Exposure–response analyses based on pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) offer great promise in research and development for vaccination and immunotherapy. While clinical and systems pharmacology integrate actionable multiscale information, quantitative immunology has focused on structural models of immune responses without data‐based calibration or prediction. Given the growing immune data sets and to facilitate a systems approach to immunomodulation, we propose a paradigm shift in which the immune response, rather than the PK, captures “exposure.”

Clinical Pharmacology Principles for Immunomodulation

Immunomodulation differs from other pharmacological interventions. First, it is characterized by the delayed emergence of immune responses caused by, e.g., the slow maturation of antibodies following vaccination or the emergence of T‐cell responses after immune checkpoint inhibition. Although biological delays are not unique to immunotherapy and have been well characterized by the traditional pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic (PK‐PD) paradigm, additional value lies in understanding the specific mechanisms by which an immunomodulator activates (or inhibits) the immune system, which do not only relate to target turnover or physical drug distribution. Second, the immunomodulatory response is persistent, often lasting much longer than the original intervention because of memory cells that preserve information arising from the antigenic challenge or immune checkpoint inhibition enabling the activation of exhausted T cells. Lastly, these responses can functionally differ between (apparently) similar interventions, such as when modestly different vaccination doses or schedules give rise to profoundly different humoral immune responses or tumor‐infiltrating leukocytes lose function as a result of unfavorable microenvironment signals.

Therapeutic approaches directed at modulating immune responses do not easily fit in customary clinical pharmacology paradigms. Stroh et al.1 first emphasized the need for mechanistic models (conceptual and computational) to interpret efficacy data in immune‐competent, nonclinical model systems. Second, strong synergy between modeling and simulation and program acceleration is needed. Third is the recommended phase II/phase III dose: for any therapeutic, optimizing dose, infusion duration and schedule requires understanding dose–exposure–response relationships. Lastly, effective model‐informed drug development requires realistic models that go beyond empirical delays and explicitly represent effector immune system components.

The need to reframe dose–exposure–response paradigms for immunomodulatory interventions

One of the defining characteristics of immunomodulatory therapeutics is that the PD effect on disease is not directly because of administered therapeutics but because of immune response mediators that are modulated following a dosing event. This has been recognized by others: in inflammation,2 indirect drug effects are on immune cell responses, immune cells “mediate” inflammation, and the causal cascade goes from PK (drug exposure) on to PD (effect on mediators) and then to response against a certain disease (i.e., prevention of tissue damage).

Traditional PK‐PD constructs do not straightforwardly apply to immunomodulation. For example, in therapeutic vaccination there is no “dose” that directly relates to response as the half‐life of vaccines is relatively short and is not predictive of the resulting long‐lived immune response. Hence, “exposure” as the mediator of effect needs to be defined: does it relate to the therapeutic agent (e.g., vaccine or immune checkpoint inhibitor) or the effectors (e.g., the secreted immunoglobulins following vaccination or the increase in activated T cells postcheckpoint inhibitor treatment), which are slow to emerge and mature and somewhat distant from the dosing event(s)? As proposed to improve the probability of demonstrating an efficacy benefit, the framework of the “3 pillars of survival,”3 which include exposure at the target site of action (pillar 1), binding to the pharmacological target (pillar 2), and expression of pharmacological activity (pillar 3), is ill suited for immunotherapy. For reasons we have already mentioned, the separation between pillars 2 and 3 can be profound.

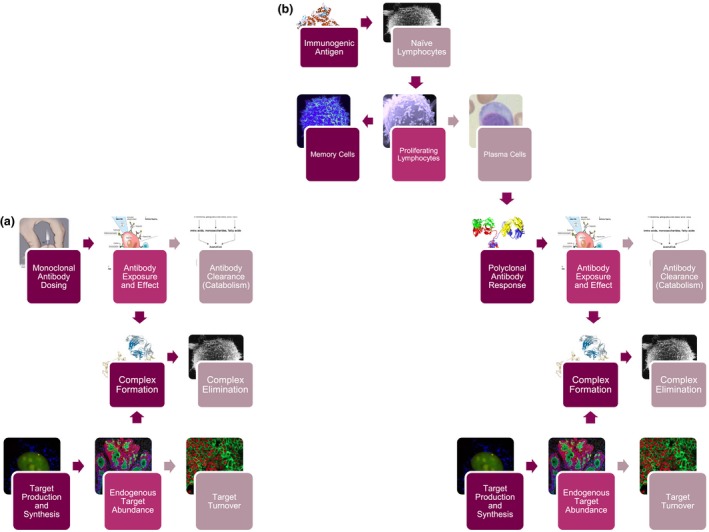

Adding to this already complex picture, immune response markers are not necessarily reflective of PD: strong immune responses can arise that yield poor or no efficacy. The experience with CYT006‐AngQB (Cytos Biotechnology, Schlieren, Switzerland), a therapeutic vaccine against angiotensin II studied for the treatment of high blood pressure, demonstrates the importance of vaccination schedule and quality of raised immune response. In an initial phase II study,4 CYT006‐AngQB was dosed at 300 and 100 μg at weeks 0, 4, and 12, providing antibody titers that resulted in ambulatory blood pressure lowering at the higher dose. To increase titers, in a subsequent study, the vaccine was given at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, and 10. However, this new schedule, although providing high titers, failed to produce a blood pressure effect. This is likely because of the more frequent vaccine schedule eliciting immunoglobulins with decreased affinities.5 The antibody response observed after vaccination is usually polyclonal, i.e., displays a broad spectrum of dissociation constants and concentrations as was recognized in the early days of immune response modeling.6 Assessment via titers (e.g., using Enzyme‐Linked ImmunoSorbent Assays), which represent the highest dilution at which an effect is observed, masks the relationship between immunoglobulin concentrations and affinities, with the titers being a mix of both. In other words, a high titer may not correspond to antibodies with the desired affinity, and higher or more frequent vaccine doses do not consistently yield an increase in the quality of the immune response. This of course differs from passive immunotherapy, in which a monoclonal antibody is manufactured to have a single affinity constant (Figure 1 a). Postvaccination antibodies are instead polyclonal, show a range of immune responses, and are “produced” inside the body (Figure 1 b), with the vaccine essentially providing “manufacturing instructions” to the host's B cells. A quantitative pharmacology model that would account for the observed differences in the CYT006‐AngQB response would likely have to incorporate affinity maturation and note how affinity maturation of the polyclonal response is influenced by dosing schedule for the specific construct under consideration. It would be difficult to predict the behavior of the two schedules based on typical PK‐PD approaches because a higher level of mechanistic detail is required. This kind of complexity extends to both humoral and cellular responses and points to the realization that raised immune responses are more akin to PK (exposure) than PD.

Figure 1.

- Monoclonal antibody response: image from National Institutes of Health Medical Arts, https://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/patient_education/pepubs/subq.pdf (public domain).

- Antibody exposure and effect: image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monoclonal_antibodies.svg (public domain).

- Antibody clearance (catabolism): image from TimVickers, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catabolism.svg (public domain).

- Complex formation: image from Fvasconcellos, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trastuzumab_Fab-HER2_complex_1N8Z.png (public domain).

- Complex elimination and naïve lymphocytes: image from Dr Timothy Triche, National Cancer Institute, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=1758 (public domain).

- Target Production and Synthesis: Image from Dan Larson, Antoine Coulon, Matt Ferguson, National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9922 (public domain).

- Endogenous target abundance: image from Markus Schober and Elaine Fuchs, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9852 (public domain).

- Target turnover: image from Urbain Weyemi, Christophe E. Redon, William M. Bonner, National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9867 (public domain).

- Immunogenic antigen: image from Jawahar Swaminathan and Macromolecular Structure Database staff at the European Bioinformatics Institute (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PDB_1sfr_EBI.jpg (public domain).

- Memory cells: image from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, https://www.flickr.com/photos/niaid/5950870236/ (licensed under CC BY 2.0).

- Proliferating lymphocytes: image from Dr Triche, National Cancer Institute, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=1944 (public domain).

- Plasma cells: image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plasmacell.jpg (public domain).

- Polyclonal antibody response: image from Tim Vickers, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antibody_IgG2.png (public domain).

- Target production and synthesis: image from Dan Larson, Antoine Coulon, Matt Ferguson, National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9922 (public domain).

- Endogenous target abundance: image from Markus Schober and Elaine Fuchs, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=9852 (public domain).

These considerations lead to a proposal to reframe the dose–exposure–response framework for the study of immunomodulatory interventions (Figure S1 ). We propose to consider, as the equivalent to exposure, the temporal profile and characteristics of mediators (immune cells or antibodies) elicited by the immunomodulator, as opposed to drug concentration or summary PK parameters (peak concentration, area under the curve, etc.). The equivalent of dose would be the immunomodulator dosing time or concentration‐time course at the site of drug action, as opposed to the customary amount of drug administered, infusion rate, dosing schedule. The equivalent of response would not change and remain a suitable biomarker proximal or distal to, but always correlated with, patient response (e.g., blood pressure in the CYT006‐AngQB example). By shifting the emphasis on the raised immune response, we focus our attention on the true mediators of PD and avoid the potential confusion generated by exclusively optimizing humoral and cellular responses as opposed to biomarkers representative of the desired effect. Examples of this shift are presented in Table 1 to further clarify our thinking.

Table 1.

Specific examples of immune responses and biomarkers in various immunotherapy contexts

| Category and example class of drug | Immune response mediator | Accessible biomarker distal to patient response | Accessible biomarker proximal to patient response |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vaccination Influenza vaccine |

Neutralizing antibody titer and memory T cells/naive B cells | Circulating antiflu MP/HA/NA antibodies Matrix Protein, Hemagglutinin, Neuraminidase | Protection/immunity to infection |

|

Suppression Anti‐TNF Tumor Necrosis Factor |

TNF (cytokine) | Reduction in free (non–drug bound) TNF levels | Disease scores—ACR American College of Rheumatology (arthritis) or PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (psoriasis) |

|

Suppression Peptide immunotherapy |

Dendritic cells/T cells | Expansion of tolerogenic T cells, loss of ex vivo responsiveness to antigen | Reduction in effector T cells or cytokine release following challenge |

|

Activation Anti‐PD‐1 Programmed Death‐1 |

Activated, tumor‐specific T cells | Circulating cytotoxic T‐cell activation and proliferation | Antigen‐specific tumor infiltrating lymphocytes |

This reframing has implications for bioanalytical sciences. Simply written, the discipline of clinical pharmacology needs to pursue quantification of immune response correlates with the same vigor as it has pursued quantification of drug exposure. In the case of the humoral (immunoglobulin) immune responses, these correlates include production of antibody by plasma cells and their affinity ranges and kinetics (ideally, concentrations rather than titer). The monitoring and optimization of affinity maturation would prevent the emergence of ineffective responses and would allow discrimination among dosing schedules. In other words, assays need to be designed to properly quantify the immune system components that are specific to the target antigen. For the cellular immune response, methods to monitor it ex vivo (both peripheral and tissue) are readily available, e.g., Enzyme‐Linked ImmunoSPOT assays and flow cytometry. However, it is of paramount importance to monitor antigen‐specific cellular responses relevant to the intended indication because these are more likely to represent a true PD effect, i.e., one coupled with improved clinical efficacy. This was demonstrated in a study of non‐small cell lung cancer patients that correlated tumor antigen burden and subsequent prevalence of tumor antigen‐specific T cells with durable responses to immune checkpoint blockade.7 Cell migration and tissue infiltration would also be important to quantify (the equivalent of systemic and site of action exposures in the traditional setting), and novel image analysis strategies could be used to better characterize in situ immune correlates.8

PK‐PD modeling and simulation, currently a mainstay of clinical pharmacology, can contribute to the optimization of immunomodulation. Parsimonious PK‐PD approaches account for minimally required features of the immune response: timing (schedule) of immunotherapy administration and the resultant time course of immune response mediator(s), partitioning of the target population between responders and nonresponders (by mixture statistical models), and counterregulatory response (resistance or immune regulation, e.g., by regulatory T cells). PK‐PD can substantially benefit from more realistic systems pharmacology approaches9, 10 that elucidate the mechanism, timing, and extent of emerging immune responses depending on the questions posed by the drug discovery and development team.

Ultimately, these considerations can have an impact on experimental and trial design and perhaps on drug approval and clinical practice. We do not intend to provide guidance for how to capture this framework in a drug label, although we can certainly anticipate an evolution in immunotherapy toward a more personalized approach that could well require additional descriptors of the immune response in the label. There is likely value in some real‐time monitoring to adjust dosing (level and/or frequency) to enable a successful outcome for patients. Specific parameters and how to monitor them will depend on each drug. Such companion “diagnostics” may not be cheap to develop and implement and would only be viable if they brought added value to patient survival and quality of life. Personalized medicine is certainly on the horizon, and we believe that the paradigm shift proposed here will accelerate our understanding of how to implement personalized medicine strategies for immunomodulatory drugs.

Immunology is often an empirical science. Immunomodulatory approaches can bring effective and durable interventions: the challenge of what to measure and when is compounded by the complexity of raised immune responses. We suggested here a reframing of dose–exposure–response science for immunomodulation. Our purpose is to frame the question as clearly as possible, and it is our hope that this reframing will improve communication between clinical pharmacologists and experimental immunologists and suggest both avenues for data collection and ideas for experimental design.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Conflict of Interest

P.V. is on the Editorial Advisory Board of the Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics and was an Associate Editor of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics: Pharmacometrics & Systems Pharmacology. All other authors declare no competing interests for this work.

Supporting information

Figure S1. A view of the traditional dose‐exposure‐response paradigm is compared with modifications required to accommodate the unique features of immunomodulation.

Acknowledgments

Some of the ideas outlined in this perspective were partially presented at the Sixth International Symposium on Measurement and Kinetics of In Vivo Drug Effects, NH Leeuwenhorst—Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands, April 21–24, 2010, at the Sixth American Conference on Pharmacometrics, Crystal City, VA, October 3–7, 2015, and the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists on Immuno‐Oncology Modeling—From Molecular Biology to Clinical Efficacy, San Diego, CA, November 12, 2017. The authors acknowledge the helpful input over time into this perspective from numerous colleagues as well as the comments of the anonymous referees.

References

- 1. Stroh, M. et al Challenges and opportunities for quantitative clinical pharmacology in cancer immunotherapy: something old, something new, something borrowed, and something blue. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 4, 495–497 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lon, H.K. , Liu, D. & Jusko, W.J. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling in inflammation. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 40, 295–312 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morgan, P. et al Can the flow of medicines be improved? Fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacological principles toward improving phase II survival. Drug Discov Today 17, 419–424 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tissot, A.C. et al Effect of immunisation against angiotensin II with CYT006‐AngQb on ambulatory blood pressure: a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase IIa study. Lancet 371, 821–827 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cytos biotechnology reports biochemical findings from phase IIa study with hypertension vaccine CYT006‐AngQb. <www.kurosbiosciences.com/uploads/news/id135/Cytos_Press_E_090624.pdf>.

- 6. Bell, G.I. Mathematical model of clonal selection and antibody production. Nature 228, 739–744 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGranahan, N. et al Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351, 1463–1469 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yigitsoy, M. et al The importance of co‐localized resting CD8 + T cells and proliferating tumor cells in gastric cancer. Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, April 1–5, 2017. Abstract 3958.

- 9. Palsson, S. et al The development of a fully‐integrated immune response model (FIRM) simulator of the immune response through integration of multiple subset models. BMC Syst. Biol. 7, 95 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen, X. , Hickling, T.P. & Vicini, P. A mechanistic, multiscale mathematical model of immunogenicity for therapeutic proteins: part 1‐theoretical model. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 3, e133 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. A view of the traditional dose‐exposure‐response paradigm is compared with modifications required to accommodate the unique features of immunomodulation.