, EMIGF1).

Cardiomyocyte isolation and insulin treatment

Ventricular myocytes were isolated from adult mice by collagenase/protease digestion as previously described (23). We stored the cells in a 1 mM Ca2+-4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid-buffered saline solution at room temperature until use. Cells were gently spun down (9000 g for 5 min), resuspended in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; high glucose, pyruvate; Invitrogen), and treated with 100 nM of insulin (Sigma) for 120 min.

H9c2 culture

Undifferentiated H9c2 cardiac myoblasts were purchased from ATCC and kept in complete DMEM (ATCC, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. To mimic the hyperinsulinemic milieu, cells were incubated with media containing 100 nM insulin (Sigma) for 120 min. After treatment, H9C2 cells were lysed in cold RIPA buffer (Invitrogen) added with Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Invitrogen). After centrifugation at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatants were collected, and the total protein content was measured spectrophotometrically using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Invitrogen). Western blot analysis was performed according to standard procedures.

Histology

Following euthanasia, mouse hearts were excised, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma) for 48 h, and embedded in paraffin, and 5 μm sections were cut. For cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area measurement, sections were counterstained with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; Alexa Fluor™ 594 Conjugate; Invitrogen) and mounted with ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen).

Cell death assay

Sections were deparaffinized, permeabilized by treatment with Triton X-100 (0.01%), and incubated with TdT enzyme in reaction buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red; Sigma).

Morphometry

For quantification purposes, at least 5 images per section were taken, and 10 fields per image were analyzed using CellSens dimension viewing software (Version 1.1.3; Olympus). The area was assessed on fibers with circular shapes in a blinded manner by quantitative image analysis using CellSens Dimension software. The images were acquired with an XM10 Olympus fluorescence camera.

Mcherry-LC3-positive signal quantification

Numbers of mCherry-LC3-positive signal per DAPI were quantified in snap-frozen tissue-TEK 10 μm heart sections counterstained with DAPI and WGA (Alexa Fluor 488; Invitrogen) using the CellSens Dimension viewing software (Version 1.1.3; Olympus). Images were acquired with an XM10 Olympus fluorescence camera and at least five random 40 × fields were analyzed per heart.

LDH release assay

For quantitative assessment of cardiomyocyte necrosis, LDH release in culture medium was measured using the LDH cytotoxicity assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche).

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy samples were prepared and processed at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the University of Utah. Briefly, small pieces of left ventricular tissue from the left ventricle were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate with 2.4% sucrose and 8 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4) for at least 1 day. Samples were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, stained in bloc with aqueous uranyl acetate, and dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes (50% up to 100%). Fixed samples were then infiltrated and embedded in Spur's plastic and processed for electron microscopy. Mitochondrial morphology was assessed, and mitochondrial number was determined in 16 pictures per group (n = 4 hearts and 4 pictures per heart).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from frozen heart muscle as previously described (39). To detect LC3I and LC3II in the insoluble fraction, hearts were extracted in the presence of 1% Triton X-100. A list of antibodies and primers used is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

mRNA was quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction using an ABI Prism 7900HT instrument in 384-well plate format as described previously (11). Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means. Unpaired Student's t-test was used to analyze differences relative to WT controls. One-way or two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze differences by genotype and by treatment, followed by Bonferroni protected least significant difference test. Statistical calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). For all analyses, a p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants 1-R01-DK-098646-01A1 and R01-DK-099110 and the American Heart Association (AHA) grant 16GRNT30990018 to S.B. K.M.P. was supported by AHA postdoctoral fellowship 15POST25360014. R.G. was supported by grant 5R25MD006781-05 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). R.A.G. was supported by P01 HL112730 and R01 HL132075. C.H.S. was supported by grant R01HL089592-02 from NHLBI. We thank Dr. E. Dale Abel (University of Iowa) for providing TIRKO and cardiac IGF-1R−/− mice. We acknowledge Mrs. Diana Lim for her assistance in the preparation of the figures. We thank Mrs. Nancy Chandler for her assistance with electron microscopy and Mr. Alan Achenbach for his assistance in English proofing the article.

Abbreviations Used

- α-MHC

α-myosin heavy chain

- Akt

protein kinase B

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- Atg

autophagy-related protein

- BW

body weight

- CQ

chloroquine

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EF

ejection fraction

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- FoxO

forkhead Box O

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGF-1R

IGF-1 receptor

- IR

insulin receptor

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- Sqstm1 (p62)

sequestosome 1

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TIRKO

Ttr-Insr−/−

- Ulk1

Unc-51-like kinase 1

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

- WT

wild-type

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 387: 1513–1530, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boucher J, Charalambous M, Zarse K, Mori MA, Kleinridders A, Ristow M, Ferguson-Smith AC, Kahn CR. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors are required for normal expression of imprinted genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 14512–14517, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boudina S, Sena S, Theobald H, Sheng X, Wright JJ, Hu XX, Aziz S, Johnson JI, Bugger H, Zaha VG, Abel ED. Mitochondrial energetics in the heart in obesity-related diabetes: direct evidence for increased uncoupled respiration and activation of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 56: 2457–2466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colombo L, Baldari G, Logi G, Lusini A. [The use of levulose in resuscitation]. Acta Anaesthesiol 20: Suppl 2:79–90, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook SA, Varela-Carver A, Mongillo M, Kleinert C, Khan MT, Leccisotti L, Strickland N, Matsui T, Das S, Rosenzweig A, Punjabi P, Camici PG. Abnormal myocardial insulin signalling in type 2 diabetes and left-ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J 31: 100–111, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frudd K, Burgoyne T, Burgoyne JR. Oxidation of Atg3 and Atg7 mediates inhibition of autophagy. Nat Commun 9: 95, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fujita N, Itoh T, Omori H, Fukuda M, Noda T, Yoshimori T. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2092–2100, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Godar RJ, Ma X, Liu H, Murphy JT, Weinheimer CJ, Kovacs A, Crosby SD, Saftig P, Diwan A. Repetitive stimulation of autophagy-lysosome machinery by intermittent fasting preconditions the myocardium to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Autophagy 11: 1537–1560, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith SC, Jr., Sowers JR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 100: 1134–1146, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gubbiotti MA, Seifert E, Rodeck U, Hoek JB, Iozzo RV. Metabolic reprogramming of murine cardiomyocytes during autophagy requires the extracellular nutrient sensor decorin. J Biol Chem 293: 16940–16950, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han YH, Buffolo M, Pires KM, Pei S, Scherer PE, Boudina S. Adipocyte-specific deletion of manganese superoxide dismutase protects from diet-induced obesity through increased mitochondrial uncoupling and biogenesis. Diabetes 65: 2639–2651, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet 43: 67–93, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. He C, Zhu H, Li H, Zou MH, Xie Z. Dissociation of Bcl-2-Beclin1 complex by activated AMPK enhances cardiac autophagy and protects against cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetes. Diabetes 62: 1270–1281, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hsu HC, Chen CY, Lee BC, Chen MF. High-fat diet induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis via the inhibition of autophagy. Eur J Nutr 55: 2245–2254, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huynh K, McMullen JR, Julius TL, Tan JW, Love JE, Cemerlang N, Kiriazis H, Du XJ, Ritchie RH. Cardiac-specific IGF-1 receptor transgenic expression protects against cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in a mouse model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 59: 1512–1520, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ikeda H, Shiojima I, Ozasa Y, Yoshida M, Holzenberger M, Kahn CR, Walsh K, Igarashi T, Abel ED, Komuro I. Interaction of myocardial insulin receptor and IGF receptor signaling in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 47: 664–675, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iwai-Kanai E, Yuan H, Huang C, Sayen MR, Perry-Garza CN, Kim L, Gottlieb RA. A method to measure cardiac autophagic flux in vivo. Autophagy 4: 322–329, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jaishy B, Zhang Q, Chung HS, Riehle C, Soto J, Jenkins S, Abel P, Cowart LA, Van Eyk JE, Abel ED. Lipid-induced NOX2 activation inhibits autophagic flux by impairing lysosomal enzyme activity. J Lipid Res 56: 546–561, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kanamori H, Takemura G, Goto K, Tsujimoto A, Mikami A, Ogino A, Watanabe T, Morishita K, Okada H, Kawasaki M, Seishima M, Minatoguchi S. Autophagic adaptations in diabetic cardiomyopathy differ between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Autophagy 11: 1146–1160, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J, Wende AR, Sena S, Theobald HA, Soto J, Sloan C, Wayment BE, Litwin SE, Holzenberger M, LeRoith D, Abel ED. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling is required for exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Endocrinol 22: 2531–2543, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi S, Xu X, Chen K, Liang Q. Suppression of autophagy is protective in high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Autophagy 8: 577–592, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lancel S, Montaigne D, Marechal X, Marciniak C, Hassoun SM, Decoster B, Ballot C, Blazejewski C, Corseaux D, Lescure B, Motterlini R, Neviere R. Carbon monoxide improves cardiac function and mitochondrial population quality in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. PLoS One 7: e41836, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Larbig R, Torres N, Bridge JH, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. Activation of reverse Na+-Ca2+ exchange by the Na+ current augments the cardiac Ca2+ transient: evidence from NCX knockout mice. J Physiol 588: 3267–3276, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laustsen PG, Russell SJ, Cui L, Entingh-Pearsall A, Holzenberger M, Liao R, Kahn CR. Essential role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling in cardiac development and function. Mol Cell Biol 27: 1649–1664, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li W, Yang Y, Hou X, Zhuang H, Wu Z, Li Z, Guo R, Chen H, Lin C, Zhong W, Chen Y, Wu K, Zhang L, Feng D. MicroRNA-495 regulates starvation-induced autophagy by targeting ATG3. FEBS Lett 590: 726–738, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li ZL, Woollard JR, Ebrahimi B, Crane JA, Jordan KL, Lerman A, Wang SM, Lerman LO. Transition from obesity to metabolic syndrome is associated with altered myocardial autophagy and apoptosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1132–1141, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lum JJ, Bauer DE, Kong M, Harris MH, Li C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell 120: 237–248, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma K, Fu W, Tang M, Zhang C, Hou T, Li R, Lu X, Wang Y, Zhou J, Li X, Zhang L, Wang L, Zhao Y, Zhu WG. PTK2-mediated degradation of ATG3 impedes cancer cells susceptible to DNA damage treatment. Autophagy 13: 579–591, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mazumder PK, O'Neill BT, Roberts MW, Buchanan J, Yun UJ, Cooksey RC, Boudina S, Abel ED. Impaired cardiac efficiency and increased fatty acid oxidation in insulin-resistant ob/ob mouse hearts. Diabetes 53: 2366–2374, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McKellar SH, Javan H, Bowen ME, Liu X, Schaaf CL, Briggs CM, Zou H, Gomez AD, Abdullah OM, Hsu EW, Selzman CH. Animal model of reversible, right ventricular failure. J Surg Res 194: 327–333, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McMullen JR, Shioi T, Huang WY, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Bisping E, Schinke M, Kong S, Sherwood MC, Brown J, Riggi L, Kang PM, Izumo S. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) pathway. J Biol Chem 279: 4782–4793, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mellor KM, Bell JR, Young MJ, Ritchie RH, Delbridge LM. Myocardial autophagy activation and suppressed survival signaling is associated with insulin resistance in fructose-fed mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 50: 1035–1043, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 314: 1021–1029, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Munasinghe PE, Riu F, Dixit P, Edamatsu M, Saxena P, Hamer NS, Galvin IF, Bunton RW, Lequeux S, Jones G, Lamberts RR, Emanueli C, Madeddu P, Katare R. Type-2 diabetes increases autophagy in the human heart through promotion of Beclin-1 mediated pathway. Int J Cardiol 202: 13–20, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naito T, Kuma A, Mizushima N. Differential contribution of insulin and amino acids to the mTORC1-autophagy pathway in the liver and muscle. J Biol Chem 288: 21074–21081, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, Nishida K, Hori M, Mizushima N, Otsu K. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med 13: 619–624, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okamoto H, Nakae J, Kitamura T, Park BC, Dragatsis I, Accili D. Transgenic rescue of insulin receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 114: 214–223, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paula-Gomes S, Gonçalves DAP, Baviera AM, Zanon NM, Navegantes LCC, Kettelhut IC. Insulin suppresses atrophy- and autophagy-related genes in heart tissue and cardiomyocytes through AKT/FOXO signaling. Horm Metab Res 45: 849–855, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pires KM, Buffolo M, Schaaf C, David Symons J, Cox J, Abel ED, Selzman CH, Boudina S. Activation of IGF-1 receptors and Akt signaling by systemic hyperinsulinemia contributes to cardiac hypertrophy but does not regulate cardiac autophagy in obese diabetic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 113: 39–50, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Riehle C, Wende AR, Sena S, Pires KM, Pereira RO, Zhu Y, Bugger H, Frank D, Bevins J, Chen D, Perry CN, Dong XC, Valdez S, Rech M, Sheng X, Weimer BC, Gottlieb RA, White MF, Abel ED. Insulin receptor substrate signaling suppresses neonatal autophagy in the heart. J Clin Invest 123: 5319–5333, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sciarretta S, Zhai P, Shao D, Maejima Y, Robbins J, Volpe M, Condorelli G, Sadoshima J. Rheb is a critical regulator of autophagy during myocardial ischemia: pathophysiological implications in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Circulation 125: 1134–1146, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shcherbakov AS. [Special prosthoelontic methods for patients with microstomia]. Stomatologiia (Mosk) 48: 78–80, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 16: 434–444, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Troncoso R, Vicencio JM, Parra V, Nemchenko A, Kawashima Y, Del Campo A, Toro B, Battiprolu PK, Aranguiz P, Chiong M, Yakar S, Gillette TG, Hill JA, Abel ED, Leroith D, Lavandero S. Energy-preserving effects of IGF-1 antagonize starvation-induced cardiac autophagy. Cardiovasc Res 93: 320–329, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xie Z, Lau K, Eby B, Lozano P, He C, Pennington B, Li H, Rathi S, Dong Y, Tian R, Kem D, Zou MH. Improvement of cardiac functions by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced cardiac autophagy in diabetic OVE26 mice. Diabetes 60: 1770–1778, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu X, Hua Y, Nair S, Zhang Y, Ren J. Akt2 knockout preserves cardiac function in high-fat diet-induced obesity by rescuing cardiac autophagosome maturation. J Mol Cell Biol 5: 61–63, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu X, Kobayashi S, Chen K, Timm D, Volden P, Huang Y, Gulick J, Yue Z, Robbins J, Epstein PN, Liang Q. Diminished autophagy limits cardiac injury in mouse models of type 1 diabetes. J Biol Chem 288: 18077–18092, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu X, Ren J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) knockout preserves cardiac homeostasis through alleviating Akt-mediated myocardial autophagy suppression in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 39: 387–396, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.