Abstract

Abdominal pain can be an important symptom in some patients with gastroparesis (Gp).

Aims:

1) Describe characteristics of abdominal pain in Gp; 2) Describe Gp patients reporting abdominal pain.

Methods:

Patients with idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) and diabetic gastroparesis (DG) were studied with gastric emptying scintigraphy, water load test, wireless motility capsule, and questionnaires assessing symptoms (Patient Assessment of Upper GI Symptoms [PAGI-SYM] including Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index [GCSI]), quality of life (PAGI-QOL, SF-36), psychological state (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], State Trait Anxiety Index [STAI], PHQ-15 somatization scale).

Results:

346 Gp patients included 212 IG and 134 DG. 90% of Gp patients reported abdominal pain (89% DG and 91% IG). Pain was primarily in upper or central midline abdomen; described as cramping or sickening. Upper abdominal pain was severe or very severe on PAGI-SYM by 116/346 (34%) patients, more often by females than males, but similarly in IG and DG. Increased upper abdominal pain severity was associated with increased severity of the nine GCSI symptoms, depression on BDI, anxiety on STAI, somatization on PHQ-15, use of opiate medications, decreased SF-36 physical component and PAGI-QOL, but not related to severity of delayed gastric emptying or water load ingestion. Using logistic regression, severe/very severe upper abdominal pain associated with increased GCSI scores, opiate medication use, and PHQ-15 somatic symptom scores.

Conclusions:

Abdominal pain is common in patients with Gp, both IG and DG. Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain occurred in 34% of Gp patients and associated with other Gp symptoms, somatization, and opiate medication use.

Keywords: gastroparesis, abdominal pain, diabetic gastroparesis, idiopathic gastroparesis

Introduction

Nausea, vomiting, early satiety, postprandial fullness are classic symptoms of gastroparesis (1,2). Abdominal pain is also reported by many patients with gastroparesis, but is often classified as an atypical symptom or not recognized as a symptom of gastroparesis (3). In some patients with gastroparesis, abdominal pain can be a prominent component of their symptoms (4).

Despite several reports on the high prevalence of abdominal pain in gastroparesis (4,5,6), abdominal pain is not well characterized in patients with gastroparesis; nor are the gastroparesis patients with abdominal pain well described. The first National Institute of Health (NIH) gastroparesis registry study identified abdominal pain being the predominant symptom in one fifth of patients with gastroparesis (4). Moderate-severe abdominal pain was prevalent in gastroparesis, impaired quality of life, and was associated with idiopathic etiology, lack of infectious prodrome, and opiate use. Abdominal pain as the predominant symptom had a similar impact on disease severity and quality of life as predominant nausea/vomiting.

The primary aims of this study were to: 1) describe the characteristics of abdominal pain in gastroparesis; and 2) describe the gastroparesis patients that report abdominal pain. In addition, we aimed to: 3) determine the association of abdominal pain in gastroparesis with other pain-related conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraine headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis; 4) determine the effect of abdominal pain in gastroparesis on quality of life; 5) determine if the abdominal pain correlates with an increase in somatization, anxiety, and depression; and 6) determine if abdominal pain is associated with gastric emptying. We had the following hypotheses for this study: 1) There are differences in the severity and characteristics of abdominal pain in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis with abdominal pain more severe in patients with idiopathic than diabetic gastroparesis. 2) Abdominal pain in gastroparesis is associated with other pain-related conditions. 3) Abdominal pain is an important factor in the health care utilization of patients with gastroparesis and associates with their impaired quality of life. 4) Abdominal pain in gastroparesis correlates with an increase in somatization and anxiety. 5) Abdominal pain is not associated with delayed gastric emptying.

Methods

The Gastroparesis Registry 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01696747) was implemented as an observational study of patients with gastroparesis enrolled prospectively (7,8). We hoped to gain greater insight into the characteristics of abdominal pain in gastroparesis then in our first report (4) by improving the assessment of abdominal pain and physiologic testing in the second NIH gastroparesis registry. The clinical characteristics of abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis are more thoroughly described with the use of special questionnaires developed to assess the characteristics of abdominal pain as well as using several questionnaires on pain including the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Symptom (PAGI-SYM) questionnaire for gastroparesis (9) and others commonly used in the pain field - Brief Pain Inventory (10) and McGill Pain Inventory (11).

Gastroparetic patients of diabetic, idiopathic, and postfundoplication etiologies were enrolled at seven centers from September 2012 to January 2018. Patients had symptoms of gastroparesis for >12 weeks, delayed gastric emptying, and negative endoscopy. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each Clinical Center and Data Coordinating Center. This report focuses on patients with either idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) or diabetic gastroparesis (DG). There were too few patients with postfundoplication gastroparesis (20) to analyze. The diabetic patients could have either Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) as defined by the physician. The diagnosis of patients with the idiopathic etiology was based on no previous gastric surgery, no diabetes history, a normal hemoglobin A1C, and no other known etiologies.

Study Protocol

During interviews with subjects, the study physicians or coordinators completed case report forms including data on gastroparesis disease onset, symptoms, disease profile, prior surgeries, associated medical conditions, and medication and supplemental therapies. The study physicians performed a comprehensive physical examination. Laboratory measures were obtained, including hemoglobin A1C value, CRP, and ESR levels.

The clinical severity of gastroparesis was assessed using a previously described scale (12) in which the severity was graded as grade 1: mild gastroparesis (symptoms relatively easily controlled and able to maintain weight and nutrition on a regular diet); grade 2: compensated gastroparesis (moderate symptoms with only partial control with use of daily medications, able to maintain nutrition with dietary adjustments); grade 3: gastroparesis with gastric failure (refractory symptoms that are not controlled as shown by the patient having ER visits, frequent doctor visits or hospitalizations and/or inability to maintain nutrition via an oral route).

The 20 item Patient Assessment of Upper GI Symptoms (PAGI-SYM) questionnaire assesses symptoms of gastroparesis, dyspepsia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (9); it includes the 9 symptoms of Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) (3). Total GCSI score equals mean of the nausea/vomiting subscore, postprandial fullness/early satiety subscore, and bloating subscore where: Nausea/vomiting subscore=mean of scores for nausea, retching, and vomiting; Postprandial fullness/early satiety sub-score=mean of scores for stomach fullness, inability to finish meal, excessive fullness, and loss of appetite; and Bloating subscore=mean of scores for bloating and large stomach. Upper abdominal pain subscore was average of upper abdominal pain and upper abdominal discomfort. Patients are asked to assess the severity of their symptoms during the previous two weeks using a 0 to 5 scale where no symptoms=0, very mild=1, mild=2, moderate=3, severe=4, and very severe=5.

Disease-specific quality of life was assessed by the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders Quality of Life (PAGI-QOL) survey, which scores 30 factors from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time) (13). Patients were asked how often gastrointestinal problems they may be experiencing have affected different aspects of their quality of life and well-being in the past two weeks. Overall PAGI-QOL scores were calculated by taking means of subscores after reversing item scores; thus, a mean PAGI-QOL score of 0 represents poor quality of life while 5 reflects the best life quality.

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) was additionally used to assess the patients’ views of overall physical and mental health in the past 4 weeks (14). The 8 subscales were standardized to the 1998 U.S. general population with a mean (±SD) of 50±10. Physical and mental health summary measures were computed. A higher score reflects higher quality of life.

Psychological functioning was assessed. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-question multiple-choice questionnaire to quantify depression (15). Each answer is scored on a scale of 0 to 3. Higher total scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms with 29–63 indicating severe depression. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) consists of 20 questions relating to state anxiety (a temporary or emotional state) and 20 questions pertaining to trait anxiety (long standing personality trait anxiety with a general propensity to be anxious) (16). A score of ≥50 denotes significant anxiety. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15) is a questionnaire that is useful in screening for somatization and in monitoring somatic symptom severity (17,18). From this, the PHQ-12 was calculated, removing the three GI symptoms (19).

The McGill Pain Questionnaire allows individuals to provide a description of the quality and intensity of pain that they are experiencing (11). This questionnaire consists primarily of 3 major classes of word descriptors--sensory, affective and evaluative--that are used by patients to specify subjective pain experience. It also contains an intensity scale and other items to determine properties of pain experience.

The Brief Pain Inventory - Short Form (BPI-sf) is a 9 item questionnaire used to evaluate the severity of a patient’s pain and the impact of this pain on the patient’s daily functioning (10,20). The patient rates their worst, least, average, and current pain intensity, list current treatments and their perceived effectiveness, and rates the degree that pain interferes with general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other persons, sleep, and enjoyment of life on a 10 point scale.

A GpCRC Abdominal Pain questionnaire was designed to assess the clinical characteristics of abdominal pain (6). Questions were generated to assess location of pain, timing of pain and the characteristics of abdominal pain. This questionnaire also contains components about chronic and acute episodes of abdominal pain modified from the IBS pain questionnaire of Spiegel et al (21).

Gastric Emptying Scintigraphy

Patients were instructed to stop medications that could affect GI motility for 72 hours prior to the study and to come to the Nuclear Medicine Section in the morning after fasting overnight. Diabetic patients had glucose levels checked to ensure <270 mg/dL. Gastric emptying scintigraphy was performed using a standard low-fat, Eggbeaters® meal to measure solid emptying (22,23). The meal consisted of the equivalent of two large eggs radiolabeled with Tc-99m sulfur colloid served with two pieces of white bread and jelly. In addition, patients were given 120 ml water radiolabeled with Indium-111 DTPA (diethylene triamine pentacetic acid) for measurement of liquid gastric emptying (24). Following ingestion of the meal, imaging was performed at 0, 1, 2 and 4 hrs with patient upright for measuring gastric emptying of Tc-labeled solids and 111-In-labeled liquids.

Gastric emptying was analyzed as the percent of radioactivity retained in the stomach over time using the geometric center of the decay-corrected anterior and posterior counts for each time point. Gastric retention of Tc-99m >60 % at 2 hrs and/or >10% at 4 hrs was considered evidence of delayed gastric emptying of solids. Delayed gastric emptying of liquids in the presence of solids is greater than 50% retention of In-111 at 1 hr emptying (24).

Water Load Satiety Testing (WLST)

A satiety test of non-caloric liquid water was performed. The WLST is a standardized test to induce gastric distension and to evoke gastric motility responses without the complex hormonal response of a caloric test meal. On the day of testing, patients reported after fasting overnight and were instructed to drink maximal volumes of water using an opaque 150 mL cup over 5 minutes until they felt completely full (25). The volume of water consumed was recorded.

Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC)

WMC was used to assess regional GI transit (26). Patients stopped gastric acid suppressant medications for 1 week and medications that could affect GI motility for 72 hours prior to the study. Patients fasted overnight before testing. Diabetic patients had glucose levels checked to ensure <270 mg/dL. Patients ingested one SmartBar® (Medtronic) (255 kcal, 66% carbohydrate, 17% protein, 2% fat, 3% fiber) over 10 minutes with ≤50 mL water. The WMC was then swallowed with 50 mL of water. Patients fasted for another 6 hours after WMC ingestion and then resumed normal diets. Patients returned the data receiver after 4-days. Gastric emptying times (GET) were calculated from the time of WMC ingestion to when the capsule passed into the duodenum, as defined by abrupt ≥2 pH unit increases from the lowest postprandial value to levels ≥4 that persisted for at least 10 minutes (26).

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics, including demographics, clinical features, medication use, gastroparesis severity measures, gastric emptying, quality of life, and psychological measures were compared for those with different degrees of upper abdominal pain, with groupings of none/mild vs. moderate vs. severe/very severe upper abdominal pain, as measured by the PAGI-SYM. Items from the GpCRC Abdominal Pain Questionnaire, which included items on location, severity, and frequency of abdominal pain, whether or not the pain worsens or improves with eating, worsens at night or interferes with sleep, and the presence, severity, and frequency of acute episodes of abdominal pain, were compared for those with diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Similar analyses were performed for the Brief Pain Inventory, and for measures of chronic and acute abdominal pain. Data are presented as mean±SD or N (%) and p-values determined by Fisher’s exact test for categorical measures and by ANOVA for continuous measures (27). Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine baseline characteristics associated with three outcomes (28): 1) PAGI-SYM severe/very severe vs. none/mild/moderate upper abdominal pain; 2) abdominal pain characterized as horrible or excruciating vs. not on the GpCRC Abdominal Pain Questionnaire; and 3) Brief Pain Inventory score ≥8 vs. <8. Final models of baseline predictors were determined from multiple logistic regressions of the outcomes on a candidate set of baseline predictors that resulted in the best model determined by the minimum Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) (29). Candidate set of baseline characteristics included age, diabetes status, gastroparesis etiology, acute vs. insidious symptom onset, presence of initial infectious prodrome, hospitalization for gastroparesis in year prior to enrollment, 2-hour and 4-hour gastric emptying retention (%), GCSI, PAGI-QOL, SF-36 physical and mental scores, PHQ-15 somatic symptom score, Beck Depression Inventory, and the State-Trait Anxiety scores (Y1 and Y2); gender, race, ethnicity, and use of opiate pain medication were included as adjustment factors in the models and were not in the candidate set. Nominal, 2-sided P values were significant if P<0.05; no adjustments for multiple comparisons were made. Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) (30) and Stata (Release 13.1, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) (31).

Results

Patients

This study involves the 346 gastroparesis patients enrolled in GpR2 with either diabetic gastroparesis (DG) or idiopathic gastroparesis (IG) (Table 1). The average age of the patients was 44.3±13.1 years, 85% were female, and 90% were white. The average gastric retention of solids was 65.8±17.6% at 2 hours (normal <60%) and 31.9±21.7 at 4 hours (normal<10%). On average, the most severe gastroparesis symptoms were postprandial fullness (mean severity score of 3.5), stomach fullness (3.3), early satiety (3.2), bloating (3.0), and nausea (2.9). Of the 346 gastroparesis patients, 224 had IG, 122 had DG. Of the 122 diabetic patients, 52 had T1DM and 70 had T2DM.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients by Upper Abdominal Pain Severity in Gastroparesis

| PAGI-SYM Upper Abdominal Pain Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None, Very Mild, Mild | Moderate | Severe, Very Severe | Total | P | |

| (N=151) | (N=79) | (N=116) | (N=346) | ||

| Age at enrollment (yrs) | 45.7 (15.0) | 42.9 (11.7) | 43.4 (11.3) | 44.3 (13.1) | 0.21 |

| Gender | 0.23 | ||||

| Female | 128 (85%) | 63 (80%) | 103 (89%) | 294 (85%) | |

| Race | 0.42 | ||||

| White | 133 (88%) | 74 (94%) | 103 (89%) | 310 (90%) | |

| Gastroparesis etiology | 0.72 | ||||

| Idiopathic | 95 (62%) | 53 (67%) | 76 (66%) | 224 (65%) | |

| Diabetic | 56 (38%) | 26 (33%) | 40 (34%) | 122 (35%) | |

| Diabetes Type | 0.16 | ||||

| Type 1 | 20 (36%) | 16 (62%) | 16 (40%) | 52 (43%) | |

| Type 2 | 36 (64%) | 10 (38%) | 24 (60%) | 70 (57%) | |

| Other pain-related conditions | |||||

| IBS | 27 (18%) | 18 (23%) | 30 (26%) | 75 (22%) | 0.28 |

| Neuropathy | 15 (10%) | 8 (10%) | 20 (17%) | 43 (12%) | 0.18 |

| Migraine | 43 (28%) | 35 (44%) | 55 (47%) | 133 (38%) | 0.003 |

| Fibromyalgia | 24 (16%) | 13 (16%) | 18 (16%) | 55 (16%) | 0.98 |

| Cholecystectomy | 50 (33%) | 36 (46%) | 61 (53%) | 147 (42%) | 0.005 |

| Medication use | |||||

| Narcotic pain medications | 38 (25%) | 18 (23%) | 58 (50%) | 114 (33%) | <0.001 |

| Neuropathic pain modulators | 44 (29%) | 23 (29%) | 41 (35%) | 108 (31%) | 0.51 |

| Prokinetics | 50 (33%) | 23 (29%) | 43 (37%) | 116 (34%) | 0.52 |

| Antiemetics | 87 (58%) | 51 (65%) | 77 (66%) | 215 (62%) | 0.31 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 19 (13%) | 12 (15%) | 19 (16%) | 50 (14%) | 0.68 |

| Gastroparesis severity | <0.001 | ||||

| Grade 1 | 46 (31%) | 14 (18%) | 11 (10%) | 71 (21%) | |

| Grade 2 | 92 (61%) | 52 (66%) | 84 (73%) | 228 (66%) | |

| Grade 3 | 12 (8%) | 13 (16%) | 20 (17%) | 45 (13%) | |

| GCSI | |||||

| Overall | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.9 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | 2.7 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| PAGI-SYM Symptom Scores | |||||

| Nausea | 2.2 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Retching | 0.9 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.8) | 1.5 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.8) | 1.4 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Stomach fullness | 2.7 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Unable to finish normal meal | 2.6 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Excessively full after meals | 2.9 (1.5) | 3.8 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Loss of appetite | 2.0 (1.6) | 3.2 (1.4) | 3.3 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Bloating | 2.4 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Stomach visibly larger | 2.1 (1.8) | 3.0 (1.5) | 3.5 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 0.9 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.0) | 4.4 (0.5) | 2.6 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Upper abdominal discomfort | 1.6 (1.3) | 3.1 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.8) | 2.9 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Lower abdominal pain | 1.0 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Lower abdominal discomfort | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalized for Gp in past year | 42 (28%) | 25 (32%) | 40 (34%) | 107 (31%) | 0.51 |

| Number times vomited past day | 0.8 (2.7) | 0.7 (1.5) | 1.1 (2.3) | 0.9 (2.3) | 0.50 |

| PAGI-QOL | 3.1 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| SF-36 QOL | |||||

| Physical component | 36.8 (11.7) | 31.8 (10.8) | 29.8 (8.3) | 33.3 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Mental component | 43.3 (13.2) | 42.2 (14.2) | 39.1 (11.4) | 41.6 (13.0) | 0.03 |

| PHQ-15 | 12.6 (5.2) | 14.8 (4.8) | 16.2 (3.9) | 14.3 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| PHQ-12SS | 8.4 (4.3) | 9.8 (4.2) | 10.8 (3.6) | 9.5 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 14.9 (10.8) | 18.4 (11.2) | 20.0 (11.4) | 17.4 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| STAI | |||||

| Y1 state anxiety | 40.1 (14.2) | 42.2 (13.6) | 45.0 (12.7) | 42.2 (13.7) | 0.01 |

| Y2 trait anxiety | 40.8 (13.1) | 43.1 (13.2) | 44.4 (11.7) | 42.5 (12.8) | 0.07 |

| Gastric Emptying | |||||

| Gastric retentions of solids (%) | |||||

| 2 hour | 66.3 (17.4) | 65.6 (16.4) | 65.4 (18.8) | 65.8 (17.6) | 0.91 |

| 4 hour | 31.3 (22.0) | 31.9 (22.0) | 32.6 (21.3) | 31.9 (21.7) | 0.88 |

| Gastric retention of liquids (%) | |||||

| 1 hour | 51.1 (16.6) | 49.7 (18.4) | 48.3 (17.9) | 49.8 (17.4) | 0.68 |

| Wireless Motility Capsule Test | |||||

| Gastric Emptying Time (hours) - median (IQR) | 5.2(3.7, 15.4) | 4.8(3.5, 18.6) | 5.5(3.3, 15.2) | 5.3(3.6, 16.2) | 0.96 |

| Gastric Emptying Time>5 hrs | 62 (53%) | 29 (46%) | 55 (57%) | 146 (53%) | 0.38 |

| Water Load Satiety Test | |||||

| Volume water consumed (mL) | 375.3 (215.2) | 349.8 (218.5) | 375.5 (235.8) | 369.4 (222.5) | 0.67 |

Characteristics of Abdominal Pain

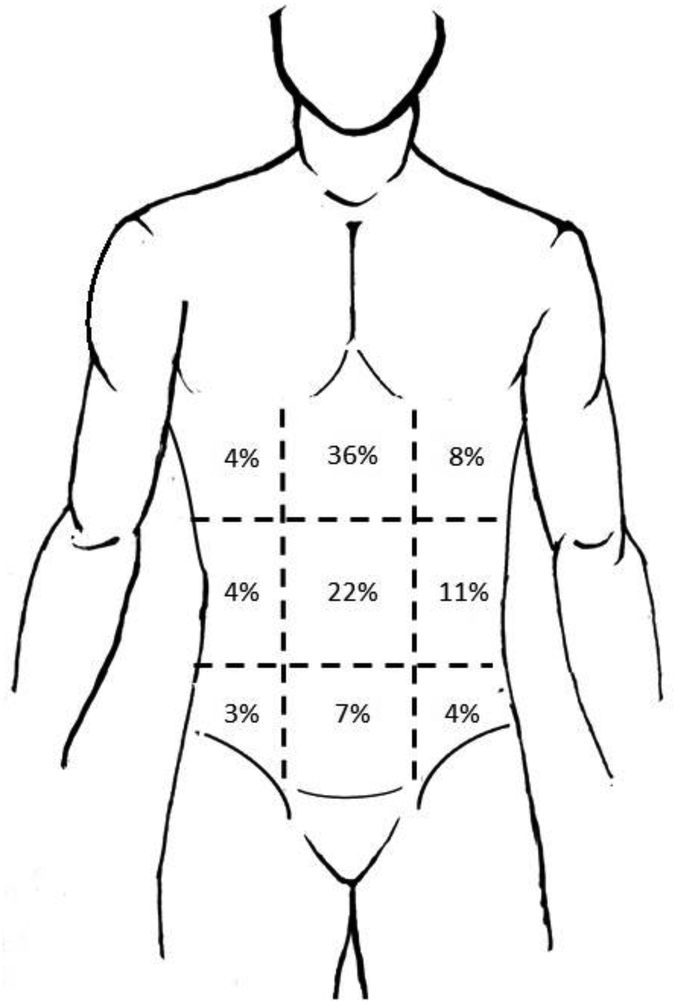

Table 2 show the characteristics of abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis: all patients (both diabetic and idiopathic), and by etiology (diabetic, idiopathic). These characteristics of abdominal pain were assessed using the McGill Pain Inventory (9) and the Spiegel Abdominal Pain Questionnaire (21). Overall, 90% of the gastroparesis patients reported abdominal pain. The abdominal pain was most commonly in upper middle (36%) or middle central (22%) abdominal locations (Figure 1). The abdominal pain was often described as cramping or sickening in character. Pain occurred every day in 52% of patients, being described as all the time and every day in 36% of patients. Abdominal pain worsened with eating in 51%, occurred at night in 51%, and interfered with sleep in 37%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Abdominal Pain in Patients with Gastroparesis by Gastroparesis Etiology

| Diabetic | Idiopathic | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ISM 22) | (N=224) | (N=346) | ||

| McGill Pain Questionnaire | ||||

| Do you experience abdominal pain | 0.46 | |||

| Yes | 108 (89%) | 203 (91%) | 311 (90%) | |

| No | 14 (11%) | 20 (9%) | 34 (10%) | |

| Location of most severe pain | 0.23 | |||

| Upper right | 5 (5%) | 8 (4%) | 13 (4%) | |

| Upper middle | 32 (30%) | 81 (40%) | 113 (36%) | |

| Upper left | 9 (8%) | 17 (8%) | 26 (8%) | |

| Middle right | 5 (5%) | 8 (4%) | 13 (4%) | |

| Middle central | 28 (26%) | 41 (20%) | 69 (22%) | |

| Middle left | 12 (11%) | 21 (10%) | 33 (11%) | |

| Lower right | 2 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 9 (3%) | |

| Lower middle | 13 (12%) | 10 (5%) | 23 (7%) | |

| Lower left | 2 (2%) | 10 (5%) | 12 (4%) | |

| Frequency of abdominal pain | 0.04 | |||

| <1 day/month | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

| 1 day/month | 2 (2%) | 6 (3%) | 8 (3%) | |

| 2–3 days/month | 7 (6%) | 8 (4%) | 15 (5%) | |

| 1 day/week | 5 (5%) | 22 (11%) | 27 (9%) | |

| >1 day/week | 44 (41%) | 53 (26%) | 97 (31%) | |

| Every day | 48 (44%) | 113 (55%) | 161 (52%) | |

| Description of abdominal pain (Scale: 0=none, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe) - Mean ± SD | ||||

| Throbbing | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.33 |

| Shooting | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.99 |

| Stabbing | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.2) | 0.36 |

| Sharp | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.1) | 0.83 |

| Cramping | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.97 |

| Gnawing | 0.9 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | 0.07 |

| Hot-burning | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.50 |

| Aching | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 0.54 |

| Heavy | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 0.04 |

| Tender | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.1) | 0.27 |

| Splitting | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.11 |

| Tiring/Exhausting | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.2) | 0.65 |

| Sickening | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.82 |

| Fearful | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.29 |

| Punishing-Cruel | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.64 |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire | ||||

| Sensory subscale | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.92 |

| Affective subscale | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.9) | 0.83 |

| Total Score | 1.2 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.88 |

| Siegel Abdominal Pain Questions | ||||

| Chronic Abdominal Pain | ||||

| Abdominal pain in the past 2 weeks. (Scale: 0- no pain to 10- worst possible) | 6.4 (2.5) | 6.0 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.3) | 0.18 |

| Number of days of abdominal pain in past 2 weeks (range: 0–14) | 9.7 (4.1) | 10.1 (4.4) | 9.9 (4.3) | 0.43 |

| Abdominal pain present all the time and every day | 0.52 | |||

| Yes | 41 (38%) | 70 (34%) | 111 (36%) | |

| No | 67 (62%) | 134 (66%) | 201 (64%) | |

| Abdominal pain worsens with eating | 0.06 | |||

| Yes | 51 (47%) | 109 (53%) | 160 (51%) | |

| No | 14 (13%) | 11 (5%) | 25 (8%) | |

| Sometimes | 43 (40%) | 84 (41%) | 127 (41%) | |

| Abdominal pain improves with eating | 0.20 | |||

| Yes | 6 (6%) | 4 (2%) | 10 (3%) | |

| No | 83 (77%) | 158 (77%) | 241 (77%) | |

| Sometimes | 19 (18%) | 42 (21%) | 61 (20%) | |

| Abdominal pain at night | 0.95 | |||

| Yes | 54 (50%) | 104 (51%) | 158 (51%) | |

| No | 9 (8%) | 15 (7%) | 24 (8%) | |

| Sometimes | 45 (42%) | 85 (42%) | 130 (42%) | |

| Abdominal pain interferes with sleep | 0.12 | |||

| Yes | 48 (44%) | 67 (33%) | 115 (37%) | |

| No | 17 (16%) | 43 (21%) | 60 (19%) | |

| Sometimes | 43 (40%) | 94 (46%) | 137 (44%) | |

| Acute abdominal pain | 0.08 | |||

| Acute episodes of abdominal pain present | 78 (72%) | 165 (81%) | 243 (78%) | |

| Severity of acute episodes (range 0–10) | 8.0 (1.9) | 8.0 (1.8) | 8.0 (1.9) | 0.87 |

| Number of days with acute episodes in 30-day period (range: 0–30) | 16.4 (9.6) | 16.0 (9.5) | 16.1 (9.5) | 0.71 |

| Number of acute episodes in one day | 4.3 (5.0) | 4.8 (11.0) | 4.6 (9.5) | 0.76 |

| Length of acute episodes | ||||

| <1 minute | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.14 |

| 1–10 minutes | 8 (10.3%) | 19 (11.5%) | 27 (11.1%) | |

| 10–30 minutes | 9 (11.5%) | 23 (13.9%) | 32 (13.2%) | |

| 30 min - 1 hour | 8 (10.3%) | 36 (21.8%) | 44 (18.1%) | |

| >1 hour - 4 hours | 24 (30.8%) | 46 (27.9%) | 70 (28.8%) | |

| All day | 17 (21.8%) | 23 (13.9%) | 40 (16.5%) | |

| 2 days | 1 (1.3%) | 6 (3.6%) | 7 (2.9%) | |

| >2 days | 11 (14.1%) | 11 (6.7%) | 22 (9.1%) | |

Figure 1.

Location of abdominal pain reported by the gastroparesis patients (combined diabetic and idiopathic etiologies). Shown are the percentages of patients reporting pain at each location. The abdominal pain was most commonly in upper middle (36%) or middle central (22%) abdominal locations.

91% of IG and 89% of DG patients reported abdominal pain. Abdominal pain occurred with eating more often in IG (53% vs 47%; p=0.06) and tended to interfere with sleep in DG than IG (44% vs 33%; p=0.12).

Acute episodes of abdominal pain were reported in 78% of patients, tending to occur more often in idiopathic than diabetic gastroparesis (81% vs 72%, p=0.08). These acute abdominal pain episodes occurred 16.1±9.5 days per month, occurring 4.6±9.5 episodes per day. The duration of the acute abdominal pain was 30 min to 4 hours in 46.9% of patients.

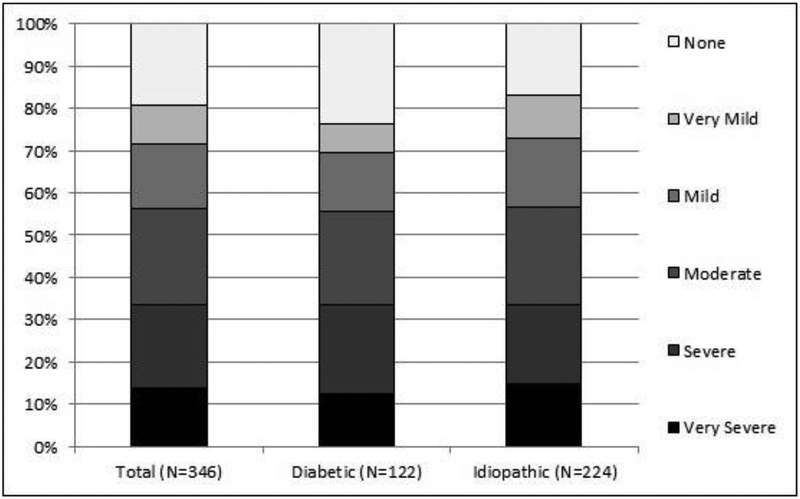

Upper Abdominal Pain Severity using PAGI-SYM

Overall, upper abdominal pain averaged 2.6±1.7 using the PAGI-SYM scoring (Table 1). This compared to 2.9±1.6 for upper abdominal discomfort, 1.8±1.6 for lower abdominal pain, and 2.0±1.5 for lower abdominal discomfort. Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1 show the severity of upper abdominal pain reported by the patients using the PAGI-SYM. Upper abdominal pain rated as severe or very severe (score of 4 or 5) on PAGI-SYM was reported by 116/346 (33.5%) patients and rated as moderate (score of 3) in another 79 patients (23%). Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was more often seen in females than males (35% vs. 25%; p=0.07), was not related to age (34% for <45 years vs 33% for ≥45 years; p=0.19), and was similar in IG and DG (34% vs. 33%; p=0.57).

Figure 2.

Severity levels of upper abdominal pain reported by the patients using the PAGISYM. Shown are the combined diabetic and idiopathic etiologies as well as the separate values for diabetic and idiopathic groups. Upper abdominal pain was rated as severe or very severe (score of 4 or 5) on PAGI-SYM by 116/346 (33.5%) patients and rated as moderate (score of 3) in another 79 patients (23%). Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was similar in IG and DG (34% vs. 33%).

Baseline characteristics of these gastroparesis patients stratified by degree of upper abdominal pain severity using PAGI-SYM is shown in Table 1. Increased upper abdominal pain severity was associated with increased severity of each of the nine GCSI symptoms (p<0.001), symptoms of GERD (p<0.001), gastroparesis severity (p<0.001), and associated with investigator assessment of symptoms of Gp (p<0.001).

Increased upper abdominal pain severity was also related to depression on BDI (p<0.001), state anxiety on STAI (p=0.01), somatization score on PHQ-15 (p<0.001) and PHQ-12 (p<0.001). Upper abdominal pain severity was associated with decreases in the SF-36 physical component (p<0.001), mental component (p=0.03), and PAGIQOL (p<0.001). The PAGI-SYM upper abdominal pain scores correlated with decreased quality of life: SF-36 physical (r=−0.31; p<0.001), SF-36 mental (r=−0.16; p=0.003), and PAGI-QOL (r=−0.36; p<0.001) scores.

Upper abdominal pain severity was associated with use of opiate medications (p<0.001), but not related to use of neuropathic pain modulators (p=0.51), tricyclic antidepressants (p=0.68), prokinetic agents (p=0.52), antiemetics (p=0.31). Upper abdominal pain severity was related to presence of migraine headaches (p=0.003), and prior cholecystectomy (p=0.005) but not to the presence of fibromyalgia (p=0.98).

Upper abdominal pain severity was not related to severity of delayed gastric emptying of solids (p=0.88 for 4 hour gastric retention) or liquid gastric emptying (p=0.68 for 1 hour gastric retention) (Table 1). Similarly, upper abdominal pain severity was also not related to gastric emptying as assessed with wireless motility capsule (p=0.96). Upper abdominal pain severity was not related to volume of water consumed during the water load test (p=0.67).

The significant relationships associated with abdominal pain were more significant in the 224 patients with idiopathic gastroparesis than in the 122 patients with diabetic gastroparesis (Supplementary Table 2). Increased upper abdominal pain was significantly associated in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis with migraine headache, prior cholecystectomy, use of narcotic pain medications, lower QOL on SF36 physical and PAGI-QOL, and somatization using either PHQ-15 or PHQ-12.

Using logistic regression analysis adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, and use of narcotic pain medications, severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was associated with increased GCSI scores (OR=2.8, 95% CI 2.0–3.8, P<0.001), use of narcotic pain medication (OR=2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.6; p=0.006), and PHQ-15 somatic symptom scores (OR=1.1, 95% CI 1.0–1.1, P=0.14) (Table 3).

Table 3.

PAGI-SYM Upper Abdominal Pain: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with severe/very severe upper abdominal pain in Gastroparesis (N=346)*

| PAGI-SYM Upper Abdominal Pain: Severe/Very Severe vs. None/Mild/Moderate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristic | Odds ratio† | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

| GCSI (per 1 unit increase in score) | 2.8 | 2.0–3.8 | <0.001 |

| Use of narcotic pain medications | 2.1 | 1.2–3.6 | 0.006 |

| PHQ-15 Somatic Symptom Score (per 1 unit increase in score) | 1.1 | 1.0–1.1 | 0.14 |

| White vs. non-white | 1.6 | 0.7–4.0 | 0.27 |

| Latino or Hispanic vs. non-Latino/Hispanic | 1.6 | 0.8–3.2 | 0.15 |

| Female vs. male | 1.5 | 0.7–3.2 | 0.30 |

Model variables selected from a candidate set of baseline variables using Akaike Information criteria (AIC) with backward selection using logistic regression. Race, ethnicity, gender, and use of narcotic pain medications were forced into the model. The candidate set of baseline variables included: age at enrollment (years), diabetes, gastroparesis etiology (diabetic vs. idiopathic), acute symptom onset vs. insidious onset, initial infectious prodrome (yes vs. no), hospitalizations in past year (yes vs. no), GCSI, PAGI-QOL, SF36 Physical and Mental components, Somatic Symptom score, Beck Depression score, State and Trait Anxiety scores, gastric retention at 2 and 4 hours.

Odds of severe abdominal pain vs. not severe abdominal pain.

Abdominal Pain Severity using The McGill Pain Questionnaire

The McGill Pain questionnaire was directed towards abdominal pain. The McGill total abdominal pain score averaged 1.2±0.6, being similar in DG and IG and with similar subscores for sensory subscale (1.2 ±0.6) and affective subscale (1.2±0.9) (Table 2). The McGill total pain scores correlated with SF-36 physical (r=−0.35; p<0.001) scores, SF-36 mental (r=−0.28; p<0.01), and PAGI-QOL (r=−0.49; p<0.01).

Using logistic regression analysis, adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, and use of opiate pain medications, factors associated with horrible or excruciating abdominal pain included female sex (3.3, 95% CI=1.0–10.5, p=0.047), increasing GCSI (OR=2.1, 95% CI=1.4–3.0, p<0.001), decreased age (OR=0.9, 95% CI=0.7–1.0, p=0.04), BDI (1.0, 95% CI 1.0–1.1, p=0.007) use of narcotic pain medication (OR=2.0; 95% CI 1.0–4.1; p=0.047), acute vs insidious onset (OR=0.6, 95% CI=0.3–1.1, p=0.12) (Table 4).

Table 4.

McGill Pain Inventory – Current Abdominal Pain: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with horrible or excruciating abdominal pain in Gastroparesis Registry 2 participants (N=344)*

| McGill Pain Inventory: Horrible/excruciating abdominal pain vs. less pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristic | Odds ratio† | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

| GCSI (per 1 unit increase in score) | 2.1 | 1.4 – 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (per 1 unit increase in score) | 1.0 | 1.0 – 1.1 | 0.007 |

| Age (per 5 year increase) | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.0 | 0.04 |

| Hospitalized in past year | 1.8 | 0.9–3.6 | 0.09 |

| Acute vs. insidious or gradual symptom onset | 0.6 | 0.3 – 1.1 | 0.12 |

| Use of narcotic pain medications | 2.0 | 1.0–4.1 | 0.047 |

| White vs. non-white | 0.4 | 0.1 −0.9 | 0.03 |

| Latino or Hispanic vs. non-Lati no/Hispanic | 1.3 | 0.5–3.0 | 0.60 |

| Female vs. male | 3.3 | 1.0–10.5 | 0.047 |

Model variables selected from a candidate set of baseline variables using Akaike Information criteria (AIC) with backward selection using logistic regression. Race, ethnicity, gender, and use of narcotic pain medications were forced into the model. The candidate set of baseline variables included: age at enrollment (years), diabetes, gastroparesis etiology (diabetic vs. idiopathic), acute symptom onset vs. insidious onset, initial infectious prodrome (yes vs. no), hospitalizations in past year (yes vs. no), GCSI, PAGI-QOL, SF36 Physical and Mental components, Somatic Symptom score, Beck Depression score, State and Trait Anxiety scores, gastric retention at 2 and 4 hours.

Odds of horrible or excruciating abdominal pain vs. less.

The McGill total pain score was correlated with the PAGI-SYM upper abdominal pain severity score (r=0.54; p<0.001).

Pain Severity using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) asked about pain in general. The BPI severity score assessing the severity of pain at worst, pain at its least, and average on a 10 point scale) was 4.9±2.2 (Table 5). The BPI interference score (average of the interference of pain with general activity, mood, walking, normal work, relations, sleep, enjoyment of life on a 10 point scale) was 5.2±2.7. The BPI severity scores were correlated with SF-36 physical (r=−0.57; p<0.001), SF-36 mental (r=−0.32; p<0.01), and PAGI-QOL (r=−0.56; p<0.01) scores.

Table 5.

Brief Pain Inventory

| Brief Pain Inventory | Diabetic (N=122) | Idiopathic (N=224) | Total (N=346) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you had pain today (other than everyday kinds of pain) | 0.67 | |||

| Yes | 97 (80%) | 183 (82%) | 280 (81%) | |

| No | 25 (20%) | 41 (18%) | 66 (19%) | |

| Pain over last 24 hours (range 0–10, where 0=no pain, 10=worst pain you can imagine) | ||||

| Worst pain in past 24 hrs | 6.6 (2.8) | 6.3 (2.3) | 6.4 (2.5) | 0.32 |

| Pain at its least in past 24 hrs | 3.6 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.4) | 0.005 |

| Pain on average over past 24 hrs | 5.7 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.0) | 5.4 (2.1) | 0.04 |

| Pain right now | 5.4 (2.9) | 4.5 (2.8) | 4.8 (2.9) | 0.01 |

| How much relief have pain treatments/medications provided | 49.3 (30.8) | 44.6 (30.4) | 46.1 (30.6) | 0.30 |

| Pain Severity Score* | 5.3 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.0) | 4.9 (2.2) | 0.02 |

| Pain Interference Score† | 5.7 (2.8) | 4.9 (2.6) | 5.2 (2.7) | 0.02 |

| How pain has interfered with the following over the past 24 hours (range 0–10, where 0=does not interfere, 10=interferes completely): | ||||

| General activity | 6.0 (3.2) | 5.1 (3.1) | 5.4 (3.1) | 0.03 |

| Mood | 5.5 (3.3) | 5.2 (3.1) | 5.3 (3.2) | 0.51 |

| Walking ability | 5.4 (3.4) | 4.0 (3.2) | 4.5 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Normal work | 6.2 (3.3) | 5.4 (3.1) | 5.7 (3.2) | 0.03 |

| Relations with other people | 4.6 (3.5) | 3.9 (3.3) | 4.2 (3.4) | 0.14 |

| Sleep | 6.4 (3.1) | 5.3 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.3) | 0.006 |

| Enjoyment of life | 5.8 (3.4) | 5.4 (3.3) | 5.5 (3.3) | 0.33 |

Values are N (%) or Mean (SD). P-values derived from Fisher’s exact test for categorical measures and ANOVA for continuous measures.

Pain Severity Score=Average of the four pain severity scores over past 24 hours (worst pain, pain at its least, pain on average, and pain right now), with higher values indicating more severe pain.

Pain Interference Score=Average of the seven interference scores (general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, and enjoyment of life), with higher values indicating more interference from pain.

The BPI captured increased pain severity in DG compared to IG (5.3±2.4 vs 4.7±2.0; p=0.02) as well as increased pain interference score in DG compared to IG (5.7±2.8 vs 4.9±2.6; p=0.02) (Table 5).

Using logistic regression analysis, adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, and use of opiate pain medications, factors associated with BPI scores ≥8 included diabetic (vs. idiopathic) etiology (OR=3.0, 95% CI=1.2–7.2, P=0.02), decreased PAGI-QOL (OR=0.4, 95% CI=0.2–0.7, p=0.002), decreased SF-36 physical score (OR=0.7, 95% CI=0.5–0.9, p=0.006), increased depression on BDI (OR=1.1, 95% CI=1.0–1.2, p<0.001), increased State Anxiety (OR=1.5, 95% CI=1.1–2.0, P=0.01), but decreased Trait Anxiety (OR=0.6, 95% CI=0.4–0.9, P=0.02), (Table 6).

Table 6.

Brief Pain Inventory: Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with Brief Pain Inventory scores ≥8 in Gastroparesis Registry 2 participants (N=344)*

| Brief Pain Inventory Score ≥8 vs. <8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristic | Odds ratio† | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

| PAGI-QOL (per 1 unit increase in score) | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 | 0.002 |

| SF-36 Physical Score (per 5 unit increase in score) | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.006 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (per 1 unit increase in score) | 1.1 | 1.0–1.2 | <0.001 |

| STAI - State Anxiety (per 5 unit increase in score) | 1.5 | 1.1 −2.0 | 0.01 |

| STAI - Trait Anxiety (per 5 unit increase in score) | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 | 0.02 |

| PHQ-15 (per 1 unit increase in score) | 1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | 0.04 |

| Diabetic vs. idiopathic Gp | 3.0 | 1.2–7.2 | 0.02 |

| Hospitalized in past year | 2.0 | 0.8–4.9 | 0.12 |

| Use of narcotic pain medications | 1.5 | 0.7–3.6 | 0.31 |

| White vs. non-white | 0.6 | 0.2–1.9 | 0.40 |

| Latino or Hispanic vs. non-Latino/Hispanic | 0.8 | 0.3–2.3 | 0.67 |

| Female vs. male | 1.4 | 0.4–4.9 | 0.58 |

Model variables selected from a candidate set of baseline variables using Akaike Information criteria (AIC) with backward selection using logistic regression. Race, ethnicity, gender, and use of narcotic pain medications were forced into the model. The candidate set of baseline variables included: age at enrollment (years), diabetes, gastroparesis etiology (diabetic vs. idiopathic), acute symptom onset vs. insidious onset, initial infectious prodrome (yes vs. no), hospitalizations in past year (yes vs. no), GCSI, PAGI-QOL, SF-36 Physical and Mental components, Somatic Symptom score, Beck Depression score, State and Trait Anxiety scores, gastric retention at 2 and 4 hours.

Odds of Brief Pain Inventory score ≥ 8 vs. <8, on a scale of 0–10, with higher score indicating worse pain (0=no pain, 10=pain as bad as you can imagine).

The BPI Severity Score correlated with the PAGI-SYM upper abdominal severity score (r=0.39; p<0.001) and with McGill Total Pain Score (r=0.49; p<0.001).

Discussion

This study characterizes the abdominal pain that occurs in patients with gastroparesis and the types of gastroparesis patients reporting abdominal pain. The study shows that abdominal pain is common in patients with gastroparesis, being present in 90% of patients with either idiopathic or diabetic gastroparesis. Abdominal pain occurred at severe/very severe levels in 34% of gastroparesis patients. Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was associated with increased GCSI scores, PHQ-15 somatic symptom scores, and use of opiate medications.

This study shows that abdominal pain represents a significant symptom in some patients with gastroparesis as it is associated with impaired quality of life as evidenced using PAGI-QOL and SF36 QOL instruments. In one of the first studies focusing on pain in gastroparesis, Hoogerwerf et al reported the prevalence of abdominal pain in gastroparesis to be 89% (5), being similar to that of nausea and early satiety. Cherian et al described abdominal pain present in 90% of patients with gastroparesis, a prevalence rate compared to nausea (6). Our NIH Gastroparesis Consortium has previously described abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis using data from our first gastroparesis registry (4). Of patients with gastroparesis, 72% noted abdominal pain with abdominal pain the predominant symptom in 19% compared to nausea or vomiting in 57%. These three studies suggest that abdominal pain is present in many patients with gastroparesis with comparable prevalence to nausea and vomiting. This present study adds to this information of abdominal pain in gastroparesis by careful description of the abdominal pain, performing additional physiologic testing in the patients, and describing the patients that report abdominal pain.

The abdominal pain was most commonly located in upper or central midline abdomen, often described as cramping or sickening in character. Pain occurred every day in 52% of patients, being described as all the time and every day in 36% of patients. Abdominal pain worsened with eating in 51%, occurred at night in 51%, and interfered with sleep in 37%. Using the PAGI-SYM questionnaire, upper abdominal pain occurred at severe/very severe levels in 34% of gastroparesis patients. Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was associated with increased GCSI scores, PHQ-15 somatic symptom scores, and use of opiate medications.

Recent consensus among pain specialists suggests pain should be captured using several different instruments (32). In addition to using PAGI-SYM, our study used several other validated questionnaires to assess the patient’s pain: Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and McGill Pain Questionnaires. The BPI is one of the most widely used measurement tools for assessing clinical pain (10) and used to evaluate the severity of pain and the impact of pain on the patient’s daily functioning. Overall, the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) severity score was 4.9±2.2 in our patients with gastroparesis. The BPI scores were associated with lower SF-36 QOL and PAGI-QOL scores. The BPI captured increased pain severity in DG compared to IG as well as increased pain interference score in DG compared to IG; this may be related in part to other pain syndromes in diabetics, such as neuropathy. We also used the McGill Pain Questionnaire allowing individuals to provide a good description of the quality and intensity of their pain (11). In our gastroparesis patients, the McGill total pain score averaged 1.2±0.6; similar in DG and IG. The McGill total pain scores correlated with SF-36 physical QOL scores. There was modest correlation of McGill total pain score and Brief Pain Inventory with PAGI-SYM upper abdominal pain severity scores.

Is abdominal pain part of gastroparesis? In the initial drafts of the GCSI, abdominal pain was not included (3). This study shows that increasing abdominal pain was associated with increasing severity of each of the GCSI gastroparesis symptoms suggesting that abdominal pain is part of the gastroparesis experience. However, abdominal pain was not associated with gastric emptying using either the 2 or 4 hour gastric retention of solids, using gastric emptying of liquids in the presence of solids, or gastric emptying of the wireless motility capsule.

The lack of correlation between abdominal pain and gastric emptying suggests other mechanisms may be responsible for the abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis, such as changes in gastric accommodation or gastric distension (33). Our studies with water load testing in this study and intragastric meal distribution in a prior study suggest that impaired accommodation does not explain the occurrence of abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis. Abdominal pain could be from visceral hypersensitivity that has been suggested to occur in diabetic gastroparesis (34,35). Hypersensitivity to gastric distension has been associated with higher prevalence of epigastric pain, early satiety and weight loss (33). Abdominal pain can be a manifestation of autonomic neuropathy. However, one small study found that more severe forms of visceral afferent neuropathy were associated with fewer rather than more severe symptoms in diabetic gastroparesis (36). Patients with more severe pain have been reported to have histologic evidence of anatomic abnormalities in the enteric nervous system – fewer S100 neural fibers (37). Unexplored as a factor in abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis are central mechanisms. Altered central nervous system processing to gastric distension has been found in patients with functional dyspepsia (38). Abdominal pain was associated with vomiting severity: severe vomiting or more frequent vomiting involves abdominal rectus muscle; abdominal wall pain be occurring in some of these patients.

The gastroparesis patients were assessed for somatization using PHQ-15, a brief, self-administered questionnaire that is useful in screening for somatization (17). Overall, PHQ-15 somatic symptoms score averaged 14.3±5.0; normal values are generally less than 10 (18). Increasing somatic symptoms scores using PHQ-15 were seen with increasing PAGI-SYM upper abdominal pain scores. This was also seen with the PHQ-12 often used in GI studies which removes the three GI symptoms in PHQ-15 (19). Using logistic regression analysis adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, and use of narcotic pain medications, severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was associated with increased GCSI scores, and PHQ-15 somatization scores. The association with somatization gives the sense that abdominal pain seen in gastroparesis patients may be related to a chronic pain syndrome independent of gastroparesis. Of note, the abdominal pain was associated with other pain disorders, being associated with migraine headaches as well as with prior cholecystectomy.

Increasing abdominal pain was associated with increasing use of narcotic pain medication, but not other neuropathic pain medications that are now being used more frequently for pain syndromes. The use of narcotics adds several caveats to this study. Narcotics can delay gastric emptying. If patients do not stop these for assessment of gastric emptying (as they are instructed), one could get the false impression that they have gastroparesis when in fact, the narcotics are delaying gastric emptying. Narcotics can also cause symptoms of nausea and vomiting themselves. Chronic use of narcotics can also upregulate pain, which is described in the narcotic bowel syndrome (39). Opiates although used for treatment of pain, may be in part, a reason for the pain.

This study uses the large, prospectively collected data from carefully assessed patients enrolled at the centers of the NIH Gastroparesis Consortium. The high degree of abdominal pain might represent a referral bias, since more severe patients are referred to these academic tertiary centers if they have refractory symptoms. Importantly, most clinicians see patients with gastroparesis having abdominal pain; our study allows characterization of these types of patients and define clinical features helping to form a foundation for future natural history and treatment studies of pain in gastroparesis. Other comorbidities may coexist with gastroparesis. Some of the patients may have conditioned vomiting superimposed on their gastroparesis. A number may have concomitant irritable bowel syndrome with their gastroparesis.

In summary, this study demonstrates that abdominal pain is common in patients with gastroparesis, both idiopathic and diabetic. Abdominal pain occurred at severe/very severe levels in 34% of gastroparesis patients. Severe/very severe upper abdominal pain was associated with increased GCSI scores, PHQ-15 somatization scores, and use of opiate medications. Better understanding of the pathophysiology and treatment of abdominal pain in gastroparesis is needed to reduce morbidity from this under-recognized but important symptom. Abdominal pain in patients with gastroparesis has been underappreciated. There is need to study this abdominal pain and the effects of treatments on pain. Delayed gastric emptying does associate with the severity of abdominal pain; accelerating (or even normalizing) gastric emptying will likely not help abdominal pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants U01DK073983 (Pasricha), U01DK073975 (Parkman), U01DK073985 (Hasler), U01DK074007, U01DK073974, U01DK074008 (Tonascia), U01DK112193 (Kuo).

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01696747

No conflicts of interest exist.

Contributor Information

Henry P. Parkman, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA

Laura A. Wilson, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD

William L. Hasler, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

Kenneth L. Koch, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC

Thomas L. Abell, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY

Ron Schey, Temple University.

Braden Kuo, Harvard Medical School.

William J. Snape, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, CA

Linda Nguyen, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Frank Hamilton, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

Pankaj J. Pasricha, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD

References

- 1.Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1592–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L, American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:18–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of a patient-assessed gastroparesis symptom severity measure: the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18:141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasler WL, Wilson LA, Parkman HP, Koch KL, Abell TL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, McCallum RW, Sarosiek I, Farrugia G, Calles J, Lee L, Tonascia J, Unalp-Arida A, Hamilton F. Factors related to abdominal pain in gastroparesis: contrast to patients with predominant nausea and vomiting. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013;25:427–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoogerwerf WA, Pasricha PJ, Kalloo AN, Schuster MM. Pain: the overlooked symptom in gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94:1029–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherian D, Sachdeva P, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Abdominal pain is a frequent symptom of gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:676–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkman HP, Hallinan EK, Hasler WL, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Calles J, Snape WJ, Abell TL, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Clarke J, Miriel L, Lee L, Tonascia J, Hamilton F; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC). Nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis: similarities and differences in idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;28:1902–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkman HP, Hallinan EK, Hasler WL, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Nguyen L, Snape WJ, Abell TL, McCallum RW, Sarosiek I, Pasricha PJ, Clarke J, Miriel L, Tonascia J, Hamilton F; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC). Early satiety and postprandial fullness in gastroparesis correlate with gastroparesis severity, gastric emptying, and water load testing. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29(4). doi: 10.1111/nmo.12981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rentz AM, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res 2004;13:1737–49.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, Harding G, Coyne KS, Peirce-Sandner S, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain 2009;144:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abell TL, Bernstein VK, Cutts T, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2006;18:263–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De la Loge C, Trudeau E, Marquis P, et al. Cross-cultural development and validation of a patient self-administered questionnaire to assess quality of life in upper gastrointestinal disorders: the PAGI-QOL. Qual Life Res 2004;13:1751–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36® Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, et al. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology 1998;31:160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002;64:258–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of a screening instrument (PHQ-15) for somatization syndromes in the general population. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiller RC, Humes DJ, Campbell E, Hastings M, Neal KR, Dukes GE, Whorwell PJ. The Patient Health Questionnaire 12 Somatic Symptom scale as a predictor of symptom severity and consulting behaviour in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and symptomatic diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010. September;32:811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004;5:133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spiegel BM, Bolus R, Harris LA, Lucak S, Chey WD, Sayuk G, Esrailian E, Lembo A, Karsan H, Tillisch K, Talley J, Chang L. Characterizing abdominal pain in IBS: guidance for study inclusion criteria, outcome measurement and clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:1192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tougas G, Eaker EY, Abell TL, et al. Assessment of gastric emptying using a low fat meal: establishment of international control values. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, et al. Consensus Recommendations for Gastric Emptying Scintigraphy. Am J Gastro 2008;103:753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sachdeva P, Malhotra N, Pathikonda M, Khayyam U, Fisher RS, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Gastric emptying of solids and liquids for evaluation for gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:1138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch KL, Hong SP, Xu L. Reproducibility of gastric myoelectrical activity and the water load test in patients with dysmotility-like dyspepsia symptoms and in control subjects. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;31:125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasler WL, May KP, Wilson LA, Van Natta M, Parkman HP, Pasricha PJ, Koch KL, Abell TL, McCallum RW, Nguyen LA, Snape WJ, Sarosiek I, Clarke JO, Farrugia G, Calles-Escandon J, Grover M, Tonascia J, Lee LA, Miriel L, Hamilton FA; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC). Relating gastric scintigraphy and symptoms to motility capsule transit and pressure findings in suspected gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30(2). doi: 10.1111/nmo.13196. Epub 2017 Sep 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agresti A Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Second ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akaike H A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS software, version 9.3 of the SAS system for Windows. Cary, NC, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.StataCorp. 2011. Stata statistical software: release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Kerns RD, Ader DN, Brandenburg N, Burke LB, Cella D, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Dionne R, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Katz NP, Kehlet H, Kramer LD, Manning DC, McCormick C, McDermott MP, McQuay HJ, Patel S, Porter L, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Revicki DA, Rothman M, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Stauffer JW, von Stein T, White RE, Witter J, Zavisic S. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Piessevaux H, Janssens J. Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2001;121:526–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samsom M, Salet GA, Roelofs JM, Akkermans LM, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Compliance of the proximal stomach and dyspeptic symptoms in patients with type I diabetes mellitus. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:2037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar A, Attaluri A, Hashmi S, Schulze KS, Rao SS. Visceral hypersensitivity and impaired accommodation in refractory diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathmann W, Enck P, Frieling T, Gries FA. Visceral afferent neuropathy in diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care 1991;14:1086–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lahr CJ, Friffith J, Subramony C, Hallby L, Adams K, Panne EE, Schmiec R, Islam S, Salamer J, Spree D, Kothari T, Kedar A, Nhkeffn Y, Abell T. Gastric electric stimulation for abdominal pain in patients with symptoms of gastroparesis. American Surgeon 2013;79:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Dupont P, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Dirix S, van Laere K, Bormans G, Vanderghinste D, Demyttenaere K, Fishler B, Tack J. Regional brain activity in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2010;139:36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drossman D, Szigethy E. The narcotic bowel syndrome: a recent update. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl 2014;2:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.