Abstract

Background

Financial hardship among survivors of pediatric cancer has been understudied. We investigated determinants and consequences of financial hardship among adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Methods

Financial hardship, determinants, and consequences were examined in 2811 long-term survivors (mean age at evaluation = 31.8 years, years postdiagnosis = 23.6) through the baseline survey and clinical evaluation. Financial hardship was measured by material, psychological, and coping/behavioral domains. Outcomes included health and life insurance affordability, retirement planning, symptoms, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Odds ratios (ORs) estimated associations of determinants with financial hardship. Odds ratios and regression coefficients estimated associations of hardship with symptom prevalence and HRQOL, respectively. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Among participants, 22.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 20.8% to 24.0%), 51.1% (95% CI = 49.2% to 52.9%), and 33.0% (95% CI = 31.1% to 34.6%) reported material, psychological, and coping/behavioral hardship, respectively. Risk factors across hardship domains included annual household income of $39 999 or less vs $80 000 or more (material OR = 3.04, 95% CI = 2.08 to 4.46, psychological OR = 3.64, 95% CI = 2.76 to 4.80, and coping/behavioral OR = 4.95, 95% CI = 3.57 to 6.86) and below high school attainment vs college graduate or above (material OR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.45 to 3.42, psychological OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.18 to 2.62, and coping/behavioral OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.38 to 3.06). Myocardial infarction, peripheral neuropathy, subsequent neoplasm, seizure, stroke, reproductive disorders, amputation, and upper gastrointestinal disease were associated with higher material hardship (all P < .05). Hardship across three domains was associated with somatization, anxiety and depression (all P < .001), suicidal ideation (all P < .05), and difficulty in retirement planning (all P < .001). Survivors with hardship had statistically significantly lower HRQOL (all P < .001), sensation abnormality (all P < .001), and pulmonary (all P < .05) and cardiac (all P < .05) symptoms.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of adult survivors of childhood cancer experienced financial hardship. Vulnerable sociodemographic status and late effects were associated with hardship. Survivors with financial hardship had an increased risk of symptom prevalence and impaired HRQOL.

Over the past 50 years, incremental improvements in therapies have increased the survival rates of most childhood cancers (1). However, survivors often experience substantial burden from chronic health conditions (2,3), physical and neurocognitive deficits (4,5), symptom prevalence, and suboptimal health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (6,7). The social and economic impact of this burden is considerable because survivors are less likely to graduate from college, assume higher-skilled occupations, or earn higher income than siblings (8–10). The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) has reported that survivors incur higher out-of-pocket medical costs than siblings (11).

“Financial hardship” (financial distress due to cancer diagnosis or treatment) and “financial toxicity” (adverse impact of financial hardship on health outcomes) are emerging concepts to describe financial issues faced by cancer populations. A taxonomy has recently been proposed to study these concepts: material conditions (expenses or bills related to medical care), psychological responses (worry/distress due to costs), and coping behaviors (skipped care or medications) (12). Approximately 30% of US adult cancer survivors have financial problems (13,14). Risk factors of material and/or psychological hardship among adult cancer survivors include middle age (41–65 years) at study participation (14,15), female sex (14–16), minority race/ethnicity (African American, Hispanic) (14–17), lower educational attainment (15,18) and household income (15,17,18), unemployment (17), shorter time since diagnosis (13), treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy (13), and poor health conditions (17,18). Survivors cope with financial problems by withholding medical care (19). Consequently, financial challenge has been linked to suboptimal HRQOL (14) and increased bankruptcy (20).

The emergence of financial hardship in survivors of childhood cancer is unique, as treatment exposures and subsequent medical complications occurring during early stages of human developmental can jeopardize maturation of human capital (ie, educational attainment, employment, etc.). However, the impacts of treatment toxicity and human capital on financial hardship and the associations of hardship with acquiring insurance, retirement planning, symptom prevalence, suicidal ideation, and HRQOL have been understudied. Medically verified late complications and associations with financial hardship have not yet been identified.

Using data collected from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE), we investigated the prevalence, determinants, and consequences of financial hardship in adult survivors of childhood cancer within a proposed conceptual framework. We hypothesized that 1) demographic (middle-aged at evaluation) and clinical factors (more intense treatment, developing treatment-related chronic health conditions) would increase risk of material, psychological, and coping/behavioral financial hardship; 2) human capital (lower educational attainment, lower household income, unemployment) would outweigh the influence of demographic and clinical variables on financial hardship; and 3) financial challenges could impact health/life insurance affordability, retirement planning, and health outcomes (symptom prevalence, suicidal ideation, and HRQOL).

Methods

Study Sample

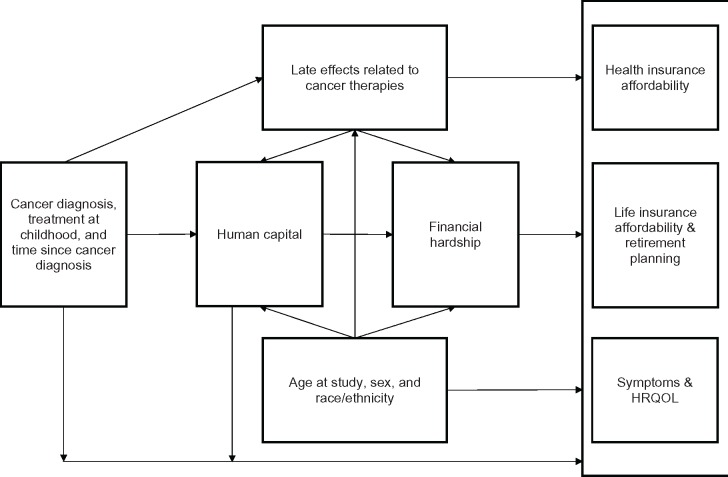

This cross-sectional study utilized data collected from 2811 adult survivors of childhood cancer enrolled in SJLIFE, a retrospective cohort study with prospective clinical follow-up established to investigate etiologies and late treatment effects (3,21). Survivors received comprehensive risk-based medical evaluations consistent with the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Long-term Follow-up Guidelines (22,23). Clinical assessment data were used to categorize 168 specific chronic health conditions using modified Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grading; the severity of each condition was categorized as asymptomatic/mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe/disabling (grade 3), or life threatening (grade 4), as previously reported (24). During clinical evaluations, participants completed a survey that investigated financial situation, health and life insurance affordability, retirement planning, and patient-reported outcomes. Clinical and survey data collected during the first SJLIFE evaluation were used in this study. Figure 1 displays the conceptual framework developed from this study for investigating the determinants and consequences of financial hardship in adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for investigating financial hardship in adult survivors of childhood cancer. HRQOL = health-related quality of life.

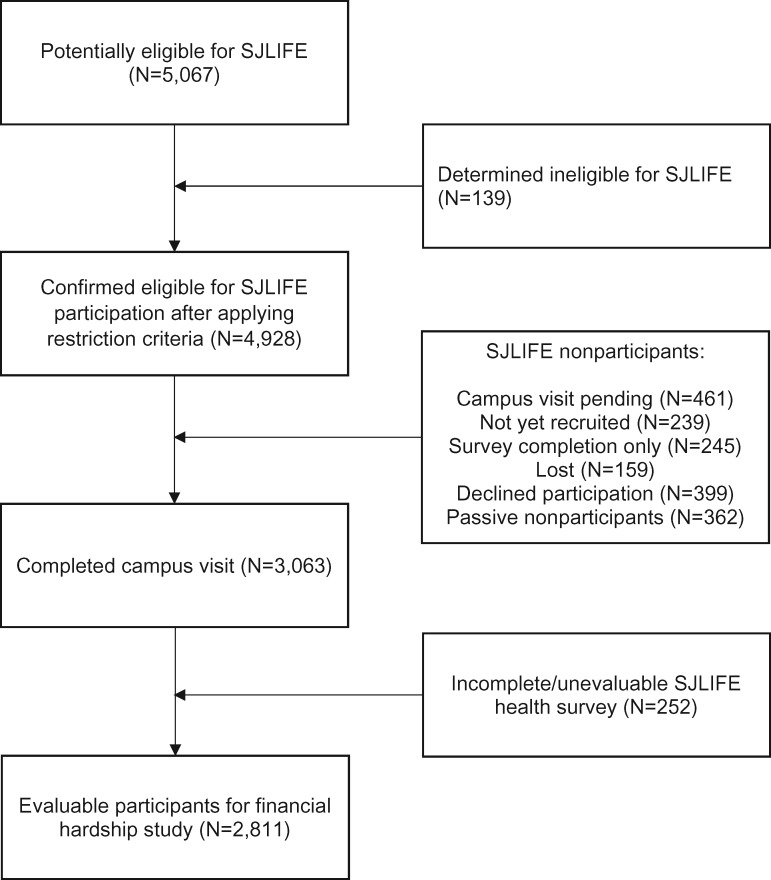

Data Collection

Eligible participants included survivors who were treated at St. Jude since 1962, survived 10 years or longer from diagnosis, and were age 18 years or older at study participation. As of June 2015, 5067 potentially eligible survivors were identified, 4928 were confirmed eligible, 3063 completed an on-campus clinical assessment, and 2811 were included in the analysis (Figure 2). The study protocol was approved by St. Jude’s institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent for evaluations.

Figure 2.

A consort diagram of study participant enrollment. SJLIFE = St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study.

Measures

We used three survey items to evaluate three domains of financial hardship. Material hardship: “Looking back over time since your cancer diagnosis, how much of an impact did your cancer experiences have on your financial situation?” As data related to medical bills/debts were not collected in the SJLIFE survey, we used this general financial impact item as a surrogate of material hardship. This item was derived from the Brief Cancer Impact Assessment (25) and contained five response categories (1 = very negative impact; 2 = somewhat negative impact; 3 = no impact; 4 = somewhat positive impact; 5 = very positive impact), which were further dichotomized into “hardship” (1–2) and “no hardship” (3–5). Psychological hardship: “Concern about ability to cover expenses for health care and prescribed medicine.” This item contained five response categories (1 = very concerned; 2 = somewhat concerned; 3 = concerned; 4 = not very concerned; 5 = not at all concerned), which were further dichotomized into “hardship” (1–3) and “no hardship” (4–5). Coping/behavioral hardship: “You needed to see a doctor or go to the hospital but did not go due to finances.” This item contained two response categories (yes and no).

One item from the SJLIFE survey was used to evaluate health insurance affordability (“Ever had difficulty obtaining health insurance because of your health history”). Two items were used to evaluate life insurance and retirement issues (“Ever had difficulty obtaining life insurance because of health history”; “How much of an impact did your cancer experiences have on retirement plans”). Each item was categorized by two levels (yes and no).

Based on our previous publication (6), seven symptom domains were included: sensation abnormality, cardiac symptoms, pulmonary symptoms, pain, somatization, anxiety, and depression. The last three symptom domains were based on the Brief Symptom Inventory–18 (BSI-18) (26). Suicidal ideation (an item of the BSI-18) was examined independently. HRQOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (27). Physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) were calculated and normalized (mean = 50, SD = 10).

Determinants/Covariates

Determinants of financial hardship included treatment exposures abstracted from medical records, demographics (age at evaluation, sex, and race/ethnicity), socioeconomic status (education, employment, annual household income, number of household members, and marital status), time since diagnosis, and 15 groups of chronic health conditions collected from the clinical evaluation (Supplementary Table 1, available online). To summarize the burden of treatment modalities, each participant was assigned to a low-, moderate-, or high-risk burden group (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Chronic health conditions were categorized as present (CTCAE grades 2–4) or not present (no diagnosed chronic health condition or CTCAE grade 1) (24). These variables were adjusted in the analysis for associations of financial hardship with outcomes of interest.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regressions were performed to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for each financial hardship domain associated with individual determinants. Multinomial logistic regressions were performed to estimate relative risks (RRs) associated with determinants of having hardship in one, two, and three domains vs none. Multivariable logistic regression models were performed to estimate odds ratios for each outcome variable (difficulty in acquiring health and life insurance, retirement planning, and symptom prevalence) associated with each hardship domain, adjusting for the aforementioned covariates. Multivariable linear regression models were performed to test associations of hardship with HRQOL. The variance inflation factor (VIF) index (cutoff ≥ 10) was used to determine multicollinearity among variables associated with financial hardship. Statistically significant differences in analyses were determined by P values of less than .05. Cohen’s metrics were used for comparing HRQOL differences, with 2.0–4.9, 5.0–7.9, and 8.0 or more points indicating small, medium, and large effect sizes (28,29). STATA v14.2 (College Station, TX) was used for all analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 2811 survivors, 57.8% were treated for hematological malignancies, 32.0% for solid tumors, and 10.1% for central nervous system malignancies (Table 1). The mean age at evaluation (SD) was 31.8 (8.4) years, and the mean number of years since diagnosis was 23.6 (8.1). Approximately 30% of survivors had an education level of high school/GED or below, 35.6% had graduated college, 44.5% reported a household income below $40 000, and 23.0% reported $80 000 or above. Compared with nonparticipants, a higher proportion of participants were female, non-Hispanic white, lymphoblastic leukemia leukemia survivors, and treated with invasive surgical procedures (all P < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants and nonparticipants

| Characteristics | Survivors included in this study (n = 2811) | Survivors eligible but excluded from this study (n = 2117)* | P† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at cancer diagnosis (SD), y | 8.3 (5.6) | 8.4 (5.6) | .54 |

| Range, y | 1–24.8 | 1–28.6 | |

| Mean age at evaluation (SD), y | 31.8 (8.4) | –– | |

| Range, y | 18.3–64.5 | ||

| Mean time since cancer diagnosis (SD), y | 23.6 (8.1) | –– | |

| Range, y | 10.0–48.0 | ||

| No. of people supported by household income (SD) | 2.8 (1.4) | –– | |

| Range | 1–9 | ||

| Mean age at evaluation, No. (%) | |||

| 18–29.9 y | 1301 (46.7) | –– | |

| 30–39.9 y | 998 (35.9) | –– | |

| ≥40 y | 485 (17.4) | –– | |

| Mean time since diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| 10–19 y | 1012 (36.0) | –– | |

| 20–29 y | 1127 (40.1) | –– | |

| ≥30 y | 672 (23.9) | –– | |

| Sex, No. (%) | <.001 | ||

| Male | 1454 (51.7) | 1228 (58.0) | |

| Female | 1357 (48.3) | 889 (42.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | <.001 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2170 (80.1) | 1658 (78.3) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 359 (12.8) | 339 (16.0) | |

| Hispanic | 121 (4.3) | 89 (4.2) | |

| Other‡ | 161 (5.7) | 31 (1.5) | |

| Educational attainment, No. (%) | |||

| Below high school | 250 (9.7) | –– | |

| High school graduate/GED | 518 (20.0) | –– | |

| Some college/training after high school | 898 (34.7) | –– | |

| College graduate and above | 920 (35.6) | –– | |

| Employment status, No. (%) | |||

| Currently employed | 1836 (65.3) | –– | |

| Currently unemployed | 975 (34.7) | –– | |

| Annual household income, No. (%) | |||

| ≤$39 999 | 1067 (44.5) | –– | |

| $40 000–$79 999 | 779 (32.5) | –– | |

| ≥$80 000 | 550 (23.0) | –– | |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |||

| Married/living as married | 1083 (40.0) | –– | |

| Status other than married | 1627 (60.0) | –– | |

| Heath insurance status, No. (%) | |||

| Insured | 2141 (77.4) | –– | |

| Uninsured | 624 (22.6) | –– | |

| Cancer diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 947 (33.7) | 590 (27.9) | <.001 |

| Other leukemia | 124 (4.4) | 116 (5.5) | .05 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 348 (12.4) | 219 (10.3) | .02 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 207 (7.4) | 175 (8.3) | .13 |

| Central nervous system malignancy | 285 (10.1) | 247 (11.7) | .05 |

| Sarcomas | 364 (13.0) | 273 (12.9) | .50 |

| Wilms tumor | 186 (6.6) | 138 (6.5) | .47 |

| Neuroblastoma | 129 (4.6) | 89 (4.2) | .28 |

| Retinoblastoma | 80 (2.9) | 63 (3.0) | .43 |

| Other solid malignancies | 141 (5.0) | 207 (9.8) | <.001 |

| Chemotherapy, No. (%) | |||

| Corticosteroids | 1345 (47.9) | –– | |

| Mercaptopurine, thioguanine | 1098 (39.1) | –– | |

| Methotrexate | 1450 (51.6) | –– | |

| Erwinia-/L-/Peg-asparaginase | 943 (33.6) | –– | |

| Cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin | 342 (12.2) | –– | |

| Anthracycline | 1649 (58.8) | –– | |

| Alkylating agents | 1668 (59.7) | –– | |

| Vincristine | 1940 (69.6) | –– | |

| Any chemotherapy | 2322 (82.6) | 1737 (82.1) | .32 |

| Radiotherapy, No. (%) | |||

| Chest | 1516 (54.0) | –– | |

| Abdomen | 1491 (53.1) | –– | |

| Pelvis | 1485 (52.9) | –– | |

| Brain | 1522 (54.3) | –– | |

| Any radiotherapy | 1583 (56.3) | 1064 (59.1) | <.001 |

| Invasive surgery, No. (%) | 1945 (69.2) | 1006 (47.5) | <.001 |

| Burden of treatment modalities,§ No. (%) | |||

| High-risk burden | 1126 (40.2) | –– | |

| Moderate-risk burden | 1276 (45.5) | –– | |

| Low-risk burden | 400 (14.3) | –– | |

| Chronic health conditions,‖ No. (%) | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 103 (3.7) | –– | |

| Cardiac disorder | 260 (9.3) | –– | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 252 (9.0) | –– | |

| Stroke | 89 (3.2) | –– | |

| Upper gastrointestinal disease | 113 (4.0) | –– | |

| Respiratory disorder | 474 (16.9) | –– | |

| Diabetes | 193 (6.9) | –– | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 58 (2.1) | –– | |

| Hepatic disorder | 107 (3.8) | –– | |

| Seizures | 238 (8.5) | –– | |

| Reproductive disorder | 975 (34.7) | –– | |

| Subsequent neoplasm | 190 (6.8) | –– | |

| Skeletal disorder | 284 (10.1) | –– | |

| Hearing loss | 285 (10.1) | –– |

See Figure 2 for the reasons for the exclusion of eligible participants. GED = General Equivalency Diploma.

P values for the comparison between survivors included in this study and survivors eligible but excluded from this study were computed using chi-square tests (two-sided) for binary or categorical variables and Student t tests (two-sided) for continuous variables.

Other: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and Pacific Islander.

High-risk burden: chemotherapy, radiotherapy and invasive surgery, or radiotherapy plus invasive surgery. Moderate-risk burden: chemotherapy plus radiotherapy, chemotherapy plus invasive surgery, radiotherapy only, or invasive surgery only. Low-risk burden: chemotherapy only (Supplementary Methods, available online).

CTCAE grades 2–4 chronic health conditions.

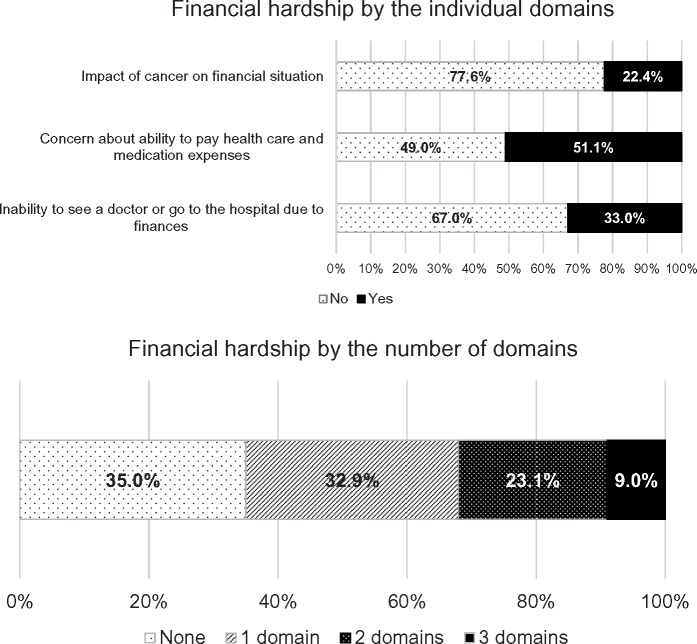

Prevalence of Financial Hardship

Among survivors, 22.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 20.8% to 24.0%) reported material hardship, 51.1% (95% CI = 49.2% to 52.9%) psychological hardship, and 33.0% (95% CI = 31.1% to 34.6%) coping/behavioral hardship (Figure 3). Nearly 65.0% (95% CI = 63.9% to 67.5%) of survivors reported hardship in at least one domain.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of financial hardship in adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Determinants of Financial Hardship

Lower educational attainment, lower household income, and older age at evaluation were the most statistically significant predictors of financial hardship across the three domains (Table 2). An annual household income of $39 999 or less increased risk of material (OR = 3.04, 95% CI = 2.08 to 4.46), psychological (OR = 3.64, 95% CI = 2.76 to 4.80), and coping/behavioral (OR = 4.95, 95% CI = 3.57 to 6.86) hardship (all P < .001), compared with a household income of $80 000 or greater. Survivors who did not complete high school education had a higher risk of material (OR = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.45 to 3.42, P < .001), psychological (OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.18 to 2.62, P < .01), and coping/behavioral (OR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.38 to 3.06, P < .001) hardship compared with those who graduated college or above. Older survivors (age ≥40 years) had elevated risks of psychological (OR = 1.98, 95% CI = 1.38 to 2.85) and coping/behavioral (OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.42 to 3.06) hardship (all P < .001) vs younger survivors (18 to 29.9 years).

Table 2.

Demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical determinants of financial hardship

| Determinants of financial hardship | Material hardship* |

Psychological hardship* |

Coping/ behavioral hardship* |

Any hardship |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | OR (95% CI) | P† | |

| Age at evaluation, y | ||||||||

| 18–29.9 y | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| 30–39.9 | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.73) | .14 | 1.41 (1.10 to 1.81) | .006 | 1.79 (1.37 to 2.34) | <.001 | 1.74 (1.33 to 2.27) | <.001 |

| ≥40 | 1.33 (0.85 to 2.08) | .21 | 1.98 (1.38 to 2.85) | <.001 | 2.08 (1.42 to 3.06) | <.001 | 2.41 (1.61 to 3.60) | <.001 |

| Time since diagnosis, y | ||||||||

| 10–19 | 1.72 (1.14 to 2.60) | .01 | 0.83 (0.60 to 1.15) | .27 | 1.73 (1.21 to 2.46) | .002 | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.54) | .69 |

| 20–29 | 1.38 (0.98 to 1.92) | .06 | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.24) | .70 | 1.44 (1.08 to 1.92) | .01 | 1.08 (0.80 to 1.45) | .64 |

| ≥30 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.16 (0.91 to 1.47) | .24 | 0.88 (0.72 to 1.06) | .18 | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.11) | .33 | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.02) | .07 |

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.82 (0.57 to 1.18) | .28 | 1.09 (0.80 to 1.49) | .59 | 1.22 (0.89 to 1.66) | .21 | 1.15 (0.80 to 1.64) | .46 |

| Hispanic | 0.75 (0.37 to 1.49) | .41 | 1.30 (0.80 to 2.12) | .30 | 0.75 (0.42 to 1.33) | .32 | 1.28 (0.76 to 2.15) | .36 |

| Other‡ | 0.66 (0.38 to 1.17) | .15 | 1.12 (0.75 to 1.68) | .58 | 1.13 (0.73 to 1.75) | .58 | 1.21 (0.78 to 1.86) | .39 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Below high school | 2.22 (1.45 to 3.42) | <.001 | 1.75 (1.18 to 2.62) | .006 | 2.05 (1.38 to 3.06) | <.001 | 3.35 (2.01 to 5.61) | <.001 |

| High school graduate/GED | 1.44 (1.03 to 2.02) | .03 | 1.46 (1.10 to 1.93) | .008 | 1.96 (1.46 to 2.64) | <.001 | 2.43 (1.76 to 3.34) | <.001 |

| Some college/training after high school | 0.94 (0.70 to 1.27) | .67 | 1.39 (1.11 to 1.74) | .004 | 1.88 (1.47 to 2.42) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.28 to 2.05) | <.001 |

| College graduate or above | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Currently employed | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Currently unemployed | 1.79 (1.33 to 2.41) | <.001 | 1.23 (0.93 to 1.62) | .15 | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.43) | .59 | 1.76 (1.24 to 2.48) | .001 |

| Annual household income | ||||||||

| ≤$39 999 | 3.04 (2.08 to 4.46) | <.001 | 3.64 (2.76 to 4.80) | <.001 | 4.95 (3.57 to 6.86) | <.001 | 4.16 (3.12 to 5.54) | <.001 |

| $40 000–$79 999 | 1.63 (1.11 to 2.39) | .01 | 1.79 (1.38 to 2.32) | <.001 | 2.07 (1.50 to 2.86) | <.001 | 2.00 (1.54 to 2.58) | <.001 |

| ≥$80 000 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| No. of people supported by household income | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) | .10 | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) | .27 | 1.09 (1.00 to 1.17) | .04 | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) | .30 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Status other than married | 1.41 (1.08 to 1.85) | .01 | 1.38 (1.11 to 1.71) | .003 | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.45) | .22 | 1.54 (1.23 to 1.94) | <.001 |

| Burden of treatment modalities§ | ||||||||

| Low-risk burden | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Moderate-risk burden | 1.49 (0.98 to 2.28) | .06 | 1.51 (1.12 to 2.02) | .007 | 1.19 (0.86 to 1.64) | .30 | 1.56 (1.15 to 2.12) | .004 |

| High-risk burden | 1.75 (1.14 to 2.68) | .01 | 1.57 (1.16 to 2.13) | .004 | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.60) | .43 | 1.58 (1.15 to 2.17) | .005 |

| Chronic health conditions (CTCAE grades 2–4 vs grade 1 or no condition) | ||||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 2.55 (1.53 to 4.25) | <.001 | 1.88 (1.12 to 3.15) | .02 | 0.90 (0.54 to 1.50) | .68 | 2.22 (1.19 to 4.15) | .01 |

| Cardiac disorder | 1.39 (0.96 to 2.00) | .08 | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.70) | .24 | 1.09 (0.77 to 1.53) | .63 | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.81) | .25 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 2.26 (1.55 to 3.29) | <.001 | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.57) | .67 | 1.20 (0.84 to 1.73 | .31 | 1.55 (0.95 to 2.53) | .08 |

| Stroke | 2.17 (1.15 to 4.09) | .02 | 1.02 (0.57 to 1.84) | .94 | 0.64 (0.33 to 1.23) | .18 | 1.38 (0.68 to 2.78) | .37 |

| Upper gastrointestinal disease | 1.74 (1.03 to 2.93) | .04 | 0.94 (0.58 to 1.53) | .80 | 1.58 (0.97 to 2.57) | .07 | 1.52 (0.85 to 2.72) | .16 |

| Respiratory disorder | 1.14 (0.84 to 1.56) | .40 | 1.18 (0.91 to 1.54) | .22 | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.43) | .57 | 1.13 (0.84 to 1.52) | .41 |

| Diabetes | 1.22 (0.77 to 1.93) | .39 | 1.17 (0.81 to 1.71) | .40 | 1.03 (0.70 to 1.51) | .90 | 1.18 (0.78 to 1.79) | .44 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.57 (0.23 to 1.41) | .22 | 1.47 (0.75 to 2.90) | .27 | 0.99 (0.48 to 2.02) | .97 | 1.04 (0.49 to 2.18) | .92 |

| Hepatic disorder | 1.11 (0.62 to 1.97) | .73 | 1.15 (0.69 to 1.90) | .60 | 1.39 (0.84 to 2.30) | .20 | 1.86 (0.98 to 3.50) | .06 |

| Seizures | 1.74 (1.16 to 2.60) | .007 | 1.02 (0.71 to 1.48) | .90 | 0.68 (0.45 to 1.01) | .06 | 1.45 (0.94 to 2.22) | .09 |

| Reproductive disorder | 1.38 (1.08 to 1.77) | .01 | 1.27 (1.04 to 1.55) | .02 | 1.40 (1.13 to 1.74) | .002 | 1.36 (1.09 to 1.70) | .006 |

| Subsequent neoplasm | 2.29 (1.51 to 3.49) | <.001 | 1.18 (0.81 to 1.72) | .38 | 0.94 (0.63 to 1.40) | .75 | 1.59 (1.03 to 2.45) | .04 |

| Skeletal disorder | 1.36 (0.93 to 1.98) | .12 | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.33) | .82 | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.70) | .29 | 1.16 (0.82 to 1.65) | .41 |

| Hearing loss | 1.47 (1.00 to 2.14) | .05 | 0.76 (0.54 to 1.07) | .11 | 0.71 (0.49 to 1.04) | .08 | 1.05 (0.71 to 1.54) | .82 |

| Amputation | 2.15 (1.12 to 4.15) | .02 | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.23) | .20 | 1.00 (0.54 to 1.87) | .99 | 0.81 (0.43 to 1.53) | .52 |

Material hardship: “impact of cancer on financial situation”; psychological hardship: “concern about ability to pay health care and medication expenses”; coping/behavioral hardship: “inability to see a doctor or go to the hospital due to finances.” CI = confidence interval; CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; GED = General Equivalency Diploma; OR = odds ratio.

P values were computed based on logistic regression models (two-sided).

Other: American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, and Pacific Islander.

High-risk burden: chemotherapy, radiotherapy and invasive surgery, or radiotherapy plus invasive surgery. Moderate-risk burden: chemotherapy plus radiotherapy, chemotherapy plus invasive surgery, radiotherapy only, or invasive surgery only. Low-risk burden: chemotherapy only (Supplementary Methods, available online).

CTCAE grade 2–4 myocardial infarction (P < .001), peripheral neuropathy (P < .001), subsequent neoplasm (P < .001), seizure (P = .007), stroke (P = .02), reproductive disorder (P = .01), amputation (P = .02), upper gastrointestinal disease (P = .04), and hearing loss (P = .05) were each associated with material hardship, with odds ratios ranging from 1.38 (reproductive disorder) to 2.55 (myocardial infarction). Predictors of psychological hardship included having a CTCAE grade 2–4 myocardial infarction (P = .02) and reproductive disorder (P = .02). Survivors treated with modalities associated with a high- (vs low-) risk disease burden had increased risk of material (P = .01) and psychological (P = .004) hardship. Lower educational attainment and household income, unemployment, older age at evaluation, and CTCAE grade 2–4 conditions (myocardial infarction, peripheral neuropathy, and reproductive disorder) were associated with a higher number of hardship domains (Supplementary Table 2, available online). VIFs for all determinants were approximately 2.5, suggesting a weak multicollinearity.

Financial Hardship and Insurance Affordability and Retirement Challenge

Financial hardship across three domains was statistically significantly associated with difficulty in acquiring health and life insurance and poor retirement planning (Table 3). There was a three-, two-, and 10-fold greater risk, respectively, in acquiring health insurance, life insurance, and impact on retirement planning for those with hardship on one or more domains vs none (all P < .001). A higher number of hardship domains was associated with more difficulty in acquiring insurance and retirement planning (Supplementary Table 3, available online).

Table 3.

Associations of financial hardship with health and life insurance affordability and retirement planning

| Type of financial hardship | Difficulty in acquiring health insurance |

Difficulty in acquiring life insurance |

Impact on retirement planning |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P* | OR (95% CI) | P* | OR (95% CI) | P* | |

| Bivariate analysis | ||||||

| Material hardship† | 2.41 (1.98 to 2.92) | <.001 | 2.73 (2.15 to 3.47) | <.001 | 22.04 (17.00 to 28.58) | <.001 |

| Psychological hardship† | 2.89 (2.40 to 3.48) | <.001 | 1.97 (1.59 to 2.43) | <.001 | 2.48 (1.97 to 3.11) | <.001 |

| Coping/behavioral hardship† | 2.27 (1.90 to 2.72) | <.001 | 1.60 (1.29 to 1.99) | <.001 | 2.19 (1.76 to 2.71) | <.001 |

| Any hardship | 3.23 (2.60 to 4.01) | <.001 | 2.37 (1.87 to 3.00) | <.001 | 12.81 (8.11 to 20.23) | <.001 |

| Multivariable analysis‡ | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Material hardship | 2.38 (1.84 to 3.07) | <.001 | 2.57 (1.88 to 3.50) | <.001 | 19.86 (14.11 to 27.94) | <.001 |

| Psychological hardship | 3.00 (2.37 to 3.79) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.40 to 2.35) | <.001 | 2.42 (1.79 to 3.28) | <.001 |

| Coping/behavioral hardship | 2.16 (1.71 to 2.71) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.13 to 1.95) | .004 | 1.86 (1.39 to 2.48) | <.001 |

| Any hardship | 3.13 (2.39 to 4.12) | <.001 | 2.12 (1.59 to 2.83) | <.001 | 10.22 (5.81 to 17.98) | <.001 |

P values were computed based on logistic regression models (two-sided). CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Material hardship: “impact of cancer on financial situation”; psychological hardship: “concern about ability to pay health care and medication expenses”; coping/behavioral hardship: “inability to see a doctor or go to the hospital due to finances.”

Analysis adjusted for age at evaluation, time since diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, the number of people supported by household income, marital status, burden of treatment modalities, and 15 groups of chronic health conditions.

Financial Hardship and Symptoms

Financial hardship across three domains was statistically significantly associated with prevalence of physical and psychological symptoms (all P <.001 for sensation abnormality, somatization, anxiety and depression; all P < .05 for cardiac and pulmonary symptoms and suicidal ideation) (Table 4). However, odds ratios of sensation abnormality, cardiac symptoms, somatization, depression, and suicidal ideation were higher for having coping/behavioral hardship (all P < .001) than having psychological (all P < .01) and material (all P < .05) hardship. Risk of suicidal ideation was greater among those with coping/behavioral (OR = 3.40, 95% CI = 2.33 to 4.96, P < .001), psychological (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.26 to 2.71, P = .002), and material (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.08 to 2.34, P = .02) hardship. An increasing number of hardship domains was associated with greater risk for symptom prevalence (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Table 4.

Associations of financial hardship with symptom prevalence

| Type of financial hardship | Physical symptoms |

Emotional symptoms |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensation abnormality | Cardiac symptom | Pulmonary symptom | Pain | Somatization | Anxiety | Depression | Suicidal ideation | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Bivariate analysis | ||||||||

| Material hardship* | 2.66 (2.21 to 3.20) | 1.82 (1.45 to 2.29) | 2.33 (1.68 to 3.25) | 2.02 (1.58 to 2.57) | 3.35 (2.72 to 4.12) | 3.16 (2.49 to 4.01) | 3.02 (2.42 to 3.77) | 2.54 (1.89 to 3.41) |

| Psychological hardship* | 1.89 (1.60 to 2.22) | 2.02 (1.62 to 2.51) | 2.65 (1.86 to 3.79) | 2.43 (2.02 to 2.91) | 3.57 (2.87 to 4.45) | 3.04 (2.36 to 3.92) | 3.54 (2.79 to 4.49) | 2.60 (1.90 to 3.55) |

| Coping/behavioral hardship* | 2.42 (2.05 to 2.86) | 2.37 (1.92 to 2.93) | 2.79 (2.02 to 3.86) | 3.88 (3.06 to 4.93) | 5.09 (4.14 to 6.26) | 3.73 (2.95 to 4.72) | 4.12 (3.31 to 5.12) | 3.78 (2.82 to 5.07) |

| Any hardship | 2.74 (2.28 to 3.32) | 2.39 (1.84 to 3.08) | 3.08 (1.98 to 4.80) | 2.89 (2.41 to 3.47) | 7.28 (5.25 to 10.09) | 5.24 (3.66 to 7.51) | 6.70 (4.71 to 9.53) | 5.37 (3.36 to 8.58) |

| Multivariable analysis† | ||||||||

| Material hardship | 1.90 (1.48 to 2.43) | 1.50 (1.09 to 2.05) | 1.64 (1.06 to 2.53) | 1.31 (0.97 to 1.79) | 2.41 (1.82 to 3.19) | 2.60 (1.90 to 3.57) | 2.20 (1.64 to 2.96) | 1.59 (1.08 to 2.34) |

| Psychological hardship | 1.66 (1.34 to 2.04) | 1.56 (1.18 to 2.07) | 1.98 (1.26 to 3.11) | 2.03 (1.61 to 2.55) | 2.96 (2.23 to 3.93) | 2.06 (1.50 to 2.83) | 2.39 (1.77 to 3.21) | 1.85 (1.26 to 2.71) |

| Coping/behavioral hardship | 2.40 (1.93 to 2.99) | 2.17 (1.63 to 2.89) | 1.97 (1.30 to 2.99) | 2.93 (2.20 to 3.91) | 3.56 (2.73 to 4.65) | 2.35 (1.73 to 3.18) | 2.89 (2.19 to 3.83) | 3.40 (2.33 to 4.96) |

| Any hardship | 2.28 (1.79 to 2.89) | 1.84 (1.32 to 2.57) | 2.27 (1.28 to 4.03) | 2.38 (1.88 to 3.01) | 5.32 (3.53 to 7.99) | 2.88 (1.89 to 4.40) | 3.57 (2.39 to 5.34) | 3.87 (2.19 to 6.84) |

Material hardship: “impact of cancer on financial situation”; psychological hardship: “concern about ability to pay health care and medication expenses”; coping/behavioral hardship: “inability to see a doctor or go to the hospital due to finances.” CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Analysis adjusted for age at evaluation, time since diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, the number of people supported by household income, marital status, burden of treatment modalities, and 15 groups of chronic health conditions.

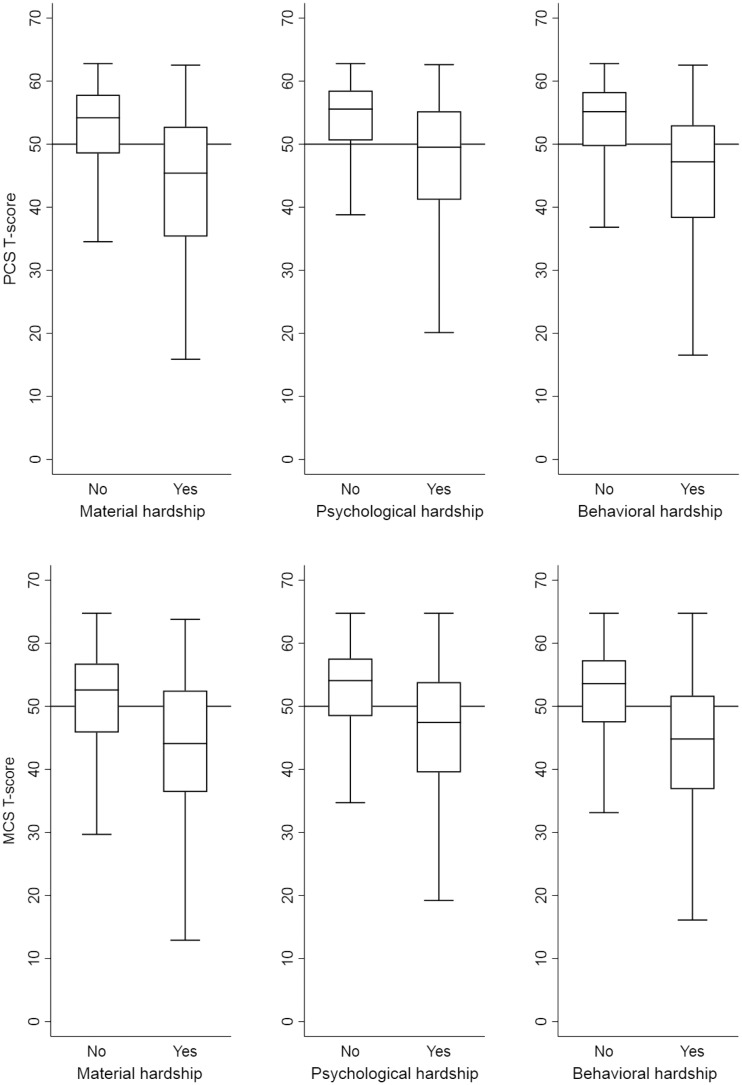

Financial Hardship and HRQOL

Financial hardship across all three domains was statistically significantly associated with lower PCS and MCS (Figure 4). After adjusting for covariates, decreased PCS between those with and without material, coping/behavioral, and psychological hardship were 5.2, 5.0, and 4.1 points (all P < .001). Decreased MCS related to coping/behavioral, material, and psychological hardship were 5.8, 5.1, and 4.6 points (all P < .001). With a higher number of hardship domains, larger decrements in PCS and MCS were observed (Supplementary Table 5, available online). Compared with the norm, there were small effect sizes of suboptimal HRQOL among survivors having a single domain of hardship (approximately three points in both PCS and MCS), but large effect sizes among those having two domains (approximately seven points in both) and three domains (approximately 12 points in both) of hardship.

Figure 4.

Associations of financial hardship with physical component summary (PCS; upper) and mental component summary (MCS; lower). The horizontal line indicates the norm 50 for the SF-36 PCS and MCS. The means (SD) of PCS and MCS of all participants were 50.1 (9.4) and 49.0 (9.6), respectively. The width of each box represents the interquartile range of PCS/MCS, with the upper line for the 75th percentile value, the middle line for the 50th percentile value, and the lower line for the 25th percentile value; the lines extended vertically from the box (whiskers) indicate the highest and lowest values of the study participants.

Discussion

We used patient-reported and clinically ascertained data from a large cohort to investigate determinants of financial hardship and consequences in adult survivors of childhood cancer. This study is a secondary data analysis, and the financial hardship items were designed before the availability of validated tools for measuring financial distress (30) and coping behaviors (31). Evaluating material hardship is particularly challenging due to a lack of consensus regarding definition and measurement (12). Without data describing out-of-pocket medical costs or debts, we queried the degree to which cancer impacted the survivor’s financial situation as a surrogate of material hardship. The use of this metric is more objective (impact) than subjective (distress), with a distinctive pattern of prevalence as compared with other hardship domains (Figure 3). Alternatively, collecting data related to retirement challenges (eg, shortage of retirement savings) as a result of cancer/late effects can also be used to measure material hardship. Despite these limitations, our data are the most comprehensive to date to stress the importance of financial issues among childhood cancer survivors.

It is important to note that we evaluated financial hardship by three domains rather than a composite score, as the latter could not inform how the hardship is related to available financial resources, financial distress, and/or reactions to financial difficulties (12). Overall, 22.4%, 51.1%, and 33.0% of our participants reported hardship in the material, psychological, and coping/behavioral areas, and 65% had hardship in at least one area. The pattern of hardship differs from survey data among adult-onset cancer survivors, where 20% reported material hardship (16), 21% to 23% worried about covering large medical bills (14,16), and 14% to 18% reported forgone/delayed medical care due to finances (13). The discrepancy between this and the national studies may be due to the use of different measures and the characteristics of our participants, who are economically vulnerable, including lower household income, educational attainment, employment rate, and health insurance coverage (32). But our findings reflect the unique financial challenge of childhood cancer survivors, who often develop treatment-related health problems younger than adult-onset cancer individuals (2,33).

Survivors who were older at evaluation, having a lower educational attainment and lower household income or developing late medical effects were more likely to experience financial hardship across three domains than their counterparts. The risk of hardship was higher in the middle-aged group than the young-aged group. Unlike younger survivors who may receive monetary support from parents, middle-aged survivors are more likely to be financially responsible for household expenses. It is evident that childhood cancer survivors have a higher risk of productivity loss than noncancer individuals (34,35), and lower productivity at early life stages has shown decreased earning mobility and financial security in later life (36,37). By extending beyond previous research (38), we identified that specific severe chronic health conditions exacerbated the risk of hardship, especially the material domain, by twofold vs those with no, asymptomatic, or mild conditions. Not surprisingly, this “double-hit” phenomenon places childhood cancer survivors in a disadvantaged situation of adverse psychosocial and health outcomes.

The negative association of financial hardship with acquiring life insurance and retirement planning has not been previously reported, suggesting the occurrence of compounding financial risks when childhood cancer survivors age into their elder years. We found that hardship across three domains decreased the likelihood of acquiring life insurance due to health history by 2.6-fold risk. This is in line with a Dutch study in which 20% of adult survivors endorsed difficulty obtaining life insurance; among them, 61% were rejected by insurance companies (39). Strikingly, the risk of difficulty with retirement planning was increased 20-fold among survivors with material hardship. Unlike older adult-onset cancer survivors who may have accumulated wealth (40), childhood survivors often struggle earning money and securing employment, thereby contributing to a lack of planning for retirement.

Childhood cancer survivors are at higher risk of developing depressive symptoms (7) and suicidal ideation (41) compared with the general population, and suicidal thought has been linked to elevated all-cause mortality (42). The excess risks for depressive symptoms (2.2- to 2.9-fold) and suicidal ideation (1.6- to 3.4-fold) in relation to three hardship domains were independent of the influence of education and income variables found in previous studies (41,43). Interestingly, inability to access health care due to finances was more strongly associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal thought than concerns about the ability to pay medical expenses. Although the mechanism through which financial issues affect symptoms is unknown, bankruptcy (44) and a lack of social integration/support (45) may play a mediating role.

The financial challenges observed in childhood cancer survivors, typically due to late medical effects, emphasize the importance of addressing this issue in a systematic manner (46,47). From the viewpoint of health policy, the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) high-risk insurance plans and state-based exchanges provide subsidized coverage for uninsured cancer survivors; however, cost-sharing under these plans is higher for those who are underemployed (48). The only services covered under the ACA with no out-of-pocket costs are those that meet A/B categories as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Forces (49). Unfortunately, the ACA does not mandate screening tests for late effects, as recommended by the COG (eg, cardiac imaging for cardiomyopathy).

Without amendments to the current policy, early detection in the survivorship care setting, followed by appropriate interventions, becomes critical. In practice, simply asking survivors about their ability to pay for health care could alert the survivorship care team to explore the risks of financial problems (50). Additionally, identifying survivors who forgo/delay medical appointments due to finances and offering hardship-specific coping strategies (51) might prevent depression, suicidal ideation, and other adverse consequences. Useful coping practices/interventions include alleviating negative psychological responses to financial hardship (eg, job-club [52]), supportive education programs to increase financial literacy (53), and navigation systems to address financial barriers during survivorship care (47,54).

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, our results may not be generalizable to all childhood cancer survivors as participants were recruited from a single institution. Compared with the CCSS baseline survey (55), our study contained more participants who were older in age at evaluation, were racial/ethnic minorities, were leukemia and solid tumor survivors, and had no health insurance coverage. Second, financial hardship was measured by extent items included in the SJLIFE. As financial hardship is a new area and tools to measure this concept are still emerging, this limitation highlights an opportunity for future research. Third, the use of cross-sectional data precludes a temporal ascertainment between determinants and consequences of financial hardship. Collecting longitudinal data is necessary to quantify the change of financial status and establish a causal inference of financial hardship with outcomes.

In conclusion, financial hardship is prevalent in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Socioeconomic factors and late effects are related to financial hardship, which in turn affect insurance affordability, retirement planning, and various health outcomes. Future studies are warranted to establish effective strategies to mitigate the impact of financial hardship on childhood cancer survivors.

Funding

This study was supported by US National Cancer Institute grants U01 CA195547 (PIs: MMH and LLR) and P30 CA021765–33 (CORE PI: CR).

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Departments of Biostatistics (DS), Epidemiology and Cancer Control (ICH, NB, TMB, KRK, MMH, LLR), Global Pediatric Medicine (NB), Oncology (MMH), and Psychology (TMB, KRK), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN; Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, GA (JLK).

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

All the co-authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in relation to the work described.

Author contributions: concept and design: ICH; administrative support: TMB, JLK, KRK, MMH, LLR; provision of study materials: MMH, LLR; collection and assembly of data: ICH, NB, MMH, LLR; data analysis and interpretation: ICH, DS; manuscript writing: ICH; editing and final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: An initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet. 2017;39010112:2569–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;30922:2371–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ness KK, Hudson MM, Pui CH, et al. Neuromuscular impairments in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Associations with physical performance and chemotherapy doses. Cancer. 2012;1183:828–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Li C, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3135:4407–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Kenzik K, et al. Association between the prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3133:4242–4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Armstrong GT, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Krull KR.. Emotional distress impacts quality of life evaluation: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;113:309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;2714:2390–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Care. 2010;4811:1015–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirchhoff AC, Krull KR, Ness KK, et al. Occupational outcomes of adult childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2011;11713:3033–3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;3530:3474–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR.. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;1092:djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;11920:3710–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kale HP, Carroll NV.. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;1228:283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;105:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: Findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;343:259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;1233:476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park J, Look KA.. Relationship between objective financial burden and the health-related quality of life and mental health of patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2018;142:e113–ee21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kirchhoff AC, Lyles CR, Fluchel M, Wright J, Leisenring W.. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer. 2012;11823:5964–5972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;326:1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: Study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;565:825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;2224:4979–4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, Version 4.0 Children’s Oncology Group; 2013.

- 24. Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, et al. Approach for classification and severity grading of long-term and late-onset health events among childhood cancer survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarke. Prev. 2017;265:666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Cancer Impact Assessment among breast cancer survivors. Oncology. 2006;703:190–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Derogatis L. Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD.. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;306:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: The Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3117:2136–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;12020:3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;184:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. US Census Bureau. 2010. Census data. http://www.census.gov/2010census/data/. Accessed March 2, 2018.

- 33. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;35515:1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3130:3749–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guy GP Jr, Berkowitz Z, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Yabroff KR.. Annual economic burden of productivity losses among adult survivors of childhood cancers. Pediatrics. 2016;138(supplement):S15–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carr MD, Wiemers EE.. The Decline in Lifetime Earnings Mobility in the U.S.: Evidence from Survey-Linked Administrative Data. Washington, DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corak M. Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. J Econ Perspect. 2013;273:79–102. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rim SH, Guy GP Jr, Yabroff KR, McGraw KA, Ekwueme DU.. The impact of chronic conditions on the economic burden of cancer survivorship: A systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;165:579–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mols F, Thong MS, Vissers P, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse LV.. Socio-economic implications of cancer survivorship: Results from the PROFILES registry. Eur J Cancer. 2012;4813:2037–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;772:109–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Recklitis CJ, Diller LR, Li X, Najita J, Robison LL, Zeltzer L.. Suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;284:655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brinkman TM, Zhang N, Recklitis CJ, et al. Suicide ideation and associated mortality in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2014;1202:271–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;172:435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;349:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berkman LF, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I, Leclerc A, Goldberg M.. Social integration and mortality: A prospective study of French employees of Electricity of France-Gas of France: The GAZEL Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;1592:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V.. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores’. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;322:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith SK, Nicolla J, Zafar SY.. Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: A qualitative study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;105:e368–e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, et al. Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: Results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Support Care Cancer 2013;212:377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mueller EL, Park ER, Davis MM.. What the affordable care act means for survivors of pediatric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;327:615–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tran G, Zafar SY.. Price of cancer care and its tax on quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2018;142:69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Head B, Harris L, Kayser K, Martin A, Smith L.. As if the disease was not enough: Coping with the financial consequences of cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;263:975–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Moore TH, Kapur N, Hawton K, Richards A, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D.. Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2017;4706:1062–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hastings JS, Madrian BC, Skimmyhorn WL.. Financial literacy, financial education and economic outcomes. Annu Rev Econ. 2013;51:347–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Christie J, Itzkowitz S, Lihau-Nkanza I, Castillo A, Redd W, Jandorf L.. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;1003:278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: Prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;244:653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.