Abstract

Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP) and X-linked Protoporphyria (XLP) are rare, genetic photodermatoses resulting from defects in enzymes of the heme-biosynthetic pathway. EPP results from the partial deficiency of ferrochelatase, and XLP results from gain-of-function mutations in erythroid specific ALAS2. Both disorders result in the accumulation of erythrocyte protoporphyrin, which is released in the plasma and taken up by the liver and vascular endothelium. The accumulated protoporphyrin is activated by sunlight exposure, generating singlet oxygen radical reactions leading to tissue damage and excruciating pain. About 2–5% of patients develop clinically significant liver dysfunction due to protoporphyrin deposition in bile and/or hepatocytes which can advance to cholestatic liver failure requiring transplantation.

Clinically these patients present with acute, severe, non-blistering phototoxicity within minutes of sun-exposure. Anemia is seen in about 47% of patients and about 27% of patients will develop abnormal serum aminotransferases. The diagnosis of EPP and XLP is made by detection of markedly increased erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels with a predominance of metal-free protoporphyrin. Genetic testing by sequencing the FECH or ALAS2 gene confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment is limited to sun-protection and there are no currently available FDA-approved therapies for these disorders. Afamelanotide, a synthetic analogue of α-melanocyte stimulating hormone was found to increase pain-free sun exposure and improve quality of life in adults with EPP. It has been approved for use in the European Union since 2014 and is not available in the U.S. In addition to the development of effective therapeutics, future studies are needed to establish the role of iron and the risks related to the development of hepatopathy in these patients.

Keywords: Porphyria, genetics, metabolic, heme-biosynthesis, photodermatosis

1. Introduction

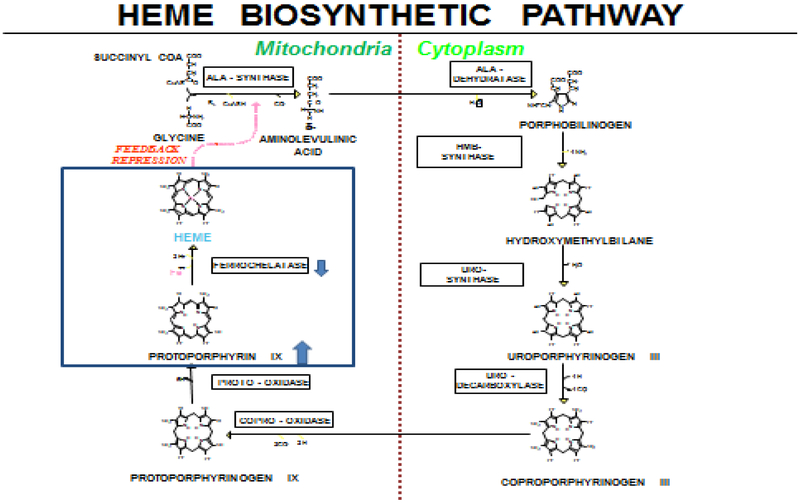

Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP) and X-linked Protoporphyria (XLP) are rare, genetic photodermatoses resulting in acute, painful, photoxicity on sun-exposure1. EPP results from the deficient activity of ferrochelatase, the final enzyme in the heme-biosynthetic pathway1 (Figure 1). XLP, a less common condition, results from gain-of-function mutations in erythroid-specific aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS2) gene2.

Figure 1.

Heme biosynthetic pathway

EPP is the most common porphyria in children, usually manifesting in infancy or early childhood after sun exposure with acute, painful photosensitivity1. The prevalence estimates of EPP range from 1:75,000 in the Netherlands to 1:200,000 in the United Kingdom3; 4. XLP accounts for about 2% of cases in Europe and approximately 10% of cases in the United States4; 5.

2. Pathophysiology

The deficiency of FECH or gain-of-function mutations in ALAS2 both result in the accumulation of protoporphyrin IX (PPIX)1; 2; 6. FECH is responsible for the insertion of iron into PPIX to generate the final product heme. When FECH is deficient to <30% enzyme activity, there is an increased accumulation of PPIX1. ALAS2 is highly expressed in erythroid tissues and provides a regulatory role in rate of erythroid heme biosynthesis. When this is disrupted in XLP, the rate of ALA formation is increased, and the insertion of iron into PPIX by FECH becomes rate-limiting for heme synthesis in erythroid tissues resulting in accumulation of protoporphyrin2; 6. Protoporphyrin is released from the bone marrow into the circulating erythrocytes and plasma where it is taken up by the liver and vascular endothelium including the superficial skin vasculature. The protoporphyrin molecules are photodynamic and absorb light radiation in visible blue-violet light in the Soret band and to a lesser degree in the long-wave UV region7; 8. When porphyrins absorb light they enter an excited energy state. This energy is presumably released as fluorescence and by formation of singlet oxygen and other oxygen radicals that can produce tissue and vessel damage secondary to activation of the complement system. The release of histamines, kinins, and chemotactic factors may mediate skin damage9. Accumulated hepatic protoporphyrin can precipitate in hepatocytes and bile canaliculi, causing hepatotoxicity, decreased bile formation and flow, and cholestatic liver failure in some patients10; 11.

3. Genetics

EPP is autosomal recessive in inheritance12. Around 96% of patients with EPP have a loss of function FECH mutation in trans with a second low-expression pathogenic variant c.315–48T>C (IVS3–48T>C)4; 5. The IVS3–48T>C allele creates a cryptic upstream acceptor site in intron 3 that modulates the alternative splicing of the normal FECH mRNA, resulting in FECH activity <30% of normal13; 14. The prevalence of EPP may vary based on the allele frequency of the low-expression allele, which ranges from approximately 1%−3% in Africans, 10% in Caucasians to approximately 43% in the Japanese population15. Rarely patients can inherit bi-allelic loss-of-function mutations in FECH. This accounts for about 4% of cases in Europe4.

Over 190 mutations have been reported in the FECH gene including, missense, nonsense, splicing and frameshift mutations16. EPP is 100% penetrant, males and females are equally affected12. Although the literature suggests that patients who are homozygous for the low expression allele are asymptomatic, a recent report from Japan identified three children homozygous for the common low expression IVS3–48T>C allele who had slightly elevated free protoporphyrin levels and a mild presentation of EPP17.

XLP results from gain-of-function mutations in erythroid-specific ALAS22. Mutations associated with XLP have only been observed in exon 11, which encodes the C-terminus, and result in a gain-of-function of ALAS2. These mutations result in stop or frameshift lesions that prematurely truncate or abnormally elongate the wild-type enzyme, leading to increased ALAS2 activity2; 5. In XLP, all males are affected18. In heterozygous females with XLP, the random X-inactivation pattern directly influences the penetrance and the severity of the phenotype. XLP females can be asymptomatic clinically with normal protoporphyrins, be asymptomatic clinically with slightly elevated protoporphyrin levels or have significant symptoms based on the pattern of X-inactivation18; 19.

About 4–6% of patients with the symptoms of EPP and elevated erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels will not have mutations in FECH or ALAS24; 20.

Recently, an autosomal dominant mutation in human CLPX, a modulator of heme biosynthesis, was found to result in the accumulation of protoporphyrin and symptoms of protoporphyria in an affected family21. Acquired somatic FECH mutations have been identified in a small number of patients in whom EPP has developed after the age of 40 years in association with myelodysplasia or myeloproliferative disorder22; 23. A case of late-onset EPP with myelodysplastic syndrome has also been reported in a patient who had the homozygous IVS3–48T>C polymorphism in the FECH gene24. Late onset XLP has also been reported in a case of early myelodysplastic syndrome with somatic mosaicism in the bone marrow25.

4. Clinical presentation

4.1. Cutaneous manifestations

EPP and XLP present with acute, painful phototoxicity on sun-exposure starting in infancy or childhood [1]. The mean age of symptom onset is about 4 years [20]. The pain is usually preceded by tingling, itching and burning sensation of the skin which may occur within minutes of sun exposure [9]. Patients can develop erythema and edema of the sun exposed skin [8] (Figure 2.). Vesicles or bullous lesions are uncommon in these disorders. Severe scarring, hypo or hyperpigmentation, skin friability and hirsutism are not typically seen9; 26. Blistering was self-reported by about 26% of patients in one large series [20].

Figure 2.

Clinical manifestations: Erythema and edema on the dorsum of hands and forearm seen after acute phototoxic episode.

The dorsum of the hands and face are most commonly affected but any sun exposed area can be affected. Patients may be more sensitive to sun exposure the day after an acute phototoxic phenomenon27. With chronic sun-exposure, patients may develop lichenification and grooving around the lips9. Palmar keratoderma has been reported in some individuals with two loss-of-function FECH mutations28.

EPP patients have significant clinical variability, with some patients who are unable to tolerate even a few minutes of sun exposure and others who can tolerate several hours20. Most patients develop symptoms within 30 minutes of sun exposure. The pain is severe and the symptoms may seem out of proportion to the skin lesions or lack thereof. The pain is not responsive to analgesics, including narcotic analgesics. Recovery from symptoms may take up to 4–7 days20. Symptoms may also vary based on environmental conditions including season, cloud cover, intensity and extent of sun-exposure and time of day29. With time, most patients are able to recognize the prodromal symptoms of EPP (e.g. itching and tingling) which serve as a warning sign to seek shade. Patients also develop a conditioned behavior of sun-avoidance which significantly impacts their daily activities.

4.2. Hepatobiliary disease

The excess protoporphyrin in EPP and XLP is excreted by the liver into the bile where it enters the enterohepatic circulation30. Progressive accumulation of protoporphyrin may occur in the liver when the biliary excretion does not keep pace with the load being presented to the liver. When hepatocellular damage reaches a critical stage, protoporphyrin accumulation will rapidly accelerate due to marked impairment of biliary excretion11; 12. Concomitant conditions such as viral hepatitis, excessive alcohol consumption, and use of drugs which induce cholestasis may contribute to worsening liver disease. End-stage liver disease is typically preceded by an elevation in plasma and erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels. Patients may also develop a motor neuropathy in the setting of liver failure31; 32.

The excess amounts of free protoporphyrin may become insoluble and aggregate in the hepatocytes and small biliary radicals leading to obstruction to bile flow and cholestasis. About 20–30% of patients with EPP will have elevations in serum aminotransferases20. Protoporphyrin in bile may also crystallize forming gallstones. In one series, cholelithiasis were seen in 23.5% of patients20.

4.3. Anemia

Mild anemia, typically microcytic anemia can be seen in EPP patients33. Patients with EPP appear to have an abnormal iron metabolism but the mechanism of iron deficiency is unclear34; 35. The etiology of microcytic anemia and low iron and ferritin levels in EPP patients is unknown36; 37. Previous studies suggest that EPP and XLP patients have normal iron absorption and an appropriate hepcidin response38. The iron deficiency in these disorders does not appear to be related to chronic inflammation or iron loss. The cause and mechanism of iron deficiency in these patients remains to be elucidated.

4.4. Vitamin D deficiency

EPP and XLP patients can develop vitamin D deficiency secondary to sun avoidance39; 40. A recent report showed that the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis is increased in patients in EPP41.

5. Diagnosis

5.1. Biochemical testing

The biochemical diagnosis of EPP is established by the detection of significantly elevated total erythrocyte protoporphyrin with a predominance (85%–100%) of metal-free protoporphyrin1; 13. Ferrochelatase can utilize metals other than iron and it catalyzes the conversion of the remainder of the protoporphyrin after hemoglobinization to zinc. As ferrochelatase is deficient in EPP, it limits the formation of both heme and zinc protoporphyrin42. In X-linked Protoporphyria, total erythrocyte protoporphyrin is also significantly increased with a lower fraction of metal-free protoporphyrin (50%–85% of the total) as ferrochelatase activity is normal in these patients42.

It is important to distinguish metal-free protoporphyrin from zinc-chelated protoporphyrin on laboratory testing, as several other conditions such as lead poisoning, iron deficiency, anemia of chronic disease, and various hemolytic disorders may lead to elevation of erythrocyte protoporphyrin, usually zinc protoporphyrin42. Plasma total porphyrins are also increased in EPP and XLP. If plasma porphyrins are increased, the fluorescence emission spectrum of plasma porphyrins at neutral pH can be characteristic at 632–634 nm and can distinguish EPP and XLP from other porphyrias42; 43.

5.2. Genetic testing

The diagnosis of EPP is confirmed by identification of biallelic mutations by sequencing the FECH gene44. Gene targeted deletion/duplication analysis maybe useful if only one pathogenic variant is found45. In XLP, ALAS2 sequencing confirms the diagnosis4; 5.

There is limited information about genotype-phenotype correlation in EPP and XLP. Recent studies have shown that protoporphyrin levels were significantly lower in patients with EPP compared to XLP males20. EPP patients with a missense mutation in the FECH gene have lower protoporphyrin levels compared to patients with FECH deletions, nonsense or splice site mutations. The higher the level of erythrocyte protoporphyrin, the more likely that the patient will be more severely symptomatic characterized by decreased sun tolerance and increased risk of liver dysfunction20. In addition, some studies suggest that severe FECH mutations on both alleles may have an increased risk for severe liver disease46–48.

6. Monitoring

Patients with EPP and XLP should have a comprehensive baseline evaluation on diagnosis and annual monitoring. The initial evaluation should include a comprehensive medical history including history of phototoxicity and a physical including thorough skin examination.

Baseline biochemical testing should include erythrocyte protoporphyrin including metal-free and zinc protoporphyrin levels. Plasma total porphyrins with the fluorescence spectrum can be helpful for confirming the diagnosis. All patients with an elevated protoporphyrin level with an excess of metal-free protoporphyrin should have genetic testing by sequencing the FECH and/or ALAS2 gene as biochemical results may not reliably differentiate between EPP and XLP20.

Additional laboratory testing should include a complete blood count to evaluate for anemia, and an iron profile including ferritin. Levels of vitamin D should be assessed to rule out any deficiency. Hepatic function panel including serum aminotransferases should be included to evaluate liver dysfunction. In patients with elevated liver enzymes, a more detailed work up is warranted to rule out other etiologies of liver dysfunction. Hepatic imaging with ultrasound is recommended if cholelithiasis is suspected. Newer diagnostic modalities such as Fibroscan may be helpful in assessing liver involvement in EPP and XLP; however, its utility has not been validated in these diseases. Liver biopsy may be indicated in some cases to evaluate for protoporphyric liver disease.

Patients with EPP and XLP should be recommended vaccination against hepatitis A and B to avoid preventable causes of liver injury. Vitamin D supplementation is recommended for patients who are deficient to avoid long term bone complications.

Patients and their families should be counseled about sun protection including the use of protective clothing. Annual follow up should be recommended and include laboratory studies including protoporphyrin levels.

Close monitoring is recommended for patients on iron therapy including complete blood count, iron indices and liver enzymes.

7. Management

7.1. Phototoxic reactions

Phototoxic reactions can be severe and do not respond to analgesics, including narcotic analgesics. Use of cold compresses or cold air on the sun exposed areas has been reported to help some patients. Oral corticosteroids and anti-histamines have been used to manage pain and swelling but the benefits are unclear.

7.2. Sun Protection

The mainstay of treatment for EPP is sun avoidance and/or sun protection. Most patients manage their disorder by modifying their lifestyle to limit sunlight exposure. Long sleeved clothing, gloves, wide brimmed hats and sun glasses can be used to minimize exposure to UV light. In addition, tinted windows can be used to prevent sun exposure while driving.

Topical sunscreens do not protect against phototoxic reactions as they are not formulated to protect against UVA and visible light. Sunscreens with opaque physical protective such as zinc oxide or titanium dioxide can provide some protection but may not cosmetically acceptable. A recent report showed benefits of a makeup base with photoprotective products designed for the protoporphyrin IX absorption spectrum in a small cohort of Japanese patients49.

Phototherapy with gradual exposure to artificial ultraviolet lights has been used to induce increased light tolerance over time50; 51. There have been no clinical trials to show an improvement in sun tolerance with phototherapy.

7.3. Drugs

Oral beta-carotene has been used to improve sun tolerance in patients. The dose depends on age and needs to be adjusted to maintain serum carotene at a level high enough to cause mild skin discoloration due to carotenemia52; 53. Other drugs such as n-acetyl cysteine, cysteine and vitamin C have also been tried in EPP. However, there are no data to support the efficacy of these treatments in EPP54. High dose cimetidine has been reported to benefit pediatric patients with EPP but there is no clear clinical data or mechanistic evidence supporting this therapy55; 56.

Afamelanotide (Scenesse), a subcutaneously administered implant, is a potent analogue of the human α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH). Afamelanotide binds to the melanocortin 1 receptor in dermal, increasing the production of eumelanin which is photoprotective57. The results of two multicenter, double-blind, placebo controlled, Phase 3 clinical trials in Europe and the U.S. showed an increase in pain free sun exposure in adult patients compared to controls. In the European study, there was a decreased number of phototoxic reactions in the afamelanotide group. In both trials, there was an improvement in quality of life with afamelanotide58. In a long term observational study over 8 years, afamelanotide was shown to be safe and well tolerated, with good clinical effectiveness and an improvement in quality of life59. Scenesse has been approved for use for adults with EPP by the European Medicines agency in December 2014. It is currently pending evaluation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

7.4. Liver disease

Hepatic complications can be seen in a small subset of EPP patients. In about 1–5% of patients, this may progressive to cholestatic liver failure requiring transplantation11; 30. Liver transplant is the treatment for end-stage liver disease secondary to protoporphyrin related liver damage31; 60. However, liver transplant is not curative as the primary source of protoporphyrin production is the bone marrow and liver transplant does not correct the underlying genetic defect32. Patients with EPP may develop a proximal motor neuropathy before or after liver transplant and require close monitoring. Bile acid sequestrants such as cholestyramine and other drugs such as ursodeoxycholelic acid have been used to increase the excretion of protoporphyrin through the biliary system32; 61. Plasmapheresis, red cell exchange transfusion and intravenous hemin have also been used to decrease protoporphyrin levels before liver transplant although the effectiveness of these therapies has not been established62; 63.

EPP patients can develop skin and tissue burns during surgery for liver transplant due to activation of protoporphyrin by light in the blue-violet region. Use of special filters which block wavelengths below 470 nm is recommended during liver transplantation surgery60.

There have been 62 liver transplants for pediatric and adult EPP patients reported32. Re-transplantation was needed in 7 cases. Post-transplant survival ranged from 47–66% at 10 year follow up32.

7.5. Bone marrow transplant

Bone marrow transplant can be curative and sequential liver and bone marrow transplant has been successful in curing protoporphyric liver disease64. There have been several reports of pediatric patients receiving a bone marrow transplant following a liver transplant65.

Wahlin et al. reported an adult with EPP who received a bone marrow transplant after medical management and reversal of cholestatic liver disease. A 2 year old with XLP and stage IV fibrosis also received a bone marrow transplant which stabilized liver disease66. Recently, a sequential liver and bone marrow transplant was reported in a 26 year old male with protoporphyric liver failure resulting in complete resolution of symptoms and normalization of protoporphyrin levels67. These reports suggest that in patients with liver disease who respond to medical management and have minimal fibrosis, bone marrow transplant may be performed without a need for liver transplant.

7.6. Iron supplementation in EPP and XLP

The role of iron metabolism in EPP and XLP is unclear. Microcytic anemia and low iron and ferritin levels can be seen in EPP patients; however, the etiology is unknown36; 37. Previous studies suggest that EPP and XLP patients have normal iron absorption and an appropriate hepcidin response38. The iron deficiency in these disorders does not appear to be related to chronic inflammation or iron loss. The cause and mechanism of iron deficiency in these patients remains to be elucidated.

Clinical observations from previous case reports support that iron supplementation in XLP improves protoporphyrin levels and anemia and may help prevent progression of liver disease68. In EPP patients, iron therapy has been reported to both exacerbate and improve EPP symptoms36; 69. These observations have been based on single case reports with limited monitoring and anecdotal reports of symptomatic improvement. Ongoing clinical trials looking at the role of iron in EPP and XLP may help with determining the effects of iron therapy in these patients.

8. Conclusions

EPP and XLP are rare photodermatoses with significant clinical heterogeneity. In addition to the development of effective therapeutics, future studies are needed to establish the risks related to the development of hepatopathy and the role of iron metabolism in these patients.

Funding

This research was supported in part by The Porphyrias Consortium (U54DK083909), which is a part of the NCATS Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). RDCRN is an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, funded through a collaboration between NCATS and the NIDDK. MB is supported in part by the NIH Career Development Award (K23DK095946).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson KE, Sassa S, Bishop DF, and Desnick RJ (2001). Disorders of Heme Biosynthesis: X-Linked Sideroblastic Anemia and the Porphyrias In The Metabolic and Molecurlar Bases of Inherited Disease, Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, and Valle D, eds. (New York, McGraw-Hill: ), pp 2961–3062. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whatley SD, Ducamp S, Gouya L, Grandchamp B, Beaumont C, Badminton MN, Elder GH, Holme SA, Anstey AV, Parker M, et al. (2008). C-terminal deletions in the ALAS2 gene lead to gain of function and cause X-linked dominant protoporphyria without anemia or iron overload. Am J Hum Genet 83, 408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elder G, Harper P, Badminton M, Sandberg S, and Deybach JC (2013). The incidence of inherited porphyrias in Europe. J Inherit Metab Dis 36, 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whatley SD, Mason NG, Holme SA, Anstey AV, Elder GH, and Badminton MN (2010). Molecular epidemiology of erythropoietic protoporphyria in the U.K. The British journal of dermatology 162, 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balwani M, Doheny D, Bishop DF, Nazarenko I, Yasuda M, Dailey HA, Anderson KE, Bissell DM, Bloomer J, Bonkovsky HL, et al. (2013). Loss-of-function ferrochelatase and gain-of-function erythroid-specific 5-aminolevulinate synthase mutations causing erythropoietic protoporphyria and x-linked protoporphyria in North American patients reveal novel mutations and a high prevalence of X-linked protoporphyria. Molecular medicine 19, 26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manceau H, Gouya L, and Puy H (2017). Acute hepatic and erythropoietic porphyrias: from ALA synthases 1 and 2 to new molecular bases and treatments. Current opinion in hematology 24, 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poh-Fitzpatrick MB (1978). Erythropoietic protoporphyria. International journal of dermatology 17, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecha M, Puy H, and Deybach JC (2009). Erythropoietic protoporphyria. Orphanet J Rare Dis 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poh-Fitzpatrick MB (2000). Porphyrias: photosensitivity and phototherapy. Methods Enzymol 319, 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomer JR (1988). The liver in protoporphyria. Hepatology 8, 402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloomer JR (1997). Hepatic protoporphyrin metabolism in patients with advanced protoporphyric liver disease. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 70, 323–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balwani M, Bloomer J, and Desnick R (2017). Erythropoietic Protoporphyria, Autosomal Recessive In GeneReviews((R)), Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, and Amemiya A, eds. (Seattle (WA: ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouya L, Puy H, Lamoril J, Da Silva V, Grandchamp B, Nordmann Y, and Deybach JC (1999). Inheritance in erythropoietic protoporphyria: a common wild-type ferrochelatase allelic variant with low expression accounts for clinical manifestation. Blood 93, 2105–2110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouya L, Puy H, Robreau AM, Bourgeois M, Lamoril J, Da Silva V, Grandchamp B, and Deybach JC (2002). The penetrance of dominant erythropoietic protoporphyria is modulated by expression of wildtype FECH. Nat Genet 30, 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouya L, Martin-Schmitt C, Robreau AM, Austerlitz F, Da Silva V, Brun P, Simonin S, Lyoumi S, Grandchamp B, Beaumont C, et al. (2006). Contribution of a common single-nucleotide polymorphism to the genetic predisposition for erythropoietic protoporphyria. American journal of human genetics 78, 2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS, Abeysinghe S, Krawczak M, and Cooper DN (2003). Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat 21, 577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizawa M, Makino T, Nakano H, Sawamura D, and Shimizu T (2016). Incomplete erythropoietic protoporphyria caused by a splice site modulator homozygous IVS3–48C polymorphism in the ferrochelatase gene. The British journal of dermatology 174, 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balwani M, Bloomer J, and Desnick R (1993). X-Linked Protoporphyria In GeneReviews((R)), Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, and Amemiya A, eds. (Seattle (WA: ). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brancaleoni V, Balwani M, Granata F, Graziadei G, Missineo P, Fiorentino V, Fustinoni S, Cappellini MD, Naik H, Desnick RJ, et al. (2016). X-chromosomal inactivation directly influences the phenotypic manifestation of X-linked protoporphyria. Clinical genetics 89, 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balwani M, Naik H, Anderson KE, Bissell DM, Bloomer J, Bonkovsky HL, Phillips JD, Overbey JR, Wang B, Singal AK, et al. (2017). Clinical, Biochemical, and Genetic Characterization of North American Patients With Erythropoietic Protoporphyria and X-linked Protoporphyria. JAMA dermatology 153, 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yien YY, Ducamp S, van der Vorm LN, Kardon JR, Manceau H, Kannengiesser C, Bergonia HA, Kafina MD, Karim Z, Gouya L, et al. (2017). Mutation in human CLPX elevates levels of delta-aminolevulinate synthase and protoporphyrin IX to promote erythropoietic protoporphyria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, E8045–E8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blagojevic D, Schenk T, Haas O, Zierhofer B, Konnaris C, and Trautinger F (2010). Acquired erythropoietic protoporphyria. Annals of hematology 89, 743–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aplin C, Whatley SD, Thompson P, Hoy T, Fisher P, Singer C, Lovell CR, and Elder GH (2001). Late-onset erythropoietic porphyria caused by a chromosome 18q deletion in erythroid cells. J Invest Dermatol 117, 1647–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki H, Kikuchi K, Fukuhara N, Nakano H, and Aiba S (2017). Case of late-onset erythropoietic protoporphyria with myelodysplastic syndrome who has homozygous IVS3–48C polymorphism in the ferrochelatase gene. The Journal of dermatology 44, 651–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livideanu CB, Ducamp S, Lamant L, Gouya L, Rauzy OB, Deybach JC, Paul C, Puy H, and Marguery MC (2013). Late-onset X-linked dominant protoporphyria: an etiology of photosensitivity in the elderly. The Journal of investigative dermatology 133, 1688–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thapar M, and Bonkovsky HL (2008). The diagnosis and management of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Gastroenterology & hepatology 4, 561–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poh-Fitzpatrick MB (1989). The “priming phenomenon” in the acute phototoxicity of erythropoietic protoporphyria. J Am Acad Dermatol 21, 311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minder EI, Schneider-Yin X, Mamet R, Horev L, Neuenschwander S, Baumer A, Austerlitz F, Puy H, and Schoenfeld N (2010). A homoallelic FECH mutation in a patient with both erythropoietic protoporphyria and palmar keratoderma. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 24, 1349–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bataille S, Dutartre H, Puy H, Deybach JC, Gouya L, Raffray E, Pithon M, Stalder JF, Nguyen JM, and Barbarot S (2016). Influence of meteorological data on sun tolerance in patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria in France. The British journal of dermatology 175, 768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anstey AV, and Hift RJ (2007). Liver disease in erythropoietic protoporphyria: insights and implications for management. Postgrad Med J 83, 739–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuire BM, Bonkovsky HL, Carithers RL Jr., Chung RT, Goldstein LI, Lake JR, Lok AS, Potter CJ, Rand E, Voigt MD, et al. (2005). Liver transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria liver disease. Liver Transpl 11, 1590–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singal AK, Parker C, Bowden C, Thapar M, Liu L, and McGuire BM (2014). Liver transplantation in the management of porphyria. Hepatology 60, 1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahlin S, Floderus Y, Stal P, and Harper P (2011). Erythropoietic protoporphyria in Sweden: demographic, clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics. J Intern Med 269, 278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holme SA, Worwood M, Anstey AV, Elder GH, and Badminton MN (2007). Erythropoiesis and iron metabolism in dominant erythropoietic protoporphyria. Blood 110, 4108–4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyoumi S, Abitbol M, Andrieu V, Henin D, Robert E, Schmitt C, Gouya L, de Verneuil H, Deybach JC, Montagutelli X, et al. (2007). Increased plasma transferrin, altered body iron distribution, and microcytic hypochromic anemia in ferrochelatase-deficient mice. Blood 109, 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holme SA, Thomas CL, Whatley SD, Bentley DP, Anstey AV, and Badminton MN (2007). Symptomatic response of erythropoietic protoporphyria to iron supplementation. J Am Acad Dermatol 56, 1070–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barman-Aksoezen J, Girelli D, Aurizi C, Schneider-Yin X, Campostrini N, Barbieri L, Minder EI, and Biolcati G (2017). Disturbed iron metabolism in erythropoietic protoporphyria and association of GDF15 and gender with disease severity. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 40, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bossi K, Lee J, Schmeltzer P, Holburton E, Groseclose G, Besur S, Hwang S, and Bonkovsky HL (2015). Homeostasis of iron and hepcidin in erythropoietic protoporphyria. Eur J Clin Invest 45, 1032–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holme SA, Anstey AV, Badminton MN, and Elder GH (2008). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in erythropoietic protoporphyria. The British journal of dermatology 159, 211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spelt JM, de Rooij FW, Wilson JH, and Zandbergen AA (2010). Vitamin D deficiency in patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 33 Suppl 3, S1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biewenga M, Matawlie RHS, Friesema ECH, Koole-Lesuis H, Langeveld M, Wilson JHP, and Langendonk JG (2017). Osteoporosis in patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria. The British journal of dermatology 177, 1693–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gou EW, Balwani M, Bissell DM, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Desnick RJ, Naik H, Phillips JD, Singal AK, Wang B, et al. (2015). Pitfalls in Erythrocyte Protoporphyrin Measurement for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Protoporphyrias. Clin Chem 61, 1453–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enriquez de Salamanca R, Sepulveda P, Moran MJ, Santos JL, Fontanellas A, and Hernandez A (1993). Clinical utility of fluorometric scanning of plasma porphyrins for the diagnosis and typing of porphyrias. Clin Exp Dermatol 18, 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rufenacht UB, Gouya L, Schneider-Yin X, Puy H, Schafer BW, Aquaron R, Nordmann Y, Minder EI, and Deybach JC (1998). Systematic analysis of molecular defects in the ferrochelatase gene from patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Am J Hum Genet 62, 1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whatley SD, Mason NG, Holme SA, Anstey AV, Elder GH, and Badminton MN (2007). Gene dosage analysis identifies large deletions of the FECH gene in 10% of families with erythropoietic protoporphyria. The Journal of investigative dermatology 127, 2790–2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whatley SD, Mason NG, Khan M, Zamiri M, Badminton MN, Missaoui WN, Dailey TA, Dailey HA, Douglas WS, Wainwright NJ, et al. (2004). Autosomal recessive erythropoietic protoporphyria in the United Kingdom: prevalence and relationship to liver disease. Journal of medical genetics 41, e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minder EI, Gouya L, Schneider-Yin X, and Deybach JC (2002). A genotypephenotype correlation between null-allele mutations in the ferrochelatase gene and liver complication in patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 48, 91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarkany RP, and Cox TM (1995). Autosomal recessive erythropoietic protoporphyria: a syndrome of severe photosensitivity and liver failure. Qjm 88, 541–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teramura T, Mizuno M, Asano H, Naru E, Kawara S, Kamide R, and Kawada A (2018). Prevention of photosensitivity with action spectrum adjusted protection for erythropoietic protoporphyria. The Journal of dermatology 45, 145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sivaramakrishnan M, Woods J, and Dawe R (2014). Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy in erythropoietic protoporphyria: case series. The British journal of dermatology 170, 987–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Todd DJ (2000). Therapeutic options for erythropoietic protoporphyria. The British journal of dermatology 142, 826–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anstey AV (2002). Systemic photoprotection with alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) and beta-carotene. Clinical and experimental dermatology 27, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathews-Roth MM, Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Harber LH, and Kass EH (1977). Beta carotene therapy for erythropoietic protoporphyria and other photosensitivity diseases. Archives of dermatology 113, 1229–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minder EI, Schneider-Yin X, Steurer J, and Bachmann LM (2009). A systematic review of treatment options for dermal photosensitivity in erythropoietic protoporphyria. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 55, 84–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tu JH, Sheu SL, and Teng JM (2016). Novel Treatment Using Cimetidine for Erythropoietic Protoporphyria in Children. JAMA dermatology 152, 1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langendonk JG, and Wilson J (2017). Insufficient evidence of cimetidine benefit in protoporphyria. JAMA dermatology 153, 237–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minder EI (2010). Afamelanotide, an agonistic analog of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, in dermal phototoxicity of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 19, 1591–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Langendonk JG, Balwani M, Anderson KE, Bonkovsky HL, Anstey AV, Bissell DM, Bloomer J, Edwards C, Neumann NJ, Parker C, et al. (2015). Afamelanotide for Erythropoietic Protoporphyria. The New England journal of medicine 373, 48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biolcati G, Marchesini E, Sorge F, Barbieri L, Schneider-Yin X, and Minder EI (2015). Long-term observational study of afamelanotide in 115 patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Br J Dermatol 172, 1601–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wahlin S, Stal P, Adam R, Karam V, Porte R, Seehofer D, Gunson BK, Hillingso J, Klempnauer JL, Schmidt J, et al. (2011). Liver transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria in Europe. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society 17, 1021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gross U, Frank M, and Doss MO (1998). Hepatic complications of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 14, 52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reichheld JH, Katz E, Banner BF, Szymanski IO, Saltzman JR, and Bonkovsky HL (1999). The value of intravenous heme-albumin and plasmapheresis in reducing postoperative complications of orthotopic liver transplantation for erythropoietic protoporphyria. Transplantation 67, 922–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eichbaum QG, Dzik WH, Chung RT, and Szczepiorkowski ZM (2005). Red blood cell exchange transfusion in two patients with advanced erythropoietic protoporphyria. Transfusion 45, 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wahlin S, and Harper P (2010). The role for BMT in erythropoietic protoporphyria. Bone Marrow Transplant 45, 393–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rand EB, Bunin N, Cochran W, Ruchelli E, Olthoff KM, and Bloomer JR (2006). Sequential liver and bone marrow transplantation for treatment of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Pediatrics 118, e1896–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahlin S, Aschan J, Bjornstedt M, Broome U, and Harper P (2007). Curative bone marrow transplantation in erythropoietic protoporphyria after reversal of severe cholestasis. J Hepatol 46, 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Windon AL, Tondon R, Singh N, Abu-Gazala S, Porter DL, Russell JE, Cook C, Lander E, Smith G, Olthoff KM, et al. (2018). Erythropoietic protoporphyria in an adult with sequential liver and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A case report. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons 18, 745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Landefeld C, Kentouche K, Gruhn B, Stauch T, Rossler S, Schuppan D, Whatley SD, Beck JF, and Stolzel U (2016). X-linked protoporphyria: Iron supplementation improves protoporphyrin overload, liver damage and anaemia. Br J Haematol 173, 482–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bentley DP, and Meek EM (2013). Clinical and biochemical improvement following low-dose intravenous iron therapy in a patient with erythropoietic protoporphyria. Br J Haematol 163, 289–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]