Abstract

Despite agreement that snacks contribute significant energy to children’s diets, evidence of the effects of snacks on health, especially in children, is weak. Some of the lack of consistent evidence may be due to a non-standardized definition of snacks. Understanding how caregivers of preschool-aged children conceptualize and define child snacks could provide valuable insights on epidemiological findings, targets for anticipatory guidance, and prevention efforts. Participants were 59 ethnically-diverse (White, Hispanic, and African American), low-income urban caregivers of children age 3 to 5 years. Each caregiver completed a 60–90 minute semi-structured in-depth interview to elicit their definitions of child snacks. Data were coded by two trained coders using theoretically-guided emergent coding techniques to derive key dimensions of caregivers’ child snack definitions. Five interrelated dimensions of a child snack definition were identified: (1) types of food, (2) portion size, (3) time, (4) location, and (5) purpose. Based on these dimensions, an empirically-derived definition of caregivers’ perceptions of child snacks is offered: A small portion of food that is given in-between meals, frequently with an intention of reducing or preventing hunger until the next mealtime. These findings suggest interrelated dimensions that capture the types of foods and eating episodes that are defined as snacks. Child nutrition studies and interventions that include a focus on child snacks should consider using an a priori multi-dimensional definition of child snacks.

Keywords: Children, snack, definition, schemas, qualitative

Introduction

Over the past 25 years there has been a consistent increase in the frequency of snacking by US children with the largest increases in salty snacks and candy (Piernas & Popkin, 2010). Many practitioners encourage healthy snacks among preschool-aged children (Hayman et al., 2004). Many caregivers, however, present children with energy-dense snacks that are high in saturated fat, which can contribute to overweight and obesity (Gregori, Foltran, Ghidina, & Berchialla, 2011). Further, children in low-income urban settings typically have fewer options for accessing healthy foods (Borradaile et al., 2009). For example, Kumanyika & Grier (2006) found that ethnic minority children in low-income households have higher rates of obesity and live in environments that promote unhealthy snacking behaviors. Despite agreement by researchers that snacks contribute significant energy to children’s diets (Miller, Benelam, Stanner, & Buttriss, 2013; Piernas & Popkin, 2010), evidence of the effects of snacks on health, especially in children, is inadequate. Some of the lack of consistent evidence may be due to a non-standardized definition of snacks (Gregori et al., 2011).

An eating episode is a bounded eating event or series of events that is defined using multiple related conceptual dimensions (Bisogni et al., 2007). What constitutes a meal, or different kinds of meals, has been studied extensively by researchers across cultures and contexts (Christine E. Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Jastran, & Devine, 2008; Douglas, 1972; Mintz & Bois, 2002; Murcott, 1982; Pliner & Zec, 2007; Wadhera & Capaldi, 2012; Wansink, Payne, & Shimizu, 2010). However, what constitutes a snack, has been less clearly defined within the field (Gregori & Maffeis, 2007; Wansink et al., 2010). Many nutritional epidemiology studies lack a standardized definition of snacks. In such studies, snacks are typically defined using researcher-defined lists of “snack foods”, self-defined eating occasions by participants, or as a tally of the number of daily eating occasions that occur outside typical meal times (Chamontin, Pretzer, & Booth, 2003; Gregori et al., 2011; Gregori & Maffeis, 2007; G. H. Johnson & Anderson, 2010a; Kirk, 2000; Nicklas et al., 2004; Piernas & Popkin, 2010). Particularly problematic is the use of a food-based snack definition that does not include any consideration of whether caregivers providing these foods would consistently consider the foods snacks across all contexts. These definitions may not accurately reflect the ways that caregivers, who are often responsible for providing snacks to young children, actually conceptualize and define snacks. Eliciting a definition of child snacks from caregivers’ perspectives could provide valuable insights on eating socialization, targets for anticipatory guidance, and prevention interventions. Targets for anticipatory guidance refer to areas in which physicians might provide input to caregivers regarding the behaviors of their child. For example, such targets might include guidance on current nutritional recommendations for children’s snacks. A definition of snacks is needed, however, to describe the specific foods, eating episodes, contexts, and behaviors that might be addressed in such guidance. Therefore, it is crucial that practitioners give caregivers of preschool-aged children concrete and consistent information regarding healthy snacks for their children.

This study employed qualitative methods to examine definitions of snacks among a diverse sample of low-income urban caregivers of preschool-aged children. This work is primarily informed by an eating episodes framework (Bisogni et al., 2007; C.E. Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Devine, & Jastran, 2007) and schema theory, which posits that cognitive information is organized in categories for quick recall to guide behavior in familiar settings (C. Blake & Bisogni, 2003; C.E. Blake et al., 2007; Rice, 1980). Results of the qualitative analysis were used to develop an empirically-based definition of snacking based on perspectives of caregivers of preschool aged children. Elucidating caregivers’ definitions of child snacks is critical for being able to talk with caregivers in ways that resonate with the way they think about and approach feeding their children.

Methods

Design

The study team employed a qualitative design to characterize low-income urban caregivers’ definitions of snacks offered to preschool-aged children. The data were part of a larger study designed to elucidate caregivers’ cognitive schemas and caregiving practices around child snacking. In the larger study, a series of card sorting tasks were used to elicit caregiver perceptions of snacks. Semi-structured open-ended questions were used throughout the interview to obtain caregiver descriptions of snacks and practices used to feed children snacks. The current study focuses on a subset of three questions from the semi-structured interview protocol that focused on caregiver definitions of child snacks.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants included 59 ethnically and racially diverse (White n=16, Hispanic n=20, and African American n=23), low-income caregivers of children age 3 to 5 years living in Boston, Massachusetts and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania who reported primary responsibility for feeding their child most of the time. The sample was predominantly female (55 participants) with a mean age of 31 years old. Further details of the complete sample are presented in table 1. Participants were recruited from urban Philadelphia and the Greater Boston Area using flyers posted in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) offices and online community listings such as craigslist.com. Exclusion criteria included being younger than 18 years and having a preschooler with severe food allergy, chronic medical condition, or developmental disorder that influenced feeding. Participants provided informed consent and were assured of confidentiality by research staff. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Temple University and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Participants were provided $45 in compensation for their time.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of caregivers (n=59)

| Sex | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 55 | 93.3 |

| Male | 4 | 6.7 |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 31.2 | 8.4 |

| Relationship to child | ||

| Mother | 54 | 91.7 |

| Other | 5 | 8.3 |

| Race/ | ||

| ethnicity | ||

| White | 16 | 28.3 |

| African American | 23 | 38.3 |

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | 20 | 33.3 |

| Primary language(s) spoken | ||

| Only/mostly English | 44 | 75.0 |

| Both English and Spanish equally | 3 | 5.0 |

| Only/mostly Spanish | 12 | 20.0 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 10 | 15.0 |

| High school graduate/GED | 18 | 31.7 |

| Technical school/some college | 23 | 38.3 |

| College graduate or greater | 8 | 15.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed | 19 | 35.2 |

| Self employed | 3 | 5.6 |

| Out of work less than 1 year | 14 | 25.9 |

| Out of work 1 year or more | 13 | 25.9 |

| Other | 4 | 7.4 |

| Full-time student | ||

| Yes | 19 | 33.3 |

| No | 40 | 66.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or living with partner | 23 | 38.3 |

| Divorced/separated | 5 | 8.3 |

| Single | 31 | 53.3 |

| Weight status* | ||

| Underweight | 2 | 3.3 |

| Normal weight | 16 | 28.3 |

| Overweight | 11 | 18.3 |

| Obese | 30 | 50.0 |

| Experienced food insecurity in past 12 months | ||

| Yes | 25 | 43.3 |

| No | 34 | 56.7 |

| Participated in assistance programs | ||

| WIC | 41 | 70.0 |

| Food Stamps/SNAP/EBT | 47 | 80.0 |

| Free/reduced school meals | 27 | 46.7 |

| Head Start | 20 | 35.0 |

| Number of children in household (mean, SD) | 2 | 1.0 |

GED, General Education Development; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; EBT, Electronic Benefit Transfer.

Weight status based on body mass index.

Procedures

Participants completed a 60–90 min individual interview in English or Spanish with a trained research assistant in a research setting. An expert in qualitative methods trained five research assistants (one of which was English-Spanish bilingual) during a two-day workshop in qualitative methods including card sort procedures and semi-structured interviewing techniques. All interviewers utilized a semi-structured interview guide with scripted procedures. Reflecting the goals of the larger study, interview guide questions focused on (a) caregivers’ definitions of snacks, (b) how caregivers decided when, where, and how much snack their child eats, and (c) how caregivers responded when their child pestered or nagged for a snack. The data presented in this study reflect caregivers’ responses to the initial question, “When I say the word snack, what do you think of”, and two follow-up questions: “How is a snack different than a meal?’ and “Can a drink be a snack?” Following the interview, participants completed a brief questionnaire, assessing demographic characteristics and food insecurity, which was defined as a lack of “access by all people at all times to have enough food for an active, healthy life” (Bruening, MacLehose, Loth, Story, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2012; Coleman-Jensen & Nord, 2013; Hager et al., 2010). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and later verified by the interviewer for accuracy. To facilitate data analysis, interviewers completed field notes immediately after each interview that included a description of the setting and other observations not captured directly through the interview.

Data analysis

Interview data were analyzed by the researchers using NVivo 10 qualitative analysis software package (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2012). The coding of the data used a theoretical framework that drew from schema theory (Rice, 1980) and eating episodes (Bisogni et al., 2007; C.E. Blake et al., 2007). This theoretical framework guided the emergent coding of the transcripts through a focus on the dimensions of participants’ child snack definitions. For example, a transcript statement such as, “[a snack] is like… something on the road, you give them…a little snack before they get home. But it’s not like a big meal”, viewed through the above-described theoretical frames, presents a definition of snacks that includes different dimensions including location and size. Codes were derived emergently from the transcribed interviews and two trained researchers qualitatively analyzed the passages that focused on participants’ definitions of child snacks. The analysis was guided by a grounded theory approach to data analysis (Charmaz, 2014) using the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 2009). Two trained researchers coded the transcripts, with one researcher acting as primary coder and the other as secondary coder. Coding by the research team progressed via the following steps: (1) The transcript passages were organized by interview question, (2) 50% of the transcripts were open-coded by the primary coder to identify general themes, (3) the open-coding was checked by the secondary coder for agreement on themes used and passages applied to each theme, (4) the primary coder open-coded the remaining 50% of the transcripts, (5) axial coding was conducted to identify relationships among the open codes, and (6) selective coding was conducted to identify core themes present in the transcript data around caregivers’ perspectives on child snacking. During steps 2–6, monthly meetings were held between the primary and secondary coder to verify the coding until all transcripts had been coded and organized into dimensions. From the dimensions, the research team constructed a definition of child snacks that represented the perspectives of participants.

Results

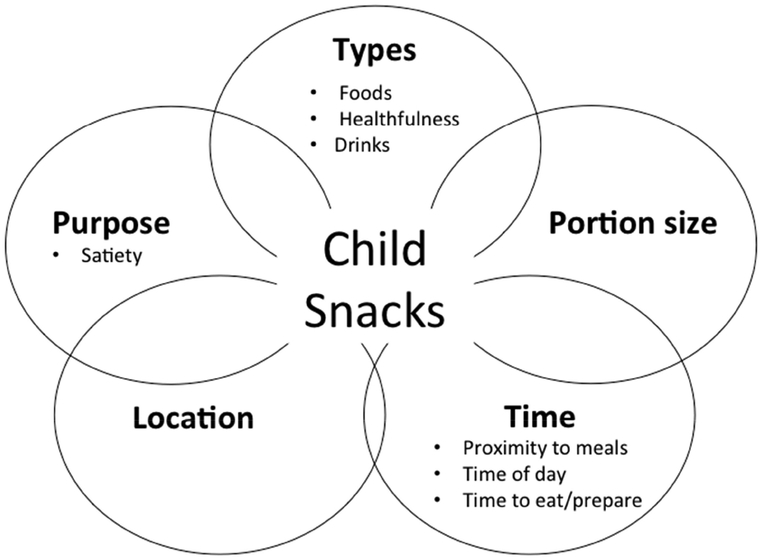

The research team identified five interrelated dimensions of participants’ child snack definitions: (1) types of food, (2) portion size, (3) time, (4) location, and (5) purpose. The following sections provide a description of these dimensions followed by a provisional definition of child snacks constructed from these dimensions.

Dimensions

Types

Well more than three quarters of the participants’ definitions of snacks included the types of foods their children consumed as snacks. After each participant was asked, “When I say the word ‘snack’ what do you think of?” they typically free-listed foods that they considered snacks. Free-listed foods fell into the following five food groups: fruits (e.g. apples, bananas, canned fruit, grapes, mangoes, oranges, and watermelon), vegetables (e.g. carrots and celery), baked goods (e.g. donuts, sweet breads, and toast), cookies and crackers, and dairy (e.g. ice cream, milk, cheese).

After each participant was asked, “When I say the word ‘snack’ what do you think of?” they were asked a follow-up question about whether they considered drinks as snacks for their child. Most participants, when first presented with this question, said they did not consider drinks to be snacks. However, some participants then qualified their response by adding that drinks could potentially be snacks if they were substantial in some way such as being perceived of as filling or high in sugar. In particular, some participants described offering sugar-sweetened beverages (such as juice or soda) to their children between meals but did not consider the beverages snacks. Some participants indicated that “yes” drinks could be defined as snacks but struggled to identify which beverages might qualify. For example one participant said, “Um, you know, like fruit juice or, um, like a smoothie [could be a snack]. Or… yeah, something like that. Or even water I guess. You know what I mean? Like not- don’t know if I really consider water like a big snack or anything”. For participants that included drinks in their snack definitions, common examples were juice, milk, and smoothies. The statement from the participant above and the somewhat contradictory description of drinks as “not snacks” reveals a lack of clarity around the concept of what a snack is and points to the potentially important role contexts and purposes might play in an individual’s determination of whether a given food or drink could be a snack. For example, if the purpose of giving a beverage was to sate a child’s hunger during an impromptu family outing, then that beverage might be considered a snack when it would have otherwise been considered simply a drink at home during a usual day.

Participants also identified the perceived healthfulness of foods as a defining characteristic of a snack. Participants did not commonly assess healthfulness by describing specific nutritional qualities like number of calories; rather they discussed healthfulness in more categorical terms such as healthy, unhealthy, or junk foods. One participant described what she saw as the wide range of snack foods encompassing both healthy and unhealthy or junk foods. She stated, “It’s weird, ‘cause you think of both [healthy and not healthy]. You think of junk food. You think of chips, popcorn, and then you also think of fruit, peanut butter, peanuts, and stuff like that. I typically try to lean towards the healthy side, but there’s times when you go to the corner store and grab a little 35 cent bag of chips and a quart of juice, water, or whatever that crap is, and then you call it a day. But usually I would say fruit”.

Portion Size

About half of the participants identified portion size as a dimension of their snack definition. For these participants, portion sizes were a defining factor as to whether a food was considered to be a snack or not. Participants provided statements such as “not a lot”, “a little portion”, or “a small amount of something” when talking about a specific food. For example, one participant said that a snack was, “lesser portions, not as big of a portion. Usually a meal, there’s vegetables or a meat or potatoes. For me, a snack is usually just one little portion of something”.

Time

Over half of the participants discussed the dimension of time. This was described in three ways: (1) proximity to meals, (2) the time of day in which the eating occurred, and (3) the time required to prepare or eat the food.

Proximity to meals was the most frequently discussed sub-dimension of time. Participants conceptualized snacks as occurring outside other eating episodes, like meals. One participant stated, “what makes something a snack? It would be kinda a small portion. It wouldn’t be the normal times of you know breakfast, lunch, and dinner; it would be in between. It could be, you know, when they’re watching TV or you know just doing different things. So, it’s not the normal routine, it’s in between”.

Participants also defined snacks in relation to the specific times of day when snacks were given. For instance one participant defined snacks as, “it’s in the afternoon, after a meal. I give him his snack…in the afternoon, that’s it’. Another participant, in defining the word snack stated, “snacks are only given once a day”.

Participants also presented the amount of time it took to prepare or eat a snack as a defining characteristic. In such statements, participants cited quickness or short amounts of time required to prepare snacks. One participant felt that snacks were quick foods that did not need to be prepared when she stated that, “a snack is something fast, on the go. Versus a meal, I guess, something prepared or cooked”. Another participant described a snack as “something that’s quick, small, and tastes good.” Another participant said that snacks were, “anything that I don’t have to cook”. Time required to consume a food was also a sub-dimension of time used to define snacks. Participants described a snack as something that their child could very quickly eat. For example, one participant described a snack as “a 1,2,3 gobble down thing”.

Location

Around one quarter of the participants identified the importance of location, typically oriented in relation to the home, in their definition of snacks for their child. Snacks were generally discussed in reference to whether the snack episode occurred inside versus outside the home. Within the home, participants cited eating locations that would serve to define the episode as a snack versus a meal. For example, one participant felt that meal eating could only occur at the table in the kitchen, and might involve members of the family, but snacks could occur anywhere in the house and might be a more individualized event. She stated, “snacking, I let her do pretty much wherever in the house, I guess. She can sit on the couch and watch her shows and have a snack or I’ll bring in her room sometimes and but mealtime is we sit down at the table and that’s kind of the difference there for us, I guess.” This conception was echoed by another participant who stated, “Snack is different from a meal because, you know, they can sit in front of the TV and eat a snack. But rather than when I feed ‘em their meal, they got to stay at the table, no TV on, no pencil and paper at the table”.

Purpose

Over half of the participants defined snacks by citing the purpose of the eating episode. Snacks for satiety was a common dimension in the definition of child snacks. Participants described satiety in two different ways in their definition of snacks: (1) curbing hunger, referred to consistently as “tide over” or “hold over” until the next meal and (2) snacks as foods that are less filling than meals. According to participants who defined snacks by their purpose, the function of a snack was to reduce hunger but not completely remove it. Several participants cited that snack foods, then, were “something light”. Participants discussed “light” foods in terms of their ability to reduce, but not remove, hunger rather than the foods being “light” in the nutritional sense. For example, one participant described snacks as, “something small that you would eat between meals to kind of tide you over”. Another defined snacks by saying, “it’s something light, maybe to hold me over to the next meal”. Likewise, another participant stated, “a snack is something you just grab, something light to go and a meal is just like four courses, real heavy’. A third participant echoed this statement, adding in the concept of holding over. She defines a snack as “something light to hold you over for your main course”.

A few participants defined snacks by contrasting them to similar eating episodes they referred to as treats or rewards. For example, one participant said, “I think of healthy choices - as far as snacking goes. Um, we use kind of two words in my house. There’s snack and then there’s treat. So treats would be maybe, you know, more sugary kind of cookies and things like that and snacking in my house is usually we go for, you know, I give a few choices, healthy choices”.

A caregiver-based provisional definition of child snacking

Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework reflecting the five dimensions of caregivers’ child snacks definitions: (1) types of food, (2) portion size, (3) time, (4) location, and (5) purposes. These five dimensions reflect a definition of snacks wherein “snack” foods were selected by caregivers and offered to children at certain times, in certain locations, and to achieve satiety. From these themes, an empirically-based definition of child snacks from low-income caregivers’ perspectives can be summarized as follows:

Figure 1.

Figure showing five interrelated dimensions of caregivers’ definition of child snacks

A small portion of food that is given in-between meals, frequently with an intention of reducing or preventing hunger until the next mealtime.

Discussion

The definition of child snacks in this paper expands on previous definitions (Gregori et. al., 2011), that emphasize characteristics of food (e.g. quality and composition) and time (e.g. foods given outside of normal meal times) as consistent features of a snack by adding location, satiety, and purpose as key interrelated dimensions in a snack definition. Our findings point to the unique cognitive positioning that snacks hold for caregivers of young children compared to other eating episodes like meals (e.g., dinner or lunch) or treats. We found that the liminal, or in-between, nature of snacks provides boundaries for the definition of a snack.

The portion size of a given food appeared to play a role in caregivers’ determinations of whether or not a food was considered a snack. Participants indicated that snacks were often defined by their small portion sizes. As discussed in a more detailed investigation into the role of portion sizes of child snacks (Blake et al., 2014), portioning strategies are an important feature of caregiver snack planning for their children. It has been shown that low-income mothers’ determinations of “appropriate” mealtime portion sizes for their young children are partially based on observations of their children’s prior eating experiences (S. L. Johnson, Goodell, Williams, Power, & Hughes, 2015). Since “the right amount” may be a subjective determination based on each individual child, it is likely that the portion sizes that define an eating episode as a snack will vary among caregivers. This variation between caregivers’ portion size assessments and episode definitions (e.g., meal versus snack) may present challenges in researchers’ attempts to create lists of snack foods with standardized portion sizes for use in dietary assessment.

In this study, child snacks were frequently defined in contrast to meals; snacks were frequently described in terms of their capacity to reduce hunger until the next meal as well as being less filling than meals. Since snacks may be less consistently defined than meals, foods offered to children as snacks may not mentally register in the assessment of foods given to their children and therefore parents may not report them as snacks in assessments. Further, being more tightly defined, meals might be more beholden to regulated performed actions, such as eating dinner at a table in a designated room. Definitions of snacks appear to be more variable than meals, making the definition of a snack contingent on proximity to meals and other contextual factors, such as the location where a food is or is not eaten or the purpose for giving food. Relatively less clearly defined conceptualizations of snacks, then, might not necessarily be consistently coupled with locations in the same way that meals are. Practically, this means that a food eaten in one place, time, or for one purpose will be called a snack but the same food eaten in another time, place or for another purpose will be defined as something other than snack.

Interestingly, some participants distinguished between snacks and treats, yet it is known that caregivers frequently give snacks as rewards or for other behavioral reasons (Davison et al., 2015). For some participants, a treat episode differed from but was closely related to a snack episode, where the description of a treat or reward was used referentially to define snacks through juxtaposition. Further, for these participants, treats were typically defined as being unhealthy. The bifurcation of foods into “healthy” and “unhealthy” might provide a way for some caregivers who emphasize health in their food choices to distinguish snacks from other closely related eating episodes, like treats. This is consistent with findings that nutritive and non-nutritive purposes influence adults feeding practices for their children (Herman, Malhotra, Wright, Fisher, & Whitaker, 2012) and indicates that such purposes may also undergird how eating episodes are cognitively classified.

The research team employed a qualitative grounded theory analytic approach based on existing theory to investigate child snack definitions held by low-income, urban caregivers. We recruited a large sample (n=59) (Morse, 2000) of racially and ethnically diverse participants across two sites. These features provided a wide range of participant perspectives and allowed for an in-depth analysis of snack definitions. However, because of our exclusive focus on low-income urban caregivers, generalizability may be limited to these demographic groups. Further, we were not able to recruit many fathers into the study and, as such, our sample is 93% female and this may have affected the generalizability of the findings presented. Findings from this study have not been tested empirically and may benefit from follow-up research and refinement.

Conclusions

Over the last quarter century there has been an increase in the consumption of unhealthy snacks in children (Piernas & Popkin, 2010). Yet, due to a lack of a cohesive definition of child snacks in the literature, the dietary effects of this increase are difficult to fully or consistently understand or assess. A cohesive, theoretically-oriented, emergent snack definition is needed for translatable measurement and assessment across studies (Gregori & Maffeis, 2007). The findings of this study suggest that individuals’ definitions of snacks are based on the interrelated dimensions of types of food, time, location, portion size, and the purpose for giving a snack. It is important for dietary recalls to prompt participants for a range of purposes (e.g., tiding over) and contexts (e.g., different locations in the home where eating might occur) so as to fully capture all foods consumed and to properly label these episodes to reflect participants’ definitions. It may also be beneficial to explicitly probe foods that could be used for nonnutritive purposes, such as for treats or rewards, to minimize under-reporting. While previous analyses have identified common characteristics of what constitutes a snack in various studies (Gregori et al., 2011), these were done post hoc. It is important to measure and assess snacks, especially in children, as snacks’ effects on children’s health can be beneficial or detrimental, contributing to the increase or reduction of risk for overweight and obesity in children depending on their nutritional value (Keast, Nicklas, & O’Neil, 2010; Zizza, Tayie, & Lino, 2007).

This study provides formative information that may have practical implications for the development of family interventions promoting healthy snacks in children. Further, consideration of contextually-influenced perceptions of whether foods are considered snacks by caregivers is important and it may be valuable for interventions to consider the role of external factors (such as environment) that influence snack choice and which foods are considered snacks. By including a cohesive definition of child snacks in the development of research studies there is potential for more reliable accounting of the dietary effects of snacks on the diets of children. Likewise, using a consistent definition of snack episodes in the development of targeted interventions may increase their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

This study and publication was supported by Grant R21 HD074554 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bisogni CA, Falk LW, Madore E, Blake CE, Jastran M, Sobal J, & Devine CM (2007). Dimensions of everyday eating and drinking episodes. Appetite, 48(2), 218–231. 10.1016/j.appet.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake C, & Bisogni CA (2003). Personal and family food choice schemas of rural women in upstate New York. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 35(6), 282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Devine CM, & Jastran M (2007). Classifying foods in contexts: How adults categorize foods for different eating settings. Appetite, 49(2), 500–510. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.appet.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Jastran M, & Devine CM (2008). How adults construct evening meals. Scripts for food choice. Appetite, 51(3), 654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Fisher JO, Ganter C, Younginer N, Orloski A, Blaine RE, … Davison KK (2014). A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions and use of portion size strategies for preschool children’s snacks. Appetite. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666314005182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borradaile KE, Sherman S, Vander Veur SS, McCoy T, Sandoval B, Nachmani J, … Foster GD (2009). Snacking in children: the role of urban corner stores. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruening M, MacLehose R, Loth K, Story M, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2012). Feeding a family in a recession: Food insecurity among Minnesota parents. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruss MB, Morris JR, Dannison LL, Orbe MP, Quitugua JA, & Palacios RT (2005). Food, Culture, and Family: Exploring the Coordinated Management of Meaning Regarding Childhood Obesity. Health Communication, 18(2), 155–175. 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamontin A, Pretzer G, & Booth DA (2003). Ambiguity of “snack”in British usage. Appetite, 41(1), 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A, & Nord M (2013). Definitions of Food Security. United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks DL (2003). Trading Nutrition for Education: Nutritional Status and the Sale of Snack Foods in an Eastern Kentucky School. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 17(2), 182–199. 10.1525/maq.2003.17.2.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Blake CE, Blaine RE, Younginer NA, Orloski A, Hamtil HA, … Fisher JO (2015). Parenting around child snacking: development of a theoretically-guided, empirically informed conceptual model. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 109 10.1186/s12966-015-0268-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M (1972). Deciphering a meal. Daedalus, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Duffey KJ, & Popkin BM (2011). Energy Density, Portion Size, and Eating Occasions: Contributions to Increased Energy Intake in the United States, 19772006. PLoS Med, 8(6), e1001050 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten IH, & Razi S (2009). The Effects of Cultural Familiarity on Reading Comprehension. Reading in a Foreign Language, 21(1), 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Transaction Publishers; Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=rtiNK68Xt08C&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=strauss+and+glaser&ots=UVvSVi1KYJ&sig=ty9Yf1BJtByH7JmwZHZscsY-sPI [Google Scholar]

- Gregori D, Foltran F, Ghidina M, & Berchialla P (2011). Understanding the influence of the snack definition on the association between snacking and obesity: a review. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 62(3), 270–275. 10.3109/09637486.2010.530597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori D, & Maffeis C (2007). Snacking and Obesity: Urgency of a Definition to Explore such a Relationship. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(4), 562 10.1016/j.jada.2007.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst WB (2005). Theorizing About Intercultural Communication. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, Coleman SM, Heeren T, Rose-Jacobs R, … others. (2010). Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics, 126(1), e26–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman LL, Williams CL, Daniels SR, Steinberger J, Paridon S, Dennison BA, & McCrindle BW (2004). Cardiovascular Health Promotion in the Schools A Statement for Health and Education Professionals and Child Health Advocates From the Committee on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in Youth (AHOY) of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation, 110(15), 2266–2275. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141117.85384.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AN, Malhotra K, Wright G, Fisher JO, & Whitaker RC (2012). A qualitative study of the aspirations and challenges of low-income mothers in feeding their preschool-aged children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 9(1), 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman JD (2006). Food and memory. Annu. Rev. Anthropol, 35, 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GH, & Anderson GH (2010a). Snacking definitions: impact on interpretation of the literature and dietary recommendations. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 50(9), 848–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GH, & Anderson GH (2010b). Snacking Definitions: Impact on Interpretation of the Literature and Dietary Recommendations. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 50(9), 848–871. 10.1080/10408390903572479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Goodell LS, Williams K, Power TG, & Hughes SO (2015). Getting my child to eat the right amount. Mothers’ considerations when deciding how much food to offer their child at a meal. Appetite, 88, 24–32. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.appet.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keast DR, Nicklas TA, & O’Neil CE (2010). Snacking is associated with reduced risk of overweight and reduced abdominal obesity in adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(2), 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk TR (2000). Role of dietary carbohydrate and frequent eating in body-weight control. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 59(03), 349–358. 10.1017/S0029665100000409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, & Grier S (2006). Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. The Future of Children, 16(1), 187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennernäs M, & Andersson I (1999). Food-based classification of eating episodes (FBCE). Appetite, 32(1), 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R, Benelam B, Stanner SA, & Buttriss JL (2013). Is snacking good or bad for health: An overview. Nutrition Bulletin, 38(3), 302–322. 10.1111/nbu.12042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz SW, & Du Bois CM. (2002). The Anthropology of Food and Eating. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31(1), 99–119. 10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.032702.131011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murcott A (1982). The cultural significance of food and eating. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 41(02), 203–210. 10.1079/PNS19820031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas TA, Morales M, Linares A, Yang S-J, Baranowski T, De Moor C, & Berenson G (2004). Children’s meal patterns have changed over a 21-year period: the Bogalusa heart study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104(5), 753–761. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.jada.2004.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piernas C, & Popkin BM (2010). Trends In Snacking Among U.S. Children. Health Affairs, 29(3), 398–404. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, & Zec D (2007). Meal schemas during a preload decrease subsequent eating. Appetite, 48(3), 278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 10).

- Rice GE (1980). on cultural schemata. American Ethnologist, 7(1), 152–171. 10.1525/ae.1980.7.1.02a00090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhera D, & Capaldi ED (2012). Categorization of foods as “snack” and “meal” by college students. Appetite, 58(3), 882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Payne CR, & Shimizu M (2010). “Is this a meal or snack?” Situational cues that drive perceptions. Appetite, 54(1), 214–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizza CA, Tayie FA, & Lino M (2007). Benefits of snacking in older Americans. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(5), 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]