Abstract

Glycosylation, or the addition of sugars to proteins, is a highly conserved protein modification defined by both the monosaccharide initially attached to the protein as well as the amino acid to which it is attached. O-linked glycosylation represents a diverse group of protein modifications occurring on the hydroxyl groups of serine and/or threonine residues. O-glycosylation can have wide-ranging effects on protein stability and function, which translate into crucial consequences at the organismal level. This review will summarize structural and biological insights into the major O-glycans formed within the secretory apparatus (O-GalNAc, O-Man, O-Fuc, O-Glc and extracellular O-GlcNAc) from studies in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Drosophila has many advantages for investigating these complex modifications, boasting reduced functional redundancy within gene families, reduced length/complexity of glycan chains and sophisticated genetic tools. Gaining an understanding of the normal cellular and developmental roles of these conserved modifications in Drosophila will provide insight into how changes in O-glycans are involved in human disease and disease susceptibilities.

Keywords: O-glycosylation, development, Drosophila, Notch, Tango

Major O-linked glycans in Drosophila

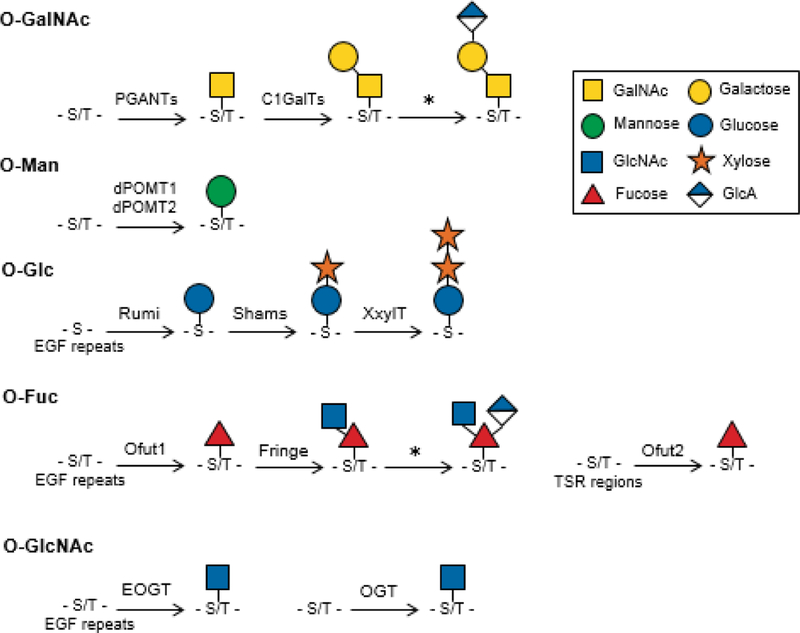

While the major types of O-glycans and the enzymes that generate them are conserved between Drosophila and mammals, the length and complexity (glycan composition and branching) tend to be reduced in Drosophila. A seminal study by the Tiemeyer lab characterized the major O-glycans (excluding glycosaminoglycans) present during Drosophila embryogenesis and in a developing organ [1]. Detailed mass spectrometric analysis characterized the predominant O-glycans to be the core 1 disaccharide (Galβ1,3GalNAc); the core 1 disaccharide modified with glucuronic acid (GlcA); a HexNAc monosaccharide (GalNAc or GlcNAc); and a fucose-based trisaccharide, all of which together constituted as much as 96% of the total O-glycans (Fig. 1). This study highlighted both structural similarities between Drosophila and mammalian O-glycans, as well as unique differences, including reduced glycan chain length and the use of GlcA in flies in place of sialic acid (found abundantly in mammals). Moreover, some glycan structures found suggested unique biological functions based on when and where they were present.

Figure 1.

Major O-glycans present in Drosophila melanogaster. The major O-glycans present in Drosophila melanogaster and the enzymes that catalyze their formation are shown. Symbols denoting each saccharide are shown in the legend. * denotes enzymes that are currently unknown/unconfirmed in this pathway. S, serine; T, threonine.

O-GalNAc

O-GalNAc (mucin-type O-glycosylation) is the major type of glycosylation found in the Drosophila embryo and one of the more abundant types of O-glycosylation within both mammals and Drosophila. (Other major O-glycans, such as O-linked xylose-derived glycans, which form the basis of diverse glycosaminoglycans, and cytoplasmic/nuclear O-GlcNAc will be covered in separate sections). While O-GalNAc is well-documented on mucins (conferring their unique structural and rheological properties), this protein modification has also been found on diverse secreted and membrane-bound proteins in Drosophila (and mammals) [2], indicating its potentially broad and complex influence over many cellular processes.

The initial addition of GalNAc through an α O-glycosidic linkage to the hydroxyl group of serine or threonine is catalyzed by a large family of evolutionarily-conserved enzymes known as the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases (ppGalNAc-Ts or GalNAc-Ts in mammals; PGANTs in Drosophila; EC 2.4.1.41) (Fig. 1). There are 20 family members in humans, 19 in mice and 10 in Drosophila, all of which are type II transmembrane proteins that reside in the Golgi apparatus. Many family members display unique spatial and temporal expression during Drosophila (and mammalian) development [3,4]. Moreover, certain family members exhibit unique substrate preferences that are dictated by 2 separate domains within these enzymes; a catalytic domain (consisting of a glycosyltransferase domain in which the active site lies) and a ricin-like lectin domain. Structural details of how these 2 domains coordinate the recognition and binding of substrates as well as the hierarchical addition of glycans, are discussed in another section (Polypeptide GalNAc-Ts: from redundancy to specificity).

The biological roles of O-GalNAc glycans have been challenging to decipher given the degree of redundancy built into the first committed step of biosynthesis as well as the hundreds of potential substrates that could be simultaneously affected. However, studies from Drosophila have demonstrated that at least 5 family members of the pgant family are essential for viability or influence viability [5–9]. Genetic ablation of individual pgants has demonstrated roles in the production, packaging and secretion of extracellular matrix components, resulting in defects in epithelial cell polarity [6,8]; loss of cell adhesion [10,11]; and changes in the progenitor cell niche, leading to aberrant cell proliferation [12]. Mechanistically, one family member (PGANT4) has been shown to influence secretion/secretory granule formation by glycosylating a conserved cargo receptor (Tango1) and protecting it from proteolysis [13]. This protective role of O-GalNAc is similar to that seen in mammals, where GALNT3 glycosylates the phosphaturic hormone FGF23, protecting it from proteolysis [14]. More recently, evidence has emerged that O-glycosylation of secretory proteins (cargo) is required for proper secretory granule morphology [15]. This study also demonstrates evidence for differential splicing of functional domains within these glycosyltransferases to alter substrate specificity [15], suggesting an even greater repertoire of enzymes catalyzing the initial transfer of O-linked GalNAc than the gene number would suggest. Given the complexity of the many enzymes involved in O-GalNAc addition, combined with the enormous number of potential substrates, studies in this tractable model system will be crucial to gain a fundamental understanding of the roles of this protein modification in vivo.

After the initial addition of GalNAc, the predominant modification involves the additional of Gal in a β1,3 linkage by another family of enzymes known as the core 1 galactosyltransferases (C1GalTs) (Fig. 1). While only 1 C1GalT exists in mammals (C1GalT1 or T-synthase), as many as 9 potential members exist in Drosophila [16], suggesting additional functional redundancy exists within this family as well. Genetic studies ablating 1 family member (C1GalT1) resulted in neurological phenotypes, including elongated ventral nerve cords and distorted brain hemispheres [17,18] (Table I). While substrates were not identified, there was evidence of disruptions in the extracellular matrix normally present in the nervous system.

Table I.

Developmental phenotypes associated with mutation or knockdown of genes encoding the enzymes involved in O-glycan biosynthesis in Drosophila

| Gene | Protein/Enzyme | Glycan formed | Mutant phenotypes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pgant3 | PGANT3 | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -decreased secretion of ECM components -loss of integrin-mediated cell adhesion resulting in wing blisters |

Zhang et al., 2008 Zhang et al., 2010 |

| pgant4 | PGANT4 | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -lethal during development -loss of secretory vesicles and secretion defects in digestive system |

Tran et al., 2012 Zhang et al., 2014 |

| pgant5 | PGANT5 | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -lethal during development -loss of gut acidification |

Tran et al., 2012 |

| pgant7 | PGANT7 | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -lethal during development | Tran et al., 2012 |

| pgant35A | PGANT35A | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -lethal during development -irregular formation of embryonic respiratory system -loss of cell polarity and diffusion barrier in respiratory system |

Ten Hagen and Tran, 2002 Schwientek et al., 2002 Tian and Ten Hagen, 2007 |

| pgant9 | PGANT9 | GalNAcα-O-S/T | -semi-lethal during development -loss of one splice variant (PGANT9B) causes abnormal morphology of secretory granules |

Tran et al., 2012 Ji and Samara et al., 2018 |

| C1GalTA | C1GalTA | Galß1,3GalNAcα-O-S/T | -elongated ventral nerve cord -distorted brain hemispheres |

Lin et al., 2008 Yoshida et al., 2008 |

| rotated abdomen (rt) | dPOMT1 | Manα-O-S/T | -semi-lethal during development -clockwise rotation of the abdominal segments -muscle developmental defects, abnormal synaptic transmission -decreased flying and climbing abilities -abnormal axonal connections of sensory neurons leading to abnormal muscle contractions and embryo torsion |

Martin-Blanco and Garcia-Bellido, 1996 Ichimiya et al., 2004 Lyalin et al., 2006 Haines et al.,2007 Wairkar et al., 2008 Ueyama et al., 2010 Baker et al., 2018 |

| twisted (tw) | dPOMT2 | Manα-O-S/T | -semi-lethal during development -clockwise rotation of the abdominal segments -muscle developmental defects -decreased flying and climbing abilities -abnormal axonal connections of sensory neurons leading to abnormal muscle contractions and embryo torsion |

Martin-Blanco and Garcia-Bellido, 1996 Ichimiya et al., 2004 Lyalin et al., 2006 Haines et al.,2007 Ueyama et al., 2010 Baker et al., 2018 |

| Eogt | EOGT | GlcNAcß-O-S/T on EGF repeats | -lethal during larval development -cuticle defects and irregular tracheal morphology -wing blisters and thorax vortex |

Sakaidani et al., 2011 Muller et al., 2013 |

| Ofut1 | Ofut1 | Fucα-O-S/T on EGF repeats | -lethal during development -reduction in Notch signaling leading to loss of wing tissue, thickened wing veins, rough eyes, additional notal macrochaetes, leg segment fusions |

Okajima and Irvine, 2002 Okajima et al., 2005 Okajima et al., 2008 |

| fng | Fringe | GlcNAcß1,3Fucα-O-S/T on EGF repeats | -alterations in Notch signaling by regulating Notch-ligand interactions -defects in wing formation -defects in eye development |

Irvine and Wieschaus, 1994 Cho and choi, 1998 Correia et al., 2003 LeBon et al., 2014 |

| Ofut2 | Ofut2 | Fucα-O-S/T on TSR regions | -decreased TSR specific O-fucosyltransferase activity in S2 cells | Luo et al., 2006 |

| rumi | Rumi | Glcß-O-S on EGF repeats | -defects in Notch folding and signaling leading to loss of bristles, defects in wing, eye and leg development -highly penetrant rhabdomere attachment phenotype |

Acar et al., 2008 Haltom et al., 2014 |

| shams | Shams | Xylα1,3Glcß-O-S on EGF repeats | -increase in Delta-mediated Notch signaling leading to abnormal wing vein formation and head bristle development |

Lee et al., 2013 Lee et al., 2017 |

| Xxylt | Xxylt | Xylα1,3Xylα1,3Glcß-O-S on EGF repeats | -changes in Notch signaling only in sensitized genetic backgrounds |

Lee et al., 2013 Haltom and Jafar-Nejad, 2015 Pandey et al., 2018 |

O-Man

The addition of an O-linked mannose to the hydroxyl group of serines or threonines in Drosophila is catalyzed by 2 protein O-mannosyltransferases known as dPOMT1 and dPOMT2, encoded by the genes rotated abdomen (rt) and twisted (tw) respectively [19–21] (Fig. 1). These enzymes are transmembrane proteins that reside in the ER and are highly homologous to the mammalian orthologs responsible for O-mannosylation [19]. Both genes are required for O-mannosylation in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that they function in a heteromeric complex within the ER [19]. Interestingly, while mammalian O-mannose is usually extended by the addition of other sugars, Drosophila O-mannose exists on proteins as a monosaccharide [1].

O-mannosylation is essential for viability in Drosophila (Table I) as loss of both rt and tw simultaneously is lethal [19]. Loss of either gene results in a decrease in viability and surviving adults display a 90° clockwise rotation of their abdominal segments [19–22]. More detailed characterization shows defects in muscle attachment and architecture [23,24], as well as alterations in the neuromuscular junction [25]. Unlike O-GalNAc glycosylation, only a small number of targets have been identified for O-mannose glycosylation, the primary one being the transmembrane protein dystroglycan (Dg) [23], which is part of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC) that has been shown to be required for the proper linkage of the extracellular matrix to the inner cytoskeleton of the cell. Defects in components of the DGC and the enzymes that modify it (including human POMT1 and POMT2) are known to be responsible for human muscular dystrophies [26], which are also characterized by muscle and neurological phenotypes similar to those seen in Drosophila. Additional recent work in Drosophila has suggested a role for rt and tw within the sensory neurons during early development to establish proper muscle contractions and body posture [27]. Interestingly, these phenotypes are not mimicked by loss of Dg, suggesting that other biologically important targets for O-mannosylation that coordinate muscle contraction and nervous system feedback remain to be discovered [27].

O-Fuc

Notch signaling is an essential, conserved pathway that controls cell-cell communication and cell fate decisions during animal development and a number of types of glycosylation have been found to regulate it, including O-linked fucose [28]. The Notch receptor, a transmembrane protein on the surface of cells, binds to ligands (Delta or Serrate) and then undergoes a coordinated series of proteolytic cleavages leading to the release of its intracellular domain, which can then travel to the nucleus and regulate the transcriptional activity of many genes [28]. Thus, factors that regulate Notch receptor or ligand synthesis, stability, trafficking, interactions or the downstream cleavage events can have profound effects on tissue homeostasis and development. Interestingly, both Notch signaling and the glycosyltransferases that modulate it were first discovered in Drosophila.

The addition of O-linked fucose to serine or threonine within the EGF repeats of Notch or its ligands occurs through the action of the O-fucosyltransferase Ofut1 (Pofut1 in mammals) [29,30](Fig. 1). Ofut1 (encoded by the Ofut1 gene) is a soluble ER-localized enzyme that recognizes the consensus sequence C2-X-X-X-X-T/S-C3. The addition of fucose by Ofut1 is thought to regulate Notch signaling by affecting ligand binding [31]. Loss of Ofut1 resulted in lethality during development and phenotypes indicative of loss of Notch signaling (Table I). Additionally, there is also evidence in Drosophila suggesting a role for Ofut1 as a chaperone independent of its enzymatic activity [32,33]. However, a non-enzymatic role for the mammalian Pofut1 has not been found [28]. The O-fucose is further elaborated by the addition of GlcNAc by the Golgi-localized β1,3 N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase known as Fringe. The fng gene was the first example of a genetically well-characterized modulator of Notch signaling that was found to encode a glycosyltransferase [34,35]. Fringe-mediated elongation of O-fucose influences Notch signaling by enhancing the binding of one ligand (Delta) while inhibiting the binding of another (Serrate) [31,36–39].

Another O-fucosyltransferase, known as Ofut2, exists in Drosophila and adds fucose to thrombospondin type 1 repeats, which are found in many transmembrane and secreted proteins [40] (Fig. 1). Its function in vivo in Drosophila is currently unknown.

O-Glc

Work in Drosophila identified another glycosyltransferase Rumi (a member of the GT90 family) that also modifies the extracellular region of Notch to regulate signaling. The gene rumi encodes an ER-localized, soluble O-glucosyltransferase (Poglut1 in mammals) that adds O-linked glucose (Glc) to serine residues within the consensus sequence C1-X-S-X-P/A-C2 of the EGF repeats (Fig. 1). rumi was identified in a screen for regulators of sensory organ development. Mutations in rumi resulted in decreased glucosylation of Notch and a reduction in Notch signaling [41]. Upon loss of rumi, Notch accumulated intracellularly and also failed to undergo proper cleavage at the cell membrane after ligand binding [41]. Studies in Drosophila have suggested that the loss of Rumi influences Notch folding/conformation, thus affecting its ability to undergo regulated cleavage after ligand binding. Additional work in Drosophila suggests that O-glucosylation by Rumi is also required for proper folding and stability of a secreted protein (Eyes shut) that is involved in proper photoreceptor organization in the eye [42]. Structural and biochemical studies of Poglut1 and mammalian EGF repeats further support a role for O-Glc glycans in the stabilization of EGF repeats to allow proper folding [43].

O-Glc can be further modified by the addition of xylose in an α linkage, through the action of the glucoside xylosyltransferase Shams (GXYLT1/2 in mammals) (Fig. 1). shams mutants have phenotypes indicative of Notch gain-of-function phenotypes, suggesting that xylose attached to glucose on Notch negatively regulates Notch signaling. Experimental evidence suggests that xylose may alter the cell surface expression of Notch in certain tissues [44]. However, in other instances Shams appears to affect the ability of Notch to bind Delta expressed on a neighboring cell (trans-Delta ligands) while not affecting its binding to ligands expressed from the Notch-expressing cell (cis-ligands). These studies suggest that the addition of xylose to the O-Glc on Notch regulates the balance of Notch activation occurring by trans-ligands relative to its inhibition by cis-ligands [45]. The mechanism whereby xylose on Notch would differentially affect binding to Delta in trans versus cis is currently unknown.

Finally, a second xylose can be added to Xylα1,3Glc present on EGF repeats through the action of a xyloside xylosyltransferase encoded by the Xxylt gene (CG11388) in Drosophila (XXYLT1 in mammals) [46] (Fig. 1). Loss of this gene results in phenotypes only when combined with other genetic modifiers of Notch signaling, suggesting that it functions primarily in fine-tuning this signaling pathway.

O-GlcNAc (extracellular)

While the presence of O-linked GlcNAc is well-established on nuclear, cytoplasmic and mitochondrial proteins, the addition of an O-linked GlcNAc to secreted and membrane proteins is a more recent discovery. EOGT (encoded by the gene Eogt) is a soluble ER-resident glycosyltransferase that transfers GlcNAc to serine or threonine within the consensus sequence C5-X-X-G-X-T/S-G-X-X-C6 in EGF repeating domains of a number of proteins [47–49]) (Fig. 1). Loss of Eogt throughout the animal results in larval lethality, while tissue-specific loss within the wing causes wing blisters [49]. One of the major proteins glycosylated by EOGT is Dumpy (Dp), a large apically localized membrane-anchored protein that is involved in the maintenance of cell-extracellular matrix interactions (Table I). Additionally, O-GlcNAc has been found in the EGF repeats of Notch and the Notch ligands, Delta and Serrate [48]. Genetic interaction studies revealed that the loss of Eogt could be partially rescued by loss of one allele of Notch or its ligands [48], suggesting that Eogt may be involved in downregulating Notch signaling. Additionally, genetic interactions were also noted between Eogt and genes involved in pyrimidine metabolism. The details of how levels of EOGT and Notch may be connected to uracil production remain to be elucidated but suggest that this enzyme may serve to modulate levels of nucleotide sugars within the ER.

Future outlook

Alterations in O-linked glycosylation are associated with many human diseases and syndromes, highlighting their importance in biomedicine. However, a fundamental understanding of how these conserved protein modifications affect protein structure, stability and/or function, combined with insight into how these alterations in protein function translate into cellular and organismal phenotypes is essential for developing well-informed, effective strategies for disease diagnosis and treatment. To that end, the sophisticated genetic and molecular tools unique to Drosophila have both identified previously unknown O-glycans and accelerated our understanding of their complex and diverse functions. Future work in this model organism will continue to provide essential mechanistic insights into the biological roles of these conserved protein modifications.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of our laboratory and the many members of the community who have contributed to the work mentioned herein. Our laboratory is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIDCR, NIH (Z01-DE-000713 to K.G.T.H.).

Abbreviations

The abbreviations used are:

- ppGalNAc-T or GalNAc-T or PGANT

UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase

- Man

mannose

- Fuc

fucose

- Glc

glucose

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- Gal

galactose

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- GlcA

glucuronic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aoki K, Porterfield M, Lee SS, Dong B, Nguyen K, McGlamry KH, Tiemeyer M: The diversity of O-linked glycans expressed during Drosophila melanogaster development reflects stage- and tissue-specific requirements for cell signaling. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:30385–30400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwientek T, Mandel U, Roth U, Muller S, Hanisch FG: A serial lectin approach to the mucin-type O-glycoproteome of Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells. Proteomics 2007, 7:3264–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingsley PD, Hagen KG, Maltby KM, Zara J, Tabak LA: Diverse spatial expression patterns of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase family member mRNAs during mouse development. Glycobiology 2000, 10:1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian E, Ten Hagen KG: Expression of the UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family is spatially and temporally regulated during Drosophila development. Glycobiology 2006, 16:83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwientek T, Bennett EP, Flores C, Thacker J, Hollmann M, Reis CA, Behrens J, Mandel U, Keck B, Schafer MA, et al. : Functional conservation of subfamilies of putative UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases in Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, and mammals. One subfamily composed of l(2)35Aa is essential in Drosophila. J Biol Chem 2002, 277:22623–22638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ten Hagen KG, Tran DT: A UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase is essential for viability in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem 2002, 277:22616–22622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ten Hagen KG, Tran DT, Gerken TA, Stein DS, Zhang Z: Functional characterization and expression analysis of members of the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:35039–35048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian E, Ten Hagen KG: A UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase is required for epithelial tube formation. J Biol Chem 2007, 282:606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran DT, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Tian E, Earl LA, Ten Hagen KG: Multiple members of the UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family are essential for viability in Drosophila. J Biol Chem 2012, 287:5243–5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Tran DT, Ten Hagen KG: An O-glycosyltransferase promotes cell adhesion during development by influencing secretion of an extracellular matrix integrin ligand. J Biol Chem 2010, 285:19491–19501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Hagen KG: A mucin-type O-glycosyltransferase modulates cell adhesion during Drosophila development. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:34076–34086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Turner B, Ribbeck K, Ten Hagen KG: Loss of the mucosal barrier alters the progenitor cell niche via Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling. J Biol Chem 2017, 292:21231–21242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Syed ZA, van Dijk Hard I, Lim JM, Wells L, Ten Hagen KG: O-glycosylation regulates polarized secretion by modulating Tango1 stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:7296–7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topaz O, Shurman DL, Bergman R, Indelman M, Ratajczak P, Mizrachi M, Khamaysi Z, Behar D, Petronius D, Friedman V, et al. : Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet 2004, 36:579–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji S, Samara NL, Revoredo L, Zhang L, Tran DT, Muirhead K, Tabak LA, Ten Hagen KG: A molecular switch orchestrates enzyme specificity and secretory granule morphology. Nat Commun 2018, 9:3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller R, Hulsmeier AJ, Altmann F, Ten Hagen K, Tiemeyer M, Hennet T: Characterization of mucin-type core-1 beta1–3 galactosyltransferase homologous enzymes in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS J 2005, 272:4295–4305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin YR, Reddy BV, Irvine KD: Requirement for a core 1 galactosyltransferase in the Drosophila nervous system. Dev Dyn 2008, 237:3703–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida H, Fuwa TJ, Arima M, Hamamoto H, Sasaki N, Ichimiya T, Osawa K, Ueda R, Nishihara S: Identification of the Drosophila core 1 beta1,3-galactosyltransferase gene that synthesizes T antigen in the embryonic central nervous system and hemocytes. Glycobiology 2008, 18:1094–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichimiya T, Manya H, Ohmae Y, Yoshida H, Takahashi K, Ueda R, Endo T, Nishihara S: The twisted abdomen phenotype of Drosophila POMT1 and POMT2 mutants coincides with their heterophilic protein O-mannosyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem 2004, 279:42638–42647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyalin D, Koles K, Roosendaal SD, Repnikova E, Van Wechel L, Panin VM: The twisted gene encodes Drosophila protein O-mannosyltransferase 2 and genetically interacts with the rotated abdomen gene encoding Drosophila protein O-mannosyltransferase 1. Genetics 2006, 172:343–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Blanco E, Garcia-Bellido A: Mutations in the rotated abdomen locus affect muscle development and reveal an intrinsic asymmetry in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93:6048–6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura N, Stalnaker SH, Lyalin D, Lavrova O, Wells L, Panin VM: Drosophila Dystroglycan is a target of O-mannosyltransferase activity of two protein O-mannosyltransferases, Rotated Abdomen and Twisted. Glycobiology 2010, 20:381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haines N, Seabrooke S, Stewart BA: Dystroglycan and protein O-mannosyltransferases 1 and 2 are required to maintain integrity of Drosophila larval muscles. Mol Biol Cell 2007, 18:4721–4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueyama M, Akimoto Y, Ichimiya T, Ueda R, Kawakami H, Aigaki T, Nishihara S: Increased apoptosis of myoblasts in Drosophila model for the Walker-Warburg syndrome. PLoS One 2010, 5:e11557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wairkar YP, Fradkin LG, Noordermeer JN, DiAntonio A: Synaptic defects in a Drosophila model of congenital muscular dystrophy. J Neurosci 2008, 28:3781–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheikh MO, Halmo SM, Wells L: Recent advancements in understanding mammalian O-mannosylation. Glycobiology 2017, 27:806–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker R, Nakamura N, Chandel I, Howell B, Lyalin D, Panin VM: Protein O-Mannosyltransferases Affect Sensory Axon Wiring and Dynamic Chirality of Body Posture in the Drosophila Embryo. J Neurosci 2018, 38:1850–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvey BM, Haltiwanger RS: Regulation of Notch Function by O-Glycosylation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018, 1066:59–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okajima T, Irvine KD: Regulation of notch signaling by o-linked fucose. Cell 2002, 111:893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panin VM, Shao L, Lei L, Moloney DJ, Irvine KD, Haltiwanger RS: Notch ligands are substrates for protein O-fucosyltransferase-1 and Fringe. J Biol Chem 2002, 277:29945–29952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okajima T, Xu A, Irvine KD: Modulation of notch-ligand binding by protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 and fringe. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:42340–42345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okajima T, Reddy B, Matsuda T, Irvine KD: Contributions of chaperone and glycosyltransferase activities of O-fucosyltransferase 1 to Notch signaling. BMC Biol 2008, 6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okajima T, Xu A, Lei L, Irvine KD: Chaperone activity of protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 promotes notch receptor folding. Science 2005, 307:1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruckner K, Perez L, Clausen H, Cohen S: Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-Delta interactions. Nature 2000, 406:411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moloney DJ, Panin VM, Johnston SH, Chen J, Shao L, Wilson R, Wang Y, Stanley P, Irvine KD, Haltiwanger RS, et al. : Fringe is a glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch. Nature 2000, 406:369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho KO, Choi KW: Fringe is essential for mirror symmetry and morphogenesis in the Drosophila eye. Nature 1998, 396:272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Correia T, Papayannopoulos V, Panin V, Woronoff P, Jiang J, Vogt TF, Irvine KD: Molecular genetic analysis of the glycosyltransferase Fringe in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100:6404–6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irvine KD, Wieschaus E: fringe, a Boundary-specific signaling molecule, mediates interactions between dorsal and ventral cells during Drosophila wing development. Cell 1994, 79:595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeBon L, Lee TV, Sprinzak D, Jafar-Nejad H, Elowitz MB: Fringe proteins modulate Notch-ligand cis and trans interactions to specify signaling states. Elife 2014, 3:e02950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo Y, Koles K, Vorndam W, Haltiwanger RS, Panin VM: Protein O-fucosyltransferase 2 adds O-fucose to thrombospondin type 1 repeats. J Biol Chem 2006, 281:9393–9399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Takeuchi H, Rajan A, Ibrani D, Rana NA, Pan H, Haltiwanger RS, Bellen HJ: Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell 2008, 132:247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haltom AR, Lee TV, Harvey BM, Leonardi J, Chen YJ, Hong Y, Haltiwanger RS, Jafar-Nejad H: The protein O-glucosyltransferase Rumi modifies eyes shut to promote rhabdomere separation in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 2014, 10:e1004795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeuchi H, Yu H, Hao H, Takeuchi M, Ito A, Li H, Haltiwanger RS: O-Glycosylation modulates the stability of epidermal growth factor-like repeats and thereby regulates Notch trafficking. J Biol Chem 2017, 292:15964–15973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee TV, Sethi MK, Leonardi J, Rana NA, Buettner FF, Haltiwanger RS, Bakker H, Jafar-Nejad H: Negative regulation of notch signaling by xylose. PLoS Genet 2013, 9:e1003547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee TV, Pandey A, Jafar-Nejad H: Xylosylation of the Notch receptor preserves the balance between its activation by trans-Delta and inhibition by cis-ligands in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 2017, 13:e1006723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandey A, Li-Kroeger D, Sethi MK, Lee TV, Buettner FFR, Bakker H, Jafar-Nejad H: Sensitized genetic backgrounds reveal differential roles for EGF repeat xylosyltransferases in Drosophila Notch signaling. Glycobiology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Matsuura A, Ito M, Sakaidani Y, Kondo T, Murakami K, Furukawa K, Nadano D, Matsuda T, Okajima T: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine is present on the extracellular domain of notch receptors. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:35486–35495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller R, Jenny A, Stanley P: The EGF repeat-specific O-GlcNAc-transferase Eogt interacts with notch signaling and pyrimidine metabolism pathways in Drosophila. PLoS One 2013, 8:e62835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakaidani Y, Nomura T, Matsuura A, Ito M, Suzuki E, Murakami K, Nadano D, Matsuda T, Furukawa K, Okajima T: O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine on extracellular protein domains mediates epithelial cell-matrix interactions. Nat Commun 2011, 2:583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]