Abstract

Objective

To generate estimates of the global prevalence and incidence of urogenital infection with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis in women and men, aged 15–49 years, in 2016.

Methods

For chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis, we systematically searched for studies conducted between 2009 and 2016 reporting prevalence. We also consulted regional experts. To generate estimates, we used Bayesian meta-analysis. For syphilis, we aggregated the national estimates generated by using Spectrum-STI.

Findings

For chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or trichomoniasis, 130 studies were eligible. For syphilis, the Spectrum-STI database contained 978 data points for the same period. The 2016 global prevalence estimates in women were: chlamydia 3.8% (95% uncertainty interval, UI: 3.3–4.5); gonorrhoea 0.9% (95% UI: 0.7–1.1); trichomoniasis 5.3% (95% UI:4.0–7.2); and syphilis 0.5% (95% UI: 0.4–0.6). In men prevalence estimates were: chlamydia 2.7% (95% UI: 1.9–3.7); gonorrhoea 0.7% (95% UI: 0.5–1.1); trichomoniasis 0.6% (95% UI: 0.4–0.9); and syphilis 0.5% (95% UI: 0.4–0.6). Total estimated incident cases were 376.4 million: 127.2 million (95% UI: 95.1–165.9 million) chlamydia cases; 86.9 million (95% UI: 58.6–123.4 million) gonorrhoea cases; 156.0 million (95% UI: 103.4–231.2 million) trichomoniasis cases; and 6.3 million (95% UI: 5.5–7.1 million) syphilis cases.

Conclusion

Global estimates of prevalence and incidence of these four curable sexually transmitted infections remain high. The study highlights the need to expand data collection efforts at country level and provides an initial baseline for monitoring progress of the World Health Organization global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021.

Résumé

Objectif

Produire des estimations de la prévalence et de l'incidence mondiales des infections urogénitales dues à la chlamydiose, à la gonorrhée, à la trichomonase et à la syphilis chez les femmes et les hommes de 15 à 49 ans, en 2016.

Méthodes

Pour la chlamydiose, la gonorrhée et la trichomonase, nous avons systématiquement recherché les études menées entre 2009 et 2016 qui s’intéressaient à la prévalence. Nous avons également consulté des experts régionaux. Pour produire des estimations, nous avons eu recours à une méta-analyse bayésienne. Pour la syphilis, nous avons regroupé les estimations nationales obtenues à l'aide de Spectrum-STI.

Résultats

Pour la chlamydiose, la gonorrhée et/ou la trichomonase, 130 études étaient éligibles. Pour la syphilis, la base de données de Spectrum-STI contenait 978 points de données pour la période considérée. Les estimations de la prévalence mondiale en 2016 chez les femmes étaient les suivantes: chlamydiose 3,8% (intervalle d'incertitude de 95%, II: 3,3–4,5); gonorrhée 0,9% (II 95%: 0,7–1,1); trichomonase 5,3% (II 95%: 4,0–7,2); et syphilis 0,5% (II 95%: 0,4–0,6). Chez les hommes, les estimations de la prévalence étaient les suivantes: chlamydiose 2,7% (II 95%: 1,9-3,7); gonorrhée 0,7% (II 95%: 0,5-1,1); trichomonase 0,6% (II 95%: 0,4-0,9); et syphilis 0,5% (II 95%: 0,4–0,6). L'incidence totale estimée était de 376,4 millions de cas: 127,2 millions (II 95%: 95,1–165,9 millions) de cas de chlamydiose; 86,9 millions (II 95%: 58,6-123,4 millions) de cas de gonorrhée; 156,0 millions (II 95%: 103,4-231,2 millions) de cas de trichomonase; et 6,3 millions (II 95%: 5,5–7,1 millions) de cas de syphilis.

Conclusion

Les estimations mondiales de la prévalence et de l'incidence de ces quatre infections sexuellement transmissibles guérissables restent élevées. Cette étude souligne la nécessité d'amplifier les efforts de collecte de données au niveau des pays et offre un point de référence pour suivre la progression de la Stratégie mondiale du secteur de la santé contre les IST 2016–2021 de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé.

Resumen

Objetivo

Generar estimaciones de la prevalencia y la incidencia mundiales de la infección urogenital por clamidia, gonorrea, tricomoniasis y sífilis en mujeres y hombres de 15 a 49 años de edad en 2016.

Métodos

Para la clamidia, la gonorrea y la tricomoniasis, se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas de estudios realizados entre 2009 y 2016 que registrasen la prevalencia. También se consultó a expertos regionales. Para generar estimaciones, se utilizó el metanálisis bayesiano. Para la sífilis, se añadieron las estimaciones nacionales generadas por el uso de Spectrum-STI.

Resultados

Para la clamidia, la gonorrea y/o la tricomoniasis, hubo 130 estudios que cumplían los criterios. Para la sífilis, la base de datos Spectrum-STI contenía 978 puntos de datos para el mismo periodo. Las estimaciones de prevalencia mundial en mujeres en 2016 fueron: clamidia 3,8 % (intervalo de incertidumbre, II, del 95 %: 3,3-4,5); gonorrea 0,9 % (II del 95 %: 0,7-1,1); tricomoniasis 5,3 % (II del 95 %: 4,0-7,2); y sífilis 0,5 % (II del 95 %: 0,4-0,6). Las estimaciones de prevalencia en hombres fueron: clamidia 2,7 % (intervalo de incertidumbre, II, del 95 %: 1,9-3,7); gonorrea 0,7 % (II del 95 %: 0,5-1,1); tricomoniasis 0,6 % (II del 95 %: 0,4-0,9); y sífilis 0,5 % (II del 95 %: 0,4-0,6). El total estimado de casos incidentes fue de 376,4 millones: 127,2 millones (II del 95 %: 95,1-165,9 millones) de casos de clamidia; 86,9 millones (II del 95 %: 58,6-123,4 millones) de casos de gonorrea; 156,0 millones (II del 95 %: 103,4-231,2 millones) de casos de tricomoniasis; y 6,3 millones (II del 95 %: 5,5-7,1 millones) de casos de sífilis.

Conclusión

Las estimaciones mundiales de la prevalencia y la incidencia de estas cuatro enfermedades de transmisión sexual curables siguen siendo elevadas. El estudio destaca la necesidad de ampliar los esfuerzos de recopilación de datos a nivel nacional y proporciona una base inicial para el seguimiento de los progresos de la Estrategia Mundial del Sector de la Salud de la Organización Mundial de la Salud sobre las ETS entre 2016 y 2021.

ملخص

الغرض

وضع تقديرات للانتشار والإصابة العالمية لعدوى الجهاز البولي التناسلي، وأمراض الكلاميديا، والسيلان، وداء المشعرات، والزهري لدى النساء والرجال، الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 15 و49 سنة، في عام 2016.

الطريقة

بالنسبة للكلاميديا، والسيلان، وداء المشعرات، فقد قمنا بالبحث بشكل منهجي عن الدراسات التي تمت خلال الفترة من 2009 إلى 2016 والتي توضح مدى الانتشار. كما قمنا باستشارة خبراء إقليميين. ولوضع التقديرات، قمنا باستخدام التحليل التلوي Bayesian. بالنسبة لمرض الزهري، قمنا بتجميع التقديرات الوطنية الناتجة عن استخدام Spectrum-STI.

النتائج

بالنسبة لأمراض الكلاميديا، والسيلان، وداء المشعرات، كانت هناك 130 دراسة مؤهلة. وبالنسبة لمرض الزهري، احتوت قادة بيانات Spectrum-STI على 978 نقطة بيانات لنفس الفترة. كانت تقديرات الانتشار العالمي في عام 2016 في النساء: الكلاميديا 3.8% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 3.3 إلى 4.5)، والسيلان 0.9% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 0.7 إلى 1.1)، وداء المشعرات 5.3% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 4.0 إلى 7.2)؛ والزهري 0.5% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 0.4 إلى 0.6). كانت تقديرات الانتشار في عام 2016 في الرجال: الكلاميديا 2.7% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 1.9 إلى 3.7)، والسيلان 0.7% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 0.5 إلى 1.1)، وداء المشعرات 0.6% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 0.4 إلى 0.9)، والزهري 0.5% (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 0.4–0.6). بلغ مجموع حالات الإصابة التقديري 376.4 مليون حالة: 127.2 مليون (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 95.1 إلى 165.9 مليون) حالات الكلاميديا؛ 86.9 مليون (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 58.6 إلى 123.4 مليون) حالات السيلان؛ 156.0 مليون (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 103.4 إلى 231.2 مليون) حالات داء المشعرات؛ 6.3 مليون (فاصل عدم الثقة 95%: 5.5 إلى 7.1 مليون) حالات الزهري.

الاستنتاج

لا تزال التقديرات العالمية عالية لانتشار والإصابة بهذه الأمراض الأربعة المنقولة جنسياً والعلاج منها. تسلط الدراسة الضوء على الحاجة إلى توسيع جهود جمع البيانات على مستوى الدول، وتوفر خط أساس أولي لمراقبة التقدم المحرز في إستراتيجية قطاع الصحة العالمية التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية بشأن الأمراض المنقولة جنسياً خلال الفترة من 2016 إلى 2021.

摘要

目的

旨在估计 2016 年 15-49 岁男女泌尿生殖系统感染衣原体病、淋病、滴虫病和梅毒的全球患病率和发病率。

方法

对于衣原体病、淋病和滴虫病,我们系统搜索了 2009 年至 2016 年间的患病率报告研究。我们还咨询了区域专家。为了生成估计值,我们使用了贝叶斯荟萃分析。对于梅毒,我们汇总分析了使用 Spectrum-STI 生成的全国估计值。

结果

对于衣原体病、淋病和/或滴虫病,符合要求的有 130 项研究。对于梅毒, Spectrum-STI 数据库包含了同一时期的 978 个数据点。2016 年,全球女性患病率估计值为:衣原体病 3.8%(95% 不确定区间,UI:3.3-4.5);淋病 0.9%(95% UI:0.7–1.1);滴虫病 5.3%(95% UI:4.0–7.2)和梅毒 0.5%(95% UI:0.4-0.6)。全球男性患病率估计值为:衣原体病 2.7%(95% UI:1.9-3.7);淋病 0.7%(95% UI:0.5-1.1);滴虫病 0.6%(95% UI:0.4-0.9);梅毒 0.5%(95% UI:0.4-0.6)。预计病例总数为 3.764 亿:1.272 亿(95% UI:9510-16590 万)衣原体病病例;8690 万(95% UI:5860-12340 万)淋病病例;15600 万(95% UI:10340-23120 万)滴虫病病例;630 万(95% UI:550-710 万)梅毒病例。

结论

对这四种可治愈的性传播疾病的患病率和发病率的全球估计值仍然很高。该研究强调了扩大国家级数据收集工作的必要性,并为监测 2016 至 2021 年世卫组织全球卫生部门性传播疾病战略的进展提供了初始基线。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить распространенность в мировом масштабе и частоту урогенитальных инфекций, вызываемых хламидией, а также гонореи, трихомониаза и сифилиса у мужчин и женщин в возрасте от 15 до 49 лет по состоянию на 2016 год.

Методы

Для хламидиоза, гонореи и трихомониаза авторы провели систематический поиск исследований, выполненных в период с 2009 по 2016 год, в которых приводились данные по распространенности заболеваний. Авторы также консультировались с международными специалистами. Для оценки использовался байесовский метаанализ. Для исследования сифилиса нами были объединены национальные оценки, созданные с использованием методики Spectrum-STI.

Результаты

Было обнаружено 130 исследований на тему хламидийной инфекции, гонореи и (или) трихомониаза. Что касается сифилиса, база данных Spectrum-STI за тот же период содержала 978 источников данных. По состоянию на 2016 год распространенность изучаемых заболеваний в мире среди женщин составляла: хламидиоз 3,8% (95%-й интервал неопределенности, ИН: 3,3–4,5), гонорея 0,9% (95%-й ИН: 0,7–1,1), трихомониаз 5,3% (95%-й ИН: 4,0–7,2) и сифилис 0,5% (95%-й ИН: 0,4–0,6). У мужчин распространенность хламидиоза составила 2,7% (95%-й ИН: 1,9–3,7), гонореи 0,7% (95%-й ИН: 0,5–1,1), трихомониаза 0,6% (95%-й ИН: 0,4–0,9) и сифилиса 0,5% (95%-й ИН: 0,4–0,6). Общее приблизительное количество случаев заболевания составило 376,4 млн человек: 127,2 млн (95 %-й ИН: 95,1–165,9 млн) случаев хламидийной инфекции, 86,9 млн (95%-й ИН: 58,6–123,4 млн) случаев гонореи, 156,0 млн (95%-й ИН: 103,4–231,2 млн) случаев трихомониаза и 6,3 млн (95%-й ИН: 5,5–7,1 млн) случаев сифилиса.

Вывод

Оценки мировой распространенности и частоты этих четырех излечимых инфекций, передаваемых половым путем (ИППП), остаются высокими. Исследование показывает необходимость предпринимать дальнейшие усилия по сбору данных на уровне каждой страны и может служить источником базовых значений для мониторинга прогресса в исполнении глобальных стратегий ВОЗ в секторе здравоохранения относительно ИППП на период 2016–2021 гг.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections are among the most common communicable conditions and affect the health and lives of people worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) periodically generates estimates to gauge the global burden of four of the most common curable sexually transmitted infections: chlamydia (etiological agent: Chlamydia trachomatis), gonorrhoea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae), trichomoniasis (Trichomonas vaginalis) and syphilis (Treponema pallidum).1–6 The estimates provide evidence for programme improvement, monitoring and evaluation.

These sexually transmitted infections cause acute urogenital conditions such as cervicitis, urethritis, vaginitis and genital ulceration, and some of the etiological agents also infect the rectum and pharynx. Chlamydia and gonorrhoea can cause serious short- and long-term complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, chronic pelvic pain and arthritis, and they can be transmitted during pregnancy or delivery. Syphilis can cause neurological, cardiovascular and dermatological disease in adults, and stillbirth, neonatal death, premature delivery or severe disability in infants. All four infections are implicated in increasing the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition and transmission.7 Moreover, people with sexually transmitted infections often experience stigma, stereotyping, vulnerability, shame and gender-based violence.8

In May 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted the Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections, 2016–2021.9 This strategy includes rapid scale-up of evidence-based interventions and services to end sexually transmitted infections as public health concerns by 2030. The strategy sets targets for reductions in gonorrhoea and syphilis incidence in adults and recommends the establishment of global baseline incidences of sexually transmitted infections by 2018. The primary objectives of this study were to estimate the 2016 global and regional prevalence and incidence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis in adult women and men.

Methods

Prevalence estimation

Chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis

We generated estimates for these three infections through systematic reviews using the same methods as for the 2012 estimates.6

We searched for articles published between 1 January 2009 and 29 July 2018 in PubMed® without language restrictions. We used PubMed Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms for individual country names combined with: “chlamydia”[MeSH Terms] OR “chlamydia”[All Fields], “gonorrhoea”[All Fields] OR “gonorrhea”[MeSH Terms] OR “gonorrhea”[All Fields], “trichomonas infections”[MeSH Terms] OR (“trichomonas”[All Fields] AND “infections”[All Fields]) OR “trichomonas infections”[All Fields] OR “trichomoniasis”[All Fields]). We also asked WHO regional sexually transmitted infection advisors and other leading experts in the field for additional published and unpublished data.

To be eligible, studies had to collect most specimens between 2009 and 2016 or be published in 2010 or later if specimen collection dates were not available. Other study inclusion criteria were: sample size of at least 100 individuals; general population (e.g. pregnant women, women at delivery, women attending family planning clinics, men and women selected for participation in demographic and health surveys); and use of an internationally recognized diagnostic test with demonstrated precision using urine, urethral, cervical or vaginal specimens.

To reduce bias in the estimation of general population prevalence, we excluded studies conducted among the following groups: patients seeking care for sexually transmitted infection or urogenital symptoms, women presenting at gynaecology or sexual health clinics with sexually transmitted infection related issues, studies restricted to women with abnormal Papanicolaou test results, remote or indigenous populations, recent immigrant or migrant populations, men who have sex with men and commercial sex workers.

Two investigators independently reviewed all identified studies to verify eligibility. When more than one publication reported on the same population, we retained the publication with the most detailed information. For each included study, we calculated prevalence as the number of individuals with a positive test result divided by the total number tested. We then standardized these values by applying adjustment factors for the accuracy of the laboratory diagnostic test, study location (rural versus urban) and the age of the study population. If the adjustments resulted in a negative value, we replaced the value with 0.1% when doing the meta-analysis. The methods and adjustment factors were identical to those used to generate the 2012 estimates.6

We obtained estimates for 10 geographical areas (referred to as estimation regions).6 Estimates for high-income North America (Canada and United States of America), were based on the latest published United States estimates that used data from multiple sources.10,11 For the other nine estimation regions, we calculated a summary prevalence estimate by meta-analysis if there were three or more data points.12 There were sufficient data to generate an estimate for chlamydia in women in all regions, but not for gonorrhoea or trichomoniasis. For regions with insufficient data for gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis, we assumed that prevalence was a multiple of the prevalence of chlamydia. The infection specific multiples were based on those studies that met the 2016 inclusion criteria (available from the data repository).13 For men, when there were insufficient data for meta-analysis, the prevalence of an infection was assumed to be proportional to the prevalence in women. The male-to-female ratios were infection-specific and were set at the same values as in 2012 estimates.6

To reflect the contribution of populations at higher risk of infection (e.g. men who have sex with men and commercial sex workers), who are likely to be under-represented in general population samples, we increased prevalence estimates by 10%, as in the 2012 estimates,6 for each estimation region, apart from high-income North America.

We performed the meta-analyses using a Bayesian approach with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm implemented with the software BRrugs in R package (R foundation, Vienna, Austria).14 For each infection, the software generated 10 000 samples from the posterior distribution for the expected mean prevalence in each estimation region based on the β-binomial model, and used these to calculate the 2.5 and 97.5 uncertainty percentiles.15 We calculated global and regional prevalence estimates for each infection by weighting each of the 10 000 samples from estimation regions according to population size, using United Nations population data for women and men aged 15–49 years.16 We present results by WHO region, 2016 World Bank income classification17 and 2017 sustainable development goal (SDG) region.18 All analyses were carried out using R statistical software (R foundation).

Syphilis

We based syphilis estimates on the WHO’s published 2016 maternal prevalence estimates.19 These estimates were generated by using Spectrum-STI, a statistical trend-fitting model in the publicly available Spectrum suite of health policy planning tools20 and country specific data from the global Spectrum-STI syphilis database (available from the corresponding author). As in the 2012 estimation,6 we assumed that the prevalence of syphilis in all women 15–49 years of age in each country was the same as in pregnant women. We then increased the estimate by 10% to reflect the contribution of populations at higher risk. The men to women prevalence ratio of syphilis was set at 1.0 and assumed to have a uniform distribution ± 33% around this value, in agreement with data from a recent global meta-analysis of syphilis.21

We generated regional and global estimates by weighting the contribution of each country by the number of women and men aged 15–49 years. Regional and global 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) were generated using the delta method;22 uncertainties were assumed to be independent across countries.

Incidence estimation

We calculated incidence estimates for each infection by dividing prevalence by the average duration of infection for all estimation regions except high-income North America where published estimates were used.10,11 Estimates of the average duration of infection were those used in the 2012 estimation6 and assumed to have a uniform distribution of ± 33.3% around the average duration. We calculated uncertainty in incidence for a given region, sex and infection at the national level using the delta method;22 uncertainty in the prevalence estimate was multiplied by uncertainty in the estimated duration of infection. Regional and global uncertainty intervals were generated assuming uncertainties were independent across countries.

Results

Data availability

Chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis

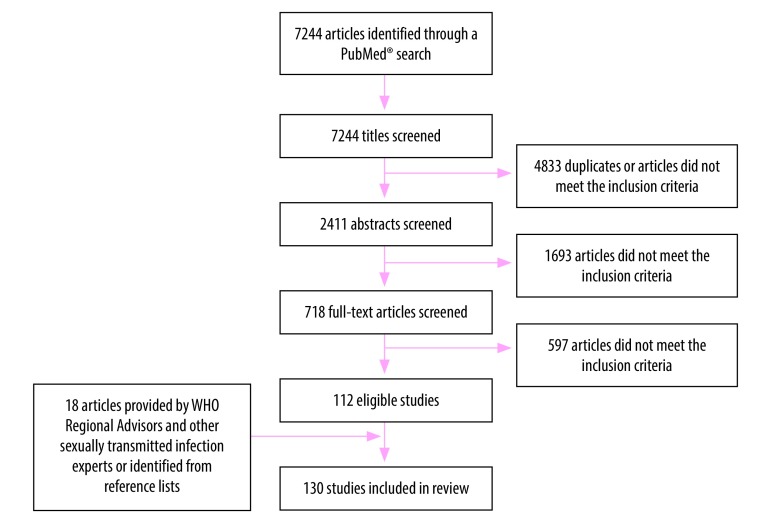

Of the 7244 articles screened, 112 studies met the inclusion criteria for one or more of the three infections (Fig. 1). We identified an additional 18 studies through expert consultations and reviewing reference lists (Nguyen M et al., Hanoi Medical University, Viet Nam, personal communication, 23 March 2018; El Kettani A et al., National Institute of Hygiene, Morocco, personal communication, 2 May 2016; Galdavadze K et al., Disease Control and Public Health, Republic of Georgia; personal communication, 22 August 2017).23–150 Of these 130 studies, 111 reported data for women only (Table 1; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/96/8/18-228486), three reported data for men only (Table 2; available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/96/8/18-228486) and 16 reported data for both women and men (Table 1 and Table 2). Only 34 studies in women and four studies in men provided information on all three infections. The included studies contained 100 data points in women for chlamydia, 64 for gonorrhoea and 69 for trichomoniasis. In men, there were 16 data points for chlamydia, 11 for gonorrhoea and seven for trichomoniasis (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the selection of studies for estimating the prevalence and incidence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis, 2016

WHO: World Health Organization.

Note: This figure does not include studies from North America; the North American estimates were based on published estimates.10,11

Table 1. Included studies on chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis prevalence in women, 2009–2016.

| Study, by WHO region | Country or territory and location | Date of study | Population and age, years | Chlamydia |

Gonorrhoea |

Trichomoniasis |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical specimen, testa | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | Clinical specimen, test | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | Clinical specimen, testa | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | ||||||

| African Region | ||||||||||||||

| Wynn et al., 201823 | Botswana, Gaborone | Jul 2015–May 2016 | ANC clinic attendees, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 400 | 7.8 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 400 | 1.3 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 400 | 5.3 | ||

| Ginindza et al., 201743 | Eswatini, nationalb | Jun–Jul 2015 | Outpatient clinic attendees, 15–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 655 | 5.8 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 655 | 5.3 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 655 | 7.8 | ||

| Eshete et al., 201324 | Ethiopia, Jimma Town | Dec 2011–May 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–36 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 361 | 5.0 | ||

| Mulu et al., 201525 | Ethiopia, Bahir Dar | May–Nov 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–49 | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture and Gram staina | 214 | 0.9 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 214 | 1.4 | ||

| Schönfeld et al., 201826 | Ethiopia, Asella | May 2014–Sep 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, point-of-care testb | 580 | 5.3 | ||

| Volker et al., 201727 | Ghana, Western region | Oct 2011–Jan 2012 | Attendees at a hospital maternity clinic, 14–48 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 177 | 1.7 | Genital fluid, culture | 180 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Jespers et al., 201428 | Kenya, Mombasa | 2010–2011 | Participants in a community survey, 18–35 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 110 | 3.6 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 110 | 0.9 | Genital fluid, culture | 110 | 2.7 | ||

| Kinuthia et al., 201529 | Kenya, Ahero and Bondo districts | May 2011–Jun 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, ≥ 14 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1276 | 5.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1276 | 2.5 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 1278 | 6.3 | ||

| Drake et al., 201330 | Kenya, Western Kenya | Pre-2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 14–21 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 537 | 4.7 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 537 | 1.7 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 537 | 5.6 | ||

| Masese et al., 201731 | Kenya, Mombasa | Aug 2014–Mar 2015 | Students, 15–24 | Urine, amplification test | 451 | 3.5 | Urine, amplification test | 451 | 1.6 | Urine, amplification test | 451 | 0.7 | ||

| Masha et al., 201732 | Kenya, Kilifi | Jul–Sep 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–45 | Urine, amplification test | 202 | 14.9 | Urine, amplification test | 202 | 1.0 | Genital fluid, culture | 202 | 7.4 | ||

| Nkhoma et al., 201733 | Malawi, Mangochi District | Feb 2011–Aug 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, ≥ 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 1210 | 10.5 | ||

| Olowe et al., 201434 | Nigeria, Osogba | Jul–Apr 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 100 | 2.0 | ||

| Etuketu et al., 201535 | Nigeria, Abeokutu | Jun–Jul 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–44 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 300 | 10.3 | ||

| Muvunyi et al., 201136 | Rwanda, Kigali | Nov 2007–Mar 2010 | Controls for infertility study, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 312 | 3.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Franceschi et al., 201637 | Rwanda, Kigali | Apr 2013–May 2014 | Students, 18–20 | Urine, amplification test | 912 | 2.2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Vieira-Baptista et al., 201738 | Sao Tome and Principe, Principe | 2015 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 21–60 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 100 | 3.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 100 | 2.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 100 | 8.0 | ||

| Moodley et al., 201539 | South Africa, Durban | May 2008–Jun 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1459 | 17.8 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1459 | 6.4 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1459 | 15.3 | ||

| Jespers et al., 201428 | South Africa, Johannesburg | 2010–2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 109 | 16.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 109 | 0.9 | Genital fluid, culture | 109 | 4.6 | ||

| Peters et al., 201440 | South Africa, Mopani District | Nov 2011–Feb 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 18–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 603 | 16.1 | Genital, amplification test | 603 | 10.1 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| de Waaij et al., 201741 | South Africa, Mopani District | Nov 2011–Feb 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 18–49 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 575 | 19.7 | ||

| Francis et al., 201842 | South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal | Oct 2016–Jan 2017 | Youth people, 15–24 | Genital, amplification test | 259 | 11.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 259 | 1.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 259 | 4.6 | ||

| Tchelougou et al., 201344 | Togo, Sokodé | Jun 2010–Aug 2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 302 | 3.6 | ||

| Donders et al., 201645 | Uganda, Kampala | Pre-2015 | Outpatient clinic attendees, adult | Genital fluid, amplification test | 360 | 1.4 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 360 | 1.7 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 360 | 6.7 | ||

| Rutherford et al., 201446 | Uganda, Kampala | Sep 2008–Apr 2009 | Students, 19–25 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 280 | 2.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 280 | 1.1 | Genital fluid, culture | 247 | 0.8 | ||

| de Walque et al., 201247 | United Republic of Tanzania, Kilombero and Ulanga Districts | Feb–Apr 2009 | Participants in HIV prevention trial, 18–30 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1204 | 2.7 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1204 | 1.4 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1204 | 16.2 | ||

| Chiduo et al., 201248 | United Republic of Tanzania, Tanga | May 2009–Oct 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–44 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 185 | 1.6 | Genital fluid, culture and Gram stain | 185 | 1.6 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 185 | 11.4 | ||

| Hokororo et al., 201549 | United Republic of Tanzania, Mwanza | Apr–Dec 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 14–20 | Urine, amplification test | 403 | 11.4 | Urine, amplification test | 403 | 6.7 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 403 | 13.4 | ||

| Lazenby et al., 201450 | United Republic of Tanzania, Arusha District | Pre-2014 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 30–60 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 324 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 324 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 297 | 10.4 | ||

| Maufi et al., 201851 | United Republic of Tanzania, Mwanza | Nov 2014–Apr 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, 17–46 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 365 | 10.4 | ||

| Chaponda et al., 201652 | Zambia, Nchelenge District | Nov 2013–Apr 2014 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1083 | 5.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1083 | 3.1 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1083 | 24.8 | ||

| Stephen et al., 201753 | Zimbabwe, Harare | Jan 2012–Apr 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 242 | 5.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Region of the Americas | ||||||||||||||

| Touzon et al., 201454 | Argentina, Buenos Aires | Jan 2010–Dec 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 1238 | 1.8 | ||

| Testardini et al., 201655 | Argentina, Buenos Aires | Apr 2010–Aug 2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 386 | 5.2 | ||

| Mucci et al., 201656 | Argentina, Buenos Aires | Aug 2012–Jan 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 10–42 | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 210 | 0.5 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 210 | 1.4 | ||

| Department of Public Health 201857 | Bahamas, national | 2016 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Urine, amplification test | 2504 | 12.0 | Urine, amplification test | 2504 | 2.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Magalhaes et al., 201558 | Brazil, Rio Grande do Norte State | 2008–2012 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 25–60 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1134 | 10.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Miranda et al., 201459 | Brazil, national | Mar–Nov 2009 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–24 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 299 | 7.7 | ||

| Pinto et al., 201160 | Brazil, national | Mar–Nov 2009 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–24 | Urine, amplification test | 2071 | 9.8 | Urine, amplification test | 2071 | 1.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ferreira et al., 201561 | Brazil, Belem and Para | 2009–2011 | ANC clinic attendees, < 19 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 168 | 16.7 | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 168 | 3.0 | ||

| Piazzetta et al., 201162 | Brazil, Curitiba | Pre-2011 | Sexually active youth people, 16–23 | Urine, amplification test | 335 | 10.7 | Urine, amplification test | 335 | 1.5 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Silveira MF et al., 201763 | Brazil, Pelotas | Dec 2011–May 2013 | Attendees at a hospital maternity clinic, 18–24 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 562 | 12.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Mesenburg et al., 201364 | Brazil, Pelotas | Dec 2011–Jan 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, < 30 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 361 | 15.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Gatti et al., 201765 | Brazil, Rio Grande | Jan 2012–Jan 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 204 | 5.9 | ||

| Marconi et al., 201566 | Brazil, Botucatu | Sep 2012–Jan 2013 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 14–54 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 1519 | 1.4 | ||

| Neves et al., 201667 | Brazil, Manaus | Oct 2012–Dec 2013 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 14–25 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1169 | 13.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Zamboni et al., 201668 | Brazil, Santiago | Mar 2013–Mar 2014 | Outpatient clinic attendees, 15–24 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 181 | 5.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Melo et al., 201669 | Brazil, Region of La Araucanía | 2013–2014 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 18–24 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 151 | 11.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Glehn et al., 201670 | Brazil, Federal District | Nov 2014–Mar 2015 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 18–49 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 193 | 15.5 | ||

| Ovalle et al., 201271 | Chile, Santiago | Apr 2010–Oct 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 255 | 5.9 | Genital fluid, culture | 255 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, culture | 255 | 2.4 | ||

| Huneeus et al., 201872 | Chile, Santiago | 2012–2014 | Sexually active youth people, < 25 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 171 | 8.8 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 171 | 0.6 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 171 | 0.0 | ||

| Villaseca et al., 201573 | Chile, Santiago | Jun 2013–Dec 2013 | Attendees at a family health clinic, 15–54 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 101 | 3.0 | ||

| Stella et al., 201174 | Colombia, rural Medellin | 2009–2010 | Students, 15–18 | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 262 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Paredes et al., 201575 | Colombia, Sabana Centro province | 2011 | Students, 14–19 | Urine, amplification test | 436 | 3.2 | Urine, amplification test | 436 | 0.2 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Giraldo-Ospina et al., 201576 | Colombia, Dosquebradas | Jun 2012–Aug 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–47 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 101 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, culture | 101 | 2.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ceron et al., 201477 | Colombia, Bogota | Aug–Dec. 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 15–40 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 226 | 5.3 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 226 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Jobe et al., 201478 | Haiti, Jérémie | Oct 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 16–75 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 199 | 11.6 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 199 | 4.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 199 | 19.6 | ||

| Jobe et al., 201478 | Haiti, Jérémie | Oct 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 19–78 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 104 | 1.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 104 | 1.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 104 | 13.5 | ||

| Scheildell et al., 201879 | Haiti, Gressier | Aug–Oct 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Urine, amplification test | 200 | 8.0 | Urine, amplification test | 200 | 3.0 | Urine, amplification test | 200 | 20.5 | ||

| Bristow et al., 201780 | Haiti, Port-au-Prince | Oct 2015–Jan 2016 | ANC clinic attendees, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 300 | 14.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 300 | 2.7 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 300 | 27.7 | ||

| Conde-Ferráez et al., 201781 | Mexico, Merida | Aug 2010–Jan 2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 121 | 8.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| López-Monteon et al., 201382 | Mexico, central Veracruz | Jun–Jul 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 14–50 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Urine, amplification test | 158 | 19.0 | ||

| Magana-Contreras et al., 201583 | Mexico, Villahermosa | Jan 2013–Nov 2014 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 16–74 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 201 | 1.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Casillas-Vega et al., 201784 | Mexico, Jalisco | Sep 2013–Aug 2014 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 287 | 10.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Cabeza et al., 201585 | Peru, Lima | Dec 2012–Jan 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, ≥ 16 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 600 | 10.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| van der Helm et al., 201386 | Suriname, Paramaribo | Mar 2008–Jul 2010 | Attendees at a family planning clinic, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 819 | 9.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| van der Helm et al., 201287 | Suriname, Paramaribo | Jul 2009–Feb 2010 | Attendees at a family planning clinic, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 753 | 9.2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| South-East Asia Region | ||||||||||||||

| Franceschi et al., 201637 | Bhutan, Thimpu and Paro | Sep 2013 | Students in an HPV vaccination study, 18–20 | Urine, amplification test | 973 | 3.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Vidwan et al., 201288 | India, Vellore | Apr 2009–Jan 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–45 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 784 | 0.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Vijaya Mn et al., 201389 | India, rural Bangalore | Oct 2010–Sep 2012 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, 25–46 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 750 | 2.1 | ||

| Kojima et al., 201890 | India, Mysore district | May 2011–Jun 2014 | ANC clinic attendees, young women | Genital fluid, amplification test | 213 | 0.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 213 | 0.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 213 | 6.1 | ||

| Shah et al., 201491 | India, Baroda | May 2011–Aug 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 20–35 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 233 | 3.4 | ||

| Krishnan et al., 201892 | India, Udupi district | Aug 2013–May 2015 | Community members, 18–65 | Urine, amplification test | 811 | 0.2 | Urine, amplification test | 811 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ani & Darmayani 201793 | Indonesia, Bali | Apr 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 376 | 7.4 | ||

| Banneheke et al., 201394 | Sri Lanka, Colombo district | 2007–2009 | Participants in diagnostic test study, 16–45 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 601 | 2.8 | ||

| European Region | ||||||||||||||

| Farr et al., 201695 | Austria, Vienna | Jan 2005–Jan 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, DNA probe-based assayc | 3763 | 0.8 | ||

| Ljubin-Sternak et al., 201796 | Croatia, Zagreb | Mar 2014–Feb 2015 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 8665 | 1.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Peuchant et al., 201597 | France, Bordeaux | Jan–Jun 2011 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–44 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1004 | 2.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1004 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Peuchant et al., 201597 | France, Bordeaux | Sep 2012–Feb 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, < 25 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 112 | 7.1 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 112 | 1.8 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Galdavadze et al., personal communication 2012 | Georgia, Tbilisi | Jul 2011–Mar 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 14–44 | Urine, amplification test | 300 | 5.0 | Urine, amplification test | 300 | 0.3 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ikonomidis et al., 201598 | Greece, Thessaly state | Feb 2012–Nov 2015 | Attendees at a urology and gynaecology clinic, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 130 | 0.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| O'Higgins et al., 201799 | Ireland, Dublin | Dec 2011–Dec 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, 16–25 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 2687 | 4.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Hassan et al., 2016100 | Ireland, Dublin | Jul 2014–Jan 2015 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 25–40 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 236 | 3.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 236 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Bianchi et al., 2016101 | Italy, Milan | Dec 2008–Dec 2012 | HPV vaccinated young women, 18–23 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 591 | 4.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Seraceni et al., 2016102 | Italy, north-eastern | Jan 2009–Dec 2014 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 921 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Panatto et al., 2015103 | Italy, Turin, Milan and Genoa | Jan–Jun 2010 | Women attending gynaecologic routine check-ups, 16–26 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 566 | 5.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Foschi et al., 2016104 | Italy, Bologna | Jan 2011–May 2014 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, routine, > 14 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 3072 | 3.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Matteelli et al., 2016105 | Italy, Brescia | Nov 2012–Mar 2013 | Sexually active students, ≥ 18 | Urine, amplification test | 1297 | 1.9 | Urine, amplification test | 1297 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Camporiondo et al., 2016106 | Italy, Rome | Mar 2013 | Healthy women attending screening, 34–60 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 309 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 309 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 309 | 1.3 | ||

| Leli et al., 2016107 | Italy, Perugia | Jan–Oct 2015 | Outpatient clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1487 | 1.3 | ||

| Gravningen et al., 2013108 | Norway, Finnmark | 2009 | Sexually active students, 15–20 | Urine, amplification test | 607 | 6.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Silva et al., 2013109 | Portugal, Porto | Pre-2013 | Students, 14–30 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 432 | 6.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Babinská et al., 2017110 | Slovakia, eastern parts | 2011 | Community members, adults | Urine, amplification test | 511 | 3.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Fernández-Benítez et al., 2013111 | Spain, Laviana and Asturias | Nov 2010–Dec 2011 | Sexually active youth people, 15–24 | Urine, amplification test | 277 | 4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Pineiro et al., 2016112 | Spain, Basque Autonomous Community | Jan 2011–Dec 2014 | Attendees at a hospital maternity clinic, 14–54 | Urine, amplification test | 11 687 | 1.0 | Urine, amplification test | 11 687 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Field et al., 2018113 | United Kingdom, national | Sep 2010–Aug 2012 | Sexually active adults, 16–44 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Urine, amplification test | 2559 | 0.3 | ||

| Sonnenberg et al., 2013114 | United Kingdom, national | Sep 2010–Aug 2012 | Sexually active adults, 16–44 | Urine, amplification test | 2665 | 2.3 | Urine, amplification test | 2665 | 0.1 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||||||||||

| Nada et al., 2015115 | Egypt, Cairo | Jan–Nov 2014 | Controls for infertility study, adult | Genital fluid, amplification test | 100 | 2.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Hassanzadeh et al., 2013116 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Shiraz | 2009–2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, amplification test | 1100 | 1.2 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Hamid et al., 2011117 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Zanjan province | Apr 2009 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, 15–45 | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 328 | 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Nourian et al., 2013118 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Zanjan | Jul 2009–Jun 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 1000 | 3.3 | ||

| Rasti et al., 2011119 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Kashan | Pre-2010 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 450 | 0.4 | ||

| Dehgan Marvast et al., 2017120 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Yazd | May–Sep 2010 | ANC clinic attendees, 16–39 | Urine, amplification test | 250 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ahmadi et al., 2016121 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Sanandaj | Aug 2012–Jan 2013 | Controls for spontaneous abortion study, 19–42 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 109 | 11.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Arbabi et al., 2014122 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Kashan | Oct 2012–Aug 2013 | Attendees at a public health unit, 16–60 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 970 | 2.3 | ||

| Hasanabad et al., 2013123 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Sabzevar | Pre-2013 | ANC clinic attendees, adolescents | Urine, amplification test | 399 | 12.3 | Urine, amplification test | 399 | 1.3 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Mousavi et al., 2014124 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Sanandai | Feb–May 2013 | Controls for infertility study, 14–40 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 104 | 5.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Nateghi Rostami et al., 2016125 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Qom | May 2013–Apr 2014 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, 18–50 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 518 | 7.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Marashi et al., 2014126 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), not specified | Pre-2014 | Controls for infertility study, 20–40 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 200 | 6.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Joolayi et al., 2017127 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Ahvaz | Aug 2016–Jan 2017 | Controls for infertility study, 18–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 125 | 1.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| El Kettani et al., personal communication, 2016 | Morocco, Rabat, Salé, Agadir and Fes | Oct 2011–Dec 2011 | Attendees at a family planning clinic, 18–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 537 | 3.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 537 | 0.4 | Genital, culture | 537 | 5.6 | ||

| El Kettani et al., personal communication, 2016 | Morocco, Rabat, Salé, Agadir and Fes | Dec 2011–Jan 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 252 | 3.6 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 252 | 0.8 | Genital fluid, culture | 252 | 5.2 | ||

| Kamel 2013128 | Saudi Arabia, Jazan | Jul 2011–Jun 2012 | Controls for infertility study, 18–40 | Genital fluid, culture | 100 | 4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||||||||||

| Wen 2013129 | China, Wuhu | 2010 | Sexually active adults, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 2010 | 6.6 | ||

| Lu et al., 2013130 | China, Shenzhen | 2011–2012 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 7892 | 5.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Xia et al., 2015131 | China, east, 16 cities | Jan–Dec 2011 | Attendees at an hospital maternity clinic, adults | Genital fluid, culture | 108 268 | 1.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Zhang et al., 2017132 | China, Shaanxi province | Jun 2012–Jan 2013 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 500 | 3.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Zhang et al., 2017133 | China, Beijing | Mar–Oct 2014 | Attendees at an obstetrics and gynaecology clinic, 20–70 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 953 | 2.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 953 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, microscopy | 953 | 1.7 | ||

| Imai et al., 2015134 | Japan, Miyazaki | Oct 2011–Feb 2012 | Students, > 18 | Urine, amplification test | 1183 | 3.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Suzuki et al., 2015135 | Japan, national | Oct 2013–Mar 2014 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 250 571 | 2.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ministry of Health 2017136 | Mongolia, national | 2016 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 69 278 | 0.5 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Corsenac et al., 2015137 | New Caledonia, national | Aug–Dec 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 18–49 | Urine, amplification test | 376 | 10.1 | Urine, amplification test | 376 | 3.5 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Unger et al., 2015138 | Papua New Guinea, Madang | Nov 2009–Aug 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, ≥ 16 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 674 | 4.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 674 | 8.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 674 | 21.8 | ||

| Wangnapi et al., 2015139 | Papua New Guinea, Madang | Feb 2011–Apr 2012 | ANC clinic attendees, 16–39 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 362 | 11.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 362 | 9.7 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 362 | 21.3 | ||

| Vallely et al., 2017140 | Papua New Guinea, four provinces | Dec 2011–Jan 2015 | ANC clinic attendees, 18–59 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 765 | 22.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 765 | 14.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 765 | 22.4 | ||

| Vallely et al., 2017140 | Papua New Guinea, four provinces | Dec 2011–Jan 2015 | Participants for cervical cancer screening, 18–59 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 614 | 7.5 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 614 | 8.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 614 | 15.0 | ||

| Badman et al., 2016141 | Papua New Guinea, Milne Bay | Aug–Dec 2014 | ANC clinic attendees, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 125 | 20.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 125 | 11.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 125 | 37.6 | ||

| Hahn et al., 2014142 | Republic of Korea, Seoul | Mar 2010–Apr 2011 | ANC clinic attendees, adults | Genital fluid, amplification test | 455 | 2.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 455 | 0.4 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 455 | 0.0 | ||

| Choe et al., 2012143 | Republic of Korea, Seoul | Mar–Dec 2010 | Attendees at a health examination clinic, 20–59 | Urine, amplification test | 805 | 3.2 | Urine, amplification test | 805 | 0.2 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Kim et al., 2011144 | Republic of Korea, Uijeongbu | Jul–Dec 2010 | Attendees at a check-up clinic, 20–60 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 279 | 3.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 279 | 0.4 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 279 | 2.5 | ||

| Kim et al., 2014145 | Republic of Korea, Seoul | Jan–Oct 2012 | Attendees at a health examination clinic, 25–81 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 405 | 1.2 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 405 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 405 | 0.2 | ||

| Marks et al., 2015146 | Solomon Islands, Honiara | Aug 2014 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 16–49 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 296 | 20.3 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 296 | 5.1 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Ton Nu et al., 2015147 | Viet Nam, Hue | Sep 2010–Jun 2012 | Attendees at a family planning clinic, adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, microscopy | 534 | 0.7 | ||

| Nguyen et al., personal communication, 2017 | Viet Nam, Hanoi | 2016–2017 | ANC clinic attendees, > 18 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 490 | 6.9 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 490 | 0.0 | Genital fluid, amplification test | 490 | 0.8 | ||

ANC: antenatal care; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; NR: not reported; WHO: World Health Organization.

a Studies that reported using both culture and Gram stain were assumed to have the same sensitivity and specificity values as culture.

b The study used an immunochromatographic capillary-flow enzyme immunoassay and we assumed a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 99%.

c The study used a nonamplified, nucleic acid probe-based test system and we assumed the same specific and sensitivity values as for a nucleic acid amplification test.

Table 2. Included studies on chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis prevalence in men, 2009–2016.

| Study, by WHO region | Country or territory and location | Date of study | Population and age, years | Chlamydia |

Gonorrhoea |

Trichomoniasis |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical specimen, testa | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | Clinical specimen, testa | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | Clinical specimen, testa | Sample size | Study prevalence, % | ||||||

| African Region | ||||||||||||||

| Francis et al., 201842 | South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal | Oct 2016–Jan 2017 | Community members, 15–24 | Urine, amplification test | 188 | 5.3 | Urine, amplification test | 188 | 1.6 | Urine, amplification test | 188 | 0.5 | ||

| Rutherford et al., 201446 | Uganda, Kampala | Sep 2008–Apr 2009 | Students, 19–25 | Urine, amplification test | 360 | 0.8 | Urine, amplification test | 360 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| de Walque et al., 201247 | United Republic of Tanzania, Kilombero and Ulanga districts | Feb–April 2009 | Participants in HIV prevention trial, 18–30 | Urine, amplification test | 1195 | 1.7 | Urine: amplification test | 1195 | 0.4 | Urine, amplification test | 1195 | 8.5 | ||

| Region of the Americas | ||||||||||||||

| Huneeus et al., 201872 | Chile, Santiago | 2012–2014 | Sexually active students, ≤ 24 | Urine, amplification test | 115 | 8.7 | Urine, amplification test | 115 | 0.0 | Urine, amplification test | 115 | 0.0 | ||

| Paredes et al., 201575 | Colombia, Sabana Centro province | 2011 | Students, 14–19 | Urine, amplification test | 536 | 1.1 | Urine, amplification test | 536 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| South-East Asia Region | ||||||||||||||

| Jatapai et al., 2013148 | Thailand, national | Nov 2008–May 2009 | Military recruits, 17–29 | Urine, amplification test | 2123 | 7.9 | Urine, amplification test | 2123 | 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| European Region | ||||||||||||||

| Sviben et al., 2015149 | Croatia, Zagreb | Pre-2014 | Controls in case-control study, 18–66 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Urine, amplification test | 200 | 2.0 | ||

| Ikonomidis et al., 201598 | Greece, Thessaly State | Feb 2012–Nov 2015 | Attendees at urology and gynaecology clinic, adult | Genital, amplification test | 171 | 0.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Matteelli et al., 2016105 | Italy, Brescia | Nov 2012–Mar 2013 | Sexually active students, > 18 | Urine, amplification test | 762 | 1.4 | Urine, amplification test | 762 | 0.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Gravningen et al., 2013108 | Norway, Finnmark | 2009 | Sexually active youth, 15–20 | Urine, amplification test | 505 | 3.4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Babinská et al., 2017110 | Slovakia, eastern parts | 2011 | Community members, adult | Urine, amplification test | 344 | 2.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Fernández-Benítez et al., 2013111 | Spain, Laviana and Asturias | Nov 2010–Dec 2011 | Sexually active youth, 15–24 | Urine, amplification test | 210 | 4.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Field et al., 2018113 | United Kingdom, national | Sep 2010–Aug 2012 | Sexually active adults, 16–44 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Urine, amplification test | 1827 | 0.0 | ||

| Sonnenberg et al., 2013114 | United Kingdom, national | Sep 2010–Aug 2012 | Sexually active adults, 16–44 | Urine, amplification test | 1885 | 1.9 | Urine, amplification test | 1885 | 0.1 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||||||||||

| Arbabi et al., 2014122 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Kashan | Oct 2012–Aug 2013 | Attendees at a public health unit, 16–60 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Genital fluid, culture | 233 | 0.9 | ||

| Yeganeh et al., 2013150 | Iran (Islamic Republic of), Tehran | Pre-2013 | Urology clinic attendees, 18–50 | Urine, amplification test | 100 | 4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||||||||||

| Corsenac et al., 2015137 | New Caledonia, national | Aug–Dec 2012 | Attendees at a primary health-care clinic, 18–49 | Urine, amplification test | 232 | 7.8 | Urine, amplification test | 232 | 3.4 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Choe et al., 2012143 | Republic of Korea, Seoul | Mar–Dec 2010 | Attendees at a health examination clinic, 20–59 | Urine, amplification test | 807 | 7.9 | Urine, amplification test | 807 | 0.6 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Kim et al., 2011144 | Republic of Korea, Uijeongbu | Jul–Dec 2010 | Attendees at a check-up clinic, 20–60 | Urine, amplification test | 430 | 6.7 | Urine, amplification test | 430 | 0.5 | Urine, amplification test | 430 | 0.2 | ||

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; NR: not reported; WHO: World Health Organization.

a Tests were either nucleic acid amplification test or culture.

Table 3. Number of data points that met the study inclusion criteria for the WHO 2016 prevalence estimates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis.

| Estimation region | No. of countries, territories and areas | Chlamydia |

Gonorrhoea |

Trichomoniasis |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women |

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

Men |

|||||||||||||

| No. of data points | No. of countries | No. of data points | No. of countries | No. of data points | No. of countries | No. of data points | No. of countries | No. of data points | No. of countries | No. of data points | No. of countries | |||||||

| Central, eastern and western sub-Saharan Africa | 41 | 16 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | 6 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Andean, central, southern and tropical Latin America and Caribbean | 42 | 25 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| High-income North America | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| North Africa and Middle East | 20 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Australasia and high-income Asia Pacific | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Western, central and eastern Europe and central Asia | 54 | 19 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Oceania | 14 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| South Asia | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| East Asia and south-east Asia | 15 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 205 | 100 | 43 | 16 | 15 | 64 | 32 | 11 | 10 | 69 | 29 | 7 | 7 | |||||

NA: not applicable; WHO: World Health Organization.

Note: Eight of the 112 studies with data for women had two separate data points (e.g. for different population groups).

For women, a total of 43 (21.0%) of 205 countries, territories and areas had one or more data points for chlamydia, 32 (15.6%) for gonorrhoea and 29 (14.1%) for trichomoniasis. For men, only 15 (7.3%) countries, territories and areas had one or more data points for chlamydia, 10 (4.9%) for gonorrhoea and 7 (3.4%) for trichomoniasis. For women there were sufficient data to generate summary estimates for chlamydia for the nine estimation regions, but not for gonorrhoea or trichomoniasis (Table 4).

Table 4. Approach used to generate 2016 regional estimates for chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis.

| Estimation region | Women |

Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia | Gonorrhoea | Trichomoniasis | Chlamydia | Gonorrhoea | Trichomoniasis | ||

| Central, eastern and western sub-Saharan Africa | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| Andean, central, southern and tropical Latin America and Caribbean | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Special casea | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| High-income North Americab | United States estimate for 2012 | United States estimate for 2008 | United States estimate for 2008 | United States estimate for 2012 | United States estimate for 2008 | United States estimate for 2008 | |

| North Africa and Middle East | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| Australasia and high-income Asia Pacific | Meta-analysis | Gonorrhoea to chlamydia ratio | Trichomoniasis to chlamydia ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| Western, central and eastern Europe and central Asia | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Trichomoniasis to chlamydia ratio | Meta-Analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| Oceania | Meta-analysis | Meta-analysis | Meta-Analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| South Asia | Meta-analysis | Gonorrhoea to chlamydia ratio | Trichomoniasis to chlamydia ratioc | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

| East Asia and south-east Asia | Meta-analysis | Gonorrhoea to chlamydia ratiod | Meta-analysis | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | Global male-to-female ratio | |

a In consultation with advisors on sexual transmitted infections for the World Health Organization (WHO) Region of the Americas, we decided to use the midpoint between the 2016 estimate generated by applying the global male-to-female ratio (7.5%) and the 2012 estimate for the region (2.1%). We deemed the former to be too high and the latter too low.

b Following discussions with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we based our estimates on the latest published United States national estimates21,22 and assumed they remained constant over time and that estimates for 15–39-year-old people could be extrapolated to the 15–49-year age range. We did not apply the adjustments used for other Regions in the WHO estimates process. The figures for the United States were also applied to Canada.

c The estimate based on the three available data points was over 4%, considerably higher than the 2012 estimate. Following discussions with regional experts we decided not to use this estimate, but instead to use the trichomoniasis to chlamydia ratio for low and lower middle-income countries, territories and areas.

d This estimation region is made up of countries from East Asia and South East Asia. We used the higher and upper-middle income gonorrhoea to chlamydia ratio for East Asia and the low and lower-middle income ratio for South East Asia.”

Syphilis

As of 2 May 2018, the Spectrum-STI Database contained 1576 data points from surveys conducted since 1990, including 978 from January 2009 to December 2016.151 In total, 181 (88.3%) of 205 countries, territories and areas had sufficient data to generate a Spectrum STI estimate for 2016. For the remaining 24 countries, territories and areas, we used the median value of the countries with data for the relevant WHO region as the 2016 estimate.

Prevalence and incidence estimates

Table 5 shows prevalence estimates for the WHO regions for 2016. Based on prevalence data from 2009 to 2016, the estimated pooled global prevalence of chlamydia in 15–49-year-old women was 3.8% (95% UI: 3.3–4.5) and in men 2.7% (95% UI: 1.9–3.7), with regional values ranging from 1.5 to 7.0% in women and 1.2 to 4.0% in men. For gonorrhoea, the global estimate was 0.9% (95% UI: 0.7–1.1) in women and 0.7% (95% UI: 0.5–1.1) in men, with regional values in women ranging from 0.3 to 1.9% and from 0.3 to 1.6% in men. The estimates for trichomoniasis were 5.3% (95% UI: 4.0–7.2) in women and 0.6% (95% UI: 0.4–0.9) in men, with regional values ranging from 1.6 to 11.7% in women and from 0.2 to 1.3% in men. For syphilis, the global estimate in both men and women was 0.5% (95% UI: 0.4–0.6) with regional values ranging from 0.1 to 1.6%. The WHO African Region had the highest prevalence for chlamydia in men, gonorrhoea in women and men, trichomoniasis in women and syphilis in men and women. The WHO Region of the Americas had the highest prevalence of chlamydia in women and of trichomoniasis in men.

Table 5. Comparison of 2012 and 2016 WHO regional prevalence estimates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis.

| WHO Region, by sex | Estimated prevalence, % (95% UI) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia |

Gonorrhoea |

Trichomoniasis |

Syphilis |

|||||||||

| 2012 | 2016 | 2012 | 2016 | 2012 | 2016 | 2012 | 2012 (updated) | 2016 | ||||

| Women | ||||||||||||

| African Region | 3.7 (2.7–5.2) | 5.0 (3.8–6.6) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) | 11.5 (9.0–14.6) | 11.7 (8.6–15.6) | 1.8 (1.4–2.5) | 1.7 (1.5–1.9) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | |||

| Region of the Americas | 7.6 (6.7–8.7) | 7.0 (5.8–8.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 7.7 (4.3–13.1) | 7.7 (5.1–11.5) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 0.7 (0.6–0.7) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | |||

| South-East Asia Region | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 1.5 (1.0–2.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 1.8 (1.1–2.7) | 2.5 (1.3–4.9) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | |||

| European Region | 2.2 (1.6–2.9) | 3.2 (2.5–4.2) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | |||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 3.5 (2.4–5.0) | 3.8 (2.6–5.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 5.9 (4.5–8.0) | 4.7 (3.3–6.7) | 0.5 (0.4–0.9) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | |||

| Western Pacific Region | 6.2 (5.1–7.5) | 4.3 (3.0–5.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 5.5 (3.3–8.9) | 5.6 (2.7–10.8) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | |||

| Global total | 4.2 (3.7–4.7) | 3.8 (3.3–4.5) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 5.0 (4.0–6.4) | 5.3 (4.0–7.2) | 0.4 (0.4–0.6) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | |||

| Men | ||||||||||||

| African Region | 2.5 (1.7–3.6) | 4.0 (2.4–6.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 1.6 (0.9–2.6) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) | 1.8 (1.1–2.8) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | |||

| Region of the Americas | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | 3.7 (2.1–5.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | |||

| South-East Asia Region | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.4) | |||

| European Region | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 2.2 (1.5–3.0) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | |||

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 2.7 (1.6–4.3) | 3.0 (1.7–4.8) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | |||

| Western Pacific Region | 5.2 (3.4–7.2) | 3.4 (2.0–5.3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | |||

| Global total | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) | 2.7 (1.9–3.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | |||

UI: uncertainty interval; WHO: World Health Organization.

Notes: The 2012 estimates are from Newman et al., 2015.6 For syphilis both the WHO estimate for 2012 and the 2018 updated 2012 estimate using Spectrum STI are shown.19 For chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis, the study inclusion window for 2016 was samples collected between 2009 and 2016, and for 2012, between 2005 and 2012.

These prevalence estimates correspond to the totals of 124.3 million cases of chlamydia, 30.6 million cases of gonorrhoea, 110.4 million cases of trichomoniasis and 19.9 million cases of syphilis (available from the data repository).13

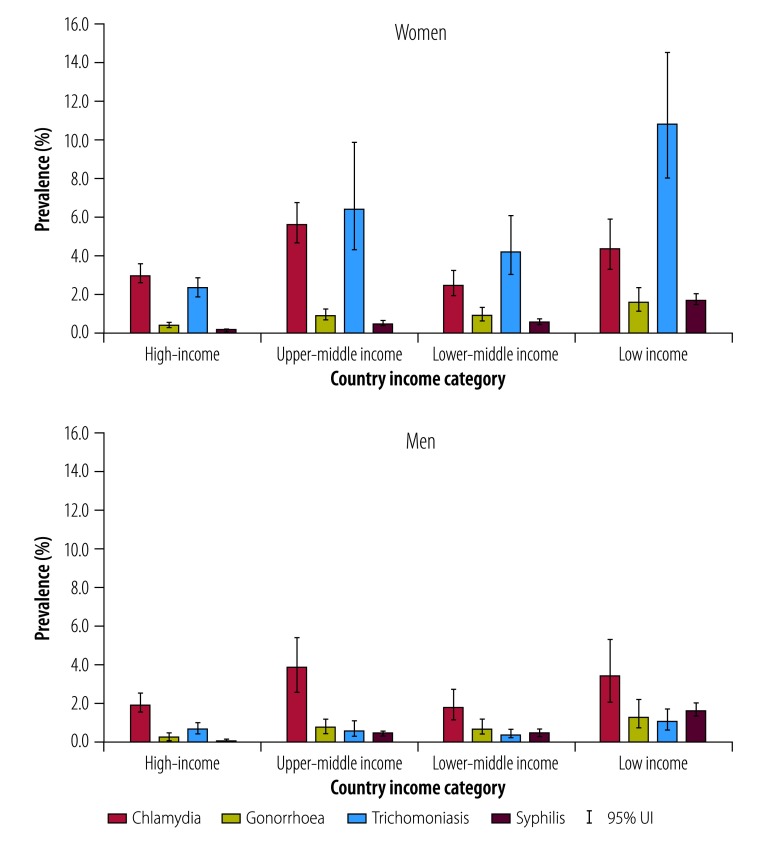

Using the World Bank classification, high-income countries, territories and areas had the lowest estimated prevalence, and low-income countries, territories and areas had the highest prevalence of gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis. For chlamydia, estimated prevalence was highest in upper-middle income countries, territories and areas (Fig. 2). The SDG grouping showed the highest prevalence of all four sexually transmitted infections in Oceania region, that is, Pacific island nations excluding Australia and New Zealand (available from the data repository).13

Fig. 2.

Prevalence estimates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis in adults, by World Bank classification, 2016

UI: uncertainty interval.

Notes: We defined adults as 15–49 years of age and used year 2016 income classification from the World Bank.17

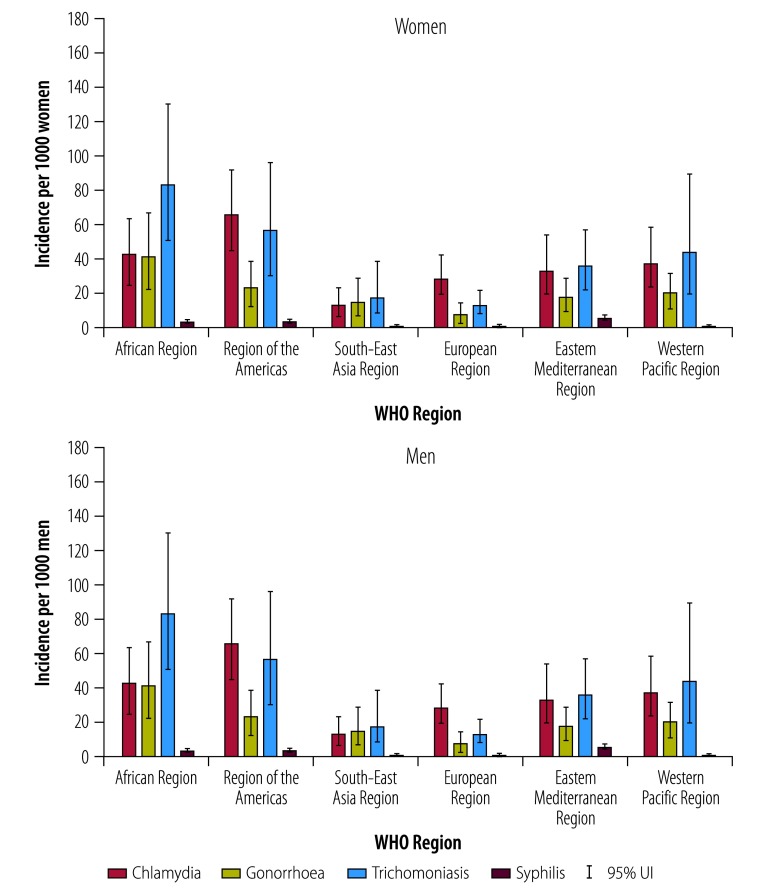

We estimated the global incidence rate for chlamydia in 2016 to be 34 cases per 1000 women (95% UI: 25–45) and 33 per 1000 men (95% UI: 21–48); for gonorrhoea 20 per 1000 women (95% UI: 14–28) and 26 per 1000 men (95% UI: 15–41); for trichomoniasis 40 per 1000 women (95% UI: 27–58) and 42 per 1000 men (95% UI: 23–69); and for syphilis 1.7 per 1000 women (95% UI: 1.4–2.0) and 1.6 per 1000 men (95% UI: 1.3–1.9; Fig. 3). The WHO Region of the Americas had the highest incidence rate for chlamydia and syphilis in both women and men, while the WHO African Region had the highest incidence rates for gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis in women and men. Incidence rates by income category and SDG regions are available from the data repository.13

Fig. 3.

Incidence rate estimates for chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis in adults, by WHO Region, 2016

UI: uncertainty interval, WHO: World Health Organization.

Note: We defined adults as 15–49 years of age.

These incidence rates translate globally into 127.2 million (95% UI: 95.1–165.9) new chlamydia cases, 86.9 million (95% UI: 58.6–123.4 million) gonorrhoea cases, 156.0 million (95% UI: 103.4–231.2 million) trichomoniasis cases and 6.3 million (95% UI: 5.5–7.1 million) syphilis cases in women and men aged 15–49 years in 2016. Together, the four infections accounted for 376.4 million new infections in 15–49-year-old people in 2016. Approximately 13.5% (50.8 million) of these infections occurred in low-income countries, territories and areas, 31.4% (118.1 million) in lower middle income, 47.1% (177.3 million) in upper-middle income and 8.0% (30.1 million) in high-income (available from the data repository).13

Comparison of estimates

Comparing the 2012 estimates with the estimates presented here shows that more data points were available in women for the 2016 estimates. The number increased from 69 to 100 for chlamydia, 50 to 64 for gonorrhoea and 44 to 69 for trichomoniasis. For men, the number of data points fell from 21 to 16 for chlamydia and from 12 to 11 for gonorrhoea, but increased from one to seven for trichomoniasis. The period of eligibility for both estimates was eight years with an overlap of four years (2009 to 2012); in women 27 data points were included in both estimates for chlamydia, 18 for gonorrhoea and 20 for trichomoniasis. In men, these overlaps were six, five and one, respectively.

Table 5 compares the 2012 and 2016 prevalence estimates for the four infections. For syphilis, two estimates are presented for 2012, the published estimate6 and the 2012 estimate generated using Spectrum STI and the latest Spectrum data set.19 For all infections in both women and men, the 2016 global prevalence estimate was within the 95% UI for 2012. At the regional level, the 95% UIs for prevalence overlapped for all four infections in both men and women, apart from gonorrhoea in men in the WHO African Region which was higher in 2016 than in 2012.

Discussion

We estimated a global total of 376.4 million new curable urogenital infections with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis in 15–49-year-old women and men in 2016. This estimate corresponds to an average of just over 1 million new infections each day. The number of individuals infected, however, is smaller as repeat infections and co-infections are common.152

The estimates of prevalence and incidence in 2016 were similar to those in 2012, both globally and by region, showing that sexually transmitted infections are persistently endemic worldwide. Grouping countries, territories and areas according to SDG regions revealed that the prevalence and incidence of all four sexually transmitted infections, in both women and men, were highest in the Oceania Region. The small island states in this SDG region are part of the WHO Western Pacific Region, which is dominated by China (owing to its population size). Therefore, the levels of sexually transmitted infections and need for infection control in these island states are masked when viewing the estimates only by WHO Region. When using the World Bank classification of countries, the prevalence of gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis were highest in low-income countries, territories and areas. The prevalence of chlamydia was highest in the upper middle-income countries, territories and areas, partly due to high estimates in some Latin American countries. Further research is needed to determine whether these estimates reflect methodological factors or differences in C. trachomatis transmission.

The 2016 estimates for chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomoniasis were based on a systematic review of the literature complemented by outreach to experts using the same methods as in 2012. The aim was to reduce bias and insure comprehensiveness in the search for data.19 For syphilis, the use of national estimates generated by a statistical model improves on the 2012 method by making use of historical trend data. The similarity between the published 2012 syphilis estimates and Spectrum STI generated estimates for 2012 provides reassurance about the validity of comparing the 2016 and 2012 estimates.

The study has limitations. First, limited prevalence data were available, despite an eight-year time window for data inclusion. Estimates for a given infection and region are therefore extrapolated from a small number of data points and ratios were used to generate estimates for some regions. For men, the lack of data was particularly striking. For syphilis, most data were from pregnant women, which might not reflect all women aged 15–49 years, or men. Second, the source studies include people in different age groups and used a range of diagnostic tests, so adjustment factors were applied to standardize measures across studies. Third, owing to the absence of empirical studies, incidence estimates were derived from the relationship between prevalence and duration of infection, and data on the average duration of infection for each of the four infections are also limited. Finally, because only studies among the general population were used, the prevalence and incidence in areas where key populations contribute disproportionately to sexually transmitted infection epidemics may have been underestimated despite the applied correction factor. These limitations have been discussed previously in detail.6

This study has implications for sexually transmitted infection programming and research. The quantity and quality of prevalence and incidence studies for sexually transmitted infections in representative samples of the general population, for both women and men, need improvement. Identifying opportunities to integrate data collection with clinical care platforms, such as HIV, adolescent, maternal, family planning and immunization is crucial. The recently developed WHO protocol for assessing the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in antenatal care settings153 provides a framework and consistent methods that can be adapted for women and men. Comparing data across studies requires better understanding of the performance characteristics of diagnostic tests, and implications for estimates of the average duration of infection for each infection. The processes for producing future prevalence estimates could be made timelier and more efficient through continually updated systematic reviews,154 as well as technological solutions that automate searching of databases and facilitate high quality updates of reviews.

The global estimates of prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections are important in the broader global context, highlighting a continuing public health challenge. Prevalence and incidence data play an important role in the design and evaluation of programmes and interventions for sexually transmitted infections and in interpreting changes in HIV epidemiology. The global threat of antimicrobial resistance, particularly the emergence of N. gonorrhoeae resistance to the few remaining antimicrobials recommended for treatment, further highlights the importance of investing in monitoring prevalence and incidence.155 Estimates of prevalence and incidence are essential for calculations of the burden of disease due to sexually transmitted infections, which are needed to advocate for funding to support sexually transmitted infection programmes. These burden estimates can also be used to promote innovation for point-of-care diagnostics, new therapeutics, vaccines and microbicides. The WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Sexually Transmitted Infections sets a target of 90% reductions in the incidence of gonorrhoea and of syphilis, globally, between 2018 and 2030.9 Major scale-ups of prevention, testing, treatment and partner services will be required to achieve these goals. The estimates generated in this paper, despite their limitations, provide an initial baseline for monitoring progress towards these ambitious targets.

Acknowledgements

We thank the WHO regional advisors and technical experts: Monica Alonso, Maeve Brito de Mello, Massimo Ghidinelli, Joumana Hermez, Naoko Ishikawa, Linh-Vi Le, Morkor Newman, Takeshi Nishijiima, Innocent Nuwagira, Leopold Ouedraogo, Bharat Rewari, Ahmed Sabry, Sanni Saliyou, Annemarie Stengaard, Ellen Thom and Motoyuki Tsuboi. We also thank Mary Kamb, S. Guy Mahiané, Otilia Mardh, Nico Nagelkerke, Gianfranco Spiteri, Igor Toskin, Teodora Wi, Nalinka Saman Wijesooriya and Rebecca Williams.

Funding:

This work was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the United Kingdom Department for International Development, and the World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. LJA and AS acknowledge support of Qatar National Research Fund (NPRP 9-040-3-008) that provided funding for collating data provided to this study.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Gerbase AC, Rowley JT, Heymann DH, Berkley SF, Piot P. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex Transm Infect. 1998. June;74 Suppl 1:S12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: overview and estimates. Report No.: WHO/HIV_AIDS/2001.02. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/who_hiv_aids_2001.02.pdf [cited 2018 Nov 5].

- 3.Prevalence and incidence of selected sexually transmitted infections, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, syphilis, and Trichomonas vaginalis: methods and results used by WHO to generate 2005 estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241502450/en/ [cited 2018 Nov 5].