Abstract

Adolescent-era predictors of adult romantic life satisfaction were examined in a multi-method, prospective, longitudinal study of 165 adolescents followed from ages 13 to 30. Progress in key developmental tasks, including establishing positive expectations and capacity for assertiveness with peers at age 13, social competence at ages 15 and 16, and ability to form and maintain strong close friendships at ages 16 to 18, predicted romantic life satisfaction at ages 27 to 30. In contrast, several qualities linked to romantic experience during adolescence (i.e., sexual and dating experience, physical attractiveness) were unrelated to future satisfaction. Results suggest a central role of competence in non-romantic friendships as preparation for successful management of the future demands of adult romantic life.

The fundamental importance of a satisfying romantic life in adulthood is well established. The presence of functional romantic relationships has been linked to both adult mental health outcomes (e.g., lower levels of anxiety and depression (Horn, Xu, Beam, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2013; Wade & Pevalin, 2004)) as well as to greater short- and long-term physical health, and even to reduced risk of early mortality (Hughes & Waite, 2009). Although selection effects account for some of these findings, with healthier individuals more likely to have stable relationships, there is little question as to the centrality of romantic functioning to adult well-being (Horn, et al., 2013). This central role of romantic relationship functioning in adulthood suggests the importance of identifying its precursors at earlier stages of development.

Research to date has begun to identify factors in early- and mid-adolescence, such as family relationship quality, attachment experiences, and early peer competence that predict romantic relationship quality into late adolescence and the early twenties (Oudekerk, Allen, Hessel, & Molloy, 2015; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003; Simpson, Collins, & Salvatore, 2011). However, although identifying predictors into late adolescence and early adulthood is an important step, the implications of these predictions for longer-term romantic satisfaction are unclear given the developmental changes that continue to take place in romantic relationship functioning after the late adolescent and early adult period (Cohen, Kasen, Chen, Hartmark, & Gordon, 2003; Furman & Collibee, 2014). Although in outward form, adolescent and early adult romantic relationships may resemble relationships later in adulthood, substantial functional differences exist (Furman & Wehner, 1997). Given the need to gain experience with a variety of relationships prior to seeking a lifelong pair bond, adolescent and early adult romantic relationships are normatively and appropriately characterized by fluidity, moderate instability, and experimentation (Furman & Collibee, 2014; van Dulmen, Goncy, Haydon, & Collins, 2007). In contrast, later adult relationships more normatively focus on long-term stability and lifelong pair bonding, and indeed reflect a truly different stage of romantic development (Copen, Daniels, Vespa, & Mosher, 2012; Furman & Collibee, 2014). Sustaining satisfying long-term relationships in adulthood requires a combination of comfort with intimacy, competence in managing conflicts, and maturity to sustain commitments over long periods of time (Lawrence et al., 2008; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005; Patrick, Sells, Giordano, & Tollerud, 2007). This skill set differs significantly from the skill set needed during the adolescent and early adult period of exploration in romantic relationships (Shulman & Connolly, 2013). It thus remains an open question as to whether factors that predict adolescent or early adult relationship experiences will be the same as those that predict the longer-term romantic life satisfaction in adulthood. Indeed, virtually no research has examined this question.

A developmental tasks perspective (Waters & Sroufe, 1983) suggests that predictions of relationship satisfaction into late adolescence may well not generalize to later in adulthood. Even as late as the transition into adulthood (e.g., around age 20), romantic competence has not yet shown signs of displaying long-term stability (e.g., in terms of predictions to age 30 (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004)). Multiple scholars have argued, for example, that the traits necessary to do well in romantic relationships in late adolescence and early adulthood tend to not reflect core social developmental tasks at those stages, and thus may be less likely to predict longer-term relationship competence (Furman & Collibee, 2014; Roisman, et al., 2004). Adolescents, and even emerging adults, will care about and put effort into developing their romantic life, but romantic involvement is still normatively a hit-or-miss proposition. Indeed, for some adolescents, romantic involvement is even associated with more problematic functioning over time (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011; Szwedo, Chango, & Allen, 2015; Zimmer-Gembeck, Siebenbruner, & Collins, 2001).

From this perspective, establishing romantic relationships during adolescence is viewed as an emerging developmental task, but not yet as a salient developmental task, i.e., one that will reflect core competencies with long-term predictive implications (Roisman, et al., 2004). For example, the degree of involvement in romantic relationships in adolescence may be linked to social status during this period (Brown, 1999)—and even be a marker of such status—without necessarily predicting anything about long-term future relationship quality. Similarly, factors such as physical attractiveness or the amount of adolescent sexual experience may be central to the ways that adolescents and their peers perceive their romantic lives and their desirability as companions (Ha, Overbeek, & Engels, 2010; Vannatta, Gartstein, Zeller, & Noll, 2009). Yet, attractiveness is not a key capacity for adult romantic success and sexual experience can readily be gained at later ages, often with lower levels of risk (Mosher & Jones, 2010). Further, sexual experience within enduring, trusting relationships may be quite different from the types of experience often encountered in adolescent sexual relationships outside of a committed, stable relationship (Cohen, et al., 2003). Given that neither attractiveness nor experience is necessarily capturing progress in critical developmental tasks of adolescence, neither might be expected to predict long-term outcomes.

In contrast, a developmental tasks perspective (Raby, Roisman, Fraley, & Simpson, 2015; Roisman, et al., 2004; Sroufe & Jacobvitz, 1989) suggests that adult romantic life satisfaction will be best predicted by success managing the social developmental tasks that are both most salient within adolescence and that also bear the most functional resemblance to competencies that will be central to success in later adult romantic life (Furman & Collibee, 2014; Schulenberg, Bryant, & O’Malley, 2004). Crucially, this perspective suggests that these social developmental tasks will be predictive, even if they occur outside the context of adolescent romantic relationships. This developmental approach thus has the advantage both of suggesting factors that will be predictive of long-term adult romantic outcomes while also identifying factors that, although they may be relevant to adolescent-era romantic experience, would not be expected to necessarily predict longer term outcomes.

From this perspective, two key developmental tasks—establishing the ability to form close satisfying relationships and learning to maintain these relationships over time (Gottman, 2014; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005)—appear as both central to adolescent social development and likely to have implications for adult romantic life satisfaction. The ability and confidence to manage the give and take of close relationships so as to maintain them over time is clearly critical to maintaining satisfying romantic relationships in adulthood (Lawrence, et al., 2008; Patrick, et al., 2007). Yet, just as clearly, stability is not a term associated with most adolescent romantic relationships (Shulman & Connolly, 2013)—nor is it even clear that such stability would be adaptive at an age during which experimentation and exposure to multiple types of relationships may be most important (Furman & Wehner, 1997). There is one relationship context, however, where adolescents can readily develop and practice this critical capacity to establish and sustain close relationships: the domain of same-gender friendships. In contrast to often turbulent early- and mid-adolescent romantic relationships, in which stability is often atypical, non-romantic friendships provide a context in which establishing closeness and stability is a normative and feasible developmental task (Collins & Laursen, 2000). Even late adolescence is still largely a period of exploration in which long-term maintenance of a single romantic relationship, though it sometimes occurs, is not yet a primary developmental pattern (Arnett, 2000; Cohen, et al., 2003) (e.g., at age 18 a majority of adolescents aren’t even in a relationship at any given point in time (Rauer, Pettit, Lansford, Bates, & Dodge, 2013) and from 16 to 24 a majority of youths have not yet begun to display a pattern of engaging in longer-term relationships (Boisvert & Poulin, 2016)). Non-romantic close friendships, in contrast, are almost ideal contexts for developing capacities for closeness and stability in relationships, although no research has examined links between such friendship qualities and long-term romantic outcomes (i.e., extending beyond the late adolescent, early twenties transition). Roisman and colleagues (2004) did, however, find that by the time of the transition to adulthood, around age 20, broad peer competence was a better predictor of romantic competence at age 30 than was romantic competence at 20. Research has not, however, examined whether these types of continuities exist from adolescence onward, nor which aspects of adolescent peer relationships will be most likely to predict longer-term romantic satisfaction.

As with most developmental tasks, developing the capacity to form close, stable, adult-like relationships typically proceeds in gradual stages (Bukowski, Motzoi, & Meyer, 2009). Early in adolescence, friendships are transitioning from a basis in common activities (as in childhood) toward adult-like relationships based upon intimacy and mutual perspective-taking (Lawrence, et al., 2008; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005). During this early period, stability may not yet be present, but the developmental foundations of later stable friendships are being put into place. Attachment and autonomy processes have been heavily implicated as key elements in these foundations during this period (Chango, Allen, Szwedo, & Schad, 2015). In terms of attachment processes, security is characterized by positive expectations of others in relation to the self. A key task thus appears to be for adolescents to develop an overall positive stance toward and expectations of peers as potential friends (Allen & Miga, 2010; Allen & Tan, 2016). Indeed, establishing such secure expectations has been found to predict both competence with friends in adolescence and with romantic partners into the early twenties (Loeb, Tan, Hessel, & Allen, 2016; Simpson, Collins, Tran, & Haydon, 2007), although it has never been examined in relation to longer-term romantic outcomes.

Similarly, the capacity to establish autonomy in interactions with peers by asserting oneself in the face of disagreements in close relationships is steadily developing across adolescence and has been linked to long-term social competence (Oudekerk, et al., 2015). Unlike efforts to establish romantic relationships, the effort to learn to manage autonomy and assertion challenges is a core, stage-salient task in early and mid-adolescence, and is particularly relevant in contexts where adolescents are learning to manage peer pressure and peer influence (Chango, et al., 2015). Notably, the capacity to establish autonomy successfully is also a widely-recognized quality of successful adult romantic relationships and has been linked to quality, support and long-term stability of romantic relationships in adulthood (Askari, Noah, Hassan, & Baba, 2012; Hinnen, Hagedoorn, Ranchor, & Sanderman, 2008; Ménard & Offman, 2009). Establishing fundamental relational competencies in early adolescence, such as positive expectations of relationships and ability to manage autonomy challenges, would in turn be expected to predict the development of confidence about one’s actual competence in ongoing relationships with peers by mid-adolescence. This confidence in one’s social competence is likely in turn to lead in late adolescence to the capacity to both form and maintain truly close friendships. Prior research has posited, though not yet empirically tested, the premise that broad peer competence at this age is likely to be a link in a chain that ultimately leads to long-term romantic competence (Raby, et al., 2015).

In considering predictors of romantic outcomes, gender differences in specific romantic qualities such as intimacy, attachment, and relationship satisfaction have all been identified (Del Giudice, 2011; Hendrick & Hendrick, 2006; Zimmer-Gembeck & Petherick, 2006). At the same time, considerable uncertainty exists as to whether gender differences exist in the importance of any of a variety of adult romantic relationship qualities (e.g., marital status, relationship quality, etc.) (Simon, 2002; Strohschein, McDonough, Monette, & Shao, 2005; Williams, Connolly, & Segal, 2001). Given these uncertainties, the consideration of gender as a potential moderator in romantic relationship research has been suggested as a routine practice (Bouchey, 2007). Also, in assessing adult romantic experience, it should be noted that even well into adulthood, many competent individuals have not necessarily identified an ideal long-term partner, even though they may be progressing well in terms of key tasks needed to establish a successful romantic life, and indeed experiencing romantic life as successful (Rauer, et al., 2013). Thus, even at this stage, we focus not on the presence of a specific relationship, but rather on the individual’s assessment of the quality of their overall romantic life. This perception of overall romantic life satisfaction is particularly useful at this stage, as it can be assessed independently from the presence vs. absence of a current relationship, and it has long been recognized to be linked to both overall mental and physical health (Traupmann & Hatfield, 1981) as well as to specific biomarkers linked to physical health and aging processes (e.g., lower levels of interleukin-6 (Allen, Loeb, Tan, & Narr, 2017)).

To identify factors in adolescence that predict romantic relationship satisfaction beyond the late adolescent to early adult transition, this prospective, multi-method study followed a diverse community sample from age 13 to ages 27 to 30. Specifically, the study examined the hypotheses that adult romantic life satisfaction will best be predicted:

-

1

In early adolescence, by positive expectations of peer relationships and appropriate assertiveness with peers.

-

2

In mid-adolescence, by social competence with peers.

-

3

In late-adolescence, by ability to establish close and stable friendships.

In addition, the study examined the hypotheses that:

-

4

Effects of earlier predictors will be mediated via later markers of relationship competence.

-

5

Factors likely to be cross-sectionally associated with romantic relationship experience within adolescence (e.g., physical attractiveness, number of partners, etc.) are less likely to be predictive of long-term outcomes.

Potential moderation by participant gender was considered for all hypotheses.

Methods

Participants & Statistical Power

This report is drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation of adolescent peer influences on adult development. The final sample of 165 participants was a subsample (selected based on availability of romantic life satisfaction data at ages 27 to 30) from an original sample of 184 participants initially assessed at age 13 (an 89% retention rate across 17 years). The final sample included 71 males and 94 females and was racially and ethnically and socioeconomically diverse and representative of the community from which it was drawn: 94 adolescents (57%) identified themselves as Caucasian, 49 (30%) as African American, 1 (<1%) as Hispanic, 2 (1%) as Asian, 1 (<1%) as American Indian, and 18 (11%) as of mixed race or ethnicity. As adults, 150 participants identified themselves as heterosexual (90%), 2 (1%) as gay males; 4 (2%) as lesbian females, 7 (4%) as bisexual, and 2 (1%) as other. Adolescents’ parents reported a median family income in the $40,000 - $59,999 range at the initial assessment.

Adolescents were recruited from the 7th and 8th grades of a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States. Information about the study was provided via an initial mailing to parents with follow-up presentations to students at school lunches. Formal recruitment took place via telephone contact with parents. Students who had already served as close peer informants in the study were not eligible to serve as primary participants. Of students eligible for participation, 63% of adolescents and parents agreed to participate when parents were contacted. Adolescents provided informed assent before each interview session, and parents and adult participants provided informed consent. Interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building.

Assessments in this study were obtained at mean ages 13.3 (SD = .64), 15.2 (SD = .83), 16.3 (SD = .88), 17.3 (SD = .87), 18.3 (SD = 1.1), 27.6 (SD = .99), 28.6 (SD = 1.00), and 30.0 (SD = .89). At the age 16 through 18 assessments, participants also nominated their closest friend who was not a romantic partner to be included in the study (not necessarily the same friend across ages). Close friends participated with informed assent or consent, and parental consent if they were minors. Where the closest friend was not available or willing to participate, the next closest friend was selected; close friend data were available for 156 of the 165 participants in the study (attrition analyses are described below). Close friends reported that they had known the adolescents for an average of 5.7 years (SD =3.8) at the age 16 assessment, 5.9 years (SD= 4.0) at the age 17 assessment, and 6.9 years (SD = 4.5) at the age 18 assessment. They were also close in age to target participants (Ages 16.0 (SD =1.1); 16.9 (SD =1.3); 18.5 (SD =1.9) respectively, at the age 16, 17, and 18 participant assessments) and overwhelmingly of the same gender as the target participant (99% at age 16, 96% at age 17 and 93% at age 18). Adolescents who were in a sustained romantic relationship (e.g., lasting 3 months or longer) between ages 17 and 19 (N = 97) were also asked to complete questionnaires about their satisfaction in that relationship.

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses examined missing data for each variable available at baseline. Females were more likely than males to have continued the study into the adulthood assessment period (96% continuation rate for females vs. 83% for males, p = .003). Other than this one difference, there were no attrition effects on any of the adolescent-era assessments described below for any baseline or mediating measures, suggesting that attrition was not likely to have distorted the findings reported. Among those individuals who continued into the adult assessment, females were slightly less likely to have close friend data available (8.5% missing for females vs. 1.4% for males, p =.046), but otherwise there were no effects of close friend missing data. When comparing individuals who did vs. did not have data on a current romantic relationship at ages 17 to 19, those not in a relationship who had already become sexually active reported becoming active at a slightly earlier age (14.6 years vs. 15.3 years, p = .02) but did not differ on any other measures, including on the likelihood of having become sexually active by this assessment point. To best address any potential biases due to attrition in longitudinal analyses or missing data within waves, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods were used with analyses including all variables that were linked to future missing data (i.e., where data were not missing completely at random). Because these procedures have been found to yield the least biased estimates when all available data are used for longitudinal analyses (vs. listwise deletion of missing data) (Arbuckle, 1996), the entire original sample was utilized for these analyses. This full sample thus provides the best possible estimates of variances and covariances in measures of interest and was least likely to be biased by missing data.

Procedure

In the initial introduction and throughout all sessions, confidentiality was assured to all study participants and adolescents and adults were told that no one would be informed of any of the answers they provided. Participants’ data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which protected information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. Transportation and childcare were provided if necessary. Adolescent and adult participants and participants’ peer reporters were all paid for participation.

Measures

Positive Expectations of Peers (Age 13).

Adolescents’ expectations of peers were assessed at age 13 using the Children’s Expectations of Social Behavior Questionnaire (Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1995). This measure consists of 15 hypothetical vignettes in which teens are asked to imagine themselves interacting with their peers around a variety of moderately stressful situations (e.g., being upset and wanting to talk to a friend; looking awkward playing a sport in front of peers). Teens were then asked to select their peers’ most likely type of response if these situations occurred, with peers’ expected responses ranging from hostile to neutral to supportive, scored on a 0 – 2 scale. Scores were then summed, with higher scores representing teens’ more positive expectations of peers’ behavior towards them. The scale had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.75).

Assertiveness (Age 13).

A modified version of the Adolescent Problem Inventory (Freedman, Rosenthal, Donahoe, Schlundt, & McFall, 1978) was used to assess adolescents’ assertiveness by examining how effectively participants were able to respond to peers’ attempts to encourage deviant behavior. In this analogue-test measure, adolescents provided their most likely responses to a series of hypothetical vignettes in which peers encouraged deviant behavior (e.g., shoplifting, skipping school, etc.). Adolescent responses were audio-recorded and then rated by coders unfamiliar with other data from the study on a 0 to 10 scale in terms of competence and assertiveness of the response. Interrater reliability, calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient, was in what has been labelled the “excellent” range for this statistic (ICC =.87) (Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981).

Social Competence (Ages 15 and 16).

The 4-item social competence scale from the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988) was used to assess the target teen’s perception of their overall competence in forming and maintaining friendships with peers. The measure was collected at both the age 15 and age 16 assessments with results averaged to produce the final scale. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α =.76 at 15; .86 at 16) and the correlation across ages was strong (r = .69, p < .001).

Peer-rated Friendship Closeness (Ages 17 and 18).

Participants’ closest peer was asked at each of ages 17 and 18 to rate the overall closeness of the friendship on a scale ranging from 1 – Not Very Close to 5 – Best Friend. Ratings were moderately correlated ((r = .23, p = .01) even though they were often from different friends rating different friendships) and were averaged across the two ages.

Close Friendship Stability (Age 16 to Age 18).

This dichotomous behavioral variable denoted whether or not participants had the same peer actually participate in the study as their closest peer across this two-year span from age 16 to age 18 and is correlated with close-friend-rated closeness in the following year (r = .22, p < .05).

Romantic Relationship Satisfaction (Ages 27, 28, & 30).

Participants reported their degree of overall relationship satisfaction on the Likert-style, 5-item Romantic Relationship Satisfaction scale of the Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction Measure (Hare & Miga, 2009) which has been previously (inversely) linked to levels of Interleukin-6 in the bloodstream (a marker of stress response) (Allen, et al., 2017) and to the reported duration of the longest relationship during this period. The measure asks participants to address satisfaction and distress (reverse-coded) with their current romantic life using items such as, “I am very satisfied with my current romantic life” and “I spend a lot of time worrying about my current romantic life” (reverse-coded). The measure displays good internal consistency across the years of this study (Cronbach’s α = .88 to 89) and substantial two-year stability from age 28 to age 30 (r = .54, p < .001). Ratings were summed and averaged across ages 27, 28, and 30 to yield the final scale for this measure.

Romantic Relationship Satisfaction (Ages 17–19).

Adolescents completed the 7-item relationship satisfaction scale from the Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, Dicke, & Hendrick, 1998) as a measure of their satisfaction in a current romantic relationship of at least 2 months duration. Internal consistency was good (α=.82).

Romantic Appeal (Ages 15 and 16).

The romantic appeal scale from the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988) was used to assess the target teen’s perception of their appeal as a potential romantic partner. The measure was collected at both the age 15 and age 16 assessments with results averaged to produce the final scale. Internal consistency for this 4-item measure was good (Cronbach’s α =.70 at 15; .75 at 16) and the correlation across ages was strong (r = .57, p < .001).

Dating experience –

At age 17, participants reported on their dating and romantic experience to that point, including number of boy or girlfriends, and romantic physical involvement operationalized as the number of romantic partners with which participants reported having ‘made out.’

Sexual experience –

At age 17, participants reported both on whether they had yet had consensual sexual intercourse, and if so, the age at which they first had consensual intercourse. Presence vs. absence of intercourse experience was coded, along with age at first sex.

Physical attractiveness (Ages 13, 17).

Target participants’ physical attractiveness was coded from the first 10 seconds of (audio muted) video-recorded observations of the target engaged in social interactions at age 13 and again at 17. Half of the video display was covered, so as to show only the target participant, and audio was muted. Physical attractiveness was coded using a naïve rater strategy (Kopera, Maier, & Johnson, 1971; Patzer, 1985), in which coders apply their lay understanding of the meaning of a given construct or term, in this case ‘physical attractiveness’. The coding team (n = 8) included both males and females and was ethnically diverse. Naïve coding systems attain reliability by compositing ratings from multiple raters, and in this case yielded highly reliable ratings at ages 13 (ICC = .85), and 17 (ICC = .87).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Means and standard deviations for all substantive variables examined are presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations are presented in Table 2. Participants’ sexual orientation (coded as heterosexual vs. other for analyses) was unrelated to romantic life satisfaction (p > .20). Given the small number of non-heterosexual participants, analyses of moderation with this variable were not feasible.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of All Variables Examined

| Primary Outcome & Hypothesized Predictors | Mean | SD |

| Romantic Life Satisfaction (Ages 27–30) | 15.7 | 3.05 |

| Assertiveness (Age 13) | 22.8 | 7.30 |

| Positive Expectations of Peers (Age 13) | 3.36 | 3.72 |

| Social Competence Peer (Age 15–16) | 39.0 | 5.62 |

| Friend-reported Friendship Closeness (Age 17–18) | 4.38 | 0.83 |

| Observed Close Friend Stability (Age 16–18) | 34% | |

| Other Measured Variables | ||

| Perceived Romantic Appeal (Age 15–16) | 12.0 | 2.65 |

| Prior number of boyfriend or girlfriends (Age 17) | 7.43 | 17.4 |

| Physical Romantic Involvement (Age 17) | 3.18 | 1.45 |

| Prior Sexual Intercourse (Age 17) | 61% | |

| Physical Attractiveness (Age 13) | 3.68 | 0.76 |

| Physical Attractiveness (Age 17) | 3.63 | 1.09 |

| Romantic Relationship Satisfaction (Age 17–19) | 31.0 | 3.53 |

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Primary Study Variables

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Romantic Life Satisfaction (Age 27–30) | .26*** | .22** | .24** | .25** | .29** | .23** | −.01 | −.09 | .05 | .11 | .06 | .07 | .05 | .00 |

| 2. Assertiveness (Age 13) | −.18* | .00 | .07 | .14 | −.03 | −.00 | −.20* | −.01 | −.13 | −.12 | .02 | .21** | −.07 | |

| 3. Positive Expectations of Peers (Age 13) | −.22** | −.19* | .02 | −.10 | .09 | .02 | .08 | −.09 | −.07 | −.00 | −.22** | −.20** | ||

| 4. Social Competence Peer (Age 15–16) | .26*** | .06 | .74*** | −.07 | .13 | .02 | .05 | .01 | .07 | .10 | −.05 | |||

| 5. Friendship Closeness (Age 17–18) | .14 | .17* | .07 | −.03 | −.13 | .10 | .05 | .00 | .05 | .03 | ||||

| 6. Close Friend Stability (Age 16–18) | .13 | −.08 | .05 | .00 | −.01 | .00 | .26* | −.11 | .21* | |||||

| 7. Romantic Appeal (Age 15–16) | −.04 | .21** | .18 | .09 | .09 | .06 | .03 | −.14 | ||||||

| 8. Number of boy or girlfriends (Age 17) | .26** | .16 | .16* | .12 | −.26** | −.18* | −.07 | |||||||

| 9. Physical Romantic Involvement (Age 17) | .42*** | .34*** | .29*** | −.16 | −.30*** | .14 | ||||||||

| 10. Prior Sexual Intercourse (Age 17) | .08 | .03 | .03 | −.14 | −.21 | |||||||||

| 11. Physical Attractiveness (Age 13) | .56*** | −.11 | −.17* | .12 | ||||||||||

| 12. Physical Attractiveness (Age 17) | −.00 | −.08 | .17* | |||||||||||

| 13. Romantic Relationship Satisfaction (Age 17–19) | .07 | .14 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Gender (1= M; 2= F) | −.11 | |||||||||||||

| 15. Family Income (Age 13) |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Gender and baseline family income were included as covariates and potential moderators in all analyses. Moderating effects were assessed by creating interaction terms based on the product of the centered main effect variables. A moderating effect of gender and stability of close friendship in late adolescence predicting adult relationship satisfaction was observed and is described below. No other moderating effects of gender or family income were detected.

Primary analyses

Hypothesis 1: Adult romantic life satisfaction will be predicted by early adolescent positive expectations of peer relationships and appropriate assertiveness.

For all primary analyses, SAS PROC CALIS, version 9.4 (Sas Institute, 2015) was employed using full information maximum likelihood handling of missing data for assessment of key relations in hierarchical regression models. Analyses first examined predictions of adult romantic life satisfaction from two early adolescent developmental tasks: holding positive expectations of peer relationships and establishing appropriate assertiveness in the face of peer influence attempts. Models also accounted for adolescent gender and baseline income in adolescents’ family of origin. Results, presented in Table 3, indicate that both the test measure of assertiveness and adolescents’ reports of positive expectations of peer relationships each added unique variance to the prediction of future romantic satisfaction. Together these early adolescent predictors accounted for 9.9% of the observed variation in adult levels of romantic life satisfaction after accounting for baseline demographic covariates.

Table 3.

Predicting Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction from Early-Adolescent Peer Relationship Qualities

| Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction (Age 27–30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | |||

| Gender (1-M; 2=F) | −.04 | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | −.02 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .003 | .003 | |

| Step II. | |||

| Assertiveness (Age 13) | .24** | ||

| Positive Expectations of Peers (Age 13) | .19** | ||

| Statistics for Step | .099*** | .102*** | |

p < .001.

p ≤ .01.

p < .05.

β’s are from final model.

Hypothesis 2: Adult romantic life satisfaction will be predicted by mid-adolescent social competence with peers.

Using the same analytic approach described above, results presented in Table 4 indicate that social competence with peers in mid-adolescence (ages 15–16) also predicted adult romantic life satisfaction accounting for 5.4% of the variance over and above baseline demographic variables.

Table 4.

Predicting Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction from Mid-Adolescent Peer Relationship Qualities

| Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction (Age 27–30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | |||

| Gender (1-M; 2=F) | −.04 | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | −.02 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .003 | .003 | |

| Step II. | |||

| Social Competence (Ages 15–16) | .23** | ||

| Statistics for Step | .054** | .057** | |

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

β’s are from final model.

Hypothesis 3. Adult romantic life satisfaction will be predicted by ability to establish close and stable late-adolescent close friendships

As noted above, preliminary analyses revealed a moderating effect of gender on friendship stability in predicting later romantic satisfaction. Using the analytic approach described above, results presented in Table 5 indicate that the combination of the main effect of observed friendship stability, its interaction with gender, and the main effect of friendship closeness as reported by a best friend accounted for 18.8% of the variance in romantic satisfaction over and above demographic variables. Follow-up analyses conducted separately by gender, also shown in Table 5, revealed a strong relationship for friendship stability for males as a predictor of future romantic life satisfaction, but a non-significant relationship of friendship stability predicting romantic life satisfaction for females.

Table 5.

Predicting Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction from Late-Adolescent Peer Relationship Qualities

| Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction (Age 27–30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | |||

| Gender (1-M; 2=F) | .08 | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | −.04 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .003 | .003 | |

| Step II. | |||

| Peer-reported Friendship Closeness (Ages 17–18) | .24** | ||

| Friendship Stability (Ages 16–18) | .26** | ||

| Friendship Stability × Gender (β Males: .45*** β Females: .07) | −.23** | ||

| Statistics for Step | .188*** | .191*** | |

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

β’s are from final model.

Hypothesis 4. Effects of earlier predictors will be mediated via later markers of relationship competence.

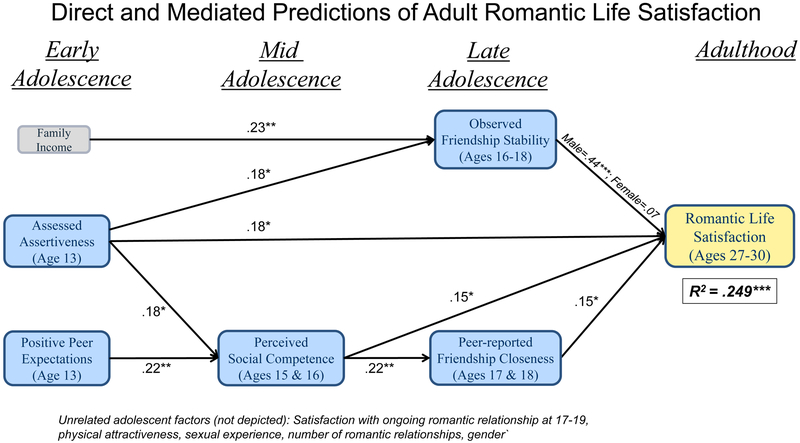

Figure 1 presents the results of a path model examining the conjoint and mediated predictions of adult romantic life satisfaction. The model was constructed by first assessing all earlier variables as potentially predicting all later variables, and then deleting non-significant paths. The resulting model fit the data well (GFI = .98, AGFI = .94, RMSEA = 0.0, χ2 (13) = 9.56, p = .73) and accounted for 24.9% of the variance in adult romantic satisfaction at ages 27 to 30. Early adolescent assertiveness, social competence at age 15 and 16, and friendship closeness at ages 17 and 18 were all directly and uniquely predictive of future romantic satisfaction. Close friendship stability from ages 16 to 18 was also directly and uniquely predictive of future romantic satisfaction, though only for males. Positive expectations of peers at age 13 were indirectly related to future romantic satisfaction, via a relation to social competence at age 15 and 16, which in turn was predictive of friendship closeness at age 17 and 18 (Indirect β = −.06, p = .02). Participant gender had no significant direct relationships with other variables in the model and, for model clarity, is not depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 –

Direct and Mediated Predictions of Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction

Hypothesis 5. Adolescent romantic experiences and qualities that are unrelated to core developmental tasks will not be significantly predictive of adult relationship satisfaction.

We examined a number of factors that did not reflect central developmental tasks of adolescence, and yet are relevant to romantic relationship experience in adolescence, as predictors of adult romantic satisfaction. Among these were participants’ ratings of their own romantic appeal across ages 15 and 16, total number of romantic relationships experienced by age 18, physical romantic involvement prior to 18, whether or not the participant had had sexual intercourse prior to age 18, adolescents’ reported satisfaction in an ongoing romantic relationship between the ages of 17 and 19, and observer ratings of participants’ physical attractiveness at ages 13 and 17. On a post-hoc basis, we also examined participant’s age at first consensual sex as both as a linear and quadratic effect, and neither was found to predict future relationship satisfaction.

Only participant perceptions of romantic appeal were significantly linked to long-term romantic life satisfaction in zero-order correlations (r = .23, p = .003). Follow-up analyses considered whether inclusion of romantic appeal in the overall model above would significantly alter observed paths from other factors to later satisfaction. When added to this model, romantic appeal was marginally related to later satisfaction (β = .14, p = .054). The only change to the model was that perceived social competence (assessed at the same age and as part of the same overall measure as romantic appeal) became non-significant, which appeared a result at least in part of the high degree of shared variance between the two constructs (r = .74, p < .001).

Discussion

This study extends our understanding of the key developmental tasks involved in establishing the capacity to achieve long-term romantic life satisfaction. Using a combination of analogue-test, behavioral, peer-, and self-report measures, this study identified a number of adolescent-era predictors of romantic life satisfaction well into adulthood (ages 27–30). The identified predictors were consistent with a developmental tasks perspective, in which establishing the ability to form and maintain strong non-romantic relationships in adolescence was a precursor to satisfaction with romantic life in adulthood. Notably, observed continuities were primarily heterotypic, not homotypic: Factors that were associated with romantic behavior in adolescence, but not necessarily reflective of progress in core developmental tasks, were generally not predictive of later romantic satisfaction. In contrast, and consistent with prior research and theory, evidence of progress in key social developmental tasks in adolescence was predictive of future romantic competence, even though the tasks of adolescence were in non-romantic domains (Raby, et al., 2015; Roisman, et al., 2004). Each of these findings is discussed in detail below, along with consideration of their limits.

Results were consistent with a focus on the core developmental tasks at each stage of adolescence observed. The findings reflect the steady development across adolescence of the capacities needed to establish and sustain adult-like intimate relationships. Early in adolescence, we see this capacity emerging in nascent form. During this stage, predictors of later romantic competence revolved around two core peer competencies: the ability to be appropriately assertive with peers and establishing positive expectations of peer interactions. These predictions are consistent with theories suggesting that in this early ‘initiation’ phase of adolescent romantic development, self-concept related competencies (rather than overt romantic behaviors) may be most central (Brown, 1999; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). Hence, what is most developmentally relevant appears to be the presence of underlying capacities—in terms of positive expectations and competence in managing autonomy challenges with appropriate assertiveness—that are readily achievable at this early stage and which can serve as the basis for future competence in more intense relationships.

More specifically, adolescents’ confident expectations of peers’ likely positive responses to them in a variety of situations were directly predictive of later romantic satisfaction in initial models examined, and indirectly predictive in final models, with the relation to future satisfaction mediated via later perceived social competence and peer-reported friendship closeness. Establishing such confident expectations may well happen prior to adolescence, of course, and likely has attachment roots (Collins & van Dulmen, 2006; Zimmermann, 2004). Nonetheless, given the increase in intensity of relationships that comes with adolescence, this may be a particularly important period during which to establish positive expectations of peers.

Similarly, an early adolescent capacity for assertiveness in the face of pressure from peers, assessed via an analogue-test procedure, displayed both a direct relationship to future romantic relationship satisfaction as well as a relationship mediated via friendship stability later in adolescence. These findings are consistent with a longstanding body of research on the importance of autonomy and assertiveness processes, both in adolescent parent and peer relationships, as well as in adult romantic relationships (Hui, Molden, & Finkel, 2013; Oudekerk, et al., 2015). The finding that in final multivariate models, assertiveness continued to uniquely predict significant variance in adult romantic satisfaction even after accounting for later variables is consistent with the notion that this capacity, even as displayed early in adolescence, may be central to relationship functioning across a significant portion of the lifespan (Ryan, Deci, & Grolnick, 1995).

In mid-adolescence, overall social competence—operationalized in terms of the adolescents’ ability to establish close friendships and manage broad peer relationships—was predictive, consistent with theoretical perspectives on the key developmental tasks of this phase (Brown, 1999). Late in adolescence, actual abilities to establish and maintain close friendships predicted future romantic competence and partially mediated predictions from qualities assessed earlier in adolescence. By late adolescence, the observed predictors of future romantic life satisfaction were those which more directly translate to the actual competencies required to establish close and relatively stable romantic relationships in adulthood. The key markers of future competence observed at ages 16 to 18 appeared to be high ratings of closeness by selected friends and the formation of friendships that were stable across a two-year period (though only for males). Closeness and stability were not intercorrelated, suggesting that they may reflect different components of social competence (i.e., some very close friendships may not be all that stable, and vice versa). In brief, these findings suggest that the best predictors of romantic satisfaction in adulthood may be the ability to establish strong, stable close friendships in late adolescence. The finding of gender moderation in predictions from friendship stability to romantic satisfaction is consistent with research suggesting that male adolescents are potentially somewhat behind female adolescents in capacity to establish intimate relationships (De Goede, Branje, & Meeus, 2009; McNelles & Connolly, 1999; Radmacher & Azmitia, 2006). This finding raises the possibility that establishing truly close friendships in late adolescence may be a domain in which competence or lack thereof is particularly relevant for males.

In the final full path model tested, adolescent-era predictors accounted for almost 25% of the variance in adult romantic satisfaction even though predictors had been assessed anywhere from 10 to 15 years previously. The strength of these predictions suggests the importance of adolescence as a staging ground for the development of later romantic satisfaction. It also further emphasizes the importance of non-romantic relationships in adolescence, as this magnitude of prediction was obtained without reference to any actual romantic relationship behavior in adolescence. Notably, most of the variables that did directly tap aspects of actual adolescent romantic relationship behaviors were not predictive of long-term romantic satisfaction. Even romantic relationship quality at ages 17 to 19 failed to predict long-term satisfaction, perhaps reflecting that the underlying sources of romantic relationship quality at these ages (e.g., degree of mutual attraction, etc.) may differ from sources of friendship quality at that age. This finding is consistent with the perspective that though romantic competence is an emerging developmental task in adolescence, and not yet a primary developmental task (Roisman, et al., 2004). It should be kept in mind, of course, that the lack of significant findings does not show that these factors have no relation to future satisfaction, only that any actual predictive relation was not sizeable enough to be statistically reliably detectable. This was particularly true with regard to romantic relationship quality in late adolescence, which was assessed only for those adolescents (approximately two-thirds of the sample) who were in a sustained romantic relationship during that period. These findings are consistent with a perspective, however, that the key within adolescence to long-term romantic relationship satisfaction is most aptly described as being more closely linked to the relationship aspect than to the romantic aspect.

Nonetheless, the lack of predictions from adolescent romantic behavior is noteworthy given that both adolescents and parents often harbor considerable anxiety about physical attractiveness and about gaining romantic relationship experience in adolescence (Brown, 1999; Emmons, 1996). We found that none of the factors that appear most likely to be a point of focus in terms of romantic experience in adolescence—from the amount of general experience in romantic relationships, to sexual experience, to general physical attractiveness—were linked to future romantic satisfaction. This lack of findings, combined with evidence that relationship experiences in adolescence are often associated with negative outcomes, both behaviorally (e.g., pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections), and psychologically (e.g., depressive symptoms) (Davila, 2008; Sedgh, Finer, Bankole, Eilers, & Singh, 2015; Zimmer-Gembeck, et al., 2001), suggests that concerns about lack of early involvement in romantic relationships are likely to be unfounded. None of this is to say that romantic experience in adolescence is unimportant, but it does suggest that there may be a substantial difference between the competencies needed to gain romantic experience in adolescence and those that will serve as the basis for romantic satisfaction later in life.

Several qualifications to these findings also warrant note. Most importantly, although longitudinal studies such as this can serve to disconfirm causal hypotheses, they are not logically sufficient to establish the presence of causal processes. More specifically, it is possible that the significant predictors observed in part reflected other underlying, unmeasured competencies that account for the observed findings. It also remains an open question for future research as to just how much specificity there is in predictions from adolescent friendship competence (i.e., whether it predicts only to romantic competence or is linked to broader markers of long-term functioning such as academic or career competence). It should also be noted that for two of the measures in early- and mid-adolescence—positive peer expectations and social competence—self-reports were used, which likely inflated their relationship to later reported romantic satisfaction. Notably, however, the measures in late adolescence did not at all rely upon adolescent self-report: one was behavioral (was the same peer recruited to come in as a closest friend) and the other was based on peer-reports averaged across two years.; nor did the self-report measure of quality of an ongoing romantic relationship in late adolescence predict long-term relationship satisfaction. Finally, it should be noted that the age 27–30 period does not constitute an endpoint in romantic life development. Hence, even identifying factors that predict romantic life satisfaction over a long period, as in this study, can only set the stage for research examining predictors of such satisfaction farther into the life course.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (9R01 HD058305-16A1 & R01-MH58066).

References

- Allen JP, Loeb EL, Tan J, & Narr RK (2017). The body remembers: Adolescent conflict struggles predict adult interleukin-6 Levels. Development and Psychopathology, Online Version. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417001754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Miga EM (2010). Attachment in adolescence: A move to the level of emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 181–190. doi: 10.1177/0265407509360898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Tan J (2016). The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence In Cassidy J & Shaver P (Eds.), Handbook of Attachment, Third Edition (pp. 399–415). New York NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data In Schumaker GAMRE (Ed.), Advanced structural modeling: Issues and Techniques (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari M, Noah SBM, Hassan SAB, & Baba MB (2012). Comparison the effects of communication and conflict resolution skills training on marital satisfaction. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(1), 182. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert S, & Poulin F (2016). Romantic Relationship Patterns from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood: Associations with Family and Peer Experiences in Early Adolescence. J Youth Adolesc, 45(5), 945–958. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0435-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchey HA (2007). Perceived romantic competence, importance of romantic domains, and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(4), 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB (1999). “You’re going out with who?”: Peer group influences on adolescent romantic relationships In Furman W & Brown BB (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge studies in social and emotional development (pp. 291–329). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Motzoi C, & Meyer F (2009). Friendship as process, function, and outcome. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chango J, Allen JP, Szwedo DE, & Schad MM (2015). Early adolescent peer foundations of late adolescent and young adult psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(4), 685–699. doi: 10.1111/jora.12162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, & Sparrow SA (1981). Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86(2), 127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Kasen S, Chen H, Hartmark C, & Gordon K (2003). Variations in patterns of developmental transmissions in the emerging adulthood period. Developmental psychology, 39(4), 657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Laursen B (2000). Adolescent relationships: The art of fugue In Hendrick C & Hendrick SS (Eds.), Close relationships: A sourcebook (pp. 59–69). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & van Dulmen M (2006). The significance of middle childhood peer competence for work and relationships in early adulthood In Huston A. c. & Ripke M. k. (Eds.), Developmental contexts in middle childhood: Bridges to adolescence and adulthood (pp. 23–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, & McIsaac C (2011). Romantic relationships in adolescence. Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence, 3, 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Daniels K, Vespa J, & Mosher WD (2012). First Marriages in the United States: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports. Number 49. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J (2008). Depressive symptoms and adolescent romance: Theory, research, and implications. Child Development Perspectives, 2(1), 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- De Goede IH, Branje SJ, & Meeus WH (2009). Developmental changes and gender differences in adolescents’ perceptions of friendships. J Adolesc, 32(5), 1105–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M (2011). Sex differences in romantic attachment: a meta-analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Bull, 37(2), 193–214. doi: 10.1177/0146167210392789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons L (1996). The relationship of dieting to weight in adolescents. Adolescence, 31(121), 167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BJ, Rosenthal L, Donahoe CP, Schlundt DG, & McFall RM (1978). A social-behavioral analysis of skill deficits in delinquent and nondelinquent adolescent boys. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 46(6), 1448–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Collibee C (2014). A matter of timing: developmental theories of romantic involvement and psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychopathol, 26(4 Pt 1), 1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Wehner EA (1997). Adolescent romantic relationships: A developmental perspective In Shulman S & Collins WA (Eds.), Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives. New directions for child development, No. 78 (pp. 21–36). San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass Inc, Publishers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM (2014). What predicts divorce?: The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Overbeek G, & Engels RC (2010). Effects of attractiveness and social status on dating desire in heterosexual adolescents: An experimental study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(5), 1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare A, & Miga EM (2009). Adult Romantic Life Satisfaction. Unpublished Scale. University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1988). Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for adolescents. Denver, Colorado: University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS, Dicke A, & Hendrick C (1998). The relationship assessment scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS, & Hendrick C (2006). Measuring respect in close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23(6), 881–899. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnen C, Hagedoorn M, Ranchor AV, & Sanderman R (2008). Relationship satisfaction in women: A longitudinal case‐control study about the role of breast cancer, personal assertiveness, and partners’ relationship‐focused coping. British journal of health psychology, 13(4), 737–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn EE, Xu Y, Beam CR, Turkheimer E, & Emery RE (2013). Accounting for the physical and mental health benefits of entry into marriage: a genetically informed study of selection and causation. J Fam Psychol, 27(1), 30–41. doi: 10.1037/a0029803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, & Waite LJ (2009). Marital Biography and Health at Mid-Life∗. Journal of health and social behavior, 50(3), 344–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CM, Molden DC, & Finkel EJ (2013). Loving freedom: Concerns with promotion or prevention and the role of autonomy in relationship well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopera AA, Maier RA, & Johnson JE (1971). Perception of physical attractiveness: The influence of group interaction and group coaction on ratings of women. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Pederson A, Bunde M, Barry RA, Brock RL, Fazio E, Mulryan L, Hunt S, Madsen L, & Dzankovic S (2008). Objective ratings of relationship skills across multiple domains as predictors of marital satisfaction trajectories. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(3), 445–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzinger S, & Gordon KC (2005). Exploring relationships among communication, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 31(5), 409–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb EL, Tan JS, Hessel ET, & Allen JP (2016). Getting what you expect: Negative social expectations in early adolescence predict hostile romantic partners and friends Into adulthood. Journal of Early Adolescence, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNelles LR, & Connolly JA (1999). Intimacy between adolescent friends: Age and gender differences in intimate affect and intimate behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 9(2), 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard AD, & Offman A (2009). The interrelationships between sexual self-esteem, sexual assertiveness and sexual satisfaction. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18(1/2), 35. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD, & Jones J (2010). Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital and health statistics. Series 23, Data from the National Survey of Family Growth(29), 1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudekerk BA, Allen JP, Hessel ET, & Molloy LE (2015). The cascading development of autonomy and relatedness from adolescence to adulthood Child Development, 86(2), 472–485. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S, Sells JN, Giordano FG, & Tollerud TR (2007). Intimacy, differentiation, and personality variables as predictors of marital satisfaction. The family journal, 15(4), 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Patzer GL (1985). The physical attractiveness phenomena: Plenum Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Raby KL, Roisman GI, Fraley RC, & Simpson JA (2015). The Enduring Predictive Significance of Early Maternal Sensitivity: Social and Academic Competence Through Age 32 Years. Child Development, 86(3), 695–708. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radmacher K, & Azmitia M (2006). Are there gendered pathways to intimacy in early adolescents’ and emerging adults’ friendships? Journal of Adolescent Research, 21(4), 415–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental psychology, 49(11), 2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75(1), 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, & Burge D (1995). Cognitive representations of self, family, and peers in school-age children: Links with social competence and sociometric status. Child Development, 66(5), 1385–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL, & Grolnick WS (1995). Autonomy, relatedness, and the self: Their relation to development and psychopathology In Cicchetti DCDJ (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology (Vol. 1, pp. 618–655). New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sas Institute. (2015). SAS, Version 9.4. Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Bryant AL, & O’Malley PM (2004). Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and psychopathology, 16(4), 1119–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, & Singh S (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I (2003). Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 519–531. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, & Connolly J (2013). The Challenge of Romantic Relationships in Emerging Adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. doi: 10.1177/2167696812467330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. American journal of sociology, 107(4), 1065–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, & Salvatore JE (2011). The Impact of Early Interpersonal Experience on Adult Romantic Relationship Functioning: Recent Findings From the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(6), 355–359. doi: 10.1177/0963721411418468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins WA, Tran S, & Haydon KC (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: a developmental perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol, 92(2), 355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, & Jacobvitz D (1989). Diverging pathways, developmental transformations, multiple etiologies and the problem of continuity in development. Human Development, 32, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein L, McDonough P, Monette G, & Shao Q (2005). Marital transitions and mental health: are there gender differences in the short-term effects of marital status change? Social science & medicine, 61(11), 2293–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwedo DE, Chango JM, & Allen JP (2015). Adolescent Romance and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Effects of Positive Coping and Perceived Friendship Competence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(4), 538–550. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.881290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traupmann J, & Hatfield E (1981). Love and its effect on mental and physical health. Aging: Stability and change in the family, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen MHM, Goncy EA, Haydon KC, & Collins WA (2007). Distinctiveness of Adolescent and Emerging Adult Romantic Relationship Features in Predicting Externalizing Behavior Problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(3), 336–345. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9245-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vannatta K, Gartstein MA, Zeller M, & Noll RB (2009). Peer acceptance and social behavior during childhood and adolescence: How important are appearance, athleticism, and academic competence? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(4), 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Wade TJ, & Pevalin DJ (2004). Marital Transitions and Mental Health∗. Journal of health and social behavior, 45(2), 155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, & Sroufe LA (1983). Social competence as a developmental construct. Developmental Review, 3, 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Connolly J, & Segal ZV (2001). Intimacy in relationships and cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescent girls. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 25(4) August 2001), 477–496. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, & Petherick J (2006). Intimacy dating goals and relationship satisfaction during adolescence and emerging adulthood: Identity formation, age and sex as moderators. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(2), 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Siebenbruner J, & Collins WA (2001). Diverse aspects of dating: Associations with psychosocial functioning from early to middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 24(3), 313–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P (2004). Attachment representations and characteristics of friendship relations during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(1), 83–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]