Abstract

Different parasites cause severe lose in quantity and quality of crops. Many parasites develop haustorial cells and stylets that penetrate the host using secreted enzymes and mechanical pressure. Cysteine proteases are pre-pro-enzyme produced by parasites that are essential for normal parasitism. Papain is also a kind of cysteine proteases such that its propeptide segment has inhibitory properties and limits the protease activity of papain. To investigate the inhibitory effects of papain propeptide on some parasite proteases, we cloned inhibitory propeptide of papain of Ipomoea batatas, and enzymatic fragments of Diabrotica virgifera cathepsin L-like protease-1, Meloidogyne incognita cathepsin L-like protease 1, Heterodera glycines cysteine protease-1, Cuscuta chinesis cysteine protease and Orobanche cernua cysteine protease. After purification of recombinant inhibitory propeptide and enzymatic fragments, the inhibition activity of propeptide on cysteine proteases was measured. Finally inhibitory propeptide was transformed into tomato and transgenic plants resistance to parasites (bioassay) were examined. We demonstrated papain-propeptide inhibits cysteine protease of mentioned parasites. In transgenic tomato plants, papain-inhibitory propeptide effectively interrupted haustoria development. Haustoria-digitate cells of dodder could not differentiate and develop into the phloem and xylem hyphae on transgenic tomatoes. Parasites grown on transgenic tomatoes showed reduction in vigor and productivity due to defective connection of haustoria. Lower ratio of female nematodes and a decrease of nematode egg mass per transgenic line indicated biocontrol of nematode. The changes in growth factors of parasite challenged transgenic lines relative to controls, indicates the efficacy of papain propeptide in control of parasitism.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-019-00675-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cuscuta chinesis, Papain protease, Parasitism, Nematodes

Introduction

Products loss due to parasites are a great threat to food security and economy of farmers. Interactions of plants with parasites are diverse and in the parasitism, the degradation of non-self-proteins by both the parasite and plant plays a great function. Dodders (Cuscuta spp.) and Orobanchaceae family are an obligatory parasite that connects to the petiole or stem of host crops, causing severe losses in production efficiency (Albert et al. 2010; Ashigh and Marquez 2010). The yield reduction in crops such as tomato and alfalfa infested with parasitic plants can reach as high as 60% (Mishra 2009; Saric-Krsmanovic et al. 2015; Yoder and Scholes 2010). Parasite nematodes, such as Heterodeera glycines, Meloidogyne incognita and Globodera rostochiensis are obligate parasites that use a specialized spear called a stylet and have a unique and specialized way to infect their hosts. To assist their parasitism, they inject effector enzymes into host where nutrition sites will be organized. These enzymes change the vascular cell division rate, resulting in re-differentiation of cells, formation of great sized and metabolically active multinucleate cells called giant cells (Birschwilks et al. 2007). Nematode-enzyme effectors mainly consist of proteins (i.e. proteases, cellulases, etc.) and among them cysteine proteases are very important.

Parasites are very intricate pests to control and currently effective control in field is based on preventative and management strategies including avoiding parasite-infested soils, burning weed patches and applying non-selective pesticides and herbicides prior to seed emergence. These control procedures are laborious, expensive, and hazardous to the environment (Dennis 2013; Santamaria et al. 2015). Production of resistant transgenic lines is a promising strategy for reducing parasites damage.

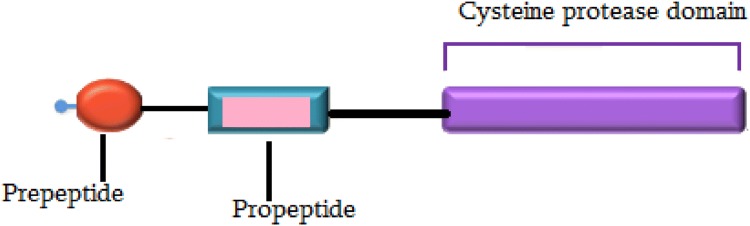

Plant parasitism begins with the developing haustorial cells (in the case of weed parasites and fungi) and stylet (in the case of nematodes) that penetrate the host tissues by secreting sticky substances and enzymes, and applying mechanical pressure (Vaughn 2002), which consequently lead to a physiological and physical bridge formation between the parasite and host (Sajid and McKerrow 2002). Most of parasites synthesise a protein with a cysteine protease activity essential to parasitism. Prepeptide subunit of cysteine proteases is a signal sequence that break up from the proenzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum (Okamoto et al. 2003), and a propeptide subunit that fold on active site and inhibits function of cysteine protease (Fig. 1). By removing the inhibitory-propeptide subunit from the enzyme, parasite-cysteine proteases convert to an active form. Parasite-cysteine proteases can weaken host structures through protein digestion and has a role in the successful parasitism (Bleischwitz et al. 2010).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the Ipomoea batatas cysteine protease subunits

In our field research, we observed that Ipomoea batatas, known as sweet potato, is more resistance to Cuscuta sp. and nematodes than Solanum tuberosum. Therefore, propeptide of cysteine protease of I. batata (ICP-1) was considered as potential inhibitor of parasite proteases including: Globodera rostochiensis cysteine protease-1 (GCP-1), Meloidogyne incognita cysteine protease-1 (MCP-1) Heterodera glycines cysteine protease-1 (HCP-1), Cuscuta chinesis cysteine protease-1 (CCP-1) and Orobanche aegyptiaca cysteine protease-1 (OCP-1).

This study was set to indicate the role of cysteine proteases in parasitism, and transform Solanum lycopersicum with the propeptide subunit of the ICP-1 through Agrobacterium tumefaciens method to enhance resistance to parasites.

Materials and methods

Cloning of inhibitory propeptide of the ICP-1

Total RNA was purified from 120 mg of leaf of I. batatas according to the Amini et al. (2017) method. First cDNA strand was synthesized (10 µg total RNA) using a 2-step RT-PCR kit consisting of a M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase and oligo-dT primers based on the manufacturer’s instructions. The propeptide fragment of the ICP gene (accession No.: FB701665), was amplified from I. batatas cDNA by means of a PCR with synthesized primers (Table S1) containing a 6 × His tag at the protein’s C-terminus and ligated to the T/A cloning vector.

Flanking Sst and Bam HI I restriction sites are underlined. The orientation and junctions of the resulting constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The propeptide segment was subcloned into the pET-21a and pBI121 binary vectors separately, which harbors the nptII sequence as a selectable marker (kanamycin resistance gene), and transformed via a freeze–thaw method into A. tumefaciens strain LBA4404 for tomato transformation (Amini et al. 2017).

Cloning of cysteine protease domain of the GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 and OCP-1

To study ICP-1 inhibitory propeptide capability on the mentioned parasite proteases, the enzymatic fragment of GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 and OCP-1 were amplified with synthesized primer-oligonucleotides (Table S1), ligated in pET-21a vector and the recombinant cysteine protease was expressed and purified from E. coli cell culture.

Protein assay

Purification of cloned segments of, GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1, OCP-1 and ICP-inhibitory propeptide

For purification of ICP- inhibitory propeptide, and cysteine protease domain of GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 and OCP-1, total protein was extracted from E. coli cells (Saify Nabiabad et al. 2011). Total proteins separately were loaded into the nickel affinity resin column by a linear flow rate of 50 cm h−1 at 4 °C, via peristaltic pump. After loading of total protein, the column was washed with resuspension buffer (250 mM NaCl, 4 M urea and 40 M Na-phosphate, adjusted to pH 7.5). Elution of his-tagged ICP- inhibitory propeptide, and mentioned cysteine protease domains from columns were performed by elution buffer (4 M urea, 300 mM NaCl, 50 M Na-phosphate, pH 7.5, and 150 mM Imidazole). The eluted proteins were collected, run on 9% nonreducing SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Purified proteins were stored at − 20 °C.

Determination of IC50 and inhibition kinetics of the ICP-inhibitory propeptide

The purified ICP-inhibitory propeptide was further evaluated by determining its IC50 (50% inhibition concentration) value. IC50 of inhibitory propeptide was determined as a function of the relative cysteine proteases activity (1.5 mg) at various concentrations of purified inhibitory segment (0.07–20 µg). Here, the papain substrate Cbz-Phe-Arg-pNA was used as a colorimetric substrate of cysteine proteases. Inhibitor propeptide in different concentrations was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min with 1.5 mg recombinant cysteine proteases and 8.27 μg dipeptide in 100 μL 0.1 M Na-citrate, pH 7.5. Para-nitroaniline absorbance was determined at 405 nm after addition of 100 μL 5 mM PMSF in DMSO.

Plant materials and transformation

Hypocotyls of tomato were cultured on MS medium culture containing BAP (1 mg/L) and IAA (0.1 mg/L) for 2 days. A. tumefacience LBA4404 strain harboring ICP propeptide-pBI121 plasmid was cultured in LB medium until the OD at 600 nm reached to 0.6. The A. tumefacience culture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and pellets were resuspended in MS liquid medium that contained acetosyringone (50 mg/L), kanamycin (50 mg/L) and rifampicin (100 mg/L). Hypocotyls were surface-sliced with a scalpel and co-cultured for 5 min in the bacterial suspension in triplicates followed by drying on sterile filter paper to remove bacterial solution, and cultured on solid MS medium containing 0.1 mg L−1 IAA and 2.5 mg L−1 BAP and incubated for 45 h at 26 ± 3 °C in the dark. After co-culture, the explants were washed by soaking in sterile distilled MS, blotted on filter paper, and were then transferred to co-culture medium supplemented with cefatoxim (200 mg/L) and kanamycin (100 mg/L) and cultured for 2 weeks under 50 µE m−2 s−1 at 25 ± 2 °C. Callus tissues with regenerating shoots were removed from the hypocotyls and transferred on shoot elongation medium (MS medium, 100 mg L−1 kanamycin, 1.0 mg L−1 BAP) to induce shoot elongation. When shoots developed to a height of 4 cm, plantlets were transferred to rooting-induction media (MS medium, 100 mg L−1 kanamycin, 0.1 mg L−1 IAA). Each rooted plantlet was transferred to a vase containing sterile sand and soil (1:1 v/v) to grow in standard greenhouse.

PCR and RT-PCR analysis of putative transgenic tomato lines

According to the method of Kim and Hamada (2005), genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of putative transgenic and non-transformed lines propagated in a greenhouse. Amplification using PCR was performed to detect specific DNA sequence using specific primers of the ICP-propeptide subunit. Amplification conditions for PCR reactions were as follows: one cycle at 94 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 58.5 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 25 min. PCR products were separated on agarose gels (1%), and the ethidium bromide-stained fragments were visualized with UV light.

For expression analysis of the ICP propeptide subunit, total RNA was purified from 100 mg of young shoots of non-transformed and putative transgenic lines by means of RNX-plus TM kit (Cinna Gen, Iran) and treated extensively with DNase I to remove any contaminating genomic DNA. cDNA was synthesized from 10 µg total RNA using 2-step RT-PCR kit (M-MuLV Reverse and an oligo-dT primer) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA (1–5 µL) was used as a template in PCR reactions to amplify the sequence of the ICP propeptide subunit using specific primers as described for genomic PCR analysis.

Dodder germination, cultivation, and synchronized infection

Dodder seeds were dipped in concentrated sulfuric acid for 15 min, washed with distilled water, and then treated for 10 min with sodium hypochlorite (1.5%). Seeds were rinsed three times for 2 min each with distilled water, followed by plating on moist filter paper in Petri dishes. Germinated seedlings of dodder were placed next to Coleus blumei plants under 8 h/15 h night/day light conditions at 25 °C and left to grow for 5 weeks (Amini et al. 2018). Coleus blumei tolerated the dodder infection and therefore presents more twines for use in synchronized infection. For infection of 28-day-old non-transgenic and transgenic tomato plants, C. chinesis shoot tips of about 15 cm lengths were wrapped around a wooden stick and after developing prehaustoria after 48 h, C. chinesis shoots were unwound from the stick and transferred to tomato plants and curled around the stem.

Effects of transgenic lines on C. chinesis vigor

The number of prehaustoria and haustoria per plant, total dodder mass, and total dodder seed numbers were determined as parameters of C. chinesis vigor. Flowering time of the dodder on non-transgenic and transgenic lines was documented. Seed samples separated from general dodder mass tissue by sieving and total seed per plants numbered and weighed. Transformed and wild type lines were challenged with C. chinesis, with four replications of each line. Each experiment had three technical independent replicates and data presented as means of technical replicates. Data analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance and student’s t test with SAS software (version 8.2).

Histological studies

For histological investigations, 10 days after parasitization, when the dodder grew vigorously, parasite growth behavior on tomato plants was assayed and several sample were prepared after every 2 h from 9:00 to 15:00 on the sampling day. The connection points of dodder on plants were cut off using a scalpel and fixed in FAA 70 (formalin-acetic acid–ethanol, 10:5:85, v/v) for 18 h, dehydrated in a graded series of alcohol and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections 8 µm thick were cut on a MICRODS 4055 microtome and after mounting on slides, deparaffinized in toluene. Slides was fixed and stained with eosin and hematoxylin, and finally stained slides were examined with the LABOMED light microscope.

Bioassay of transgenic lines expressing ICP-inhibitory propeptide against M. incognita

A pure culture of M. incognita was maintained on tomato plants in a glasshouse. Egg mass was collected from the contaminated roots of 50 days-old plants using forceps and incubated in a two layered paper in a Petridish containing sterile distilled water for hatching. Newly hatched second-stage juveniles (J2s) were used for all the experiments.

A 12 days old transgenic plants in growth chamber (16: 8 h light: dark photoperiod) were inoculated with hatched J2s (approximately 500 J2s) in the root area, incubated at 27 °C and 75% relative humidity in randomized complete block design with three replicates. Roots were harvested 30 days post-inoculation (DPI), and washed. Total number of females, galls, egg masses, eggs/egg mass and nematode multiplication factor [(number of eggs per egg mass × number of egg masses) ÷ nematode inoculums level] for each plant was recorded (Papolu et al. 2013; Dinh et al. 2014). Data were analyzed using One-Way ANOVA and CRD test followed by Duncan’s multiple-comparison test with significance level at P < 0.05 (SAS software, version9.3).

Results

Cloning, expression analysis and purification of proteases

Enzymatic fragment of GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 OCP-1 and ICP-inhibitory propeptide was amplified using specific primers (Fig. 1a). The ICP-inhibitory propeptide was cloned into T/A cloning vector and transformed to E. coli. The PCR cloning, blue/white screening, restriction enzyme digestion, and sequence analysis demonstrated that ICP-inhibitory propeptide was cloned properly (Table S2). The ICP-inhibitory propeptide was digested from T/A vector and sub-cloned into the pBI121 binary vector.

Enzymatic fragments of GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 and OCP-1 were cloned into the pET-21a. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that cloned segments are expressed (Fig. 2b). Results of SDS-PAGE showed purified recombinant segments have expected molecular weights (Fig. 2c). According to these findings, mentioned segments were properly cloned and purified for next analysis. Results of sequenced and nucleotide alignments confirmed that mentioned segments were cloned appropriately (Tables S2–S7).

Fig. 2.

From cloning to purification of enzymatic fragment of GCP-1, MCP-1, HCP-1, CCP-1 OCP-1 and ICP-inhibitory propeptide. Amplification of mentioned segments using specific primers and PCR (a). RT-PCR detection of ICP-inhibitory propeptide in transgenic plants in the left of ladder 100 bp (M), c is negative control; WT is tomato wild type; M1, M3 and M5 are tomato transgenic lines. In the right of ladder are enzymatic segments expressed in pET vector (b). The purified ICP-inhibitory propeptide and mentioned enzymatic fragments on SDS-PAGE. ICP-i is ICP-inhibitory propeptide; M is protein ladder; and other wells are mentioned enzymatic fragments

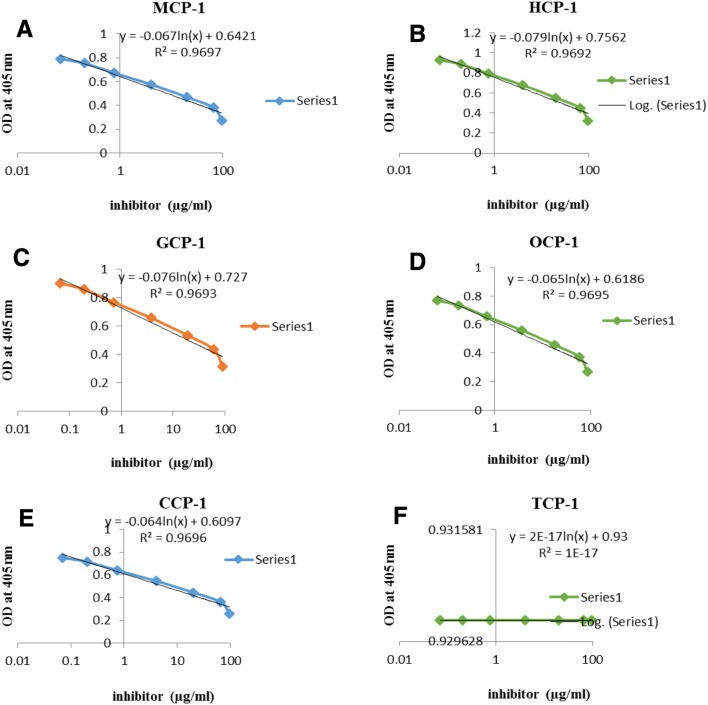

Inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ICP-inhibitory propeptide

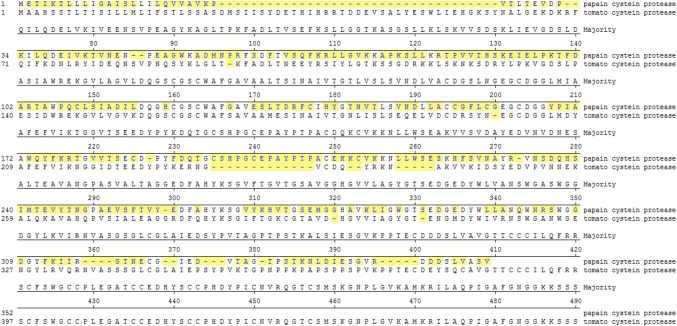

The inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the purified ICP-inhibitory propeptide was evaluated by the colorimetric substrate Cbz-Phe-Arg-pNA. Analysis of inhibition kinetics demonstrated that IC50 values of ICP-inhibitory propeptide on CCP-1, OCP-1, MCP-1, GCP-1 and HCP-1 was 5.5, 6.15, 8.3, 19.8 and 25.55 µg/mL, respectively (Fig. 3). Results of the IC50 assay showed that by incubating the ICP-inhibitory propeptide with the parasitic cysteine proteases, enzymatic activity of the parasite proteases decreased. According to these data, the propeptide binds to the active site of cysteine proteases and inhibited their enzymatic activity, thereby expressing the ICP-inhibitory propeptide in plants that can disrupt parasite penetration into plant tissue. To investigate ICP-inhibitory propeptide inhibition on tomato cysteine protease known as TCP-1, the enzymatic fragment of TCP-1 was produced and purified as recombinant protein from transformed E. coli. Inhibitory assay of purified TCP-1 was done and data showed that the TCP-1 protease activity was not influenced by the ICP- inhibitory propeptide (Fig. 3f). Therefore, transformed ICP-inhibitory propeptide has no negative effect on transgenic host. To describe this difference, the amino acid sequence of ICP and TCP-1 was aligned using the MegAlign software. Based on the alignment results, the propeptide of ICP-1 has an extension of amino acids in its C-terminal and N-terminal relative to the TCP-1 propeptide. These extension amino acid sequences seem to avoid the interaction between the TCP-1 peptidase and the ICP-inhibitor propeptide. Moreover, the different amino acid sequence of the catalytic segments prevents autotoxicity of the transgene product (Figs. 4). The catalytic site of TCP-1 protease are Cysteine and Histidine, forming a catalytic dyad and other amino acid residues that play an important role in catalysis are Glutamine 156 and Asparagine 319. Glutamine 157 precede the catalytic Cysteine 163 and help in the formation of the oxyanion hole. Asparagine 318 orients the imidazolium ring of the catalytic Histidine 298.

Fig. 3.

Evaluating inhibitory properties of the ICP-inhibitory propeptide using the colorimetric substrate Cbz-Phe-Arg-pNA. The inhibitory activity was determined in the presence of various concentrations of the ICP-inhibitory propeptide at 1.5 mg/mL of mentioned parasites-cysteine proteases (CCP-1, OCP-1, MCP-1, GCP-1 and HCP-1; panel a–e) and 8.0 μg colorimetric substrate according to manufacturers’ instruments. Panel f is a Plot for inhibitory assay of ICP-inhibitory propeptide on TCP-1 (tomato-cysteine protease)

Fig. 4.

Alignment of the protein sequence of the ICP-1 with TCP-1 using the MegAlign software. Yellow shaded amino acids are different in the two sequences

As seen in the Fig. 3 the ICP-inhibitory propeptide has the highest inhibitory on the MCP-1 (among nematodes) and CCP-1 (between parasitic plants), therefore M. incognita and C. chinesis were used as the candidate parasites to analyze resistance of transgenic tomato lines.

Generation of tomato transgenic plants

Hypocotyls of tomato were transformed by A. tumefacience, transgenic lines selected on the selection medium containing kanamycin, and finally each rooted plantlet was transferred to a vase containing sterile sand and soil (1:1 v/v) to grown in standard greenhouse. The results of PCR demonstrated that compared to non-transgenic lines, the ICP-inhibitory propeptide was transferred to transgenic lines and RT-PCR results indicated that the mentioned segment is expressed in transgenic lines (Fig. 2).

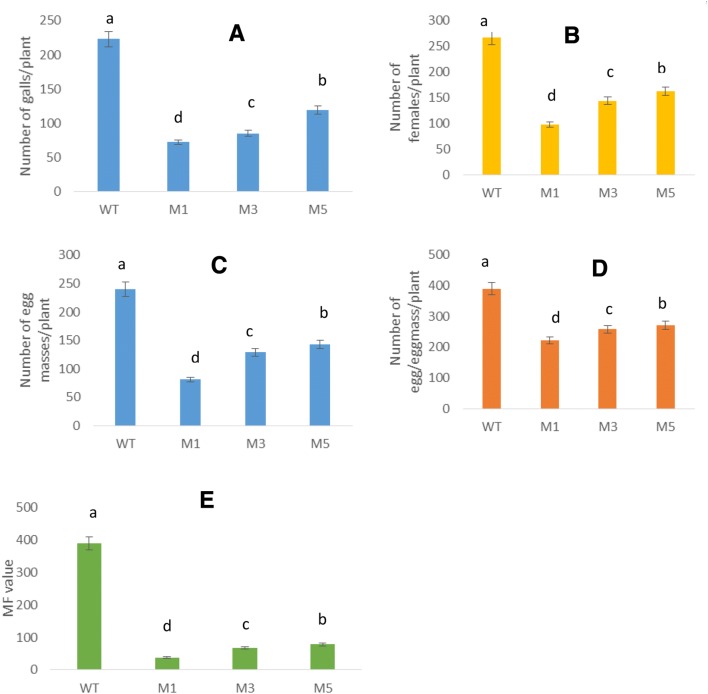

Evaluation resistance of transgenic lines against M. incognita

The recombinant ICP-inhibitory propeptide has a high inhibitory effect on nematodes-cysteine protease (especially on M. incognita; 8.3 µg/mL). To assess resistance of transgenic tomatoes against M. incognita, three T1 tomato lines (M1, M3, and M5) harboring the ICP-inhibitory propeptide were inoculated with M. incognita J2s. Compared to control lines, transgenic plants have no obvious phenotypical variation. At 30 DPI, the average number of galls/plant was reduced significantly (P < 0.05) by 46.6–67.7% in transgenic lines compared to the wild type (Fig. 5). In addition, the number of galls, females, egg masses, egg/egg masses and the multiplication factor (MF) was reduced significantly (P < 0.05) by 38.9–63.2%, 40.41–66.25, 30.25–43.07 and 80–90.25%, respectively (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5.

Resistance of transgenic lines harboring ICP-inhibitory propeptide against M. incognita. a galls number/plant, b number of females/plant, c number of egg masses/plant, d number of eggs/egg mass and the respective multiplication factor (MF) of M. incognitae in wild type plants (WT) and transgenic lines (M1, M3, and M5). Different letters on bars denote a significant difference at P < 0.05, CRD test

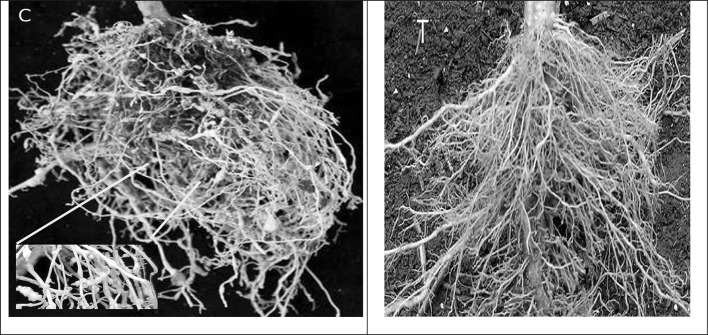

Fig. 6.

Comparision of nematode damage on control tomato (C) and transgenic line

ICP-inhibitory propeptide in transgenic tomato lines alters C. chinesis development

As indicated in the Fig. 3e, the recombinant ICP-inhibitory propeptide has a high inhibitory effect on dodder cysteine protease (CCP-1). To investigate the inhibitory effects of ICP-inhibitory propeptide on dodder invasion in transgenic lines, mature C. chinesis shoot tips of about 10 cm were used for the infection of transgenic and non-transgenic tomato seedlings (4-week-old). 48 h after infection, sticky discs were organized and haustorial protuberances tried to penetrate the host stem, but no further penetration or parasitism occurred following the haustorium stages on the transgenic tomato lines.

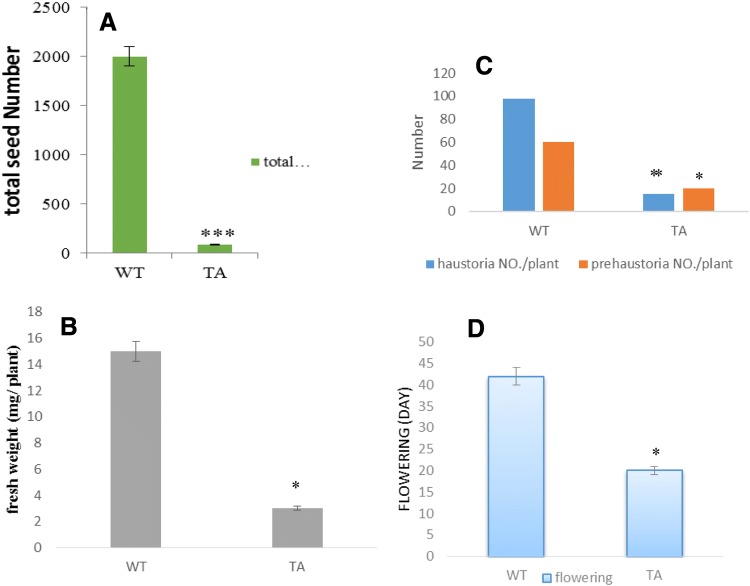

Total seed number was reduced in dodder plants grown on transgenic lines (Fig. 7a). The number of haustoria and prehaustoria attached to the host plants were calculated. Transgenic lines had 15.2 (± 1.8) haustoria/plant, but non-transgenic plants developed on average 99 (± 1) hauostoria/plant (Fig. 6c). Compared to biomass on non-transgenic lines (15.8 g/plant), in transgenic lines dodder biomass reduced by about 81.6% (2.9 g/plant) (Fig. 7b). In addition, dodder grown on transgenic lines showed more than 2 times higher auto-parasitism than parasites on non-transgenic hosts (data not presented). In auto-parasitism, interconnections of parasite stem of the same plant through haustorial connection between themselves reduce the transportation distances within the same plant. Flowering time in dodder grown on transgenic lines reduced (Fig. 7d), as early flowering in parasite plants is one of the ways to escape stress.

Fig. 7.

Comparision of dodder biological growth index in 20-day growth on transgenic and non-transgenic tomato lines. Dodder total seed number (a), dodder biomass (b), and number of prehaustoria and haustoria (c) on transgenic tomato lines (TA) was significantly reduced than wild type (WT) plants. d To escapes stress, dodder plants that completes its life cycle on transgenic lines plants flowered earlier than those on non-transgenic lines. Data are means ± 1SD of three replicates per treatment. Significant differences between transgenic lines and wild type were evaluated using Student’s t-test (* < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001)

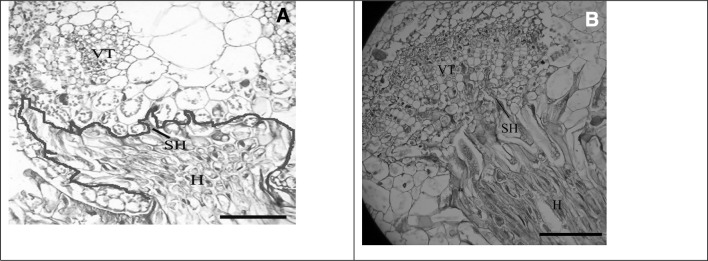

The role of CCP-1 in haustoria development, and inhibitory activity of ICP-inhibitory propeptide in transgenic tomato lines against dodder were annotated using histological studies. Histological results demonstrated that in the investigated samples (90%), although haustorial protuberance structures penetrated into the transgenic plant stem, but the haustoria tips were not developed and searching hypha was not differentiated into the phloem or xylem hyphae (Fig. 8). Therefore, there was no significant connection or parasitism between dodder and transgenic lines.

Fig. 8.

Histological studies of the connection sites of C. chinesis on tomato lines using light microscope (LABOMED) equipped with a camera. a Transversal sector of a tomato stem expressing propeptide with an attached C. chinesis strand. The tips of dodder haustoria was not developed in the host and searching hypha (blue line) was not differentiated and developed into the phloem or xylem hyphae in transgenic lines. b Transversal sector of a non-transgenic plant, searching hyphae have connected to vascular tissue of the host. Searching Hyphae: SH; Vascular Tissue: VT; haustoria: H. Scale bars are 100 µm

Discussion

The success of parasitism mainly depends on the utilization of effector enzymes to circumvent the host immune responses and to digest the host vascular tissue. This study was devised to investigate inhibitory effect of ICP-inhibitory propeptide on cysteine protease in some plant parasites and transgenic assay against parasites. According to the previous studies, stable transformation of important crops to enhance resistance against parasites has been accomplished in some crops (Papolu et al. 2013; Dinh et al. 2014). The targeted parasite genes in some of the reports are conserved in other organisms and animals, and because of their possible non-target effects, the transgenic plants may demonstrate to be ineligible for field trial. Cysteine proteases especially cathepsin L are attractive candidate genes for silencing, not only because these enzymes are decisive for parasitism, but they lack significant homology to enzymes in other organisms.

Cysteine proteases play basic roles in the biology of parasites-host and act in the parasitic attack (Sajid and McKerrow 2002). These types of proteases are effective in the degradation of PR proteins and have specialized processing functions that are very important in cell signaling (Borsics and Lados 2002). In the previous researches, we showed that the processes of parasitism and the formation of haustoria in parasite involve the activation of parasite cysteine protease in the host (Amini et al. 2018). Also, there are some evidence that Cathepsin-like proteases have antiparasitic activity. Therefore, recombinant ICP-inhibitory propeptide had been purified from I. batatas (Sweet potato), expressed as inactive pre-proenzyme and was assayed for its ability to inhibit the parasite cysteine proteases. This study provided great insight into the association of dodder-cysteine protease in the searching hyphae organization and development. Digitate cell structures of haustoria produce and develop specific searching hyphae, long penetrating cells that grow toward the host vascular system for nutrition (Amini et al. 2017; Dinh et al. 2014).

Compared to non-transgenic plants, haustoria contaminated transgenic lines showed imperfection in searching hyphae and these structures were not expanded, no functional haustoria were organised due to expression of ICP-inhibitory propeptide in the transgenic lines after prehaustoria contact. Digitate cells that have an obvious stained cytoplasm and large nuclei may be effective in the production and secretion of the CCP-1 as the searching hyphae develop and elongate into host vascular tissue.

Transgenic bioassay results appropriately indicated that the ICP-inhibitory propeptide acts as an inhibitor of the main parasite-cysteine proteases and these results are in agreement with previous reports (Bleischwitz et al. 2010), which showed that spray of propeptide on tobacco plants contaminated with dodder inhibits the parasite.

The results also indicate that transgenic tomato lines expressing the ICP-inhibitory propeptide are less susceptible to parasites. Therefore, ICP-inhibitory propeptide has a potential function as defense peptide against plant parasites and surprisingly has no inhibitory activity on the TPC-1 (host protease). The ICP-inhibitory propeptide covers the binding site of the cysteine protease of parasite and interjects a hindrance between the catalytic center and substrate (Amini et al. 2018).

As observed in Fig. 5, there is significant difference among tomato transgenic lines harboring ICP-inhibitory propeptide (M1, M3 and M5) against M. incognita. The main reasons for this difference maybe because of the difference in copy number of transferred fragment of ICP-inhibitory propeptide to transgenic lines. Also, the chromosomal position of transferred segment may affect gene expression so that in the transgenic lines with the higher résistance, the transferred segment were located in the regions of chromosome (near to enhancers) that are more active. Moreover, uncontrolled environmental factors may have changed the gene expression and resistance evidence of the transgenic lines.

There are some reports about the possible use of protease inhibitors for resistance to pathogens (Ejeta et al. 1991; Wilhite et al. 2000; Borsics and Lados 2002) and it was demonstrated that expression of cysteine protease propeptide in transgenic crops can control weevil in alfalfa (Furuhashi et al. 2011; Marra et al. 2009) and mite pests in A. thaliana (Vaughn 2002).

As final conclusion, permanent expression of ICP-inhibitory propeptide in transgenic tomato lines was more effective than the spray of a propeptide suspension12 against parasites. Though, improving the site specific and expression levels of this inhibitor propeptide can provides complete control of the parasites. This study suggests a genetically modified strategy to control crop pest and parasites by using a novel endogenous inhibitory propeptide.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The research is partially supported by the Bu Ali Sina University.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haidar Saify Nabiabad, Email: homan_saify@yahoo.com.

Massoume Amini, Email: m.amini@basu.ac.ir.

Farzad Kianersi, Email: f.kianersi@agr.basu.ac.ir.

References

- Albert M, Kaiser B, van der Krol S, Kaldenhoff R. Calcium signaling during the plant-plant interaction of parasitic Cuscuta reflexa with its hosts. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;59:1144–1146. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.9.12675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini M, Saify Nabiabad H, Deljou A. Host-synthesized cysteine protease-specific inhibitor disrupts Cuscuta campestris parasitism in tomato. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2017;11:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s11816-017-0451-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amini M, Saify Nabiabad H, Deljou A. The role of cuscutain-propeptide inhibitor in haustoria parasitism and enhanced resistance to dodder in transgenic alfalfa expressing this propeptide. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2018;58:144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ashigh J, Marquez E (2010) Dodder (Cuscuta spp.) biology and management. NM State University, Guide A-615. vol 54. pp 31–34

- Birschwilks M, Sauer N, Scheel D, Neumann S. Arabidopsis thaliana is a susceptible host plant for the holoparasite Cuscuta spec. Planta. 2007;226:1231–1241. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleischwitz M, Albert M, Fuchsbauer HL, Kaldenhoff R. Significance of cuscutain, a cysteine protease from Cuscuta reflexa, in host-parasite interactions. PMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsics T, Lados M. Dodder infection induces the expression of a pathogenesis-related gene of the family PR-10 in alfalfa. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:1831–1832. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C (2013) Alfalfa management guide for Ningxia. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, pp 1–2. Retrieved 3 August 2013

- Dinh PTY, Zhang L, Brown CR, Elling AA. Plant- mediated RNA interference of effector gene Mc16D10L confers resistance against Meloidogyne chitwoodi in diverse genetic backgrounds of potato and reduces pathogenicity of nematode offspring. Nematology. 2014;16:669–682. doi: 10.1163/15685411-00002796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ejeta G, Butler LG, Hess DE, Vogler RK (1991) Genetic and breeding strategies for Striga resistance in sorghum. In: Ransom JK, Musselman LJ, Worsham AD, Parker C (eds) Proceedings of the 5th international symposium of parasitic weeds, CIMMYT, Nairobi, Kenya, 1991, pp 539–544

- Furuhashi T, Furuhashi K, Weckwerth W. The parasitic mechanism of the holostemparasitic plant Cuscuta. J Plant Interact. 2011;6:207–219. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2010.541945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hamada T. Rapid and reliable method of extracting DNA and RNA from sweetpotato, Ipomoea batatas (L). Lam. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1841–1845. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3891-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra B, Souza D, Aguiar J, Firmino A, et al. Protective effects of a cysteine proteinase propeptide expressed in transgenic soybean roots. Peptides. 2009;30:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra JS. Biology and management of Cuscuta species. Indian J Weed Sci. 2009;41:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Shimada T, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M, Minamikawa T. C-terminal KDEL sequence of a KDEL-tailed cysteine-proteinase (sulfhydryl-endopeptidase) is involved in formation of KDEL vesicle in efficient vacuolar transport of sulfhydryl-endopeptidase. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1892–1900. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papolu PK, Gantasala NP, Kamaraju D, Banakar P, Sreevathsa R, Rao U. Utility of host delivered RNAi of two FMRF amide like peptides, flp-14 and flp-18, for the management of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saify Nabiabad H, Yaghoobi M, Jalali-Javaran M, Hosseinkhani S. Expression analysis and purification of human recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator (rtPA) from transgenic tobacco plants. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;41:175–186. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2011.547371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajid M, McKerrow JH. Cysteine proteases of parasitic organisms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;120:1–21. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria M, Arnaiz A, Mendoza M, Martinez M, Diaz I. Inhibitory properties of cysteine protease pro-peptides from barley confer resistance to spider mite feeding. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saric-Krsmanovic M, Bozic D, Malidza G, Radivojevic L, et al. Chemical control of field dodder in alfalfa. Pestic Phytomedicine. 2015;30:107–114. doi: 10.2298/PIF1502107S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn KC. Attachment of the parasitic weed dodder to the host. Protoplasma. 2002;219:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s007090200024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhite E, Elden TC, Brzin J, Smigocki AC. Inhibition of cysteine and aspartyl proteinases in the alfalfa weevil mid gut with biochemical and plant-derived proteinase inhibitors. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JI, Scholes JD. Host plant resistance to parasitic weeds; recent progress and bottlenecks. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.