Abstract

Cellular antioxidant systems control the levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) within cells. Multiple theoretical models exist that predict the diffusion properties of H2O2 depending on the rate of H2O2 generation and amount and reaction rates of antioxidant machinery components. Despite these theoretical predictions, it has remained unknown how antioxidant systems shape intracellular H2O2 gradients. The relative role of thioredoxin (Trx) and glutathione systems in H2O2 pattern formation and maintenance is another disputed question. Here, we visualized cellular antioxidant activity and H2O2 gradients formation by exploiting chemogenetic approaches to generate compartmentalized intracellular H2O2 and using the H2O2 biosensor HyPer to analyze the resulting H2O2 distribution in specific subcellular compartments. Using human HeLa cells as a model system, we propose that the Trx system, but not the glutathione system, regulates intracellular H2O2 gradients. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 31, 664–670.

Keywords: H2O2 gradients, chemogenetics, thioredoxin reductase, HyPer, D-amino acid oxidase

Introduction

Aerobic organisms use oxygen not only as a terminal electron acceptor in the respiratory chain but also as a source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (7). The stable ROS H2O2 is a molecule with well-established signaling roles, acting mainly via the oxidation of specific thiols. H2O2 is produced locally in cells by various enzymatic systems, including but not limited to NADPH oxidases and components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The spatial and temporal distribution of H2O2 within cells must be controlled by the competing activities and differential distribution of oxidant and antioxidant enzymatic machinery, but is yet little understood. Excessive oxidant production or insufficient oxidant scavenging leads to oxidative stress, a condition associated with many pathological states (7).

Innovation

A major challenge in using imaging approaches to study intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is that endogenous H2O2, its sources, and scavengers are variably present in diverse locations. If some particular H2O2 distribution is visualized, it is not clear how it is shaped by the activity of H2O2 synthesizing and scavenging enzymes. We used a chemogenetic approach to introduce a generator of H2O2 in a clearly defined subcellular location and visualized the resulting H2O2 distribution using the targeted HyPer biosensors. This has allowed us to visualize and dissect peroxide-scavenging activity and to determine the distribution of H2O2 in living cells.

Two major cellular systems of H2O2 metabolism are linked to thioredoxin (Trx) and glutathione (7). Both systems rely on NADPH as a source of electrons for H2O2 reduction via a chain of thiol or selenol exchange events. The glutathione system transfers reducing equivalents from NADPH to glutathione via glutathione reductase, maintaining a millimolar-scale cytoplasmic pool of reduced glutathione (GSH) that can be used to reduce H2O2 by selenoprotein glutathione peroxidases (GPX). The Trx system shuttles reducing equivalents to H2O2 from NADPH via thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) to Trxs that finally efficiently supports reduction of H2O2 by the action of Trx-dependent peroxiredoxins (Prxs). Thiol peroxidases from the Prx family are usually considered to be major H2O2 scavengers in the cytosol and mitochondria. However, in most cases the relative input of Trx and glutathione systems to H2O2 sequestration remains unknown.

Theoretical modeling predicts that the diffusion distance of H2O2 within the cytosol is restricted to few micrometers (9) because of the very high concentration and reaction rates of intracellular peroxidases. Studies using genetically encoded sensors suggest an even smaller diffusion distance (6). However, there have been only limited attempts to visualize the activities of cellular antioxidant machinery. For example, the biosensor Trx-RFP allows Trx activity monitoring (4), but interpretation of results using Trx-RFP is confounded by the fact that Trx is itself a source of electrons for Prx enzymes, and has no direct role in H2O2 degradation. Another problem in visualization of H2O2-scavenging activity is that the enzymatic sources of H2O2 generation are dynamically targeted within specific subcellular domains, such that the precise location of the intracellular H2O2 source cannot be determined. The observed pattern of H2O2 distribution within the cell would be a result of interference between an unknown pattern of oxidant production and another unknown pattern of antioxidant activity. Therefore, H2O2 itself should preferentially be monitored under well-controlled conditions if H2O2 gradients are to be understood.

We rationalized that engineering a cell-based system where a chemogenetic H2O2 generator has a precise known location within the cell in combination with a detector for H2O2 anchored to a network of relatively immobile subcellular structures would help visualize how antioxidant activity shapes the patterns of H2O2 metabolism within the cell.

Results, Discussion, and Future Directions

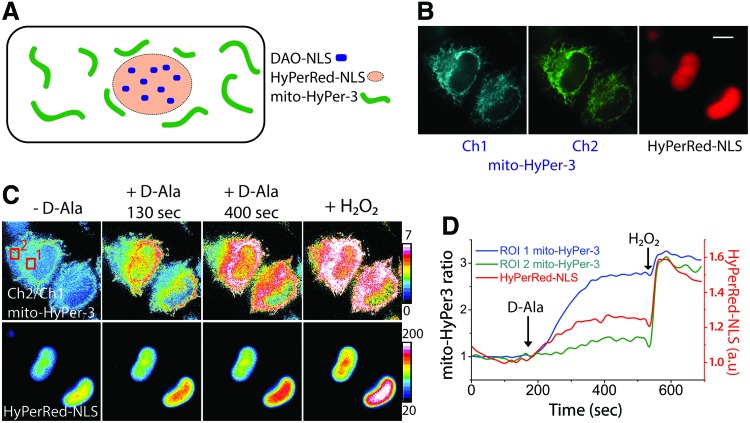

To generate H2O2, we targeted yeast d-amino acid oxidase (DAO) to the cell nucleus by fusing DAO with a nucleus localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 1A). DAO remains inactive in the absence of its D-amino acid substrates but when provided with D-alanine (D-Ala), DAO generates submicromolar amounts of H2O2 (5). Targeting DAO to the nucleus ensures that upon D-Ala addition, H2O2 will be produced within the nucleus, generating a clearly defined spatiotemporal pattern of H2O2 generation.

FIG. 1.

Chemogenetic H2O2 gradient visualized by mitochondria-targeted HyPer-3. (A) The scheme of the H2O2 generation/detection system in which the DAO-NLS construct generates H2O2 in the nucleus only when provided its D-Ala substrate. The H2O2 biosensor HyPerRed-NLS is targeted to the cell nucleus to monitor local H2O2 production by nuclear-targeted DAO, whereas the mitochondria-targeted mito-HyPer-3 detects the spread of H2O2 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm/mitochondria. (B) Representative images of the cells imaged in three fluorescent channels: two for HyPer-3 and one for HyPerRed. Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) The upper row shows ratiometric images of the same cells from panel (B) analyzed after the addition of D-Ala. After D-Ala is added, H2O2 generation in the nucleus is monitored with HyPerRed-NLS (lower row). H2O2 exiting the nucleus forms the gradient visible using mito-HyPer-3. For quantification, two ROIs are selected, as shown. ROI1 is selected at the periphery of the nucleus, while ROI2 is at a region distant from the nucleus. (D) Time course of H2O2 changes within the ROI1, ROI2 and in the nucleus of the cell shown on panel (C). These results show that the mito-HyPer-3 in ROI1 becomes almost completely oxidized by H2O2 exiting the nucleus, whereas in ROI2 the HyPer-3 remains reduced. D-Ala, D-alanine; DAO, d-amino acid oxidase; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; NLS, nucleus localization signal; ROI, regions of interest. Color images are available online.

To visualize H2O2 release from the nucleus, we used HyPer-3, a ratiometric genetically encoded probe (2). When used in a nonlocalized version, HyPer-3 diffuses freely within the nucleocytosolic compartment, making it impossible to visualize H2O2 gradients within any specific subcellular compartment. However, the HyPer biosensor can be targeted to specific subcellular organelles permitting analyses of H2O2 emanating from a distinct H2O2 source (6). We used here the probe targeted to the mitochondrial matrix because the mitochondria form a stable network within the cell and maintain their positions within the cell over the time course of the experiment. A nucleus-localized DAO as a chemogenetic generator of H2O2, together with mito-HyPer-3 sensor, allows us to answer several key questions: Would H2O2 produced by DAO-NLS be able to exit the nucleus? If so, how far would it diffuse? Which branch of the cellular antioxidant systems can regulate the distribution of H2O2 within cells?

To answer these questions, we transfected HeLa-Kyoto cells with plasmids encoding DAO-NLS along with both the nucleus-targeted biosensors HyPerRed-NLS (3) and mitochondria-targeted mito-HyPer-3 (Fig. 1A, B). HyPerRed-NLS serves to monitor H2O2 production in the nucleus, and mito-HyPer-3 permits visualization of the spatiotemporal distribution of H2O2 in mitochondria outside of the nucleus. Addition of 4 mM D-Ala to the cells led to H2O2 production in the nucleus, measured as the increase of HyPerRed-NLS signal. As oxidation of HyPerRed is usually incomplete under these conditions, we assume that DAO activity leads to <200 nM H2O2 in the nucleus. After being produced within the nucleus, H2O2 immediately appeared in the cytoplasm and started to oxidize HyPer-3 in the mitochondria surrounding the nucleus, but not in distant peripheral mitochondria (Fig. 1C, D; Supplementary Video S1). Addition of excess of exogenous H2O2 led to equal and complete oxidation of mito-HyPer-3 in the perinuclear and distant mitochondria.

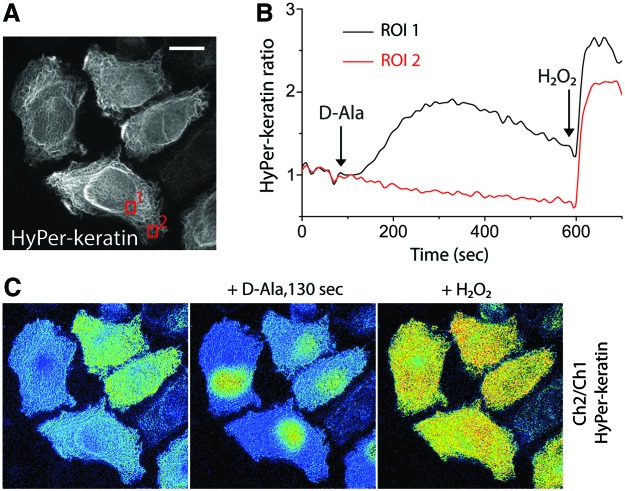

Visualization of an engineered H2O2 gradient by the HyPer-3 probe targeted to the mitochondrial matrix does not exclude the possibility of direct transfer of H2O2 between the nucleus and the mitochondrial matrix without passing the cytosol, although the mechanistic basis of such putative transport is unknown. We therefore sought to find a means to visualize the H2O2 gradient also in the cytosol. Toward this end, we created a fusion protein between HyPer and keratin, an intermediate filament that forms a relatively stable network within the cytosol. Linking HyPer to keratin prevents the rapid diffusion of the biosensor within the cytosolic compartment. Addition of D-Ala to cells expressing keratin-HyPer and DAO-NLS led to a rapid formation of a H2O2 gradient within the cytosol that was of a similar shape to the one that was visualized using the mitochondrial HyPer3 (Fig. 2). HyPer associated with perinuclear filaments demonstrated ball-shaped oxidation pattern, whereas the probe at peripheral filaments was not oxidized. These experiments indicate that the H2O2 gradient formed by DAO-NLS exists in both the cytosol and the mitochondria, with higher levels in proximity to the nucleus.

FIG. 2.

Detecting the chemogenetic H2O2 gradient in the cytosol. (A) Fluorescent images of representative HeLa-Kyoto cells expressing nuclear-targeted DAO-NLS and cytosol-targeted HyPer-keratin showing a stable network of the H2O2 biosensor fusion protein within the cytosol. The ROI1 is in the perinuclear region, and ROI2 is in the cell periphery, as shown by the red boxes in this image. (B) Time course quantitating the D-Ala-induced changes in the HyPer ratio in ROI1 and ROI2. (C) Ratiometric images of the cells shown in panel (A) before and after D-Ala addition, and after saturation with exogenous H2O2. Scale bars = 10 μm. Color images are available online.

There are several possibilities for the cell to prevent the widespread intracellular diffusion of H2O2. Catalase of peroxisomes, glutathione coupled to GPX, and Prxs fueled by the Trx pathway all might play key roles as H2O2 gatekeepers.

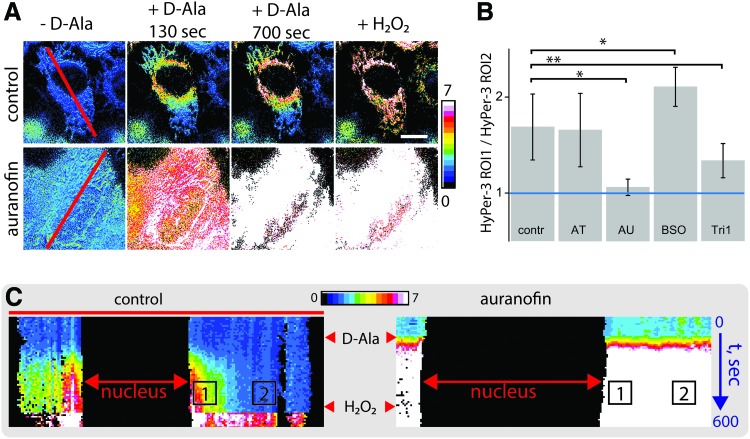

To explore these different possibilities, we used a series of inhibitors, which we then evaluated using a simple quantification strategy. The H2O2 gradient formation leads to a higher HyPer-3 signal in the mitochondria surrounding the nucleus compared with the peripheral zones. Therefore, this gradient can be analyzed as a HyPer-3 ratio profile along a line drawn across the cell (red lines in Fig. 3A). Changes of this profile with time associated with the formation or dissipation of the H2O2 gradient can be visualized as a kymograph where one dimension is the HyPer-3 ratio profile along the line and the second dimension is time: each next line profile taken at t + 1 image is drawn under the previous one from the frame t (Fig. 3C). Then, the first region of interest (ROI1) is selected as the region of the kymograph representing perinuclear mitochondria after D-Ala addition, and ROI2 is associated with the peripheral mitochondria at the same time period. If no gradient exists, the ROI1/ROI2 ratio becomes equal or close to 1, reflecting no difference in HyPer-3 ratio between perinuclear and distant mitochondria. The higher the transcellular H2O2 ratio is the steeper the intracellular H2O2 gradient will be.

FIG. 3.

The intracellular H2O2 gradient is maintained by the thioredoxin system. (A) Ratiometric images of mito-HyPer-3 in DAO-NLS expressing cells. Upper row: control cells form a stable H2O2 gradient in the cytoplasm upon D-Ala addition. Lower row: preincubation of the cells with auranofin leads to uniform basal oxidation of mito-HyPer-3 across the cell that becomes even more extreme with the addition of either D-Ala or exogenous H2O2. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Effects of different redox inhibitors on the H2O2 gradient. The gradient was quantitated as the ratio of the mito-HyPer-3 signal measured in the perinuclear region to the ratio observed in mitochondria located at a distance from the nucleus. A ratio of 1 (shown as a blue line) indicates that no gradient exists. The higher the ratio, the steeper is the H2O2 gradient. Bars show mean ± SD from at least 10 measurements each of 3 biological replicates. *p < 0.001, **p < 0.05 by two-tailed unequal variance t-test. (C) Representative time projections (kymographs) of H2O2 gradients along the lines highlighted in red on panel (A) in control and auranofin-pretreated cells. The numbers “1” and “2” denote ROI1 and ROI2, respectively; these two ROIs were analyzed to quantify the results for panel (B). SD, standard deviation. Color images are available online.

When we analyzed the kymographs, we found that the addition of D-Ala results in ROI1/ROI2 ratio significantly >1, thus reflecting H2O2 gradient formation (Fig. 3B, control bar). Incubation of the cells with the catalase inhibitor 3-AT did not lead to changes in gradient intensity, suggesting that catalase is not involved in the gradient formation. In sharp contrast, preincubation of the cells with auranofin, a potent TrxR inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S1A), led to complete elimination of the gradient (Supplementary Video S2). In this case, addition of D-Ala led to rapid oxidation of HyPer3 in both perinuclear and peripheral mitochondria. Moreover, control addition of extracellular H2O2 at the end of imaging series was unable to further oxidize HyPer3, indicating that the indicator had reached saturation. This indicates that the Trx branch of the intracellular antioxidant system shapes the H2O2 gradient, preventing diffusion of H2O2, likely by means of the Prxs. It should be noted that before addition of D-Ala, the HyPer-3 probe appeared to be mostly reduced, indicating that the lack of the H2O2 gradient was not a result of pre-existing HyPer-3 oxidation caused by the auranofin treatment itself.

Also the glutathione system is involved in H2O2 metabolism via the actions of selenoprotein GPX, which reduce H2O2 to H2O at the expense of glutathione oxidation. We thus hypothesized that suppression of the glutathione system would also lead to attenuation of the H2O2 gradient. To our surprise, treatment of the cells with l-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO), a potent inhibitor of glutathione synthesis (Supplementary Fig. S1B), not only did not destroy the gradient, but, in fact, made it even stronger (Fig. 3B). One possible explanation of this observation could be that inhibition of GSH synthesis leads to compensatory activation of the Trx system. An alternative explanation could be that NADPH normally utilized to maintain a high reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio becomes available for TrxR, enhancing the availability of reducing equivalents to the cellular Prxs.

Auranofin is a potent inhibitor of both cytosolic TrxR1 and mitochondrial TrxR2 (8). It is thereby possible that both of these TrxR isoforms could contribute to the maintenance of H2O2 gradients across the cytoplasm. Alternatively, only cytosolic TrxR1 might be the primary source of reducing equivalents for H2O2 scavenging. To test these two possibilities, we next utilized a newly developed Trx inhibitor, TRi-1, which preferentially inhibits cytosolic TrxR1 over mitochondrial TrxR2 at the concentration 1 μM used in our study (8). Would TRi-1 addition result in the same loss of H2O2 patterning that we observed with auranofin? Preincubation of the cells with TRi-1 indeed led to the destruction of the H2O2 gradient, although not as complete as in case of equimolar concentrations of auranofin (Fig. 3B). This may suggest that cytoplasmic H2O2 gradients are maintained by the concerted action of both TrxR1 and TrxR2, although only the TrxR1 importance for this could here be validated with the partial inhibition of the H2O2 gradient using treatment with the TrxR1 inhibitor TRi-1.

In summary, we have here analyzed engineered H2O2 gradients that are chemogenetically produced by specific intracellular substrate-controlled sources targeted to the cell nucleus (DAO-NLS). H2O2 produced within the nucleus formed a gradient across the cytoplasm. In these cells, the Trx system appeared to be the central determinant establishing the gradient of H2O2 and preventing widespread diffusion of H2O2 within the cytoplasm. Neither catalase nor glutathione appeared to play important role in H2O2 gradient formation. It remains to be determined whether Trx-fueled enzymes play a similar role in other cell types than HeLa cells as used here. It is possible that some cell types are able to use GSH as a source of electrons for spatiotemporal H2O2 control, but that needs to be experimentally addressed in forthcoming studies. It is known, however, that many cancer cells rely on the Trx system more than normal cells (1), and as shown here, the typical HeLa cancer cells also utilize the Trx pathway to promote formation of intracellular H2O2 gradients. We feel that the combination of chemogenetic approaches using differentially targeted DAO with HyPer constructs as demonstrated here will facilitate the analysis of intracellular H2O2 metabolism in diverse experimental systems and in disease states.

Materials

H2O2, D-Ala, D-Glucose, Tyrode's salts, BSO, 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT), and auranofin were purchased from Sigma. TRi-1 was developed and synthesized as described elsewhere (8). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), Opti-minimal essential medium, fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin–streptomycin, and FastDigest restriction endonucleases were from ThermoFisher Scientific. Tersus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit and Quick ligation kit were from Evrogen. 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and FuGeneHD transfection reagent were from Promega. Glass-bottomed dishes were from WPI. The HeLa-Kyoto cell line was provided by Carsten Schultz, EMBL.

DNA constructs

The pCAGGS-HyPer-keratin construct was generated by overlap extension PCR cloning. HyPer was amplified from pC1-HyPer (Evrogen) with primers 5′-GCAACGCCTCTGACGGTGGTGGGTCTGGTGGTATGGAGATGGCGAGCCAGC-3′ and 5′-AATTTCTAGATTAAACCGCCTGTTTTAAAACTTTATCGAAATGGC-3′ and keratin was amplified from pTagRFP-keratin (Evrogen) with primers 5′-AATTGAATTCGCCACCATGAGCTTCACCACTCGCTCCA-3′ and 5′-CCACCGTCAGAGGCGTTGCCCCCAGTTCCGGAATGCCTCAGAACTTTGGTGTCATTGGT-3′. The fused PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XbaI, and ligated into pCAGGS-Raichu-RhoA-CR (Addgene 40258).

To generate pC1-DAO-NLS, DAO-NLS was amplified from pCMV-DAO (2) with primers 5′-ACCGCTAGCGCCACCATGCAATTGCACAGCCAGAAGAGG-3′ and 5′-ACCAAGCTTTTACTACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCTACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCTACCTTTCTCTTCTTTTTTGGATCGCTCTCCCTAGCTGCGC-3′. The PCR product was digested with NheI and HindIII, and ligated into predigested pHyPer-nuc (Evrogen) with removed HyPer coding region.

To generate pC1-HyPerRed-NLS, HyPerRed was amplified from pC1-HyPer-Red (Addgene 48249) with primers 5′-AATTGCTAGCGCCACCATGGAGATGGCGAGCCAGC-3′ and 5′-AATTAGATCTGAGTCCGGAAACCGCCTGTTTTAAAACTTTATCGAAATGGC-3′. The PCR product was digested with NheI and BglII, and ligated into predigested pHyPer-nuc (Evrogen).

To generate pLCMV-HyPer3-mito, HyPer3 was amplified from pC1-HyPer3 (Addgene 42131) using the primers 5′-ATCTGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACCGAGATGGCGAGCCAGCA-3′ and 5′-CGCAGTCGACTTAAACCGCCTGTTTTAAAACTTTATCG-3′. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and SalI. Duplicated mitochondrial targeting sequence (dMito) was cut out from pHyPer-dMito vector (Evrogen) with NheI and BamHI. HyPer3 and dMito restriction products were ligated into pLCMV-Puro vector digested with NheI and SalI.

All constructs were confirmed by full sequence analysis.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa-Kyoto cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10% FCS at 37°C in atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were split every second day and seeded on glass-bottomed dishes. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transfected by the mixture of vector DNA and FuGeneHD transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Imaging

Forty-eight hours after transfection culture medium was replaced with 1.8 mL preheated Tyrode's salt solution supplemented with 20 mM HEPES and additional 20 mM glucose and imaged using a Leica 6000 widefield microscope equipped with HCX PL APO lbd.BL 63 × 1.4NA oil objective and a thermostating box. Fluorescence of HyPer probe was excited sequentially via 427/10 and 504/12 bandpass excitation filters. Emission was collected every 10 or 15 s using a 525/50 bandpass emission filter. For HyPerRed probe, TX2 filter cube was used (excitation: BP 560/40, dichromatic mirror 595, emission: BP 645/75). After 10–12 images were acquired, 200 μL Tyrode with D-Ala was added to the final concentration of 5–8 mM. One hundred fifty micromolars H2O2 was added at the end of every experiment for maximal oxidation of HyPer.

Inhibitor treatments

BSO and 3-AT were dissolved in mQ at stock concentrations of 100 mM and 1 M, respectively, and stored frozen at −20°C. Cells were preincubated with 0.5 mM BSO for 22 h and 10 mM 3-AT for 2 h before the imaging.

Auranofin was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at stock concentration of 14.3 mM and stored at 4°C. Auranofin and TRi-1 were added to the cells at a concentration of 1 μM and incubated for 1 h before the imaging.

Measurement of TrxR activity and GSH content in cells treated with inhibitors

For measurement of TrxR activity, we used Thioredoxin Reductase Assay Kit (ab83463; Abcam). In the assay, TrxR catalyzes NADPH-dependent reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic) acid (DTNB) to 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid (TNB2−), which generates a strong yellow color (λmax = 412 nm). Inhibitors auranofin and Tri-1 were added to HeLa-Kyoto cells at concentrations of 1 and 10 μM, after which cells were incubated for 1 h. Cells treated with the same volume of DMSO (5 μL) were used as control. For sample preparation, we used 2 × 106 cells. All measurements were carried out in transparent flat-bottom 96-well plates (Corning) on plate reader Tecan Infinite 200 Pro in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Abcam). Kinetic curves were measured on OD 412 nm during 100 min.

For measurement of total glutathione, we used GSH/GSSG Ratio Detection Assay Kit II (ab205811; Abcam). This kit uses a proprietary nonfluorescent dye that becomes strongly fluorescent upon reacting directly with GSH. For the assay, HeLa-Kyoto cells were incubated with 0.5 mM BSO for 22 h. Untreated cells were used as control. For sample preparation, we used 3 × 106 cells. All measurements were carried out in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. We monitored fluorescence at Ex/Em = 490/520 nm on plate reader Tecan Infinite 200 Pro using black flat-bottom 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One).

The protein concentration for both protocols was determined by using Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (BCA1 AND B9643; Sigma Aldrich).

Time-series processing

Time series were analyzed using Fiji ImageJ free software. The background was subtracted from 420- to 500-nm stacks (correspond to two HyPer excitation peaks). Images were converted to 32 bits, and a 420-nm stack was thresholded to remove pixel values from the background (Not-a-Number function). A 500-nm stack was divided into a 420-nm stack frame by frame. The resulting stack was depicted in pseudocolors using a “16-colors” lookup table. Time course of HyPer fluorescence was calculated for ROIs inside the imaged cell. For Figures 1 and 2, two ROIs were set up for each cell corresponding to the perinuclear region (ROI1) and the distal region (ROI2—12–16 μm from the nucleus).

For Figure 3, kymographs were generated from HyPerRed-NLS image stack (nucleus) and HyPer3-mito ratio image stack (mitochondria) by averaging across 9 pixels wide ROIs (e.g., indicated by red lines shown in Fig. 3A). Using HyPerRed-NLS kymograph, HyPer3-mito kymograph was thresholded to remove pixel values from a nuclear region (Not-a-Number function) to make resulting kymograph for each cell (e.g., Fig. 3C). Two ROIs were set up for each resulting kymograph corresponding to the perinuclear region (ROI1) and the distal region (ROI2—13 μm from ROI1), and a ROI1/ROI2 value was calculated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant 17-14-01086 and DFG IRTG 1816 to V.V.B., and by grants to T.M. from the NIH (P30 DK057521), and from a Brigham and Women's Hospital Health and Technology Innovation Award, and by grants to E.J.S.A. from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundations. Several experiments were carried out using the equipment provided by the IBCH core facility (CKP IBCH, supported by Russian Ministry of Education and Science, grant RFMEFI62117X0018).

Abbreviations Used

- 3-AT

3-amino-1,2,4-triazole

- BSO

L-buthionine sulfoximine

- D-Ala

D-alanine

- DAO

d-amino acid oxidase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- GPX

glutathione peroxidases

- GSH

glutathione

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- NLS

nucleus localization signal

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- Prx

peroxiredoxin

- ROI

region of interest

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Trx

thioredoxin

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Arnér ESJ. Targeting the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1 for anticancer therapy. Adv Cancer Res 136: 139–151, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bilan DS, Pase L, Joosen L, Gorokhovatsky AY, Ermakova YG, Gadella TW, Grabher C, Schultz C, Lukyanov S, and Belousov VV. HyPer-3: a genetically encoded H2O2 probe with improved performance for ratiometric and fluorescence lifetime imaging. ACS Chem Biol 8: 535–542, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ermakova YG, Bilan DS, Matlashov ME, Mishina NM, Markvicheva KN, Subach OM, Subach FV, Bogeski I, Hoth M, Enikolopov G, and Belousov VV. Red fluorescent genetically encoded indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Commun 5: 5222, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fan Y, Makar M, Wang MX, and Ai HW. Monitoring thioredoxin redox with a genetically encoded red fluorescent biosensor. Nat Chem Biol 13: 1045–1052, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matlashov ME, Belousov VV, and Enikolopov G. How much H(2)O(2) is produced by recombinant D-amino acid oxidase in mammalian cells? Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 1039–1044, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mishina NM, Tyurin-Kuzmin PA, Markvicheva KN, Vorotnikov AV, Tkachuk VA, Laketa V, Schultz C, Lukyanov S, and Belousov VV. Does cellular hydrogen peroxide diffuse or act locally? Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 1–7, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sies H, Berndt C, and Jones DP. Oxidative stress. Annu Rev Biochem 86: 715–748, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stafford WC, Peng X, Olofsson MH, Zhang X, Luci DK, Lu L, Cheng Q, Trésaugues L, Dexheimer TS, Coussens NP, Augsten M, Ahlzén HM, Orwar O, Östman A, Stone-Elander S, Maloney DJ, Jadhav A, Simeonov A, Linder S, and Arnér ESJ. Irreversible inhibition of cytosolic thioredoxin reductase 1 as a mechanistic basis for anticancer therapy. Sci Transl Med 10: 428, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Winterbourn CC. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat Chem Biol 4: 278–286, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.