Abstract

Objective:

This study examined trends in familial transitions by maternal education and whether transitions rose because of changes in prevalence (the share of children exposed to a relationship state, either marriage or cohabitation) or churning (the number of entrances and exits conditional on being exposed to a relationship state).

Background:

Children’s experiences of transitions, an important predictor of well-being, have leveled off in recent decades. Plateauing in transitions may reflect heterogeneity by socioeconomic status.

Method:

Data came from the National Survey of Family Growth on firstborn children observed from ages 0 to 5 among mothers aged 15 to 34 at the time of the child’s birth (N = 7,265). Kitagawa methods decomposed changes in transitions into those attributable to changes in prevalence and churning. Analyses were conducted separately by maternal education.

Results:

Children born to lower and moderately educated women experienced an increase in transitions because cohabitation increased in prevalence rather than a change in the number of exits and entrances from cohabiting unions. Among this disadvantaged group, children exposed to cohabitation experienced much more churning than children exposed to marriage. Children born to mothers with a 4-year degree did not experience an increase in transitions and predominantly experienced stable parental marriages.

Conclusion:

Transitions only plateaued for children born to highly educated mothers, whereas transitions rose for less-advantaged children. Transitions appear to be another aspect of early family life experiences that contributes to diverging destinies.

Keywords: children, cohabitation, marriage, relationship dissolution, social class, transitions

Since the mid-1990s, cohabitation, which is less stable than marriage, went from rare to commonplace, suggesting greater increases in family disruption (Manning, Brown, & Stykes, 2015; Rackin & Gibson-Davis, 2012). Despite the increase in cohabitation, however, transitions appeared to have plateaued in the early 21st century (Brown, Stykes, & Manning, 2016). One explanation for the leveling off in transitions is that cohabitation has become more stable and has evolved to become similar to marriage in durability (Brown et al., 2016).

As we set forth, however, the evidence for a reversal in trends in familial transitions is likely divided by socioeconomic status (SES; measured here by maternal education). As informed by the diverging destinies perspective (McLanahan, 2004), which highlights the importance of SES in determining children’s trajectories, trends in mothers’ unions by SES likely signal growing class divides in family transitions. Mothers without a 4-year college degree, as opposed to their more-educated peers, are increasingly choosing cohabitation over marriage as a childbearing context (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014). In contrast, mothers with at least a bachelor’s degree generally choose marriage as a birth context, with only a slight increase in those who have a cohabiting birth. Moreover, marriages among highly educated parents have become more stable (Isen & Stevenson, 2011). Thus, the plateauing in the level of family transitions could have arisen because children from lower SES groups are facing an increase in transitions that is being offset by a decrease in transitions for those of higher SES.

A contribution of our study is to investigate how variation in transitions by maternal SES is the product of two potentially offsetting factors: prevalence and churning. Prevalence is the proportion of children exposed to a maternal relationship state (e.g., marriage or cohabitation), and churning is the number of entrances and exits children in that relationship state experienced. These two factors can move independently of each other, resulting in an increasing, decreasing, or a null change in transitions. Transitions could increase if churning within cohabitation remains the same, but cohabitation’s prevalence has risen (resulting in a larger pool of children experiencing cohabitation and its associated churning). Transitions could be flat if a greater share of children experienced parental cohabitation, but those who experienced it were less likely to see it dissolve. Finally, transitions could decrease if the prevalence of cohabitation remains the same, but churning within cohabitation has lessened.

Socioeconomic variation in family transitions likely reflects differential changes over time in the prevalence and churning of cohabitation and marriage. Among children born to less and moderately educated mothers, transitions will likely have increased because of the rapid increase in the prevalence of cohabitation among these groups (Manning et al., 2015). Cohabitation and marital churning may have also changed, but not enough to offset the large increases driven by changes in prevalence. Children born to better educated mothers, in contrast, are likely to have seen little change over time in transitions. For these children, cohabitation likely remains a rare union state, and any increase in cohabitation will likely be offset by decreased marital churning (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Martin, 2006).

To address these issues, we use data from the National Survey of Family Growth, including the most recently available data extending from 2013 to 2015, and follow cohorts of firstborn children born between 1985 and 2010 until their fifth birthday. We chose the first 5 years of life as it represents a critical developmental window (Elder, 1998; Phillips & Shonkoff, 2000). We provide the first analysis of the following questions: What are the trends in family transitions within children’s socioeconomic groups? Do these trends reflect increasingly diverging experiences by socioeconomic background? Within each socioeconomic group, what amount of changes in transitions is accounted for by changes in prevalence versus changes in churning? By answering these questions, we provide the first evidence of how trends in transitions are moderated by maternal education. Our results suggest that socioeconomic divergence in transitions is another dimension by which children experience diverging destinies.

Background

Family transitions (e.g., parental entrances and exits from a coresidential union) are important because they may have deleterious effects on child–parent routines, family dynamics, and parent–child conflicts (Beck, Cooper, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010; Coleman, Ganong, & Fine, 2000). Transitions also have been negatively correlated with child well-being, although the association may be stronger for behavioral, rather than cognitive, outcomes (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Magnuson & Berger, 2009).

Child age and the number of transitions experienced are important moderators of the effects of transitions. Children who are preschool age, relative to those who are older, may be at increased risk when families change composition (Cavanagh & Huston, 2008; Ryan & Claessens, 2013). The first 5 years of life are a critical developmental period for physical and socioemotional development (Elder, 1998), and young children may be particularly vulnerable to changes in family composition, resources, and dynamics. Multiple transitions, not surprisingly, may present particular risks for children; it is unclear if this effect is linear (e.g., if four transitions are worse than three), but research has found that children with two or more transitions are at increased risk of adverse outcomes relative to children exposed to just one transition (Osborne & McLanahan, 2007; Wu & Thomson, 2001).

In the early part of the 21st century, levels of transitions were relatively high. Between 25% and 55% of children born in the 1980s and 2000s experienced at least one transition by age 5, with exposure rising marginally as they aged (Cavanagh & Huston, 2006; Lee & McLanahan, 2015; Magnuson & Berger, 2009; Meadows, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008). Most children who experience transitions experience only one change, but a nontrivial minority—between 10% and 20%—will likely experience multiple transitions (Cavanagh & Huston, 2006; Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Lee & McLanahan, 2015). Unmarried mothers and disadvantaged groups, including children born to non-White women and those without any postsecondary training, experience more transitions than others (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Osborne, Manning, & Smock, 2007).

Through most of the last half of the 20th century, familial transitions increased, driven in the 1970s and 1980s by the rise in the divorce rate and in the 1990s by the increasing prevalence of cohabitation (Bumpass & Lu, 2000). Since the 1990s, however, transitions have plateaued (Brown et al., 2016). Comparing the early to mid-1990s and the early to late 2000s, Brown et al. (2016) found that the number of transitions children experienced at their fifth birthday remained flat at about 0.4 (notably, transitions increased for Black children). During the same time, others found that after the birth of a child the stability of a maternal union had not changed (Musick & Michelmore, 2015).

Trends in transitions may be leveling off because of decreases in the churning of cohabitation. As cohabitation has shifted from an avant-garde living arrangement to a pervasive parental relationship state, it may function similar to marriage in terms of its prevalence and stability (Kiernan, 2001). As cohabitation has become mainstream, it is increasingly subject to the same legal issues and social norms that make dissolving a marriage difficult. Moreover, as more parents cohabit, they may become increasingly representative of the larger pool of parents, suggesting that cohabiting parents may not be as negatively selected as they once were. In short, the increasing “stickiness” of cohabitation, as well as shifts in the demographics of those who have children within cohabitation, suggest that cohabitation has become a more durable union.

Previous work on the plateauing of transitions has focused on racial and ethnic differences (Brown et al., 2016), but good theoretical reasons exist to suppose that trends in transitions may be moderated by maternal SES. As informed by the diverging destinies theory (McLanahan, 2004), maternal SES informs relationship trajectories with the implication that trends in familial transitions are increasingly diverging by SES. Higher SES parents are increasingly older at first birth (Amato, Booth, McHale, & Van Hook, 2015), leaving more time to vet potential partners and develop high-quality relationships and stable careers, all of which may lead to fewer transitions over time. Lower and moderate SES parents, however, have seen less of an increase in age at first birth and have seen declines in the availability of steady well-paying jobs, particularly for men (Amato et al., 2015; Cherlin, 2014). Young parenthood, when combined with labor market uncertainty, may contribute to declines in relationship quality and more relationship churning (Conger et al., 1990; Manning, Smock, & Majumdar, 2004).

Maternal SES not only informs the duration of unions but also the type of union parents choose. Higher SES mothers, relative to their more disadvantaged peers, have higher incidences of marital births and higher incidences of marriage following a nonmarital birth; mothers without a college degree, however, are more apt to choose cohabitation over marriage as a birth context and are less likely to marry either before or after a birth (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Lundberg, Pollak, & Stearns, 2016; Osborne, 2005). Furthermore, the SES gap in union choice has grown over time (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Isen & Stevenson, 2011; Manning et al., 2015).

The fraction of mothers who choose a particular union is important because it determines the number of transitions a cohort of children will encounter. The intuition is that transitions are a function of both the number of entrances and exits from a union, but also of the fraction of children exposed to that union (who are thus at risk of experiencing relationship churning). To understand this, consider the model where T = transitions, P = prevalence of unions, and C = churning (e.g., number of exits or entrances into a union, conditional on being exposed to a union). For a given cohort of children, the number of transitions is T = P × C. In the case of two union types (e.g., marriage or cohabitation) then total transitions is the sum of the prevalence and churning associated with each of those unions. If m = marriage and c = cohabitation, then

Because T has two components, any changes in T can be decomposed into those arising from changes in prevalence or changes in churning. For example, assume a baseline number of transitions of 1, in which 80% experienced marriage and 10% experienced cohabitation, and churning associated with marriage was 1 and for cohabitation 2 (i.e., T = 0.8 × 1 + 0.1 × 2). Suppose the prevalence of marriage dropped to 40% while the prevalence of cohabitation increased to 50%, then T = 1.4, a 40% increase in transitions over baseline. Note, though, that the increase arises because cohabitation became more prevalent, not because relationship churning increased.

With this in mind, it is possible to see how trends in transitions could have plateaued if changes in prevalences are offset by changes in churning. Assume, as shown previously, that mean transitions for a cohort of children was 1. For a later cohort, suppose, as stated previously, that Pm = 0.4, Pc = 0.5, and Cm = 1, but churning for cohabitation declined to 1.2. This later cohort would have the same number of transitions as the earlier cohort, for example, T = (0.4 × 1) + (0.5 × 1.2). Thus, although children in the later cohort were more likely to experience cohabitation, they saw no net increase in transitions because cohabiting churning neared the levels of marital churning.

We use this decomposition analysis to inform how familial transitions have changed by maternal SES. We hypothesize that children born to the less advantaged will have seen an increase in transitions. This increase is likely because the rapidly rising prevalence of cohabitation may only be slightly offset by a modest decline in its churning (Manning et al., 2015; Musick & Michelmore, 2015). We do not expect changes in marital churning to contribute much to the rise in transitions (Martin, 2006). For the most advantaged, we do not expect to see changes in transitions because the small increase in the prevalence of cohabitation is expected to have been offset by declines in marital churning (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Martin, 2006).

Data and Methods

Data

Data come from female respondents in the 1995, 2002, 2006 to 2010, 2011 to 2013, and 2013 to 2015 waves of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The NSFG is one of the premier sources of U.S. data on marriage, cohabitation, fertility, and health. It is a nationally representative survey of individuals aged 15 to 44, with generally high response rates (NSFG, 2015). We did not use earlier waves of the NSFG because complete cohabitation histories were not collected. Male respondents were excluded because data collection for men did not begin until 2002. We used the NSFG fertility and relationship history modules to construct cohabiting and marital transitions from the time of a mother’s first birth until that child reached the age of 5.

Our sample was restricted to first births to mothers aged between 15 and 34 and whose child’s birth occurred within 5 to 10 years of the survey wave (e.g., births that occurred between 1985 and 2010). These restrictions were imposed following others who have worked with multiple waves of the NSFG (Raley & Wildsmith, 2004) to avoid truncation bias. Truncation bias arises because the age restrictions of the NSFG can lead to a sample that is skewed toward younger mothers at earlier time periods (Rindfuss, Palmore, & Bumpass, 1982). For example, the only births observed in 1980 (i.e., 15 years prior to the 1995 NSFG) would be to mothers aged 29 or younger, as a mother who was 30 in 1980 would be 45 in 1995 and would not be included in the 1995 NSFG’s sampling frame. Because the mid-30s is an important fertility window for the highly educated, we eliminated births that occurred more than 10 years before survey waves.

Restricting the sample to births that occurred at least 5 years prior to the survey wave ensures that the sample is not right censored (which occurs if observations are followed for different lengths of time). We chose 5 years because the preschool years are an important developmental period (Elder, 1998; Phillips & Shonkoff, 2000; Ryan & Claessens, 2013) and also because it allows us to include children born until 2010. If we had followed children until age 12, then the latest cohort we could observe and also avoid right censoring is 2003.

Of the 19,524 women who had first births between 1985 and 2010, 11,863 were excluded because their first birth occurred more than 10 years or less than 5 years before a survey wave. Of the remaining 7,661, 323 were excluded because they were younger than age 15 or older than age 34 at first birth. Less than 1% (73) were excluded because they had missing union start or end dates. The final sample was 7,265 first births. When compared with our analytical sample, excluded mothers were demographically similar in terms of age, race, education, and union status at birth. We note that the retrospective data collected by the NSFG can suffer from recall bias. Recall bias is less concerning here because we only observe events within 10 years of the survey; moreover, we do not believe that retrospective recall has changed dramatically over time.

Measures

The main variable of interest was the number of transitions firstborn children experienced between ages 0 and 5. The number of transitions was calculated by summing the number of entrances and exits into marital and cohabiting unions during the first 60 months of the child’s life using maternal reports of dates of marriages, cohabitations, and first births.

Transitions had two components: prevalence and churning. Prevalence was measured by the share of children exposed to a maternal relationship state (either marriage or cohabitation). Churning was measured by the number of entrances and exits into unions conditional on the child being exposed to that union. As we were interested in transitions from the child’s perspective, we only counted transitions and unions if they involved the introduction of a new partner. Thus, we would not count the situation where the same two individuals move from cohabitation to marriage as a transition. Because the NSFG only recently began collecting data on paternal biological ties, we do not separate out transitions by the biological tie to the child.

We grouped children into one of the following two possible mutually exclusive maternal relationship states: cohabitation and marriage. In our classification, marriage superseded cohabitation, such that children in the cohabiting category experienced at least one maternal cohabitation, but did not experience maternal marriage. Children in the marriage category had to have experienced at least one maternal marriage; their mother may have also cohabited with another partner. Given that our two relationship states are mutually exclusive, we avoid the issue of double counting (decomposition analysis cannot be done where cases are double counted). We could not constitute a separate category for mothers who married one man but cohabited with another because only 4% of mothers fell into this category. Supplementary analyses indicated that excluding the 4% of these double-counted cases had no substantive effect on our results.

We give some examples to illustrate these definitions. Suppose a child was born to a married mother who remained married throughout our observation period. The child is classified in the marital group and contributes zero transitions to marital churning. Now suppose a child was born to a mother who, at the time of the birth, was neither married nor cohabiting. If the mother subsequently cohabited and then married the same man, that child is classified in the marital group to calculate prevalence and contributes one transition to the marital churning measure. If a similar unpartnered mother subsequently had a cohabiting relationship that ended, then her child would be classified in the cohabiting group, and the child contributes two transitions to the cohabitation churning measure. Finally, if a mother was single at birth, cohabited with one man, but ended that relationship and married another man, then the child is classified in the marital group, and her three transitions are counted in the measure of marital churning.

A primary covariate of interest was maternal education, which refers to the mother’s education at the time of the survey and was used to stratify analyses (detailed educational measures at the time of birth were not collected). Following others (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Isen & Stevenson, 2011), we divided maternal education into three categories: (a) women with a high school degree or less (termed low educated), (b) women with an associate’s degree or some college but no degree (moderately educated), and (c) women with at least a bachelor’s degree (highly educated). The low-educated group included women with and without a high school diploma because there were too few cases of women without a high school diploma to produce reliable estimates. Trends in transitions were also similar for women with and without a high school degree.

We rely on maternal, rather than paternal, education to proxy SES because paternal education data were not routinely collected. Reliance on maternal education alone could lead to misclassifications if low SES mothers were partnering with high SES men who contributed large amounts of resources to the household. Given high (and increasing) rates of educational homogamy (Mare, 2016), however, we do not believe this to be the case.

Year of birth was divided into one of the following five cohorts: 1985 to 1989, 1990 to 1994, 1995 to 1999, 2000 to 2004, and 2005 to 2010. The results were not sensitive to changing cohorts by 1 year (e.g., 1985–1990). The 1990 to 1994 cohort had fewer respondents than other cohorts because our sample restrictions and timing of surveys excluded children born in 1991. Those born in 1991 could not be observed in the 1995 NSFG (they would have been born 4, not 5, years before the survey) nor could data be gathered in the 2002 wave (they would have been born 11, not 10, years before the survey). This problem only existed for the 1991 cohort because later waves gathered data at shorter intervals.

Analytic Strategy

We first show weighted estimates of the number of family transitions and the prevalence and churning of relationship states by cohort and mother’s education. We examined if these measures have changed compared to the first cohort (i.e., children born between 1985 and 1989) using adjusted Wald tests and weighted regression. Findings were weighted to be representative of U.S. mothers aged 15 to 34 years at the time of first birth. Because all children were observed into their fifth birthday and entered the risk pool at the same time (at birth), data were not left or right censored.

We chose to use cohort rather than period measures because the rate of transitions is likely not consistent across cohorts. Given that period measures combine cohorts to estimate transitions, these measures assume that the number of transitions is constant across cohorts. As an example, period estimates of transitions for 2015 could be obtained by using age-specific estimates of transitions for children observed from ages 0 to 5 between 2010 and 2015. Age 5 rates would come from the 2005 to 2010 cohort (observed at age 5 in the years 2010–2015). Age 1 rates, however, would come from cohorts born between 2009 and 2014 (observed at age 1 in the years 2010–2015). Thus, the period measure would come from nearly a 10-year span of cohorts and would not accurately represent cohort transitions unless rates were similar across cohorts.

We used Kitagawa decomposition methods to decompose how much of the changes in family transitions were attributable to changes in the prevalence and churning of relationships. The change in transitions is a function of the change in the churning for any relationship state times the average change in prevalence plus the change in prevalence times the average change in churning. Equation 1 indicates how the change in transitions between two time periods (1985–1989, denoted 85, and 2005–2010, denoted 05) can be decomposed into two component parts:

| (1) |

where T = transitions, r = relationship state, C = churning, and P = prevalence. The equation decomposes the total change into changes in churning (for a given relationship state if prevalence of that state was at the average of these cohorts) and into the changes in the prevalence (if the churning of that state was at the average of the cohorts).

In supplementary models, we examined if gaps between educational groups changed from the first cohort to the last (e.g., if slopes of changes in transitions between these cohorts significantly differed for the lowand high-education groups). Statistically significant results (available on request) show that differences between groups had changed between the first and last cohorts as indicated in pooled models with interactions (by cohort and maternal education).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics by cohort. Bold numbers show significant differences (p < .05) from the 1985 to 1989 cohort, and italicized numbers show marginally significant differences (p < .10). Trends in marriage and cohabitation were as expected: Married births decreased, increasingly replaced by cohabiting births. In the earliest cohort, 69% of births were to married mothers, whereas only 5% were to cohabiting mothers. By 2005 to 2010, marriage had declined by 17%, to 57% of births, and cohabitation was up by 331%. Over time, children were also less likely to experience a marital union, and more likely to experience a cohabiting union. By the last cohort, one third of firstborn children experienced a maternal cohabitation within the first 5 years of their life, a near tripling of children’s exposure to cohabitation in just 25 years.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample by Year of Child’s Birth (N = 7,265)

| Variables | Year of birth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | |

| Relationship status at birth | |||||

| Married | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.57 |

| Cohabiting | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.22 |

| Single | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Child’s mothera | |||||

| Married | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.64 |

| Cohabited | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.33 |

| Educationb | |||||

| Low | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| Moderate | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.35 |

| High | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| White | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Black | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Hispanic | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Age at birth | 24.1 | 24.1 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 24.1 |

| (4.70) | (4.92) | (5.04) | (4.78) | (4.87) | |

| Sample size | 1,580 | 942 | 1,344 | 1,949 | 1,450 |

Note. Bolded estimates show significant differences (p < .05) and italicized show marginal differences (p < .10) from the 1985 to 1989 cohort. Standard deviations for age are in parentheses. Estimates are weighted.

Within first 5 years of child’s life.

Measured at time of survey.

Low = mother has a high school diploma or less; moderate = mother has some postsecondary training; high = mother has a bachelors’ degree or more.

Reflecting the secular trend of increasing education, mothers of children born later were more likely to be moderately and highly educated at the time of the survey than those of children born in the earliest cohort. Over time, mothers were less likely to be White and more likely to be Hispanic. Age at first birth is constant across cohorts, an artifact of our sample restrictions.

Transitions for Children by Maternal Education

The next set of results analyzed differences in transitions for the full sample and by maternal education (see Table 2). The results are presented for marriage and cohabitation combined. Among all children, the average number of transitions remained relatively constant at 0.50 for all birth cohorts except for the 2005 to 2010 cohort, when it marginally increased to 0.59. Furthermore, across cohorts, about one third of children experienced at least one transition (results not shown).

Table 2.

Number of Transitions by Year of Birth and Maternal Education

| Maternal education | Year of birth | Change in transitionsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | Difference | % change | n | |

| All | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.104 | 21.3 | 7,265 |

| (1.04) | (1.01) | (0.98) | (0.97) | (0.86) | ||||

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| Low | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.181 | 30.1 | 3,680 |

| (1.17) | (1.17) | (1.22) | (1.18) | (1.10) | ||||

| Moderate | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.229 | 47.7 | 2,161 |

| (1.00) | (0.91) | (0.93) | (0.97) | (0.86) | ||||

| High | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 1.4 | 1,424 |

| (0.58) | (0.51) | (0.42) | (0.44) | (0.39) | ||||

Note. Bolded estimates show significant differences (p < .05) and italicized show marginal differences (p < .10) from the 1985 to 1989 cohort. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Estimates are weighted.

Change between 1985 to 1989 and 2005 to 2010 cohort.

The results by education indicated that in every cohort, children born to the highly educated experienced fewer transitions than children born to the low and moderately educated. In 2005 to 2010, for example, the number of transitions was 0.78 for the low-educated group, 0.71 for the moderately educated, and 0.19 for the highly educated. Over time, the low and moderately educated also had a large, statistically significant increase in transitions (30% and 48%, respectively), whereas transitions for the highly educated remained essentially flat (1%). As these differential increases by maternal education suggested, the number of transitions for children born to the low and moderately educated converged over time and increasingly diverged from the number of transitions for children born to highly educated mothers.

The next set of results presents the two factors that underlie levels of familial transitions, prevalence and churning (see Table 3). The results are presented by maternal education and by birth cohort, and prevalence and churning are shown separately for marriage and for cohabitation. For instance, for children born in 1985 to 1989 to the low educated, 76% experienced marriage, and among that 76%, the average number of entrances and exits (or churning) was 0.58.

Table 3.

Prevalence and Churning of Relationship Type by Year of Birth and Maternal Education

| Panel A. Low (n = 3,680) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | % change | |

| Relationship state | ||||||

| Marriage | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.47 | −39 |

| Churning | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 10 |

| Cohabitation | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 292 |

| Churning | 1.43 | 1.46 | 1.38 | 1.25 | 1.14 | −20 |

| Panel B. Moderate (n = 2,161) | ||||||

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | % change | |

| Relationship state | ||||||

| Marriage | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.62 | −22 |

| Churning | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 36 |

| Cohabitation | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 205 |

| Churning | 1.63 | 1.24 | 1.29 | 1.24 | 1.22 | −25 |

| Panel C. High (n = 1,424) | ||||||

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2004 | 2005–2010 | % change | |

| Relationship state | ||||||

| Marriage | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.91 | −3 |

| Churning | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.12 | −34 |

| Cohabitation | ||||||

| Prevalence | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 279 |

| Churninga | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Note. Bolded estimates show significant differences (p < .05) and italicized show marginal differences (p < .10) from the 1985 to 1989 cohort. Estimates are weighted.

Estimates were unreliable because of small sample sizes and are not shown.

Trends in the prevalence and churning of marriage have diverged by maternal education. For children born to the lower two education groups, the prevalence of marriage was down, whereas churning among children who experienced marriage was up (albeit nonsignificantly). Among children born to low-educated mothers, for example, the prevalence of marriage declined by 39% (from 0.76 to 0.47), with a nonsignificant increase in churning (0.58 to 0.64). In contrast, children born to the highly educated experienced no decline in the prevalence of marriage (more than 90% for all cohorts) with a nonsignificant decrease in churning (0.19 to 0.12). Moreover, the 2005 to 2010 cohort difference in marriage prevalence between low-educated and highly educated mothers (0.91 − 0.47, or 0.44) was significantly larger than the difference in the 1985 to 1989 cohort (0.17). Likewise, the 2005 to 2010 cohort difference in the levels of churning among children who experienced marriage between moderately and highly educated mothers (0.54 − 0.12, or 0.42) was significantly larger than it was in the 1985 to 1989 cohort (0.21). Thus, children born to the most educated were increasingly more likely to experience marriage as compared to children born to the least educated, and more likely to experience less marital churning than children born to the moderately educated.

Maternal education also moderated the prevalence and churning seen for cohabitation. For our observed cohorts, children born to the lower two education groups experienced large increases in the prevalence of cohabitation, with more modest declines in churning. The prevalence of cohabitation for children born to the least educated rose 292% from the earliest time period to the last (from 11% to 42%), with a 20% decline in churning. Children born to the moderately educated also experienced a 205% increase in prevalence, with a 25% decrease in churning. Children of the most educated also saw a large rise in the prevalence of cohabitation, but this increase belied the rarity of the event (only 7% of these children born in the 2005–2010 cohort experienced cohabitation). Moreover, the share of children born to the highly educated who experienced cohabitation was so small that we were unable to calculate reliable churning estimates for them. Overall, our results indicated that children of low and moderate SES mothers have experienced more cohabitation over time, with some increase in the union’s durability, whereas children of high SES mothers remained relatively unlikely to experience cohabitation.

Within the two lower educated groups, evidence showed convergence in the levels of churning between marriage and cohabiting. For children born to the least educated, in 1985 to 1989, churning levels were 2.5 times as high for cohabitation as those for marriage (1.43 for cohabitation vs. 0.58 for marriage); by 2005 to 2010, the churning levels were 1.8 times as high (1.14 vs. 0.64). Children born to the moderately educated saw an even larger decrease in the cohabiting–marital churning gap between the earliest and last cohorts. This narrowing in the cohabiting–marital churning gap was statistically significant for both education groups. Even so, across cohorts, children exposed to cohabitation still experienced more churning than those exposed to marriage. For the most recent cohort, for example, children born to the moderately educated who were exposed to cohabitation experienced more than twice as much churning when compared with those exposed to marriage.

For all children, transitions from marriage contributed proportionally less, and cohabitation contributed proportionally more, to total transitions over time. Recall that total transitions equals the sum of prevalence and churning for marriage and cohabitation (i.e., T = Pm × Cm + Pc × Cc). Thus, for children born in 1985 to 1989, the majority of the total transitions came from children exposed to marriage (74%, 66%, and 93%) for those born to the low, moderately, and highly educated, respectively (i.e., for children born to low-educated mothers, transitions from marriage equals0.76 × 0.58 = 0.45, 0.45/0.60 = 74%). By 2005 to 2010, the proportion of transitions attributable to marriage declined substantially, ranging from 39% for children born to low-educated mothers to 59% for children born to highly educated mothers. Across education groups, the relative contribution of marriage to transitions declined because the prevalence of cohabitation increased. Furthermore, for children born to the low and moderately educated, marriage contributed proportionately less to transition levels over time because marital prevalence declined (by 39% and 22%), not because marriage became more stable. In contrast, for children born to the highly educated, marriage contributed proportionally fewer transitions to overall transitions because of decreased marital churning (by 34%).

Decomposition of Changes in Transitions

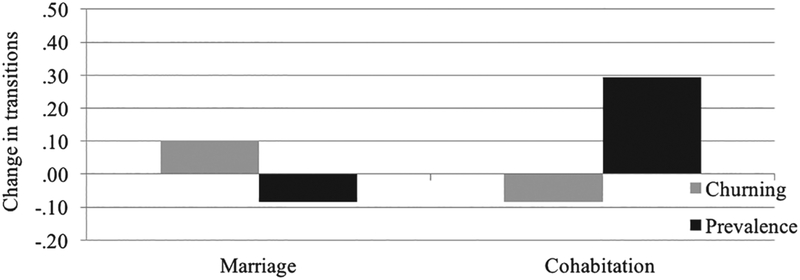

To understand how changes in transitions were driven by changes in prevalence and churning, we next present our decomposition results (Figure 1). The figure shows, for children born into each education group, how the increase in transitions observed between 1985 to 1989 and 2005 to 2010 can be decomposed into changes in prevalence (the black bars) versus changes in churning (the gray bars). The height of the bars indicates how much transitions would have changed if only that factor (e.g., prevalence or churning) had changed but the other factor was held constant. Bars above zero represent increases in transitions, and bars below zero represent decreases. For example, for children born to low-educated mothers, transitions would have increased by 0.22 if only the prevalence of relationships changed but churning remained fixed; transitions would have declined by 0.04 if only the churning of relationships changed but the prevalence remained fixed. The sum of the height of the bars represents the total change in transitions among that group.

Figure 1.

Decomposition Analysis by Maternal Education.

For children born to the low and moderately educated, changes in prevalence, rather than changes in churning, played a larger role in determining changes in transition levels. For these two groups, changes in prevalence led to 0.22 and 0.21 increases in transitions, respectively. Changes in churning had quite small effects (−0.04 and 0.02, respectively). In contrast, for children born to the most educated, changes in prevalence were completely offset by changes in churning (hence the symmetry of the bars above and below 0), explaining the null change in transitions.

The next analyses built on these findings by examining changes in prevalence and churning separately for children exposed to marriage and cohabitation (Figures 2–4). The sum of the height of all four bars represent the total change in transitions for that group.

Figure 2.

Decomposition by Maternal Relationship States, Low Educated.

Figure 4.

Decomposition by Maternal Relationship States, Highly Educated.

For children from the low and moderately educated (Figures 2 and 3), the most important component in determining the rise in transitions was changes in the prevalence of cohabitation. All else being equal, a higher prevalence of cohabitation led to an increase in transitions of 0.40 for children born to the lower educated and 0.29 for children born to the moderately educated. Changes in cohabiting churning accounted for much less of the changes in transitions in the decomposition (about −0.08) and thus did little to offset the large increase in transitions attributable to the growth in the prevalence of cohabitation.

Figure 3.

Decomposition by Maternal Relationship States, Moderately Educated.

For both groups, changes in marriage, as opposed to cohabitation, did not account for increases in transitions. For the moderately educated, changes in marriage led to virtually no increase in transitions, as changes in transitions related to the decrease in the prevalence of marriage (−0.08) was nearly offset by those related to an increase in marital churning (0.10). For the less educated, declines in marital prevalence led to a 0.18 decrease in transitions, and this far surpassed the increase in transitions from marital churning (0.04).

As denoted by the shortness of the bars in Table 4, children born to college-educated mothers, relative to the other two groups, experienced only small changes in transitions. As hypothesized, however, the null increase in the level of transitions for this group reflects the offsetting effects of decreases in churning for marriage and the increases in the prevalence of cohabitation.

In sum, across education groups, increases in the prevalence of cohabitation increased transitions. For children born to the low and moderately educated, the increase in transitions was somewhat, but not completely offset, by longer lived cohabitations and, for children born to the low educated, less exposure to marriage. Among the children born to the most advantaged, the slight increase in the prevalence of children exposed to cohabitation was completely offset by less churning among those exposed to marriage.

Supplementary Analyses

We undertook several other analyses to check the robustness of our results. We redefined our groups such that children who experienced both cohabitation and marriage were classified in the cohabiting group rather than in the married group (as was done in our main findings). The results for the most educated did not change. The results for the other two education groups changed only modestly—the change in cohabiting churning became statistically significant at p < .05 (rather than p < .10 as it is now), with no numerical increase in marital churning (vs. the nonsignificant increase seen previously). With the possible exception of marital churning for the two lower SES groups, our results were robust to different classifications for children who experienced both relationship states.

To test if demographic shifts were driving our results, we also computed results predicting transitions using regression models controlling for the mother’s race and ethnicity, mother’s age, if the mother was born to a teen mother, and the mother’s mother’s educational attainment. The results from these regressions were substantively similar to the findings presented here, suggesting that demographic changes (as observed here) did not account for our results.

We also investigated whether the increase in transitions among lower SES children differed by race and ethnicity. As noted by Brown et al. (2016), transitions increased for Black, but not for White or Hispanic children. It is possible that the increase in transitions we observed for the least educated were simply replicating these prior results by race. This was not the case; in fact, for children born to less-educated mothers, transitions increased more for White children than for Black or Hispanic children during our observed time period. The rise in transitions for White children occurred because the prevalence of cohabitation increased while cohabiting churning remained flat (i.e., cohabiting churning did not decrease, as was seen in our results for children born to the less educated). Unfortunately, small cell sizes precluded estimates of race and ethnicity by all education groups.

Finally, we reran analyses where transitions only included exits and excluded entrances. We did this analysis to examine if increases in transitions for the two less-educated groups reflected a rise in union formation. If more unions were being formed over time with biological fathers, then an increase in transitions could be beneficial for children (Lee & McLanahan, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2015). Although we could not identify biological fathers, analyses based on exits yielded similar findings as discussed previously, suggesting that it was unlikely our findings could be accounted for by an increase in biological partner unions.

Discussion

Motivated by the diverging destinies perspective (McLanahan, 2004), we analyzed the overtime trends in transitions by maternal SES and examined three issues. First, we find pronounced differences in trends in transitions by maternal education (our proxy for SES). During the past 25 years, only children from less-educated and moderately educated mothers experienced increases in family transitions; children from highly educated mothers experienced a constant (and relatively low) level of transitions.

Second, we find increasingly diverging trajectories in family transitions between children born to highly educated mothers and the other two education groups. Over time, the trend lines for the two less-advantaged groups were converging, with family contexts that were characterized by increasingly fewer marriages, an expanding incidence of cohabitations, and a relatively large and rising number of transitions. In contrast, the family contexts for children from highly educated mothers remained fairly constant, with marriage as the predominant union type and no change in the level of transitions. Because children born to more-educated mothers experienced relatively little change in their family contexts, whereas those born to less-educated and moderately educated mothers did experience change, by the end of our time period, children born to the highly educated were increasingly diverging from other children.

Third, we analyzed how much of the change in transitions was attributable to changes in prevalence and churning by maternal education. Mother’s education moderated the relative contribution of prevalence and churning. Children born to the low and moderately educated saw a rise in transitions because the prevalence of cohabitation increased; changes in the churning of marriage or cohabitation contributed little. Although cohabitations among these mothers did become slightly more stable, the increased stability of cohabitation was not occurring fast enough to offset the expanded pool of children exposed to cohabitation. In contrast, the null increase in transitions for children born to the highly educated was because modest increases in the prevalence of cohabitation was offset by modest declines in marital churning.

Our findings suggest that cohabitation, as has been suggested (Kiernan, 2001), is evolving into a family form more akin to marriage, with two notable caveats. First, although less-advantaged mothers were using cohabitation as an alternative to marriage, insofar as the prevalence of cohabitation has increased dramatically, these cohabiting unions do not begin to approach the stability of marriages. Second, for the most advantaged, we find little evidence that cohabitation is evolving to be like marriage as it remained a relatively rare union type. At least at this point in time, cohabitation is not yet indistinguishable from marriage and differs by SES.

For all children, marriage still remains much more durable than cohabitation. Even in the most recent cohort, disadvantaged children exposed to cohabitation still saw about twice as much churning as those exposed to marriage. Although cohabitation has become stickier, there are still social and legal norms that make entering and exiting marriage more difficult than cohabitation. Similar to others, we found that marriage continues to be the most durable relationship state (Brown et al., 2016; Musick & Michelmore, 2015; Rackin & Gibson-Davis, 2012).

We can only speculate as to why marriage remains a singular, stable family form that characterizes the family contexts of the most highly educated. Declining wage levels, unstable labor markets, and increasing economic uncertainty combined with the lessened stigma of nonmarital births lower the likelihood of marriage for noncollege educated individuals (Cherlin, 2014). When coupled with the specter of divorce, mothers with lower levels of education may choose less formal unions (Sassler & Miller, 2017), leading to children experiencing more transitions. College-educated women, in contrast, have much higher wages and better labor market prospects, as do their partners, which increases marriage entry (Cherlin, 2014; Sweeney, 2002). Education also increases the opportunity cost of a birth and may lead more women to delay childbearing until after marrying and establishing their careers (Isen & Stevenson, 2011).

The increasing divergence in transitions for children born to mothers with and without a college degree suggests that family transitions may be an important and increasing axis of inequality. Insofar as we found that the rise of transitions was concentrated among children born to lower SES mothers, then this group of children, but not their more advantaged peers, will be at heightened risk of the negative effects of family transitions (Cooper, Osborne, Beck, & McLanahan, 2011; Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Magnuson & Berger, 2009). Consistent with other work, we find that disadvantaged children are facing increasingly diverging destinies when compared with their more-advantaged counterparts (Amato et al., 2015; McLanahan, 2004).

Extrapolating trends in cohabiting stability into the future, however, may paint a more positive outlook for disadvantaged children. For disadvantaged children, the churning of cohabitation marginally decreased for our observed cohorts by 20% to 25%; if this trend continues, then it is possible that transitions would eventually level off or decline even if cohabiting prevalence rises. At some future point, then, cohabitation could be similar to marriage as a stable union type with two coresidential partners raising children. For this to occur, cohabitation churning would have to decrease much more rapidly than it has during the past 25 years.

Limitations to this article should be noted. First, we observed very few highly educated mothers who cohabited and could not calculate cohabitation churning among this group. Despite the small cell sizes used to calculate cohabiting prevalence among the highly educated, our results accord with other work which has found that, among this group, maternal cohabitation has increased, but remains relatively rare (Gibson-Davis & Rackin, 2014; Lundberg et al., 2016). Second, our methodological approach (e.g., combining cohabitors who marry with those who marry) precludes estimating the extent to which cohabitation has become more durable over time. Other work, however, has examined changes in cohabitation durability (Lamidi, Manning, & Brown, 2015; Musick & Michelmore, 2015). Third, our study cannot be generalized to higher order births or to children’s exposure to family transitions after the age of 5, unlike the study by Brown et al. (2016). Transitions experienced when children are older may be more likely to involve marital, rather than cohabiting, unions, and research should examine older children.

For the full sample, we found a marginally significant increase in the number of transitions, a result that seemingly contradicts Brown et al.’s (2016) previous finding that levels of transitions were plateauing. Our results cannot be directly compared to that prior study, insofar as we used a different analytic sample (first births observed until age 5, mothers up to age 34) and included more recent NSFG waves. Notably, though, if we exclude any wave past the 2006 to 2010 NSFG wave, as was done previously, then we found no substantive or significant increase in transitions.

Overall, our findings highlight the importance of taking the diverging destinies perspective into account when examining changes in the life experiences of young children. As opposed to prior work that found little change in family transitions (Brown et al., 2016), we found disquieting evidence of growing divergence in family transitions using more recent data. Prior research on all children suggested that because cohabitation had evolved to be more like marriage, transitions remained constant even as family form shifted from marriage to cohabitation. Disaggregating by socioeconomic background, however, showed that less-advantaged children face more family transitions than they were 25 years ago, but advantaged children show a pattern of constancy, leading to increasingly diverging destinies. The growing disparities in transitions likely foreshadow greater inequality in the future because the negative impacts of transitions seem to be increasingly born by disadvantaged children.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

Table A. Decomposition of Changes in Transitions between the 1985–89 and 2005–10 Cohorts, By Maternal Education

Contributor Information

Heather M. Rackin, Department of Sociology, Louisiana State University, 126 Stubbs Hall, Baton Rouge, LA 70803

Christina M. Gibson-Davis, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University, PO Box 90312, Durham, NC 27708.

References

- Amato PR, Booth A, McHale SM, & Van Hook J (2015). Families in an era of increasing inequality: Diverging destinies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AN, Cooper CE, McLanahan S, & Brooks-Gunn J (2010). Partnership transitions and maternal parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 219–233. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00695.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Stykes JB, & Manning WD (2016). Trends in children’s family instability, 1995–2010. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1173–1183. 10.1111/jomf.12311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, & Lu H-H (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies–A Journal of Demography, 54(1), 29–41. 10.1080/713779060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, & Huston AC (2006). Family instability and children’s early problem behavior. Social Forces, 85(1), 551–581. 10.1353/sof.2006.0120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, & Huston AC (2008). The timing of family instability and children’s social development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1258–1270. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00564.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2014). Labor’s love lost: The rise and fall of the working-class family in America. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, & Fine M (2000). Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1288–1307. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01288.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH Jr., Lorenz FO, Conger KJ, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, … Melby JN (1990). Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 643–656. 10.2307/352931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Osborne CA, Beck AN, & McLanahan SS (2011). Partnership instability, school readiness, and gender disparities. Sociology of Education, 84(3), 246–259. 10.1177/0038040711402361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G (1998). The life course and human behavior In Lerner R (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 939–991). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, & Cherlin AJ (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review, 72(2), 181–204. 10.1177/000312240707200203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, & Rackin HM (2014). Marriage or carriage? Trends in union context and birth type by education. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 506–519. 10.1111/jomf.12109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isen A, & Stevenson B (2011). Women’s education and family behavior: Trends in marriage, divorce and fertility In Shoven JB (Ed.), Demography and the economy (pp. 107–142). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K (2001). The rise of cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage in Western Europe. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 15, 1–21. 10.1093/lawfam/15.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamidi EO, Manning WD, & Brown SL (2015). Change in the stability of first premarital cohabitation among women in the U.S., 1983–2013 (Working Paper No. WP-2015–26). Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green Center for Family & Demographic Research; Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/center-for-familyand-demographic-research/documents/workingpapers/2015/WP-2015-26-v2-Lamidi-Changein-Stability-of-First-Premarital-Cohabitation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, & McLanahan S (2015). Family structure transitions and child development: Instability, selection, and population heterogeneity. American Sociological Review, 80(4), 738–763. 10.1177/0003122415592129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg S, Pollak RA, & Stearns J (2016). Family inequality: Diverging patterns in marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 79–102. 10.1257/jep.30.2.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K, & Berger LM (2009). Family structure states and transitions: associations with children’s well-being during middle childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 575–591. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00620.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown SL, & Stykes B (2015). Trends in births to single and cohabiting mothers, 1980–2013 (National Center for Family & Marriage Research Family Profile FP-15–03; ). Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-15-03-birth-trendssingle-cohabiting-moms.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, & Majumdar D (2004). The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23(2), 135–159. 10.1023/B:POPU.0000019916.29156.a7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mare RD (2016). Educational homogamy in two gilded ages: Evidence from inter-generational social mobility data. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 663, 117–139. 10.1177/0002716215596967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP (2006). Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research, 15, 537–560. 10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the Second Demographic Transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627. 10.1353/dem.2004.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO, McLanahan SS, & Brooks-Gunn J (2008). Stability and change in family structure and maternal health trajectories. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 314–334. 10.1177/000312240807300207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C, McLanahan S, Notterman D, Hobcraft J, Brooks-Gunn J, & Garfinkel I (2015). Family structure instability, genetic sensitivity, and child well-being. American Journal of Sociology, 120(4), 1195–1225. 10.1086/680681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, & Michelmore K (2015). Change in the stability of marital and cohabiting unions following the birth of a child. Demography, 52(5), 1463–1585. 10.1007/s13524-0150425-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Survey of Family Growth. (2015). About the National Survey of Family Growth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/about_nsfg.htm

- Osborne C (2005). Marriage following the birth of a child among cohabiting and visiting parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 14–26. 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00002.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, Manning WD, & Smock PJ (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1345–1366. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00451.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, & McLanahan S (2007). Partnership instability and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA, & Shonkoff JP (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackin HM, & Gibson-Davis CM (2012). The role of pre-and postconception relationships for first-time parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 526–539. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00974.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, & Wildsmith E (2004). Cohabitation and children’s family instability. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 210–219. 10.2307/3599876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Palmore JA, & Bumpass LL (1982). Selectivity and the analysis of birth intervals from survey data. Asian and Pacific Census Forum, 8(3), 5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Claessens A (2013). Associations between family structure changes and children’s behavior problems: The moderating effects of timing and marital birth. Developmental Psychology, 49(7), 1219 10.1037/a0029397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, & Miller A (2017). Cohabitation nation: Gender, class, and the remaking of relationships. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67(1), 132–147. 10.2307/3088937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, & Thomson E (2001). Race differences in family experience and early sexual initiation: Dynamic models of family structure and family change. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 682–696. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00682.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.