Abstract

This qualitative study examines the role of communication among African American mothers living with HIV and their daughters in HIV prevention. Multiple themes emerged from our analysis of semistructured interviews with mothers (n = 15), and their adult daughters, (n = 15) such as perceptions of HIV risk communication, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. The findings of the study revealed differences in communication between mothers and daughters. Daughters felt they did not receive adequate and frequent HIV prevention advice from their mothers. Implications include strengthening communication content between mother-daughter dyads in HIV prevention programs that can aid in reducing HIV risk.

Keywords: African American women, communication, HIV/AIDS, mother-daughter, prevention, qualitative, sexual risk

Introduction

More than 7,000 women in the United States were diagnosed with HIV in 2015; of those women, 61% were African American/Black (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), 2017a; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), 2017b). Although African Americans account for only 12% of the United States population, they represent 45% of HIV diagnoses (CDC, 2017b). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) findings estimates that one in 48 African American women will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime (CDC, 2017c).

In 2015, the New Jersey Department of Health reported that New Jersey ranked sixth among states with new HIV diagnoses in the country (New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH), 2016). Racial and gender disparities in HIV/AIDS diagnoses are also present in New Jersey as African Americans and Hispanics comprise almost one third (32.7%) of the population of New Jersey but account for 76% of persons living with HIV/AIDS (NJDOH, 2016; New Jersey Department of Health and Human Services (NJDHHS, 2013). Among people living with HIV/AIDS in New Jersey, 56% are African American (NJDOH, 2016; NJDHHS, 2013). As of 2015, African American women accounted for 63% of HIV/AIDS cases among women in New Jersey (NJDOH, 2016). Newark, which is the largest city in New Jersey and located in Essex County, has the largest population of people living with HIV/AIDS in the state. Among women living with HIV/AIDS in Newark, 83% are African American/Black (NJDOH, 2016). African Americans/Blacks represent 50.2 % of the city’s population, making it the city with the highest number of African Americans/Blacks in New Jersey (United State Census Bureau, 2015). Newark also has a great income disparity with 29% of the population living in poverty compared to 10.4% of New Jersey population—almost three times greater than the state population of individuals living in poverty (United States Census Bureau, 2015). Individuals living in poverty are at increased risk of having poor mental health and physical health symptoms and are more likely to engage in risky behaviors due to community norms and lack of adequate resources to alleviate risks (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Environmental and structural factors contribute to an increase in gender disparities in health and can greatly influence the transmission of STDs and HIV among vulnerable women (Opara, 2018).

African American HIV positive mothers

African American mothers living with HIV/AIDS tend to represent a vulnerable group that often experience daily hardships that impact their ability to make positive choices due to structural barriers (Mahadevan et al., 2014). Some African American HIV positive mothers live in under resourced inner city neighborhoods and lack significant financial, familial, and emotional support (Blais et al., 2014; Brackis-Cott, Mellins, Dolezal, & Spiegel, 2007). Additionally, they are exposed to racism, classism, and sexism which can contribute to chronic stressful conditions for HIV positive mothers (Blais et al., 2014; Brackis-Cott, Mellins, Dolezal, & Spiegel, 2007)

In addition, African American mothers living with HIV are often living with comorbidities and co-occurring disorders such as substance abuse, diabetes and heart disease, thus affecting their quality of life and ability to actively care for their children (Mahadevan et al., 2014). Families affected by a chronic illness such as HIV/AIDS tend to have more communication difficulties, poor social support, and lower family cohesion (Blais et al., 2014; Brackis-Cott, Mellins, Dolezal, & Spiegel, 2007). In addition, children of HIV positive mothers are similarly exposed to the risk factors that placed their mother at risk, at younger ages (Cederbaum, Hutchinson, Duan, & Jemmott, 2013). Literature on HIV risk in adult children of HIV positive mothers is limited. Protective factors in reducing HIV risk in African American women have consistently reported the importance of parent-child communication and family connectedness (Cederbaum, 2012; Cederbaum et al., 2013; Collins, Baiardi, Tate, & Rouen, 2015; Edwards, Reis & Weber, 2013; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007; Kaplan, Hormes, Wallace, Rountree, & Theall, 2016; Murphy, Roberts, & Herbeck, 2012; O’Sullivan, Dolezal, Brackis-Cott, Traeger, & Mellins, 2005). Among African American women, the mother-daughter bond has been cited as the most important relationship and describe mothers as the key person in providing information to them about health, sexuality, and HIV prevention (Cederbaum, 2012; Collins et al., 2015).

Previous research on parent-child HIV/AIDS communication

Several studies have indicated that a majority of mothers living with HIV/AIDS are comfortable in discussing their status and providing advice on HIV/AIDS risk to their children (Edwards, Reis, & Weber, 2013; O’Sullivan et al., 2005). Having a parent that lives with HIV/AIDS has been shown in studies to motivate and facilitate the discussion of safe sex practices in their HIV negative children (Cederbaum, 2012; Edwards, Reis, & Weber, 2013; Edwards & Reis, 2014; O’Sullivan et al., 2005). Children of parents living with HIV/AIDS that maintain open communication regarding HIV risk have been shown to be engage in limited sexually risky behaviors leading into adulthood (Murphy, Roberts, & Herbeck, 2012).

African American daughters of HIV positive mothers are an important group to target for HIV prevention activities, given the fact that they are more likely to engage in higher rates of risky sexual behaviors and are exposed to more environmental stressors than their peers with HIV negative mothers. A majority of the research examining communication amongst HIV positive mothers and their children is focused on abstinence and the reduction of sexual risky behaviors of adolescent females due to maternal communication of HIV risk (Cederbaum et al., 2013; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007; Jaccard, Dittus, & Gordon, 1998; Kapungu et al., 2010; Sutton, Lasswell, Lanier, & Miller, 2014). Although literature has shown the importance of parent-child communication, strategies to improve communication in adult women who are HIV negative and their mothers who are HIV positive mothers is non-existent. African American women present 64% of all HIV/AIDS diagnoses among women (CDC, 2017c). The HIV rate for African American/Black women 16 times higher than white women and 5 times higher than Hispanic women (CDC, 2017c). Despite current HIV/AIDS prevention initiatives, the gender and racial disparity in HIV/AIDS diagnoses continues to widen.

The data explored in the current study speak to the urgency of addressing HIV risk among African American women with HIV positive mothers. The objective of this study is to examine the sexual and HIV risk communication characteristics of HIV positive mothers as it is conveyed to their adult daughters and how these communication patterns can be utilized in order to prevent sexually risky behaviors and reduce HIV risk.

Theoretical framework

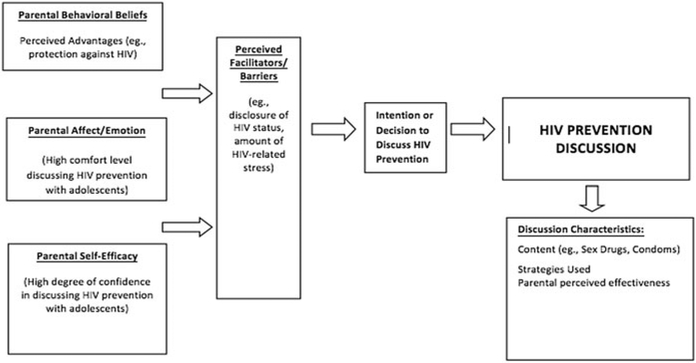

The Unified Theory of Behavior Change (UTB) (Bandura, 1977) and the Normative Model of Interpersonal Communication (NMIC) (Goldsmith, 2001) are both health behavior and communication theories that were utilized in guiding the results of the study. UTB has been shown to be an effective theory in predicting the frequency of parent-adolescent HIV risk communication (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Dittus, & Collins, 2008). UTB proposes three domains of parental communication, which will be used to conceptualize maternal communication characteristics: (a) parental behavioral beliefs, (b) parental affect/emotion, and (c) parental self-efficacy. Parental behavioral belief addresses the perceived advantages and disadvantages of parents communicating to their children about HIV/AIDS. Parental affect/emotion addresses the comfort level of the parent in discussing HIV and the emotional reaction when talking to child about HIV. Parental self-efficacy addresses the degree of confidence in talking about HIV with children (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2008).

The Normative Model of Interpersonal Communication (NMIC) (Goldsmith, 2001) focuses on describing, categorizing and explaining communication that has already occurred, including situational and contextual factors. Specific to parent-child communication, the NMIC is useful because it encourages researchers to provide a thoughtful analysis of conversations that have already taken place (e.g., contexts of HIV prevention conversations) (Edwards & Reis, 2014). NMIC was used to explain the strategies that parents used to discuss HIV prevention with their daughters. NMIC helped in understanding (a) the content of discussions, (b) the strategies parents use for discussing such topics, and (c) the perceived parental effectiveness of those strategies. Understanding how HIV positive mothers communicate with their daughters can increase maternal communication skills in future interventions.

Methods

Study design

The study utilized a qualitative approach in which structured interviews were used. Individual interviews with mothers living with HIV (n = 15), and female daughters (n = 15) elicited perceptions, beliefs and attitudes about HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviors. Prior to the start of the interviews, participants were asked to complete a brief demographic questionnaire. The purposive sample that met the study’s inclusion criteria were recruited from several community-based organizations and waiting rooms of HIV/AIDS clinics in the greater Newark, New Jersey area. Interviews were held in private areas of the community based organization that participants were recruited from, as well as in private library rooms for organizations that did not have private interview space available.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for mothers included (a) 18 years and older, (b) self-identify as an African American, and (c) diagnosed with HIV. The criteria for daughters included (a) being HIV negative, (b) at least 18 years of age, (c) self-identify as African American, and (d) have a mother living with HIV and participating in the study. Mothers and daughters were interviewed based on their availability and willingness to participate in the study. Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were assured as there were no identifying information reported in the aggregate.

Semistructured interview guides were utilized with open-ended questions and probes for both the mothers and their daughters, and the mothers and daughters were interviewed separately. All of the interviews were audio-recorded and lasted approximately 1 hour. All audio-taped recordings were subsequently transcribed verbatim and analyzed for emergent themes. Signed informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Study participants received $30 for participating in the study. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was received and written consent was obtained from participants prior to study enrollment.

Interview guide

Three African American female research assistants conducted face-to-face interviews using a semistructured interview guide. The interview guide focused on open-ended questions related to knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding HIV/AIDS, HIV risk communication and social support. Questions were guided by Unified Theory of Behavior Change (UBC) and the Normative Interpersonal Communication Theory (NMIC) (Figure 1). Examples of some of the questions that were asked to the participants were “What does being healthy mean to you?” “What motivates you to take care of your health?” and “What do you talk with you daughters about, when it comes to HIV and HIV prevention?”

Figure 1.

Integrated model of mother/daughter communication about HIV prevention for mothers living with HIV/AIDS (Edwards et al., 2013).

Data analysis

Research assistants read through the data several times while creating labels and codes for the data that summarized the experiences of the participants. A priori template of codes were generated based on the research questions and anticipated themes (Crabtree & Miller, 1999) as well as inductively through open, axial and selective coding (Boyatzis, 1998). Analysis of interview data used an inductive approach through the identification of recurring themes and patterns in transcripts and memos (Boyatzis, 1998). This combined deductive and inductive approach complemented the research questions by allowing the tenets of the selected theories to be integral to the process of deductive analysis while allowing for themes to emerge directly from the data using inductive coding (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Two research assistants were designed as coders. The first rater reread the transcripts and selectively coded any data that were related to the core codes identified previously. A second rater performed the same steps outlined above for consistency to be achieved between both coders. Next, relationships and connections among the open codes were identified. Strategies of trustworthiness were implemented to enhance validity and reliability of the results. Members of the research team had prolonged engagement within the community in order to gain a better understanding of the organization in which participants were recruited from and establish trust (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Research team engaged in peer debriefing led by the first author reviewed interview protocols, transcripts, and analysis throughout research process (Shenton, 2004). Finally, transcripts were coded by two different coders and 90% inter-related reliability was achieved. After initial coding of the data, the authors summarized and organized the results in ATLAS.ti 7 software.

Results

This study examined how mothers living with HIV/AIDS described their communication and interactions with their adult daughters, particularly regarding conversations about protecting themselves from HIV and their perceptions of HIV transmission and risk. The results of this study were guided by the frameworks of the Normative Model of Interpersonal Communication (Goldsmith, 2001) and Unified Theory of Behavior Change (Bandura, 1977).

All of mothers in the study self-identified as African American. Mothers’ ages ranged from 35 years to 66 years old with a mean age of 50 years. Additional information regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the mothers can be found in Table 1. Regarding the mother’s reported sexual behaviors, the vast majority of mothers were 15 years old or younger at their first sexual intercourse. Approximately one quarter of participants had ever exchanged money or gifts for sex and fourteen mothers reported a history of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) (Chlamydia was the most common STI reported). Most of the mothers had been living with HIV for 10 or more years. Thirteen mothers reported an existing comorbidity while more than half had more than one comorbid condition. Some of these comorbidities included: hypertension, diabetes, depression and cancer. Additional information regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the mothers can be found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic of mothers (N=15).

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Black | 15 |

| Age (Range) | 35–66 |

| Mean (SD) | 49.9 |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school or less (no GED) | 8 (53) |

| High school Diploma | 6 (40) |

| College graduate or professional degree | 1 (6) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 6 (40) |

| Long-term relationship | 4 (26) |

| Other (single, divorced, separated, widowed) | 5 (33) |

| Annual income | |

| 0–$24,999 | 10 (67) |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 3 (20) |

| $35,000–$44,999 | 1 (7) |

| ≥$45,000 | 1 (7) |

Percentage may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Table 2.

Sexual risk behavior characteristics of mothers.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at first sexual intercourse (oral, vaginal, or anal) | |

| 11 years or younger | 5 (33) |

| 12 years | 3 (20) |

| 13 years | 1 (7) |

| 14 years | 4 (27) |

| 15 years or older | 2 (13) |

| Number of sexual partners in past 3 months | |

| 1 | 13 (86) |

| 2 | 2 (13) |

| Ever had sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol | |

| Yes | 10 (66) |

| No | 5 (33) |

| No | 1 (6) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis | |

| 0–6 months | 1 (7) |

| 4–6 years | 3 (20) |

| 7–9 years | 9 (60) |

| ≥10 years | 3 (20) |

Percentage may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

The sociodemographics characteristics for the daughters (n = 15) in the study are as follows: ages ranged from 18 years to 42 years of age with a mean age of 29.2. Thirteen of the daughters reported ever having had sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Nearly one-fourth reported not using condoms or dental dams at last sexual intercourse. Nearly all of the daughters (14) indicated having their first sexual intercourse before the age of 18, while one daughter reported not remembering her age during her first sexual intercourse. Additional information regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the mothers can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected sociodemographics and sexual risk behavior characteristics of the daughters (N=15).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (range) | 16–42 |

| Mean (SD) | 29.2 (7.8) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school or less (no GED or diploma) | 5 (33) |

| High school graduate/GED | 7 (46) |

| Some college/technical/vocational | 2 (13) |

| College graduate or professional degree | 1 (6) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 2 (13) |

| Single | 3 (20) |

| In a relationship | 9 (60) |

| Other (divorced, separated, widowed) | 1 (6) |

| Annual income | |

| 0–$24,999 | 12 (80) |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 1 (6) |

| $35,000–$44,999 | 1 (6) |

| ≥$45,000 | 1 (6) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 9 (60) |

| Employed (full-time) | 4 (27) |

| Employed (part-time) | 1 (6) |

| Other (social security, disability) | 1 (6) |

| Ever had sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol | |

| Yes | 13 (86) |

| No | 2 (13) |

| Ever been diagnosed with an STI | |

| Yes | 5 (26) |

| Age of sexual intercourse | |

| Before the age of 18 | 14 (93) |

| Used a Condom or Dental Dam at last sex | |

| Yes | 10 (67) |

| No | 5 (33) |

Percentage may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Parental behavioral beliefs

All of the mothers in the study (n = 15) expressed an understanding of the advantages of communicating with their daughters about HIV. The mothers believed that talking to their daughters about their sexual histories as well as ways to practice safer sex were very important.

All boys want do is just do this, and then they want to be done with you! I don’t want her to be on the path I was on.

Mothers in the sample also felt a great importance to discuss their own perceived mistakes and share personal stories to reduce risky behaviors in their daughters:

You know I was an IV drug user and that’s how I got it. I tell my daughter to stay away from bad company, you know? That’s how I ended up using.

Mothers believed that it was their responsibility to discuss HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases to their daughters:

I let her know that this disease is out there. I let her know that HIV is out there, Hepatitis C is out there … hepatitis, tuberculosis, it’s a lot of diseases out there that people don’t talk about, because they try to keep it sealed or undercover so it’s up to me to let her know about it because I got it and no one told me about it.

Most of the mothers felt that through their lived experience of being HIV positive, they were more than qualified to talk to their daughters about contracting HIV:

I tell her you never know who has it. HIV doesn’t have a look, today. So, you really need to protect yourself by all means necessary. Go get tested. You know? That’s one of the things I think they should mandate testing like they do pap smears and stuff … I think I had of been tested in the first, maybe I wouldn’t have been as long down the line before. I remember when ex-husband was in the hospital at the VA and the nurse said ‘I can’t tell you what’s wrong with him, He has to tell you,’ that should’ve been a trigger for me.

Thus, for mothers in the sample the need to take responsibility in providing information to their daughters about the dangers of unprotected sex and injection drug use were made clear through the quotes from the mothers.

Parental affect/emotion

Overall, mothers reported a range of responses when asked about their communication level and frequency of communication about HIV prevention with daughters. The majority of mothers reported that it was relatively easy to talk to their daughters about ways to protect themselves from HIV and other STIs. In addition, the mothers reported talking to their daughters frequently about HIV prevention. Interestingly, when examining the data from the daughters, approximately 40% of daughters reported not receiving any information about HIV prevention from their mothers. The majority of daughters reported not communicating with their mothers about HIV prevention or sex. This presents a missed opportunity for effective communication between the daughter and her mother regarding sexual risk behavior and the implications of risky behavior for HIV.

Mothers believed that they communicated with their daughters frequently and that sexual risk communication involves discussing safe sexual behavior and the dangers of contracting HIV:

Safe sex, just being aware of the people, don’t judge them books by its cover. Things like that. Probably like, I don’t know; whenever it comes up, once a week or something, twice a week.

One mother expressed comfort in discussing safe sexual behaviors and felt the need to encourage her daughter to place her future goals as priority:

I tell them, make sure you protect yourself. Make sure you take a person to the doctor, get them checked out for an HIV test. And don’t have sex until you turn 19. And don’t worry about these boys out here, because they ain’t no good for you. And that’s about it. And stay in the books, go to school, go to college …

One mother perceived that her daughter may be uncomfortable talking to her about HIV and sex although she encourages her daughter to be open and honest:

She never said … We never said anything about it. I just know she felt uncomfortable about saying whatever, you know; and I just reassure her that ‘It really doesn’t, it doesn’t bother me about, you know, the situation or what you’re going through.’ If anything … If she feel comfortable coming to me, I don’t mind answering anything or helping out with anything.

Another mother admitted that she does not talk to her daughter about sexual risk due to being uncomfortable:

We don’t really talk about it. We talk about doctor visits some days and we only talk every six months for updates.

The findings of the study highlight the range of emotions and discomfort that HIV mothers feel when talking to their daughters about their HIV prevention and sexually risky behaviors.

Parental self-efficacy

The majority of mothers reported having confidence to talk about HIV with their daughters. Mothers attributed this confidence to the good relationships they have with their daughters. In addition, daughters reported trusting the information they received from their mothers regarding HIV information. However, mothers reported being skeptical and felt their daughters were not being truthful in communicating with them about their sexual history and lifestyle.

Mother-daughter closeness was a mediating factor in the majority of mothers in the sample that reported discussing HIV risk and prevention with their daughters:

I can talk to her about anything because we are close when she don’t push me away. But that’s a typical teenager. Like, who wants their mom always around them? And I know I can be like a pest sometimes; but sometimes, I think my pessimism can be a support. I’m a good listener to that. Also I trust it to a certain extent, because I think my daughter will tell me what she thinks I want to hear; and she don’t tell me the whole truth.

I think we have a very close relationship where if something would have happened, I think she would come. Because I’ve been speaking to her from day one and I can trust everything she tells me as far as her sex life is concerned.

We talk about everything really … I go to her and talk to her about my issues with the meds and stuff … I trust what she tells me because I don’t see why she will lie, she is grown now with her own child.

One mother reported that trust was a key factor in her and her daughters’ ability to talk about HIV and sex. She felt that her daughter was not comfortable talk to her about sex however, the mother believes that her daughter would talk to her if she was curious about sex:

I talk to her about HIV and sex. The kinds of things we talk about on sex are, ‘are you having sex?’ I don’t care about nothing else! Like, ‘Are you having sex?’ You know? And her answer’s always, ‘No,’ or ‘You’re so aggie; I don’t want to talk about that. Why you keep talking about that?’ It doesn’t go any further than me saying, I trust her to a degree. Like, if I had to put it on a percentage level: 60%.

In this sample of mothers, parental self-efficacy was very high, and denotes a strong level of confidence in mothers’ ability to speak to their daughters about HIV.

Perceived facilitators and barriers

Overall, all of the mothers in the study reported that it was relatively easy to talk to their daughters about HIV, sex, and ways to protect themselves from HIV and other STIs. For example, one mother stated that “talking about sex and HIV makes her (daughter) uncomfortable but not me because my goal is to protect her and to not allow her to go down the same path I took”. Some of these mothers reported that conversations about HIV and sex were not hard for them personally, but they acknowledged that topics like sex and drugs could be uncomfortable for daughters and some mothers to bring up.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship and communication characteristics between HIV positive mothers and their adult daughters around HIV prevention. Our results, guided by the frameworks of Normative Model Interpersonal Communication (Goldsmith, 2001) and Unified Theory of Behavior Change (Bandura, 1977) included mothers and daughters’ response to open- ended interview questions in order to understand the barriers in communication skills based upon the perceptions, beliefs and attitudes about HIV risk behaviors. The qualitative findings provide the foundation for future interventions that address the prevention of new HIV infections as well as providing opportunities to reduce potential communication barriers between HIV positive mothers and their daughters. Findings are consistent with previous research indicating that African American females that have a mother living with HIV are at high risk of engaging in risky behaviors leading to exposure to HIV (Barman-Adhikari, Cederbaum, Sathoff, & Toro, 2014; Cederbaum, Guerrero, Barman-Adhikari, & Vincent, 2015; Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006). Using drugs and alcohol has been shown to increase the risk of engaging in unsafe sex practices such as having sex without a condom or even being vulnerable to sexual assault and/or rape in the case of female adolescents (Jackson, Seth, DiClemente, & Lin, 2015; Le, Behnken, Markham, & Temple, 2011).

In the interviews, mothers reported talking to their daughters frequently about HIV prevention, but the results indicate that some of the daughters reported that they did not receive any information about HIV prevention from their mothers. This discrepancy in HIV prevention communication highlights the complexity of sexual risk conversations between mother and daughter. The discrepancy between reports has also been seen in previous studies that examine HIV and sexual risk communication between mothers and daughters (Jaccard, Dittus, & Gordon, 1998; O’Sullivan et al., 2005). This discrepancy can be due to multiple factors that pertain to the daughter’s perceptions of sexual risk discussions, communication barriers, and potentially the differences in the ages of daughters or their sexual histories. This discordance represents a missed opportunity for HIV prevention utilizing the relationship that African American HIV positive mothers have with their daughters.

Due to the unique vulnerabilities of African American mothers living with HIV, understanding how to effectively communicate proper safe sex practices strategies can be difficult due to a number of factors such as mother-daughter closeness and comfort level. Cederbaum et al. (2013) discusses the strength of mother-daughter relationships and how that can have a direct impact on reducing sexually risky behaviors in daughters and the ability to have safe sex discussions. HIV/AIDS stigma may also contribute a key role in the discussion of HIV prevention strategies as mothers may not feel comfortable discussing their status in depth, and thus be potentially hesitant or unwilling to further provide safe sex and HIV prevention advice.

Frequency of HIV risk communication has been shown to be based on parent’s comfort in disclosing HIV status with their children (Le, Behnken, Markham, & Temple, 2011). Edwards et al. found that 80% of the parents in their study whom were HIV positive, contributed their HIV status as a motivator to discussing safe sex practices and HIV prevention (Edwards, Reis, & Weber, 2013). The qualitiative results of the study found that parents living with HIV, felt confident that their lived experience of being HIV positive, provided them with the unique ability to speak to their children about HIV risk. Only 8% of the parents in their sample felt being HIV positive was a barrier, as they did not feel they could accurately explain what HIV was to their children and ultimately felt their children would react in a negative way (Edwards, Reis, & Weber, 2013). Understanding the importance of perception is a key implication in developing strategies to improve HIV prevention and risk communication among HIV positive mothers and their daughters. Mothers perceptions of their daughters not being comfortable discussing drugs, substance abuse and HIV risk can be a significant barrier to HIV prevention.

Although mothers in the present study reported that they frequently discussed HIV prevention practices with their daughters, the perceptions of those discussions by their daughters is a potential hindrance to their ability to internalize their mother’s message regarding reducing sexual risk. Due to differences in perception of the comfort level in communication between mothers living with HIV and their daughters, additional attention and resources should be dedicated to programs that facilitate conversations regarding HIV prevention through enhancing effective dialog between mothers and daughters.

Conclusion

African American daughters of HIV positive mothers are at an increased risk of HIV due to the structural, historical barriers and environmental influences that have contributed to their potential engagement in risky sexual behaviors. Future research should address (a) frequency of sexual risk communication, (b) temporal factors such as the age of the daughter’s sexual debut, and (c) content of HIV specific discussions. Also of importance for consideration are how the age and literacy level of the daughters can have an impact on how HIV prevention messages are perceived. These factors should be considered in informing interventions designed to improve parental communication with daughters by providing clear and concise information regarding HIV prevention education.

The theories that were used to analyze the qualitative data analyzed from the interviews suggest several ways to interpret the information that may yield insight as to how essential and effective mother-daughter communication can be in the prevention of HIV among African Americans.

The findings reveal that more than half of the daughters used protection during their last sexual experience; with more programs to help implement effective communication, that statistic could increase tremendously. Additionally, increased mother-daughter sexual risk conversations could allow open dialog of experiences and reduce the risk of contracting HIV while increasing safe sex practices. The findings from this study have the potential to guide family scientists, social workers, and health educators that are working toward implementing programs in areas that have been previously demonstrated to be barriers in effective communication (such as depression and HIV related stigma) to assist with the overall goal of HIV/AIDS prevention in African American women.

It is important to note that African American mothers are extremely beneficial in discussing sexual risk prevention and education with their daughters. Research should utilize the mother-daughter relationship in sexual risk interventions that involves African American women, regardless of maternal HIV status, as the mother-daughter relationship is unique and valuable. Although evaluating the quality of the mother-daughter relationship can be complex; interventions should also incorporate the use of techniques aimed at strengthening the mother-daughter relationship, in order to establish rapport and build deeper trust and engagement. Mothers that are HIV positive have the unique advantage of using their lived experience as an example to educate and promote prevention message to their daughters who are HIV negative. Although this can be difficult, as multiple barriers can affect a mother’s ability to effectively discuss safe sex prevention strategies by disclosing their status, it is crucial to better facilitate the discussion of sexual health in order to reduce HIV incidence in the African American community.

Limitations

Although this study addresses the importance of communication between mothers living with HIV and their daughters it does not discuss the socioeconomic barriers as related to lower levels of education and low income as seen in both the mothers and the daughters in the study. Future studies should examine the additional layer of socioeconomic status of mothers living with HIV and their daughters in order to facilitate health education programs and interventions that will be successful in these populations. Additionally, as the data was collected from HIV positive African American women and their daughters, it is not generalizable to all mother- daughter relationships or women that are not from an urban community. Furthermore, the data was collected cross-sectionally, and did not allow for further examination regarding the timing of the conversations that the mothers had with the daughters.

The study was limited by the size and duration of the interviews due to the sensitivity of the topics being discussed. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews for the purposes of creating the opportunity to generate rich data and provide contextual aspects in order to understand participant’s perception. It is important to recognize and address other weaknesses this method of conducting semi-structured interviews such “the interviewer effect.” Interviewees may respond differently depending on how they perceive the interviewer which is defined as the interviewer effect (Denscombe, 1998). This problem could have been present in our study although we encouraged participants to be as open and honest as possible.

Self-reporting can produce over exaggerated or underreported information. However, it was important to allow participants to disclose the information that they felt relevant and state how they perceived certain experiences. This allowed the researchers to witness the important role of perceived information among participants and how perception can aid in understanding the dynamic in sexual risk communication between mothers and daughters.

Despite these limitations, we found the interviews to be appropriate for the exploratory nature of our study. With regard to sexual health communication research and HIV prevention, qualitative data is useful in providing context to a complex phenomenon and providing the ability to explore mothers and daughters lived experiences.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health Grant# 2R25MH087217–06

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman-Adhikari A, Cederbaum J, Sathoff C, & Toro R (2014). Direct and indirect effects of maternal and peer influences on sexual intention among Urban African American and Hispanic females. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31 (6), 559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais M, Fernet M, Proulx-Boucher K, Lapointe N, Samson J, Otis J, … Lebouché B (2014). Family quality of life in families affected by HIV: the perspective of HIV-positive mothers. AIDS Care, 26 (suppl1), S21–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis R (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brackis-Cott E, Mellins C, Dolezal C, & Spiegel D (2007). The mental health risk of mothers and children: The role of maternal HIV infection. Journal of Early Adolescence, 27 (1), 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum J (2012). The experience of sexual risk communication in African American families living with HIV. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27 (5), 555–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum J, Hutchinson M, Duan L, & Jemmott L (2013). Maternal HIV serostatus, mother-daughter sexual risk communication and adolescent HIV risk beliefs and intentions. AIDS and Behavior, 17 (7), 2540–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederbaum J, Guerrero E, Barman-Adhikari A, & Vincent C (2015). Maternal HIV, substance use role modeling, and adolescent girls’ alcohol use. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care: Janac, 26 (3), 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017a). HIV among African Americans. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017b). HIV among African Americans. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-hiv-aa-508.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017c). HIV among women. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/.

- Collins M, Baiardi J, Tate N, & Rouen P (2015). Exploration of social, environmental, and familial influences on the sexual health practices of urban African American adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37 (11), 1441–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree B, & Miller W (1999). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks In Crabtree B & Miller W (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 163–177.) Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Denscombe M (1998). The good research guide: for small-scale social research projects. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, Reis J, & Weber K (2013). Facilitators and barriers to discussing HIV prevention with adolescents: Perspectives of HIV-Infected parents. American Journal of Public Health, 103 (8), 1468–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, & Reis J (2014). A five step process for interactive parent-adolescent communication about HIV prevention: Advice from parents living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services, 13 (1), 59–78. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2013.775686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, & Muir-Cochrane E (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5 (1), 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith D (2001). A normative approach to the study of uncertainty and communication. Journal of Communication, 51 (3), 514–533. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, & Collins S (2008). Parent-adolescent communication about sexual intercourse: An analysis of maternal reluctance to communicate. Health Psychology, 27 (6), 760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich C, Brookmeyer K, Shrier L, & Shahar G (2006). Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological-transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31 (3), 286–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson M, & Montgomery A (2007). Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 29 (6), 691–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus P, & Gordon V (1998). Parent-adolescent congruency in reports of adolescent sexual behavior and in communications about sexual behavior. Child Development, 69 (1), 247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JM, Seth P, DiClemente RJ, & Lin A (2015). Association of depressive symptoms and substance use with risky sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections among African American female adolescents seeking sexual health care. American Journal of Public Health, 105 (10), 2137–2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan K, Hormes J, Wallace M, Rountree M, & Theall K (2016). Racial discrimination and HIV-related risk behaviors in Southeast Louisiana. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40 (1), 132–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapungu CT, Baptiste GA, Holmbeck C, Mcbride M, Robinson-Brown A, Sturdivant L, … Paikoff R (2010). “Beyond the ‘Birds and the Bees’: Gender differences in sex- related communication among urban African-American Adolescents.” Family Process, 49 (2), 251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Y, Behnken M, Markham C, & Temple J (2011). Adolescent health brief: Alcohol use as a potential mediator of forced sexual intercourse and suicidality among African American, Caucasian, and Hispanic high school girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49 (4), 437–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hill, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan M, Amutah N, Ramos L, Raines E, King J, & Leverett C (2014). Project THANKS: A socio-ecological framework for an intervention involving HIV positive African American women with comorbidities. Journal of Health Disparities Research & Practice, 7, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Roberts K, & Herbeck D (2012). HIV-positive mothers’ communication about safer sex and STD prevention with their children. Journal of Family Issues, 33 (2), 136–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH). (2016). HIV/AIDS Cases by Statewide Population Groups. Retrieved from: http://www.state.nj.us/health/hivstdtb/hiv-aids/popu-lationgroups.shtml

- New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (NJDHHS). (2013). New Jersey Part B Comprehensive Plan. Retrieved from: http://hiv.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Part-B-Comp-Plan_FINAL-2013.pdf.

- Opara I (2018). Examining African American parent-daughter HIV Risk communication using a Black feminist-ecological lens: Implications for intervention. Journal of Black Studies, 49 (2), 134–151. doi: 0021934717741900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan L, Dolezal C, Brackis-Cott E, Traeger L, & Mellins C (2005). Communication about HIV and risk behaviors among mothers living with HIV and their early adolescent children. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25 (2), 148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton AK (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MY, Lasswell SM, Lanier Y, & Miller KS (2014). Impact of parent-child communication interventions on sex behaviors and cognitive outcomes for black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino youth: A systematic review, 1988–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54 (4), 369–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United State Census Bureau. (2015). State & county Black population in the United States. http://census.gov.