Abstract

We examined longitudinal change in language expression during a semi-structured speech sample in 48 patients with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) or behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and related this to longitudinal neuroimaging of cortical thickness available in 25 of these patients. All patient groups declined significantly on measures of both speech fluency and grammar, although patients with nonfluent/agrammatic PPA (naPPA) declined to a greater extent than patients with the semantic variant, the logopenic variant, and bvFTD. These patient groups also declined on several neuropsychological measures, but there was no correlation between decline in speech expression and decline in neuropsychological performance. Longitudinal decline in grammaticality, assessed by the number of well-formed sentences produced, was associated with longitudinal progression of gray matter atrophy in left frontal operculum/insula and bilateral temporal cortex.

Keywords: primary progressive aphasia, frontotemporal dementia, language, speech, longitudinal

1. INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) is a neurodegenerative condition with insidious onset and gradual, inexorable decline. Several variants are recognized by international consensus criteria. Two of these are forms of primary progressive aphasia (PPA), often associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) spectrum pathology (Grossman, 2010), including the nonfluent/agrammatic variant (naPPA) and the semantic variant (svPPA) (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). A third type of PPA is the logopenic variant (lvPPA), which is associated with Alzheimer’s pathology in the majority of cases (Giannini et al., 2017; Rohrer et al., 2010). While these conditions are recognized for their prominent language disorder, the behavioral variant of FTD (bvFTD) (Rascovsky et al., 2011) may be associated with some language difficulties as well (Grossman, 2018). The deficits in language production and comprehension in these syndromes are the subject of intense study, but investigations of change over time in these patients in different aspects of cognitive functioning, including language, are rare. An improved understanding of the evolution of language capabilities overtime in these conditions could potentially contribute to the focus of speech therapy interventions, facilitate accurate diagnosis, increase accuracy of prognosis, and improve endpoints in treatment trials. The present paper reports a longitudinal study of the decline in language production and concomitant neuroanatomical changes in the PPAs and bvFTD. The object of this work is to identify differences in their patterns of change over time by focusing on natural speech production.

naPPA is characterized by slowed, effortful speech with speech sound errors, agrammatism in language production, and impaired comprehension of grammar, with cortical atrophy in premotor, inferior frontal, anterior insula, and anterior-superior temporal regions of the left hemisphere (Bergeron et al., 2018; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Grossman et al., 2013; M. M. Mesulam et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2010). svPPA is distinguished by declining confrontation naming, word comprehension difficulty, and impaired object knowledge, with anterior temporal lobe atrophy that is more prominent on the left than the right (Bonner, Ash, & Grossman, 2010; Cousins, Ash, Irwin, & Grossman, 2017; Cousins, Ash, Olm, & Grossman, 2018; Cousins, York, Bauer, & Grossman, 2016; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Hodges & Patterson, 2007). lvPPA presents with impaired repetition, word-finding pauses, and phonologic errors, with predominantly left hemisphere temporal-parietal atrophy (Giannini et al., 2017; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2010). Individuals with bvFTD are most notable for a progressive decline in social conduct, including disinhibition, apathy, loss of empathy, loss of insight, and executive dysfunction, associated with frontal and temporal atrophy (Rascovsky et al., 2011). While they are not obviously aphasic, their speech exhibits poor organization of discourse, grammatical simplification, selective impairments in word use, and changes in acoustic properties (Ash et al., 2006; Cousins & Grossman, 2017; Healey et al., 2015; Nevler et al., 2017).

There are numerous cross-sectional studies of language deficits in the variants of PPA (Ash et al., 2009; Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Grossman, 2010; M.-M. Mesulam et al., 2009; Weintraub, Rubin, & Mesulam, 1990; Wilson et al., 2010), but longitudinal studies of change in these patients are rare. Those longitudinal studies that have been reported span a range of methods and findings. One early longitudinal study of individuals with PPA conducted by Thompson et al. (1997) compared 4 PPA patients (of unspecified variants) to agrammatic Broca’s aphasic patients and controls in a detailed analysis of connected speech production. The authors found discrepant patterns of language decline, whereby 3 PPA patients exhibited progressive impairment in grammatical production while 1 had increasing word retrieval deficits with intact grammar. A longitudinal study of change in comprehension of grammatically complex and simple sentences in naPPA and svPPA (Grossman & Moore, 2005) found that naPPA patients were significantly impaired at first presentation in the comprehension of grammatically complex sentences, which correlated with a deficit in verbal working memory. The comprehension deficit was severe at first presentation and did not show significant change over time. In contrast, svPPA patients who exhibited a semantic memory deficit at first presentation declined significantly in the comprehension of complex sentences, suggesting that a deficit in single word comprehension contributed to that progressive impairment. In another longitudinal study of patients with semantic dementia (svPPA), Bright et al. (2008) investigated whether the core impairments in this syndrome affected semantics only or whether they also involved other language areas, using annual MRI scans of 2 patients in conjunction with language testing. They found variability in the pattern and rate of atrophy progression over time, but found atrophy first in ventral temporal cortex in regions related to object processing and semantic memory. The authors concluded that the early stages of the condition were characterized by a semantic deficit and that a generalized language impairment developed with disease progression, when damage spread to perisylvian language areas. With regard to lvPPA, one longitudinal study that focused on brain imaging found a decline in brain volume over time accompanied by increasing deficits in language features characteristic of this syndrome, including naming, sentence repetition, and sentence comprehension (Rohrer et al., 2013). The authors also found deficits in recognition memory and single word repetition and comprehension consistent with spreading atrophy as the disease progressed. Another study of lvPPA (Etcheverry et al., 2012) documented decline in 3 patients tested at 6-month intervals over 18 months for a global measure of aphasia, story retelling, speech motor functioning, and verbal fluency. The authors observed decline in both verbal and non-verbal skills, with notable individual variability in disease progression. Tree & Kay (2015) conducted a longitudinal study of 1 individual with lvPPA over a period of 2 years, with a focus on the decline of phonological short-term memory. They observed a progressive reduction in digit span, declining performance on both word and non-word repetition, and emergence of an impairment in homophone judgment. In addition, they found a decline in single word comprehension and severe deficits in picture naming, which declined further over the course of the study. Tu et al. (2016) conducted a longitudinal study of change in language function and white matter in svPPA and lvPPA over a 1-year period. They found that lvPPA declined on naming and repetition, while svPPA declined on naming and comprehension. White matter tract changes differed between the two groups. lvPPA showed degradation predominantly in the left uncinate fasciculus (UF), inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), and temporal portion of the superior longitudinal fasciculus, with a lesser degree of degradation in the same regions of the right hemisphere. svPPA exhibited a more focal pattern of progressive degradation, involving primarily the left UF and anterior portion of the ILF. In a study of the 3 variants of PP A, Faria et al. (2014) examined the correlation of change in auditory word comprehension with cortical atrophy. At initial testing, they found that auditory word comprehension was correlated with atrophy in bilateral temporal pole, bilateral inferior temporal cortex, and left middle temporal cortex, areas associated with svPPA. Change in word comprehension correlated with change in cortical volume of bilateral middle temporal and right inferior temporal regions and angular gyrus. They conclude by suggesting that areas such as middle temporal cortex and angular gyrus may play a role in compensating for auditory comprehension deficits. Another study of the 3 variants of PPA that focused on cortical atrophy included neuropsychological and language testing at 2 time points with a 2-year interval (Rogalski et al., 2014). The investigators found decline in performance on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) (Kertesz, 1982) in all three groups, with naPPA scoring significantly lower than lvPPA at follow-up testing, and cortical decline greater in the left hemisphere than the right. A further recent longitudinal study of the 3 variants of PPA examined gray and white matter atrophy and changes in cognition and language with a 1-year follow-up from baseline (Brambati et al., 2015). These authors found differing patterns of atrophy progression in the 3 groups, which corresponded to the different patterns of cognitive and language decline.

All of these studies have yielded important findings. With some exceptions, they focus mainly on elicited forms, through tasks such as naming and repetition, or on comprehension of words or sentences. The present study, like the early study of Thompson et al. (1997), examines speech production in a task that elicits spontaneous connected speech, as an approximation to the everyday conversational speech of individuals interacting with the world around them. We evaluated semi-structured speech samples using a picture description task in 4 groups of patients, and we compared features of fluency and grammar at 2 time points for each patient. The picture description task has the advantage of allowing the speaker free rein to demonstrate the range of his or her linguistic capabilities while the intended target of the narrative is known. We found that specific features of language performance declined over time, including features of both speech fluency and grammatical expression. We also observed individual variability, as have previous investigators. We used structural MRI analysis to relate change in cortical thickness (CT) at baseline and longitudinal follow-up to decline on measures of speech production. We found that specific features of language performance declined overtime, including speech fluency and grammatical expression. Deterioration in language performance longitudinally was related to concurrent gray matter loss in brain regions important for language.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

We conducted a longitudinal study of 48 patients with PPA or bvFTD and 36 healthy demographically matched controls. The patient groups included naPPA (n=9), svPPA (n=11), lvPP A (n=14), and bvFTD (n=14). Patients were recruited in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania and diagnosed by experienced neurologists (MG, DJI) according to published criteria (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Rascovsky et al., 2011). Criteria for lvPPA were modified in accordance with a recent clinical-pathological study (Giannini et al., 2017) to include a repetition deficit defined by <4 digits forward on a span task. None of the bvFTD patients met criteria for a PPA syndrome. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. Patients with other causes of dementia, such as metabolic, endocrine, vascular, structural, nutritional, and infectious etiologies or primary psychiatric disorders, were excluded. The four patient subgroups did not differ from each other in disease duration, neither at the time of first testing (Time 1), nor at the time of follow-up testing (Time 2), nor on the duration of the interval between Time 1 and Time 2. All groups were matched for age, sex, and education, and the four patient groups did not differ on MMSE at Time 1. At Time 2, svPP A patients had a significantly lower MMSE than lvPPA patients (p=.025) and bvFTD patients (p<01). All subjects completed an informed consent procedure in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and controls: Mean (SD)

| naPPA | svPPA | lvPPA | bvFTD | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/F | 2/7 | 7/4 | 7/7 | 9/5 | 13/23 |

| Education (y) | 13.9 (1.9) | 15.2 (3.0) | 16.0 (3.4) | 16.3 (3.0) | 15.9 (2.5) |

| Age at Time 1 | 66.1 (9.0) | 61.0 (8.1) | 64.9 (7.8) | 67.1 (9.9) | 69.1 (7.7) |

| Age at Time 2 | 67.5 (9.3) | 63.9 (9.1) | 67.0 (7.8) | 69.4 (10.2) | -- |

| Time 1-Time 2 interval (months) | 16.9 (7.2) | 34.7 (26.2) | 25.3 (14.1) | 27.2 (19.3) | -- |

| Disease duration at Time 1 (y) | 2.3 (0.7) | 3.4 (2.0) | 3.6 (2.3) | 4.1 (3.1) | — |

| Disease duration at Time 2 (y) | 3.8 (0.8) | 6.3 (2.2) | 5.7 (3.0) | 6.5 (2.7) | — |

| MMSE, Time 1 | 23.6 (6.2)* | 25.0 (3.2)* | 25.3 (4.2)* | 26.7 (2.6)* | 29.1 (1.1) |

| MMSE, Time 2 | 18.7 (9.3)*# | 15.8 (6.0)*#^ | 20.5 (7.3)*# | 24.9 (4.1)*# |

Notes:

* Differs from Controls, p<.01

# Differs from corresponding Time 1, p<.05

^ svPPA differs from lvPPA (p<.05) and from bvFTD (p<.01)

2.2. Procedure

We performed two assessments of each patient, at Time 1 and Time 2, with an interval of at least 12 months (mean ± SD = 26.4 ± 18.6 months). Controls were recorded only once, since assessing change over time in this group was not the object of the study and the rate of change in healthy controls is too slow to be captured. Participants were instructed to describe the Cookie Theft scene from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1972). The picture is a black-and-white line drawing which shows a boy and a girl taking cookies from a cookie jar in a cabinet, with the boy standing on a stool that is tipping over. Their mother is washing dishes at the kitchen sink, with her back to the children. The sink is overflowing and water is spilling onto the floor, forming a pool of water under the mother’s feet. The mother takes no notice of either the water or the children’s actions. There is a window over the kitchen sink through which an outdoor scene is visible.

Participants were asked to describe the scene in as much detail as possible. Prompts were offered after a silence of a few seconds, if necessary, to elicit a speech sample of approximately 60 sec, including silences (mean ± SD = 78 ± 29 sec). The speech samples were recorded digitally as described elsewhere (Ash et al., 2013).

2.3. Speech analysis

The speech samples were transcribed by trained transcribers using the signal processing program Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 1992-2014). All transcriptions were reviewed by an experienced linguist (S A). The speech samples were analyzed for features of fluency and grammatical structure. Fluency was measured in terms of two of its components, speech rate and frequency of speech errors, since both of these contribute to the smooth flow of speech production. Speech rate was assessed as the number of complete words spoken per minute (WPM). Speech errors consisted of uncorrected sequences of phonemes or non-phonemic segments that did not constitute a word or partial word. Following Knibb et al. (2009), we did not distinguish between errors of apraxia (distortions) and errors of phonemic substitution. Those authors grouped together errors of apraxia of speech (AOS), dysarthria, and phonemic substitution, on the grounds that “a distortion maybe either dysarthric or apraxic, and a substitution may be either phonemic or a gross articulatory error.” In the present study, we were concerned with speech errors as interruptions of the flow of speech, without regard to whether they were the consequence of an impairment of motor planning or phonological encoding.

Grammatical structure was assessed in terms of frequency of dependent clauses and percentage of utterances that were well-formed sentences. An utterance was defined as an independent clause and all clauses dependent on it (Hunt, 1965). A dependent clause was defined as a clause containing a subject and a verb phrase but one that cannot stand on its own. The frequency of dependent clauses is a measure of grammatical complexity, measuring the frequency of embedded structures in a sentence. For purposes of analysis, the number of dependent clauses per 100 utterances was evaluated. Utterances that counted as well-formed sentences were sentences that were free of grammatical errors, regardless of the truth value of the content that was expressed. The judgment of well-formedness was made after false starts and other extraneous material had been excluded. In what follows, this variable will be referred to simply as “well-formed sentences.”

2.4. Statistical considerations

Statistical analyses of language variables were conducted using SPSS v.25. To evaluate and compare the rate of change in performance on the language variables, we compared groups by conducting a repeated measures ANOVA of performance on the 4 language variables at Times 1 and 2, with patient group as a between-subjects variable. For speech errors per 100 words, only naPPA and lvPPA were analyzed, since the other two groups had too few speech errors for statistical analysis. We also calculated the z-scores of individual patients relative to the mean performance by controls for each variable. The language variables were selected to represent aspects of fluency and grammar that are not (or are minimally) collinear. However, features of speech production may interact. For example, silences within the stream of speech reduce the number of words spoken in a given amount of time, so these features are closely tied to each other. To assess the interdependence of the speech variables selected for this study, we calculated correlations of the measures of fluency and grammar at Time 1 and Time 2 for each patient group.

Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances indicated that some language measures did not meet the requirement of homogeneity for parametric statistical tests. Therefore we used nonparametric tests to assess these differences between and within subject groups. Pairwise comparisons between subject groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U statistic, and comparisons within subject groups were calculated using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Correlations between measures of change in performance on language measures and neuropsychological measures were evaluated using Spearman’s rho. Unless otherwise stated, all differences are significant at least at the two-tailed level p<.05.

2.5. Imaging methods

Structural MRI scans were available for 25 patients (4 naPPA, 6 svPPA, 8 lvPPA, 7 bvFTD) within 1 year of the first Cookie Theft recording (mean ± SD interval = 67 ± 84 days) and within 1 year of the second Cookie Theft recording (mean ± SD interval = 98 ±98 days). Forty-one (82%) of the scans used in the analysis were made within 6 months of the corresponding Cookie Theft recording. Because of the small numbers of patients in each group, we aggregated all patients into a single cohort. We also examined 18 demographically matched healthy seniors. The patients with baseline MRI scans did not differ statistically from the full cohort of their respective subgroups on any demographic or language measure (see Supplementary Table S-l).

Briefly, participants underwent a structural T1-weighted MPRAGE MRI acquired from a SIEMENS 3.0 Tesla Trio scanner with an eight-channel coil using the following parameters: repetition time (TR)=1,620 ms; echo time (TE)=3 ms; 160 1.0 mm slices; flip angle=15°; matrix=192 ×256; and inplane resolution=0.9766 mm × 0.9766 mm. T1 MRI images were preprocessed using antsCorticalThickness (Tustison et al., 2014). Each individual dataset was deformed into a standard local template space in a canonical stereotactic coordinate system. Registration was performed using a diffeomorphic deformation that is symmetric to minimize bias toward the reference space for computing the mappings and topology-preserving to capture the large deformation necessary to aggregate images in a common space. The ANTs Atropos tool used template-based priors to segment images into 6 tissue classes (cortical gray matter, white matter, CSF, deep gray structures, brainstem, and cerebellum) and generated the probability images of each tissue class (Avants, Tustison, Wu, Cook, & Gee, 2011). Here we focused on cortical gray matter thickness (CT) images that were downsampled to 2mm isotropic voxels and smoothed using a 4 mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian kernel before analysis to analyze a small and biologically reasonable voxel dimensionality that approximates CT.

To estimate patients’ overall atrophy patterns, we compared voxelwise cortical thickness inpatients and controls at both initial and follow-up scans using ANTsR (http://stnava.github.io/ANTsR/). To perform multiple comparisons adjustment, we thresholded statistical maps at an uncorrected voxelwise threshold of p<001, then used the AFNI 3dFWHMx and 3dClustSim functions to determine a minimum cluster volume that corresponded to a cluster-wise corrected significance of p<05, independent of spatial auto-correlation (Cox, Chen, Glen, Reynolds, & Taylor, 2017; Forman et al., 1995). This procedure yielded a minimum cluster volume of 87 voxels (696 μl) for atrophy results at Time 1 and 91 voxels (728 μl) for Time 2. Associations between cognitive change and longitudinal cortical thinning were analyzed using linear mixed effects (LME) models with the 3dLME function (Chen, Saad, Britton, Pine, & Cox, 2013) from AFNI (https://afni.nimh.nih.gov). Separate LME models were calculated for each of the four speech outcomes of interest: WPM, well-formed sentences, dependent clauses per 100 utterances, and speech errors per 100 words. Each model included a random effect of participant and fixed effects of language performance at the initial scan, change in performance at follow-up, and the time interval in years between each language observation and the corresponding MRI scan. LME analysis was restricted to gray matter voxels. The main outcome of interest was the t-statistic map indicating associations between change on each measure and longitudinal cortical thickness. As with atrophy contrasts, results were thresholded at voxelwise p<0.001, and a cluster threshold of 125 voxels (1000 μl) was applied to yield a cluster-wise corrected significance of p<0.05. Since all groups were matched for demographic variables, we did not covary for age or disease duration. Imaging results are displayed in standard local template space.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Comparison of groups at Time 1 (baseline)

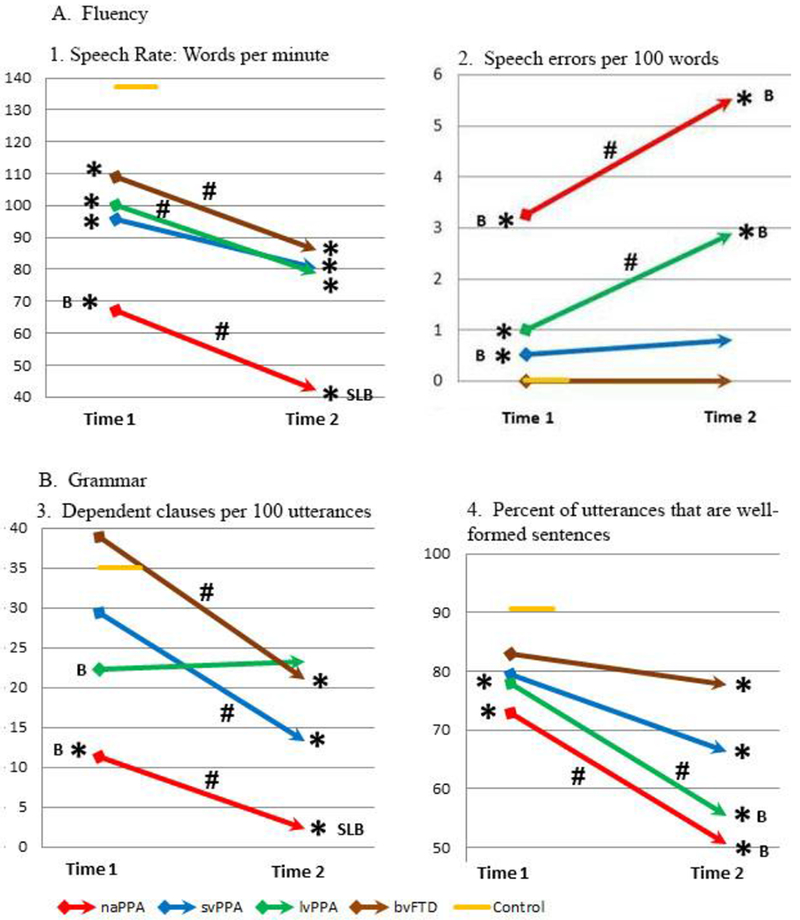

Comparisons of the patient groups with controls and with each other on WPM, speech errors, dependent clauses, and well-formed sentences are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean measures of fluency and grammar in PPA and bvFTD at Times 1 and 2

Notes:

# within-group change, p<.05

* differs from controls, p<.05

S differs from svPPA, p<.05; L differs from lvPPA, p<.05; B differs from bvFTD, p<.05

Assessments of fluency at baseline indicated that individuals with naPPA were impaired relative to controls on both WPM and speech error measures. In addition, their performance on WPM and speech errors was worse than that of bvFTD patients. svPPA patients were also impaired relative to controls on WPM and speech errors, and they were impaired relative to bvFTD on speech errors at baseline. lvPPA patients were impaired relative to controls on WPM and speech errors. bvFTD patients also exhibited reduced WPM at baseline compared to controls, but they produced few speech errors.

Patients with naPPA were impaired at baseline relative to controls on the two measures of grammar, namely, production of dependent clauses as a percentage of utterances and percentage of utterances that were well-formed sentences. lvPPA patients were impaired relative to controls in the production of well-formed sentences. naPPA and lvPPA patients were also impaired relative to bvFTD on dependent clause production. svPPA and bvFTD patients were not impaired on either of the measures of grammatical production at Time 1.

3.2. Comparison of groups at Time 2

All patient groups were impaired relative to controls on speech rate at Time 2, as they were at Time 1. In addition, naPPA patients were impaired relative to svPPA and lvPPA, as well as relative to bvFTD. For speech errors, naPPA and lvPPA were impaired relative to controls and bvFTD at Time 2.

Regarding measures of grammar, naPPA were impaired on dependent clause production relative to all other patient groups as well as controls at Time 2, and svPPA and bvFTD were also impaired relative to controls. All 4 patient groups were impaired compared to controls in the production of well-formed sentences at Time 2, and naPPA and lvPPA were additionally impaired relative to bvFTD.

3.3. Correlations among language variables

The correlations found between WPM and the remaining language variables for the 3 PPA groups are presented in Table 2. As shown, at Time 1, there were no significant correlations of speech variables with each other in naPPA. At Time 2, speech rate was correlated with the frequency of dependent clauses and well-formed sentences, and these two grammatical features were correlated with each other. In svPPA, there was a significant correlation of WPM with frequency of dependent clauses and percentage of well-formed sentences at Time 1, but only the correlation of speech rate with well-formed sentences carried over to Time 2. In lvPPA, at Time 1, speech rate was correlated with well-formed sentences and speech errors were correlated with dependent clauses, but at Time 2, all the speech production variables were correlated with each other except for dependent clauses and well-formed sentences. bvFTD patients exhibited no significant correlations among the language measures at Time 1 or Time 2.

Table 2.

Within-group correlations (rs) of speech variables at Times 1 and 2

| naPPA | svPPA | lvPPA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 1 | Time 2 | |

| Correlations of speech rate (WPM) with other speech variables | ||||||

| Speech errors/100 words | −.32 ns | −.55 ns | −.16 ns | .27 ns | −.10 ns | −.71** |

| Dependent clauses/100 utterances | .38 ns | .71* | .82** | .47 ns | .34 ns | .70** |

| % Well-formed sentences | .38 ns | .75* | .88*** | .92*** | .56* | .54* |

| Correlations of Speech errors with other speech variables | ||||||

| Dependent clauses/100 utterances | −.27 ns | −.30 ns | −.33 ns | −.03 ns | .60* | −.61* |

| % Well-formed sentences | −.26 ns | −.04 ns | −.11 ns | .26 ns | −.52 ns | −.83*** |

| Correlations of Dependent clauses /100 utterances with other speech variables | ||||||

| % Well-formed sentences | .06 ns | .71* | .56 ns | .53 ns | −.20 ns | .46 ns |

Notes:

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

ns = not significant, p>.12

3.4. Within- and between-group change from Time 1 to Time 2

Significant within-group change is displayed in Figure 1. naPPA patients became significantly more impaired over time on both measures of fluency, WPM and speech errors. Individual naPPA patients declined on WPM and speech errors by a z-score >1 in their fluency performance in 33% and 56% of individuals, respectively. lvPPA patients also declined significantly on both WPM and speech errors, with a decrease in z-score >1 in 36% and 50% of individual lvPPA patients respectively. svPPA patients did not decline significantly on either measure as a group, although 36% of individual svPPA patients had a decline in z-score>1 on both WPM and speech errors. bvFTD patients declined significantly on WPM but not speech errors, with a decline in z-score >1 in 36% and 7% of patients, respectively.

Regarding grammatical features, naPPA patients declined significantly in the production of dependent clauses and well-formed sentences from Time 1 to Time 2. Individual naPPA patients declined on dependent clauses and well-formed sentences by a z-score >1 in 22% and 67% of individuals, respectively. svPPA and bvFTD patients declined significantly in the production of dependent clauses, but not on well-formed sentences. Individual svPPA patients exhibited a decline in z-score>l on dependent clauses and well-formed sentences in 36% and 27% of cases, respectively, while individual bvFTD patients declined by a change in z-score>l in 50% and 36% of cases, respectively. lvPPA patients declined significantly in the production of well-formed sentences but not dependent clauses. Individual lvPP A patients showed a decline on dependent clauses and well-formed sentences with a change in z-score>l in 7% and 71% of cases, respectively.

3.5. Comparisons of Time 1 and Time 2 across groups

Details of the repeated measures ANOVA for the 4 speech variables are presented in Table 3. For speech rate (WPM), the repeated measures ANOVA revealed that the main effect for Time was significant; thus, WPM at Time 2 was significantly different from WPM at Time 1 overall. A significant main effect for Group was obtained, indicating that there was a difference in the WPM scores among groups. The interaction of Time × Group was not significant. Therefore, we observe an overall significant decline in WPM from Time 1 to Time 2, but that decline does not differ significantly among groups. This decline in speech rate is illustrated in Figure 1A1, as described above.

Table 3.

Main effects for Time, Group, and Time × Group interaction for speech performance at Times 1 and 2 for naPPA, svPPA, lvPPA, and bvFTD.

| F | p | eta squared | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WPM | |||

| Time | F(1,44)=26.87 | <.001 | .379 |

| Group | F(3,44)=2.85 | .048 | .163 |

| Time × Group | F(3,44)=.233 | .873 | .016 |

| Speech errors/100 words | |||

| Time | F(1,21)=11.58 | .003 | .355 |

| Group | F(1,21)=2.45 | .133 | .104 |

| Time × Group | F(1,21)=0.093 | .763 | .004 |

| Dependent clauses/100 utterances | |||

| Time | F(1,44)=13.15 | .001 | .230 |

| Group | F(3,44)=3.76 | .017 | .204 |

| Time × Group | F(3,44)=2.59 | .065 | .150 |

| % Well-formed sentences | |||

| Time | F(1,44)=14.06 | .001 | .242 |

| Group | F(3,44)=1.47 | .132 | .119 |

| Time × Group | F(3,44)=1.07 | .372 | .068 |

For speech errors per 100 words, including only naPPA and lvPPA, the repeated measures ANOVA indicated that the main effect for Time was significant, but there was not a significant main effect for Group or for the interaction of Time × Group. Thus, the increase in speech errors over time was significant for these patients overall, but the two groups did not differ in the pattern of increasing impairment; this is displayed in Figure 1A2.

For dependent clauses per 100 utterances, the repeated measures ANOVA revealed that the main effect for Time was significant, and a significant main effect for Group was also obtained. The interaction of Time × Group was not significant. Thus the trajectory of decline in dependent clause production was not significantly different among groups. This is illustrated in Figure 1B3.

For percentage of well-formed sentences, the repeated measures ANOVA indicated that the main effect for Time was significant. There was not a significant main effect for Group, and the interaction of Time × Group also was also not significant. Thus, the longitudinal decline of well-formed sentence production was significant overall, and the 4 patient groups declined similarly. This is illustrated in Figure 1B4.

3.6. Neuropsychological measures

We examined longitudinal change on neuropsychological measures, as reported in Table 4. To assess the contribution of cognitive decline to advancing impairments in language functioning, we evaluated the change in cognitive status for each patient group. We considered the overall change in cognitive status by recording change on the MMSE. We assessed change in lexical access as represented by the Boston Naming Test (BNT); short-term auditory memory as represented by forward digit span (FDS); working memory as tested by reverse digit span (RDS); semantically guided search as number of animals named in one minute; and letter-guided search for the letters F, A, and S. naPPA and bvFTD patients did not decline significantly on any of the neuropsychological measures except the MMSE. svPPA patients declined on the BNT and two measures of executive functioning, reverse digit span and letter-guided fluency (FAS); and lvPPA patients declined on the BNT and category-guided fluency (animal naming).

Table 4.

Cognitive characteristics of patients and controls: Mean (SD)

| naPPA | svPPA | lvPPA | bvFTD | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive measures | |||||

| MMSE, Time 1 | 23.6 (6.2)* | 25.0 (3.2)* | 25.3 (4.2)* | 26.7 (2.6)* | 29.1 (1.1) |

| MMSE, Time 2 | 18.7 (9.3)*# | 15.8 (6.0)*# | 20.5 (7.3)*# | 24.9 (4.1)*# | |

| BNT, Time 1 | 25.0 [1] | 6.4 (4.8) [8]* | 21.2 (8.7) [12]* | 23.0 (6.4) [10]* | 27.9 (2.5) [1] |

| BNT, Time 2 | 12.0 (15.6) [2]* | 5.1(8.5) [7]*# | 17.1 (10.0) [11]*# | 20.1 (8.0) [11]* | |

| FDS, Time 1 | 43 (1.6) [6]* | 5.6 (2.0) | 4.1 (4.4)* | 7.0 (1.1) [11] | 7.2 (1.1) [17] |

| FDS, Time 2 | 3.9 (1.7) [8]* | 4.2 (2.6) [9]* | 3.7 (1.8) [13]* | 6.8 (1.0) [12] | |

| RDS, Time 1 | 2.3 (1.4) [6]* | 4.0 (1.5)* | 3.3 (0.8)* | 4.7 (0.8) [11] | 5.7 (1.4) [18] |

| RDS, Time 2 | 2.2 (1.2) [8]* | 2.2 (1.6) [9]*# | 2.6 (1.4) [13]* | 4.2 (1.3) [12]* | |

| Animal naming, Time 1 | 7.0 (0.0) [2]* | 7.9 (4.4) [8]* | 11.7 (4.8) [13]* | 11.8 (5.1) [11]* | 19.2 (5.7) [23] |

| Animal naming, Time 2 | 6.0 (2.6) [3]* | 3.9 (4.7) [7]* | 8.1 (5.5) [12]*# | 8.4 (4.6) [11]* | |

| FAS, Time 1 | 17.2 (10.0) [5]* | 24.0 (11.0) [10]* | 21.7 (12.7) [12]* | 29.0 (13.2) [11]* | 41.8 (10.6) [23] |

| FAS, Time 2 | 11.8 (9.4) [4]* | 11.58 (9.4) [8]*# | 17.2 (12.0) [12]* | 23.0 (13.2) [13]* | |

Notes:

differs from Controls, p<.01

differs from corresponding Time 1, p<.05

Numbers of participants for whom scores were available are given in brackets if less than the total; BNT = Boston Naming Test; FDS = Forward Digit Span; RDS = Reverse Digit Span; FAS = letter-guided fluency for F, A, S

To assess the correspondence of a decline in cognitive function to a decline in language performance, we examined correlations between change in cognitive measures and change in measures of language performance. For naPPA, although these individuals declined on all measures of language performance, there was no correlation of change in any language variable with change in MMSE (all p>.4), the only cognitive feature on which these participants exhibited significant decline. For svPPA, the only language performance measure that exhibited decline was dependent clause production, and this measure did not correlate with change in any of the neuropsychological measures (all p>.3). lvPPA patients declined significantly on speech rate, speech errors, and well-formed sentences, but change in these measures did not correlate with decline on any of the neuropsychological measures (all p>. 13). Finally, bvFTD patients declined only on speech rate and dependent clause production, but this change did not correlate with decline on the MMSE. As noted above, this is the only cognitive measure for which bvFTD showed significant change (all p>.25). In sum, there was little correlation between decline in speech measures and decline on neuropsychological measures.

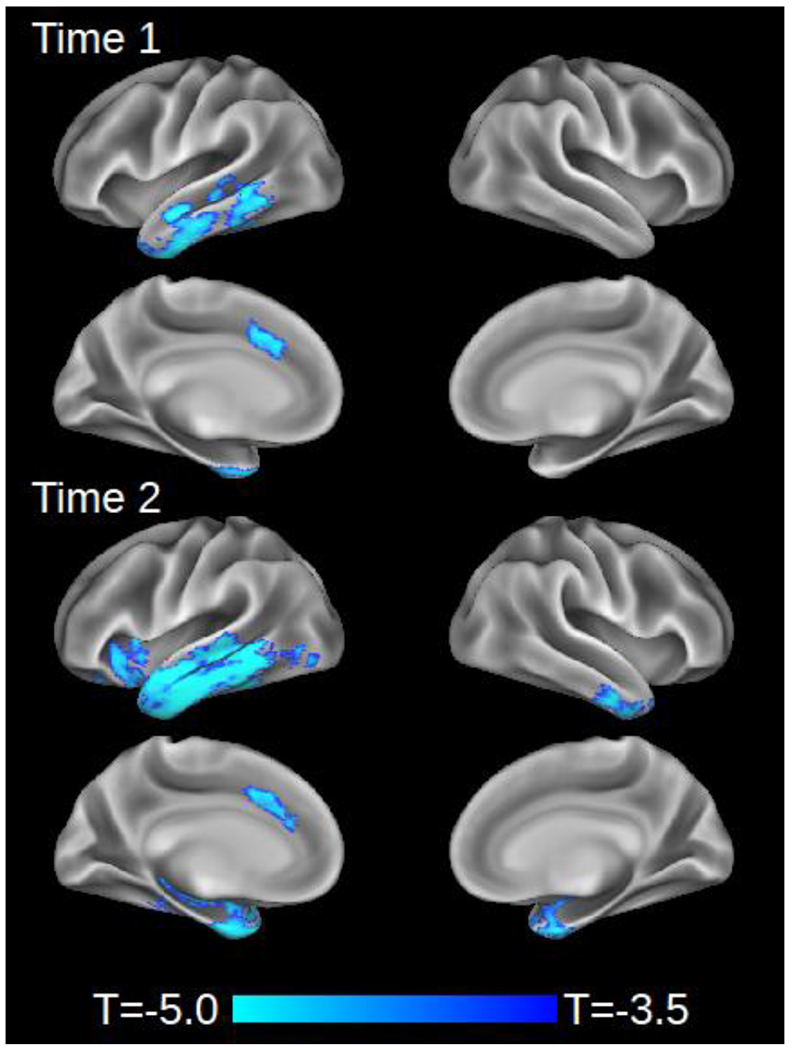

3.7. Imaging

Areas of significant cortical thinning relative to control participants are illustrated in Figure 2, and peak coordinates are reported in supplementary data (Tables S-2 and S-3). At Time 1, atrophy was restricted to the left lateral temporal lobe and middle cingulate gyrus. At Time 2, patients exhibited evidence of atrophy progression throughout left lateral temporal cortex, extending posteriorly to the inferior occipital gyrus and anteriorly to encompass the posterior and middle orbital gyrus in the frontal lobe. New atrophy at Time 2 also encompassed left frontal operculum/anterior insula, posterior insula, entorhinal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus. Finally, new atrophy was observed in the right inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, entorhinal cortex, temporal pole, and amygdala.

Figure 2.

Cortical atrophy in combined cohort of naPPA, svPPA, lvPPA, and bvFTD (N=25) relative to matched controls (n=18) at initial scan (Time 1) and follow-up (Time 2).

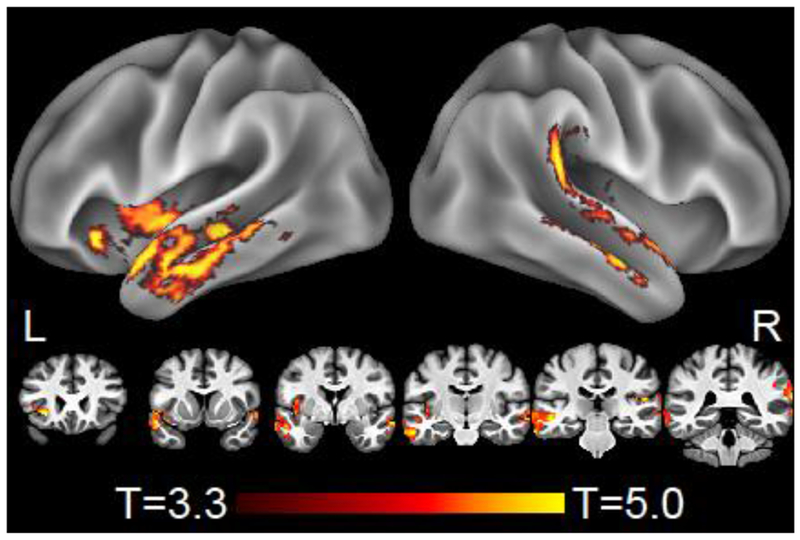

We additionally used LME models to identify areas where change in speech production measures from Time 1 to Time 2 was associated with concurrent change in CT. After correction for multiple comparisons, decline in production of well-formed sentences was associated with cortical thinning in left frontal operculum/anterior insula; left middle/posterior insula; left inferior temporal gyrus; bilateral superior/middle temporal cortex; and right posterior temporal and opercular cortex (Figure 3, Table S-4). However, no significant associations with cortical thinning were found for change in WPM, dependent clauses per 100 utterances, or speech errors per 100 words.

Figure 3.

Whole-brain regression of longitudinal change in grammaticality (well-formed sentences produced) with longitudinal change in atrophy. Results are thresholded at voxelwise p<.001 with a minimum cluster size of 125 voxels, corresponding to cluster-wise corrected p<.05. Results are displayed on a local template brain; stereotactic coordinates of peak effects are given in MNI space in Table S-4.

4. DISCUSSION

We conducted a longitudinal study of 48 patients with PPA or bvFTD to identify patterns of decline in the production of connected speech and language. We found relatively prominent decline in speech fluency and grammaticality inpatients with naPPA, and we observed somewhat similar patterns of progressive speech impairment in the other patient groups as well. Progressive impairments in grammaticality were related to change in temporal and frontal areas that are frequently compromised in PPA. We will consider the findings for each patient group in turn.

4.1. Language decline in naPPA

Cross-sectional studies of individuals with naPPA have found deficits in speech fluency, speech sound errors, and grammatical processing difficulty, leading to the inclusion of these features in clinical research criteria. The clinical presentation of their speech is described as effortful and agrammatic, with inconsistent speech sound errors (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). The presence of slowed and effortful speech is perhaps the most consistent finding in this PPA variant (Grossman et al., 1996; Grossman et al., 2013; Gunawardena et al., 2010; Hodges & Patterson, 1996; Wilson etal., 2010). We also observed deficits in grammatical processing. The present study highlights the progressive nature of impairments in fluency and grammar in naPPA, despite their having the shortest average disease duration. Even though naPPA patients were more impaired than all other participants at the initial time point in all of these domains, there was no evidence of a floor effect, and they were more impaired than the other groups at the second time point as well. They declined significantly over the course of the study on all four measures of fluency and grammaticality.

Slowed speech rate is observed to some extent in most neurodegenerative diseases (Ash et al., 2013; Grossman et al., 2013; Gunawardena et al., 2010), but it is most prominent in naPPA. In our data, the average speech rate at the time of first assessment was about half that of controls. As the disease progressed, average speech rate declined to one-third that of controls. Some degree of slowing has been found in almost every naPPA patient we have studied and has been found in speech samples of differing durations and task demands (Ash et al., 2013). In the present study, naPPA patients were significantly impaired on speech rate relative to both controls and bvFTD patients at Time 1. At Time 2, they were impaired relative to all other groups, and, as a group, they exhibited a significant decline from Time 1 to Time 2. This is similar to the findings of Brambati, et al. (2015), who found a decline in fluency as measured by the WAB in naPPA patients over the span of 1 year. Consistent with previous reports (Ash et al., 2009; Grossman et al., 2013; Gunawardena et al., 2010), we did not find a decline in executive and cognitive functioning that correlated with the decline in speech rate. Furthermore, speech rate did not correlate with speech errors in naPPA, making it unlikely that the interruptions to the flow of speech caused by these errors accounted for their slowed speech rate. Previous findings suggest, rather, that a grammatical processing impairment is a prominent factor contributing to the slowing of speech in naPPA (Grossman et al., 1996; Grossman et al., 2013; Grossman, Rhee, & Moore, 2005; Gunawardena et al., 2010; M.-M. Mesulam et al., 2009; Peelle, Cooke, Moore, Vesely, & Grossman, 2007). While there was no correlation of speech rate with measures of grammaticality at Time 1, significant correlations were found at Time 2 between speech rate and grammatical measures, and we found a significant correlation between slowed speech and reduced grammatical complexity in the production of dependent clauses. We also found no correlations between the production of speech errors and measures of grammatical expression in this patient group. These observations confirm our previous findings, and the extension of the relationship between fluency and grammaticality to a longitudinal cohort emphasizes the potential causal association between these domains of language functioning. Thus our results are consistent with previous cross-sectional studies (Gunawardena etal., 2010), and our longitudinal findings emphasize the suggestion that grammatical limitations are a factor in the reduction of speech rate in naPPA. These tentative findings call for further investigation.

In the present study, we did not distinguish between phonetic (“sound distortion”) and phonological (segment substitution) speech errors, as explained above, since we were concerned with the smooth flow of speech rather than with distinguishing different types of errors. Previous descriptions have established that speech errors are characteristic of naPPA (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2010), and this was also observed in the present study. The prominence of speech errors in this group was highlighted by the significant increase in the frequency of speech errors from Time 1 to Time 2. In the recent study of Brambati, et al. (2015), the cohort of naPPA patients did not exhibit an increase in paraphasic errors, which are phonological in nature, but they did increase significantly in the rating of apraxia of speech, which is associated with phonetic errors and distortions. Taken together, these results appear to be consistent with our findings. In our data, the increase in speech errors was not correlated with a decline in speech rate. Previous work has found a trend towards an association of phonetic errors with reduced speech rate in naPPA but no association of phonological errors with reduced speech rate (Wilson et al., 2010). We also did not find an association of speech errors with a decline on neuropsychological measures. The absence of a correlation of speech errors with reduced speech rate suggests that reduced speech rate is related to a language mechanism other than motor articulatory control.

Cross-sectional studies have identified deficits of grammatical comprehension in naPPA, and longitudinal studies also have shown progressive decline of grammatical comprehension in these individuals (Grossman & Moore, 2005; Rogalski, Cobia, Harrison, Wieneke, Weintraub, et al., 2011). In one recent study (Charles et al., 2014), naPPA patients were found to have comprehension difficulty for dependent clauses, even for sentences with the limited task demands of clefts, which have fewer propositions and are shorter, compared to sentences with center-embedded relative clauses, which contain more propositions and are longer. In the present study, we found parallel longitudinal results for speech production, with significant simplification of the grammatical structure of utterances. On initial testing, the frequency of dependent clauses of any type in naPPA was less than one-third that of healthy seniors, and over the course of an average of 18 months it declined to near zero.

Grammatical well-formedness is determined by a myriad of features. In the present study, some of the features of agrammatic speech included missing determiners, omitted subject noun phrases, unfinished sentences, utterances consisting only of a noun phrase, omitted auxiliaries, or nonagreement of a subject and verb, among other errors. The findings of our study contrast with those of Brambati, et al. (2015) in that we found a significant decline in grammaticality, while they found only a slight decline that was not statistically significant. This discrepancy may be due in part to methodological differences. As an alternative to limitations of linguistic competence, the omission of words or morphemes may reflect an economy of effort in PPA patients. It has also been proposed that executive deficits contribute in part to grammatical agreement errors in naPPA (Grossman et al., 2013; Gunawardena et al., 2010; M.-M. Mesulam et al., 2009). However, in the present study, we did not find evidence that cognitive functioning was correlated with the naPPA patients’ decline in linguistic competence, and naPPA patients did not decline significantly on measures of executive functioning. Thus it appears that decline in the grammatical well-formedness of utterances during language production cannot be explained fully in terms of general cognitive decline in these patients.

4.2. Language decline in svPPA

The hallmark of svPPA is loss of word meaning and object knowledge, most commonly demonstrated by poor performance on naming and lexical comprehension. Indeed, the svPPA patients in our study were impaired on the Boston Naming Test, a test of visual confrontation naming. Individuals with svPPA maintain both fluency and grammaticality over the course of several years. In the present study, of the features we examined, the svPPA group showed significant decline only on grammatical complexity, specifically, the frequency of dependent clauses within utterances. They also exhibited slowed speech rate, an elevated rate of speech errors at Time 1, and a reduced frequency of well-formed utterances at Time 2. The published criteria for svPPA list “spared speech production,” referring to grammar and motor aspects (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011) but a reduction in syntactic complexity has been observed previously in a cross-sectional study (Wilson et al., 2010), consistent with our findings. Brambati, et al. (2015) did not specifically examine this aspect of connected speech production, but our findings agree with theirs on the absence of change in other speech production variables. From the perspective that these patients lose word knowledge, one possibility is that svPPA may also lead to degraded knowledge of the grammatical properties of words, resulting in grammatical difficulty. Additional work is needed to evaluate this possibility.

4.3. Language decline in lvPPA

The impairments observed in lvPPA are somewhat similar to those of naPPA, and these two variants may be difficult to distinguish from each other clinically (Ballard et al., 2014; Croot, Ballard, Leyton, & Hodges, 2012; Graham et al, 2016; Grossman, 2012; M.-M. Mesulam, Wieneke, Thompson, Rogalski, & Weintraub, 2012). Individuals with lvPPA are reported to exhibit prominent deficits in both speech rate and frequency of speech errors, and this is consistent with our findings. The lvPPA patients studied by Brambati, et al. (2015) exhibited a trend to decline in aspects of fluency (p< 1), but not speech errors, during the interval between tests. In our study, these patients became significantly more impaired in their performance on both speech rate and speech errors over the course of the study. Such progression might be hypothesized to be a consequence of increasingly impaired single-word retrieval, and evidence for this was seen in their decline on the BNT and category fluency in naming animals. However, their change in performance on these tests did not correlate with change on any of the language variables we investigated, suggesting that word retrieval in the course of conversational speech may utilize a different mechanism from that of word retrieval during confrontation naming. For example, patients can use circumlocutions during conversational speech when they cannot retrieve a specific word, but this is not acceptable during confrontation naming. The source of speech slowing and increasing frequency of speech errors in lvPPA calls for further study.

An additional area of increasing impairment was found by Brambati et al. (2015) in the decline in the production of grammatically well-formed sentences. This feature is not mentioned in the criteria for lvPPA (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). Indeed, a secondary criterion for lvPPA is the absence of frank agrammatism, which would differentiate lvPPA from naPPA. We observed some decline in grammatical production, albeit inconsistently across sentence features, since these patients declined in the production of well-formed sentences but not in the production of dependent clauses.

Similarly, Brambati, et al. (2015) found a trend to decline in grammaticality (p<.1) in lvPPA over the interval between tests. A cross-sectional study of grammatical variables showed that lvPPA patients were impaired relative to controls, bvFTD, and svPPA on syntactic errors but less impaired than naPPA patients; additionally, lvPPA patients were not impaired relative to controls in the production of embedded clauses (Wilson et al., 2010). The association of speech errors as well as reduced speech rate with a decline in grammatical features in lvPPA suggests the possibility that word retrieval difficulty may contribute to grammatical deficits in this patient group. Another proposal has related grammatical difficulty to short-term memory difficulty, noting that grammatically complex sentences are also often longer than simple sentences. However, we did not find a relationship between grammatical features of sentence production and a measure of auditory-verbal short-term memory, forward digit span. Regardless of the basis for greater impairment with grammatical aspects of sentences, the emergence of impaired grammaticality over the course of disease in lvPPA may contribute to difficulty in distinguishing lvPPA from naPPA. Thus, the timing of assessment in relation to disease duration in lvPPA may affect diagnostic accuracy (Giannini et al., 2017). The grammaticality of lvPPA speech is an area for further investigation.

4.4. Language decline in bvFTD

bvFTD patients are not obviously aphasic, and their speech production is nearly free of speech errors. However, we have shown previously that these individuals exhibit slowed speech compared to controls (Ash, et al., 2006, 2013). In the longitudinal data of the present study, their speech rate declined significantly over time. This may be related in part to the emergence and progression of apathy, a well-recognized feature of disease progression in this condition. bvFTD patients also declined slightly in the production of well-formed sentences, with the result that their production was impaired relative to controls at Time 2 but not at Time 1, although their degree of decline did not reach statistical significance. For dependent clauses, they declined significantly from Time 1 to Time 2, and their production was impaired relative to controls at Time 2 but not at Time 1. Patients with bvFTD often exhibit difficulty on measures of executive functioning, and thus it is possible to speculate that grammatical simplification may be related in part to their executive limitations. While bvFTD patients significantly declined on a non-specific measure of overall cognitive functioning, and while they declined to a non-significant extent on a limited spectrum of executive measures, we did not observe a correlation between declining measures of speech production and declining performance on measures of cognitive functioning. Thus, their speech becomes slower and somewhat simplified with the progression of disease, even though they are not frankly aphasic. Additional work is needed to determine the basis for bvFTD patients’ decline on features of connected speech production.

4.5. Imaging

A number of recent studies have investigated the longitudinal progression of brain atrophy in patients with PPA and bvFTD (Brambati et al., 2015; Etcheverry et al., 2012; Faria et al., 2014; Heim et al., 2014; Knopman et al., 2009; Olm et al., 2016; Rogalski et al., 2014; Rohrer et al., 2013; Tetzloff et al., 2018; Tu et al., 2016), but few of these reports have related longitudinal language change to imaging. We identified areas of significant cortical thinning in the combined cohort of PPA and bvFTD patients at Time 1 and Time 2 compared to controls, and we evaluated the association of cortical thinning in those areas to decline on language measures.

Atrophy contrasts at both timepoints replicated prior studies of PPA, which have found strong left-lateralization of disease. We observed foci of CT in anterior and ventral temporal cortex (most commonly observed in svPPA), the frontal operculum and anterior insula (common in naPPA), and more posterior portions of middle/superior temporal cortex (characteristic of lvPPA) (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2004; Grossman, 2010). In the current study, declines in grammaticality (assessed by proportion of well-formed sentences) were associated with gray matter loss in left frontal operculum and anterior insula as well as bilateral temporal cortex, more prominently on the left than the right. The left frontal operculum/anterior insula is commonly reported both as an area of degeneration in naPPA (Nestor et al., 2003) and as an area whose activity is modulated by syntactic processing, although some investigators suggest that this may reflect domain-general rather than language-specific functions (Wilson et al., 2016). We have observed atrophy in anterior-superior portions of the left temporal lobe and related this to grammatical production deficits in naPPA (Gunawardena, et al., 2010).

Longitudinal associations with grammaticality also overlap closely with the results of a cross-sectional analysis by Ash et al. (2009), where cortical thickness was associated with speech rate. It is unclear why the current study did not also find an association with speech rate, but the differences from Ash et al. (2009) may be due to subtle factors such as the number and phenotypes of PPA patients included in the imaging analysis. We note that speech rate and grammaticality (i.e., production of well-formed sentences) were correlated with each other in both the current and previous studies (Ash et al., 2009). Additionally, anatomic correlates of fluency and syntactic complexity overlap (Wilson et al., 2010). Further research is warranted to determine whether dysfluency and agrammatism maybe anatomically dissociated in PPA.

Although atrophy results displayed a left-hemisphere bias, associations between cortical thinning and grammatical decline also implicated some right hemisphere regions in superior aspects of the temporal lobe. Of course, right-hemisphere associations with well-formed sentence production may simply reflect the fact that both of these variables are associated with atrophy in left-hemisphere language regions; such correlative evidence does not directly implicate the involvement of right hemisphere in speech production. Nevertheless, we cannot discount the possibility that patients may have recruited right-hemisphere areas homologous to left hemisphere language regions to compensate in part for degeneration in these left-hemisphere areas. While this interpretation is speculative, functional studies have previously found evidence for right-hemisphere reorganization of language function in PPA (Nelissen et al., 2011; Vandenbulcke, Peeters, Van Hecke, & Vandenberghe, 2005). Similar evidence of compensatory reorganization of language in aphasic patients comes from studies of stroke (Hope et al., 2017; Xing et al., 2016). Finally, Thiel et al. (2006) reported that patients with slowly progressing brain lesions recovered language function in right-hemisphere regions, while patients with rapidly progressing lesions did not, consistent with the hypothesis implicating right hemisphere homologues of left hemisphere language areas in the face of gradual neurological degeneration. However, additional work is needed to determine the functional consequences of the lateralization of disease in patients with PPA and bvFTD. More generally, the neuro anatomic predictors of decline in speech production in PPA and bvFTD call for further investigation.

5. CONCLUSIONS

While this study is among the first to relate neuroanatomy to longitudinal change in language performance, several caveats should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. First, longitudinal samples in these rare cases are difficult to collect since patients are frequently unavailable for follow-up, limiting the number of candidates for a longitudinal study, so our findings are limited by the small sample size. Likewise, for the neuroanatomic assessment, we only had a subset of participants available for imaging studies; some patients who are available for longitudinal testing are nevertheless excluded from MRI scan evaluations for reasons of safety or other complications, such as metal implants or claustrophobia. Furthermore, there was some variability in the interval between language testing sessions and also between testing sessions and imaging. Although we did not find a correlation of change in language performance with change in neuropsychological functioning, a larger data set including additional neuropsychological measures would provide greater confidence in our results.

With these caveats in mind, this study of the longitudinal development of impairments in speech production has found that naPPA patients decline significantly on fluency and grammatical measures of speech production. The repeated measures analysis did not show interactions of group by time for any of the four measures, so it cannot be said from the present available data that one group declines faster or to a greater extent that another; this limitation may be due to the small size of the patient cohorts. However, while our data do not demonstrate a difference in rate of decline among the patient groups, the naPPA patients were more impaired than those of all other groups at both time points. Only naPPA patients declined significantly on all four of the speech expression variables that we measured. These language deficits appear to be independent of each other at baseline, and their decline does not appear to be driven by a concomitant decline in non-language cognitive abilities. Nevertheless, this longitudinal study has shown that other PPA and bvFTD patients also declined in their speech over time. svPPA patients, traditionally regarded as “fluent,” exhibit significant decline by a progressive simplification of syntax, a change which can only become evident in longitudinal studies. Individuals with lvPPA showed significant decline in fluency over time, underlining the difficulty that has been observed in distinguishing these patients from those with naPPA (M.-M. Mesulam et al., 2012; Rogalski, Cobia, Harrison, Wieneke, Thompson, et al., 2011; Watson et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2010). They also declined significantly in the grammaticality of utterances, although they did not exhibit a concomitant simplification of grammatical structure. bvFTD patients differed from controls on speech rate, and they became more impaired on this measure over time. They also eventually became impaired on measures of grammar, but the change in their performance was significant only for grammatical complexity (dependent clause production). As in naPPA, these three groups did not show any correlation of decline on features of speech production with decline on non-language cognitive measures. Thus, the evaluation of speech production provides a unique contribution to the characterization of patients with PPA and bvFTD, with potential application to clinical practice. The areas of longitudinal decline that we have identified appear to be related to disease in an extended language network involving frontal and temporal regions as well as the insula. These are areas most often found to be atrophied in PPA, but they also exhibit degeneration in bvFTD. Thus, our focus on speech production further informs us about the real-world consequences for everyday interaction with family, friends, and caregivers that may be anticipated in patients with PPA and bvFTD.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

-

-

Language production declines over time in primary progressive aphasia (PPA)

-

-

Non-fluent/agrammatic PPA shows significant decline in speech fluency and grammar

-

-

Other PPA and bvFTD patients are less impaired but also decline in speech expression

-

-

Declining language expression is related to atrophy in an extended language network

Statement of Significance.

We examined spontaneous speech production longitudinally in three variants of primary progressive aphasia and behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Our results reveal decline in language expression in these conditions, with differences in the patterns of decline among the different patient groups. In addition, decline in language expression was not correlated with decline on non-language cognitive measures but appears to depend on disease in regions of an extended language network that are found across syndromes. These results of our longitudinal analysis contribute novel insight into the neurobiology of language.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH (AG017586, AG054519, AG052943, K23NS088341, K043503), Institute on Aging, Alzheimer’s Association (AACSF-18–567-131), Dana Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, and an anonymous contributor.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ash S, Evans E, O’Shea J, Powers I, Boiler A, Weinberg D, et al. (2013). Differentiating primary progressive aphasias in a brief sample of connected speech. Neurology, 81(4), 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash S, Moore P, Antani S, McCawley G, Work M, & Grossman M (2006). Trying to tell a tale: Discourse impairments in progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 66, 1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash S, Moore P, Vesely L, Gunawardena D, McMillan C, Anderson C, et al. (2009). Non-fluent speech in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 22, 370–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Wu J, Cook PA, & Gee JC (2011). An open source multivariate framework for n-tissue segmentation with evaluation on public data. Neuroinformatics, 9(4), 381–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard KJ, Savage S, Leyton CE, Vogel AP, Hornberger M, & Hodges JR (2014). Logopenic and nonfluent variants of primary progressive aphasia are differentiated by acoustic measures of speech production. PLoS One, 9(2), e89864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron D, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rabinovici GD, Santos-Santos MA, Seeley W, Miller BL, et al. (2018). Prevalence of amyloid-beta pathology in distinct variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol, 84(5), 729–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma P, & Weenink D (1992-2014). Praat, v. 5.3.76: Institute of Phonetic Sciences, University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner MF, Ash S, & Grossman M (2010). The new classification of primary progressive aphasia into semantic, logopenic, or nonfluent/agrammatic variants. Curr NeurolNeurosci Rep, 10(6), 484–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambati SM, Amici S, Racine CA, Neuhaus J, Miller Z, Ogar JM, et al. (2015). Longitudinal gray matter contraction in three variants of primary progressive aphasia: A tenser-based morphometry study. Neuroimage Clin, 8, 345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright P, Moss ΗE, Stamatakis EA, & Tyler LK (2008). Longitudinal studies of semantic dementia: the relationship between structural and functional changes over time. Neuropsychologia, 46(8), 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles D, Olm C, Powers J, Ash S, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, et al. (2014). Grammatical comprehension deficits in non-fluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 85(3), 249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Saad ZS, Britton JC, Pine DS, & Cox RW (2013). Linear mixed-effects modeling approach to FMRI group analysis. Neuroimage, 73, 176–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins KAQ, Ash S, Irwin DJ, & Grossman M (2017). Dissociable substrates underlie the production of abstract and concrete nouns. Brain Lang, 165, 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins KAQ, Ash S, Olm C, & Grossman M (2018). Longitudinal changes in semantic concreteness in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA). eNeuro, 5(6), ENEURO.0197– 0118.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins KAQ, & Grossman M (2017). Evidence of semantic processing impairments in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol, 30(6), 617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins KAQ, York C, Bauer L, & Grossman M (2016). Cognitive and anatomic double dissociation in the representation of concrete and abstract words in semantic variant and behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration. Neuropsychologia, 84, 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR, Reynolds RC, & Taylor PA (2017). FMRI Clustering in AFNI: False-Positive Rates Redux. Brain Connect, 7(3), 152–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croot K, Ballard K, Leyton CE, & Hodges JR (2012). Apraxia of speech and phonological errors in the diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic and logopenic variants of primary progressive aphasia. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 55(5), S1562–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry L, Seidel B, Grande M, Schulte S, Pieperhoff P, Sudmeyer M, et al. (2012). The time course of neurolinguistic and neuropsychological symptoms in three cases of logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 50(7), 1708–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria AV, Sebastian R, Newhart M, Mori S, & Hillis AE (2014). Longitudinal Imaging and Deterioration in Word Comprehension in Primary Progressive Aphasia: Potential Clinical Significance. Aphasiology, 28(8–9), 948–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen I, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun M, & Noll DC (1995). Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): Use of a cluster-size threshold. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 33, 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini LAA, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Ash S, Rascovsky K, Wolk DA, et al. (2017). Clinical marker for Alzheimer disease pathology in logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 88(24), 2276–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, & Kaplan E (1972). Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination. [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, et al. (2004). Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol, 55(3), 335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. (2011). Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology, 76(11), 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham NL, Leonard C, Tang-Wai DF, Black S, Chow TW, Scott CJ, et al. (2016). Lack of Frank Agrammatism in the Nonfluent Agrammatic Variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra, 6(3), 407–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M (2010). Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol, 6(2), 88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M (2012). The non-fluent/agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Lancet Neurol, 11(6), 545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M (2018). Linguistic Aspects of Primary Progressive Aphasia. Annual Review of Linguistics, 4(1), 377–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Mickanin J, Onishi K, Hughes E, D’Esposito M, Ding XS, et al. (1996). Progressive Nonfluent Aphasia: Language, Cognitive, and PET Measures Contrasted with Probable Alzheimer’s Disease. J Cogn Neurosci, 8(2), 135–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, & Moore P (2005). A longitudinal study of sentence comprehension difficulty in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 76(5), 644–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Powers J, Ash S, McMillan C, Burkholder L, Irwin D, et al. (2013). Disruption of large-scale neural networks in non-fluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia associated with frontotemporal degeneration pathology. Brain Lang, 127(2), 106–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Rhee J, & Moore P (2005). Sentence processing in frontotemporal dementia. Cortex, 41(6), 764–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena D, Ash S, McMillan C, Avants B, Gee J, & Grossman M (2010). Why are patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia nonfluent? Neurology, 75(7), 588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey ML, McMillan CT, Golob S, Spotorno N, Rascovsky K, Irwin DJ, et al. (2015). Getting on the same page: the neural basis for social coordination deficits in behavioral variant frontotemporal degeneration. Neuropsycho logia, 69, 56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim S, Pieperhoff P, Grande M, Kuijsten W, Wellner B, Saez LE, et al. (2014). Longitudinal changes in brains of patients with fluent primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang, 131, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR, & Patterson K (1996). Nonfluent progressive aphasia and semantic dementia: a comparative neuropsychological study. JInt NeuropsycholSoc, 2(6), 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR, & Patterson K (2007). Semantic dementia: a unique clinicopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol, 6(11), 1004–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope TMH, Leff AP, Prejawa S, Bruce R, Haigh Z, Lim L, et al. (2017). Right hemisphere structural adaptation and changing language skills years after left hemisphere stroke. Brain, 140(6), 1718–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KW (1965). Grammatical structures written at three grade levels. Champaign, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A (1982). Western Aphasia Battery. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Knibb JA, Woollams AM, Hodges JR, & Patterson K (2009). Making sense of progressive non-fluent aphasia: an analysis of conversational speech. Brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr., Kramer JH, Boeve BF, Caselli RJ, Graff-Radford NR, et al. (2009). Brain and ventricular volumetric changes in frontotemporal lobar degeneration over 1 year. Neurology, 72(21), 1843–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M, Wieneke C, Rogalski E, Cobia D, Thompson C, & Weintraub S (2009). Quantitative template for sub typing primary progressive aphasia. Arch Neurol, 66(12), 1545–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M, Wieneke C, Thompson C, Rogalski E, & Weintraub S (2012). Quantitative classification of primary progressive aphasia at early and mild impairment stages. Brain, 135(Pt 5), 1537–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Hurley RS, Geula C, Bigio EH, et al. (2014). Primary progressive aphasia and the evolving neurology of the language network. Nat Rev Neurol, 10(10), 554–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen N, Dupont P, Vandenbulcke M, Tousseyn T, Peeters R, & Vandenberghe R (2011). Right hemisphere recruitment during language processing in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci, 45(3), 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PJ, Graham NL, Fryer TD, Williams GB, Patterson K, & Hodges JR (2003). Progressive non-fluent aphasia is associated with hypometabolism centred on the left anterior insula. Brain, 126, 2406–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevler N, Ash S, Jester C, Irwin DJ, Liberman M, & Grossman M (2017). Automatic measurement of prosody in behavioral variant FTD. Neurology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olm CA, Kandel BM, Avants BB, Detre JA, Gee JC, Grossman M, et al. (2016). Arterial spin labeling perfusion predicts longitudinal decline in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol, 263(10), 1927–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelle JE, Cooke A, Moore P, Vesely L, & Grossman M (2007). Syntactic and thematic components of sentence processing in progressive nonfluent aphasia and nonaphasic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurolinguistics, 20(6), 482–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. (2011). Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain, 134(Pt 9), 2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Thompson CK, Weintraub S, et al. (2011). Anatomy of language impairments in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurosci, 31(9), 3344–3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, & Mesulam MM (2011). Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 76(21), 1804–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogalski E, Cobia D, Martersteck A, Rademaker A, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, et al. (2014). Asymmetry of cortical decline in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology, 83(13), 1184–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Caso F, Mahoney C, Henry M, Rosen HJ, Rabinovici G, et al. (2013). Patterns of longitudinal brain atrophy in the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang, 127(2), 121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer JD, Ridgway GR, Crutch SJ, Hailstone J, Goll JC, Clarkson MJ, et al. (2010). Progressive logopenic/phonological aphasia: erosion of the language network. Neuroimage, 49(1), 984–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzloff KA, Duffy JR, Clark ΗM, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Schwarz CG, et al. (2018). Longitudinal structural and molecular neuroimaging in agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 141(1), 302–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel A, Habedank B, Herholz K, Kessler J, Winhuisen L, Haupt WF, et al. (2006). From the left to the right: How the brain compensates progressive loss of language function. Brain Lang, 98(1), 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, Ballard KJ, Tait ME, Weintraub S, & Mesulam M (1997). Patterns of language decline in non-fluent primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology, 11, 297–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tree J, & Kay J (2015). Longitudinal assessment of short-term memory deterioration in a logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia with post-mortem confirmed Alzheimer’s Disease pathology. J Neuropsychol, 9(2), 184–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu S, Leyton CE, Hodges JR, Piguet O, & Hornberger M (2016). Divergent Longitudinal Propagation of White Matter Degradation in Logopenic and Semantic Variants of Primary Progressive Aphasia. JAlzheimersDis, 49(3), 853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Klein A, Song G, Das SR, Duda JT, et al. (2014). Large-scale evaluation of ANTs and FreeSurfer cortical thickness measurements. Neuroimage, 99, 166–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]