Abstract

A congeneric series of 1,2-azaborine ligands was used to study the relationship between the steric demand of the ligand and hydrogen bonding strength in the context of ligand-protein binding using engineered T4 lysozymes as the model biomacromolecule. The hydrogen bond strength values were extracted from experimentally accessible binding free energies using the Double Mutant Cycle analysis. With increasing steric demand, the NH…102Q hydrogen bonding interaction is weakened, however, this weakening of the hydrogen bonding interaction occurs in discreet steps rather than in incremental fashion.

Introduction

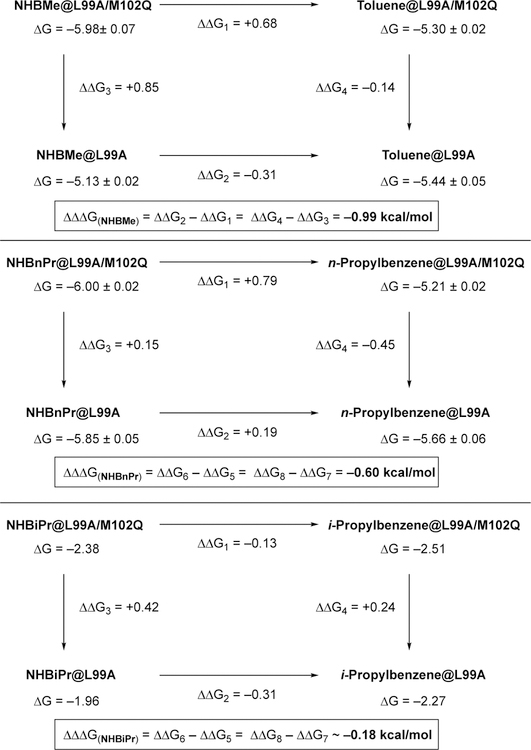

1,2-Dihydro-1,2-azaborine (abbreviated as 1,2-azaborine) is a boron-nitrogen-containing aromatic species that is isosteric with the ubiquitous benzene motif.1 Our lab is interested in exploring the 1,2-azaborine motif as a potential new pharmacophore in medicinal chemistry applications.2 There are two features that distinguish an 1,2-azaborine3 from benzene that can be exploited to translate the expanded the chemical space into new functions: 1) the relatively strong dipole of 2.1D in 1,2-azaborine,4 and 2) the N-H group in the 1,2-azaborine as H-bond donor (Scheme 1, top).5 Indeed, we determined that BN isosteres of biologically active biaryl carboxamides are more aqueous soluble and also more bioavailable than their carbonaceous counterparts due to the presence of the more polar 1,2-azaborine (Scheme 1, middle).6 Furthermore, we provided structural evidence of hydrogen bonding between the NH group of 1,2-azaborine and the C=O group of the glutamine (Q) side chain of the L99A/M102Q T4 lysozyme cavity (Scheme 1, bottom).5

Scheme 1.

Distinguishing features of the 1,2-azaborine motif.

Hydrogen bonding is a fundamentally important structural organizing interaction in biomacromolecules and in biologically relevant processes. It contributes to directionality and specificity in ligand-protein binding interactions,7 and as a consequence, hydrogen bonding plays an important role in the optimization of lead targets in drug design and development.8 We anticipate that in most biologically active 1,2-azaborines the NH group will be flanked by a boron atom that is substituted. How the size of the boron substituent influences the capability of the NH group of the 1,2-azaborine to serve as a hydrogen bond donor is of fundamental interest for the development of the 1,2-azaborine motif as a pharmacophore. More generally, to the best of our knowledge, a systematic experimental and quantitative thermodynamic investigation of the strength of a hydrogen bond as a function increasing steric environment in protein-ligand binding has not been explored.9 The scarcity of precedent is arguably due to the fact that the strength of the hydrogen bonding interaction is experimentally difficult to deconvolute from other factors (e.g., desolvation, hydrophobic interaction, entropy) that contribute to the experimentally accessible overall binding free energy of the ligand to its protein target, particularly under biologically relevant aqueous conditions.10

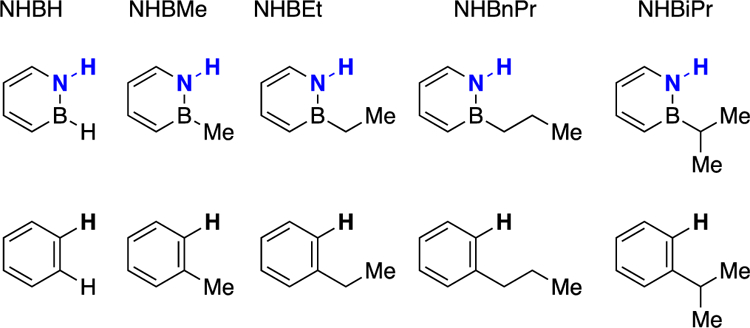

The isosteric relationship between 1,2-azaborines and arenes combined with the modularity of the arene recognition pocket of engineered T4 lysozymes provides a unique platform to “extract” the hydrogen bonding “enthalpy” from experimentally accessible binding free energies via the Double Mutant Cycle analysis11 (Scheme 2). In this communication, we investigate the binding of a congeneric series of B-substituted 1,2-azaborines to L99A and L99A/M102Q mutant forms of T4 lysozymes and evaluate the strength of the NH…102Q hydrogen bond interaction as a function of increasing steric environment at boron (H, Me, Et, n-Pr, i-Pr). We find that the NH…102Q hydrogen bond interaction decreases in strength with increasing steric demand of the boron substituents. However, the observed decrease in hydrogen bond strength is not incremental or “continuous” but rather appears to take place in discreet steps.

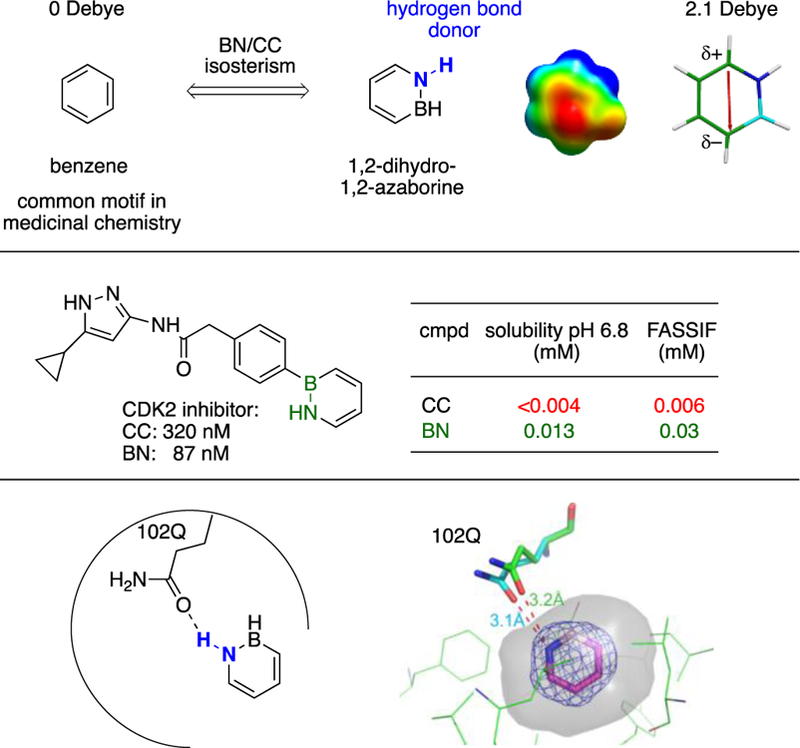

Scheme 2.

This work: Evaluation of hydrogen bond strength as a function of steric environment via Double Mutant Cycle analysis.

Since its introduction by Fersht in 1984,12 the thermodynamic cycle or Double Mutant Cycle analysis has established itself as standard practice for the quantification/estimation of a specific non-covalent interaction from measurable binding free energies in proteins13 as well as in synthetic chemical systems.11,14 The specific non-covalent interaction in question for us is the hydrogen bonding interaction (Scheme 2). The binding free energy ΔGw of a “wild type” 1,2-azaborine to the “wild type” protein will encompass in addition to 1) the NH…102Q hydrogen bonding also contributions from 2) desolvation of the 1,2-azaborine molecule from water, 3) the hydrophobic effect of binding of the aromatic species to the arene recognition cavity, and 4) entropy effect of displacement of H2O molecules from the cavity. By measuring additional binding free energies of “mutant” species where the hydrogen bonding interaction is absent (i.e., ΔGx, ΔGy, ΔGz), the energetic contribution from hydrogen bonding (ΔΔΔG = ΔΔG2 – ΔΔG1 or ΔΔG4 – ΔΔG3) can be extracted. It is worth noting that a double mutation, one on the receptor and one on the ligand, each mutant lacking the interacting groups of interest, is essential for the isolation of the hydrogen bonding contribution. For example, if we were just to measure the binding difference ΔΔG1 based on ligand mutation, i.e., 1,2-azaborine vs. benzene, we would miss the difference in energy from desolvation from water between 1,2-azaborine and benzene (ΔΔG2) that also needs to be accounted for. Similarly, if we were to just consider the binding difference ΔΔG3 based on receptor mutation, we would not account for the energetic change associated with ligand-receptor fit (ΔΔG4) as a result of the change of the side chain residue.

Results and discussion

The Double Mutant Cycle analysis was employed here to evaluate the hydrogen bonding strength as a function of steric environment of the 1,2-azaborine ligand. Our experiments use L99A/M102Q15 as the wild type protein and L99A16 as the “mutant” version of the enzyme. The wild type ligand is the 1,2-azaborine ligand, and its carbonaceous counterpart (Scheme 3) is the “mutant” version. The binding free energies (ΔGw, ΔGx, ΔGy, ΔGz) were determined by isothermal titration calorimetry experiments (ITC).10,17

Scheme 3.

A congeneric series of 1,2-azaborine ligands and its carbonaceous analogues.

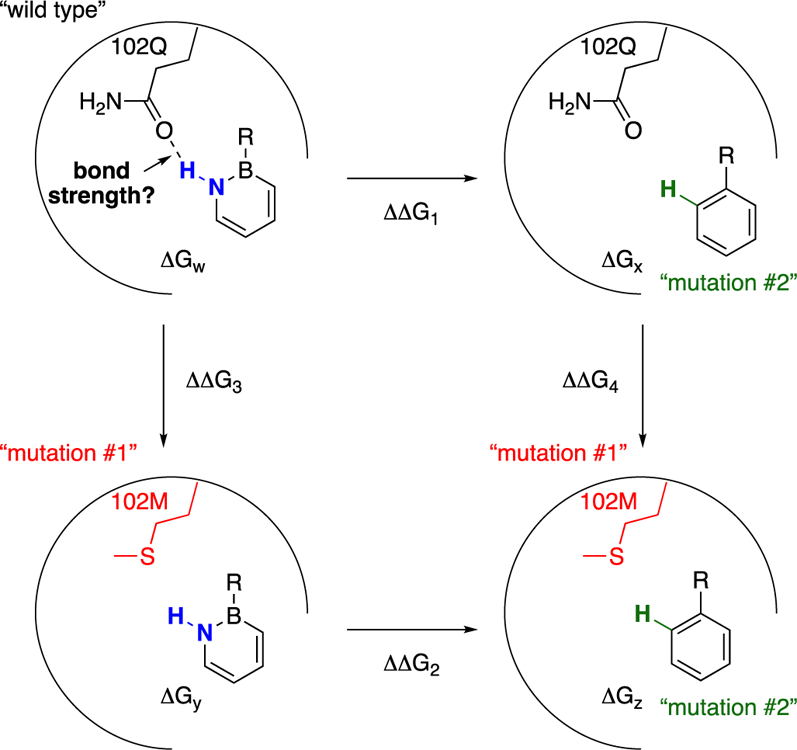

We have previously reported the Double Mutant Cycle for NHBH and NHBEt.5 To complete the congeneric series, we report here the Double Mutant Cycle for NHBMe, NHBnPr, and NHBiPr (Scheme 4). We note that with increasing size of the boron substituent, the solubility of the ligand decreases so that ITC conditions that differ slightly from the originally reported protocol needed to be employed (see Supporting Information for experimental details). However, experimental conditions were kept consistent within a thermodynamic cycle. Although ITC measurements can produce numerical values for ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS, we focus in our analysis only on the Gibbs free energy of binding. ITC experiments do not independently produce ΔH and ΔS values (ΔS is rather calculated from ΔG and ΔH via ΔG = ΔH –TΔS), thus ΔH and ΔS values from ITC experiments are perhaps more prone to misinterpretation due the fact that they are correlated and compensate to match the measured value of ΔG.18 For NHBiPr and i-Propylbenzene ligands, we used the ligand displacement method19 to account for their low binding affinity.

Scheme 4.

The Double Mutant Cycle analysis for a congeneric ligand series.

Table 1 summarizes the results of the hydrogen bonding strength (ΔΔΔG from Scheme 4) between five congeneric 1,2-azaborine ligands and the glutamine residue of the L99A/M102Q.20 Each binding free energy data point (reported as the average value and standard deviation of ΔG) in Scheme 4 was obtained from a set of five titration experiments, and the standard deviation of the mean for binding affinity Ka was calculated as the error bar shown in Table S1, and the error range of the hydrogen bonding strength ΔΔΔG in Table 1 was calculated by the propagation of error. The data for the low-binding affinity ligands NHBiPr and i-propylbenzene was averaged from two data points.

Table 1.

The hydrogen bonding strength.

| Ligand | Hydrogen bonding energy ΔΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| NHBHa | −0.94±0.08 |

| NHBMe | −0.99±0.09 |

| NHBEta | −0.64±0.07 |

| NHBnPr | −0.60±0.08 |

| NHBiPr | −0.18 |

From reference 5.

As can be seen from Table 1, the evaluated NH…102Q hydrogen bond strength for NHBH and NHBMe are about the same within the experimental error range. The hydrogen bonding interaction is weakened when the size of the boron substituent is increased from methyl to ethyl by about 0.3 kcal/mol. However, no further decrease in hydrogen bonding strength is observed when the B-ethyl substituent is replaced with a B-nPr substituent. A significant decrease of hydrogen bonding interaction is observed going from a primary B-nPr substituent to the more sterically encumbered secondary B-iPr substituent. The lower energetic limit for a hydrogen bond strength is considered to be 0.2 kcal/mol (e.g., for the interaction between CH4 and FCH3).21 Thus, the observed hydrogen bonding strength for the NHBiPr ligand (0.18 kcal/mol) can be considered negligible. In other words, the observed weak binding of NHBiPr and i-propylbenzene to T4 lysozyme mutants (Scheme 4) has likely no contribution from hydrogen bonding effects. In an IR study probing the binding interaction between ethers (serving has hydrogen bond acceptors) and phenol (hydrogen bond donor) in CCl4 solvent, the difference in phenol binding free energy between Et2O and n-Bu2O is 0.2 kcal/mol.9b The relatively small free energy penalty as a consequence of the increased steric demand is comparable with our observed values.

It has been reported that L99A T4 lysozyme mutants accommodate a congeneric series of substituted benzenes in three discreet conformations rather than through incremental conformational changes.22 Specifically, protein X-ray crystallographic studies reveal that a “closed” conformation of the arene-recognition cavity is dominant for the benzene- and toluene-bound proteins. An “intermediate” conformation that partially opens the cavity to bulk solvent is observed as a significant contributor for ethyl-, n-propyl-, n-butyl-, and s-butylbenzene-bound proteins, while for n-pentyl- and n-hexylbenzene bound proteins an “open” conformation with a solvent-exposed cavity is observed as a major contributor. Our data in Table 1 indicate that changes in the strength of hydrogen bonding as a function of steric environment can also occur in discreet steps. We have previously shown that the hydrogen bonding distance between the Q102 carbonyl and NH group of the bound parent 1,2-azaborine is 3.1 Å and 3.2 Å (there are two Q102 sidechain conformations), whereas the hydrogen bonding distance for NHBEt is 3.2 Å and 3.6 Å.5 Thus, as expected, the strength of the determined hydrogen bond interaction correlates inversely with the observed hydrogen bond distances. Overall, we believe the observed trend shown in Table 1 is consistent with both the discreet protein conformation as well as the immediate local steric influence exerted by the boron substituent playing a role. In other words, the positioning of the Q102 residue (and as a consequence its proximity to the hydrogen-bond donor on the ligand) can possibly be influenced by the protein conformation (closed, intermediate, open; that is guided by the ligand size) and/or directly by the size of the proximal boron substituent. For NHBH and NHBMe- bound proteins, the “closed” protein conformation is likely dominant, and the local steric effect exerted by the boron substituent (H vs. Me) may be negligible, resulting in similar observed hydrogen bond strength. The transition from NHBMe to NHBEt/NHBnPr may involve a protein conformational change from “closed” to “intermediate” state, possibly influencing the positioning of the Q102 residue that results in a weaker hydrogen bond. Finally, the local steric demand exerted by the B-iPr group in the NHBiPr- bound proteins may prove to be too prohibitive for hydrogen bonding to occur, irrespective of the protein conformation.

Conclusions

In summary, we evaluated the hydrogen bonding strength between a small-molecule ligand and a protein as a function of ligand sterics using a congeneric series of 1,2-azaborine ligands and L99A/M102Q T4 lysozyme. We extracted the hydrogen bond strength values from experimentally accessible binding free energies using the Double Mutant Cycle analysis, and we conclude that, as expected, with increasing steric demand, the hydrogen bonding interaction is weakened. However, we find that this weakening of the hydrogen bonding interaction can occur in discreet steps rather than in incremental fashion. In view of the importance of hydrogen bonding in drug design campaign, this work provides additional fundamental reference data to help establish 1,2-azborines as a potential pharmacophore in medicinal chemistry applications.

Experimental

Synthetic procedures

General methods

All oxygen- and moisture-sensitive manipulations were carried out under an inert atmosphere (N2) using either standard Schlenk techniques or a glove box. THF, Et2O, CH2Cl2, toluene and pentane were purified by passing through a neutral alumina column under argon. Pd/C was purchased from Strem and heated under high vacuum at 100 °C for 12 hours prior to use. Silica gel (230–400 mesh) was dried for 12 hours at 180 °C under high vacuum. Flash chromatography was performed with this silica gel under an inert atmosphere. All other chemicals and solvents were purchased and used as received. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian VNMRS 600 MHz, VNMRS 500 MHz, INOVA 500 MHz, or VNMRS 400 MHz spectrometer. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Labs. 11B NMR spectra were externally referenced to BF3•Et2O (δ 0). All NMR chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to residual solvent for 1H and 13C NMR. Infrared spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker ALPHA-Platinum FT-IR Spectrometer with ATR-sampling module. High-resolution mass spectrometry analyses were performed by direct analysis in real time (DART) on a JEOL AccuTOF DART instrument.

Synthesis of 1,2-Azaborines

2-methyl-1,2-dihydro-1,2-azaborinine (NHBMe)23 was prepared according to literature methods. 2-propyl-1,2-dihydro-1,2-azaborinine (NHBnPr), 2-isopropyl-1,2-dihydro-1,2-azaborinine (NHBiPr) was synthesized from compound S1 as follows:

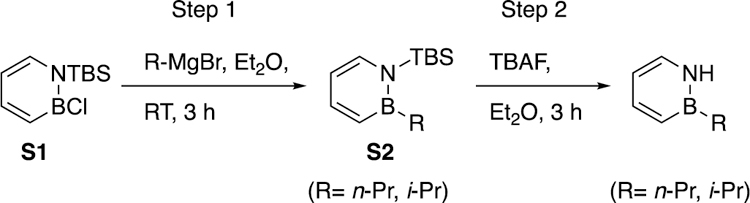

Step 1. Boron substitution by Grignard reagent.

In a glove box, a 50 mL flask was charged with compound S1 (1.00 g, 4.39 mmol), a magnetic stir bar and 7.0 mL diethyl ether. The reaction mixture was transferred to N2 line and cooled to –40°C. n-Propyl or methyl magnesium chloride (2.0 M, 2.39 mL, 4.79 mmol) was added dropwise to the stirred cold reaction mixture. The reaction was allowed to warm up to room temperature and allowed to stir at room temperature in the glove box. The reaction progress was monitored by 11B NMR. 11B NMR indicated that the reaction was complete after 3 hours. Volatiles were removed under reduced pressure, and the resulting crude material was purified by silica gel chromatography using 2% ether in pentane as eluent to give desired product S2 in 65% to 70% yield.

Step 2. Deprotection of TBS group on nitrogen

Inside a glove box, a 50 mL flask was charged with S2 (680 mg, 2.89 mmol), a magnetic stir bar, and 5.0 mL ether. Then the flask was cooled down to –30 °C in the glove box freezer. TBAF (912 mg, 2.89 mmol) in 3.0 mL ether and was added dropwise to the stirred solution of S2 at room temperature inside the glove box. After 30 minutes, the reaction vessel was removed from the glovebox, and the volatiles were removed under reduce pressure. The remaining light yellow liquid in the flask was transferred to a separation funnel and diluted with 5.0 mL pentane and 5.0 mL degassed brine inside the glove box. The organic layer was separated and washed again with 5.0 mL degassed brine. The aqueous layers were combined and extracted three more times with 5.0 mL pentane each time. The combined organic layers were dried over MgSO4. Then, the organic layer was purified on the silica gel chromatography using 0% ~ 2% ether in pentane as eluent to give desired product NHBnPr and NHBiPr in 70% to 80% yield, respectively.

Spectral data for NHBnPr:

1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 7.88 (t, J=44.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (m, 1H), 7.27 (t, 1H, J= 7.2 Hz), 6.71 (d, J=11.2 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (t, J=6.5 Hz, 1H), 1.53 (m, 2H), 1.11 (t, J= 7.2 Hz, 2H), 0.96 (t, J= 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 143.1, 133.5, 129.7 (br), 109.5, 21.5 (br), 19.5, 17.0; 11B NMR (160MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 37.2; IR: 3379, 3018, 2953, 2927, 2867,1615, 1537, 1461, 1423, 1356, 1231, 1124, 1091, 9989, 786, 718, 617 cm-1; MS[APPI] calcd for C7H13NB[M+H+]: 122.1145, found 122.1139.

Spectral data for NHBiPr:

1H NMR (500MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 7.89 (t, J=44.6 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 1.40 (m, 1H), 1.09 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 143.5, 133.3, 109.6, 19.9, signals for carbon atoms attached to boron were not observed; 11B NMR (160 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 38.3; IR: 3415, 2953, 2929, 2857, 1537, 1463, 1252, 1049, 1004, 834, 779, 725, 695, 670 cm-1. MS[APPI] calcd for C7H13NB[M+ H+]: 122.1145, found 122.1141.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5.

General scheme and procedure for NHBnPr and NHBiPr.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (R01-GM094541). The authors thank Dr. Marek Domin, Dr. Peng Zhao, Dr. Marcus Fischer, and Dr. Hyelee Lee for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Footnotes relating to the title and/or authors should appear here.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: protein preparation, ITC experiments, NMR spectra of new compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Giustra ZX and Liu SY, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 1184–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Belanger-Chabot G, Braunschweig H and Roy DK, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem, 2017, 38, 4353–4368. [Google Scholar]; (c) Morgan MM and Piers WE, Dalton Trans, 2016, 45, 5920–5924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Campbell PG, Marwitz AJV and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2012, 51, 6074–6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Rombouts FJ, Tovar F, Austin N, Tresadern G and Trabanco AA, J. Med. Chem, 2015, 58, 9287–9295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vlasceanu A, Jessing M and Kilburn JP, Bioorg. Med. Chem, 2015, 23, 4453–4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marwitz AJV, Matus MH, Zakharov LN, Dixon DA and Liu S-Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2009, 48, 973–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrostowska A, Xu S, Lamm AN, Mazière A, Weber CD, Dargelos A, Baylère P, Graciaa A and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 10279–10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Fischer M, Shoichet BK and Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 12021–12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao P, Nettleton DO, Karki RG, Zecri FJ and Liu S-Y, ChemMedChem, 2017, 12, 358–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Liu Z, Wang G, Li Z and Wang R, J. Chem. Theory. Comput, 2008, 4, 1959–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fersht AR, Shi JP, Knill-Jones J, Lowe DM, Wilkinson AJ, Blow DM, Brick P, Carter P, Waye MM and Winter G, Nature, 1985, 314, 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao MH, J. Chem. Theory. Comput, 2006, 2, 863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Foloppe N, Fisher LM, Howes R, Kierstan P, Potter A, Robertson AG and Surgenor AE, J. Med. Chem, 2005, 48, 4332–4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mills JE and Dean PM, J Comput. Aided. Mol. Des, 1996, 10, 607–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Toth G, Bowers SG, Truong AP and Probst G, Curr. Pharm. Des, 2007, 13, 3476–3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For select examples in synthetic non-aqueous systems, see: (a) Desseyn HO, Perlepes SP, Clou K, Blaton N, Van der Veken BJ, Dommisse R and Hansen PE, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2004, 108, 5175–5182. [Google Scholar]; (b) West R, Whatley LS, Lee MKT and Powell DL, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1964, 86, 3227–3229. [Google Scholar]; (c) Berthelot M, Besseau F and Laurence C, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 1998, 925–931. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.(a) Krimmer SG and Klebe G, J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des, 2015, 29, 867–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsai C-J; Norel R; Wolfson HJ; Maizel JV; Nussinov R Encyclopedia of Life Science; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, 2001; doi: 10.1038/npg.els.0001343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For an overview, see: Cockroft SL and Hunter CA, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2007, 36, 172–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter PJ, Winter G, Wilkinson AJ and Fersht AR, Cell, 1984, 38, 835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horovitz A and Fersht AR, J. Mol. Biol, 1990, 214, 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camara-Campos A, Musumeci D, Hunter CA and Turega S, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131, 18518–18524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei BQ, Baase WA, Weaver LH, Matthews BW and Shoichet BK, J. Mol. Biol, 2002, 322, 339–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Eriksson AE, Baase WA, Wozniak JA and Matthews BW, Nature, 1992, 355, 371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Morton A, Baase WA and Matthews BW, Biochemistry, 1995, 34, 8564–8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perozzo R, Folkers G and Scapozza L, J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res, 2004, 24, 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klebe G, Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov, 2015, 14, 95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigurskjold BW, Anal. Biochem, 2000, 277, 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. It is noteworthy to mention that these estimated energetic values may also contain an additional electrostatic contribution between dipolar azaborine molecules and protein binding sites.

- 21.(a) Steiner T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2002, 41, 48–76. [Google Scholar]; (b) Harris KDM, Kariuki BM, Lambropoulos C, Philp D and Robinson JM, Tetrahedron, 1997, 53, 8599–8612. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merski M, Fischer M, Balius TE, Eidam O and Shoichet BK, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2015, 112, 5039–5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baggett AW, Liu S-Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 15259–15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.