Abstract

Azobenzenes are the most widely studied photoswitches, and have become popular optical probes for biological systems. The cis configuration is normally metastable, meaning the trans configuration is always thermodynamically favored. The unique exception to this rule is an azobenzene having a two-carbon bridge between ortho positions, substitutions that lock the photoswitch in its cis configuration. Only thoroughly chemically characterized relatively recently, we describe the first applications of this locked-azobenzene (or “LAB”) scaffold with two derivatives designed to control ion flow in pyramidal neurons in acutely isolated brain slices. Our LAB derivatives maintain most of the desirable photochemical properties of the parent scaffold, and work as designed in living cells. However, LAB derivitization changes the trans photostationary state from >85% of the parent photoswitch to about 50%, suggesting that careful design considerations must be given for future applications of the LAB scaffold in biological areas.

Keywords: photoswitch, azobenzene, glutamate switch, potassium channels, visible light, reversible

Introduction.

Photochemical molecular switches are chromophores that exist in two stable configurations which bestow upon each distinct chemical properties(1–4). In a biological context such molecules were originated by Erlanger and co-workers in 1968(5). They controlled the kinetics of enzyme inactivation by photochemically sculpting of the bulk of an acylating reagent. They found that an azobenzene (AB) derivative of a chymotrypsin-specific drug was five times more reactive in its cis configuration than its thermodynamically favored trans configuration. Ultraviolet light (320 nm) was used to cause trans to cis isomerization, and violet light (420 nm) photoreversion to the trans configuration. Erlanger and co-workers presented their ground breaking a model of naturally occurring “light-sensitive metabolic systems present in living organisms”. Processes such as visual transduction and photosynthesis are now well characterized at the atomic and physiological levels, so perhaps the lasting impact of this seminal contribution is most felt in the new field of what is called “photophamacology”(6). While chemists have invented many different photochromic systems(2), the AB chromophore used by Erlanger in 1968 remains most popular and useful in this field(1).

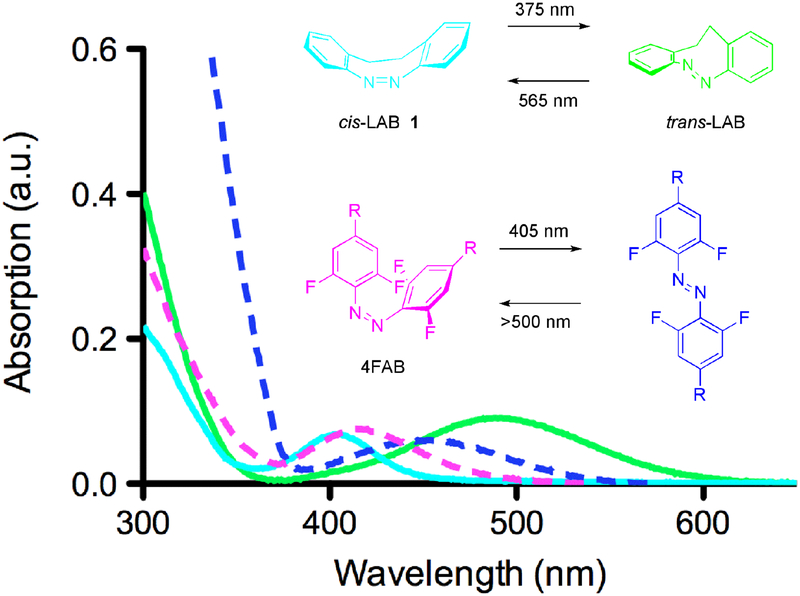

A common feature of all AB photoswitches is that the trans configuration is the thermodynamically favored form(7). Recently, an exception (1, Figure 1) to this rule was well-characterized chemically by the groups of Herges, Renth and Temp(8). Known since 1910(8), the photoswitch scaffold 1, which we called locked-AB (or “LAB”), exists in the dark in its cis configuration completely. The two-carbon bridge between the ortho positions locks the chromophore in what is normally the thermodynamically highly unfavored form. While a few applications of LAB derivatives have appeared(9–11), there has been no report of the use of this unique AB in living cells. Importantly, LAB can be photoswitched in a chromatically independent way with UV and blue/green light(8, 10) to generate spectrally distinct chromophore that compare favorably with chromophores such as tetrafluoro(4F)AB(12) (Figure 1). Thus, we felt that these properties merited exploration of LAB-X photoprobes, where X = glutamate or quaternary ammonium (QA), using well-defined photophamacological properties from previous studies of other ABs(13–15). We found that conditions could be found when both cis LAB-Glu (2) and LAB-QA (3) did not target their ion channel receptors. Such derivatives disturbed the excellent trans photostationary state (PSS) of the parent LAB chromophore (ca. 50% compared to 85%(8, 16)), whilst preserving the 100% cis PSS, suggesting that simple photowswitchable drugs might not be able to exploit LAB’s unique properties fully. However, the ring substitution of LAB required to attach the pharmacophore produced the benefit of a bathochromic shift the absorption maximum of cis-LAB-X to the violet region, making such probes more compatible with use of visible light in both optical channels.

Figure1.

Comparison of LAB and 4FAB absorption spectra. Absorption spectra of cis-LAB (cyan) and trans-LAB (green) in hexane. The former is the pure cis configuration isolated from synthesis, and corresponds to the thermodynamically stable and green light photostationary state (PSS). The latter is abstracted from an HPLC chromatogram. Note that cis-LAB is transparent above 500 nm, a region where trans-LAB absorbs strongly. For comparison, the absorption spectra of 4FAB, also at its PSSs(18), are plotted, showing a similar but smaller separation of the nπ* absorption bands in the visible region.

Results.

Synthesis and photochemical properties of LAB-X probes.

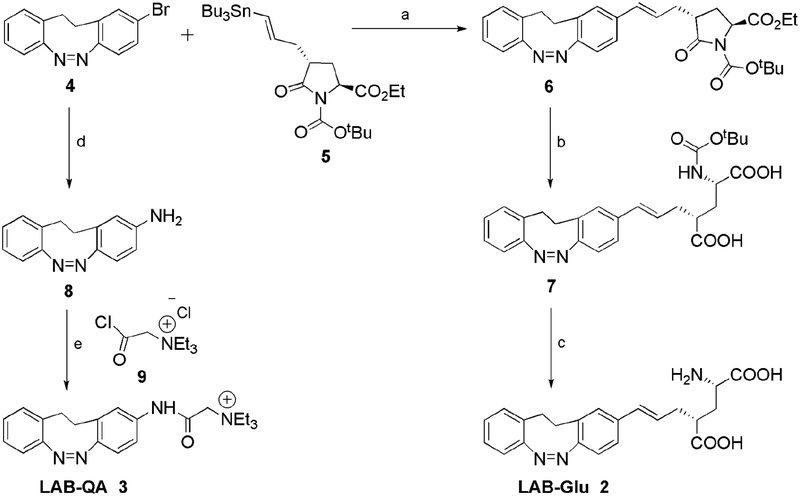

We synthesized LAB-Glu 2 and LAB-QA 3 based on LAB chromophore as outlined in Scheme 1. The stereoselective synthesis of 2 followed(15), and proceeded through palladium catalyzed Stille coupling of known(16) LAB-Br 4 with vinyl stannane 5 to give BOC protected LAB pyroglutamate 6 with 21% yield (Scheme 1). Hydrolysis with KOH and deprotection of BOC group by TFA yielded 2 as a dihydrate, trifluoroacetate salt in an overall 16% yield. LAB-QA was synthesized following(13) by coupling of LAB-amine 7 with known precursor 2-triethyl ammonium acetic acid chloride.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of LAB-X.

Reagents and conditions: a) Pd (PPh3)4, CuI, CSF, 21%; b) LiOH, H2O, THF, 80%; c) 3M HCl, EtOAc, RT, 1h, 16%; d) Benzophenone imine, Pd (OAc)2, BINAP, CsCO3, THF, 30%; e) DIPEA/DMF, 40% (counter ion not shown for clarity).

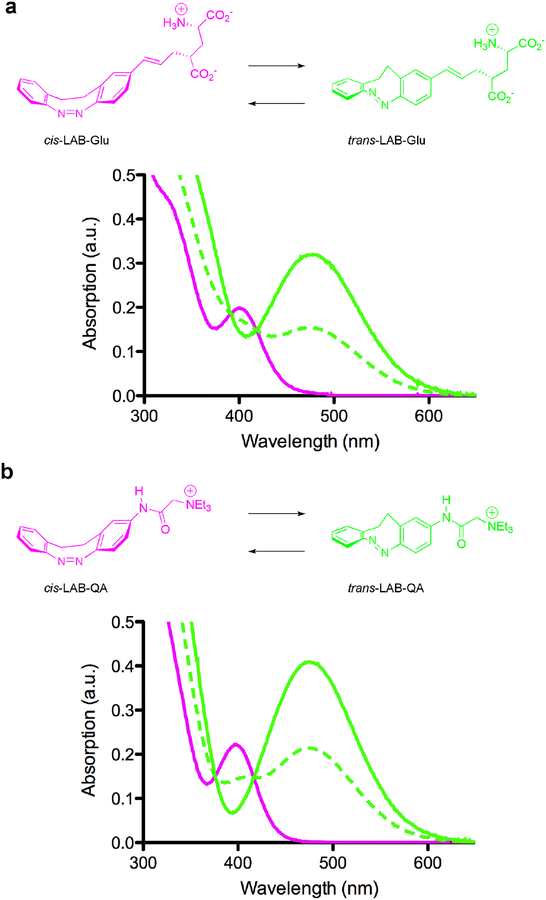

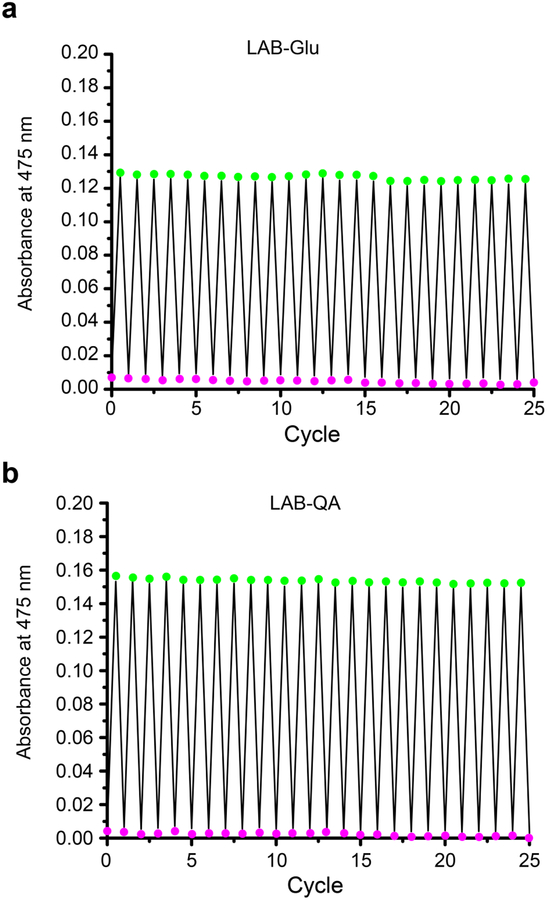

First, we evaluated the photoswitching properties of our LAB derivative 2 and 3. Both compounds were isolated in 100% cis configuration (Supporting Information Figure S1,2). The absorption spectra of these compounds are slightly red-shifted compared to the parent LAB chromophore(8), with λmax of 402 nm and 400 nm for LAB-Glu (Figure 2a) and LAB-QA (Figure 2b), respectively, for the nπ transitions. Illumination with a violet light (405-nm-LED) generated the trans configurations of 2 and 3 with the expected large bathochromic shift (ca. 70 nm) with λmax at 475nm (green dash for LAB-Glu Figure 2A and LAB-QA Figure 2b). HPLC analysis revealed these PSSs corresponded to 47% and 52% LAB-Glu and LAB-QA, respectively (Supporting Figure S1 and S2). Thus, simple substituents of the LAB chromophore lowered the reported trans-PSS (85–92%, (8, 16)). Never the less, the expected quantitative cis-PSS was achieved using green light (530-nm-LED) for both 2 and 3 (Supporting Figure S1 and S2). Both probes exhibited slow thermal relaxation of the trans configurations to the thermodynamically favored cis configurations in the dark, with a half-life times of 17.3 and 0.77 h for trans-LAB-Glu and LAB-QA, respectively (Supporting Information Figure S3). Finally, we tested the resistance to photofatigue of our new probes. We were unable to detect photodegradation using UV-vis absorption spectra after multiple switching with violet and green light (Figure 3). Having established that our LAB-X probes preserved many of the desirable properties of the parent LAB scaffold, we tested these photoswitches using living neurons in brains slices acutely isolated from mice.

Figure 2.

Spectra of LAB-X.

Spectra of pure cis configurations for LAB-Glu (a) or LAB-QA (b) isolated from synthesis (violet lines) in Hepes (pH 7.4). These spectra are identical to green PSS arising irradiation of trans-LAB-X. Absorption spectra of the PSS from 405 nm LED-irradiation are shown (green dashes). Calculated all trans spectra are shown for both probes (green lines). Calculated all trans spectra were obtained by subtracting spectra at the violet PSS from the pure cis spectra, then normalising these data from the PSSs determined by HPLC.

Figure 3.

Photoswitching of LAB-X without photofatigue.

Solutions of LAB-Glu (a) and LAB-QA (b) in Hepes (pH 7.4) could be irradiated with violet and green light through multiple cycles without any detectable photofatigue as monitored by absorption spectroscopy. Green and violet colors represent the trans and cis configurations, respectively. Photon fluxes: violet light, 107 mWcm−2 from a 405-nm LED; green light, 5.5 mWcm−2 from a 530-nm LED.

LAB-Glu – photoswitching of an extracellular ion channel agonist.

First, we tested pharmacology of both configurations of LAB-Glu at their PSSs to check if they could discriminate the binding affinity towards the glutamate receptor in neurons which are endogenously expressing ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) (Figure 4). Various concentrations of either cis-LAB-Glu (ranging from 50 to 250 μM) or trans-LAB-Glu (2.35 – 235 μM) were puffed into single hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons, and excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded in whole-cell voltage clamp mode. We were unable to detect any significant currents by cis-LAB-Glu up to a concentration of 0.25 μM (Figure 4a). Thus, cis-LAB-Glu functions just like caged glutamate at this concentration, being completely inert towards non-NMDA and NMDA receptors. These data provided a test bed for the assessment of trans-LAB-Glu using the violet PSS mixture of cis and trans configurations. In contrast, significant EPSCs were recorded with trans-LAB-Glu (EC50 value of ~0.075 μM, Supporting Information Figure S4a). The amplitude of the trans-mediated EPSCs increased with puffing duration (Figure 4b).

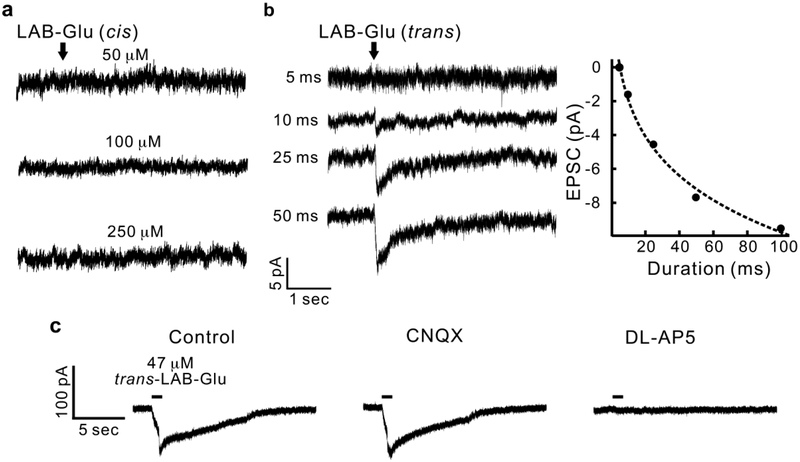

Figure 4.

Pharmacology of cis and trans-LAB-Glu.

a) Puffing cis-LAB-Glu to a hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron at different concentrations (0.05, 0.1, 0.25 mM) for 100 ms. b) Left: Puffing trans-LAB-Glu (0.047 mM, i.e. 0.1 mM LAB-Glu at the violet PSS) onto a CA1 pyramidal neuron for different durations (5, 10, 25, 50 ms). Right: Quantification of the relationship between trans-LAB-Glu evoked currents and puffing durations. c) The currents evoked by 1 sec puffing of trans-LAB-Glu (control) were blocked by DL-AP5 (40 μM), but not CNQX (10 μM), implying LAB-Glu activates NMDA receptors. All experiments were repeated in 3 cells.

We examined the currents in presence of various antagonists to test the subtype specificity of iGluRs towards LAB-Glu(Figure 4c). First, bath application of CNQX (10 μM), a non-NMDA antagonist (middle panel in Figure 4c), had no effect on EPSCs compared to the control (normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), left panel in Figure 4c). However, in presence of DL-AP5 (40 μM), a selective NMDA antagonist, blocked the evoked EPSC (right panel in Figure 4c). These results demonstrate that trans-LAB-Glu activates NMDA receptors selectively. We confirmed the NMDA receptor specificity by monitoring current-voltage relationship with or without Mg2+ after puffing trans-LAB-Glu (0.047 mM, Supporting Information Figure S4c). We found the J-shaped I-V curve in the presence of external Mg2+ and linear I-V curve in the absence of Mg2+, consistent with the NMDA receptors being partially blocked by extracellular Mg2+ at resting membrane potentials. These data are similar to those reported by DiGregorio and Trauner for a related AB-based probe(17) but slightly different from the original reversibly caged glutamate(15).

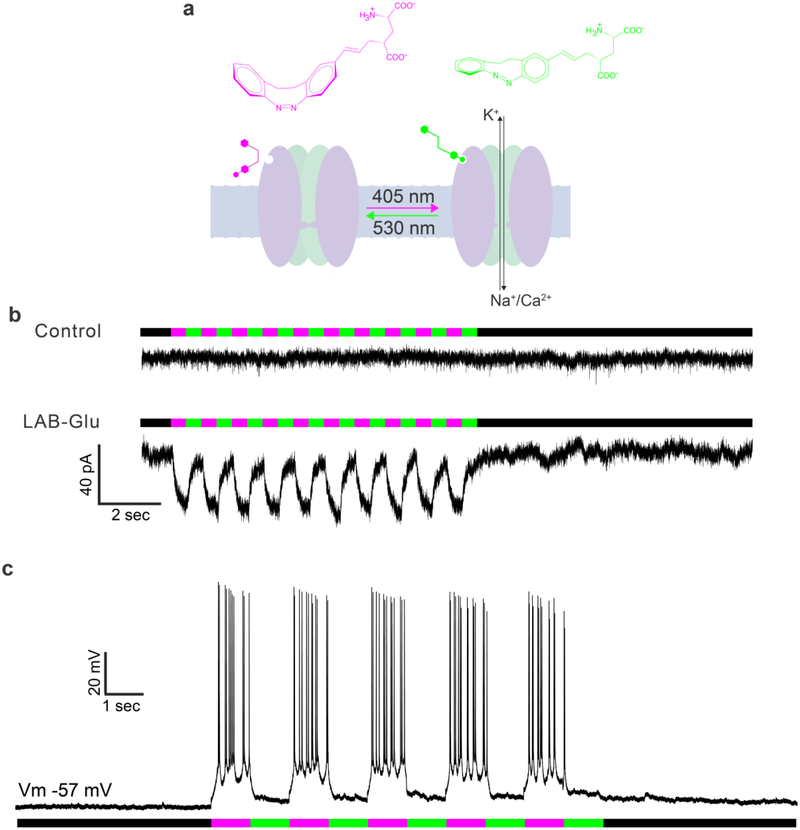

Having established the basic, stationary-state pharmacology of LAB-Glu, we evaluated the dynamic, bidirectional photochemical modulation of NMDA receptor mediated ion fluxes in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Figure 5). We used local perfusion of cis-LAB-Glu (0.1 mM, or ACSF as control) onto CA1 neurons. Irradiation with violet light (405-nm LED) induced significant EPSCs (35 ± 0.9 pA, n = 4 cells) from NMDA receptors (Figure 5b bottom) in comparison to control (Figure 5b top, n = 3 cells). These currents were quickly silenced by illumination with green light (530-nm LED, Figure 5b bottom). Furthermore, in whole-cell current-clamp mode, continuous local perfusion of cis-LAB-Glu (0.1 mM) did not trigger action potentials (Figure 5c), showing again the cis-configuration is biologically inert (Note that during this experiment, no current was injected to the neurons to prevent action potential firing). Irradiation with violet light (405-nm LED) triggered action potentials (Figure 5c), which were terminated with green light. In both voltage clamp and current clamp, such bidirectional manipulations of currents/potentials could be performed in succession, numerous times (Figure. 5). Thus, LAB-Glu could be useful to control the neural activity bidirectionally using two colors of visible light with chromatic independence.

Figure 5.

Photoswitching of LAB-Glu on CA1 neurons.

a) Cartoon illustrating how LAB-Glu binds to glutamate receptors and activates current flow. b) Currents evoked by bidirectional photoswitching of LAB-Glu. Control: puffing normal ACSF continuously, LAB-Glu: puffing of 0.1 mM cis-LAB-Glu continuously (n = 3 or 4 cells, control and LAB-Glu, respectively). c) Bidirectional photoswitch of action potentials by LAB-Glu (n = 3 cells).

LAB-QA - photoswitching of an intracellular ion channel pore blocker.

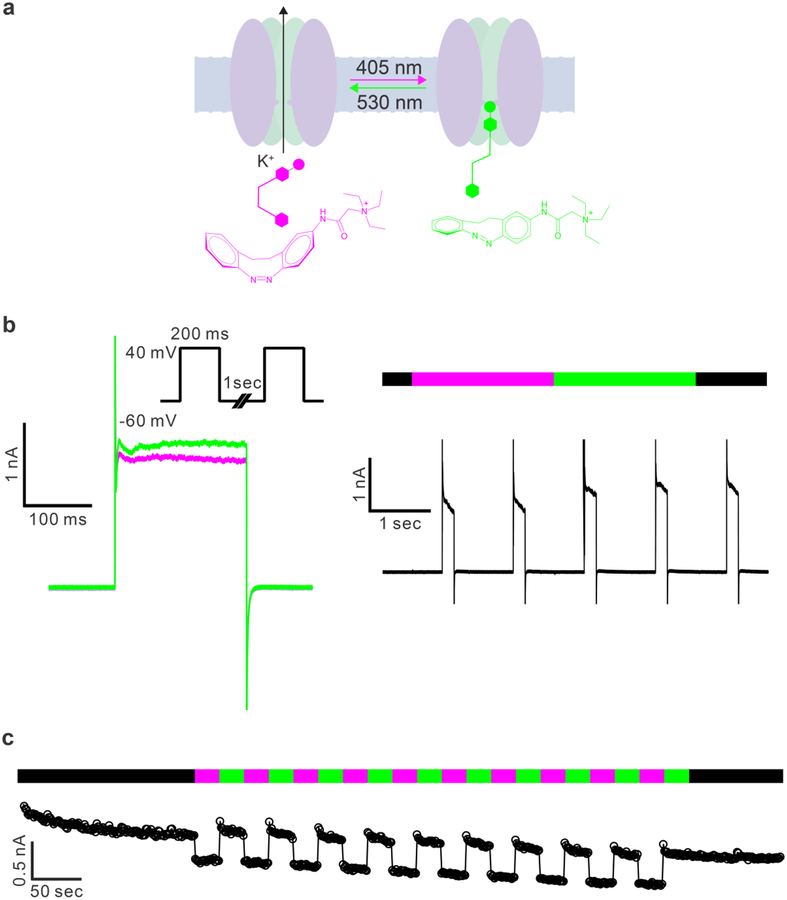

Having established the photochemical efficacy of LAB-Glu on neurons, we explored the utility of the LAB photoswitch scaffold to modulate ion channels intracellularly using LAB-QA (3). We used the well established paradigm that (photoswitchable) monomeric QA probes block open potassium channels from the inside in a use dependent way(13). We expected the more bulky cis configuration to have less access to the inner vestibule of the channel compare to the elongated trans form, the latter would therefore block potassium channel currents more effectively (Figure 6a). Thus, we filled single hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in an acutely isolated brain slice with LAB-QA (0.5 m) via the patch pipette. Voltage dependent currents evoked by step depolarization from −60 to +40 mV were monitored (Figure 6b). Irradiation with violet and green light resulted in reversible modulation of potassium current amplitudes (Figure 6b). The result indicated that, like 4FAB-QA(18), trans-LAB-QA blocked more effectively (1.3 ± 0.1 nA) (Figure 6b) the open channel ion than the cis counterpart (1.6 ± 0.1 nA). All cells were responded to light irradiation. The blocking efficacy was 18.8 ± 0.7 %, calculated as (currents in cis-isoform – currents in trans-isoform)/current in cis-isoform).

Figure 6.

Photoswitching of LAB-QA inside CA1 neurons.

a) Cartoon illustrating how LAB-QA binds to the inner vestibule of potassium channels in the trans configuration. b) Currents from a CA1 pyramidal neuron responding to voltage steps (−60 to +40 mV) with LAB-QA (0.5 mM) in patch recording pipette with violet and green light (left). Bidirectional modulation of voltage-gated ion channels with LAB-QA. The electrophysiological protocol consisted of depolarizing voltage steps from −60 mV to +40 mV for 200 ms at a frequency of 1 Hz. This depolarization activated voltage-gated potassium channels were reversible blocked by violet and green light (right). c) Multiple rounds photoswitching of LAB-QA inside a CA1 neuron. This is representative of traces obtained from 3 cells. Voltage steps as in b).

Finally, we tested the bidirectional photoswitching of LAB-QA, in CA1 pyramidal neurons during multiple rounds of illumination. LAB-QA (0.5 mM) was loaded into neurons by patch clamp recording pipette, and the currents were recorded with stepwise depolarizations of cells from −60 to +40 mV at frequency of 1Hz, illuminating with violet and green light sequentially at an interval of 26 s (Figure 6c). The result clearly demonstrated the reversible modulation of steady state potassium currents using multiple rounds of illumination, showing LAB-QA could be an excellent photoswitch to study Kv channels in neurons with low intensity visible light and high photostability.

Discussion.

Azobenzene (AB) and AB derivatives are the most widely studied photochromes(19). The effects of ortho and/or para substituents on the PSS and the rate of relaxation of the metastable cis configuration are profound(20, 21). In the current work we were very attracted by the basic photochemical properties of the LAB chromophore(8). Namely, that the PSS for cis and trans at 100% and 85–92%(8, 16), respectively, and that there is excellent chromatic separation of these two configurations (Figure 1). Absorption spectra of cis and trans configurations of normal AB have complete overlap in the visible range of 400–500 nm, the region used to drive cis to trans isomerization(13, 21, 22). In contrast, the spectral separation of the nπ* absorption bands of LAB is strikingly large (Figure 1). These seem quite similar, or perhaps even better than the 4FAB chromophore (Figure 1). Furthermore, unlike all other AB photochromes, LAB is uniquely more stable in its cis configuration(8). In this report we have explored the effects of ring substitution of the chromophoric properties of LAB, and tested if such probes can exploit the distinctive thermodynamic properties of this AB scaffold. We chose to make two probes with fundamentally different pharmacological targets in living neurons. LAB-Glu (2) was designed to modulate extracellular glutamate receptors(15), whereas LAB-QA (3) has intracellular binding site on voltage-gated potassium channels(13).

We found that when cis-LAB-Glu was applied to neurons at quite high concentrations (0.25 mM) no currents were detected, implying that the thermodynamically favored cis configuration was biologically inert. This pharmacology reproduces what one normally sees with the vast majority of AB-based bioprobes(1–3). Thus, the dark adapted LAB-Glu which naturally resides 100% is the cis form appears “like caged glutamate” for ionotropic glutamate receptors (Figure 3). However, the ring substitution used to create LAB-Glu from LAB subtly changes the absorption spectra, and the trans PSS. The former shows a favorable red shift with the absorption maxima of cis-LAB-Glu to 402 nm, a value that matches well with the standard violet lasers widely available on confocal microscopes (405 nm). However, the PSS is significantly reduced from the LAB scaffold value of 85–92%(8, 16) to 47%. It spite of this, we were able to use photolysis of cis-LAB-Glu to fire action potentials reversibly in CA1 neurons in brains with violet and green light (Figure 4).

Our results with LAB-QA were broadly similar to LAB-Glu. We found the violet PSS of LAB-QA was only 52%. This should be contrasted with those reported by Herges(23) and Woolley(10) for their diamido-LAB derivatives. In the former case, substituents were para to the methylene bridge, and gave 54% trans PSS, whereas in the latter para to the diazo allowed 70% trans PSS to be achieved. All of these values are lower than our recently developed 4FAB-QA, which has a violet PSS of 86%(18), a value similar to its parent diamido-4FAB scaffold(24). We suggest the decrease in trans-LAB might have important practical consequences for the use of the LAB scaffold under certain circumstances. Typically mono-QA photoprobes are bath applied to cells at low concentrations 25–100 μM for several mins to allow permeation across the plasma membrane(13). The bath solution is replaced with normal extracellular media before patch clamping with a normal intracellular solution. In the case of LAB-QA we found this strategy did not work (data not shown), and that relatively high concentrations (0.5 mM) were required in the patch pipette for effective photoswitching (Figure 5). Our data taken together suggest that whilst LAB-Glu and LAB-QA preserve many of the highly attractive photochemical properties of the parent chromophore, the slightly smaller change in molecular geometry for cis to trans LAB scaffold(8) compare to non-bridged AB molecules(7) probably reduces pharmacological efficacy of the active trans configuration of LAB-X tested here.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the thermal stabilities of our trans-LAB-X probes are changed compared to the parent trans-LAB scaffold(8). The latter is reported to have half-life of about 4.5 h in hexane, whereas LAB-Glu and LAB-QA were 17.3 and 0.77 h in aqueous buffer at RT.

So if one is to select a scaffold beyond “normal AB”(22, 25) for biological application, which derivative is to be preferred? Obviously a comprehensive summary is beyond the scope of this article. But we propose the following brief set of considerations for such planning. Our recent results suggest that if long-term thermal stability of the metastable trans configuration is a priority then 4FAB(12) is the scaffold of choice(18). If greater thermal stability of regular AB is desired, then dimethyl scaffolds seem highly promising(26). If one desires the use of longer wavelengths of visible light for photoswitching, then tetramethoxy-ABs work well(27, 28). Finally, some amino-ABs are very thermally unstable in the cis configuration, conferring useful photo/thermal control of biological processes(14, 29, 30). Additionally, synthetic flexibility and compatibility with other optical probes that might be used in biological applications are further considerations that go beyond the chemical properties of the azobenzene chromophore itself. In terms of tethered photoswitches(22), we envisage LAB being quite useful when it is required that the trans configuration pushes an attached pharmacophore into the binding cleft, since upon thermal or photochemical reversion the 100% cis form would then completely turn off the activated receptor.

Conclusions.

This is the first study of the ortho-bridged azobenzene (AB) photoswitchable scaffold (which we call locked-AB, or “LAB”) for controlling signaling in living cells. We found that, like the parent LAB chromophore(8), mono-substituted LAB-X probes preserve the 100% thermodynamic stability of cis configuration of the core LAB photoswitch. Importantly, ring substitution caused a subtle but useful bathochromic shift in the cis-LAB absorption maxima, allowing two colors of visible light (violet and green) to be used for multiple rounds of photoswitching in cuvette and in living cells. Hand in hand with this improvement of LAB with LAB-X, we found significant reduction in the trans photostationary state, implying that careful cost benefit analysis should be applied for uses of the unique LAB photoswitch scaffold in future applications.

METHODS

Synthesis and spectroscopic analysis

Details of synthesis are described in the Supporting Information. UV-Vis spectra were recorded using a Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Photostationary sate was determined by continuous illumination with either violet or green LED (M405L3, M530L3, Thorlabs, NJ, USA until no further change in the absorption spectra, and further cis-trans composition was determined by HPLC using the relative integrated areas of the cis and trans peaks at the isosbestic wavelength, considering the sum of integrated area for two peaks is 100%.

Animal and brain slices preparation

All animal studies were approved by Mount Sinai IACUC review. C57BL/6J mice (8–12 weeks.) were anaesthetized with isoflurane and the brain was quickly removed. Horizontal slice sections (350 μm) were then made in ice-cold cutting solution containing (in mM): 60 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 7 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 100 sucrose, 3 sodium pyruvate, 1.3 sodium ascorbate equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.3–7.4). The brain slices were then incubated for 15 min at 33°C in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1MgCl2, 2CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 sodium pyruvate, 1.3 sodium ascorbate; 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.3–7.4). After incubation, all brain slices were held in ACSF at room temperature > 1 hour before patch clamp recording.

Patch clamp recording and photostimulation

Brain slices were transferred to the submerged chamber of a BX-61 microscope (Olympus, Penn Valley, PA, USA) and perfused with ACSF (in mM: 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.3–7.4) at room temperature. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons were visualized with a 60X objective (Olympus) and infrared differential interference contrast optics. Whole-cell recordings were made with an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA Instruments, Bellmore, NY, USA) in voltage-clamp mode (Vm holding at −60 mV) or current-clamp mode. The electrical signals were recorded at 20 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz with Pulse (HEKA). Recording pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution (in mM: 135 potassium gluconate, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2-ATP, 0.4 Na2-GTP, 10 Na2-phosphocreatine, pH 7.35). Voltage-gated sodium channel blocker TTX (1 μM) was present in ACSF during voltage clamp recordings in LAB-Glu experiments. Glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX (10 μM) and DL-AP5 (100 μM) and the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (20 μM) were added to ACSF during recording voltage-dependent currents in LAB-QA experiments.

A violet and green LED (405 and 530 nm, respectively; Thorlabs, NJ, USA) were mounted on the epifluorescence port of the microscope and light beams were combined and directed to the objective by standard long-pass dichroic mirrors. Light power was controlled via the LED driver (LEDD1B, Thorlabs) by external voltage modulation. Timing and duration of LED lights were controlled by TTL signals and synchronized with EPC-10 system.

Data analysis and statistics

The amplitudes of LAB-Glu evoked currents were calculated as the difference of the peak and baseline. The amplitudes of Kv currents were calculated as the difference of the steady state and baseline. In the figure of long term multiple photoswitches of LAB-QA, each point represents as the mean amplitudes of 12 Kv current steps. All data were expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH to G.C.R.E-D.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting figures and experimental procedures, and general experimental details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Conflicts of interest.

None.

References.

- 1.Beharry AA, and Woolley GA (2011) Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules, Chem Soc Rev 40, 4422–4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szymanski W, Beierle JM, Kistemaker HA, Velema WA, and Feringa BL (2013) Reversible photocontrol of biological systems by the incorporation of molecular photoswitches, Chem Rev 113, 6114–6178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fehrentz T, Schönberger M, and Trauner D (2011) Optochemical genetics, Angew Chem Int Ed 50, 12156–12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gostl R, Senf A, and Hecht S (2014) Remote-controlling chemical reactions by light: Towards chemistry with high spatio-temporal resolution, Chemical Society Reviews 43, 1982–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman H, Vratsanos SM, and Erlanger BF (1968) Photoregulation of an enzymic process by means of a light-sensitive ligand, Science 162, 1487–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velema WA, Szymanski W, and Feringa BL (2012) Photopharmacology: beyond proof of principle, J Am Chem Soc 136, 2178–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandara HM, and Burdette SC (2012) Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene, Chem Soc Rev 41, 1809–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siewertsen R, Neumann H, Buchheim-Stehn B, Herges R, Nather C, Renth F, and Temps F (2009) Highly efficient reversible Z-E photoisomerization of a bridged azobenzene with visible light through resolved S(1)(n pi*) absorption bands, J Am Chem Soc 131, 15594–15595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eljabu F, Dhruval J, and Yan H (2015) Incorporation of cyclic azobenzene into oligodeoxynucleotides for the photo-regulation of DNA hybridization, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 25, 5594–5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samanta S, Qin C, Lough AJ, and Woolley GA (2012) Bidirectional photocontrol of peptide conformation with a bridged azobenzene derivative, Angew Chem 51, 6452–6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Han G, and Zhang W (2018) Concise Synthesis of Photoresponsive Polyureas Containing Bridged Azobenzenes as Visible-Light-Driven Actuators and Reversible Photopatterning, Macromolecules 51, 4290–4297. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleger D, Schwarz J, Brouwer AM, and Hecht S (2012) o-Fluoroazobenzenes as readily synthesized photoswitches offering nearly quantitative two-way isomerization with visible light, J Am Chem Soc 134, 20597–20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banghart MR, Mourot A, Fortin DL, Yao JZ, Kramer RH, and Trauner D (2009) Photochromic blockers of voltage-gated potassium channels, Angew Chem 48, 9097–9101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mourot A, Kienzler MA, Banghart MR, Fehrentz T, Huber FM, Stein M, Kramer RH, and Trauner D (2011) Tuning photochromic ion channel blockers, ACS Chem Neurosci 2, 536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volgraf M, Gorostiza P, Szobota S, Helix MR, Isacoff EY, and Trauner D (2007) Reversibly caged glutamate: a photochromic agonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors, J Am Chem Soc 129, 260–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun M, Joshi DK, Yalagala RS, Vanloon J, Simionescu R, Lough AJ, Gordon HL, and Yan H (2018) Confirmation of the Structure of Trans-Cyclic Azobenzene by X-Ray Crystallography and Spectroscopic Characterization of Cyclic Azobenzene Analogs, Chemistryselect 3, 2697–2701. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laprell L, Repak E, Franckevicius V, Hartrampf F, Terhag J, Hollmann M, Sumser M, Rebola N, DiGregorio DA, and Trauner D (2015) Optical control of NMDA receptors with a diffusible photoswitch, Nat Commun 6, 8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passlick S, Richers MT, and Ellis-Davies GCR (2018) Thermodynamically Stable, Photoreversible Pharmacology in Neurons with One- and Two-Photon Excitation, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 57, 12554–12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baroncini M, Ragazzon G, Silvi S, Venturi M, and Credi A (2015) The eternal youth of azobenzene: new photoactive molecular and supramolecular devices, Pure Appl. Chem . 87, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pozhidaeva N, Cormier M, Chaudhari A, and Woolley G (2004) Reversible photocontrol of peptide helix content: Adjusting thermal stability of the cis state, Bioconjugate Chem 15, 1297–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tochitsky I, Banghart MR, Mourot A, Yao JZ, Gaub B, Kramer RH, and Trauner D (2012) Optochemical control of genetically engineered neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, Nat Chem 4, 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banghart M, Borges K, Isacoff E, Trauner D, and Kramer RH (2004) Light-activated ion channels for remote control of neuronal firing, Nat Neurosci 7, 1381–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sell H, Nather C, and Herges R (2013) Amino-substituted diazocines as pincer-type photochromic switches, Beilstein J Org Chem 9, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knie C, Utecht M, Zhao F, Kulla H, Kovalenko S, Brouwer AM, Saalfrank P, Hecht S, and Bleger D (2014) ortho-Fluoroazobenzenes: visible light switches with very long-Lived Z isomers, Chemistry, Eur. J 20, 16492–16501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumita J, Smart O, and Woolley G (2000) Photo-control of helix content in a short peptide, P Natl Acad Sci Usa 97, 3803–3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin WC, Tsai MC, Rajappa R, and Kramer RH (2018) Design of a Highly Bistable Photoswitchable Tethered Ligand for Rapid and Sustained Manipulation of Neurotransmission, J Am Chem Soc 140, 7445–7448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong M, Babalhavaeji A, Samanta S, Beharry AA, and Woolley GA (2015) Red-Shifting Azobenzene Photoswitches for in Vivo Use, Acc Chem Res 48, 2662–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beharry AA, Sadovski O, and Woolley GA (2011) Azobenzene photoswitching without ultraviolet light, J Am Chem Soc 133, 19684–19687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kienzler MA, Reiner A, Trautman E, Yoo S, Trauner D, and Isacoff EY (2013) A red-shifted, fast-relaxing azobenzene photoswitch for visible light control of an ionotropic glutamate receptor, J Am Chem Soc 135, 17683–17686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izquierdo-Serra M, Gascon-Moya M, Hirtz JJ, Pittolo S, Poskanzer KE, Ferrer E, Alibes R, Busque F, Yuste R, Hernando J, and Gorostiza P (2014) Two-photon neuronal and astrocytic stimulation with azobenzene-based photoswitches, J Am Chem Soc 136, 8693–8701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.