The microbial oxidation of sulfide can produce large enrichments in the stable isotopes of sulfur.

Abstract

A sulfide-oxidizing microorganism, Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus (DA), generates a consistent enrichment of sulfur-34 (34S) in the produced sulfate of +12.5 per mil or greater. This observation challenges the general consensus that the microbial oxidation of sulfide does not result in large 34S enrichments and suggests that sedimentary sulfides and sulfates may be influenced by metabolic activity associated with sulfide oxidation. Since the DA-type sulfide oxidation pathway is ubiquitous in sediments, in the modern environment, and throughout Earth history, the enrichments and depletions in 34S in sediments may be the combined result of three microbial metabolisms: microbial sulfate reduction, the disproportionation of external sulfur intermediates, and microbial sulfide oxidation.

INTRODUCTION

Sulfide oxidation is a major part of the global microbial sulfur cycle. The metabolic pathways for the microbial oxidation of sulfide (MSO) are complex, likely exceed the currently known diversity (1), and may have evolved early in Earth’s history (2, 3). Despite its ubiquity on Earth today, the evidence for MSO in the rock record is sparse as it is generally considered to yield small sulfur isotope enrichments between the sulfide consumed and the sulfate produced (4). With this understanding, the appearance of large sulfur isotope partitioning observed between sulfate and sulfide in the environment, as well as in the geologic record, have been interpreted as being due to the rise of large sulfur isotope fractionation–inducing microbial processes, prominently microbial sulfate reduction (MSR) and microbial sulfur disproportionation (MSD) of intermediate inorganic sulfur species (5). On the basis of MSR and MSD being the major sulfur isotope fractionation–inducing processes in nature, a geobiological record of Earth’s early history has been drawn [e.g., (6–8)]. Here, with the model microorganism Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus (DA), it is shown that, in some instances, MSO produces larger sulfur isotope enrichments than previously measured and thus could be a third and hitherto underestimated source of notable sulfur isotope fractionation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

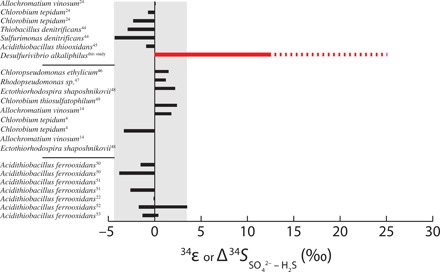

DA belongs to the family Desulfobulbaceae and is a haloalkaliphilic bacterium isolated from a hypersaline lake in the Egyptian-Libyan desert (9). DA grows by the oxidation of sulfide coupled to dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia. DA can also grow by disproportionation of intermediate sulfur compounds (9). When exponentially growing cells were transferred to a fresh medium at 30°C in the presence of excess sulfide and nitrate, replicate cultures of DA produced sulfur isotopic enrichments (denoted as εP/R; see Materials and Methods) in the sulfate of +13.1 ± 0.7 per mil (‰) and +12.0 ± 0.5‰ (Table 1). These growing conditions produced the largest sulfur isotope fractionation reliably measured by MSO and larger than the sulfur isotope fractionation produced by DA when growing by MSD (10). The large fractionation observed in cultures of DA cannot be attributed to concurrent MSR because of a lack of electron donors other than sulfide in the medium and the physiological inability of DA to grow by sulfate reduction (9) nor can they be attributed to MSD as a result of extracellular sulfide oxidation to intermediate sulfur species because alternative oxidants were not added to the medium. Strict anaerobic conditions were maintained during the experiments, and only low concentrations of sulfur intermediates were observed during the experiment (fig. S1). Throughout the experiments, DA consumed 1.41 to 1.45 times more sulfide than nitrate (Table 1). The electrons from sulfide that do not react with nitrate are diverted to the reduction of CO2 into organic matter resulting in carbon fixation rates [yield based on sulfide (Ys)] of 0.84 to 0.90 mol C (mol NO3−)−1. These Ys estimates are of similar magnitude to carbon fixation rates estimated from measurements of biomass accumulation and nitrate consumption [yield based on measurement of organic carbon (Yc)] of 0.20 to 0.39 mol C (mol NO3−)−1 (Table 1), which are comparable to dark carbon fixation in the environment (11), indicating that the electron budget fits with MSO being the only microbial metabolism in the experiments. Therefore, the large sulfur isotope fractionations measured with DA must involve MSO. For comparison, only small sulfur isotope fractionations (<5‰) by MSO have hitherto been reported (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Growth parameters and sulfur isotope effects during the growth of DA on sulfide and nitrate in three replicate experiments.

Substrate consumption ratios, yields, and cell-specific consumption rates highlight the differences in nitrate and sulfide consumption. Calculated 34ε values varied depending on whether the substrate (sulfide) or product (sulfate) was used. Uncertainty was propagated from regression uncertainties (see the Supplementary Materials).

| Experiment |

Growth rate (day−1) |

Substrate consumption ratio |

Yield estimates [mol C (mol NO3−)−1] |

Cell-specific consumption rates (fmol cell−1 day−1) |

Sulfur isotope enrichment factor* |

|||||||||

| k | σ | HS−:NO3− | σ | Ys | σ | Yc | σ | HS− | σ | NO3− | σ | 34ε | σ | |

| 1 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1.42 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 9.8 | 0.5 | 6.9 | 0.3 | +13.1 | 0.7 |

| 2 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 1.41 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 9.0 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 0.6 | ||

| 3 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 1.45 | 0.03 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 9.4 | 1.1 | 6.4 | 0.8 | +12.0 | 0.5 |

*34ε reported in this table is based on Rayleigh enrichment of the substrate pool. See Supplementary Materials and Materials and Methods.

Fig. 1. Compilation of 34ε or the difference between δ34S of sulfate and sulfide (Δ34SSO4−HS−) from this study (red bar), as well as those reported by previous studies (black bars) of microbial sulfide oxidizers that can oxidize sulfide to sulfate (table S1).

The solid bar for DA represents the average 34ε measured for cells growing in the exponential phase, whereas the broken line is when the maximum Δ34SSO4−HS− obtained when cells in stationary phase are transferred to fresh medium. The gray background outlines the range observed in past studies. When the product is enriched in 32S relative to the substrate, the values are negative, whereas when the product is enriched in 34S relative to the substrate, the values are positive. Only experiments with sulfide as substrate are included in this compilation.

The large sulfur isotope fractionations are best explained by a combination of mechanisms. First, a pH-dependent isotope effect can partially explain the observation with DA. It has been shown that the light [sulfur-32 (32S)] and heavy (34S) isotopes of sulfur quickly exchange between the two major sulfide species, dihydrogen sulfide (H2S) and monohydrogen sulfide (HS−), in the pH range of the experiment and reach an isotope equilibrium where H2S is +6‰ enriched relative to HS− (12, 13). Since MSO uses H2S as a substrate as opposed to HS− (14), the relative speciation of sulfide, which is pH dependent [pKa (where Ka is the acid dissociation constant) = 6.89], will have an important consequence on the resulting sulfur isotope enrichment. For example, at pH 7 where H2S accounts for 50% of the sulfide, phototrophic sulfide oxidizers consume H2S and produce elemental sulfur (S0). The H2S is +6‰ enriched in 34S relative to HS− but is only +3‰ enriched relative to the bulk sulfide. Thus, they produce S0, which is enriched in 34S relative to the bulk sulfide by +3‰ (14). Under the pH conditions of the DA experiments, (pH = 9.83) >99.9% of the sulfide is present as HS−, but the substrate used by the cell is likely to remain H2S because it can diffuse through lipid membranes while HS− does not (15–17), resulting in an enrichment in 34S of ~+6‰ over the isotopic composition of the bulk sulfide. The equilibrium isotope partitioning between H2S and HS− can thus account for about half of the magnitude of the sulfur isotope fractionation observed.

The large sulfur isotope fractionation in DA is also likely the result of steps downstream from the initial uptake of H2S. Sulfate-reducing bacteria belonging to the family Desulfobulbaceae oxidize H2S with oxygen or nitrate as electron acceptors, first oxidizing H2S to S0 followed, potentially, by a S0 disproportionation step (18). DA is also classified as a Desulfobulbaceae, and since candidate genes for the initial oxidation of sulfide, such as a type 1 sulfide:quinone reductase, an nrfA homolog or a dsrC that functions in reverse, are present and expressed both when DA was cultured under MSD and MSO conditions (19), the oxidation of H2S also likely proceeds via S0. Thus, DA produces S0 via oxidation of H2S coupled to dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia and thereby continuously provides the intracellular substrate for MSD that subsequently produces sulfide and sulfate. Consequently, dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia consumes the electrons released during oxidation of sulfide to S0. As phototrophic bacteria that oxidize H2S to S0 produce negligible sulfur isotope fractionation (4, 14), in DA, the other half of the observed sulfur isotope fractionation involves steps downstream of the initial oxidation to S0. Whereas phototrophic sulfide oxidizers consistently display an enrichment of 32S in the product during the oxidation of S0 to sulfate (4), DA produces an enrichment in 34S for this step. One important implication is that MSR capable of oxidizing sulfide (18) can potentially also produce large sulfur isotope fractionations during sulfide oxidation. Two possible pathways could result in the large isotope effect we observed during sulfide oxidation: intracellular disproportionation of the intermediate sulfur species to sulfide and sulfate or a reversal of the dissimilatory sulfate-reducing pathway.

Isotope fractionation during disproportionation can be high (20, 21). A disproportionation step, which results in the production of 34S-enriched sulfate and 32S-enriched sulfide (21), could explain the sulfur isotope enrichments because it is consistent with the observation in DA. When DA is grown by disproportionation on S0, the sulfur isotope fractionation is as high as +5.6‰ (10). When this effect is added up with the pH-dependent isotope effect associated with sulfide speciation in our culture conditions, they sum to about +12‰, consistent with the measurement for sulfide oxidation by DA. Moreover, the incorporation of an oxygen-18 (18O) label in the oxygen of sulfate produced by DA shows an enrichment of +20.1‰ over ambient water δ18O (fig. S6), which is of similar magnitude to MSD (+16 to 17‰) (22). This oxygen isotope signature distinguishes the pathway used by DA from the conventional sulfide oxidation pathways [typically expressing 18O enrichments in a range of 3 to 6‰ (23, 24)] and supports an alternative sulfide-oxidizing metabolism in DA. Yet, MSD is reported as being thermodynamically unfavorable at sulfide concentrations >1 mM (25) and typically requires the removal of sulfide for growth. However, the culture conditions have sulfide concentrations up to 10 mM where DA grows vigorously (fig. S1 to S3). Here, again, the alkaline environment must play an important role. As discussed earlier, H2S readily diffuses through cell membranes, but HS− does not, which, especially under alkaline conditions, can restrict sulfide supply into the cell (15–17). The pH of our growth medium results in H2S concentrations <12 μM, which is three orders of magnitude lower than the bulk sulfide concentration, and ensures an energy-yielding disproportionation step. Under lower pH, similar sulfide-oxidizing metabolisms may require lower bulk sulfide concentrations for growth because of the greater fraction of sulfide present as H2S.

An alternative to the oxidation and disproportionation pathway suggested above is that the sulfate reducing pathway, which is constitutive in DA, functions in reverse (19). For MSR, the large kinetic sulfur isotope fractionations of individual steps in the pathway can be masked by low reversibility in downstream steps, resulting in small sulfur isotope fractionations under favorable growth conditions (26, 27). A reversal of the sulfate-reducing pathway to oxidize sulfide opens the possibility of producing the entire range of sulfur isotope fractionation (from 0 to the thermodynamic equilibrium value of ≈+70‰ at 25°C), via sulfide oxidation. The main distinction is that the large kinetic sulfur isotope fractionations known for sulfate reduction are on the backward steps of the metabolic pathway. The fast substrate processing rates observed in the DA growth experiments (Table 1) are typical for pure cultures growing at high substrate consumption rates. Under conditions with lower substrate consumption rates, sulfur isotope fractionation could be further amplified, relative to the reported measurements (Table 1). In experiments with DA inoculated with cells from the stationary phase, which did not immediately grow exponentially upon transfer to fresh medium, sulfate with a δ34S value of up to +26‰ higher than the starting sulfide pool was measured (fig. S5). Therefore, in an environmental setting where substrate consumption rates are low, sulfur isotope fractionation could approach even the largest isotopic expressions of MSR and MSD metabolisms. The significance of the finding is that, in some environments, large sulfur isotope fractionations could perhaps result from MSO just as well as from MSR or MSD.

The δ34S of pyrite preserved in the geological record constitutes a cornerstone of our interpretation of Earth’s early biogeochemical history. Although current research indicates that sulfur isotopic composition of pyrite is predominantly affected by local processes [e.g., (28)], pyrite δ34S records have been debated. It is thought to reflect the appearance of sulfur metabolisms (6), the progressive oxygenation of the atmosphere (29, 30), dynamics of weathering on a global scale, and the corresponding changes in climate and oceanic chemistry (31). These interpretations are often hinged on an assumption that MSR and MSD are the only two metabolisms that can induce large sulfur isotope fractionations. Until now, large sulfur isotope fractionations, such as observed here during MSO, were not expected to have an important influence on the sulfur isotopic signatures preserved in the geologic record. The findings presented here puts this assumption into question because it means that large sulfur isotope fractionations can be generated directly in the oxidative part of the sulfur cycle, without requiring the accumulation of intermediate sulfur species. The next steps in assessing the contribution of high sulfur isotope fractionation during MSO to the geological record will require exploring the growing conditions and limits of the microorganisms that can carry out this process, as well as the preservation potential of local sedimentary environments.

High sulfur isotope fractionations during MSO may occur in close proximity to MSR in a loop of sulfur cycling, which would produce sulfate more enriched in 34S and sulfide more enriched in 32S than if MSR was the only significant sulfur isotope fractionating process. The presence of high sulfur isotope fractionations during MOS would then be recorded in the δ34S value of the pyrite preserved near the surface. Thus, in the geological record, the implication is that the contribution of the oxidative sulfur cycle may be larger than previously estimated [e.g., (32)] or it may be that it is erased by quantitative reoxidation of sulfide (33). Furthermore, DA is closely related to recently discovered sulfide oxidizers such as cable bacteria. DA and cable bacteria are both phylogenetically sulfate-reducing bacteria but are physiologically sulfide-oxidizing bacteria and may oxidize sulfide through the same pathway. Ecological surveys have shown that cable bacteria are widespread and thrive in sedimentary suboxic zones (19). Therefore, the oxidation pathway and the potential for large sulfur isotope fractionations may be globally important. This discovery suggests further investigations into the metabolic pathways of MSO, which induce large sulfur isotope fractionations, to obtain a comprehensive picture of the global sulfur cycle and the history of microbial life on Earth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation and sampling

Pure cultures of DA were grown at 30°C in a sodium carbonate/bicarbonate–buffered liquid mineral media with pH adjusted to about 9.8, as described in (9). Following sterilization, trace metal SL-10 solution (1 ml liter−1), selenite-tungstate solution (1 ml liter−1), and vitamin solution (10 ml liter−1) (34) were added to the medium in addition to sulfide, which was added as a 0.5 M solution of sodium sulfide and nitrate added as a 1 M solution of potassium nitrate. To minimize growth variability during the growth assays between replicate bottles, a large volume (2 liters) of medium was prepared anoxically to which the inoculum of DA was added. To recover an isotopically pure product sulfate, the carryover sulfate from the inoculum was minimized by centrifuging the cells for 10 min at 5000g, and the supernatant was replaced with fresh growth medium twice. This effectively removed all sulfate from the medium. Then, 100-ml serum bottles, which were sterile, crimp-sealed, and already flushed with N2:CO2 gas, were completely filled with the medium, leaving no headspace. All experiments were performed in the same medium under the same environmental conditions with the exception of the initial nitrate and sulfide concentrations, which varied between batches. Because sulfur isotope fractionation was under strong physiological control (35), in the three experiments that aimed at quantifying growth parameters and sulfur isotope fractionation (they were numbered 1 to 3; Table 1 and figs. S1 to S3), the same culture configuration was used; actively growing cells in the exponential phase were transferred to fresh medium three times without entering stationary phase before innoculating the assay bottles. Experiments using cells in stationary phase were labeled A to D and reported in figs. S5 and S6. In these experiments, the same medium was spiked with 18O-labeled water resulting in different δ18OH2O, from A to D, to investigate the pathway of sulfide oxidation.

In all experiments, sampling consisted of sacrificing a single vial by taking it out of the incubator, removing the crimp seal and quickly recovering aliquots for each analysis. One milliliter was taken, vigorously bubbled with humidified CO2 gas to remove sulfide, and stored at 4°C until analysis by ion chromatography, as elaborated in (36) for sulfate and nitrate concentrations. One milliliter of sample was also quantitatively added to 0.5 ml of 5% zinc acetate solution and frozen for sulfide concentration. One milliliter was taken and immediately frozen for ammonium measurement. Thiosulfate and sulfite were quantified by sampling 0.5 ml of medium followed by derivitization by monobromobimane following the procedure outlined in (37) and freezing at −80°C until analysis a week later. Last, 30 ml was transferred to a 50-ml falcon tube with 20 ml of a 5% zinc acetate solution and frozen for isotope analysis.

Specific growth

Specific growth rates (k day−1) of exponentially growing cells were calculated as

| (1) |

where C is the cell concentration (in cells ml−1) and t is the time of the sampling (in days). We estimated cell concentrations by measuring the optical density (OD) of an actively growing culture at 600 nm. Each OD measurement was performed in triplicate. The OD measurements were converted to cell concentrations via a constant conversion factor (11.4 × 108) obtained by counting individual cells in dilute, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole–stained aliquots with an epifluorescence microscope.

Determinations of yields [Y, in 106 cells per μmol substrate consumed; Yc, in mol C (mol substrate)−1] and cell-specific sulfide oxidation rates (csSOR, in femtomoles HS− consumed per cell per day) were based on concentrations of sulfate produced by exponentially growing cultures. Sulfate and nitrate were measured simultaneously by ion chromatography on a Dionex system using an AG-18/AS-18 column (250-mm Thermo Scientific Dionex IonPac) with a KOH eluent. To achieve good separation of sulfate from chloride, eluent concentrations were kept at 12 mmol KOH liter−1 until the sulfate peak eluted. Then, eluent concentration was increased to 30 mmol KOH liter−1 to flush the column of strongly binding ions. HS− and NH4+ concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically at wavelengths of 672 and 640 nm, using the protocols of (38, 39), respectively. Once substrates, products, and cell numbers were measured, we estimated yield during exponential growth. We calculated molar yield of carbon in two ways. First, we assumed that the discrepancy between the consumption of sulfide and nitrate according Eq. 1 was due to the electrons being diverted to CO2 fixation (Eq. 2). We calculated this estimate of yield based on sulfide (Ys) as

| (2) |

where mHS is the number of moles of HS− per ml and mNO3 is the number of moles of NO3− per ml. The multiplication factor is to convert from moles of excess sulfide to organic matter according to a 1:2 stoichiometry. The units of Ys are mol C (mol NO3−)−1. This expression is supported by a 1-to-1 stoichiometry between HS− or NO3− consumed and SO42− or NH4+ produced (figs. S1 to S3). Given that the sulfate and nitrate results had the highest precision, these were used in the calculations. Second, the Yc was calculated as

| (3) |

where mc is the moles of organic carbon in the growth experiment calculated from measurements of total organic carbon and OD. The units of Yc are mol C (mol NO3−)−1. The csSOR and cell-specific nitrate reduction rate (csNRR) during exponential growth was calculated from estimates of growth rate and yield as

| (4) |

| (5) |

where the factor of 1015 adjusts the units of csSOR and csNRR to femtomoles HS− or NO3− per cell per day. Uncertainty on growth results was reported as the SD on the slope of a linear regression or propagation from these regressions.

Measurement of sulfur isotope enrichments

The microbial cultivation samples were analyzed for sulfur isotopes following the method described in (40). Sulfur isotopic ratios were reported as

| (6) |

where 34R = 34S/32S and V-CDT refers to the Vienna-Canyon Diablo Troilite international reference scale. The uncertainty on δ34SSO4 was determined using the SD of the standard NBS 127 at the beginning and the end of each run (less than 0.3‰, 1σ). Measurements of δ34SSO4 and δ34SH2S were calibrated according to the following standards: NBS 127, IAEA-SO-6, IAEA-SO-5, IAEA-S-2, IAEA-S3, and an in-house silver sulfide standard with δ34SSO4 of 20.3, −34.1, 0.5, 22.3, −34.3, and 3.4‰, respectively. δ34S is reported with respect to V-CDT. The measurement of sulfur isotope fractionation factor during sulfide oxidation was estimated as the regression of δ34S versus −ln(f) for the reactant (41)

| (7) |

where δR is the measured isotopic composition of the reactant sulfide, δR0 is the initial isotopic composition of the reactant sulfide, f is the fraction of reactant consumed over the initial amount of reactant, and εP/R is the sulfur isotope fractionation factor between the reactant, R, and the product, P. The sulfur isotope fractionation was also estimated using the regression of the product on a plot of δ34S versus [f/(1 − f)]ln(f) (41)

| (8) |

where δp is the measured isotopic composition of the product sulfate and also provides an estimate of the fractionation factor. Uncertainty on εP/R is reported as the SD on the linear regressions. In the experiments with cells from the stationary phase (A to D), specific fractionation factors were reported with regard to the maximum difference between the δ34S of sulfate and that of sulfide.

Oxygen isotope

For oxygen isotopes, values of isotopic ratios were reported as

| (9) |

where 18R = 18O/16O and V-SMOW refers to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water international reference scale. Samples for δ18OSO4 were run in triplicates, and the SD of these triplicate analyses was used as the error (~0.3‰, 1σ). Measurements of δ18OSO4 were calibrated according to the following standards: NBS 127, IAEA-SO-6, and IAEA-SO-5 with δ18OSO4 of 8.6, −11.35, and 12.1‰, respectively. δ18OH2O values were measured by a continuous flow gas source isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) coupled to a GasBench II interface. Samples were corrected to NBS 127. The uncertainty on the measurement was ±0.1‰. δ18OH2O was reported versus Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW). The equilibrium value of δ18OSO4 was calculated by correcting for the small concentration of sulfate carried over with the inoculum according to

| (10) |

where δ18Ot is the value of the sulfate at the time of sampling, δ18Oeq is the value of the sulfate synthesized by sulfide oxidation, δ18Oin is the value of the sulfate carried over with the inoculum, and x is the fraction of the sulfate, which is part of the inoculum in a given sample t.

S0, sulfite, and thiosulfate analysis

S0 (consisting of soluble, nanoparticulate, and polysulfide-bound sulfur) was extracted in toluene following the method described in (42). To extract all zerovalent sulfur, the samples were first acidified to pH = 7, and sulfide was fixed as ZnS before the extraction. S0 was quantified after extraction, and dilution with methanol (3:1 methanol to sample) by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a C18 column and a methanol/water mixture (98% MeOH) as the eluent. Thiosulfate and sulfite were quantified by HPLC using a C18 column following derivatization by monobromobimane (37). The method detection limit for both S2O32− and SO32− is 0.005 μM.

Total organic carbon analysis

Twelve-milliliter samples of actively growing DA cultures were acidified with a 5 ml of a 0.1 M HCl solution and centrifuged at 5000g for 10 min, rinsed with deionized water, dried, and packed into tin capsules for analysis on an elemental analyzer for total organic carbon content.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Michaud and B. Wing for insightful discussions, K. B. Oest for technical assistance, and G. Dickens and two anonymous reviewers for constructive criticism, which improved the manuscript. Funding: This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF104), the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-7014-00196), and the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant 294200). A.J.F. acknowledges a Marie-Curie European Fellowship (SedSulphOx, MSCA 746872). P.W.C. acknowledges an Agouron Institute Fellowship. Author contributions: Conceptualization: A.P., G.A., and K.F.; formal analysis: A.P., G.A., A.J.F., and S.A.H.; funding acquisition: B.B.J. and K.F.; investigation: A.P. and S.A.H.; methodology: A.P. and G.A.; supervision: B.B.J. and K.F.; validation: A.P.; writing (original draft): A.P.; and writing (review and editing): A.P., G.A., A.J.F., P.W.C., A.V.T., B.B.J., and K.F. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaaw1480/DC1

Fig. S1. Growth experiment 1.

Fig. S2. Growth experiment 2.

Fig. S3. Growth experiment 3.

Fig. S4. Plot of δ34S as a function of ln(f) for the sulfide or [f/(1 − f)]ln(f) for the sulfate for experiments 1 and 3 (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. S5. Plot of δ34S as a function of the sulfide consumed (f).

Fig. S6. Water (black bars) and equilibrium sulfate (gray bars) δ18O in respective water enrichment experiments A to D.

Table S1. Compilation of sulfur isotope enrichments during MSO used for the construction of Fig. 1 and additional information on growth conditions.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Wasmund K., Mußmann M., Loy A., The life sulfuric: Microbial ecology of sulfur cycling in marine sediments. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 9, 323–344 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wacey D., McLoughlin N., Whitehouse M. J., Kilburn M. R., Two coexisting sulfur metabolisms in a ca. 3400 Ma sandstone. Geology 38, 1115–1118 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czaja A. D., Beukes N. J., Osterhout J. T., Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria prior to the Great Oxidation Event from the 2.52 Ga Gamohaan Formation of South Africa. Geology 44, 983–986 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerkle A. L., Farquhar J., Johnston D. T., Cox R. P., Canfield D. E., Fractionation of multiple sulfur isotopes during phototrophic oxidation of sulfide and elemental sulfur by a green sulfur bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 291–306 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen Y., Buick R., The antiquity of microbial sulfate reduction. Earth Sci. Rev. 64, 243–272 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen Y., Buick R., Canfield D. E., Isotopic evidence for microbial sulphate reduction in the early Archaean era. Nature 410, 77–81 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sim M. S., Bosak T., Ono S., Large sulfur isotope fractionation does not require disproportionation. Science 333, 74–77 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunzmann M., Bui T. H., Crockford P. W., Halverson G. P., Scott C., Lyons T. W., Wing B. A., Bacterial sulfur disproportionation constrains timing of Neoproterozoic oxygenation. Geology 45, 207–210 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorokin D. Y., Tourova T. P., Mußmann M., Muyzer G., Dethiobacter alkaliphilus gen. nov. sp. nov., and Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus gen. nov. sp. nov.: two novel representatives of reductive sulfur cycle from soda lakes. Extremophiles 12, 431–439 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poser A., Vogt C., Knöller K., Sorokin D. Y., Finster K. W., Richnow H.-H., Sulfur and oxygen isotope fractionation during bacterial sulfur disproportionation under anaerobic haloalkaline conditions. Geomicrobiol J. 33, 934–941 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boschker H. T. S., Vasquez-Cardenas D., Bolhuis H., Moerdijk-Poortvliet T. W. C., Moodley L., Chemoautotrophic carbon fixation rates and active bacterial communities in intertidal marine sediments. PLOS ONE 9, e101443 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tudge A. P., Thode H. G., Thermodynamic properties of isotopic compounds of sulphur. Can. J. Res. 28b, 567–578 (1950). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otake T., Lasaga A. C., Ohmoto H., Ab initio calculations for equilibrium fractionations in multiple sulfur isotope systems. Chem. Geol. 249, 357–376 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry B., Gest H., Hayes J. M., Isotope effects associated with the anaerobic oxidation of sulfide by the purple photosynthetic bacterium, Chromatium vinosum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 22, 283–287 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathai J. C., Missner A., Kügler P., Saparov S. M., Zeidel M. L., Lee J. K., Pohl P., No facilitator required for membrane transport of hydrogen sulfide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16633–16638 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riahi S., Rowley C. N., Why can hydrogen sulfide permeate cell membranes? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15111–15113 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuevasanta E., Denicola A., Alvarez B., Möller M. N., Solubility and permeation of hydrogen sulfide in lipid membranes. PLOS ONE 7, e34562 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuseler K., Krekeler D., Sydow U., Cypionka H., A common pathway of sulfide oxidation by sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 144, 129–134 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorup C., Schramm A., Findlay A. J., Finster K. W., Schreiber L., Disguised as a sulfate reducer: Growth of the deltaproteobacterium Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus by sulfide oxidation with nitrate. MBio 8, e00671-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habicht K. S., Canfield D. E., Rethmeier J., Sulfur isotope fractionation during bacterial reduction and disproportionation of thiosulfate and sulfite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 62, 2585–2595 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böttcher M. E., Thamdrup B., Vennemann T. W., Oxygen and sulfur isotope fractionation during anaerobic bacterial disproportionation of elemental sulfur. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 1601–1609 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böttcher M. E., Thamdrup B., Anaerobic sulfide oxidation and stable isotope fractionation associated with bacterial sulfur disproportionation in the presence of MnO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 1573–1581 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balci N., Shanks W. C. III, Mayer B., Mandernack K. W., Oxygen and sulfur isotope systematics of sulfate produced by bacterial and abiotic oxidation of pyrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 3796–3811 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brabec M. Y., Lyons T. W., Mandernack K. W., Oxygen and sulfur isotope fractionation during sulfide oxidation by anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 83, 234–251 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finster K., Microbiological disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds. J. Sulphur Chem. 29, 281–292 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rees C. E., A steady-state model for sulphur isotope fractionation in bacterial reduction processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 37, 1141–1162 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wing B. A., Halevy I., Intracellular metabolite levels shape sulfur isotope fractionation during microbial sulfate respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 18116–18125 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasquier V., Sansjofre P., Rabineau M., Revillon S., Houghton J., Fike D. A., Pyrite sulfur isotopes reveal glacial−interglacial environmental changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 5941–5945 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canfield D. E., The early history of atmospheric oxygen: Homage to Robert M. Garrels. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 1–36 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berner R. A., GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5653–5664 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paytan A., Kastner M., Campbell D., Thiemens M. H., Sulfur isotopic composition of cenozoic seawater sulfate. Science 282, 1459–1462 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Habicht K. S., Canfield D. E., Sulphur isotope fractionation in modern microbial mats and the evolution of the sulphur cycle. Nature 382, 342–343 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fike D. A., Finke N., Zha J., Blake G., Hoehler T. M., Orphan V. J., The effect of sulfate concentration on (sub)millimeter-scale sulfide δ34S in hypersaline cyanobacterial mats over the diurnal cycle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6187–6204 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 34.F. Widdel, F. Bak, Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria, in The Prokaryotes, A. Balows, H. G. Trüper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, K.-H. Schleifer, Eds. (Springer, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pellerin A., Wenk C. B., Halevy I., Wing B. A., Sulfur isotope fractionation by sulfate-reducing microbes can reflect past physiology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4013–4022 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellerin A., Antler G., Røy H., Findlay A., Beulig F., Scholze C., Turchyn A. V., Jørgensen B. B., The sulfur cycle below the sulfate-methane transition of marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 239, 74–89 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zopfi J., Ferdelman T. G., Fossing H., Distribution and fate of sulfur intermediates—Sulfite, tetrathionate, thiosulfate, and elemental sulfur—In marine sediments. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 379, 97–116 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cline J. D., Spectrophtometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14, 454–458 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bower C. E., Holm-Hansen T., A salicylate–hypochlorite method for determining ammonia in seawater. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37, 794–798 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antler G., Turchyn A. V., Herut B., Davies A., Rennie V. C. F., Sivan O., Sulfur and oxygen isotope tracing of sulfate driven anaerobic methane oxidation in estuarine sediments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 142, 4–11 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariotti A., Germon J. C., Hubert P., Kaiser P., Letolle R., Tardieux A., Tardieux P., Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: Some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes. Plant Soil 62, 413–430 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Findlay A. J., Gartman A., MacDonald D. J., Hanson T. E., Shaw T. J., Luther G. W. III, Distribution and size fractionation of elemental sulfur in aqueous environments: The Chesapeake Bay and Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 142, 334–348 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaplan I. R., Rittenberg S. C., Microbiological fractionation of sulphur isotopes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 34, 195–212 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poser A., Vogt C., Knöller K., Ahlheim J., Weiss H., Kleinsteuber S., Richnow H.-H., Stable sulfur and oxygen isotope fractionation of anoxic sulfide oxidation by two different enzymatic pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9094–9102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaplan I. R., Rafter T. A., Fractionation of stable isotopes of sulfur by thiobacilli. Science 127, 517–518 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mekhtieva V. L., Kondrat'eva E. N., Fractionation of stable isotopes of sulfur by photosynthesizing purple sulfur bacteria Rhodopseudomonas sp. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 166, 465–468 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondrat'eva E. N., Mekhtieva V. L., Sumarokova R. S., Concerning the directionality of the isotope effect in the first steps of sulphide oxidation by purple bacteria. Vest. Mosk. Univ. Ser. VI VI, 45–48 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivanov M. V., Gogotova G. I., Matrosov A. G., Ziakun A. M., Fractionation of sulfur isotopes by phototrophic sulfur bacterium Ectothiorhodospira shaposhnikovii. Mikrobiologiia 45, 757–762 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chambers L. A., Trudinger P. A., Microbiological fractionation of stable sulfur isotopes: A review and critique. Geomicrobiol J. 1, 249–293 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thurston R. S., Mandernack K. W., Shanks W. C. III, Laboratory chalcopyrite oxidation by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans: Oxygen and sulfur isotope fractionation. Chem. Geol. 269, 252–261 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balci N., Mayer B., Shanks W. C. III, Mandernack K. W., Oxygen and sulfur isotope systematics of sulfate produced during abiotic and bacterial oxidation of sphalerite and elemental sulfur. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 77, 335–351 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunner B., Yu J.-Y., Mielke R. E., MacAskill J. A., Madzunkov S., McGenity T. J., Coleman M., Different isotope and chemical patterns of pyrite oxidation related to lag and exponential growth phases of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans reveal a microbial growth strategy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 270, 63–72 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pisapia C., Chaussidon M., Mustin C., Humbert B., O and S isotopic composition of dissolved and attached oxidation products of pyrite by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans: Comparison with abiotic oxidations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 2474–2490 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/7/eaaw1480/DC1

Fig. S1. Growth experiment 1.

Fig. S2. Growth experiment 2.

Fig. S3. Growth experiment 3.

Fig. S4. Plot of δ34S as a function of ln(f) for the sulfide or [f/(1 − f)]ln(f) for the sulfate for experiments 1 and 3 (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. S5. Plot of δ34S as a function of the sulfide consumed (f).

Fig. S6. Water (black bars) and equilibrium sulfate (gray bars) δ18O in respective water enrichment experiments A to D.

Table S1. Compilation of sulfur isotope enrichments during MSO used for the construction of Fig. 1 and additional information on growth conditions.