Abstract

Using a framework of ecological systems theory and Black feminist theory, this article provides a conceptual exploration of barriers and facilitators to HIV risk communication between African American parents and daughters. African American female adolescents are disproportionately diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and are more likely to engage in sexually risky behaviors, which increases their risk of contracting HIV. Researchers have documented the importance of parental beliefs, knowledge, and communication about sexual and HIV risk as a protective factor in influencing safe sexual behavior in their daughters. By incorporating the ecological influences that affect familial processes among African American parents, in addition to highlighting Black feminist concepts, this article proposes a racial and gender-specific theoretical model to guide future family-based HIV prevention interventions.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Black feminism, ecological systems, parenting, African American adolescents

Background

African American female adolescents are at increased risk of contracting HIV compared with female adolescents of other racial and ethnic groups. This increased risk arose from the multiple contextual factors of sociohistorical trauma, sexual exploitation of African American women, and lack of community resources in the neighborhoods where African American female adolescents primarily reside (P. H. Collins, 2000; Wallace, Townsend, Glasgow, & Ojie, 2011). Compared with other ethnic groups, African American female adolescents are also more likely to have an early sexual debut, have multiple sexual partners, and engage in risky sexual behaviors such as not using a condom or engaging in sex while under the influence of drugs and alcohol (Jackson, Seth, DiClemente, & Lin, 2015). High-risk sexual behavior is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among African American female adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013a). Of African American female adolescents (aged 14–19 years), 44% have had at least one sexually transmitted disease (STD; CDC, 2013b). Consequently, adolescents exposed to an STD have a higher chance of contracting HIV, due to repetitious behaviors and community influences (Raiford, Seth, & DiClemente, 2013). African American adolescents often learn about sexual behaviors from peers, their community, and family (Aronowitz, Rennells, & Todd, 2006). Because they tend to live in socioeconomically disorganized neighborhoods and are more likely to obtain sexual partners from their direct environment, which often lack resources in reducing HIV risk, they are at a heightened disadvantage and at greater risk of contracting HIV (M. L. Collins, Baiardi, Tate, & Rouen, 2015; Floyd & Brown, 2013).

Parental Influence on Sexual Behavior in Female Adolescents

Understanding the context of parental influence on the sexual behaviors of African American female adolescents can prove to be beneficial in alleviating risk. The most effective family processes that have been shown to reduce HIV risk are (a) parent-child closeness (Murphy, Roberts, & Herbeck, 2012), (b) parental monitoring (Bettinger et al., 2004; Romer et al., 1999), (c) parental modeling (Whitbeck, Simons, & Kao, 1994), (d) parental disapproval (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; Khurana & Cooksey, 2012), and (e) parent-child sexual-risk communication (Cederbaum, Hutchinson, Duan, & Jemmott, 2013; Guilamo-Ramos, Lee, & Jaccard, 2016). However, no identified processes contribute individually to sexual-risk reduction without parent-child communication, which is most crucial (Hutchinson, Jemmott, Sweet Jemmott, Braverman, & Fong, 2003). Without sexual risk communication, parental monitoring and parental beliefs regard sexual behavior have no relationship with sexually risky behavior in adolescent females (Romer et al., 1999).

The temporal relationship of parent sexual-risk communication with daughters is also important to reduce adolescent sexual-risk behavior. Research with high-risk minority adolescents demonstrated that parent-adolescent discussions about sex are most effective when they occur before the first sexual encounter (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2016; Hutchinson et al., 2003). Beyond direct effects on adolescent sexual behavior, parent-adolescent communication about sex relates to mediating variables such as attitudes about HIV (Cederbaum et al., 2013), abstinence values (Miller, Forehand, & Kotchick, 1999), and intentions to abstain (Miller, Clark, & Moore, 1997). Also, such communication moderates relationships between other variables and adolescent sexual activity such as peer norms, which align strongly with sexual behavior for adolescents who did not discuss sex or condoms with their parents (Holman & Kellas, 2015).

Barriers to Parent-Daughter Communication in African American Families

Studies have identified common barriers that prevent parents from engaging in sexual-risk communication with their daughters: (a) self-efficacy, (b) parent-daughter closeness, (c) lack of HIV/AIDS and STD knowledge, (d) lack of effective strategies to avoid risky sexual behavior, and (e) parental beliefs (Dilorio et al., 2001; Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Dittus, & Gonzalez, 2008; Jaccard, Dittus, & Gordon, 2000; Wilson, Dalberth, Koo, & Gard, 2010). Adolescents who are more likely to receive information regarding sex from their peers, community, and media instead of their parents risk receiving false information about sex.

Intervention programs that incorporate family-based community work have shown that adolescents’ improved knowledge about sexual risk lead to fewer sexually risky behaviors (Aronowitz et al., 2006; Dittus, Miller, Kotchick, & Forehand, 2004; Hutchinson et al., 2003). In addition, studies examining parents who have successfully discussed sexual risk with their daughters described strategies to overcome barriers such as reading to enhance knowledge, asking their children about topics covered in their sex-education classes, and using events from their community, news broadcasts, and television shows to initiate conversations (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006; Rosenthal, Feldman, & Edwards, 1998).

In examining parent-daughter HIV risk communication for African American female adolescents, the theoretical model proposed is comprised of two theories: ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986) and Black feminist theory (Combahee River Collective, 1979; Davis, 1981; hooks, 1984). Both theories aid in examining contextual and sociohistorical factors that have shaped African American female adolescents’ susceptibility to HIV and the impact of family processes that lead to increased HIV risk in African American female adolescents.

Theoretical Framework

Ecological Systems Theory

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979, 1986) ecological systems model does not describe family processes, rather, it provides a framework on how external systems and environments influence family processes. Incorporating ecological systems theory aids in understanding not only HIV susceptibility in African American female adolescents but also how contextual factors shape parental processes that can impede parent-child sexual-risk communication. External influences can affect families’ capacity to foster the healthy development of children. The context of individual development can expand to family development in that the individual is involved in five interrelated environmental systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986)

The microsystem is a pattern of activities, social roles, interpersonal relations, and adolescent experiences in a given face-to-face setting with physical, social, and symbolic features (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986). In human development and family science, the family is primarily nested in the microsystem. The mesosystem has interlocking systems of microsystems and processes in two or more settings surrounding the developing adolescent. Examples involve relations between school and home, school and neighborhood/community, and family and peers, nested in the mesosystem. The exosystem comprises linkages and processes between two or more settings, at least one of which does not contain the child but indirectly influences processes in the immediate setting of the child, such as a parent’s loss of employment, working long hours, or loss of housing. Exosystem disruptions can affect family processes identified to shape sexual behavior in adolescent females (Hutchinson et al., 2003). The immediate environment, such as neighborhood, also influences parental processes including parental monitoring and supervision, parental warmth, and parental harshness and control (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006). Differences in parenting practices as a function of neighborhood of residence such that parents living in low-income and hazardous neighborhoods are more likely to use restrictive parenting practices and less parental warmth than parents living in middle-income or affluent neighborhoods where children have less adverse behavioral outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000).

The macrosystem consists of all systems shaped by beliefs, historical events, community resources, and cultural values of the overarching society and affect the healthy development of African American female adolescents. The U.S. macrosystem includes slavery and historical roots in racism that contribute to the inequities that African American families face which increase HIV risk: (a) lack of quality health care access, resulting in health disparities; (b) financial and economic inequalities; and (c) educational disparities. The chronosystem involves the influence of changes and continuities over time (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). Normative (school entry, puberty, entering the labor force, marriage, retirement) and nonnormative (death or severe illness in the family, divorce, moving to a new neighborhood, war) transitions can indirectly influence family processes. In shaping sexual behavior in African American adolescents, normative transitions, such as puberty, affect how female adolescents are viewed, leading them to feel pressured to engage in sexual behaviors before feeling adequately prepared.

Limitations of Ecological Systems

The lived experiences of African American female adolescents and women are so unique that even a macrolevel theory such as ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986) needs modification to effectively address the complex nature of the phenomena. It is essential to use a theory that acknowledges the heterogeneity in African American female adolescents, acknowledges their lived experiences, enhances parent-daughter sexual-risk communication, and addresses HIV risk susceptibility in this population.

Viewing the phenomena through an ecological systems lens brings attention to the larger context of multiple systems that affect African American female adolescents and their families. Historically in family science, feminist theorists argued that theoretical frameworks typically neglect or distort women’s experiences in families (Acker, 1973; Boss, Doherty, LaRossa, Schumm, & Steinmetz, 2004). Feminist theorists noted that mainstream theoretical approaches either ignore or put forth problematic conceptualizations of power, and family science pays insufficient attention to sociocultural and historical contexts (Boss et al., 2004, p. 600). Due to conflicts in feminism and family science, incorporating ecological systems theory and feminist theory aids in acknowledging the lived experiences of female adolescents, women, and historical events that have contributed to their marginalized status.

Black Feminist Theory

In examining the lived experiences of African American female adolescents, it is important to understand the historical and sociocultural contexts that have shaped the views of African American women. Output derived from Black feminist theory allows women to critically examine HIV susceptibility in African American female adolescents (Lavee & Dollahite, 1991). A Black feminist theoretical framework provides a sociohistorical lens to the experiences of African American female adolescents and their families. Black feminist theory is grounded in five core constructs: (a) acknowledging Black women’s historical struggle against multiple oppressions; (b) acknowledging that Black women and their families consistently negotiate the intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and class; (c) eradicating malignant images of Black womanhood; (d) incorporating activist perspectives into research by cocreating knowledge with informants and consciousness raising; and (e) promoting empowerment in Black women’s lives (P. H. Collins, 1991; Combahee River Collective, 1979).

Key assumptions of Black feminist theory include the following: (a) Black feminism assumes that race, gender, and class are constantly intersecting and, therefore, have a unique impact on the identity and view of Black girls and women; (b) the historical sexual exploitation of Black women, stemming from slavery, contributes to present-day racist and sexist stereotypes of Black girls and women due to the unique gender and racial specific experiences; (c) Black women cannot focus exclusively on their oppression as a woman or their oppression as being Black; (d) Black women’s U.S. social status provides distinctive experiences that offer a different view of reality than that available to other groups; (e) Black women possess a unique set of shared experiences, based on common perceptions of Black women as a group; and finally, (d) Black women can only be emancipated when all systems of oppression are eliminated (P. H. Collins, 1991; Combahee River Collective, 1979).

The historical, sociocultural, and racial context of the experiences of African American women has contributed greatly to the HIV/AIDS and STD epidemic. African American women have been historically sexually exploited in the United States for multiple generations since the 1600s (Andersen & Collins, 2014). Although African American men and women suffered greatly, enduring physical, mental, and emotional abuse during slavery, the treatment of enslaved women was unique and specific, due to their gender (Andersen & Collins, 2014). Negative stereotypes of African American women stem from the residual effects of slavery and contribute to oversexualized perceptions and expectations placed on African American girls and women. Black feminism (P. H. Collins, 2000; Davis, 1981; hooks, 1984; Lorde, 1984) emerged from the need to discuss interlocking identities of race, class, and gender and to validate the lived experiences of Black women that cannot fit into a single categorical axis (Crenshaw, 1989).

Ecological Systems Through a Black Feminist Lens

Whereas ecological systems can be viewed as an overarching macrotheory (Few, 2007), Black feminism, as a standpoint theory, offers a theoretical framework for why African American female adolescents are at increased risk of contracting HIV. Individuals learn to perceive the world and themselves from the perspective of their social group, including its history. Group characteristics such as race and gender shape group members’ knowledge and actions (P. H. Collins, 1991). Black feminism reflects complex interactions among historical, institutional, legal, and cultural factors whereas ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986) emphasizes how change or conflict in any one system ripples throughout other layers, thereby affecting human development.

In studying African American female adolescent development, a researcher must look not only at the child and her immediate environment but also at the interaction of systems in the larger cultural environment. Black feminism requires a critical analysis of these multiple layers as they relate to the individual, her family, and to the groups of which the individuals are a part (Few, 2007). Examination of the mesosystem and macrosystem may reveal not only historical institutional discrimination but also the evolution of identity development in African American female adolescents (e.g., standpoint). Thus, ecological theory provides support in acknowledging the historical context of the adolescent and the increase of HIV susceptibility in this group.

Applying Theory to a Family Intervention for African American Female Adolescents

HIV-risk-reduction interventions focus primarily on promoting safe sex and abstinence but do not consider social factors and external processes that contribute to sexual risk. Environmental context impacts low-income African American women’s likelihood of HIV infection (Gentry, Elifson, & Sterk, 2005). Black feminist theorists shaped a five-theme approach to analyze African American women’s experiences: (a) self-definition and self-valuation; (b) interconnecting race, class, and gender; (c) unique experiences in the United States; (d) controlling images constructed for African American girls and women; and (e) structure and agency as a platform for social change (P. H. Collins, 2000; hooks, 1984; Lorde, 1984). Psychological theories often rest on limited culturally relevant information, failing to acknowledge that low-income women risk contracting HIV in different ways that are often ignored in HIV risk interventions, assuming they are a homogeneous group (Gentry et al., 2005).

Gentry et al. (2005) offered ways to address external familial processes in HIV-risk-reduction interventions that contribute to risky behaviors such as lack of familial relationships and less stigmatizing interactions. Interventions can target specific group differences. Specific, modifiable techniques must address HIV risk reduction in low-income African American women through analysis of their unique experiences. Social needs are important in HIV- intervention research, relationship, and familial ties that are more important to participants than using HIV risk strategies. Black feminism allows HIV-risk-reduction programs to tailor strategies to gender, class, and race, specific to African American girls and women (Gentry et al., 2005).

M. L. Collins et al. (2015) examined the social realities of African American female adolescents and social influences that affect their sexual health. The study used Black feminist theory as a guide and Photovoice (Wang, 1999) as a methodology. The study of eight African American girls, aged 15 to 19 years, found that peers, environment, social media, and family connectedness shaped participants’ sexual behavior. Maternal connectedness and mother-daughter communication according to participants were most important in reducing sexual behavior in African American female adolescents. Photovoice provided participants with the ability to share their lived realities from their own perspectives, crucial concepts of Black feminist theory.

Researchers may ignore the interlocking systems of oppression that contribute to high-risk negative sexual behavior. Black feminism acknowledges the gap in research that ignores interlocking systems of oppression—racism, sexism, and classism—that contribute to high-risk sexual behavior that is specifically unique to African American female adolescents.

Mediating Variables in Safe Sexual Behavior in African American Female Adolescents

Although parent-child sexual-risk communication aligns with decreased sexually risky behaviors in adolescents, mediating factors such as self-efficacy in African American daughters contribute to the likelihood of engaging in safe sexual behaviors (Hutchinson et al., 2003; Kalichman et al., 2002; C. M. Mitchell, Kaufman, & Beals, 2005; Rostosky, Dekhtyar, Cupp, & Anderman, 2008). Self-efficacy, an individual’s belief in her ability to perform a particular behavior in a given situation, mediates the relationship between her knowledge and skills in performing a behavior and her actual performance of a behavior (Bandura, 1982). For example, condom-use self-efficacy aligns with less sexually risky behaviors in adolescent females who communicated with their mothers about sexual risk (Hutchinson et al., 2003). Self-efficacy to engage in safe sexual behaviors has been found in literature to be moderated by parental sexual-risk communication; thus, parents who communicate with their daughters increase their daughter’s self-efficacy to engage in safe sexual behaviors (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2016; Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998; Miller, Forehand, & Kotchick, 1999).

Paternal Influence on Adolescent-Female Sexual Behavior

Limited research examines HIV risk communication from fathers to their daughters in African American families. Brown, Rosnick, Webb-Bradley, and Kirner (2014) aimed to explore the relationship between paternal sexual communication, content, and safe sex practices among African American women. The study found that paternal communication of self-worth aligned with higher levels of condom usage among women in the study. Qualitative analyses gave insight to paternal processes that would be useful in developing family HIV-risk-intervention programs by encouraging researchers to focus on empowering African American girls and women rather than to primarily focus on the negative attributes of heterosexual relationships, sex, and its possible dangers. The study suggests that not only is parental communication critical in reducing HIV risk behaviors but the content of communication is even more important. Overall, improving the self-esteem of African American female adolescents in addition to improving the quality of parent-daughter relationships may have a profound impact on sexual health outcomes.

Intervention Development

Two family evidence–based interventions were used to incorporate measurable concepts that can be modified and adapted to parent-daughter interventions in African American communities.

Bronfenbrenner and Cochran (1976) developed Family Matters, a home-based parent-child intervention that trained neighborhood workers to increase parental involvement through the use of parent-child in-home activities. The goal of the intervention was to ultimately improve educational outcomes and foster healthy development in urban children. Home and community-based interventions allow researchers to examine the lived experiences of participants by being a part of their environment, discerning how multiple systems in their neighborhoods directly impact family processes and development. The intervention used a strengths-based approach as trained neighborhood workers were to assume that parents are the experts on how to effectively raise their own children. In-home activities were heterogeneous in nature across participating families in the study. Trained workers initially collected information from parents on their view of the development of their child and encouraged parents to provide input for in-home parent-child activities. Parents who completed the intervention were more likely to have a higher sense of empowerment, and children in the study performed better in school than children who did not receive the intervention.

Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2011) created the Families Talking Together intervention to empower African American and Latina mothers to talk to children about sexually risky behaviors by increasing knowledge of adolescent sexual health disparities, improving adolescent self-esteem, and providing effective sexual-risk strategies. The intervention was designed to be implemented by mothers through the use of educational materials provided by a social work interventionist. All mothers in the study received a booster call approximately 1 month after they enrolled in the intervention and then another booster call after 5 months of enrollment. The purpose of the booster calls was to identify whether participants reviewed intervention materials and to provide support to mothers. Intervention materials included cultural and gender-specific information pertaining to adolescent sexual education, and communication strategies on how to discuss sexual risk with their children. Results from the intervention indicated that adolescents in the study were less likely to have sex than adolescents in the control group who did not receive the intervention.

This model was inspired by both the parent-child community-based interventions with the intent to improve HIV risk communication between African American parents and daughters.

With theoretical guidance from both ecological systems theory and Black feminist theory, I propose a parent-child intervention be developed specifically for African American female adolescents and their families. Through an ecological lens, the community-based intervention would take place in the family home, implemented by sexual health educators who are licensed social workers. Community organizations and neighborhood schools are expected to be involved in the intervention only to encourage school faculty and organizations to disseminate information and encourage parent-child sexual-risk and HIV-risk communication. Derived from Family Matters (Bronfenbrenner & Cochran, 1976), one of the goals of their intervention involved social exchange beyond the immediate family, such as the exchange of informal resources at schools and emotional support from neighbors and other friends within their community. Thereby, strengthening mesosystem interactions in addition to alleviating parental stress by incorporating more supports and connection to valuable resources in their communities.

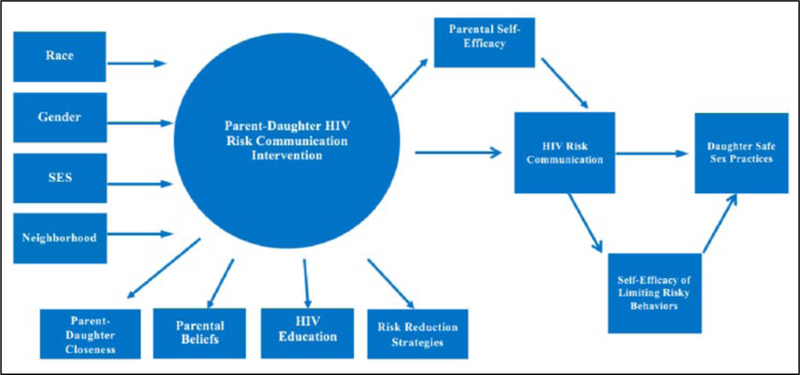

Intervention concepts derived from Black feminist theory involve discussing the history of Black women in the United States and how history influences HIV risk in African American female adolescents. Parents will learn how to discuss HIV risk with their daughters and how to become closer to their daughters by relaying messages of empowerment through communication (P. H. Collins, 1991; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

African American parent-daughter HIV risk communication intervention model. Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

Methodology for Proposed Intervention

Effective methodology in critical feminist theorizing is ideal in family science research to adapt an appropriate model: (a) centrality, normality, and value of women’s (and girls) experiences that are primarily gender specific; (b) using gender as a basic organizing concept, emphasizing gender-power relations; (c) insisting that gender relations be analyzed in sociocultural and historical contexts; (d) acknowledging the unique familial structure that challenges heterosexual normativity, class, and culture; and (e) emphasizing social justice and social change (Boss et al., 2004; Eichler, 1988). In using feminism in family science work, gender should not be limited to an individual or particular adolescent but expanded to include the familial network and macro sociocultural contexts. Researchers should use a variety of traditional (e.g., interviews, surveys, and ethnographies) and nontraditional (e.g., poetry, diaries, and Photovoice) data sources to examine the lives of Black women and their families (Bell-Scott, 1995).

An explanatory sequential design is ideal to examine the lived experiences of African American female adolescents and their parents. Quantitative analysis and then qualitative analysis will evaluate the effects of the theoretical model in HIV risk conversations, and semistructured interviews with parents, designed based on the results of quantitative analyses, will discern experiences in the intervention, challenges, and suggestions to improve future parent-daughter interventions. Questions to be included in semistructured interviews with parents follow: What suggestions do you have to make the intervention more accessible to parents and daughters? What did you most like about the intervention? What was the most uncomfortable part of the intervention? How did you initiate conversations with your daughter?

Quantitative analyses will determine if the parent-daughter intervention was effective in increasing HIV risk communication and if parent-daughter HIV-risk communication predicts reduction in sexually risky behaviors in African American daughters. Multivariate analysis will test the relationship between the effects of parent-daughter intervention and sexual behavior in daughters. Ideally, the study will be longitudinal, affording the opportunity to examine the effects of the intervention at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months, assessing if parent-daughter sexual-risk communication predicts a lower incidence of sexual risky behaviors over time.

Parents and daughters will receive pretest and posttest surveys with a follow-up survey after 3 months to examine if intervention effects are sustainable. Daughters in the study will also receive a posttest survey to assess (a) perceived parent-child sexual-risk communication, (b) sexually risky behaviors, and (c) self-efficacy to limit sexually risky behaviors. Qualitative analysis will be conducted for daughters in a semistructured format after examining quantitative results. An example of qualitative questions for daughters follows: What type of messages did your parents give you about HIV and sexual risk? What is your definition of risky sexual behavior? What does female empowerment mean to you? How do you view yourself?

Quantitative Measures for Parents

Self-Efficacy for Talking about Sex Scale (Dilorio et al., 2001).

Child-Parent Relationship Scale (CPRS; Pianta, 1992).

HIV Transmission Knowledge Scale (Carey & Schroder, 2002).

Parent-Child Sexual Risk Communication for Parents (Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998).

Quantitative Measures for Daughters

Brief HIV Knowledge Scale (Carey & Schroder, 2002).

Parent-Teen Sexual Risk Communication Scale (Hutchinson, 2007; Hutchinson & Cooney, 1998).

Safe Sex Behavior Questionnaire (Dilorio, Parsons, Lehr, Adame, & Carlone, 1992).

Self-Efficacy for Limiting Sexual Risk Behaviors (Smith, McGraw, Costa, & McKinlay, 1996). This scale should be modified to include questions regarding intravenous drug usage, which is a risk factor in HIV diagnoses.

Researchers will visit parents and children every 6 months to provide parents with new information on HIV prevention and ask parents to express their concerns and challenges, if any, regarding progress in their relationship with their daughters. Daughters will take part in focus groups to discuss challenges in communicating with their parents about sex and perceived barriers they may continue to face in their communities.

Implications

Viewing African American female adolescents through a Black feminist lens acknowledges their experiences and interlocking and contributing factors that limit their ability to reduce HIV risk. Through an ecological lens, Black feminism acknowledges the impact of multiple culturally relevant systems in their lives that contribute to peer, family, and community dynamics, affecting their development. Parents of African American female adolescents have a difficult role in protecting their daughters while challenging the often-subtle messages of sexually risky behaviors, due to the normalization of racism and sexism. Parent-child interventions focused on African American daughters must address the historical impact and shared cultural experience of African American families, altering their views of society and themselves and shaping their behaviors and communication patterns.

Understanding the impact of community factors and interlocking systems that affect healthy development in African American female adolescents is essential in an effective HIV risk intervention. Those implementing a community-based intervention when working with families must remain aware of barriers and influences that can affect the effectiveness of the intervention and understand factors moderating the phenomena in the community (Bronfenbrenner & Cochran, 1976). Parents may be unaware of structural barriers and normalized sexually exploited images that influence their daughter’s sexual identities and behaviors. Using Black feminist concepts in the proposed parent-daughter intervention, specifically when teaching parents about risk-reduction strategies and the history of African American girls and women, should increase parents’ self-efficacy in talking to their daughters about sexual risk and simultaneously increase daughters’ self-efficacy to engage in safe sexual behaviors. Through messages of empowerment and reflection on Black women’s historical oppression and influence, we hope to influence African American female adolescents to protect their health.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biography

Ijeoma Opara, MPH, MSW, LSW, is pursuing her doctoral degree in Family Science and Human Development at Montclair State University. She is also a youth and family therapist and is licensed in New Jersey and New York. Her research interests include examining sexual health disparities in African American girls, HIV and substance abuse prevention, and adolescent development.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Acker J (1973). Women and social stratification: A case of intellectual sexism. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 936–945. doi: 10.1086/225411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen ML, & Collins PH (2014). Conceptualizing race, class, and gender In Race, class, and gender: An anthology (pp. 443–448). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz T, Rennells RE, & Todd E (2006). Ecological influences of sexuality on early adolescent African American females. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 2, 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Scott P (1995). Life notes: Personal writings by contemporary Black women. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger JP, Celentano DS, Curriero FP, Adler NP, Millstein SP, & Ellen JM (2004). Does parental involvement predict new sexually transmitted diseases in female adolescents? Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 7, 666–670. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.7.666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, & Steinmetz SK (2004). Family theories and methods In Sourcebook of family theories and methods (pp. 3–30), New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Cochran N (1976). The comparative ecology of human development: A research proposal (Working paper). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Rosnick CB, Webb-Bradley T, & Kimer J (2014). Does daddy know best? Exploring the relationship between paternal sexual communication and safe sex practices among African-American women. Sex Education, 14, 241–256. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.868800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, & Schroder KEE (2002). Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire. AIDS Education and Prevention, 14, 172–182. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2423729/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum J, Hutchinson M, Duan L, & Jemmott L (2013). Maternal HIV serostatus, mother-daughter sexual risk communication and adolescent HIV risk beliefs and intentions. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 2540–2553. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0218-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013a). Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010 (HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Vol. 17, No. 4).Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats12/Surv2012.pdf

- Collins ML, Baiardi JM, Tate NH, & Rouen PA (2015). Exploration of social, environmental and familial influences on the sexual health practices of urban African American adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37, 1441–1457. doi: 10.1177/0193945914539794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1991). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Combahee River Collective. (1979). The Combahee river collective statement. New York, NY: Kitchen Table Women of Color; Retrieved from http://circuitous.org/scraps/combahee.html [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, Article 8. Retrieved from http://chica-gounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf [Google Scholar]

- Davis AY (1981). Women, race, & class. New York, NY: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Dudley W, Wang D, Wasserman J, Eichler M, Belcher L, & West-Edwards C (2001). Measurement of parenting self-efficacy and outcome expectancy related to discussions about sex. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 9, 135–149. Retrieved from https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/W_Dudley_Measurement_2001.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Parsons M, Lehr S, Adame D, & Carlone J (1992). Measurement of safe sex behavior in adolescents and young adults. Nursing Research, 41, 203–208. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199207000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus P, & Jaccard J (2000). Adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 268–278. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus P, Miller KS, Kotchick BA, & Forehand R (2004). Why parents matter!: The conceptual basis for a community-based HIV prevention program for the parents of African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 5–20. doi: 10.1023/B:JCFS.0000010487.46007.08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler M (1988). Nonsexist research methods: A practical guide. Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Few AL (2007). Integrating Black consciousness and critical race feminism into family studies research. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 452–473. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd LJ, & Brown Q (2013). Attitudes towards and sexual partnerships with drug dealers among young adult African American females in socially disorganized communities. Journal of Drug Issues, 2, 154–165. doi: 10.1177/0022042612467009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry Q, Elifson K, & Sterk C (2005). Aiming for more relevant HIV risk reduction: A Black feminist perspective for enhancing HIV intervention for low-income African American women. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17, 238–252. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.238.66531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Gonzalez B, McCoy W, & Aranda D (2011). A parent-based intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior in early adolescence: Building alliances between physicians, social workers, and parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 48, 159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Jaccard J, Goldberg V, Casillas E, & Bouris A (2006). The content and process of mother-adolescent communication about sex in Latino families. Social Work Research, 30, 169–181. doi: 10.1093/swr/30.3.169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Gonzalez B, & Bouris A (2008). A conceptual framework for the analysis of risk and problem behaviors: The case of adolescent sexual behavior. Social Work Research, 32, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Lee JJ, & Jaccard J (2016). Parent-adolescent communication about contraception and condom use. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 14–16. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman A, & Kellas JK (2015). High school adolescents’ perceptions of the parent-child sex talk: How communication, relational, and family factors relate to sexual health. Southern Communication Journal, 80, 388–403. doi: 10.1080/1041794X.2015.1081976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- hooks b. (1984). Feminist theory: From margin to center. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK (2007). The parent–teen sexual risk communication scale (PTSRC- III): Instrument development and psychometrics. Nursing Research, 56, 1–8. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, & Cooney TM (1998). Patterns of parent-teen sexual risk communication: Implications for intervention. Family Relations, 47, 185–194. doi: 10.2307/585923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Jemmott IB, Sweet Jemmott L, Braverman P, & Fong GT (2003). The role of mother–daughter sexual risk communication in reducing sexual risk behaviors among urban adolescent females: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 98–107. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00183-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, & Gordon VV (2000). Parent-teen communication about premarital sex: Factors associated with the extent of communication. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 187–208. doi: 10.1177/0743558400152001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JM, Seth P, DiClemente RJ, & Lin A (2015). Association of depressive symptoms and substance use with risky sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections among African American female adolescents seeking sexual health care. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 2137–2142. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Stein JA, Malow R, Averhart C, Devieux J, Jennings T, …Feaster DJ. (2002). Predicting protected sexual behaviour using the information-motivation behaviour skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychology, Health, & Medicine, 7, 327–338. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana A, & Cooksey EC (2012). Examining the effect of maternal sexual communication and adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval on adolescent risky sexual involvement. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51, 557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavee Y, & Dollahite DC (1991). The linkage between theory and research in family science. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 2, 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, & Brooks-Gunn J (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 309–337. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.126.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A (1984). Sister outsider. New York, NY: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Clark LF, & Moore JS (1997). Sexual initiation with older male partners and subsequent HIV risk behavior among female adolescents. Family Planning Perspectives, 29, 212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Forehand R, & Kotchick BA (1999). Adolescent sexual behavior in two ethnic minority samples: The role of family variables. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 86–98. doi: 10.2307/353885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Kaufman CE, & Beals J (2005). Resistive efficacy and multiple sexual partners among American Indian young adults: A parallel-process latent growth curve model. Applied Developmental Science, 9, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, & Herbeck DM (2012). HIV-positive mothers’ communication about safer sex and STD prevention with their children. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 136–157. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11412158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC (1992). Child-Parent Relationship Scale. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Raiford JL, Seth P, & DiClemente RJ (2013). What girls won’t do for love: Human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infections risk among young African-American women driven by a relationship imperative. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 566–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Stanton B, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Black MM, & Li X (1999). Parental influence on adolescent sexual behavior in high-poverty settings. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 153, 1055–1062. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.10.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal DA, Feldman SS, & Edwards D (1998). Mum’s the word: Mothers’ perspectives on communication about sexuality with adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 727–743. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Dekhtyar O, Cupp PK, & Anderman EM (2008). Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: A possible clue to promoting sexual health? Journal of Sex Research, 45, 277–286. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KW, McGraw SA, Costa LA, & McKinlay JB (1996). A self-efficacy scale for HIV risk behaviors: Development and evaluation. AIDS Education and Prevention, 8, 97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SA, Townsend TG, Glasgow YM, & Ojie MJ (2011). Gold diggers, video vixens, and jezebels: Stereotype images and substance use among urban African American girls. Journal of Women’s Health, 20, 1315–1324. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8, 185–192. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Simons RL, & Kao M (1994). The effects of divorced mothers’ dating behaviors and sexual attitudes on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of their adolescent children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 3, 615–626. doi: 10.2307/352872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E, Dalberth B, Koo H, & Gard J (2010). Parents’ perspectives on talking to pre-teenage children about sex. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42, 56–63. doi: 10.1363/4205610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]