Abstract

Treatments that are efficacious in research trials perform less well under routine conditions; differences in supervision may be one contributing factor. This study compared the effect of supervision using active learning techniques (e.g. role play, corrective feedback) versus “supervision as usual” on therapist cognitive restructuring fidelity, overall CBT competence, and CBT expertise. Forty therapist trainees attended a training workshop and were randomized to supervision condition. Outcomes were assessed using behavioral rehearsals pre- and immediately post-training, and after three supervision meetings. EBT knowledge, attitudes, and fidelity improved for all participants post-training, but only the SUP+ group demonstrated improvement following supervision.

Keywords: Evidence-Based Treatments, Professional Supervision, Treatment Fidelity

Decades of development and testing have produced a large and growing evidence base for mental health treatments for youths and families (Chorpita et al., 2011; NREPP, 2014; Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008). Despite the large effects demonstrated in randomized clinical efficacy trials, these effects are tempered when the same treatments are delivered under conditions that more accurately represent typical care. Specifically, as the clients, clinicians, and settings become more characteristic of community mental health services, the benefit of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) over usual care is diminished (Spielmans, Gatlin, & McFall, 2010; Weisz et al., 2013). This “implementation cliff” (Weisz, Ng, & Bearman, 2014, p. 59) may be due to a number of factors, including the loss of fidelity to the active components of EBTs in typical care settings (Garland et al., 2013). Therefore, interventions to improve EBT fidelity may be crucial to close the gap between treatment efficacy and outcomes in practice settings (McLeod, Southam-Gerow, Tully, Rodriguez, & Smith, 2013; Weisz et al., 2014).

Treatment Fidelity is an Essential Aspect of Implementation

Treatment fidelity is defined as the extent to which a treatment is delivered as intended, and encompasses three factors: (a) competence refers to the skill and judgement levels of the therapists, (b) differentiation refers to the extent to which the intended treatment can be distinguished from others, and (c) adherence refers to the extent that prescribed technical elements of the treatment are present (McLeod et al., 2013; Schoenwald et al., 2011). In the early stages of testing treatment efficacy, treatment manuals were introduced to aid in the testing and replication of interventions, with the goal to increase intervention fidelity by supporting therapists in delivering treatments consistently (Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

Unfortunately, the use of a manual does not guarantee that an EBT is delivered with fidelity. Additional infrastructure beyond manuals may be necessary to implement EBTs with high fidelity. EBTs are comprised of specific practices believed to impact therapeutic mechanisms of change and are only based in evidence insofar as these practices are performed as intended. To better understand the infrastructure required to support EBT fidelity, it is helpful to consider the conditions in which these treatments are tested and shown to have clinical benefit for clients, and how these may differ from the conditions of routine care.

Clinical Training and Supervision May Support Treatment Fidelity

One of the distinctive, but often overlooked, characteristics of efficacy trials is the emphasis on thorough clinical training and supervision to develop and sustain therapist expertise and EBT fidelity. The term supervision is used here to describe ongoing clinical support related to the delivery of therapeutic services. Various terms are often used to describe similar types of support (e.g., consultation, coaching, and technical assistance) (Schoenwald, Mehta, Frazier, & Shernoff, 2013), with the meanings varying somewhat depending on the role of the support person and the relationship to the therapist delivering the intervention. Supervision typically refers to ongoing clinical support provided by an individual who is employed by the agency where the treatment is being delivered (Nadeem, Gleacher, & Beidas, 2013). Although a consultant (i.e. an individual who is external to the agency where the treatment is being delivered) could also provide the activities described, we chose to focus on supervision because it is a traditional requirement of most mental health accrediting agencies. Therefore, as others have noted, supervision might provide an opportunity to bring therapist behavior more in line with research-supported clinical practices using a process that already occurs in the great majority of youth mental health clinics (Schoenwald et al., 2008; 2013). Required pre-service clinical supervision may be particularly influential in the development of therapist competency, as therapists report that graduate school training is a key determinant of current practice (Cook, Schnurr, Biyanova, & Coyne, 2009).

Training and supervision in the randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that have established the benefit of EBTs for youth have a number of defining features, as described in a review of 27 “exemplary” treatment trials (Roth, Pilling, & Turner, 2010). Intensive initial training typically included a combination of didactic teaching, video exemplars, and role-playing. Supervision was similarly rigorous. Therapists received regular “model specific” supervision that focused on the particular practices of the treatment being tested, and treatment fidelity was carefully monitored in the majority of the trials. The authors noted that the results of RCTs must be considered in light of this attention to training and supervision: “What has actually been demonstrated is the impact of the therapeutic intervention in the context of dedicated training and supervision for trial therapists. This strongly suggests that services implementing evidence-based practice need to mirror … the training and supervision that enabled the intervention to be delivered effectively in the research context” (Roth et al., 2010, p. 296). Although perfectly replicating the intensity of training and supervision in RCTs is unlikely given the limited resources of many community settings, a better understanding of effective supervision practices could permit this naturally occurring process to be used to its best advantage.

Guidelines for supervision as a pre- and post-degree necessity and a core competency for training exist across mental health disciplines (American Board of Examiners in Clinical Social Work, 2004; Association for Counselor Education and Supervision Taskforce on Best Practices, 2011; Fouad et al., 2009; Kaslow et al., 2004). These guidelines focus largely on broad issues (e.g., consistency and duration of supervision), and few specify the details of supervision process. Theoretically, supervision serves key functions summarized by Milne (2009) as normative (oversight of quality control and client safety issues), restorative (fostering emotional support and processing) and formative (facilitating supervisee skill development). Only a handful of studies related to supervision have empirically examined the relation of supervision to supervisee skill or behavior, or to client outcome (Wheeler & Richards, 2007). The methodological shortcomings of this literature, including the lack of random assignment, lack of control conditions, reliance on self report data, lack of a multi-rater observational approach, and limited connection between supervision process and therapist behavior (Watkins, 2014), make it challenging to identify particular aspects of supervision that comprise best practices. There is some evidence that ongoing supervision can increase EBT fidelity relative to initial training only. A meta-analysis of 21 studies assessing Motivational Interviewing (MI) implementation in routine care settings found that studies that did not provide post-training feedback and/or coaching saw diminishing therapist skill with MI over a six-month period, while those studies that provided ongoing support showed small skill increases over the same period (Schwalbe, Oh, & Zweben, 2014). This underscores the importance of supervision generally, but does not identify critical components of supervision that may facilitate therapist skill development.

In contrast, James, Milne, & Morse (2008) have promoted an emphasis on specific “micro-skills” that develop supervisee competence, suggesting that activities such as summarizing, giving feedback, checking theoretical knowledge, and using experiential learning (e.g., modeling, role-play) provide “scaffolding” that guide the development of high-fidelity practice. Likewise, Bennett-Levy and colleagues (2006, 2009) suggest that successful therapist training must engage three principal systems—declarative, procedural, and reflective—and draws from experiential learning theory (Kolb, 1984) to describe the theoretical process by which declarative knowledge is transformed into procedural action. Experienced CBT therapists reported that modeling, role-play, and self-reflective practice were most helpful in the development of procedural skills in therapy (Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling, & Fennell, 2009).

Although very few studies have directly investigated the impact of these types of micro-skills on treatment fidelity, effectiveness and dissemination studies of EBTs can suggest potentially effective training practices (Rakovshik & McManus, 2010). In a study of community therapist implementation of EBTs for youth anxiety, depression, and disruptive conduct, particular processes used in supervision meetings (supervisor skill modeling and therapist role-play of practices) predicted implementation fidelity, whereas discussion of practices in supervision meetings did not (Bearman et al., 2013). Supervision processes have likewise been linked to therapist adherence and youth outcomes in effectiveness trials for youth treated with Multisystemic Therapy (MST; Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Chapman, 2009). The MST supervision model specifies a focus on particular practices consistent with the treatment model and development of therapist competencies during supervision meetings, as well as regular feedback regarding therapist adherence to MST practice use during sessions (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Liao, Letourneau, & Edwards, 2002). Greater use of the MST supervision model predicted therapist adherence as well as youth outcomes (Schoenwald et al., 2009). Taken together, it would seem that model-specific supervision that uses active strategies, evaluates competencies, and provides feedback increases implementation fidelity. Because supervision practices were not directly manipulated in these studies, however, we cannot establish a causal relation.

Supervision “As Usual” May Lack Some Critical Elements

The existing research on supervision components makes a promising case for the utility of specific supervision “micro-skills” to support EBT implementation. There is also clear evidence that successful treatment studies include both intensive training and ongoing supervision, and use the types of strategies recommended by both the scaffolding and experiential learning theory models of clinical supervision. In contrast, the little research that has been done to characterize therapist learning as it occurs in routine care suggests that (a) typical post-service training in EBTs consists of brief workshops with limited follow-up, and largely fails to result in EBT proficiency (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010); and (b) typical post-service supervision entails limited focus on implementing specific evidence-based practices, and rarely makes use of recordings or live supervision as a measure of quality assurance (Accurso, Taylor, & Garland, 2011). In short, training and supervision in routine care appear to differ markedly from the practices used in the RCTs where treatment efficacy is established. If EBT effectiveness is predicated on high-fidelity delivery of the treatment, then it is perhaps not surprising that treatments trialed with optimal supervisory infrastructure fare less well when implemented with less support. Developing guidelines for effective supervision that arise from the same type of rigorous research used to establish effective treatments may assist in improving the implementation of these treatments and improve the quality of mental health care in routine settings.

In order to more directly assess the relation between clinical supervision and treatment fidelity, we need experiments that randomly assign therapists to different supervision conditions and manipulate the processes of interest, including modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback. Thus, the current study used a randomized analogue experimental design to carefully control for the effect of supervision processes on demonstrated treatment fidelity to a specific evidence-based practice, cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring is defined as “the disputing of dysfunctional or irrational thoughts” (Ellis, 2009, p. 189) and theoretically disrupts the process by which maladaptive cognitions lead to maladaptive behaviors and emotions in numerous cognitive-behavioral models of disorder (Leahy & Rego, 2012). We chose to focus on cognitive restructuring because it has been identified as a practice that occurs with high frequency in EBTs for a number of common youth problem areas (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009). To address limitations of prior research, we included repeated observations of therapist behavior with a standardized confederate client rather than self-report.

Method

Participants

Forty mental health trainees at a large Northeastern university participated in the study in two cohorts. Participants included students enrolled in Clinical Psychology and School-Clinical Child Psychology doctoral programs at a professional school of psychology, and students in Masters’ training programs in Social Work and Mental Health Counseling. Participants were excluded if they had prior practical experience conducting cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or extensive experience practicing CBT techniques. Participants were 90% women and 67.5% Caucasian. They averaged 24.72 years of age and had, on average, 1.4 years of clinical experience prior to the study. The majority of trainees reported that their primary theoretical orientation was Cognitive, Behavioral, or Cognitive-Behavioral (50%), with others describing their primary theoretical orientation as Psychodynamic (17.5%), or Integrated/Other (27.5%). Characteristics of participating trainees are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 40 Participating Trainees

| Characteristics | Total (N = 40) |

SAU (N = 19) |

SUP+ (N=21) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (S.D.) [Range] |

Mean (S.D.)[Range] |

Mean (S.D.) [Range] |

||

| Age | 24.72 (2.26) | 25.42 (2.65) [22 – 32] |

25.05 (1.61) [22 – 28] |

t(37) = 1.97, p = .06 |

| Years of clinical experience |

1.40 (1.48) | 1.58 (1.75) [0 – 8] |

1.23 (1.19) [0 – 5] |

t(37) = .74, p = .46 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | X2(1) = 0.11, p = .92 | |||

| Female | 36 (90) | 17 (89.5) | 19 (90.5) | |

| Male | 4 (10) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | X2(3) = 1.68, p = .64 | |||

| Caucasian | 27 (67.5) | 14 (73.7) | 13 (61.9) | |

| Asian | 3 (7.5) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Latino | 4 (10) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Other/Mixed | 3 (7.5) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Mental Health Program |

X2(4) = 0.40, p = .98 | |||

| Mental Health Counseling, MA |

8 (20) | 3 (15.8) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Social Work, MSW |

4 (10) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Clinical Psych., Psy.D |

10 (25) | 5 (26.3) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Clinical Psych., Ph.D. |

8 (20) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (19.0) | |

| School-Clinical Psych., Psy.D. |

10 (25) | 5 (26.3) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Theoretical Orientation |

X2(2) = 0.43, p = .81 | |||

| Psychodynamic | 7 (17.5) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (19) | |

| Behavioral/CBT | 20 (50) | 11 (57.9) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Other/Integrated | 11 (27.5) | 5 (26.3) | 6 (28.6) |

Procedures

Recruitment and consenting of participants

Trainees in four mental health graduate training programs at a large Northeastern university were provided with information about this study via brief presentations in classrooms, direct emails, and flyers posted near program classrooms. Interested trainees were informed that the purpose of the project was to examine the impact of a training and supervision model in an evidence-based practice for the treatment of youth depression (cognitive restructuring). They were told they would be randomly assigned to one of the two supervision approaches, either approach A, the approach most often used in mental health clinics, or approach B, which was developed by the experimenters. If they were interested, trainees were offered one of several potential workshop dates. Prior to the training, each participant provided written consent and then completed baseline measures.

Participants were informed that there would be an initial training workshop, followed by three supervision meetings. They were informed that they would complete a brief behavioral rehearsal with a simulated client prior to the training, after the training, and after each supervision meeting, and that these would be video recorded. Participants then participated in their first behavioral rehearsal followed by the initial training workshop.

Training

Participants attended a three-hour workshop on cognitive restructuring for treating youth depression. The workshop used didactic presentation, video examples, live modeling by the instructor, and role-plays. After completing the training, participants were randomly assigned to one of two supervision groups.

Supervision

Supervision groups met for one hour a week for three weeks following the training. Supervision as Usual (SAU) sessions consisted of rapport building, agenda-setting, case narrative and conceptualization, planning for subsequent sessions, discussing alliance, and case management/administrative issues (Accurso et al., 2011). Supervision using scaffolding and experiential learning strategies (SUP+) consisted of rapport building, agenda-setting, case narrative and conceptualization, planning for subsequent sessions, performance feedback based on recording review, and modeling and role-playing with continued feedback. Supervision groups were comprised of up to three supervisees and one (n = 6) or two (n = 11) supervisors, who were members of the research team. Novice supervisors initially co-led supervision groups with a doctoral-level supervision veteran, and were then paired to lead groups together. Veteran supervisors led groups alone once novice supervisors were trained. All therapist trainees attended three supervision meetings. All supervisors led both types of groups. To ensure supervisor fidelity to the appropriate supervisory techniques, supervisors attended a training workshop led by the first author (masked for review), during which they received detailed supervision content outlines for both types of supervision. Additionally, supervisors watched videotapes of supervision sessions led by veteran supervisors from the relevant supervision type, selected by the first author, in order to increase fidelity to supervision structure. Finally, all supervision sessions were videotaped and reviewed throughout the study by the first author, and feedback was provided to supervisors. To verify that supervision conditions were adherent to their respective models, recorded supervision sessions were coded by the second and third author using a microanalytic coding system that identified the presence or absence of each of 12 supervision activities in five minute increments. The coders were not blind to supervision condition. A subset (10%) was double coded to ensure acceptable agreement between coders (M ICC = .64). All available sessions were coded (N = 40); some sessions were excluded due to errors in recording or inaudible quality. Independent sample t tests showed that the conditions differed with regard to percentage of five-minute increments spent on these activities, in the expected directions. The results of the adherence coding and the t tests are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Percentage of Five-Minute Increments Spent on Supervision Activities: Means, Standard Deviations, and Results from Independent Samples T-Tests

| Supervision Activity | SAU (N = 19) |

SUP+ (N=21) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Statistics | |

| Rapport Building | 21.26 | 20.77 | 8.72 | 7.36 | t(39) = 2.63, p = .01 |

| Agenda Setting | 9.38 | 7.26 | 10.18 | 3.97 | t(39) = −0.45, p = .66 |

| Case Narrative and Conceptualization |

45.43 | 25.57 | 12.16 | 16.85 | t(39) = 4.88, p < .001 |

| Cognitive Restructuring Discussion |

29.90 | 18.21 | 21.29 | 16.66 | t(39) = 1.62, p = .11 |

| Planning for Subsequent Session |

11.91 | 15.93 | 2.82 | 5.53 | t(39) = 2.48, p = .02 |

| Therapeutic Alliance Discussion |

9.14 | 8.81 | 1.37 | 3.47 | t(39) = 3.78, p = .001 |

| Administrative Work | 19.22 | 10.09 | 5.27 | 7.26 | t(39) = 5.18, p < .001 |

| Case Management | 8.40 | 13.94 | 0.00 | 0.00 | t(39) = 2.76, p = .009 |

| Modeling | 0.44 | 2.05 | 63.37 | 18.40 | t(39) = −15.94, p < .001 |

| Role-Play | 0.00 | 0.00 | 39.94 | 24.76 | t(39) = −8.61, p < .001 |

| Corrective Feedback | 0.00 | 0.00 | 74.57 | 14.85 | t(39) = −23.57, p < .001 |

| Checkout | 7.56 | 7.50 | 5.55 | 5.46 | t(39) = .998, p = .32 |

Behavioral rehearsals with standardized client

Cognitive restructuring fidelity as well as CBT expertise and global competency were assessed using a behavioral rehearsal paradigm (Beidas, Cross, & Dorsey, 2014) with standardized clients pre- and post-training, and following each of the supervision meetings. All of the “clients” were 12-year-old girls struggling with life stressors and symptoms of depression. Vignettes for each client were developed to be equivalent in terms of severity and representativeness, and were rated by five youth depression experts as comparable on these domains, following procedures suggested by Beidas and colleagues (2014). Confederate clients were four young adult female research assistants who received standardized training (four hours) and completed three practice behavioral rehearsals with the first author, and who took on the role of one client for the duration of the study. The confederate actors had information regarding the backstory of the client they portrayed, as well as the four vignettes used for each of the behavioral rehearsals, and scripted responses to use during the cognitive restructuring process. All confederate clients were blind to participant condition.

Behavioral rehearsals were standardized across conditions. Participants completed a standard first behavioral rehearsal prior to the training and were then randomly assigned to one of three confederate clients, each of whom had four vignettes. The order of the vignettes was balanced across participants to control for order effects. Prior to each of the recorded behavioral rehearsals, participants received the vignette for the upcoming session and the goals of the behavioral rehearsal, which were to help the client identify and restructure negative cognitions. The behavioral rehearsals were completed via the internet-based video communication system, Skype, and were video recorded and coded by raters blind to study hypotheses and to the training condition of the participants. Coders were two graduate research assistants who received a half-day didactic training in the coding systems (TIEBI and CBTCOMP-YD) and then completed practice coding under the supervision of the second and third authors, using a coding manual that defined each item and provided exemplars as well as differentiation from other items. Prior to coding the study sample, the coders passed a reliability test demonstrating adequate agreement (M ICC > .60) with expert raters on three recordings. Fifteen percent of the behavioral rehearsals were double-coded to assess inter-coder agreement.

All participants completed a demographic questionnaire before the training and measures of attitudes towards EBTs and declarative knowledge of cognitive restructuring prior to and immediately after the initial training workshop. Following each role-play, participants completed a satisfaction index, administered via an online secure survey system.

Measures

Modified Therapist Background Questionnaire (TBQ)

This six item self-report measure collects information about the participant’s gender, age, ethnicity, highest level of education received as well as prior clinical experience, including type of training, theoretical orientation, and typical client demographics.

The Modified Practice Attitudes Scale (MPAS)

An eight item self-report measure of provider attitudes towards evidence based practice (Borntrager, Chorpita, Higa-McMillan, & Weisz, 2009). Participants respond on a four-point Likert-scale (0 = not at all, 4 = to a very great extent) the extent to which they agree with statements with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes. The MPAS had good internal consistency (α = .80) in a sample of 59 community providers (Borntrager et al. 2009). In the current study, internal consistency (α = .77), and test-retest (r = .65) were acceptable.

Knowledge Test

A 15-item test assessing declarative knowledge of cognitive restructuring for youth depression and was developed specifically for this project. Possible scores ranged from 0–15. The total score was the total number of correct items. Two-day test re-test reliability in a sample of 22 participants ranged from r = .69 to r = 1.0.

Therapist Integrity to Evidence Based Interventions (TIEBI)

The TIEBI (Bearman, Herren, & Weisz, 2012) is a microanalytic system for coding sessions for the fidelity with which a therapist utilized evidence-based therapeutic techniques used to treat anxiety, depression, and disruptive conduct (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009). Scores on this measure reflect both adherence (presence of prescribed items) and competency (skillfulness), and can range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating better practice fidelity. The TIEBI was adapted from a previous coding system in order to merge overlapping items (Weisz et al., 2012). This version has shown excellent levels of coder agreement for a sample of community therapists delivering both EBP and usual care (M ICC = .78; Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981). Only relevent items related to treatment of youth depression were used in this project. Double-coded recordings (15% of sample) showed high levels of inter-coder agreement for both microanalytic three-minute practice frequency of items (M ICC = .77) and global item fidelity (M ICC = .83).

Manual for the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Competence Observational Measure of Performance with Youth Depression (CBTCOMP-YD; Lau & Weisz, 2012)

The CBTCOMP-YD is a coding system to measure therapist competence in the delivery of CBT for youth depression, and consists of 21 items assessing aspects of specific practices. For the purpose of this study only the expertise quality dimension and global CBT competence measure were utilized. The expertise quality dimension was scored on a three-point Likert-scale (1 = novice, 3 = expert). The global CBT competence item assesses proficiency with general CBT practice (overall skillfulness in the session with CBT characteristics such as agenda-setting, homework review and assignment, mood monitoring, and Socratic questioning) and was scored on a 10-point Likert-scale (1 = novice, 5 = intermediate, 10 = expert). In the current sample, blind coders demonstrated strong interrater reliability on the global CBT competence and CBT expertise measures summary scores (M ICC = .78).

Therapist Satisfaction Inventory (TSI)

Therapist satisfaction with the treatment approach was assessed using the effectiveness subscale items of the TSI, a therapist-report measure containing statements about beliefs and attitudes about the treatment approach just used (Chorpita et al., 2015). Three items reflect the therapist’s perception that s/he delivered an effective treatment (“The approach I used allowed me to work from interventions that have been demonstrated to be effective”). All items were worded such that higher scores indicated greater therapist satisfaction; scores ranged from 0 to 15. In a community sample of clinicians, internal consistency was acceptable (α = .81; Chorpita et al., 2015). Internal consistency was high for the Effectiveness Subscale of the TSI in this sample (α = .88).

Analyses

Data were screened for outliers. There were no missing data for any outcome. Descriptive analyses were completed to identify baseline (pre-training) means on all outcomes, and all baseline characteristics were compared using independent group t-tests and chi square analyses for both study conditions to ensure randomization resulted in equivalent groups on these variables. To test the effect of training on declarative knowledge and attitudes towards EBTs, we used paired sample t tests comparing these variables at pre-training and immediately post-training, prior to randomization. To analyze the effect of time, condition, and time X condition on all of the fidelity outcomes assessed via behavioral rehearsal, we used mixed-effects repeated measures models for each outcome (cognitive restructuring fidelity, CBT expertise, and global CBT competence) run in R (R Core Team, 2015), using the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015). Predictors in the analyses were experimental condition, time, and the interaction of the two (to identify whether conditions showed differential change over time). The model for these analyses is as follows:

I is an indicator function, in which I = 0 when time = 0 (at the first assessment) and I = 1 when time > 0. The indicator denotes that the training occurred, while the linear term indicates the passage of time. The intercept, β0i for each participant i, has mean γ00 and random error r0i that is normally distributed with mean 0 and some variance, , which is the between-groups variance. There is also random error ∈it for each participant that is normally distributed with mean 0 and variance which is the within-groups variance. The model allows outcomes to vary by condition in average baseline values, average values after the training, and, most importantly, in their slopes or time-trends after the training and over the course of the three supervision meetings.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the demographic factors including age, gender, ethnicity, years of clinical experience, clinical orientation, and graduate program for all participants, and separately for those in the SAU and SUP+ conditions, as well as independent group t-tests and chi squares comparing the two groups on these characteristics. Table 3 reports means and standard deviations for the declarative knowledge, attitudes, and baseline integrity for all participants, and separately for those in the SAU and SUP+ conditions, as well as independent group t-tests comparing the two groups at baseline. Participants did not differ significantly by conditions on any demographic or professional characteristics, or outcome variables at baseline.

Table 3.

Baseline Measure Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges, and Results from Independent Samples T-Tests

| Total (N= 40) |

SAU (N =19) |

SUP+ (N=21) |

Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (S.D.) |

Range | Mean (S.D.) |

Range | Mean (S.D.) |

Range | ||

| Declarative Knowledge |

9.58 (2.48) |

4 – 14 | 9.53 (2.20) |

5 – 14 | 9.62 (2.77) |

4 – 14 | t(38) = −.12, p = .91 |

| Attitudes towards EBTs |

2.84 (.58) |

1 – 3.63 | 2.95 (.47) |

2.13 – 3.63 |

2.74 (.65) |

1 – 3.63 | t(38) = 1.15, p = .26 |

| Cognitive Restructuring Fidelity |

1.28 (.64) |

0 – 3 | 1.32 (.67) |

0 – 3 | 1.24 (.62) |

0 – 2 | t(38) = .38, p = .71 |

| Global CBT Competence |

2.68 (1.23) |

1 – 5 | 2.68 (1.29) |

1 – 5 | 2.67 (1.20) |

1 – 5 | t(38) = .05, p =.97 |

| CBT Expertise | 1.15 (.36) |

1 – 2 | 1.16 (.37) |

1 – 2 | 1.14 (.36) |

1 – 2 | t(38) = .13, p = .90 |

| Statements of Affirmation |

1.0 (1.18) |

0 – 3 | 0.84 (1.21) |

0 – 3 | 1.14 (1.15) |

0 – 3 | t(38) = .43, p = .79 |

| Positive Regard |

0.60 (1.01) |

0 – 3 | 0.68 (1.11) |

0 −3 | 0.52 (0.93) |

0 – 3 | t(38) = .50, p = .62 |

| TSI Effectiveness |

9.08 (2.51) |

0 – 13 | 9.58 (2.59) |

0 – 13 | 8.62 (2.40) |

0 – 13 | t(38) = 1.22, p = .23 |

Effect of Training on Attitudes and Knowledge

Similar to other samples of mental health trainees, attitudes towards evidence-based practices were moderately positive before the training in cognitive restructuring (M = 2.83, SD = 0.58) (Bearman, Wadkins, Bailin, & Doctoroff, 2015; Nakamura, Higa-McMillan, Okamura, & Shimabukuro, 2011), with overall agreement with positive statements about EBTs between “a moderate” and “a great extent.” Attitudes were significantly more positive after the training for all participants, with overall agreement “to a great extent” with positive statements about EBTs (M = 3.02, SD = .45), t(38) = −2.71, p = .01, d = .43. In terms of declarative knowledge, trainees earned an average score of 9.58 out of 15, on the knowledge test prior to the training, corresponding to a score of 64% out of a possible 100% and earned an average score of 12.25 out of 15 following the training, corresponding to a score of 82% out of 100%. This change was significant, t(39) = −10.32, p <.001, d = 1.63.

Effect of Training and Supervision on Therapist Fidelity

Mixed-effects repeated measures models tested whether participants in the SUP+ group demonstrated higher levels of treatment integrity with cognitive restructuring, CBT expertise, and global CBT competence, from pre-training to immediately following the training, and after each of three supervision meetings relative to those in the SAU condition.

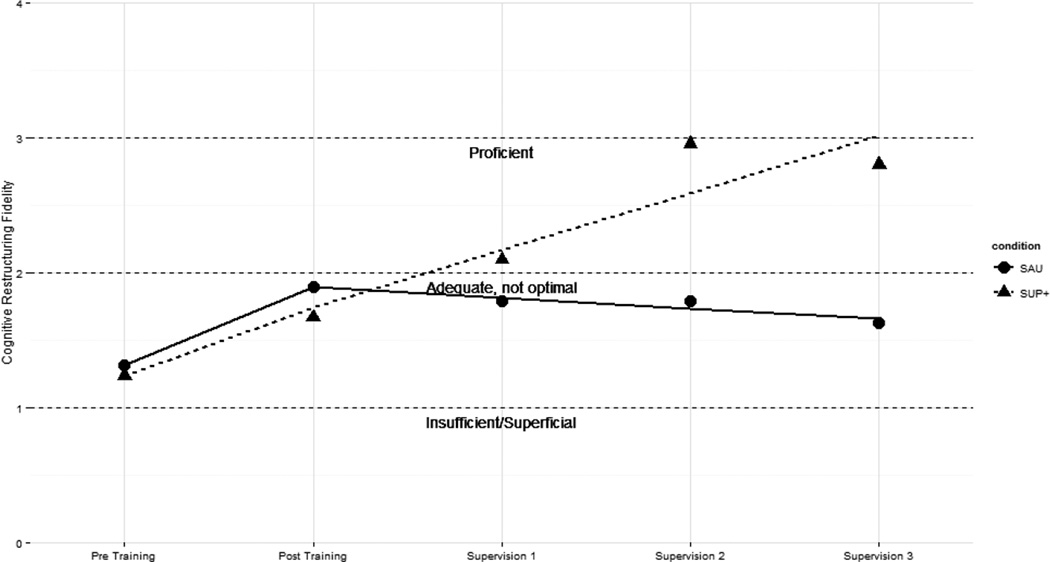

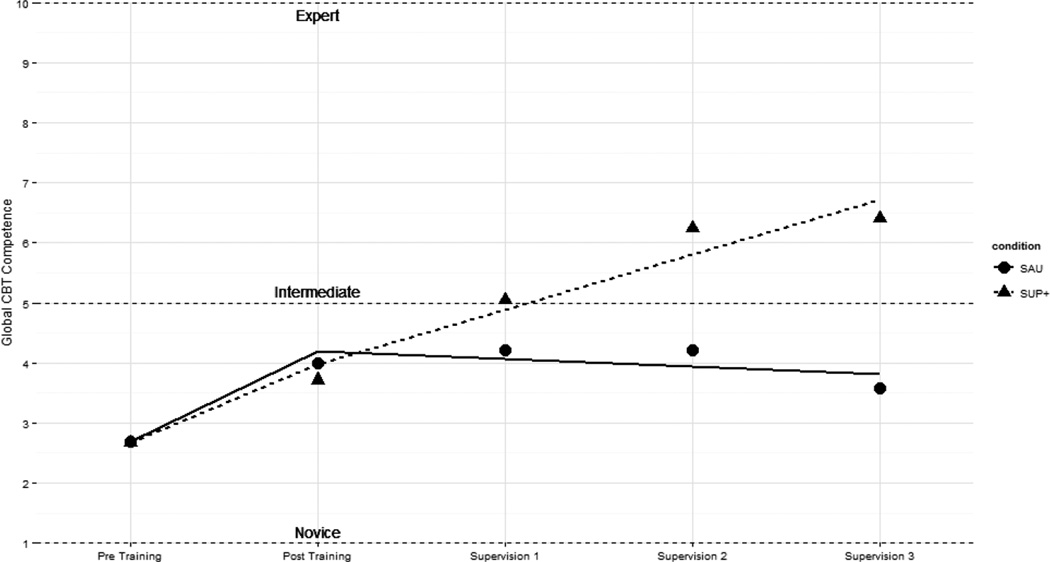

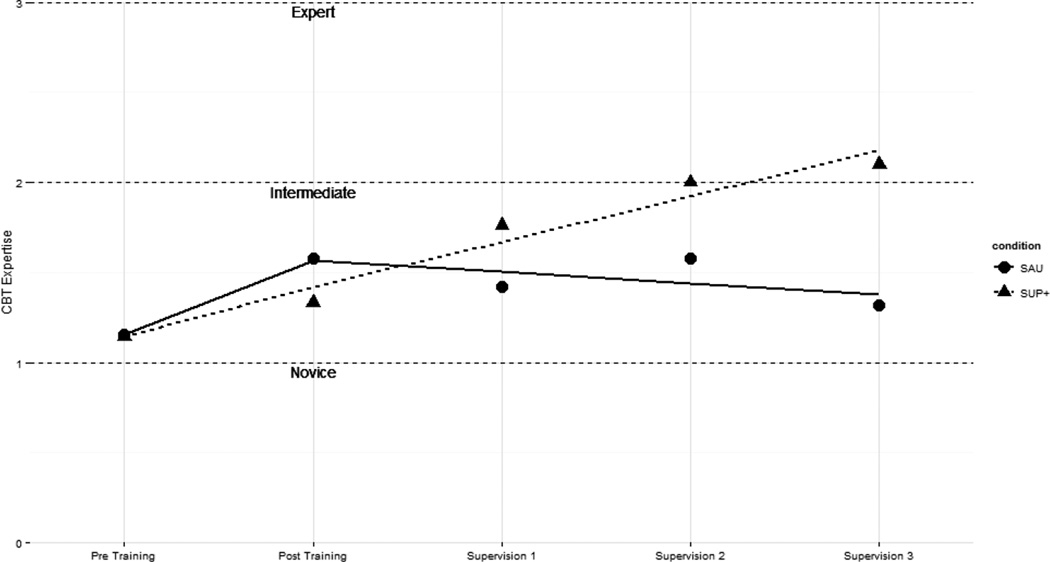

There was a main effect of the training in cognitive restructuring on cognitive restructuring fidelity, β = .67, t = 3.02, p = .003, d = .95, CBT expertise, β = .47, t = 2.94, p = .004, d = .91, and global CBT competence, β = 1.63, t = 3.61, p < .001, d = 1.00 suggesting that both conditions improved significantly from pre-to-immediately post training on all three observational outcomes. For all three outcomes, participants’ ratings as reported by blind coders improved modestly, corresponding with “adequate but not optimal,” for cognitive restructuring fidelity immediately following the training, and with a “novice” rating for both CBT expertise and global competence. The group-by-time interaction beginning after the immediate post-training assessment and over the course of the three supervision meetings was also significant for cognitive restructuring integrity, β = .504, t = 5.88, p < .001, d = .63, CBT expertise, β = .32, t = 4.99, p < .001, d = .70, and global CBT competence, β = 1.04, t = 5.87, p < .001, d = .64, indicating that the rate of change for the SUP+ condition was significantly more positive than those that of the SAU condition, as rated by blind coders. There was no significant effect of time or condition on any outcomes over the course of the three supervision meetings. Figures 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the estimated intercepts and slopes for observed integrity for both groups on these outcomes from pre-to immediately post-training and after each supervision meeting. The results of the mixed-effects models are reported in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Estimated intercepts and slopes of cognitive restructuring fidelity.

Figure 2.

Estimated intercepts and slopes for global CBT competence.

Figure 3.

Estimated intercepts and slopes for CBT expertise.

Table 4.

Results of the Mixed-Effects Models for Cognitive Restructuring Fidelity, Global CBT Competence, and CBT Expertise

| Parameters | β | SE | 95% CI | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Restructuring Fidelity | |||||

| Condition | −0.08 | 0.23 | (−0.53, 0.37) | 0.34 | p = .74 |

| Time | −0.08 | 0.06 | (−0.20, 0.4) | 1.28 | p = .20 |

| Training | 0.66 | 0.22 | (0.23, 1.08) | 3.02 | p = .003 |

| Condition X Time | 0.50 | 0.09 | (0.34, 0.67) | 5.88 | p < .001 |

| Condition X Training | −0.58 | 0.30 | (−1.17, 0.01) | 1.93 | p = .06 |

| Constant | 1.32 | 0.17 | (0.99, 1.64) | 7.82 | p <.001 |

| Global CBT Competence | |||||

| Condition | −0.02 | 0.52 | (−1.02, 0.99) | 0.03 | p = .97 |

| Time | −0.13 | 0.13 | (−0.38, 0.12) | 0.99 | p = .32 |

| Training | 1.63 | 0.45 | (0.75, 2.51) | 3.61 | p < .001 |

| Condition X Time | 1.04 | 0.18 | (0.70, 1.39) | 5.87 | p < .001 |

| Condition X Training | −1.24 | 0.63 | (−2.46, −0.03) | 1.99 | p = .05 |

| Constant | 2.68 | 0.38 | (1.95, 3.41) | 7.13 | p <.001 |

| CBT Expertise | |||||

| Condition | −0.02 | 0.16 | (−0.32, 0.29) | 0.10 | p = .93 |

| Time | −0.06 | 0.05 | (−0.15, 0.03) | 1.39 | p = .17 |

| Training | 0.47 | 0.16 | (0.16, 0.79) | 2.34 | p = .004 |

| Condition X Time | 0.32 | 0.06 | (0.19, 0.44) | 4.99 | p < .001 |

| Condition X Training | −0.45 | 0.22 | (−0.88, −0.02) | 2.02 | p = .04 |

| Constant | 1.16 | 0.12 | (0.93, 1.38) | 10.05 | p <.001 |

Exploratory analyses examined whether participants improved on therapeutic practices thought to be non-specific to any one theoretical model, so-called “common factors” (Laska, Gurman, & Wampold, 2014). Specifically, coders assessed the extent that therapists used statements of affirmation and validation with clients in each of the behavioral rehearsals. Both groups improved significantly from the first (pre-training) to the second (immediately post-training) assessment, β = 1.00, t = 2.53, p = .01, d = .84, but there were no significant interactions between time and condition, and there was no further improvement after the second assessment. Additionally, we examined participant ratings of satisfaction following each role-play. All participants reported increases in satisfaction with the treatment they had delivered from pre-to-immediately post training, β = 2.66, t = 4.38, p < .001, d = 1.34, and this level of satisfaction was maintained following each supervision meeting with no significant condition-by-time interaction.

Discussion

Clinical supervision is considered a core competency across numerous mental health disciplines, yet clinical supervision in routine care is overwhelmingly implemented without empirically supported guidelines and deviates substantially from the approaches used in the RCTs that establish treatment benefit of specific treatments (Accurso et al., 2011; Roth et al., 2010). Clinical supervision has been theorized to be the most important factor in developing competencies in mental health practice (Falender et al., 2004, Stoltenberg, 2005), but the specific aspects of supervision that lead to high quality treatment are not well understood. This is particularly relevant to the ongoing challenge of successfully moving scientifically supported EBTs from the research settings where they were developed and tested—often with extensive supervisory support—into routine care settings where most youths and families are treated. Because these treatments require prescribed components delivered skillfully, their success is reliant on implementation with fidelity. Treatments with robust effects in RCTs become less potent as they cross the “implementation cliff” (Weisz et al., 2014, p.59), so developing an evidence base for supervision practices that improve EBT fidelity is critical.

The current study took a step in that direction by directly manipulating supervision practices speculated to be helpful for the development of EBT fidelity in an analogue experiment. Mental health trainees who were inexperienced in the delivery of CBT strategies attended a training workshop on cognitive restructuring for youth depression and were randomly assigned to one of two supervision conditions. The supervision conditions were designed to reflect either what has been reported as typical in outpatient mental health services for youths (Accurso et al., 2011), or what has been suggested as helpful in improving therapist fidelity and client outcomes in effectiveness trials of EBTs (Bearman et al., 2013; Schoenwald et al., 2009) and recommended by the theoretical literature about developing EBT competency in supervision (James et al., 2008). This study improved upon existing research in this area by (a) randomly assigning participants to different supervision conditions, (b) examining the impact of training and supervision separately, and (c) using standardized simulated clients and rigorous observational methods to assess therapist behavior, rather than relying on self report (Watkins, 2014).

The Impact of Workshop Training on Knowledge, Beliefs, and Fidelity

Consistent with prior research examining the impact of EBT training (Beidas, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012; Cross et al., 2011; Dimeff et al., 2009), all participants showed increases in declarative knowledge of CBT for depression from pre-to post-workshop training. Participants’ attitudes towards evidence based practices likewise improved, dovetailing with previous research showing that trainings and courses that present EBTs can lead to more favorable attitudes among trainees (Bearman et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2011). Knowledge and attitudes are an important first step towards increasing the use of effective treatments, since both have been shown to correlate with greater reported use of EBTs by therapists (Kolko, Cohen, Mannarino, Baumann, & Knudsen, 2009; Nelson & Steele, 2007). However, other studies examining the impact of EBT training workshops have noted that while declarative knowledge about and attitudes towards EBTs improve, trainee behaviors are less likely to change (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). Indeed, one study found that therapists made limited gains in terms of treatment adherence following EBT training, even when that training involved experiential modeling and role-plays (Beidas et al., 2012). In the current study, participants showed considerable improvement from pre-to immediately post training in their level of cognitive restructuring fidelity, CBT expertise, and global CBT competence, but they did not approach proficiency on any of the three outcomes, as assessed during behavioral rehearsal with standardized simulated clients and rated by coders blind to study condition. Thus, workshop training in EBTs may be a necessary, but not sufficient, precursor for delivering EBTs with high fidelity.

The Impact of Supervision Practices on Treatment Fidelity

In contrast, the type of supervision received by study participants did differentially impact therapist behavior as assessed by the behavioral rehearsal with standardized clients. Specifically, those who received supervision that included skill modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback based on session review showed a pattern of incremental improvement across the three supervision meetings on cognitive restructuring fidelity, CBT expertise, and global CBT competence. These participants were rated as proficient or near proficient on all three outcomes by the final assessment. In contrast, the participants who were in the supervision condition that did not include skill modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback per session review did not improve following the assessment that occurred immediately post-training. In other words, for the latter group, supervision did not lead to any further gains in treatment fidelity above and beyond the improvements generated by the workshop training—improvements that did not result in proficient practice.

It is important to note that the two supervision conditions did not differ with regard to time spent in discussion of cognitive restructuring, but, consistent with the results of the Accurso et al. (2011) study, the SAU group spent the bulk of the supervision meetings in discussion of case conceptualization, therapeutic alliance, case management issues, and administrative tasks. The SUP+ group, in contrast, spent more time engaged in modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback. Participants in both conditions reported high levels of treatment satisfaction after each behavioral rehearsal, suggesting that both groups felt positively about the treatment they had delivered, regardless of objective ratings of the quality of that treatment.

Although the SUP+ group showed substantial improvement on all three fidelity outcomes over the course of the three supervision meetings, they did not reach optimal performance on any of these outcomes. The limited number of supervision sessions or the use of standardized clients to practice the newly learned therapeutic techniques may account for this effect. The standardized clients were trained to remain consistent in their responses and difficulty level. Bennett-Levy and colleagues (2009) theorize that the “when to” procedural system of therapist knowledge precedes a more advanced, third level—the “when-then” reflective system that permits flexibility to manage unexpected challenges in therapy, and that this reflective system results in true clinical expertise (pg. 573). Perhaps more challenging, and more varied, clinical experiences are needed to achieve this higher level of skill. Regardless, in this study even a limited amount of ongoing supervision that used active learning strategies allowed trainees to solidify concepts and techniques from the training in order to implement the practice proficiently in behavioral rehearsals.

It is possible that the dosage of active learning strategies utilized in supervision sessions might also be critical. Edmunds and colleagues (2013) examined the components of consultation sessions following training in CBT for youth anxiety disorders and did not find a significant relation between role-plays during telephone group consultation sessions and therapist adherence or skill. However, they noted that role-plays accounted for a minimal portion of time and that 72% of therapists participated in no role-plays. In the current study, a large percentage of time in the SUP+ supervision sessions was dedicated to supervisees observing skills modeled by the supervisor or engaging in role-plays as the therapist, and all participants received feedback from the supervisors. Therefore, similar to the importance of dosage of prescribed treatment elements in treatment sessions, the dosage of active learning strategies in supervision may be imperative for successful acquisition and subsequent implementation of EBTs in clinical practice.

Interestingly, an unspecified or “common factor” (Laska et al., 2014) of therapy improved for all participants over the course of the study, regardless of supervision condition. Coders rated the frequency and skillfulness of statements that affirmed or validated the client’s perspective, a practice theorized to contribute to client outcomes (Norcross & Wampold, 2011). Both supervision conditions showed improvements on this outcome. Without an assessment-only condition, it is impossible to know whether this change is related to the training, or reflect a practice effect of the standardized behavioral rehearsals. However, these results suggest that whereas therapist fidelity to model-specific practices may improve following particular supervision practices (modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback following session review), the development of common factors competencies may involve different processes.

Study Limitations

The current study represents an initial inroad into determining a causal relation between specific supervision processes and therapist EBT fidelity. We took care to address previous limitations in the literature, such as the lack of an experimental control group for supervision, the use of self-report rather than observational methods of assessing therapist behavior, and failing to distinguish the effects of workshop training and supervision. Nonetheless, the results should be considered in the context of several limitations. Perhaps most obviously, we used repeated behavioral rehearsals with standardized confederate clients rather than actual work samples in order to characterize therapist EBT fidelity. This can be best described as both a strength and a limitation of the study. As others have noted, using actual practice samples to assess fidelity poses numerous logistical challenges: (a) The need to consent clients receiving services, (b) the need to observe numerous sessions in order to find the requisite opportunity to use the particular skill being targeted (in this case, cognitive restructuring; Beidas et al., 2014), and (c) the potential for confounding relations among client severity and therapist competency performance. That is, when clients are fairly compliant and problems are less complex, therapists may have less opportunity to demonstrate the full repertoire of their skills—and are thus rated as less competent. In contrast, when clients are less engaged or have more complex problems, therapists may have the opportunity to use more varied and personalized skills, thus scoring higher in ratings of competence (Imel, Baer, Martino, Ball, & Carroll, 2011). This may, in part, explain inconsistent relations between therapist competence and client outcomes (Webb, DeRubeis, & Barber, 2010). By holding client severity constant, the current study assessed therapist fidelity to cognitive restructuring more systematically. Nonetheless, the extent to which therapist fidelity as exhibited with the standardized confederate clients would generalize to actual clients is not known for the current study. Research on another EBT skill, motivational interviewing, found medium-to-large correlations among therapist adherence with standardized clients and actual patients (Imel et al., 2014); future research should examine this question for the outcomes measured in the current study.

The participant population in this trial may also be a limitation, given that all participants were current students enrolled in professional mental health training programs. Because of the relatively small sample, participants were ineligible if they had prior experience delivering CBT or cognitive restructuring specifically. In the current study, internal validity was prioritized in order to maximize power to detect a causal relation between supervision practices and treatment fidelity. It will be important to replicate these results among a population of post-degree clinicians, who may vary more in terms of clinical experience and therefore the type of supervision that is most developmentally appropriate (Stoltenberg, McNeill, & Delworth, 1998). However, pre-internship training is a critical time to develop therapist skills (Bearman et al., 2015), and one aspect of clinical supervision should, in theory, be devoted to this formative purpose (Milne, 2009). This study suggests that model-specific supervision with active learning strategies and corrective feedback may be valuable for trainee skill development.

In the current study, the three-hour workshop training focused primarily on one discrete evidence-based practice (cognitive restructuring), and the behavioral rehearsals with standard confederate clients were likewise circumscribed. In reality, EBT workshops may often cover numerous practices that are embedded within a comprehensive treatment protocol (for example, CBT for youth depression may also include problem-solving skills, behavioral activation, and relaxation; Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009), and client presentation may demand the use of more than one practice element in a given session. Thus, we cannot be certain that the pattern of results found in this study would generalize if the training and the behavioral rehearsals targeted a more diverse set of skills. Future research should replicate this design with a broader range of therapeutic practices. A study that separately examined modeling, role-play, and corrective feedback as potential mediators of trainee outcomes would likewise further advance our understanding of potential mechanisms involved in trainee competency. We also had a brief number of supervision meetings, and no follow-up period after these meetings to determine the endurance of the effect of the SUP+ intervention.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite these limitations, this study provided a rigorous examination of the efficacy of active learning strategies in supervision on therapist fidelity to cognitive restructuring, a specific practice element found in many EBTs, as well as on CBT expertise and global CBT competence. This study, combined with past research in this area, provides support that modeling, role-plays, and corrective feedback following performance review may help to support the implementation of EBTs that more closely emulates the high-quality treatment provided in the efficacy RCTs that comprise the child and adolescent treatment evidence base. Future research efforts should replicate this experimental design in the context of an EBT effectiveness trial with practicing therapists in community clinics to determine whether these effects generalize to other therapist samples and improve client outcomes.

This research also has implications for the development of supervision guidelines by accrediting bodies, nearly all of which require supervised clinical hours to develop therapist practice but none of which specify the particular “micro skills” that should be used in trainee supervision (James et al., 2008). The supervision of graduate student trainees in particular might benefit from clear recommendations regarding the processes used to develop core clinical competencies (Cook et al., 2009). This study indicates that active learning strategies such as modeling, role-play, and corrective performance feedback may be essential processes that could increase not merely the use, but the effective and high quality delivery of EBTs for children and adolescents.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge with thanks the research funding received by Sarah Kate Bearman from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH083887) and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We are also grateful for the assistance of Adam Sales, Ph.D. and Daniel Swan, M.Ed. for their assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

This manuscript was presented at the annual convention of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies in November 2015, Chicago.

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Sarah Kate Bearman, Assistant Professor, The University of Texas at Austin, Department of Educational Psychology.

Robyn L. Schneiderman, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Department of School-Clinical Child Psychology, Yeshiva University

Emma Zoloth, Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, Department of School-Clinical Child Psychology, Yeshiva University.

References

- Accurso EC, Taylor RM, Garland AF. Evidence-based practices addressed in community-based children’s mental health clinical supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2011;5(2):88–96. doi: 10.1037/a0023537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Examiners in Clinical Social Work. Clinical Supervision: A Practice Specialty of Clinical Social Work. 2004 Oct; Retrieved April 9, 2015, from https://www.abecsw.org/images/ABESUPERV2205ed406.pdf.

- Association for Counselor Education and Supervision Taskforce on Best Practices in Clinical Supervision. Best practices in clinical supervision. 2011 Apr; Retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://www.acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/ACES-Best-Practices-in-clinicalsupervision document-FINAL.pdf.

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Herren J, Weisz JR. Therapist Adherence to Evidence Based Intervention – Observational Coding Manual. 2012 Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Wadkins M, Bailin A, Doctoroff G. Pre-practicum training in professional psychology to close the research-practice gap: Changing attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2015;9(1):13–20. doi: 10.1037/tep0000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Weisz JR, Chorpita B, Hoagwood K, Ward A, Ugueto A, Bernstein A. More practice, less preach? The role of supervision processes and therapist characteristics in EBP implementation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2013;40(6):518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0485-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Cross W, Dorsey S. Show me, don’t tell me: Behavioral rehearsal as a training and analogue fidelity tool. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(7):660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science And Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Levy J. Therapist skills: A cognitive model of their acquisition and refinement. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;34(1):57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Levy J, McManus F, Westling BE, Fennell M. Acquiring and refining CBT skills and competencies: Which training methods are perceived to be most effective? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;37(5):571–583. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809990270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager CF, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan C, Weisz JR. Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(5):677–681. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker KD, Nakamura BJ, Starace N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18(2):154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Park A, Tsai K, Korathu-Larson P, Higa-McMillan CK, Nakamura BJ The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Balancing Effectiveness With Responsiveness: Therapist Satisfaction Across Different Treatment Designs in the Child STEPs Randomized Effectiveness Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015 May 18; doi: 10.1037/a0039301. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. MATCH-ADTC: Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems. Satellite Beach, Florida: PracticeWise; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86(2):127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Schnurr PP, Biyanova T, Coyne JC. Apples don’t fall far from the tree: Influences on psychotherapists’ adoption and sustained use of new therapies. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(5):671–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WF, Seaburn D, Gibbs D, Schmeelk-Cone K, While AM, Caine ED. Does practice make perfect? A randomized control trial of behavioral rehearsal on suicide prevention gatekeeper skills. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2011;32(3–4):195–211. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Koerner K, Woodcock EA, Beadnell B, Brown MZ, Skutch JM, Harned MS. Which training method works best? A randomized controlled trial comparing three methods of training clinicians in dialectical behavior therapy skills. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(11):921–930. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds JM, Kendall PC, Ringle VA, Read KL, Brodman DM, Pimental SS, Beidas RS. An examination of behavioral rehearsal during consultation as a predictor of training outcomes. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(6):456–466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0490-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Cognitive restructuring of the disputing of irrational beliefs. In: O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, editors. General principles and empirically supported techniques of cognitive behavior therapy. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009. pp. 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Falender CA, Erickson Cornish JA, Goodyear R, Hatcher R, Kaslow NJ, Leventhal G, Grus C. Defining competencies in psychology supervision: A consensus statement. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(7):771–785. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad NA, Grus CL, Hatcher RL, Kaslow NJ, Hutchings PS, Madson MB, Crossman RE. Competency benchmarks: A model for understanding and measuring competence in professional psychology across training levels. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2009;3(4,Suppl):S5–S26. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzen M, Trask E, Fawley-King K. Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translating knowledge into action. Administration And Policy In Mental Health And Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(1):6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Liao JG, Letourneu EJ, Edwards DL. Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: The link between supervisory practices and therapist fidelity in MST programs. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(2):155–167. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Baer JS, Martino S, Ball SA, Carroll KM. Mutual influence in therapist competence and adherence to motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115(3):229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Baldwin SA, Baer JS, Hartzler B, Dunn C, Rosengren DB, Atkins DC. Evaluating therapist adherence in Motivational Interviewing by comparing performance with standardized and real patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(3):472–481. doi: 10.1037/a0036158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James IA, Milne D, Morse R. Microskills of clinical supervision: Scaffolding skills. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;22(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Borden KA, Collins FL, Forrest L, Illfelder-Kaye J, Nelson PD, Willmuth ME. Competencies conference: Future directions in education and credentialing in professional psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(7):699–712. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1984. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Baumann BL, Knudsen K. Community treatment of child sexual abuse: A survey of practitioners in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(1):37–49. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska KM, Gurman AS, Wampold BE. Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: A common factors perspective. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(4):467–481. doi: 10.1037/a0034332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N, Weisz JR. Manual for the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Competence Observational Measure of Performance with Youth Depression (CBTCOMP-YD) Cambridge, MA: manuscript, Department of Psychology, Harvard University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy RL, Rego SA. Cognitive restructuring. In: O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, O’Donohue WT, Fisher JE, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy: Core principles for practice. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2012. pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Southam-Gerow MA, Tully CB, Rodriguez A, Smith MM. Making a case for treatment integrity as a psychosocial treatment quality indicator for youth mental health care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2013;20(1):14–32. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne D. Evidence-based clinical supervision: Principles and practice. Leicester, England: Malden Blackwell Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Gleacher A, Beidas RS. Consultation as an implementation strategy for evidence-based practices across multiple contexts: Unpacking the black box. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2013;40(6):439–450. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Higa-McMillan CK, Okamura KH, Shimabukuro S. Knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence-based practices in community child mental health practitioners. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011;38(4):287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TD, Steele RG. Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34(4):319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, Wampold BE. Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. In: Norcross JC, Norcross JC, editors. Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness. 2nd. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NREPP: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. Retrieved August 15, 2014, from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/Index.aspx.

- R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rakovshik SG, McManus F. Establishing evidence-based training in cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of current empirical findings and theoretical guidance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(5):496–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AD, Pilling S, Turner J. Therapist training and supervision in clinical trials: Implications for clinical practice. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38(3):291–302. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Landsverk J, Stevens J The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. A survey of the infrastructure for children’s mental health services: Implications for the implementation of empirically supported treatments (ESTs) Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35(1–2):84–97. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, Southam-Gerow MA. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):32–43. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Mehta TG, Frazier SL, Shernoff ES. Clinical supervision in effectiveness and implementation research. Clinical Psychology: Science And Practice. 2013;20(1):44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Chapman JE. Clinical supervision in treatment transport: effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A. Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta- analysis of training studies. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/add.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Hinshaw SP. The second special issue on evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents: A 10-year update. Journal of Clinical Child And Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmans GI, Gatlin ET, McFall JP. The efficacy of evidence-based psychotherapies versus usual care for youths: Controlling confounds in a meta-reanalysis. Psychotherapy Research. 2010;20(2):234–246. doi: 10.1080/10503300903311293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg CD. Enhancing professional competence through developmental approaches to supervision. American Psychologist. 2005;60(8):857–864. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.8.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg CD, McNeill B, Delworth U. IDM supervision: An integrated developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins CE., Jr Clinical supervision in the 21st century: revisiting pressing needs and impressing possibilities. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2014;68(2):251–272. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2014.68.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CA, DeRubeis RJ, Barber JP. Therapist adherence/competence and treatment outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(2):200–211. doi: 10.1037/a0018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, Gibbons RD. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A Randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Hawley KM, Jensen-Doss A. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: A multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):750–761. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Ng MY, Bearman SK. Odd couple? Reenvisioning the relation between science and practice in the dissemination-implementation era. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(1):58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Richards K. The impact of clinical supervision on counsellors and therapists, their practice, and their clients. A systematic review of the literature. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2007;7(1):54–65. [Google Scholar]