Abstract

Background

Work histories generally cover all jobs held for ≥1 year. However, it may be time and cost prohibitive to conduct a detailed exposure assessment for each such job. While disregarding short-term jobs can reduce the assessment burden, this can be problematic if those jobs contribute important exposure information towards understanding disease aetiology.

Objective

To characterize short-term jobs, defined as lasting more than 1 year, but less than 2 years, in a population-based study conducted in Montreal, Canada.

Methods

In 2005–2012, we collected work histories for some 4000 participants in a case-control study of prostate cancer. Overall, subjects had held 19 462 paid jobs lasting ≥1 year, including 3655 short-term jobs. Using information from interviews and from the Canadian Classification and Dictionary of Occupations, we characterized short-term jobs and compared them to jobs held ≥2 years.

Results

Short-term jobs represented <4% of subjects’ work years on average. Forty-five per cent of subjects had at least one short-term job; of these, 49% had one, 24% had two, and 27% had at least three. Half of all short-term jobs had been held before the age of 24. Short-term jobs entailed more often exposure to fumes, odours, dust, and/or poor ventilation than longer jobs (17 versus 13%), as well as outdoor work (10 versus 5%) and heavy physical activity (16 versus 12%).

Conclusions

Short-term jobs occurred often in early careers and more frequently entailed potentially hazardous exposures than longer-held jobs. However, as they represented a small proportion of work years, excluding them should have a marginal impact on lifetime exposure assessment.

Keywords: case-control studies, retrospective exposure assessment, short-term employment

Introduction

The case-by-case expert assessment approach remains one of the most popular retrospective exposure assessment methods in population-based epidemiologic studies (Ge et al., 2018). This approach rests on the collection of detailed descriptions of all jobs held for each subject, which are then reviewed by one or more industrial hygienists, chemists, and/or occupational physicians who assign exposure estimates to a checklist of chemical and/or physical agents. While the case-by-case expert approach has been considered the reference method in population-based studies in the absence of measurement data (Bouyer and Hémon, 1993; Bourgkard et al., 2013), it represents a time-, cost-, and labour-intensive process, especially for large study sizes. Quantitative job-exposure matrices applicable to population-based studies represent an important development in assessing exposures (e.g. Peters et al., 2016). Nevertheless, such job-exposure matrices have only been developed for a limited number of agents. The expert-based methodologies can represent the only feasible approach for exploring associations across a large number of agents, for less prevalent agents, or for unusual exposure scenarios.

In a recent population-based study of prostate cancer, one strategy used to reduce the data collection and exposure assessment burden was to restrict the assessment to jobs held for at least 2 years and to disregard ‘short-term’ jobs held for less than 2 years. However, this strategy can be problematic if those short-term jobs contribute important exposure information towards understanding disease aetiology. To this end, we aimed to characterize short-term jobs, which we defined as lasting more than one year, but less than two years, in the context of this study.

Methods

Study population and data collection

The Prostate Cancer and Environment Study (PROtEuS) is a population-based case-control study of prostate cancer conducted in Montreal, Canada, and has been described in detail elsewhere (Sauvé et al., 2016; Blanc-Lapierre et al., 2018). Briefly, approximately 4000 participants were recruited in PROtEuS between 2005 and 2012. A complete work history covering all jobs held during lifetime was elicited during in-person interviews using a semi-structured questionnaire. Participants were on average 65 years old (standard deviation = 7 years) at diagnosis/interview. For jobs held ≥2 years, subjects provided a detailed description in a six-page questionnaire covering workplace characteristics, tasks, products and equipment used, and protective measures. Supplementary specialized questionnaires (n = 32) were used to collect additional information on tasks and processes for selected occupations. For jobs held for more than 1 year, but less than 2 years, data collection was limited to job title and a few words summarizing duties performed. We did not collect information for jobs held for 1 year or less.

Exposure assessment

For all jobs held for more than 1 year, a team of experts assigned standardized job titles based on the Canadian Classification and Dictionary of Occupations (CCDO) (Department of Employment and Immigration, 1971). The CCDO has four-level hierarchical structure. At its most precise level (seven-digit codes), the CCDO comprises over 7000 unique occupations. For most occupations, the documentation provides an overview of several qualification profiles and job characteristics, such as learning skills required, physical demands, and environmental conditions.

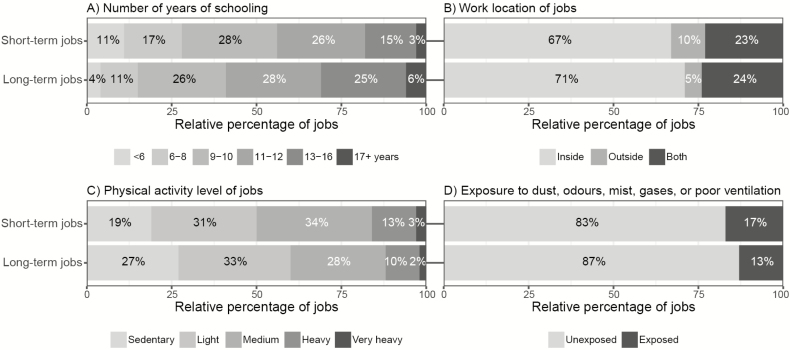

For the purposes of this comparison, we assigned for each short- or long-term job the following four characteristics based on the occupation title: (i) the approximate duration of schooling required (less than 6 years, 6–8 years, 9–10 years, 11–12 years, 13–16 years, 17 years or more), (ii) the physical activity strength (sedentary, light, medium, heavy, or very heavy work); (iii) the work location (indoor, outdoor, or both); (iv) the potential for exposure to fumes, odours, dust, mists, gases, and/or poor ventilation. We then compared the relative distribution of short- and long-term jobs for each of these four characteristics. For 13% of jobs, the CCDO documentation did not provide information about the characteristics.

Results

Distribution of short jobs in the study population

Overall, there were 3655 short-term jobs identified, held by 1767 study participants (45% out of 3961 subjects). Forty-nine per cent of those subjects had only held one short job, 24% had two, and 27% had three or more short-term jobs. Among subjects that held at least one short-term job, the median cumulative duration of the short-term jobs was 2 years (interquartile interval 1–3 years). Only nine subjects had held short-term jobs for 10 or more years. Short-term jobs represented less than 4% of work years on average. Fifty-one per cent of all short-term jobs were held before the age of 24 and another 25% were held between 25–34 years of age. Younger subjects tended to have a higher proportion of all jobs held being short-term jobs, but the differences between the age group categories was relatively small. The main difference between groups lied in ever having a short-term job, which was more frequent in younger subjects. For example, 57% of all subjects aged between 51 and 55 years old had at least one short-term job in their career compared to 41% for subjects aged between 66 and 70 years old.

Subjects holding short-term jobs were of various ancestries: 71% French, 16% other European, 6% African, 3% Middle Eastern, 2% Latin American, 2% Asian, and 1% others. Overall, 8% of all jobs were held outside of Canada. We were not able to ascertain the location of three jobs held by a subject who did not report his arrival date in Canada. The proportion of all jobs held outside of Canada that were short-term (20%) was similar to that of jobs held in Canada (19%).

Characteristics of short-term jobs

Compared to long-term jobs (n = 15 806), a higher proportion of short-term jobs were found in occupations related to services (14 versus 10%), clerical work (12 versus 9%), construction (8 versus 7%), processing (6 versus 4%), and material handling (4 versus 3%) (Table 1). Conversely, there were fewer short-term jobs in managerial and administrative occupations (7 versus 15%), transport equipment operating (4 versus 5%), and teaching (4 versus 5%).

Table 1.

Distribution of long- and short-term jobs by major occupation group

| Major occupation group (two-digit CCDO codes) | Long-term jobs (n = 15 806) | Short-term jobs (n = 3655) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| 11: Managerial, administrative, and related occupations | 2359 | 14.9 | 248 | 6.8 |

| 51: Sales occupations | 1618 | 10.2 | 344 | 9.4 |

| 85: Product fabricating, assembling, and repairing occupations | 1611 | 10.2 | 401 | 11.0 |

| 61: Service occupations | 1503 | 9.5 | 510 | 14.0 |

| 41: Clerical and related occupations | 1441 | 9.1 | 450 | 12.3 |

| 87: Construction trades occupations | 1174 | 7.4 | 300 | 8.2 |

| 21: Occupations in natural sciences, engineering, and mathematics | 1033 | 6.5 | 222 | 6.1 |

| 91: Transport equipment operating occupations | 828 | 5.2 | 139 | 3.8 |

| 27: Teaching and related occupations | 803 | 5.1 | 132 | 3.6 |

| 81/82: Processing occupations | 632 | 4.0 | 224 | 6.1 |

| 83: Machining and related occupations | 610 | 3.9 | 163 | 4.5 |

| 93: Material-handling and related occupations, n.e.c. | 417 | 2.6 | 142 | 3.9 |

| 33: Artistic, literary, performing arts, and related occupations | 386 | 2.4 | 65 | 1.8 |

| 23: Occupations in social sciences, and related fields | 356 | 2.3 | 82 | 2.2 |

| 31: Occupations in medicine and health | 291 | 1.8 | 37 | 1.0 |

| 95: Other crafts and equipment operating occupations | 274 | 1.7 | 46 | 1.3 |

| 71: Farming. Horticultural and animal-husbandry occupations | 214 | 1.4 | 49 | 1.3 |

| 75: Forestry and logging occupations | 70 | <1 | 33 | <1 |

| 25: Occupations in religion | 57 | <1 | 8 | <1 |

| 37: Occupations in sport and recreation | 48 | <1 | 15 | <1 |

| 99: Occupations not elsewhere classified | 45 | <1 | 23 | <1 |

| 77: Mining and quarrying including oil and gas field occupations | 29 | <1 | 21 | <1 |

| 73: Fishing, trapping, and related occupations | 7 | <1 | 1 | <1 |

Figure 1 presents a comparison of the distribution of selected characteristics of short- and long-term jobs held by the study participants, restricted to occupations for which these characteristics were provided in the official documentation of the occupational classification. Short-term jobs generally required lower educational attainment, with 28% of all short-term jobs requiring 8 years of schooling or less compared to 15% for long-term jobs. Short-term jobs were also more likely to require heavy or very heavy physical activity (16 versus 12%) and were twice likely to entail outdoor work than long-term jobs (10 versus 5%). Lastly, short-term jobs entailed more often exposure to fumes, odours, dust, and/or poor ventilation than longer jobs (17 versus 13%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of selected characteristics of short-term (n =3168) and long-term (n = 13 790) jobs.

Discussion

The evaluation of short-term jobs in occupational epidemiology has generally been restricted to industrial cohort studies, as subjects with short jobs may have differences in lifestyle factors and medical history compared to longer-tenured members of the cohort (e.g. Stewart et al., 1990; Kolstad and Olsen, 1999). To our knowledge, this represents one of the first comprehensive evaluations of short-term jobs within the context of a population-based case-control study.

Overall, less than half of all subjects reported having held at least one short job, and these represented a very small proportion of the subjects’ careers on average. Moreover, while short-term jobs more often involved outdoor work, higher physical exertion, and were more frequently exposed to chemical and/or physical agents, the differences with long-term jobs were relatively small. Based on this evaluation, disregarding these jobs from the overall assessment should have a negligible impact on cumulative exposure in our study. However, based on the observation that short-term jobs tended to occur at younger ages, early exposures (e.g. asbestos exposure during construction work) could be important for diseases with a long latency.

Our evaluation has some limitations. First, the coding of job titles for short-term jobs was based on a short description which may have a greater potential for misclassification compared to long-term jobs that used extensive questionnaires. Second, as a detailed assessment of specific exposures was not conducted for short-term jobs, our comparisons used relatively crude surrogates of exposure. Thus, we could not assess the impacts of excluding short-term jobs on cumulative exposure, or cumulative duration of exposure, to specific agents.

Lastly, there are some instances where the assessment of short-term jobs is desirable. This includes investigating diseases affecting younger adults, where short-term jobs may represent a comparatively larger proportion of subjects’ careers than in our study, which were 65 years old on average at interview. The detailed assessment of short jobs can also be critical for diseases where the exposure window is important, such as in investigating associations between birth outcomes and occupational exposures during pregnancy (e.g. Cordier et al., 1997; Lupo et al., 2012) or for identifying asthmagens in the workplace (Dumas et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Louise Nadon, Ramzan Lakhani, Mounia Senhaji Rhazi, and Robert Bourbonnais who carried out the occupational coding in PROtEuS.

Funding support for PROtEuS was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant no. PJT-159704), the Canadian Cancer Society (grants no. 13149, 19500, 19864, 19865), the Cancer Research Society, the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé, Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé—Réseau de Recherche en Santé Environnementale, and the Ministère du Développement économique, de l’Innovation et de l’Exportation du Québec. M.E.P. and J.F.S. received career awards and a fellowship, respectively, from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Blanc-Lapierre A, Sauvé JF, Parent ME (2018) Occupational exposure to benzene, toluene, xylene and styrene and risk of prostate cancer in a population-based study. Occup Environ Med; 75: 562–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgkard E, Wild P, Gonzalez M et al. (2013) Comparison of exposure assessment methods in a lung cancer case-control study: performance of a lifelong task-based questionnaire for asbestos and PAHs. Occup Environ Med; 70: 884–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer J, Hémon D (1993) Retrospective evaluation of occupational exposures in population-based case-control studies: general overview with special attention to job exposure matrices. Int J Epidemiol; 22 (Suppl. 2): S57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier S, Bergeret A, Goujard J et al. (1997) Congenital malformation and maternal occupational exposure to glycol ethers. Occupational exposure and congenital malformations working group. Epidemiology; 8: 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Employment and Immigration (1971) Canadian classification dictionary of occupations. Vol. 1 Ottawa, Canada: Department of Employment and Immigration. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas O, Donnay C, Heederik DJ et al. (2012) Occupational exposure to cleaning products and asthma in hospital workers. Occup Environ Med; 69: 883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge CB, Friesen MC, Kromhout H et al. (2018) Use and reliability of exposure assessment methods in occupational case-control studies in the general population: past, present, and future. Ann Work Expo Health; 62: 1047–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad HA, Olsen J (1999) Why do short term workers have high mortality? Am J Epidemiol; 149: 347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo PJ, Langlois PH, Reefhuis J et al. ; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. (2012) Maternal occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: effects on gastroschisis among offspring in the national birth defects prevention study. Environ Health Perspect; 120: 910–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S, Vermeulen R, Portengen L et al. (2016) SYN-JEM: a quantitative job-exposure matrix for five lung carcinogens. Ann Occup Hyg; 60: 795–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé JF, Lavoué J, Parent MÉ (2016) Occupation, industry, and the risk of prostate cancer: a case-control study in Montréal, Canada. Environ Health; 15: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PA, Schairer C, Blair A (1990) Comparison of jobs, exposures, and mortality risks for short-term and long-term workers. J Occup Med; 32: 703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]