Abstract

An electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) imaging system has been custom built for use in pre-clinical and, potentially, clinical studies. Commercial standalone modules have been used in the design that are MATLAB-controlled. The imaging system combines digital and analog technologies. It was designed to achieve maximum flexibility and versatility and to perform standard and novel user-defined experiments. This design goal is achieved by frequency mixing of an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) output at the intermediate frequency (IF) with a constant source frequency (SF). Low noise SF at 250, 750, and 1000 MHz are available in the system. A wide range of frequencies from near-baseband to L-band can be generated as a result. Two-stage downconversion at the signal detection side is implemented that enables multi-frequency EPR capability. In the first stage, the signal frequency is converted to IF. A novel AWG-enabled digital auto-frequency control method that operates at IF is described that is used for automatic resonator tuning. Quadrature baseband EPR signal is generated in the second downconversion step. The semi-digital approach of mixing low-noise frequency sources with an AWG permits generation of arbitrary excitation patterns that include but are not limited to frequency sweeps for resonator tuning and matching, continuous-wave, and pulse sequences. Presented in this paper is the demonstration of rapid scan (RS) EPR imaging implemented at 800 MHz. Generation of stable magnetic scan waveforms is critical for the RS method. A digital automatic scan control (DASC) system was developed for sinusoidal magnetic field scans. DASC permits tight control of both amplitude and phase of the scans. A surface loop resonator was developed using 3D printing technology. RS EPR imaging system was validated using sample phantoms. In vivo imaging of a breast cancer mouse model is demonstrated.

Keywords: Rapid scan EPR, EPR imaging, digital EPR, in vivo imaging, free radical, pre-clinical EPR, oximetry

1. Introduction

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and imaging provide valuable functional information in pre-clinical studies [1–16]. Clinical applications of EPR have demonstrated the importance of direct oxygen measurements in tumors and tissues using continuous-wave (CW) EPR spectroscopy [17–19]. Two standard EPR methods, CW and pulsed, have been used for in vivo spectroscopy and imaging. Each of the two methods has its advantages and limitations. The pulsed method provides superior sensitivity when electron relaxation times are much longer compared to instrumental dead-time [20]. In this method, resonance rotation of the magnetization vector into the xy-plane maximizes echo and free induction decay (FID) signal intensities. However, spin relaxation processes during experimental dead-time may negate this advantage. Pulsed EPR imaging often is restricted by the pulse excitation bandwidth, which limits the spectral width of projections. Pulsed gradients may be used to overcome the bandwidth limitations [21]. The result is a constraint on the maximum sample size and/or spatial resolution. In comparison, CW modality is not bandwidth-limited, and measurements of wide multi-line spectra are permitted. Dead-time-free CW EPR is the method of choice when spin probes with relatively short relaxation times are used. However, the spatial resolution of images may be limited due to low signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) of high-gradient projections. SNR of the first-derivative CW spectra decreases proportionally to the gradient strength squared. In addition, CW EPR has an inherent sensitivity threshold due to constraints on power, amplitude modulation and frequency. Increasing any of these parameters above a certain limit causes spectral distortions.

Various types of CW EPR experiments have been proposed in which rapid scanning of the magnetic field have been used to reduce the experimental time and/or noise [22–24]. A sinusoidal rapid scan (RS) method [5, 25–32] was recently developed that combines the standard CW spin excitation with broadband detection of transient FID-like EPR signals. This method is implemented in the EPR imaging system currently described. RS EPR occupies an important niche between the traditional first derivative CW and pulsed EPR. Signal intensity enhancement is achieved using rapid passage regime in which the spins system experiences a short excitation pulse due to the rapid passage through the resonance conditions. Algorithms have been developed that transform transient signals into absorption EPR spectra [25, 33]. In RS EPR, the magnetic field scan encompasses the entire spectrum. The EPR absorption spectrum is measured, the intensity of which is inversely proportional to the gradient strength. Rapid passage through resonance permits the use of higher power without saturating the spin system [34]. This results in an improved SNR. Depending on the sample and resonator bandwidth, enhancement of up to two orders of magnitude in sensitivity can be achieved [29].

In this manuscript, we describe an EPR imaging system designed and constructed at West Virginia University. The use of this system has been previously reported in peer-reviewed publications, including real-time EPR co-imaging with positron emission tomography [35], demonstration of a novel RS EPR algorithm [25], and enzyme activity imaging [36]. In these papers, only a limited description of the EPR imager was provided. In addition, various parts of the system have been further developed and improved.

This manuscript describes the EPR system and its RS EPR imaging capabilities in detail. Experiments, including in vivo, were done at approximately 800 MHz. This frequency is considerably higher compared to that used in the previously reported RS EPR imager at 250 MHz [5]. Recently, a RS imager at 700 MHz was reported by the Eaton group [32]. However, animal experiments have yet to be demonstrated. The design described in this study differs from the previously reported instruments on several levels. First, we implemented a semi-digital approach for RS EPR method that can also be implemented for CW, pulsed, and emerging fieldmodulated pulse EPR techniques [37, 38] in the broad frequency range of 100 – 1250 MHz. The semi-digital method permits the use of high-resolution low-noise low-cost arbitrary waveform generators (AWG) that provide sufficient bandwidth. Direct generation of EPR radiofrequency (RF) simplifies overall design [39] but may not be practical, especially at high frequencies. Second, an innovative digital automatic frequency control (DAFC) system is introduced. Enabled by the AWG, DAFC periodically sweeps RF to find and lock on to the frequency that provides the best resonator coupling (minimum power reflection). Third, a digital automatic scan control (DASC) system is presented that automatically corrects the amplitude and phase of magnetic field scans. DASC permits a high degree of reproducibility and temporal stability of the magnetic scan waveform, which is essential for RS deconvolution [25, 33]. Fourth, a surface loop resonator was developed for RS EPR imaging of breast tumors. A resonator-supporting structure was 3D printed that reduced the amount of metal near the imaging volume. Fifth, in comparison with commercial closed-source EPR instruments, our semi-digital design is modular with many components available for purchase from vendors. These modules are stand-alone instruments that come with manufacturer warranties, engineering support, and remote-control software with MATLAB (MathWorks) code examples. As a result, our system has a low cost of maintenance and is easily upgradable. Using MATLAB for both hardware controls and data processing is convenient. This high-level language is evolving, and the list of supported instruments is constantly growing. The code can be easily shared and modified. The commonly used EasySpin EPR simulation package can be integrated into the MATLAB-based imaging software.

The RS EPR imager described here has been used for in vivo measurements in a mouse model of breast cancer, where oxygen mapping is demonstrated. Results from this in vivo study will be reported in the future.

2. EPR Imaging System

2.1. Design concept

The imaging system was designed as an open experimental platform that can be expanded to include various experimental methods, including non-EPR co-imaging modalities [35]. A modular approach to the design was used. Most of the modules in the system are commercially available standalone instruments that are remotely controlled from a personal computer using MATLAB. These off-the-shelf instruments come with full support from the vendors that include consulting, modifiable code examples and a warranty. As a result, the service cost is significantly reduced. Individual RF elements, such as amplifiers and frequency mixers, are connected into functional units using coaxial cables with minimum use of printed circuit boards. The modular approach makes it relatively easy to assemble a functional EPR system. The designs can be shared, reproduced and improved by other laboratories. 3D printing technology was used to build various parts of the imaging system. Rapid scan coils, enclosure for resonating capacitors, phantoms and various structural supports were manufactured in-house using available Form2 (Formlabs, MA), M3 (MakerGear, OH), and Fusion3 (Fusion3 −3D printers, NC) 3D printers. Free OpenSCAD software was used for 3D model design. Digital models can be modified, reprinted, and shared with other researches for further improvement and adaptation.

Only RS EPR implementation is reported in this manuscript; however, the system will be upgraded to perform conventional CW, multi-harmonic CW [40], and both standard and field-modulated [37, 38] pulsed experiments. This upgrade is at the “work-in-progress” stage. The schematics of the current system is shown in Fig. 1. More detailed descriptions of the separate units are provided below in the manuscript.

Fig. 1.

EPR imaging system schematics. The RF unit consists of a multi-frequency source that outputs phase-locked continuous-wave signals at 250 MHz, 750 MHz, 1000 GHz, and a 10 MHz reference signal. In the current EPR system, AWG output is upconverted by mixing with 750 MHz to generate EPR excitation. Reflection from the resonator signal is downconverted back to IF (stage one). The IF signal is used for resonator tuning, both manual and automatic (DAFC). EPR detection at the baseband is achieved by the second down-conversion step. The magnetic field unit controls the DC field, gradients, and rapid scan field. A digital feedback scan control system DASC ensures the stability of the amplitude and phase of the magnetic scan waveform. Both DASC and DAFC run as two independent MATLAB batch jobs in the background. All other controls and data processing are achieved through locally written MATLAB code.

2.2. Radiofrequency unit

2.2.1. Up-conversion to generate EPR frequency

Figure 1 shows the schematics of the RF unit that was designed to permit EPR operation in a wide range of frequencies. This can be achieved by mixing the frequencies of low noise constant sources (250, 750, 1000 MHz) with an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) output. Phase noise values at 10 kHz offset of these constant sources are −163, −152, and −149 dBc/Hz at respectively. The multi-frequency source unit was custom assembled by Wenzel Associates Inc. 10 MHz reference (−165 dBc/Hz at 10 kHz) is provided for clock-synchronization with external devices. Frequency mixing with a Keysight 33622A AWG and one of the RF sources provides up to ± 200 MHz bandwidth around the selected frequency (e.g., 750 ± 200 MHz). Although the specified bandwidth for this AWG is 120 MHz, in practice 200 MHz signals can be generated at power levels sufficient for reliable frequency mixing. At this frequency, the AWG will output a waveform with exactly five points per cycle at the maximum sampling rate of 1 GS/s. Due to the low sampling count, attenuated high frequency harmonics are generated that can be easily suppressed using a low-pass filter. The AWG internal clock is externally synchronized with the ultra-low noise 10 MHz reference as shown in Fig. 1. The 250, 750, 1000 MHz frequencies are synchronized with the same 10 MHz reference clock. The central carrier frequency of the upconverted RF waveforms can be controlled either by changing the AWG sampling clock or by changing the AWG waveform. The former method is considerably faster. The radiofrequency of interest is produced as the result of frequency mixing the constant source frequency (SF) with an intermediate frequency, IF, generated by the AWG:

| (1) |

In Eq. (1), the maximum clock rate for Keysight 33622A is clockmax = 1 GS/s and fmax is the AWG frequency at maximum sampling rate. By changing the AWG sampling clock, a desired RF frequency can be generated. In the experiments described below, SF=750MHz (see Fig. 1) and the working frequency range of the RS EPR imager is 783–825 MHz, defined by the CBP-804F+ (Minicircuits) bandpass filter (BPF). This filter was ordered in the SMA-connectorized form (Minicircuits TB-693+). The frequency range can be changed using a different filter. For example, SF-IF frequency can be used instead of the SF+IF component. It is important to note that no mixer is perfect, and SF leaks into the RF output channel. We used a ZFM-4H-S+ (Minicircuits) mixer that is specified to have about 40 dB of isolation within the frequency range of interest. Despite the substantial attenuation of the leakage, it may have sufficient intensity to interfere with the detected EPR signal. An additional filtering is required, which can be achieved by the use of a narrow-banded notch filter. In our design, a filtering stage was added at the detection side. The CBP-804F+ filter is connected to the output of the first-stage low noise amplifier (LNA) (Mini-circuits ZX60-P103LN+, 50–3000MHz). The filtered RF signal is amplified using an LNA (PHA-13HLN+, Minicircuits), shown as A2 in Fig.1, that delivers approximately 28 dBm of excitation power. The LNA was ordered in the form of an evaluation board TB-969–13HLN+ (Minicircuits). Instead of a commonly implemented circulator, a 14 dB coupler (Mini-circuits ZADC-17–14HP-S) is used to isolate the incident RF wave from the resonator reflection signal, where power is applied to the coupling output port. The coupler is shown as C14 in Fig.1. In this design, 14 dBm of power is absorbed by the coupler and 14 dBm of power is available for spin excitation. In addition to the excitation/detection decoupling function, the 50 Ohm coupler protects the exaction amplifier from back-reflection that may occur due to an impedance mismatching. The 14 dBm excitation power is sufficient for the experiments with trityl radicals that have narrow EPR spectra and low saturation thresholds, while imaging of nitroxides will require more power. The advantage of a coupler-based design is the lack of magnetic parts and the relatively broadband range of operation (500 – 1350 MHz) and directivity of 30 dB in the region of interest. The first stage LNA amplifier (A2 in Fig. 1) can be connected directly to the coupler port. A shielded assembly of the resonator, coupler and LNAs can be placed inside the magnet (see Fig.2 and Fig.3). The result is the elimination of intermediate cables and, therefore, a signal loss reduction.

Fig. 2.

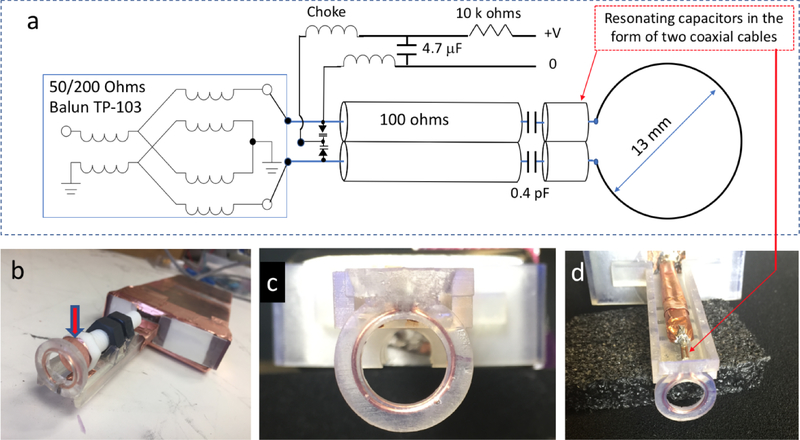

Surface loop resonator schematics (a) and photos (b, c, and d). The inductance of a copper loop (13 mm) is resonated by a capacitor in the form of two soldered coaxial cables. Circuit matching is achieved by two varactors. Broadband transformer balun is used to reject the common mode signal. In (b) a Teflon bolt covered with a thin copper film (indicated by the arrow) can be used for manual resonance frequency adjustments. Enclosed in a 3D printed support structure, the copper loop is shown in (c, d). (d) demonstrates paired coaxial cables (OD =1.2 mm) that act as a resonating capacitor for the resonator loop inductance.

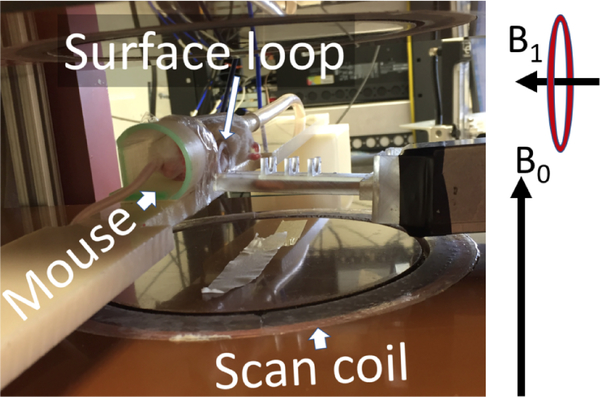

Fig. 3.

The rapid scan coils, resonator, and mouse bed are visible inside the permanent magnet. The directions of the constant magnetic field produced by the magnet and RF fields generated by the surface coil are denoted by B0 and B1 vectors, respectively.

2.2.2. Two-step down-conversion

Two LNAs, indicated jointly as A2 in Fig.1, (Mini-circuits ZX60-P103LN+, 50–3000MHz, noise figure ≈ 0.5 dB at 800 MHz) were connected in series to the coupler. Each LNA provides about 14 dB of gain, so the total gain of A2 is approximately 28 dB. ZX60-P103LN+ has a maximum rating of 25 dBm of input power. As a result, it is well protected from damage by excessive RF power at the input that may occur during in vivo measurements. Animal motion may cause substantial resonator detuning and, as a result, strong reflection. The output of ZX60-P103LN+ is saturated (1dB compression) at about 22 dBm, so that the second LNA is protected as well.

After LNA amplification, the signal is bandpass-filtered to remove the above-mentioned 750 MHz leakage components and down-converted to the baseband in two stages. The first stage is frequency-mixing with constant SF=750 MHz that is followed by low-pass filtering to suppress the SF+IF (leakage) and 2SF+IF components. The result of mixing and filtering is a signal at IF carrier frequency. This signal has EPR and non-EPR RF reflection components. When the resonator is not well-tuned, non-EPR reflection is substantially stronger than the EPR signal. In tuning mode, the AWG outputs a frequency scan in a range determined by the user to find the resonance frequency. This sweep signal is upconverted (described above), transferred to the resonator, down-converted back to IF (the first down-conversion stage) and digitized. The non-EPR reflection is Fourier transformed and analyzed to give a numeric value of the resonance frequency. This value corresponds to the reflection minimum. Digitization of the IF signals is done using a Gage CSE161G4 PCIe card. In tuning mode, the software displays a Fourier domain tuning pattern, and the experimenter manually adjusts the voltage value that changes the capacitances of a pair of matching varactors (see Fig. 2a). The goal of this procedure is to minimize RF reflection. After the matching is accomplished, the system can be switched to operation continuous-wave (CW) mode. The software automatically finds and sets the resonance frequency. During CW operation the reflection levels at IF are constantly monitored.

Besides tuning and CW, a third AWG-enabled DAFC mode is available to the system user. The digital auto-frequency control operates at IF frequency. In DAFC mode, the first AWG channel outputs a complex waveform consisting of a very short (10 – 100 μs) frequency sweep followed by a 10 – 100 ms CW waveform. The system continuously alternates between tuning and CW regimes at a rate of 10 – 100 Hz. A background MATLAB job periodically adjusts the resonance frequency. This method ensures critical coupling of the resonator to the 50 Ohms transmission line on a time scale that is short compared to the characteristic animal motion. During the short frequency scans, data collection is blocked by disabling the trigger signal to the digitizer (Keysight U1084A). The discrete auto-tuning mode permits signal detection of both in-phase and out-of-phase quadrature RF components. In comparison, the commonly used continuous AC AFC method may distort or entirely suppress the x-component of the transverse magnetization that is measured in the rotating frame associated with the excitation RF field. This may result in rapid-scan deconvolution algorithm failure. An additional advantage of DAFC is that a wide frequency scan (1–10MHz) can be used to find and lock on to the resonance frequency. In comparison, AC AFC range is often very limited. A detailed description of DAFC and its application for EPR imaging and spectroscopy, including experiments with conscious mice [41], will be submitted separately for peer-reviewed publication.

The second downconversion stage produces quadrature signals at the baseband. This is achieved by frequency mixing of the IF signal (after stage one) with an output of a second independent AWG channel that generates a CW IF reference (see Fig.1). This reference AWG signal can be offset with respect to IF by a fraction of the scan frequency to enable a near baseband detection method [42]. This method permits the use of a single detection channel to recover perfectly orthogonal quadrature RS EPR signals.

2.2.3. Surface loop resonator

A surface loop resonator was designed for RS EPR imaging of breast tumors in mouse models. The tumor size is often comparable to the resonator diameter, so that the breast tumors are placed inside the surface loop. As a result, both outer half-spaces divided by the loop plane contribute to the EPR signal. In this case, the resonator filling factor is maximized to improve EPR sensitivity and imaging volume. A previously reported L-band resonator [43] was modified to operate at 800 MHz. Several modifications were made to optimize the use of the CW resonator for RS EPR imaging as shown in Fig. 2. First, a pair of two parallel 50 Ohms coaxial cables (UT-047C-LL) were used to resonate the surface loop at the desired frequency. These cables are specified to have an outer diameter of 1.2 mm and the capacitance of C=86.8 pF/m. The total capacitance of two parallel soldered cables (connected in-series with respect to the coil inductance) is C/2 = 43.4 pF/m. The cables’ length, and therefore their capacitance, can be varied to fine-tune to the desired resonance frequency. The use of a small cable diameter reduces the amount of metal near the resonator loop, and therefore ensures a homogenous scanning magnetic field. Two 100 Ohms (UT-141–100-TP) coaxial cables were soldered together and used for impedance matching. Fine matching adjustments was achieved by a pair of varactors (Toshiba, 1SV239TPH3F). The lengths of the 100 Ohms coaxial cables were adjusted for the loaded resonator so that the varactors operate at high voltage end, where their capacitance is minimum. In this case, 200 Ohms output of the balun closely matches the 200 Ohms impedance of the coaxial cables to minimize impedance discontinuity. Instead of the traditional narrow-banded non-magnetic λ/2 coaxial balun, a broadband transformer (TP-103, Macom) was used. It operates in the range from 500 kHz to 1 GHz and the insertion loss of 0.4 dB is relatively low. The balun, coupler and first stage amplifiers were placed in a thick copper enclosure (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) to reduce noise and the periodic background signal that appears as the result of electric coupling between the resonator and the scan coils. The resonator and the scan coils are not the parts of a single mechanical structure and are well-separated in space. As a result, we have not observed any substantial background signal [44], even though no additional shielding was used.

The resonator loop and coaxial cables are supported by a 3D printed structure (Fig. 2 b, c, d). This structure was printed using a Formlabs 2 printer, which uses stereolithography (SLA) technology. The SLA method permits printing of solid water-impermeable structures with high resolution of 25–100 micrometers. This technology was used to embed a copper loop into a printed structure. The loop was inserted in a groove, covered with liquid resin and irradiated using a UV lamp to cause polymerization. Figure 2c shows the result of this procedure, which permits the use of an arbitrary thin wire in the design. A manual resonance frequency adjustment can be made by changing the distance between the loop and a bolt covered with a thin copper layer (see Fig. 2b). Bringing the conducting film closer to the loop decreases its effective inductance and therefore increases the resonance frequency. Inversely, moving the bolt away from the loop decreases the frequency.

2.2.4. Multi-frequency capabilities

The RF system (see Fig .1) can be used for experiments in a wide range of frequencies due to the implementation of the two-step downconversion. All parts of the system downstream of the first conversion to IF will remain unchanged and independent of the SF selection. In future studies, 250 MHz ± IF will be used to enable imaging of larger animals, and, potentially, humans. SF = 1000MHz will be used to RS-upgrade an existing clinical EPR system (CLIN EPR, Lyme NH). A resonator with supporting scan coils is being developed for PET/EPR co-imaging [35] that will operate in the range of 300 – 450 MHz.

2.3. Magnetic field unit

2.3.1. Magnet, gradients, and scan coils

A permanent magnet equipped with a set of 3D gradient coils was purchased from Ningbo Jansen NMR Technology LTD, Zhejiang, China. The magnetic field produced by the magnet is approximately 267 G, which corresponds to the EPR frequency of 750 MHz at g=2. A pair of Helmholtz coils (diameter 43 cm) were manufactured and mounted on the magnet poles to extend magnetic field range. Magnet wire OD=1.1 mm (MW0152, TEMCo CA) was used with total wire length of 200 m (total resistance 4 Ω). A Kepco ATE 25–20 M power supply is used that permits up to 40 G of field control range. This range can be increased by using a current source with a higher amperage output. In addition to the sweep coils a set of rapid scan coils were installed in the magnet (see Fig. 3). The supporting structures for the coils were 3D printed and embedded into the grooves that were cut in the garolite plates (brown horizontal plates in Fig. 3) using an available computer numerical control (CNC) machine. The coil has a Helmholtz configuration with a gap of approximately 10 cm. 120 turns of Litz wire (17 strands, OD =0.08 mm for each strand) were wound on each coil. Up to 14 G peak-to-peak scans were tested in the experiments without causing a significant coil heating.

It was found that the constant magnetic field produced by this permanent magnet is not homogeneous. Active shimming using linear gradients was performed to correct the inhomogeneities. The correction values were 5 mG/cm, 50 mG/cm, and −4 mG/cm for Gx, Gy, and Gz gradient components, respectively. Inhomogeneity over the imaging volume was less than approximately 2 mG/cm. Note that in four-dimensional images, field inhomogeneity causes line shift within a given voxel. This shift is corrected using EPR line fitting that includes line position as a parameter.

2.3.2. Gradient power amplifiers

Three pre-owned MRI amplifiers Copley-262 (denoted as A4 in Fig.1) were purchased that are specified to produce current amplitudes of up to 130 A. For the experiments presented here, a maximum of 20 A was used to generate a 3 G/cm gradient. This gradient is sufficient to achieve sub-millimeter resolution with trityl spin probes. The amplifiers are powered by a 10 kW DC power supply SGA330X30C0AAA (Ametek, CA). A NI PCIe 6363 DAQ card was used to generate control voltages for the gradient amplifiers and the Kepco ATE 25–20 M magnet power supply. Analog inputs of the card are used to monitor current produced by the Copley amplifiers and the constant magnetic field using a Hall probe (Teslometer FM 2002, Projelt Elektronik, Berlin).

2.3.3. Scan system and its digital automatic control

In RS EPR, the sinusoidal magnetic field scans across the entire spectrum twice every scan period. Transient rapid scan signals are measured. Deconvolution algorithms have been developed to transform RS signals into absorption spectra [25, 33]. The input parameters for the deconvolution algorithm are scan amplitude and phase. The algorithm assumes a sinusoidal function. Small uncertainties and/or instabilities of the scan amplitude, phase or deviation from the sinusoidal waveform would cause spectral distortions. Accurate calibration and stability of the magnetic scan parameters are critically important for RS EPR. This is especially the case for functional spectral-spatial imaging, where thousands of projections are often measured. Scan instability during data acquisition may skew functional parameters in the reconstructed images. To generate wide scans and ensure sinusoidal magnetic waveform, the scan coils are resonated with capacitors. As a result, a resonance circuit is formed that acts as a very efficient band pass filter. At the resonance frequency, the resonating capacitors compensate reactance of the coils, so that the total impedance of the circuit minimizes. This impedance approaches the direct current resistance of the wires. Losses in the coils’ environment cause an additional alternating current resistance that often increases with the scan frequency. A bank of switchable capacitors was used in RS EPR imaging experiments that permits the generation of six sinusoidal waveforms in the range from 9 to 100 kHz. At each frequency, accurate calibration of the coils, both amplitude and phase, was performed using a 1mM anoxic Finland trityl sample [45, 46]. The Finland trityl hyperfine splitting constants of 13C components were measured using an L-band EPR spectrometer (Magnettech, Germany, 1.2 MHz) and used as references for RS system calibration.

A RS coil driver design was previously reported by the Eaton lab. This driver controls the amplitude and phase of the scan waveform with high accuracy using an analog feedback loop [30, 47]. An alternative digital approach was implemented in our RS EPR imaging system. The function generator BK Precision 4052 is used to output a sinusoidal voltage waveform. The output of the generator is connected to the audio input of a Cerwin-Vega CV-1800 amplifier, shown as A3 in Fig.1. This amplifier is relatively inexpensive and can deliver up to 1.8 kW of power, which is sufficient for generation of a wide magnetic field scan. Heating of the coils becomes the major limiting factor. CV-1800 has a usable bandwidth up to 100 kHz. The amplifier does not operate in the current control mode and needs to be externally stabilized. Instead of analog, a digital feedback system was implemented. This system reads the voltage signal from a probe capacitor that is in-series with the coil. This signal is proportional to the amplitude and approximately 90° phase-shifted with respect to the current waveform. Voltage across the probe capacitor is digitized, and its amplitude and phase are computed by the dedicated background MATLAB program. Based on previous calibrations, amplitude and phase corrections are calculated and remotely sent to the function generator. The digital feedback system controls amplifier input to deliver the desired current waveform output. The amplifier gain can be varied manually without a need for recalibration. The feedback system will automatically adjust the amplifier input signal, its amplitude and phase. The use of the probe capacitor instead of a commonly used resister was found to be more advantageous. If the scan coils are resonated, voltage across the capacitor is relatively high compared to the noise levels even for very small scan amplitudes. In addition, the capacitor does not considerably reduce the quality factor of the resonated circuit compared to a resister. The fact that the current is out-ofphase with the respect to the voltage across the capacitor can be taken into consideration during calibration. A small remaining uncertainty (fraction of a degree) is corrected by the recently developed RS EPR deconvolution software [25]. A background MATLAB job, independent of the main program, continuously runs the digital feedback loop. When a scan amplitude change is required, the main program sends a command to the job and the new value is reliably established within approximately a second. The described above digital automatic scan control system (DASC) permits stable repeated measurements of very narrow lines (see Fig. 4), which could be a challenging task for some commercial EPR spectrometers. A low cost DASC system can be assembled with minimum effort.

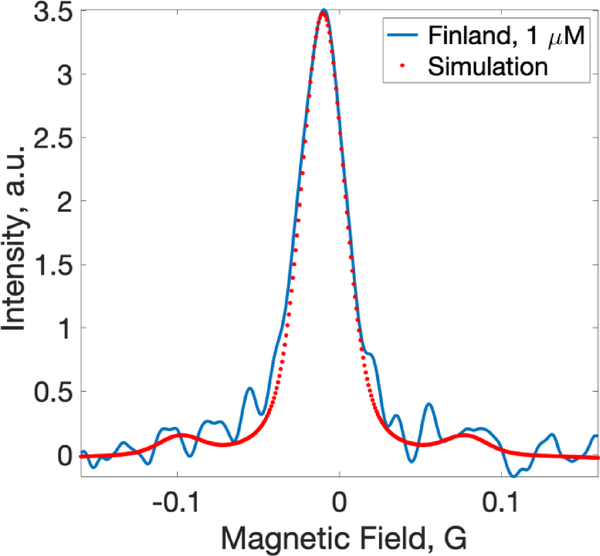

Fig. 4.

RS EPR spectrum of 1 μM de-oxygenated Finland radical (soild line) compared to a theoretical spectrum calculated using previously published spectroscopic data (dotted line). The spectrum was fitted using Easyspin with the inclusion of 13C hyperfine contributions.

2.4. Data Acquisition and Processing

Data acquisition control, rapid scan deconvolution, image reconstruction, and EPR line fitting are all done using MATLAB-based software. This software consists of the main program that has a user interface and two background job processes DAFC and DASC that run continuously independent of the main program. The jobs communicate with the main program through the file system by reading and writing short binary files within approximately 0.5 ms time. This type of communication was found to be faster when data are in binary format than by using a MATLAB memmapfile memory sharing function. Simultaneous writing to and reading from the same file may cause a conflict, which can be resolved by using the MATLAB try and catch function. For reconstruction of four-dimensional spectral-spatial images, 2546 spectra were measured, including 2520 projections and 26 zero- gradient EPR lines. These EPR spectra were measured after every 100 projections and used to software-compensate a drift of the external magnetic field. The drift of the external magnetic field is the result of warming of the permanent magnet due to the heat released by the gradient coils. During experiments, the magnetic field strength often slowly decreases. Periodic measurements of the EPR line position in the absence of the gradient field is used to measure and correct for the magnetic field change. Within a time interval between the zero-gradient measurements (6 – 12 seconds) the field drift is less than 1 mG. For four-dimensional image reconstruction, we used MATLAB code provided in the recent publication by Dr. Hirata’s group [48]. Line fitting of EPR spectra within the images were done using locally written MATLAB code that incorporated EasySpin (http://www.easyspin.org) routines.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Phantom

Deuterated Finland trityl radical was used as a spin probe for phantom imaging. This probe was synthesized according to published procedure [46]. A four-tube phantom was 3D-printed using the Formlabs Form2 printer. Each of the tubes had ID dimension of 3 mm in width and of 46 mm in length. The printed structure was water-impermeable and did not produce a measurable EPR signal in the range of interest. Trityl radical (1 mM) was dissolved in 100 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, an addition of glucose oxidase (Sigma, USA, 200 U/ml) and glucose (10 mM) was used to create anoxic conditions. A paramagnetic compound Gd-DTPA (BioPAL, Worcester MA USA) was added at concentration 0, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM to mimic oxygen-dependent linewidth broadening.

3.2. Probe preparation and calibration

Solutions of deuterated Finland (1 mM in 100 mM of Na-phosphate, pH 7.4) and OX71 trityl (in 150 mM of sodium chloride) probes were calibrated using two-point approach. The spectra of Finland and OX71 (also referred to as OX063d24) trityls were measured at two different oxygen conditions: (i) anoxic, created by an addition of glucose (10 mM) and glucose oxidase (200 U/ml) and (ii) at normal air (20.9 % or 159 mmHg of oxygen). Spectra were fitted with the voigtian EasySpin function. The Gaussian full width at half magnitude (FWHM) components were fixed and equal to 25 mG and 86 mG for Finland and OX71 EPR spectra, respectively. 13C hyperfine components were included in the fitting function. The slope of Lorentzian component linewidth dependence on oxygen partial pressure for the Finland radical was found to be approximately 1.2 mG/mmHg (FWHM), which corresponds to 0.7 mG/mmHg for peak-to-peak lineshape FWHM and peak-to-peak linewidth dependence for OX71 was measured to be 1.05 mG/mmHg and 0.60 mG/mmHg, respectively. Lorentzian FWMH contributions of the deoxygenated 1mM solutions were 54 mG and 26 mG for Finland and OX71 radical, respectively. Gaussian components (inhomogeneous broadening) are not affected by oxygen. The calibration parameters for both radicals are in good accordance with the previously published results [49, 50]. Multipoint calibration measurements will be repeated when pulsed capabilities of the system is fully developed. Direct measurements of the relaxation times will permit more accurate determination of the Gaussian contribution.

3.3. Experimental RS EPR parameters

All RS EPR measurements were done using 9400 kHz scan modulation frequency. The scan amplitude was varied depending on the width of EPR spectra and projections. In the imaging experiments, 2.5 G scan width was used for low-gradient projections and 6 G width for highgradient projections according to the following equation:

| (2) |

In Eq.3, N = 2546 was the number of projections that includes 26 zero-gradient spectra used to correct for the magnetic field drift, and FOV =1 cm is the field of view parameter.

The number of averages of periodic RS signals per projections was increased by a factor of four for the high-gradient projections to compensate reduction in signal-to-noise. A maximum gradient of 3G/cm was used in all imaging experiments. The RF power was selected that did not cause EPR line broadening due to the spin system saturation. Experimental data acquisition time for phantom and mouse imaging was 4 minutes (250 averages for 2.5 G scans) and 8 minutes (500 averages for 2.5 G scans), respectively.

3.4. EPR system sensitivity and stability

Evaluation of system sensitivity and stability were completed using de-oxygenated Finland trityl radical (1 μM) dissolved in the buffer solution that was prepared as described above. A tube (ID = 9 mm) containing the sample was placed in the resonator loop parallel to the loop’s axis. The tube’s length was greater than the sensitive area of the resonator. As a result, the sample filling factor was maximized. However, RF power distribution produced by the loop was very non-uniform throughout the sample volume. The deconvoluted absorption spectrum of the 1 μM Finland sample is shown in Fig. 4. This spectrum can be used as a reference for the evalaution of RS EPR system sensitivity. The total data acquisition time was 19 seconds. Signal-to-noise ratio (signal amplitude to SD of noise) was estimated to be approximately 20. Theoretical EPR spectrum was calculated for the purpose of comparison with the experimental EPR line. Easysipn voigtian function was used for this purpose. FWHM contributions were 25 mG and 12 mG for Gaussian and Lorentzian components, respectively. These parameters are based on the previously published data [50].

The performence of DASC was evaluated by repeated measurements of this sample, where the spectra were averaged to increase signal-to-noise ratios. No significant changes in the linewidth were observed. This experiment demonstrated the stability of both the scan amplitude and phase. Slow drift of the magnetic field during imaging experiments may cause apperant line broaderning if projections are avaraged for a long time. In practice, a single projection is measured during a short time period between 30 and 800 ms, depending on the imaging time.

3.5. Mouse model

All animal work was performed in accordance with the WVU IACUC approved protocol #1602000254. All experimental procedures were approved by West Virginia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female C57Bl/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Stock No: 000664) implanted with 1×106 PY8119 breast tumor cells (ATCC® CRL-3278™) were used in this study. The tumor cells were orthotopically implanted into the number 4 mammary gland. The mouse was placed into the holder and anesthetized by inhalation of air-isoflurane mixture using a DRE VP3 (DRE veterinary, USA) anesthetic machine. A tube with the gas mixture was connected to the rear side of mouse holder to provide continuous gas supply during the experiment. After the onset of anesthesia, a 50 μl of 2 mM of trityl OX71 radical (GE Healthcare) in isotonic NaCl solution was injected locally into the mouse breast tumor. The mouse was placed on its bed inside the magnet and the resonator was firmly placed on the tumor with the position of injection point in the geometric center of the resonator. Tumor volume was calculated using caliper measurements of length (L) and width (W) of tumor using the equation: V = [L × W2] × 0.5, where V is tumor volume [51].

4. Results

4.1. Phantom imaging

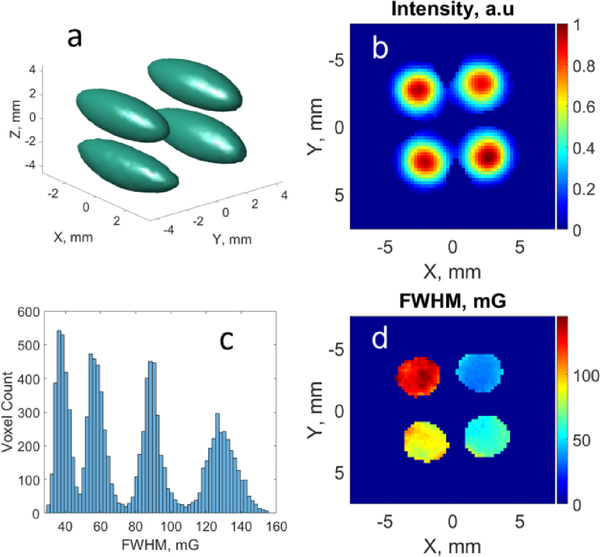

To evaluate the performance of the imaging system, a series of tests using various samples were conducted. Presented in Fig. 5 are the results of an imaging test done using a four-tube phantom. Deuterated Finland trityl radical at 1 mM concentration was used for the imaging experiments. Four solutions of the radical were prepared in 100 mM Naphosphate buffer, pH 7.4. An addition of glucose oxidase and glucose was used to create anoxic conditions for the length of EPR experiment. To each of the solutions an MRI contrast agent Gd-DTPA was added at the concentrations shown in Table 1. The role of gadolinium in the experiments was to mimic oxygen-dependent linewidth broadening in a controllable way. As a result, the observed broadening of the trityl EPR spectra (see Table 1) was exclusively due to the presence of gadolinium. 4D spectral-spatial images were measured and processed. The results are shown in Fig. 5c and Table 1 demonstrate good correlation of the imaging results with linewidth measurements of bulk solutions. In addition, there is a good correspondence between the image dimensions and phantom.

Fig. 5.

Phantom EPR imaging results. (a) 3D map of integral spectral intensity. The spheroid shape is the result of the inhomogenious RF field distribution that decays from the loop plane out; (b) 2D central slice of the integral intensity map; (c) Histogram showing linewidth distribution; (d) 2D central slice of the linewidth distribution.

Table 1.

Comparison of imaging and independent spectroscopic measurement results.

| Cylinder number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium concentration, mM | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 |

| FWHM Lorentz linewidth of the prepared solutions, mG | 40 | 64 | 87 | 122 |

| FWHM Lorentz linewidth mean and SD values in the image, mG | 42±6 | 61±7 | 90±8 | 127±10 |

4.2. In vivo imaging

The EPR imaging system described in this paper is currently used for oximetric imaging of a mouse model of breast cancer. Reporting of the cancer studies are beyond the scope of this paper. The goal of this paper is to provide a detailed technical description of the instrument, including in vivo demonstration. An example of an in vivo 4D image is shown in Fig. 6. An OX71 trityl spin probe (2 mM, 50 μL) was injected locally in mammary gland tumor. The size of the tumor (length × width) was approximately 10.8 × 10.3 mm, which corresponds to the volume of 573 mm3. The resonator (loop diameter = 13 mm) was placed on the tumor, so that part of the tumor was inside the resonating loop. An integral signal intensity-based threshold of 30 % was applied to the image. In vivo RS EPR capabilities of the described here system were demonstrated at 800 MHz for the first time.

Fig. 6.

EPR oximetric imaging of a mouse breast tumor. (a) Histrogram of pO2 distribution. (b) 2D slice of pO2 image.

5. Discussion

Table 1 permits estimation of functional oxygen resolution in images of about 5–8 mmHg depending on the linewidth. The accuracy of functional images can be further improved by enhancing system sensitivity and reducing reconstruction-related artefacts. Reduction of RF source noise contribution to images can be achieved through a bi-modal resonator design [32, 52]. In this design, two orthogonal resonators for excitation and detection are used. The excitation resonator acts as a bandpass filter that rejects source noise. The detection resonator measures the spin system response together with a strongly attenuated excitation signal. We are currently developing bi-modal resonators at 800 MHz for pre-clinical imaging and at 400 MHz the for PET/EPRI co-imaging project. The major challenge of this design is to achieve a stable inter-mode isolation when it is modulated by animal motion.

Besides sensitivity, improvements of image reconstruction methods and data processing are needed. This includes the selection of gradients that produce least correlated projections and the development of EPR line fitting algorithms that are less sensitive to image artefacts and noise but are more sensitive to the spectral parameters of interest. More advanced approaches, such as those based on neural networks, may help to improve the line fitting accuracy.

The RS EPR method permits measurement of one projection within the scan period, which is approximately 106 μs for 9400 kHz frequency used in the experiments. However, signal averaging is often required to improve signal-to-noise.

6. Conclusion and Future Plans

The EPR imaging system described in this paper was designed to conduct various types of standard EPR techniques and as a platform for the development of new experimental methods. Versatility and flexibility of the introduced design is achieved by the use of AWG that is frequency-mixed with low-noise RF sources. A future instrument upgrade will include pulsed EPR functionality. We will further develop field-modulated pulsed EPR methodology, which can be considered as a merging of pulsed and RS methods [37, 38]. The system will also be used to evaluate the advantages of RS EPR for clinical oximetry, including that at L-band. Toward this goal, the WVU Clinical & Translational Science Institute CW L-band spectrometer will be upgraded. The clinical EPR spectrometer was purchased from ClinEPR and operates at 1150 MHz. This frequency can be generated by mixing a 1000 MHz source and the AWG as described above.

The digital auto-frequency control method was developed that operates at the intermediate frequency, and therefore, will remain functionally independent on the frequency of operation. This method has a wide range of applications beyond in vivo imaging and may become an integral part of standard EPR spectrometers in the future.

Modular semi-digital EPR imaging system was developed

Digital automatic frequency control minimizes RF reflection

Digital automatic scan control stabilizes field scans

Surface loop resonator for RS EPR was developed

In vivo RS EPR imaging at 800 MHz was demonstrated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by NIH grants EB022775, EB023888, CA194013, CA192064, EB023990, R50CA211408, U54GM104942, and P20GM121322. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Matsumoto KI, Kishimoto S, Devasahayam N, Chandramouli GVR, Ogawa Y, Matsumoto S, Krishna MC, Subramanian S, EPR-based oximetric imaging: a combination of single point-based spatial encoding and T1 weighting, Magn Reson Med, 80 (2018) 2275–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kishimoto S, Matsumoto KI, Saito K, Enomoto A, Matsumoto S, Mitchell JB, Devasahayam N, Krishna MC, Pulsed Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Imaging: Applications in the Studies of Tumor Physiology, Antioxid Redox Signal, 28 (2018) 1378–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Elas M, Ichikawa K, Halpern HJ, Oxidative stress imaging in live animals with techniques based on electron paramagnetic resonance, Radiat Res, 177 (2012) 514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang X, Emoto M, Miyake Y, Itto K, Xu S, Fujii H, Hirata H, Arimoto H, Novel blood-brain barrier-permeable spin probe for in vivo electron paramagnetic resonance imaging, Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 26 (2016) 4947–4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Epel B, Sundramoorthy SV, Krzykawska-Serda M, Maggio MC, Tseytlin M, Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Rosen GM, J PYK, Halpern HJ, Imaging thiol redox status in murine tumors in vivo with rapid-scan electron paramagnetic resonance, J Magn Reson, 276 (2017) 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Elas M, Magwood JM, Butler B, Li C, Wardak R, DeVries R, Barth ED, Epel B, Rubinstein S, Pelizzari CA, Weichselbaum RR, Halpern HJ, EPR oxygen images predict tumor control by a 50% tumor control radiation dose, Cancer Res, 73 (2013) 5328–5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Emoto MC, Matsuoka Y, Yamada KI, Sato-Akaba H, Fujii HG, Non-invasive imaging of the levels and effects of glutathione on the redox status of mouse brain using electron paramagnetic resonance imaging, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 485 (2017) 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Koscielniak J, Devasahayam N, Moni M, Kuppusamy P, Yamada K, Mitchell J, Krishna M, Subramanian S, 300 MHz continuous wave electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer for small animal in vivo imaging, Review of scientific instruments, 71 (2000) 4273–4281. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hou H, Khan N, Kuppusamy P, Measurement of pO2 in a Pre-clinical Model of Rabbit Tumor Using OxyChip, a Paramagnetic Oxygen Sensor, Adv Exp Med Biol, 977 (2017) 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hou H, Khan N, Nagane M, Gohain S, Chen EY, Jarvis LA, Schaner PE, Williams BB, Flood AB, Swartz HM, Kuppusamy P, Skeletal Muscle Oxygenation Measured by EPR Oximetry Using a Highly Sensitive Polymer-Encapsulated Paramagnetic Sensor, Adv Exp Med Biol, 923 (2016) 351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Khan N, Hou H, Swartz HM, Kuppusamy P, Direct and Repeated Measurement of Heart and Brain Oxygenation Using In Vivo EPR Oximetry, Methods Enzymol, 564 (2015) 529–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Khan N, Hou H, Eskey CJ, Moodie K, Gohain S, Du G, Hodge S, Culp WC, Kuppusamy P, Swartz HM, Deep-tissue oxygen monitoring in the brain of rabbits for stroke research, Stroke, 46 (2015) e62–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bobko AA, Eubank TD, Driesschaert B, Dhimitruka I, Evans J, Mohammad R, Tchekneva EE, Dikov MM, Khramtsov VV, Interstitial Inorganic Phosphate as a Tumor Microenvironment Marker for Tumor Progression, Sci Rep, 7 (2017) 41233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Khramtsov VV, Bobko AA, Tseytlin M, Driesschaert B, Exchange Phenomena in the Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectra of the Nitroxyl and Trityl Radicals: Multifunctional Spectroscopy and Imaging of Local Chemical Microenvironment, Anal Chem, 89 (2017) 4758–4771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bobko AA, Eubank TD, Voorhees JL, Efimova OV, Kirilyuk IA, Petryakov S, Trofimiov DG, Marsh CB, Zweier JL, Grigor’ev IA, Samouilov A, Khramtsov VV, In vivo monitoring of pH, redox status, and glutathione using L-band EPR for assessment of therapeutic effectiveness in solid tumors, Magn Reson Med, 67 (2012) 1827–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kubota H, Komarov DA, Yasui H, Matsumoto S, Inanami O, Kirilyuk IA, Khramtsov VV, Hirata H, Feasibility of in vivo three-dimensional T 2(*) mapping using dicarboxy-PROXYL and CW-EPR-based single-point imaging, MAGMA, 30 (2017) 291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kmiec MM, Hou H, Lakshmi Kuppusamy M, Drews TM, Prabhat AM, Petryakov SV, Demidenko E, Schaner PE, Buckey JC, Blank A, Kuppusamy P, Transcutaneous oxygen measurement in humans using a paramagnetic skin adhesive film, Magn Reson Med, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jarvis LA, Williams BB, Schaner PE, Chen EY, Angeles CV, Hou H, Schreiber W, Wood VA, Flood AB, Swartz HM, Kuppusamy P, EPR Oximetry using OxyChip: Initial Results of Phase I Clinical Trial, in: Xth International Workshop on EPR in Biology and Medicine, Krakow, 2016, pp. 34. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jarvis LA, Williams BB, Schaner PE, Chen EY, Angeles CV, Hou H, Schreiber W, Wood VA, Flood AB, Swartz HM, Kuppusamy P, Phase 1 Clinical Trial of OxyChip, an Implantable Absolute pO(2) Sensor for Tumor Oximetry, International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics, 96 (2016) S109–S110. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Epel B, Bowman MK, Mailer C, Halpern HJ, Absolute oxygen R1e imaging in vivo with pulse electron paramagnetic resonance, Magn Reson Med, 72 (2014) 362–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Feintuch A, Alexandrowicz G, Tashma T, Boasson Y, Grayevsky A, Kaplan N, Three-dimensional pulsed ESR Fourier imaging, J Magn Reson, 142 (2000) 382–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Subramanian S, Koscielniak JW, Devasahayam N, Pursley RH, Pohida TJ, Krishna MC, A new strategy for fast radiofrequency CW EPR imaging: Direct detection with rapid scan and rotating gradients, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 186 (2007) 212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kittell AW, Camenisch TG, Ratke JJ, Sidabras JW, Hyde JS, Detection of undistorted continuous wave (CW) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra with non-adiabatic rapid sweep (NARS) of the magnetic field, J Magn Reson, 211 (2011) 228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Czechowski T, Chlewicki W, Baranowski M, Jurga K, Szczepanik P, Szulc P, Kedzia P, Szostak M, Malinowski P, Wosinski S, Prukala W, Jurga J, Two-dimensional spectral-spatial EPR imaging with the rapid scan and modulated magnetic field gradient, J Magn Reson, 243 (2014) 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tseytlin M, Full cycle rapid scan EPR deconvolution algorithm, J Magn Reson, 281 (2017) 272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Eaton SS, Quine RW, Tseitlin M, Mitchell DG, Rinard GA, Eaton GR, Rapid-Scan Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, in: Handbook of Multifrequency Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Data and Techniques, Wiley-VCH; Verlag, 2014, pp. 3–67. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Biller JR, Tseitlin M, Quine RQ, Rinard GA, Weismiller HA, Elajaili H, Rosen GM, Kao JPY, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Imaging of Nitroxides at 250 MHz using Rapid-Scan Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, J. Magn. Reson, 242 (2014) 162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tseitlin M, Yu Z, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Digitally generated excitation and near-baseband quadrature detection of rapid scan EPR signals, J Magn Reson, 249 (2014) 126–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mitchell DG, Tseitlin M, Quine RW, Meyer V, Newton ME, Schnegg A, George B, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, X-Band Rapid-scan EPR of Samples with Long Electron Relaxation Times: A Comparison of Continuous Wave, Pulse, and Rapid-scan EPR, Mol. Phys, 111 (2013) 2664–2673. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Quine RW, Mitchell DG, Tseitlin M, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, A resonated coil driver for rapid scan EPR, Concept Magn Reson B, 41B (2012) 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mitchell DG, Quine RW, Tseitlin M, Meyer V, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Comparison of Continuous Wave, Spin Echo, and Rapid Scan EPR of Irradiated Fused Quartz, Radiat Meas, 46 (2011) 993–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Buchanan LA, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Tabletop 700 MHz electron paramagnetic resonance imaging spectrometer, Concepts Magn Reson Part B Magn Reson Eng, 48B (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tseitlin M, Rinard GA, Quine RW, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Deconvolution of sinusoidal rapid EPR scans, J Magn Reson, 208 (2011) 279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mitchell DG, Quine RW, Tseitlin M, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, X-band rapid-scan EPR of nitroxyl radicals, J Magn Reson, 214 (2012) 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tseytlin M, Stolin AV, Guggilapu P, Bobko AA, Khramtsov VV, Tseytlin O, Raylman RR, A combined positron emission tomography (PET)-electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI) system: initial evaluation of a prototype scanner, Phys Med Biol, 63 (2018) 105010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sanzhaeva U, Xu X, Guggilapu P, Tseytlin M, Khramtsov VV, Driesschaert B, Imaging of Enzyme Activity by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Concept and Experiment Using a Paramagnetic Substrate of Alkaline Phosphatase, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 57 (2018) 11701–11705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tseytlin M, Concept of Phase Cycling in Pulsed Magnetic Resonance Using Sinusoidal Magnetic Field Modulation, Z Phys Chem, 231 (2017) 689–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tseytlin M, Epel B, Sundramoorthy S, Tipikin D, Halpern HJ, Decoupling of excitation and receive coils in pulsed magnetic resonance using sinusoidal magnetic field modulation, J Magn Reson, 272 (2016) 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tseitlin M, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Digital EPR with an arbitrary waveform generator and direct detection at the carrier frequency, J Magn Reson, 213 (2011) 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tseitlin M, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Reconstruction of the first-derivative EPR spectrum from multiple harmonics of the field-modulated continuous wave signal, J Magn Reson, 209 (2011) 277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tseytlin O, Bobko A, Tseytlin M, Anesthesia Free Pre-Clinical Rapid Scan Oximetry, in: 59th Annual Rocky Mountain Conference on Magnetic Resonance, Snowbird, Utah, 2018, pp. 87. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tseitlin M, Yu Z, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Digitally generated excitation and near-baseband quadrature detection of rapid scan EPR signals, J Magn Reson, 249C (2014) 126–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sugawara H, Hirata H, Petryakov S, Lesniewski P, Williams BB, Flood AB, Swartz HM, Design and evaluation of a 1.1-GHz surface coil resonator for electron paramagnetic resonance-based tooth dosimetry, IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, 61 (2014) 1894–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tseitlin M, Mitchell DG, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Corrections for sinusoidal background and non-orthogonality of signal channels in sinusoidal rapid magnetic field scans, J Magn Reson, 223 (2012) 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Song Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Villamena FA, Zweier JL, Characterization of the Binding of the Finland Trityl Radical with Bovine Serum Albumin, RSC Adv, 4 (2014) 47649–47656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Dhimitruka I, Grigorieva O, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV, Synthesis, structure and EPR characterization of deuterated derivatives of Finland trityl radical, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 20 (2010) 3946–3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Eaton GR, Tseitlin M, Quine RQ, Hall probe, epr coil driver and epr rapid scan deconvolution; Publication # WO 2014043513 A2; Application # PCT/US2013/059726, in, USA, 2014.

- [48].Komarov DA, Hirata H, Fast backprojection-based reconstruction of spectral-spatial EPR images from projections with the constant sweep of a magnetic field, J Magn Reson, 281 (2017) 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shi Y, Quine RW, Rinard GA, Buchanan L, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Epel B, Seagle SW, Halpern HJ, Triarylmethyl Radical OX063d24 Oximetry: Electron Spin Relaxation at 250 MHz and RF Frequency Dependence of Relaxation and Signal-to-Noise, Adv Exp Med Biol, 977 (2017) 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Laursen I, Leunbach I, Ehnholm G, Wistrand L-G, Petersson JS, Golman K, EPR and DNP properties of certain novel single electron contrast agents intended for oximetric imaging, J. Magn. Reson, 133 (1998) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Carbone DP, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I, Host A(2B) adenosine receptors promote carcinoma growth, Neoplasia, 10 (2008) 987–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rinard GA, Quine RW, Biller JR, Eaton GR, A Wire Crossed-Loop-Resonator for Rapid Scan EPR, Concepts Magn Reson Part B Magn Reson Eng, 37B (2010) 86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]