Abstract

Rectal injuries are rare sequelae of blunt force abdominal trauma and are notorious for delayed recognition with resulting high morbidity and mortality. The management of traumatic colorectal injury is mired in old dogma and until recently mandated faecal diversion. Here we present a case of extraperitoneal rectal perforation successfully managed conservatively following blunt trauma.

Keywords: Abdominal trauma, Extraperitoneal rectal injury, PR bleeding, Conservative management

Case report

A 35-year-old man wearing a helmet and full protective gear was ejected from his motorbike following collision with a van at 70 km/h. The subject bounced off the bonnet of the colliding vehicle and landed through the windscreen of a second vehicle. He denied loss of consciousness on impact, self-extricated and ambulated on scene briefly prior to a vasovagal episode. There was no prehospital hypotension en-route to our receiving level 2 trauma centre.

His primary survey was unremarkable with normal vital signs and a Glasgow Coma Sore of 15. A chest x-ray revealed a small left apical pneumothorax which was managed conservatively. Pelvic X-ray and extended focused abdominal sonography were normal. Secondary survey revealed a soft and non-tender abdomen devoid of stigmata of bruising. Per rectal (PR) examination was normal with an absence of peri-anal bruising, rectal mucosal defects or blood. A 5 mm superficial laceration to the left hemiscrotum was noted under two small puncture marks traversing his protective pants.

Laboratory investigations were unremarkable (haemoglobin 151 g/L, white cell count 4.39 × 109/L, platelets 240 × 109/L, INR 1.0, ALT 29 U/L, lipase 18 U/L). Computed tomography (CT) of the brain and cervical spine were performed due to mechanism in accordance with Canadian CT rules and excluded injury [1,2]. Abdominal CT was not performed given the absence of localising abdominal signs, normal haemodynamics and laboratory studies in accordance with local hospital guidelines. A scrotal ultrasound showed two small extra-testicular haematomas.

The patient was admitted for observation with a superficial scrotal injury closed following local exploration. A tertiary survey the following day revealed buttock and perianal bruising with small volume painless PR bleeding. A portal venous abdominal CT scan demonstrated gas contained in the scrotum and tracking into the mesorectal fat, sigmoid colon as well as the small bowel mesentery and as high as the gastroesophageal junction, posterior to the distal oesophagus and mediastinum. There was no free gas or fluid and the patient remained clinically well with no abdominal pain or features of sepsis (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

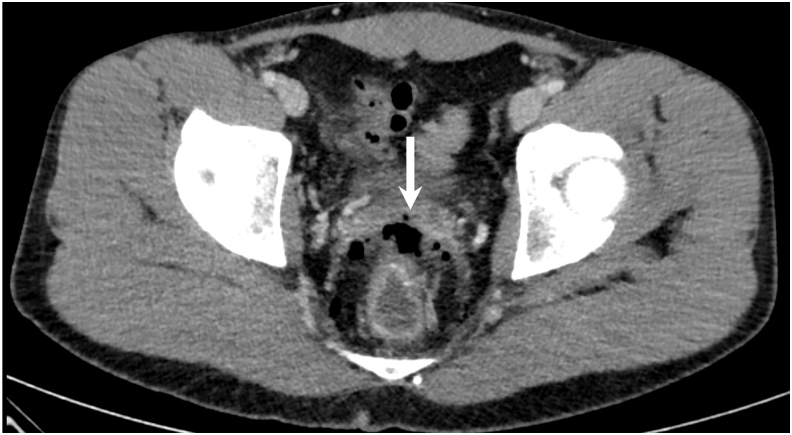

Fig. 1.

Gas contained in soft tissue anterior to rectum (arrow)

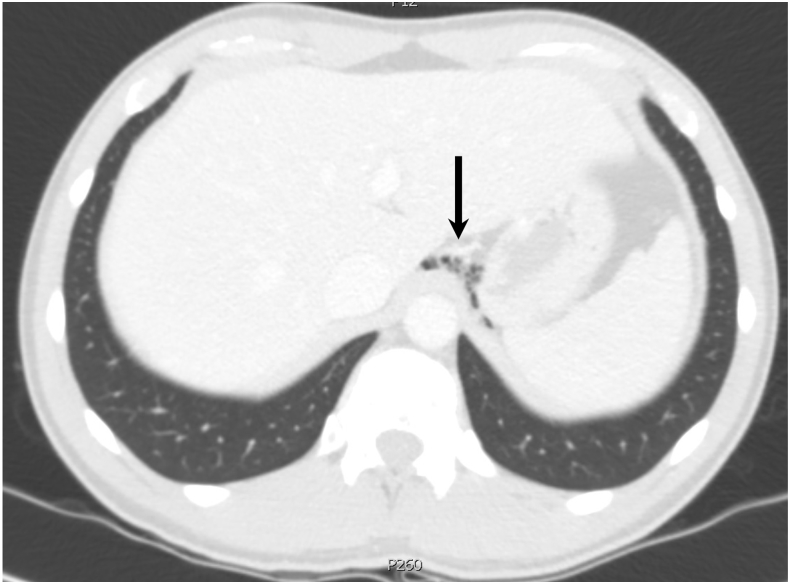

Fig. 2.

Contained gas at level of oesophageal hiatus (arrow).

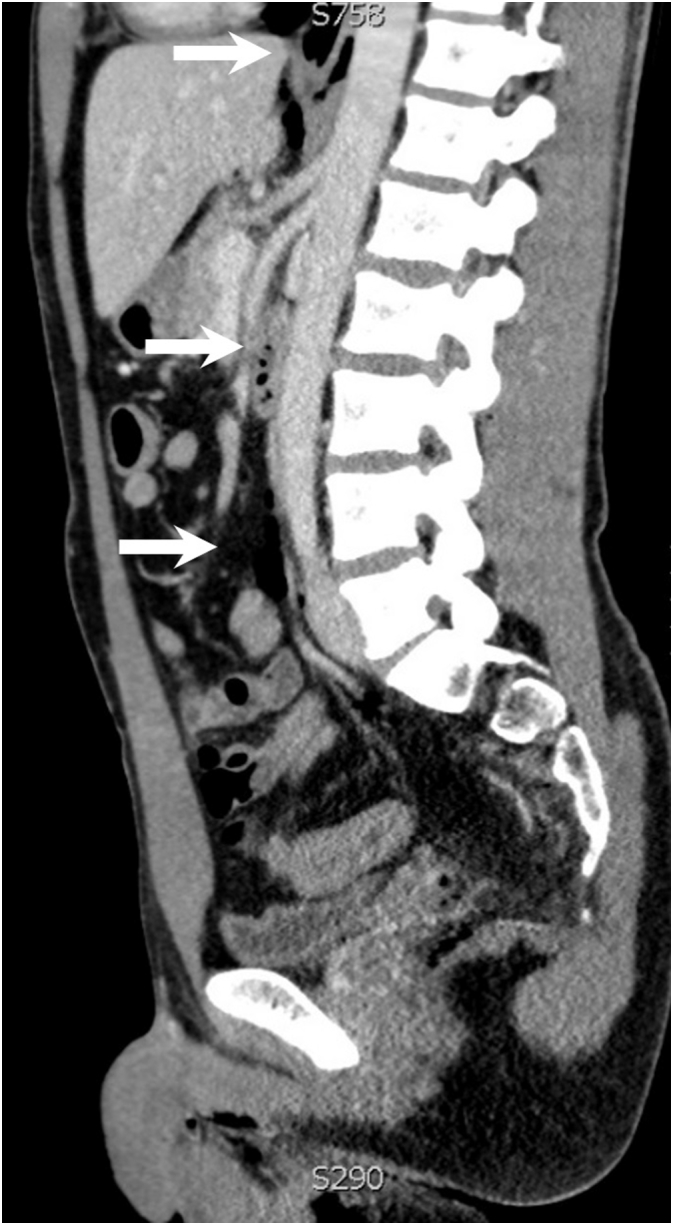

Fig. 3.

Contained gas tracking up small bowel mesentery (arrows).

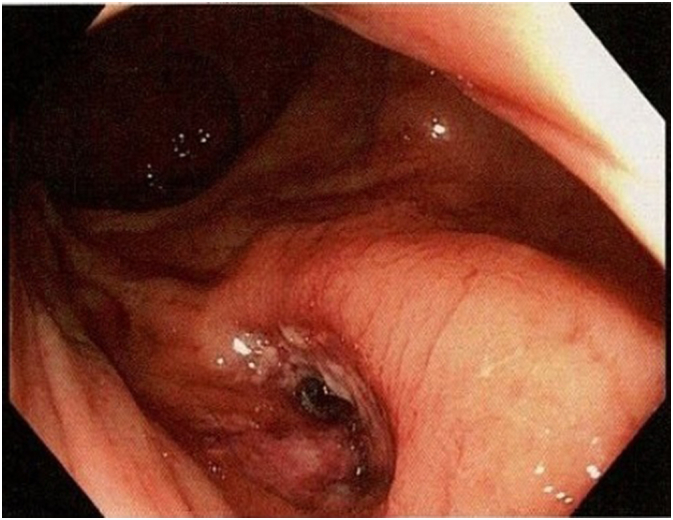

Further investigation with flexible sigmoidoscopy identified an isolated full-thickness tear in the posterior rectal wall 2 cm proximal to the dentate lineFig.4 In view of the patient's persisting systemic wellness he was managed conservatively with prophylactic antibiotics and serial abdominal examination. He remained well throughout his six-day admission with resolution of PR bleeding and unremarkable serial abdominal examination and blood tests. On follow-up one week later he remained well without further PR bleeding or abdominal symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Rectal perforation seen on flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Discussion

The rectum is the least frequently injured organ in trauma with an incidence of 0.1–0.5% and its management informed largely by military experience of penetrating injuries [3]. Historically the operative interventions for rectal injury were represented by the 4D's (direct repair, diversion, distal rectal washout, presacral drainage) with proximal diversion being the default treatment of choice.

Recent evidence has led to the decline of proximal diversion as the gold standard of treatment and has been superseded by primary repair in most cases. The AAST previously outlined the Rectal Injury Score grading injuries I-V based on presence of isolated haematoma or partial thickness laceration; laceration <50% or >50% rectal wall circumference; full thickness laceration extending into the perineum or presence of devitalised tissue [4].

The emergent change in attitude favouring primary repair is based on a previous landmark study of civilian colonic injuries which demonstrated longer hospital stay, higher mortality and increased morbidity including infective complications, acute renal failure and abdominal compartment syndrome in simple colonic injuries treated with diversion. To this end Miller et al. (2002) proposed a clinical pathway based on presence of a simple or destructive lesion (involvement of >50% colonic circumference or devascularisation) [5]. Destructive or complicated colonic injuries, including those with associated massive bleeding or significant medical comorbidities, require resection with or without diversion [6]. The anatomical location of injury also influences the operative approach and outcome. Intraperitoneal rectal injuries can be managed as in colonic injury and safely repaired primarily with diversion reserved for situations of high anastomotic leak risk including destructive injuries requiring more than six units of blood or underlying significant co-morbidities [7,8].

Few studies have specifically focused on the management of extraperitoneal rectal trauma. Brown et al. (2018) recently published the largest retrospective multicentre series of 459 traumatic extraperitoneal rectal injuries comparing outcomes of proximal diversion and primary repair. There was a total of 109 non-destructive injuries not treated with proximal diversion (grade I 64%; grade II 28%). Interestingly, 61% of this group received no treatment at all, including 26 grade II injuries. Non-destructive injuries accounted for 71% of lesions in the diversion group (grade I 16%; grade II 55%) and overall this group experienced more abdominal complications in addition to presacral drainage and distal washout being independent risk factors for abdominal complications. Unfortunately, it is not known why grade I injuries were diverted. Nevertheless, the apparent successful conservative management of 26 grade II injuries is intriguing [9].

In appropriately selected patients, healing by second intention of traumatic extraperitoneal rectal wounds is certainly possible [[10], [11], [12]]. Conservative management of full thickness transanal wounds post resection of rectal cancer and iatrogenic rectal injuries from retroflexion during colonoscopy have previously been described [[13], [14], [15]]. In a 2006 case series, Gonzalez et al. detailed successful conservative management of 14 patients with non-destructive penetrating extraperitoneal rectal injuries, none of whom required diversion or pre-sacral drainage. Barium enema performed on day 10 confirmed successful healing in all 14 patients and there were no cases of pelvic/pre-sacral abscess formation [16].

Our patient sustained an extraperitoneal laceration to the posterior rectal wall located proximal to the dentate line. Given the absence of penetrating trauma to the pelvis or rectum this is an unusual injury. We suggest the momentum of rapid deceleration propagated on impact generated shear waves with sufficient energy to cause full thickness disruption of the posterior rectal wall at the interface of the mobile rectum and its fixed segment at Waldeyer's fascia anchoring the lower rectum to the sacrum. The presence of contained gas as far cranially as the mediastinum further supports an axial conduction of force.

On initial assessment the rectal injury was not identified on PR exam despite being located near the dentate line. Our centre employs a selective imaging protocol guided by clinical or biochemical findings to minimise unnecessary radiation, especially in younger patients. Whilst it may be argued that abdominal CT performed on presentation may have achieved an earlier diagnosis it is unlikely to have altered management and avoided unnecessary surgery. The limited value of PR exam in rectal trauma is well documented in a previous retrospective review with two thirds of rectal injuries missed on PR exam [17]. Sigmoidoscopy has previously identified 70% of extraperitoneal rectal injuries despite negative PR exam (94% sensitivity) with CT having comparatively poorer sensitivity of 34%. The authors concluded that proctoscopy should be performed where there is suspicion of rectal trauma [18,19].

Conclusion

Traumatic rectal injury overall is uncommon, yet when present is often missed on initial assessment. Rectal examination is not reliable on its own as a negative PR exam does not rule out rectal injury, particularly where other suspicious features such as rectal bleeding or perineal bruising are present. This case highlights the difficulty in recognising traumatic rectal injury and the importance of observation in stable blunt abdominal trauma patients. There is a lack of consensus on the optimal management of traumatic rectal injuries in general. Conservative management of iatrogenic rectal injury has been described but its utility in the setting of trauma has not been evaluated. Whilst we are not advocating for routine conservative management of grade II (non-destructive) extraperitoneal injuries, our case study in addition to other published works suggest it may be appropriate in limited circumstances with appropriate case selection. Further work is needed to better assess the safety and limits of conservative management of traumatic grade II extraperitoneal injuries.

No financial support was provided in the preparation of this article. No conflicts of interest arose in the preparation of this article.

Acknowledgements

School of Medicine and Surgery, The University of Notre Dame, 32 Mouat Street, Fremantle WA, Western Australia, 6160, Australia

References

- 1.Stiell I.G., Wells G.A., Vandemheen K., Clement C.M., Lesiuk H., De Maio V.J., Laupacis A., Schull M., McKnight R.D., Verbeek R., Brison R., Cass D., Dreyer J., Eisenhauer M.A., Greenberg G.H., MacPhail I., Morrison L., Reardon M., Worthington J. The Canadian Cervical Spine Radiography rule for alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1841–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiell I.G., Wells G.A., Vandemheen H., Clement C., Lesiuk H., Laupacis A., McKnight D., Verbeek R., Brison R., Cass D., Eisenhauer M.A., Greenberg GH & Worthington J for the CCC Study Group The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001;357:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MD, Watts D, Fakhry S. Colon injury after blunt abdominal trauma: results of the EAST Multi-Institutional Hollow Viscus Injury Study. J. Trauma 2203;55;906–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Moore E.E., Cogbill T.H., Malangoni M.A., Jurkovich G.J., Champion H.R., Gennarelli T.A., McAninch J.W., Pachter H.L., Shackford S.R., Trafton P.G. Organ injury scaling, II: pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J. Trauma. 1990;30:1427–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller P.R., Fabian T.C., Croce M.A. Improving outcomes following penetrating colon wounds: application of a clinical pathway. Ann. Surg. 2002;235:775–781. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatch Q., Causey M., Martin M. Outcomes after colon trauma in the 21st century: an analysis of the US National Trauma Data Bank. Surgery. 2003;154:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg J.A., Fabian T.C., Magnotti L.J., Minard G., Bee T.K., Edwards N., Claridge J.A., Croce M.A. Penetrating rectal trauma: management by anatomic distinction improves outcome. Trauma. 2006;60:508–514. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000205808.46504.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart R.M., Fabian T.C., Croce M.A., Pritchard F.E., Minard G., Kudsk K.A. Is resection with primary anastomosis following destructive colon wound always safe? Am. J. Surg. 1994;168:316–319. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown C.V.R., Teixeira P.G., Furay E., Sharpe J.P., Musonza T., Holcomb J., Bui E., Bruns B., Hopper H.A., Truitt M.S., Burlew C.C., Schellenberg M., Sava J., VanHorn J., Eastridge B., Cross A.M., Vasak R., Vercruysse G., Curtis E.E., Haan J., Coimbra R., Bohan P., Gale S., Bendix P.G., the AAST Contemporary Management of Rectal Injuries Study Group Contemporary management of rectal injuries at Level I trauma centres: the results of an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma multi-institutional study. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:225–233. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burch J.M., Feliciano D.V., Mattox K.L. Colostomy and drainage for civilian rectal injuries: is that all? Ann. Surg. 1989;209:600–610. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198905000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunner R.G., Shatney C.H. Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of rectal trauma, blunt versus penetrating. Am. Surg. 1987;53:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore E.E., Dunn E.L., Moore J.B., Thompson J.S. Penetrating trauma index. J. Trauma. 1981;21:439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey H.R., Huval W.V., Max E., Smith K.W., Butts D.R., Zamora L.F. Local excision of carcinoma of the rectum for cure. Surg. 1993;111:555–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda K., Maruta M., Sato H., Hanai T., Masumori K., Matsumoto M., Koide Y., Matuoka H., Katuno H. Outcomes of novel transanal operation for selected tumour in the rectum. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2004;199:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu Q., Petros J.G. Extraperitoneal rectal perforation due to retroflexion fibreoptic proctoscopy. Am. Surg. 1999;65:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez R.P., Phelan H., Hassan M., Ellis N., Rodning C.B. Is Faecal diversion necessary for non-destructive penetrating extraperitoneal injuries? J. Trauma. 2006;61:815–819. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000239497.96387.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvatore D., Jr., Diggs L., Crankshaw L., Lee Y., Vinces F. No evidence supporting the routine use of digital rectal examinations in trauma patients. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:265–269. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velmahos G.C., Gomez H., Falabella A., Demetriades D. Operative Management of Civilian Rectal Gunshot Wounds: simpler is better. World J. Surg. 2000;24:114–118. doi: 10.1007/s002689910021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trust M.D., Veith J., Brown C.V.R., Sharpe J.P., Musonza T., Holcomb J., Bui E., Bruns B., Hopper H.A., Truitt M., Burlew C., Schellenberg M., Sava J., Vanhorn J., Eastridge B., Cross A.M., Vasak R., Vercuysse G., Curtis E.E., Haan J., Coimbra R., Bohan P., Gale S., Bendix P.G., The AAST Contemporary Management of Rectal Injuries Study Group Traumatic Rectal Injuries: is the combination of computed tomography and rigid proctoscopy sufficient? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85:1033–1037. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]