Abstract

Context:

Providers can help clients achieve their personal reproductive goals by providing high-quality, client-centered contraceptive counseling. Given the individualized nature of contraceptive decision making, provider attention to clients’ preferences for counseling interactions can enhance client centeredness. The objective of this systematic review was to summarize the evidence on what preferences clients have for the contraceptive counseling they receive.

Evidence acquisition:

This systematic review is part of an update to a prior review series to inform contraceptive counseling in clinical settings. Sixteen electronic bibliographic databases were searched for studies related to client preferences for contraceptive counseling published in the U.S. or similar settings from March 2011 through November 2016. Because studies on client preferences were not included in the prior review series, a limited search was conducted for earlier research published from October 1992 through February 2011.

Evidence synthesis:

In total, 26 articles met inclusion criteria, including 17 from the search of literature published March 2011 or later and nine from the search of literature from October 1992 through February 2011. Nineteen articles included results about client preferences for information received during counseling, 13 articles included results about preferences for the decision-making process, 13 articles included results about preferences for the relationship between providers and clients, and 11 articles included results about preferences for the context in which contraceptive counseling is delivered.

Conclusions:

Evidence from the mostly small, qualitative studies included in this review describes preferences for the contraceptive counseling interaction. Provider attention to these preferences may improve the quality of family planning care; future research is needed to explore interventions designed to meet preferences.

Theme information:

This article is part of a theme issue entitled Updating the Systematic Reviews Used to Develop the U.S. Recommendations for Providing Quality Family Planning Services, which is sponsored by the Office of Population Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

CONTEXT

Contraceptive counseling is a common healthcare experience in the U.S.1 The National Survey of Family Growth, a nationally representative survey of women of reproductive age, has found that more than 50% of sexually active women report receiving a family planning service related to birth control in the past 12 months.1 Contraceptive counseling delivered during this care presents a key opportunity for healthcare providers to help clients achieve their personal reproductive goals, as well as contribute to clients, improved relationships with providers and the healthcare system. Quality contraceptive counseling has been found to be associated with contraceptive continuation2 and to help build trust between clients and providers.3 In addition, provision of quality, client-centered counseling that focuses on client experiences, values, and preferences is an ethical goal in and of itself.4

Providing Quality Family Planning Services (QFP), published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population Affairs in 2014, identifies client centeredness as a core aspect of quality care.5 The QFP defines client-centered care as “care [that] is respectful of, and responsive to, individual client preferences, needs, and values; client values guide all clinical decisions.” The National Academy of Medicine’s recognition of the importance of patient centeredness throughout health care6 informed the QFP’s emphasis on client centeredness. Client-centered care is particularly important in contraceptive counseling because of the personal nature of reproductive decisions and the complex individual, social, and cultural factors that may influence contraceptive method selection and use.

Research suggests a need for improvement in the provision of client-centered contraceptive counseling. Women have reported dissatisfaction with contraceptive counseling in general, and specifically with the information and decision support they receive.3,7–9 Understanding client preferences for contraceptive counseling and tailoring the interaction accordingly is essential to providing client-centered care. Efforts in this area are especially important considering challenges that may hinder the delivery of client-centered care, such as time constraints and competing medical priorities during visits.10

To inform recommendations included in the QFP, CDC and Office of Population Affairs conducted a series of systematic reviews on contraceptive counseling and education during 2010–2011. Efforts to update this series began in 2015. Building on the value QFP places on client-centered family planning care, the updated series includes explicit attention to client preferences for contraceptive counseling. The objective of this report is to summarize the evidence on these client preferences.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

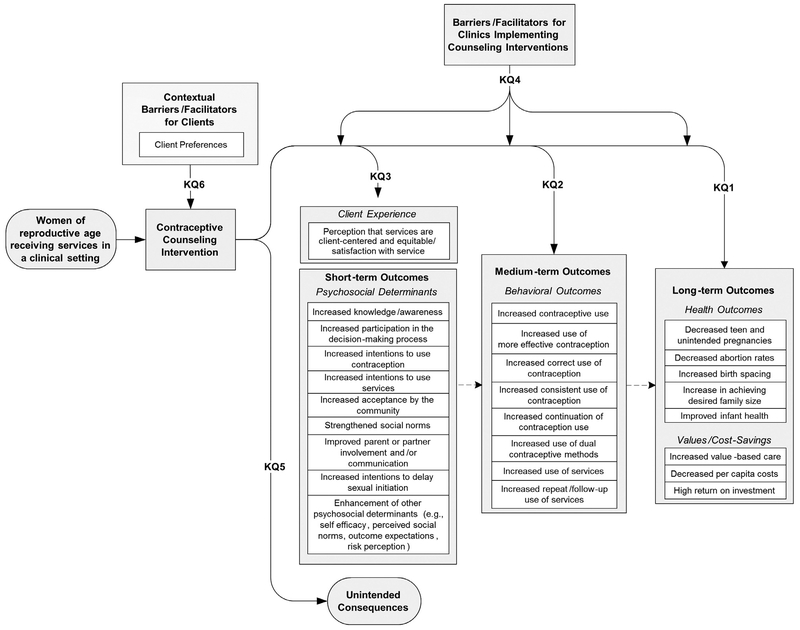

The methodology for conducting this systematic review was similar to the approach used in the reviews in the prior series and has been described elsewhere.11 Briefly, six key questions (KQs) were developed (Appendix Table 1, available online) and an analytic framework applied to show the relationships between the population, intervention, and outcomes of interest (Figure 1). KQs 1–5 were included in the prior review on contraceptive counseling12 and are addressed elsewhere in this issue. KQ 6, which asks, “What are clients’ preferences with regard to contraceptive counseling approaches in the family planning setting?” was added during this review update process, in keeping with QFP’s emphasis on the importance of client-centered care. Although KQs 1–5 address the outcomes and implementation of counseling interventions, KQ 6 is a unique addition in its explicit focus on describing client preferences. This review describes the evidence for KQ 6.

Figure 1.

Analytic framework for systematic review on contraceptive counseling and education.

KQ, key question.

For the review series, 16 electronic bibliographic databases were searched for studies related to KQs 1–6 published from March 2011 through November 2016. Because KQ 6 was not included in the prior review, a limited search was conducted of ten electronic bibliographic databases for earlier research published from October 1992 through February 2011 (six of the 16 databases used for the latter time period were unavailable because of institutional barriers). October 1992 was selected as the beginning date because that is when the Food and Drug Administration approved injectable contraception for use, marking a shift in the range of available contraceptive options, and thus a potential change in counseling preferences. Although fewer databases were used for the limited search, the conclusion was drawn that these databases were sufficient, given that the six excluded databases had not yielded any relevant articles in the search of literature in the latter time period.

Search terms were developed for the updated review series (Appendix Table 2, available online), which were used to identify potential articles related to KQs 1–6 from March 2011 through November 2016; the search terms were revised to be specific to KQ 6 in the search of literature published prior to 2011.

Selection of Studies

Inclusion parameters defined a priori required that studies be (1) conducted in the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or European countries categorized as “very high” on the Human Development Index13; (2) written in English; and (3) available as full-text articles (e.g., not abstracts from conference presentations). Specific to this review, additionally, studies must have examined client preferences among women of reproductive age (15–45 years) and must have been related to client preferences for contraceptive counseling delivered in a clinical setting. All study designs were included.

Two authors reviewed titles and abstracts of identified articles. Inter-reviewer agreement on exclusion decisions was assessed using κ statistics, ensuring a statistic of 0.8 or higher. Full-text articles were retrieved if they did not meet exclusion criteria at the title and abstract review stage. Study characteristics and findings from articles meeting the inclusion criteria for this review were abstracted. The quality of each piece of evidence was assessed using the grading system developed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.14

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

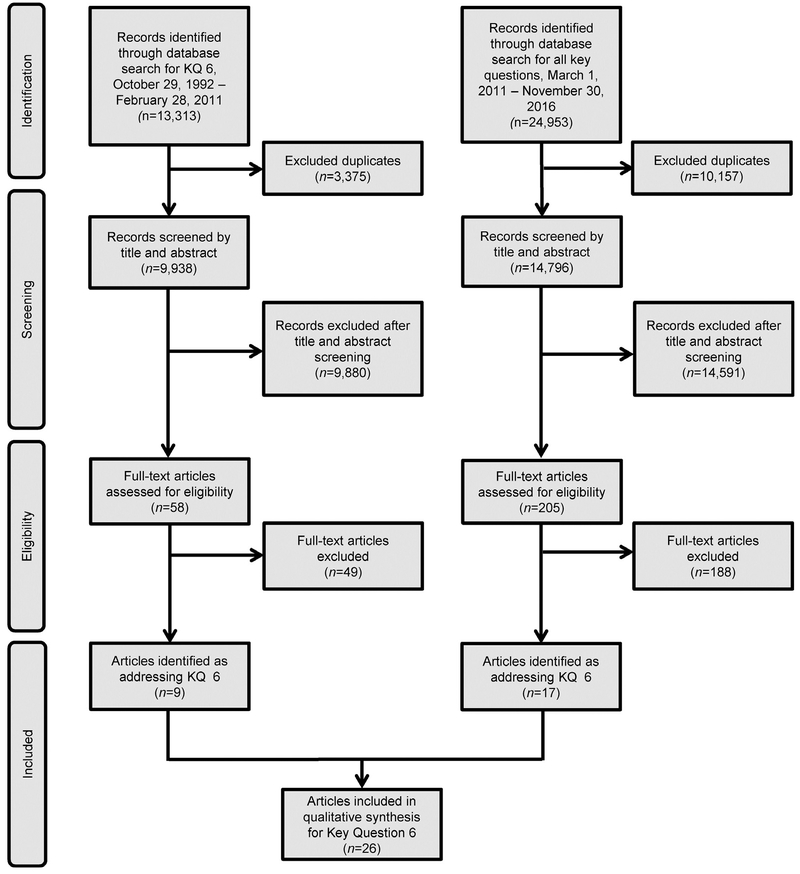

For the review series, a search was conducted of literature related to all KQs 1–6 published March 2011 or later. This review included only those articles addressing KQ 6. The search for literature related to all KQs 1–6 yielded 24,953 citations (Figure 2). Of these, 10,157 were excluded as duplicates. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for 14,796 citations, and 14,591 were excluded, primarily because they described research conducted outside the U.S. or similar setting, were unrelated to family planning, were not original research, or did not describe a contraceptive counseling intervention or client preferences. Full-text articles were reviewed for 205 records. Seventeen articles were identified as addressing KQ 6, in that they described aspects of care for which clients expressed a preference or which were associated with greater patient satisfaction or perceived quality of care. Another review in this issue examines outcomes associated with youth-friendly services.15 Although there is a minor overlap in findings (specifically regarding the importance of positive provider interactions and confidential services for youth), these two reviews provide uniquely useful bodies of evidence on (1) any family planning services designed specifically for youth and (2) preferences for contraceptive counseling among clients across the reproductive age range (15–45 years).

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for literature published March 1, 2011, through November 30, 2016, and limited search of earlier literature.

KQ, key question..

In the search for literature relevant to KQ 6 published prior to 2011, results included 13,313 citations (Figure 2). Of these, 3,375 were excluded as duplicates, and 9,938 citations were included in the review of titles and abstracts. Of these, 9,880 citations were excluded, primarily for the same reasons citations were excluded in the search of literature published since 2011. There were 58 full-text articles reviewed; the nine articles that met inclusion criteria were abstracted and results were integrated with results of 17 articles published since 2011, for a total of 26 articles describing client preferences published from October 1992 through November 2016. Two articles describe results from the same study and are discussed together in Evidence Synthesis.16,17

Appendix Table 3 (available online) describes key characteristics, research questions, results, design, and study quality of the 26 included articles. Twelve studies (from 13 articles) used qualitative methods to understand client preferences for contraceptive counseling, with sample sizes ranging from 14 to 42 women.3,16–27 Five studies used quantitative surveys to obtain descriptive information of counseling preferences (sample sizes ranging from 57 to 1,852 women).28–32 Three studies used surveys to examine associations between various factors and client preference, satisfaction, or perception of high quality of care (sample sizes ranging from 748 to 1,741 women).9,33,34 Four studies used mixed methods. Three of these studies had qualitative components and a survey or questionnaire (sample sizes ranging from 15 to 59 women),7,35,36 and one study used additional data from a chart review (n=7,801 women).37 One clinical trial of a counseling intervention (n=814 women) assessed client preferences as a secondary outcome.38 Female clients or potential clients of family planning services were the population for all studies, with nine studies assessing preferences of adolescent clients specifically.18,20,21,23,24,27,29,36,37 Other studies focused on women seeking prenatal and postpartum care,16,17,30 Latina immigrant women,19 young women who had experienced pregnancy,”56 college students,21 homeless women,35 women seeking abortion/8,31 and women or adolescents seeking emergency care.20,29,38 Four studies sought to assess differences in preferences between Latina, black, and white participants.3,9,25,31

Seventeen studies (from 18 articles) were conducted in urban settings in the u.s.3,16–20,22–25,29–31,35–38 Three studies about adolescents were conducted in secondary school settings,23,27,37 and one study was conducted on a suburban college campus.21 Six studies had geographically diverse samples (including urban, suburban, and rural participants) in multiple states or counties in the U.S.,7,9,28,32–34 including two with nationally representative samples.9,32 Two studies were conducted in midsized cities in Western Europe.26,27 Studies generally had moderate risk for bias and low generalizability to the predefined target population of women of reproductive age in the U.S.

During evidence synthesis, it was inductively determined that results aligned with four domains for client preferences. Results are organized according to these domains. Three domains are derived from Dehlendorf et al.,3 including (1) contraceptive information received in counseling; (2) the decision-making process; and (3) the relationship between providers and clients. An additional domain was addressed by a subset of studies: (4) the context in which contraceptive counseling is delivered (e.g., where, when, and with whom counseling conversations occur). Findings are described by domain and subdomain below. Table 1 depicts article findings by domain and subdomain.

Table 1.

Summary of Client Preferences for Contraceptive Counseling

| Domai1: Contraceptive Information | Domain 2: Decision-making process | Domain 3: Provider-client relationship | Domain 4: Context in which counseling is provided | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author and year | Comprehensive and relevant information | Preferred modes of communication | Visual models and aids | Respect for client autonomy | Provider involvement | Positive interpersonal dynamic | Continuity of care | Assurance of confidentiality | Preferences for provider professions and settings | Female providers | Preferred timing of counseing | Total sub-domains addressed in study |

| Becker and Tsui (2008)9 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Becker et al. (2009)25 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 8 | |||

| Brown et al. (2013)18 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 5 | ||||||

| Carvajal et al. (2017)19 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 5 | ||||||

| Chernick et al. (2016)20 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Dasari et al. (2016)35 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 4 | |||||||

| Dehlendorf et al. (2010)31 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Dehlendorf et al.(2013)3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 6 | |||||

| Guendelman et al.(2000)7 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Hickey and White (2015)21 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Johnson et al. (2015)36 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Lowe (2005)26 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Marshall et al. (2017)22 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Matulich et al. (2014)28 | ■ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Mollen et al. (2013)29 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Peremans et al.(2000)27 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 4 | |||||||

| Pilgrim et al. (2014)34 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Rubin et al. (2016)24 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Sangraula et al. (2017)23 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 6 | |||||

| Schwarzetal. (2013)38 | ■ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Soleimanpour et al. (2010)37 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Sonenstein et al. (1995)32 | ■ | ■ | 2 | |||||||||

| Weisman et al. (2002)33 | ■ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yeeand Simon (2011)16,17 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 6 | |||||

| Yee et al. (2O15)30 | ■ | ■ | ■ | 3 | ||||||||

| Total studies addressing sub-domain | 15 | 12 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

Domain 1: Contraceptive Information

Sixteen articles (from 15 studies) indicated client preference for receipt of detailed information about contraceptive methods.3,7,16–20,22–25,27,30,32,33,35 Eight studies (from nine articles) emphasized the importance to clients of personalized contraceptive information that met their individual needs and preferences.7,16–18,20,22,25,27,32 Studies reported on varied client priorities for contraceptive information. Information on side effects was most frequently reported as important to clients.3,16,18,19,23,25,27,35Other types of information desired included method efficacy,19,35 how to use a method,25 the mechanism of pregnancy prevention,23 and corrections to contraceptive misinformation.18,20,23 In two studies, adolescent participants expressed a need not to be overwhelmed with too much information.23,27

Twelve studies included results on client preferences for modes of communication for contraceptive information.3,16–18,20,22,23,25,27,29,30,35,38 In eight qualitative and mixed-methods studies, participants expressed wanting to receive written information to complement verbal information from providers.3,16–18,20,22,25,27,35

This information could be delivered at several opportunities surrounding the visit. In the study by Dehlendorf and colleagues,3 some participants indicated the desire to review written information before a visit to formulate questions for their provider. Likewise, Marshall et al.22 found that clients liked using an electronic contraceptive decision support tool before a visit, with some participants expressing desire to use the tool during or after the visit, as well. In two interview studies, participants described preference for seeing written materials during their visit.25,30 In Dasari and colleagues,35 participants liked receiving written materials to take with them after visits. Participants in four qualitative studies liked to access information from web sources that could complement counseling.3,16,18,20

Participants in two qualitative studies and a clinical trial preferred verbal over written communication about contraception.23,29,38 Adolescent participants in the study by Sangraula et al.23 preferred verbal communication specifically because of confidentiality concerns.

In seven studies, clients reported liking the use of visual models and aids during counseling.16–18,23–25,34,35 Dasari and colleagues35 showed participants a chart of contraceptive method efficacy.39 Participants reported liking the visual model and that it made it easier to compare method efficacy. In three studies, adolescent users of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) said they appreciated seeing models depicting LARC insertion.18,23,24 Participants in the study by Becker et al.25 appreciated seeing contraceptive method samples as visual aids. The survey study by Pilgrim and colleagues34 with Title X clients found that those who were not counseled using visual aids had lower odds of agreeing they received high quality care, compared with those counseled using visual aids (AOR=0.25, p<0.05).

Domain 2: The Decision-Making Process

Five studies explicitly described the importance of respect for patient autonomy in contraceptive decision making.16,23,25,26,31 In one study, clients reported a higher value for autonomy in contraceptive decisions versus other healthcare decisions.31

In the study by Pilgrim et al.,34 clients who reported that the provider mostly made the contraceptive decision had lower odds of agreeing that they received high-quality care, compared with those who made the decision alone (AOR=0.14,p<0.05). There was no significant difference between clients who made the decision together with their provider and those who made the decision alone. In the study by Dehlendorf and colleagues,3 black and Spanish-speaking Latina participants (as compared with white and English-speaking Latina participants) felt it was appropriate for providers to express a method preference only if requested by the patient or if clearly justified.

Mirroring the importance of autonomy, participants disliked provider pressure in their contraceptive decisions. Eight of the included studies addressed the topic of pressure, and in all eight studies, clients preferred that providers not pressure them to choose a particular method.3,7,17,19,22,23,25,35

Two studies examined women of color’s preferences related to directive counseling by exploring previous negative experiences of counseling.17,19 In the interview study by Yee and Simon,17 the sample of women of color described having negative experiences when counseling felt coercive, restrictive, or overbearing, and some connected these experiences to racial discrimination. In the study by Carvajal et al.19 with Latina immigrant women, participants disliked counseling that was paternalistic and focused on specific methods, and connected negative experiences to ethnic bias among providers.

Although results emphasized the importance of prioritizing patient autonomy, five studies exploring client preferences for provider involvement in decision making indicated that some involvement may be desirable to some clients.3,18,19,31,34 One specific approach to counseling discussed in three studies was shared decision making.3,19,31 In this model of counseling, the provider contributes his or her medical knowledge, while the client provides expertise on his or her own values and preferences.40 All three studies emphasized that clients preferred to then make the final contraceptive decision themselves.3,19,31

Domain 3: The Provider-Client Relationship

Nine studies (from ten articles) indicated the importance of positive interpersonal dynamics between clients and providers.3,16–19,23–25,36,37 Participants appreciated relationships with providers involving trust, patience, and listening. In six qualitative studies, including three with adolescents, participants preferred providers to be friendly with clients.3,16,18,23,25,37 Two qualitative studies found that clients saw positive relationships with providers as facilitators to learning information and receiving decision support during counseling.16,24 Adolescent participants in three studies,23,36,37 including one study specifically with young women who had experienced pregnancy,36 particularly valued non-judgmental attitudes from their providers. Women in the interview study by Becker and colleagues25 likewise emphasized the importance of non-judgmental provider attitudes when providers questioned clients about sexual behavior. In the interview study by Yee and Simon,17 participants described poor counseling as impersonal and uncaring.

Women expressed a preference for continuity of care in three studies.3,9,25 In the survey study by Becker and Tsui9 comparing client preferences of different racial/ethnic groups, English- and Spanish-speaking Latina participants were more likely than white or black participants to value continuity of care with their family planning provider.

Six qualitative studies with adolescents and young women found a preference for assurance of confidential services.19–21,23,36,37 Latina participants younger than age 18 years in the study by Carvajal et al.19 were especially concerned about confidentiality, compared with participants older than 18 years, and equated confidentiality of services with trust in provider. One additional interview study found confidentiality was generally important to women of reproductive age.25

Domain 4: The Context in Which Contraceptive Counseling Is Provided

Seven studies included results on the preferred types of providers or settings where contraceptive counseling occurs.9,21,26,27,29,32,37 Three studies addressed the receipt of counseling in school settings.23,27,37 In one study using focus groups with high school students, participants expressed that they liked school health centers because they found accessing care easier in schools than in outside settings.37 They also liked that the services were confidential and free, and they felt that the staff at school health centers were youth-friendly and non-judgmental.37 By contrast, in another study with secondary school students27 and one study with college students,21 participants preferred to learn about contraception from their own family physicians or gynecologists, and not from school health centers. In the study with secondary school students, which was conducted in Belgium, this was due to existing relationships with these doctors.27 In the study with college students in the U.S., this was due to a concern that confidentiality could be compromised in the school healthcare setting.21

Participants in the study by Sonenstein and colleagues32 preferred private physicians to HMOs or family planning or other clinics. In the survey study by Becker and Tsui,9 black and English-speaking Latina participants were more likely to prefer receiving contraceptive counseling in a general care setting, compared with a family planning setting, than were white participants (62%, 61%, and 50%, respectively, p<0.05). Although Spanish-speaking Latinas were most likely to prefer a general healthcare setting (69%), this was not significantly different from the reference group of white clients in multivariate analysis. By contrast, participants in one study in Britain preferred receiving care in a family planning clinic over a general care setting, because they perceived the family planning clinic was more focused on women,s experiences.26

Finally, in the study by Mollen et al.29 examining adolescent preferences for learning about emergency contraception in emergency departments, participants preferred learning from a doctor or nurse rather than a peer counselor. They also preferred for education to occur when seeking care related to sexual activity, but not when seeking care for reasons unrelated to sexual activity.

Four studies indicated participant preference for female over male providers.9,25–27 In the study by Lowe,26 participants preferred female providers because of their perceived personal knowledge of contraception. The interview study by Becker and colleagues25 also found a preference for female providers because of participant perception of superior knowledge among female providers compared with male providers, and participants’ greater comfort with female providers than male providers. In surveys, English- and Spanish-speaking Latinas had higher odds of preferring a female provider compared with white and black clients.9

Three studies focused on preferences for the timing of counseling in relation to other reproductive health care.16,28,30 In the study by Yee et al.30 of women who had received prenatal and postpartum care, 84% of participants reported a preference for contraceptive counseling both before and after delivery. Participants in a similar population indicated in interviews that they preferred provider-initiated counseling throughout the prenatal period, to give clients multiple opportunities to make a decision and “plan ahead.”16 In the survey study by Matulich and colleagues28 with abortion clients in Northern California, 64% did not want to talk about contraception on the day of their abortion procedure, with about half reporting this was because they already knew what method they wanted to use.

DISCUSSION

This review included 26 articles describing 25 studies related to client preferences for contraceptive counseling, including 17 articles published in March 2011 or later. A growing number of studies have addressed this topic in the years since 2011, in keeping with an increasing focus on patient centeredness in health care generally41 and family planning specifically.5

Eighteen studies (from 19 articles) provided information on clients, preferences for receiving contraceptive information.3,7,16–20,22–25,27,29,30,32–35,38 Results emphasized the value of comprehensive, personalized information to meet the needs and preferences of clients, including but not limited to information on side effects and method efficacy. This evidence suggests that to improve the client centeredness of counseling, providers might use tailored approaches to elucidate what information is most valuable to clients and deliver personalized counseling. Customizing the discussion in this way may also address time constraints that may affect counseling quality.10 Future research should explore how tailored approaches, such as decision aids and standardized questions to elicit client preferences, may impact patient experience.

Clients had varied preferences for modes of communication. Clients generally valued receiving written or electronic information supplementing verbal information.3,16–18,20,22,25,27,35 Visual aids were also useful to clients.16–18,23–25,34,35 The availability of multiple forms of written and visual information before, during, and after visits may accommodate clients, various preferences.

Twelve studies (from 13 articles) reported preferences related to the contraceptive decision-making process.37,16–19,22,23,25,26,31,34,35 Clients valued respect for their autonomy in making the final decision about contraception16,23,25,31 and emphasized dislike for provider pressure.3,7,17,19,20,22,23,25,35 This domain may be particularly salient for women of color, given that racial/ethnic bias in the promotion of highly effective methods, such as LARC, has been documented42 and that two included studies report perceived racial/ethnic discrimination in contraceptive counseling among women of color.17,19 Finally, multiple studies documented some clients desired some provider engagement in the decision-making process, with emphasis on the client making the final decision.3,16,19,23,34 This finding is consistent with results from a study published after the end date for this review (November 30, 2016), which found that patients who reported experiencing shared decision making were most satisfied with their counseling, compared with those who reported making the contraceptive decision by themselves, or who reported the provider making the decision.43

Twelve studies (from 13 articles) indicated client preferences for positive interpersonal dynamics with their providers.3,9,16–21,23–25,36,37 Confidentiality was also important in the counseling relationship, especially to adolescents.19–21,23,36,37 Although a positive relationship between medical professionals and those they care for is of value in all aspects of medical care, these results underscore their particular importance in the context of the personal and intimate decision-making process around contraception.

Finally, 11 studies included information on the context in which counseling is provided.9,16,21,25–30,32,37 Clients had varied preferences for the context of care, including receiving counseling inside or outside of school settings,23,27,37 in family planning or more general care settings,9,21,26,27,29,32 from female providers,9,25–27 and alongside other reproductive healthcare services.16,28,30 These results point to the importance of having diverse family planning providers and environments to meet clients’ needs.

Contraceptive care in the prenatal and postpartum period was well received by clients.16,30 Contraceptive counseling on the day of abortion was not desired by a majority of clients in one study.28 Future research could explore how best to meet the contraceptive needs of clients seeking abortion and when contraceptive counseling is best provided in that context.

A strength of this review is its comprehensive inclusion of studies of any design. This allowed for the inclusion of a diverse range of studies on client preferences for counseling, many including rich qualitative data. When synthesized in a review, this information offers insights to inform future programmatic efforts, interventions, and research.

Limitations

A limitation of many of the included qualitative studies is small sample size, and results have limited generalizability to the broader population of women of reproductive age. Some of these small studies offer valuable evidence on specific populations, such as women of color and Latina immigrant women. There is a lack of evidence, however, on preferences among other specific populations with particular needs, such as incarcerated women; women who use substances; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer clients; those in rural settings; and immigrant and refugee clients. An additional limitation is that included studies generally had moderate risk for bias. This was largely due to common recruitment methods for qualitative research (e.g., by flyer, conducting activities with existing groups) resulting in convenience samples.

CONCLUSIONS

The included studies document client preferences regarding the content of quality contraceptive counseling, including comprehensive, personalized information provision; decision-making support that prioritizes client autonomy; positive interpersonal relationships with providers; and diverse preferences for the context in which contraceptive counseling is provided. The included studies provide rich evidence that may inform future programs, interventions, and research, enhancing the experience of contraceptive counseling for family planning clients in the U.S.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lorrie Gavin, formerly Senior Health Scientist at the Office of Population Affairs, for spearheading the development of the 2014 Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations and the updated systematic reviews for supporting the recommendations.

This product was supported, in part, by contracts between the Office of Population Affairs and Atlas Research, Inc. (Nos. HHSP233201500126I, HHSP233201450040A). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Office of Population Affairs or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No financial or other disclosures of conflicts of interest were reported by the authors of this paper.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.006

REFERENCES

- 1.Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Creinin M, Ibrahim S. The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(l):91–96. 10.1089/jwh.2008.0976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dehlendorf C, Henderson JT, Vittinghoff E, et al. Association of the quality of interpersonal care during family planning counseling with contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215(l):78.el–78.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Kelley A, Grumbach K, Steinauer J. Women’s preferences for contraceptive counseling and decision making. Contraception. 2013;88(2):250–256. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dehlendorf C, Fox E, Sobel L, Borrero S. Patient-centered contraceptive counseling: evidence to inform practice. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2016;5(l):55–63. 10.1007/sl3669-016-0139-l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-04):l–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker A Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. BMJ. 2001;323(7322):1192 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guendelman S, Denny C, Mauldon J, Chetkovich C. Perceptions of hormonal contraceptive safety and side effects among low-income Latina and non-Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(4):233–239. 10.1023/A:1026643621387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker D, Koenig MA, Kim YM, Cardona K, Sonenstein FL. The quality of family planning services in the United States: findings from a literature review. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39(4):206–215. 10.1363/3920607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker D, Tsui AO. Reproductive health service preferences and perceptions of quality among low—income women: racial, ethnic and language group differences. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(4):202–211. 10.1363/020208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akers AY, Gold MA, Borrero S, Santucci A, Schwarz EB. Providers’ perspectives on challenges to contraceptive counseling in primary care settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(6):1163–1170. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tregear SJ, Gavin LE, Williams JR. Systematic review evidence methodology: providing quality family planning services. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 suppl 1):S23–S30. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zapata LB, Tregear SJ, Curtis KM, et al. Impact of contraceptive counseling in clinical settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2 suppl 1):S31–S45. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone. New York, NY: UN Development Programme; Published 2016. 10.18356/b6186701-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3):21–35. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brittain AW, Loyola Briceno AC, Pazol K, et al. Youth-friendly family planning services for young people: a systematic review update. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(5):725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yee L, Simon M. Urban minority women’s perceptions of and preferences for postpartum contraceptive counseling. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(l):54–60. https://doi.org/10.llll/j.1542-2011.2010.00012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yee LM, Simon MA. Perceptions of coercion, discrimination and other negative experiences in postpartum contraceptive counseling for low-income minority women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(4): 1387–1400. 10.1353/hpu.2011.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MK, Auerswald C, Eyre SL, Deardorff J, Dehlendorf C. Identifying counseling needs of nulliparous adolescent intrauterine contraceptive users: a qualitative approach. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52 (3):293–300. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvajal DN, Gioia D, Mudafort ER, Brown PB, Barnet B. How can primary care physicians best support contraceptive decision making? A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of Baltimore Latinas. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(2):158–166. 10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernick LS, Schnall R, Stockwell MS, et al. Adolescent female text messaging preferences to prevent pregnancy after an emergency department visit: a qualitative analysis. J Medical Internet Res. 2016; 18 (9):e261 10.2196/jmir.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickey MT, White J. Female college students’ experiences with and perceptions of over-the-counter emergency contraception in the United States. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(l):28–32. 10.1016/j.srhc.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall C, Nuru-Jeter A, Guendelman S, Mauldon J, Raine-Bennett T. Patient perceptions of a decision support tool to assist with young women’s contraceptive choice. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(2):343–348. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangraula M, Garbers S, Garth J, Shakibnia EB, Timmons S, Gold MA. Integrating long-acting reversible contraception services into New York City school-based health centers: quality improvement to ensure provision of youth-friendly services. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(3):376–382. 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.ll.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin SE, Felsher M, Korich F, Jacobs AM. Urban adolescents’ and young adults’ decision-making process around selection of intrauterine contraception. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(3):234–239. 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker D, Klassen AC, Koenig MA, LaVeist TA, Sonenstein FL, Tsui AO. Women’s perspectives on family planning service quality: an exploration of differences by race, ethnicity and language. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41(3):158–165. 10.1363/115809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe P Embodied expertise: women’s perceptions of the contraception consultation. Health. 2005;9(3):361–378. 10.1177/1363459305052906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peremans L, Hermann I, Avonts D, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Contraceptive knowledge and expectations by adolescents: an explanation by focus groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40(2):133–141. 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matulich M, Cansino C, Culwell KR, Creinin MD. Understanding women’s desires for contraceptive counseling at the time of first-trimester surgical abortion. Contraception. 2014;89(1):36–41. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mollen CJ, Miller MK, Hayes KL, Wittink MN, Barg FK. Developing emergency department—based education about emergency contraception: adolescent preferences. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(11):1164–1170. 10.1111/acem.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yee LM, Farner KC, King E, Simon MA. What do women want? Experiences of low-income women with postpartum contraception and contraceptive counseling. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2015;2(5):191 10.4172/2376-127X.1000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dehlendorf C, Diedrich J, Drey E, Postone A, Steinauer J. Preferences for decision-making about contraception and general health care among reproductive age women at an abortion clinic. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(3):343–348. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonenstein FL, Ku L, Schulte MM. Reproductive health care delivery. Patterns in a changing market. West J Med. 1995;163(3 suppl 1):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisman CS, Maccannon DS, Henderson JT, Shortridge E, Orso CL. Contraceptive counseling in managed care: preventing unintended pregnancy in adults. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12(2):79–95. 10.1016/S1049-3867(01)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilgrim NA, Cardona KM, Pinder E, Sonenstein FL. Clients’ perceptions of service quality and satisfaction at their initial Title X family planning visit. Health Commun. 2014;29(5):505–515. 10.1080/10410236.2013.777328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dasari M, Borrero S, Akers AY, et al. Barriers to long-acting reversible contraceptive uptake among homeless young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(2):104–110. 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KM, Dodge LE, Hacker MR, Ricciotti HA. Perspectives on family planning services among adolescents at a Boston community health center. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28(2):84–90. 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soleimanpour S, Geierstanger SP, Kaller S, McCarter V, Brindis CD. The role of school health centers in health care access and client outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1597–1603. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.186833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz EB, Burch EJ, Parisi SM, et al. Computer-assisted provision of hormonal contraception in acute care settings. Contraception. 2013;87 (2):242–250. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Effectiveness of family planning methods, www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/unintendedpregnancy/pdf/Family-Planning-Methods-2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 16, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sei Med. 1997;44(5):681–692. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomez AM, Fuentes L, Allina A. Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspeet Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):171–175. 10.1363/6el614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, Steinauer J. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95 (5):452–455. 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.