Abstract

Background.

The strong link between dopamine and motor learning has been well-established in the animal literature with similar findings reported in healthy adults and the elderly.

Objective.

We aimed to conduct the first, to our knowledge, systematic review of the literature on the evidence for the effects of dopaminergic medications or genetic variations in dopamine transmission on motor recovery or learning after a nonprogressive neurological injury.

Methods.

A PubMed search was conducted up until April 2018 for all English articles including participants with nonprogressive neurological injury such as cerebral palsy, stroke, spinal cord injury, and traumatic brain injury; quantitative motor outcomes; and assessments of the dopaminergic system or medications.

Results.

The search yielded 237 articles, from which we identified 26 articles meeting all inclusion/exclusion criteria. The vast majority of articles were related to the use of levodopa poststroke; however, several studies assessed the effects of different medications and/or were on individuals with traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury or cerebral palsy.

Conclusions.

The evidence suggests that a brain injury can decrease dopamine transmission and that levodopa may have a positive effect on motor outcomes poststroke, although evidence is not conclusive or consistent. Individual variations in genes related to dopamine transmission may also influence the response to motor skill training during neurorehabilitation and the extent to which dopaminergic medications or interventions can augment that response. More rigorous safety and efficacy studies of levodopa and dopaminergic medications in stroke and particularly other neurological injuries including genetic analyses are warranted.

Keywords: levodopa, dopamine agonists, neurological rehabilitation, genetic variation

Introduction

Optimizing motor recovery is a major rehabilitation goal after stroke, cerebral palsy (CP), and other neurological injuries that affect motor functioning. Intensive motor training of the upper limbs has been shown to be effective in many with stroke and CP,1,2 with lower limb outcomes less consistently positive.3,4 Importantly, the degree of motor recovery from even the more effective interventions is often variable and modest, warranting continued exploration of alternatives5 and of individual factors that best explain response variability.6

The role of the dopamine system in motor skill learning is well recognized and has been the focus of many studies in animals as well as several with healthy adults.7,8 Projections from the dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area directly to the primary motor cortex (M1) have been found to be particularly important. A series of studies showed that lesioning dopaminergic terminals in the forelimb region of M1 in rats or lesioning the dopaminergic pathways from the ventral tegmental nucleus in the midbrain to M1, prevented them from learning a reach-and-grasp task, whereas learning was preserved in the sham surgical group and the group in which the noradrenergic terminals were selectively lesioned. As further proof, injecting levodopa into M1 of those whose dopamine terminals were lesioned restored their ability to learn.9,10 They further showed that rats that learned the reaching task before the brain lesions were still able to perform the task, indicating that these dopaminergic terminals are important for motor learning but not execution of an already learned task.9,10 The role of dopamine during early development was investigated in another study on healthy newborn rats that received injections of levodopa which demonstrated that they learned to swim better and faster than controls, while rats with selective dopaminergic lesions showed delayed development of swimming.8 Furthermore, rats with M1 lesions demonstrated spontaneous improvement of forelimb function; however, injection of a dopamine antagonist into the striatum prevented this recovery, pointing to the potential importance of dopamine in spontaneous recovery from brain injury.11 The dorsal striatum, which includes the caudate and putamen nuclei of the basal ganglia, is a major target of dopaminergic projections from neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and these pathways are also highly related to motor functioning. Other studies have explored the effects of variations in dopamine gene expression by comparing learning in 2 inbred strains of mice that differ markedly in the number of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Qian et al12 demonstrated that learning but not execution of motor tasks was impaired in the strain that exhibited overexpression compared with normal expression of dopamine genes, in this case revealing that too much dopamine, similarly to too little dopamine, can also impair learning.12

Studies with healthy older adults have corroborated animal data and provided evidence that the dopamine system is important in motor learning and the formation of motor memories in humans. Normal aging is associated with a decline in dopamine functioning and the ability to form motor memories.13 Floel et al14 found that supplementing brain dopamine with levodopa in healthy, elderly subjects increased memory encoding of a novel motor task. The degree of motor memory formation was correlated with increases in dopamine release in the dorsal caudate nucleus. A single dose of levodopa increased the rate at which young adults were able to learn a new motor task and helped older adults recover their ability to form a motor memory to levels seen in the younger subjects.5 These results suggest that ameliorating declines in dopamine functioning can improve the ability to form motor memories and enhance the effectiveness of motor training.

In contrast, a recent randomized trial by Pearson-Fuhrhop et al15 investigating whether motor skill training effects could be augmented by levodopa versus placebo in healthy adults found no mean group differences in learning. The researchers further evaluated whether individual differences in dopamine transmission genes had influenced their study results. Genes of interest included catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1), DRD2, and DRD3, and the dopamine transporter gene (DAT) all involved in the regulation of dopamine levels in synapses and dopamine neurotransmission within the brain, including brain structures important to motor learning.15 A gene score was calculated for each participant from 0 to 5 based on polymorphisms of COMT, DRD1–3, and DAT in which a higher score indicated polymorphisms that enhanced dopamine transmission. Those with higher gene scores had better learning only with placebo but were made worse if given additional dopamine. Conversely, those with lower gene scores learned poorly on placebo but fared better with levodopa, indicating that only those with decreased dopamine responded positively to medication. This finding has high clinical relevance because it provides evidence that responses to motor skill training as well as the effects of dopaminergic medications can differ across individuals due to natural variations in dopamine genes.

More recently, studies have emerged demonstrating that experimentally induced traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) in rodents can negatively affect dopaminergic functioning. Chen et al16 found that experimental lesions resulted in a significant decrease in striatal dopamine release, an effect that was more pronounced in the severe injury group. Consistent with the known role of the striatum in procedural learning and other aspects of cognitive functioning, decreases in striatal dopamine release were significantly correlated with deficits in motor performance in the severe group and with deficits in cognitive performance in both the mild and severe groups.16 Administration of dopamine agonists aripiprazole and methylphenidate after experimental TBI resulted in greater motor and cognitive performance improvements than in vehicle-treated rats17,18 although gender associations with responses to injury and to medication were observed.18 Rats treated with aripiprazole also had significantly less hippocampal neuronal loss and smaller cortical lesions than vehicle-treated rats.17 These studies provide evidence that brain injuries may disrupt brain dopamine systems, adversely affecting both motor and cognitive performance, and that dopaminergic medications may mitigate these declines.

Based on the accumulating evidence on the effect of specific dopamine pathways, genes, or medications on improvement in or recovery of motor learning in animals and in healthy adults, we decided to perform a review of the existing literature on the role of dopamine on motor recovery and training in children and adults with non-progressive neurological injuries. Our specific questions were: (1) what evidence is there to support the hypothesis that medications or other interventions aiming to increase dopamine transmission can enhance motor recovery in those with neurological injuries and (2) what evidence is there to demonstrate that alterations in genes involved in dopamine transmission are related to individual variation in recovery or treatment responses to interventions aiming to increase dopamine levels in the brain?

Methods

Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted in PubMed. Key words were (dopamine OR dopaminergic OR levodopa) AND (motor skills OR motor cortex OR motor neurons OR motor activity OR motor control OR motor learning OR motor function OR motor development OR motor recovery OR movement) AND (non-progressive brain injury OR cerebral palsy OR stroke OR traumatic brain injury). All studies published in English before April 2018 were included.

Selection Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if (1) participants had a nonprogressive neurological injury such as CP, stroke, traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury; (2) quantitative motor outcomes were included; and (3) the dopaminergic system or the effects of dopaminergic interventions were assessed. Animal studies and literatures reviews were excluded as were studies that involved progressive neurological disorders, focused on neglect, involuntary movements or akinetic mutism, or did not present data or use quantitative measures.

Selection Process

After the initial search was compiled and duplicates removed, 2 reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved publications. Full-text versions of remaining articles were obtained and reviewed independently by both authors to determine if they met all eligibility criteria. References listed in review articles and all included articles were screened and included if they met eligibility criteria. Differences in opinion were resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Study design, diagnosis, sample size, demographic information (age and sex), time since injury, intervention type, secondary interventions, length of follow-up, outcome variables, and results were extracted from each manuscript and are presented in Table 1 (intervention studies) and Table 2 (association studies). For the intervention studies, Sackett’s levels 1 to 5 of evidence were assigned to each.19 Also, we followed current Cochrane Collaboration recommendations not to use quality rating scales for study appraisal but instead used their risk of bias tool for all randomized studies.20

Table 1.

Data Extracted From Reviewed Intervention Studies.

| Study | Study Design | Dx | n | Sex | Mean Age, Years (Range or SD) | Time Since Injury, Months (Range or SD) | Intervention (Dosage) | Intervention Length | Co-interventions | Outcome Variables | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acler (2009)27 | RSPC | Stroke | 12 | 5 F | 7 M | 70 (8) | 10–28 | LDOPA (25–100 mg/day) | 5 weeks | PT in 2 and 5 weeks | RMA, 9-HPT, TMS, 10-meter walk | Levodopa group better than placebo on 9-HPT and 10-meter walk test. Cortical silent period longer in levodopa group and correlated with 9-HPT; unchanged in placebo group. |

| Brunstrom (2000)45 | CR | CP | 1 | 1 F | 16 | N/A | LDOPA (100–200 mg/d) | 2 weeks (continuing) | ADL, kinematics and EMG during ball reach task | Patient improved on ball reach task in ability to maintain static arm position; co-contraction decreased in 5/6 muscles during task. Functional improvements also reported. | ||

| Cramer (2009)38 | RDP | Stroke | 33 | 10 F | 23 M | 61.5 (14) | 7 (3.5) | Ropinirole (0.25–4 g/day); PT | 9 weeks | PT 60 min gait and 30 min arm training 2×/wk × 4 weeks | SIS-16, FM, BI, gait velocity, and endurance | No significant differences between the ropinirole and placebo groups on any measure. |

| Crisostomo (1988)32 | RDP | Stroke | 8 | 1 F | 7 M | 60.7 (47–73) | 6.5 days (3 −10 days) | AMPH (10 mg); PT | 1 day (1 dose) | One 45-min session of active paretic arm use | FM | Dextroamphetamine group had significantly greater improvements than placebo on FM. |

| Floel (2005)25 | RDPC | Stroke | 9 | 3 F | 6 M | 66.1 (9.5) | 44.4 (8.4) | LDOPA (100 mg); motor training task | 1 day (1 dose) | Thumb motor training two 30-min sessions | Motor training task outcome | Levodopa group performed better than placebo on motor training task. |

| Gorgoraptis (2012)39 | RDPC | Stroke | 16 | 2 F | 14 M | 58 (14) | 18 (21) | Rotigotine (4 mg/d) | 7–11 days | Motricity Index, Box and Blocks, 10-meter walk, grip and pinch dynamometry, 9-HPT | No significant differences between rotigotine and placebo groups on any measure. | |

| Grade (1998)34 | RDP | Stroke | 21 | 10 F | 11 M | 71.3 (3.6) | 18.3 days (3.7 days) | MPH (5–60 mg/d) | 3 weeks | Inpatient rehabilitation daily up to 3 weeks | FM, modified FM | Methylphenidate group significantly higher than placebo on modified FIM, positive trend for FM. |

| Kakuda (2011)28 | CR | Stroke | 5 | 2 F | 3 M | 61 (56–66) | 64 (18–143) | LDOPA (100 mg/d); OT and TMS | 7 weeks LDOPA; 15 days OT/TMS | One session motor training per condition | MAS, FM, WMFT | All improved on FM and WMFT. 3/5 patients improved on MAS (no statistical analyses). |

| Koeda (1998)41 | CR | TBI | 1 | 1 F | 9.3 | 22 | LDOPA (50–200 mg/d) | 3 months (continuing) | ADL | Patient had decreased rigidity and improvement in rolling over, maintaining sitting position, and walking on knees. | ||

| Lal (1998)40 | CR | TBI | 12 | N/A | 27.1 (17–54 | 16.9 (3.7–5.2) | LDOPA (300–1000 mg/d) | 3–24 months (some continuing) | ADL | All showed improvements in mobility, and 9/11 patients became more independent. | ||

| Lokk (2011)31 | RDP | Stroke | 78 | 30 F | 48 M | 64 (9.8) | 2.2 (1.1) | LDOPA (125 mg/d) and/ or MPH (20 mg/d); PT | 3 weeks | NDT: basic functional mobility, sensory, cognitive training 45 min × 5 days × 3 weeks | FM, BI, NIHSS | Levodopa and methylphenidate group showed significantly greater improvements than placebo between baseline and 6 months on the NIHSS and BI. |

| Maric (2008)46 | RDPC | SCI | 12 | 4 F | 8 M | 50.9 (23–72) | 1.9 (1–4) | LDOPA (200 mg/d); PT | 6 weeks | PT 2×/day for 30–45 min on functional training; robotic locomotor training when able 45 min 5 day/wk | ASIA motor score, WISCI-II, SCIM-II | No significant differences between levodopa and placebo groups on any measure. |

| Radhakrishna (2017)47 | RDP | SCI | 45 | 5 F | 39 M | 40 (20–62) | 12.4 years (2.5 years) | LDOPA (100–750 mg) and/ or buspirone (10–75 mg) | 1 day (1 dose) | EMG activity from 8 muscles | 8/25 patients receiving levodopa and buspirone showed significant changes in EMG activity. No patients receiving placebo, levodopa or buspirone alone, had significant changes in EMG activity. | |

| Restemeyer (2007)24 | RDPC | Stroke | 10 | 6 F | 4 M | 62 (12) | 58 (9 months to 20 years) | LDOPA (100 mg); PT | 1 day (1 dose) | Paretic arm dexterity training for two 60-min sessions | 9-HPT, TMS, ARAT, hand grip dynamometry | No differences between levodopa and placebo groups on any measure. |

| Rosenthal (1972)44 | CR/DP | CP | 9 | 8 F | 1 M | 31 (10.9) | N/A | LDOPA (0.5–2 g) | 4–12 months (some continuing) | Coordination/dexterity tasks, SCMAT, ADL, APMTB | 5/7 improved in handwriting, 6/7 in motor function, 3/3 in SCMAT, 3/3 in Ayres Perceptual Motor Test Battery, 6/6 in walking, 6/9 in sitting posture, and 5/9 in ADL. | |

| Rosser (2008)26 | RDPC | Stroke | 18 | 5 F | 13 M | 66.4 (6.8) | 40 (25) | LDOPA (150 mg/d) | 2 days | One session of procedural motor training | FTT, SRTT | Levodopa group performed better than placebo on SRTT. |

| Samuel (2017)29 | RS | Stroke | 8 | 1 F | 7 M | 63.3 (39–72) | 8.5 days (5–12 days) | LDOPA (100 mg/d); OT, PT, VR-based motivational visuomotor feedback training | 2 weeks | 1 hour PT/OT for all + 30 min VR or 30 min conventional PT × 2 weeks | FM, ARAT, kinematic measures | Levodopa and VR group improved more than levodopa PT control group on both FM and ARAT. |

| Scheidtmann (2001)23 | RDP | Stroke | 47 | 21 F | 26 M | 62.3 (11.3) | 1.4 (0.9) | LDOPA (100 mg/d); PT | 3 weeks | Inpatient PT for 6 weeks (3 with drug) | RMA | Levodopa group had significantly greater improvements than placebo on RMA; improved walking ability and upper extremity function faster and better. |

| Shiller (1999)42 | CR | TBI | 1 | 1 M | 18 | 15 years | Amantadine (200–300 mg/d); PT | 6 weeks | “Comprehensive rehabilitation” | Fine and gross motor movements, ADL | Patient had clinically significant improvement in bed-towheelchair transfer time, but slight nonsignificant improvements in time to put shirt on and propel wheelchair 75 feet | |

| Sonde (2007)30 | RDP | Stroke | 25 | 13 F | 12 M | 77.6 (65–91) | 8 days (7.6–9.3 days) | LDOPA (50–100 mg/d), and/ or AMPH (10–20 mg/d); PT | 2 weeks | Balance, transfer and functional motor training 5×/week × 2 weeks | FM, BI, ADL | No significant group differences. |

| Tardy (2006)36 | RDPC | Stroke | 8 | 8 M | 60 (46–70) | 18.8 days (9–35 days) | MPH (20 mg); motor training task | 1 day (1 dose) | NIHSS, BI, FTT, MAS, fMRI, Hand grip dynamometry, trunk control test, target pursuit task | Compared with placebo, methylphenidate group demonstrated a significant improvement on FTT, and hyperactivation of the ipsilateral primary sensorimotor cortex correlated with FTT scores. | ||

| Walker-Batson (1995)33 | RDP | Stroke | 10 | 6 F | 4 M | 64.5 (48–73) | 22.8 days (16–30 days) | AMPH (10 mg/ session); PT | 10 sessions, 1 session every 4 days | Practiced Fugl-Meyer Tasks for 10 sessions | FM | Dextroamphetamine group improved significantly compared with placebo on FM at 1-week and 12-month follow-up. |

| Wang (2014)35 | RSP | Stroke | 9 | 2 F | 7 M | 52.9 (11.9) | ≤ 1 | MPH (20 mg); tDCS | 1 day (1 dose) | Inpatient rehabilitation | TMS, Purdue Pegboard Test | Combination treatment (methylphenidate and tDCS) produced significantly greater improvement on Purdue Pegboard Test than tDCS or methylphenidate alone. |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; SD, standard deviation; Dx, diagnosis; R, randomized; S, single-blind; D, double-blind; P, placebo-controlled; C, crossover; CR, case report; FM, Fugl-Meyer Assessment; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; RMA, Rivermead Motor Assessment; BI, Barthal Index; 9-HPT, 9-hole peg test; RMI, Rivermead Mobility Index; ADL, activities of daily living; NEADL, Nottingham Extended ADL Scale; MAS, Motor Assessment Scale; WMFT, Wolf Motor Function Test; ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; FTT, finger tapping test; SRTT, Serial Reaction Time Task; mRS-Up, modified Rankin score-up; APMTB, A.J. Ayres Perceptual Motor Test Battery; SCMAT, Southern California Motor Accuracy Test; WISCI-II, Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II; SCIM-II, Spinal Cord Independence Measure II; SIS-16, Stroke Impact Scale 16; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association score; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; EMG, electromyography; PT, physical therapy; OT, occupational therapy; LDOPA, levodopa; AMPH, dextroamphetamine; MPH, methylphenidate; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Table 2.

Data Extracted From Reviewed Association Studies.

| Study | Study Design | Dx | n | Sex | Mean Age, Years (Range or SD) | Time Since Injury | Genes Assessed | Length of Follow-up | Co-interventions | Outcome Variables | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaz-Heijtz (2018)51 | Cohort | CP | 33 | 12 F | 21 M | 2.2 (1.5–5) | N/A | COMT, DAT, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3 | 2-month drug intervention | CIMT 2 h/d × 2 months | AHA, genome analysis | Higher combined gene score associated with greater change in AHA score after CIMT |

| Kim (2016)49 | Cohort | Stroke | 74 | 32 F | 42 M | 61.4 (14.1) | 1 week | COMT, DRD1, DRD2, DRD3 | 6 months poststroke | Inpatient rehabilitation | FM, FIM, NIHSS, genome analysis | Those with Met(−) polymorphism on COMT gene had higher FM and FIM scores than Met(+) group at discharge, and 3 and 6 months postinjury |

| Liepert (2013)50 | Cohort | Stroke | 83 | 30 F | 53 M | 68.7 | 19 days (7 COMT days to 3 months) | 6 months poststroke | Inpatient rehabilitation | RMA, BI, genome analysis | Those with Met/Met polymorphism were worse on RMA and BI than those with Val/Val, with performance in Val/ Met group between the other two. | |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; SD, standard deviation; Dx, diagnosis; CP, cerebral palsy; COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; DAT, dopamine transporter, DRD1–3, dopamine receptor D1-D3; AHA, Assisting Hand Assessment; FM, Fugl-Meyer Assessment; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; RMA, Rivermead Motor Assessment; BI, Barthal Index; CIMT, Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy; Met, methionine; Val, valine.

Authors reviewed guidelines for assessing the level of evidence and the risk of bias together, then performed each process separately, with differences in opinion resolved through discussion. This review was further constructed in accordance with the PRISMA statement and guidelines, a set of evidence-based criteria for reporting in systematic reviews.21

Results

Selected Studies

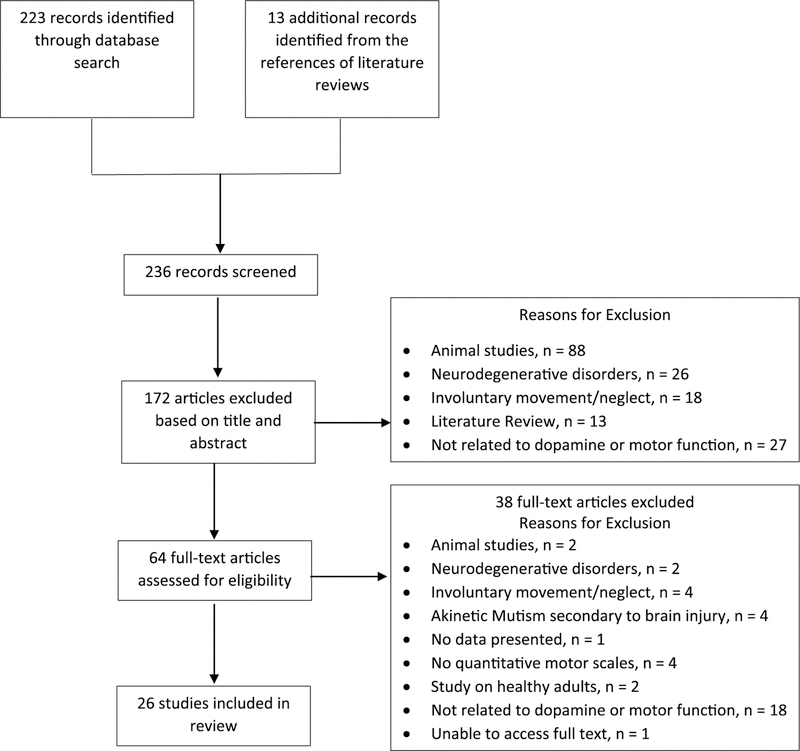

The literature search produced 223 articles, 172 of which were excluded based on title and abstract. After reviewing the full text of the 51 remaining articles, 13 were determined to meet all inclusion/exclusion criteria. Screening the references of literature reviews and included articles yielded another 13 relevant articles, bringing the total number of included articles to 26. One publication only described a study protocol.22 The authors were contacted and informed us that the results are only available as a conference abstract; therefore, we did not include these results in our review. The selection process of studies is outlined in more detail in Figure 1. Each study and the relevant details are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Table 3 shows the levels of evidence and the Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials20 for the randomized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 17). Only 2 RCTs met the criteria for level 1b,23,31 with the rest designated as level 2b. The remaining clinical studies (n = 6) were case reports, each assigned a Sackett’s level of 4, all with an inherent serious risk of bias due to subject selection, among other factors, or genetic correlational/association studies (n = 3). Intervention studies will be discussed by type of medication within a condition.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection process.

Table 3.

Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment and Sackett’s Levels of Evidence.a

|

The cells are shaded as follows: white, low risk of bias; gray, unclear risk of bias; black, high risk of bias.

Levodopa and Stroke

Most identified studies focused on the use of levodopa in stroke. Length of intervention and time since injury varied drastically across studies with treatment courses ranging from a single dose to a 7-week trial and initiated from as soon as 5 days to 20 years after injury. Trials evaluating the effects of up to 3 doses of levodopa had conflicting results. In a randomized, crossover trial, Restemeyer et al24 administered single doses of levodopa or placebo to patients nine months to 20 years poststroke. No significant differences between drug and placebo were found on motor function or on transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the paretic upper extremity. On the other hand, Floel et al25 found that after a single dose of levodopa, patients between 1 and 8 years poststroke performed significantly better on a simple motor task compared to placebo. They concluded that levodopa enhanced patients’ ability to encode a motor memory. Rosser et al26 tested the effects of levodopa on procedural motor learning through the serial reaction time task (SRTT) where participants unconsciously learn a sequence through repetitively pressing keys in response to visual cues. In this crossover study, patients performed the SRTT after randomly receiving 3 doses of levodopa or placebo over a 24-hour period. While on levodopa, participants had significantly better SRTT performance compared to placebo, suggesting that levodopa modulated motor learning ability in these patients.

Two RCTs in which participants received levodopa for longer periods showed larger positive effects than the short dose studies. In Scheidtmann et al,23 participants received physical therapy (PT) and either levodopa or placebo for 3 weeks, followed by 3 weeks of PT only.23 Researchers found that after the first three weeks, patients receiving levodopa showed significantly better improvements on the Rivermead Motor Assessment (RMA) that were maintained or further increased by the end of the second 3 weeks. In a small singleblind randomized crossover study, Acler et al27 administered levodopa or placebo for 5 weeks to patients with chronic stroke. While RMA scores remained unchanged, the group of patients taking levodopa showed significantly greater improvements in walking speed and manual dexterity and a longer cortical silent period (CSP) with TMS, which was significantly correlated with better manual dexterity. This finding led the authors to conclude that levodopa exerted its positive effects on motor performance by enhancing excitability of the motor cortex.

In a series of individual case reports by Kakuda et al,28 persons with chronic stroke received levodopa daily for 7 weeks, as well as in-patient TMS and occupational therapy (OT) during weeks 2 and 3.28 While no inferential statistics were used, all 5 patients showed improvements on measures of motor functioning after the in-patient portion of the study, which were maintained until the end of the study at week 7. Samuel et al29 piloted the use of levodopa in combination with virtual reality (VR). Participants received levodopa with either conventional therapies or VR for 2 weeks. All showed improvements in motor functioning, but those receiving VR therapy showed higher mean improvement than the levodopa plus conventional therapy group. The authors noted that the amount of change in the VR therapy group was clinically significant based on established values, but no group statistics were done because there were only 2 participants in the levodopa-conventional therapy group.

Two trials studied the effects of levodopa plus a second dopaminergic medication and PT. Sonde and Lökk30 recruited participants 5 to 10 days poststroke and divided them into 4 groups: (1) levodopa only, (2) dextroamphetamine only, (3) levodopa and dextroamphetamine, and (4) placebo. Drugs were administered for 2 weeks and participants were followed for 3 months.30 While all showed significant improvements in motor function over the 3-month period, no group was significantly different from the others. However, only 21 completed the study with each of the groups containing 3 to 7 patients, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. In a second study with the same 4-group design, Lokk et al31 administered levodopa and/or methylphenidate or placebo 15 to 180 days poststroke. All received medication for 3 weeks and were followed for 6 months. Those receiving one or both drugs showed significantly greater improvements in activities of daily living (ADL) as measured by the Barthel Index and in neurological symptoms associated with stroke compared to those receiving placebo; however, there were no significant differences between medication groups. Changes in motor function as measured by the Fugl-Meyer between drug and placebo groups were not statistically different, although the authors noted that the study was underpowered.

Dextroamphetamine and Stroke

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies examined the effects of dextroamphetamine (AMPH) on motor recovery after stroke. Crisostomo et al32 gave a single dose of AMPH 3 to 10 days poststroke, while Walker-Batson et al33 had patients 16 to 30 days poststroke participate in 10 sessions over 40 days. Despite differences in time since injury and intervention length, both studies found significantly greater motor function improvements in the medication groups compared with placebo.

Methylphenidate and Stroke

Treatment with methylphenidate (MP) has also shown some positive outcomes after stroke. After 3 weeks of treatment, Grade et al34 found that the MP group showed significantly greater improvements in motor function than placebo.34 Wang et al35 treated patients who had a stroke with either MP, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), or a combination of the 2 (no placebo group). The authors found no changes in cortical excitability from baseline to posttreatment; however, they found that the combination of MP and tDCS resulted in significantly greater improvement in hand function than either treatment alone. In 8 patients, Tardy et al36 coupled a single dose of MP versus placebo with a 20-minute passive training session of wrist and finger extension, induced by electrical stimulation. Patients on MP showed significant improvement on only 1 of 8 motor outcomes, the finger tapping task (FTT). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was performed, and compared with placebo, MP induced hyperactivation of the ipsilesional primary sensorimotor cortex (S1M1) that was correlated with better performance on the FTT. The authors noted that in another study, increased activation of the S1M1 after stroke was also correlated with improved motor recovery.37

Other Dopaminergic Medications and Stroke

Two studies, with 33 and 16 participants with stroke, respectively, studied the effects of ropinirole and rotigotine, 2 dopamine agonists generally used to treat Parkinson’s disease and restless leg syndrome.38,39 Neither drug produced significant improvements on various tests of motor function compared with placebo.

Levodopa and Traumatic Brain Injury

Two older case reports were found that studied the effects of levodopa on motor outcomes in TBI. In the first, Lal et al40 treated 12 participants with moderate to severe TBI 3 to 52 months postinjury. Treatment length varied between 3 and 24 months, with 2 continuing the medication past the study conclusion. Nine of 11 participants showed improvements in mobility and ADLs, but no statistical analyses were done.

Koeda et al41 reported on a 9-year-old girl with a severe TBI 22 months postinjury who still had severe motor and speech disturbances after prolonged rehabilitation. Before starting levodopa, she had no bed or functional mobility but after 6 weeks of treatment, she was able to roll over by her-self and maintain a seated position for 5 minutes. After 3 months, she could knee walk for 50 meters as well as control hand movement well enough to write.

Amantadine and TBI

In a case report from 1999, Shiller et al42 treated an 18-year-old with amantadine 15 years after a TBI that left him in a coma for 2 months. Amantadine is a dopamine agonist commonly used to treat TBI and disorders of consciousness.43 In the 9-week study period (3 weeks of PT alone, followed by 6 weeks of PT and amantadine), the patient showed significant improvements in bed-to-wheelchair transfers.

Levodopa and Cerebral Palsy

Only 2 studies were found on the use of dopaminergic medication in CP, both case reports. Rosenthal et al44 treated 9 patients with CP. Two dropped out, one for reasons unrelated to the trial and the other due to intolerable side effects. The other 7 participants continued levodopa therapy past the 12-month study end date, and 6 showed improvements in tasks such as handwriting, fine and gross motor control, ADLs, walking, and sitting and standing posture. During the study period, Rosenthal at al44 imbedded a double-blind placebo trial in which 6 participants received a placebo for 2 to 6 weeks. The authors observed that 5 of the 6 had a noticeable decrease in performance. No statistical analyses were done.

Brunstrom et al45 reported on a 16-year-old girl with spastic quadriplegic CP with significant motor impairments and who had never been able to walk. After 2 weeks of levodopa treatment, she showed functional improvements in that she was better able to reach with both arms and pull herself up onto her hands and knees. Additionally, she performed a reach to target task before and after her morning dose of levodopa in which researchers recorded upper limb kinematics and EMG from 6 different muscles. After taking levodopa, she showed significant improvements in her ability to sustain a static arm position during the hold phase of the task, as well as significant decreases in EMG activity during both movement and hold phases.

Levodopa and Spinal Cord Injury

Two studies have examined the effects of levodopa on people with spinal cord injuries (SCI). Maric et al46 treated 12 patients with incomplete SCI, 1 to 4 months postinjury, in a randomized crossover design with 6 weeks of both levodopa and placebo. No significant differences were found between placebo and levodopa conditions on measures of motor recovery, walking function, or ADLs. Radhakrishna et al47 only measured leg movements and EMG activity from 4 muscles bilaterally in 45 patients with complete or motor-complete SCI for at least 3 months. In this dose-escalation study, participants received a single dose of either levodopa or buspirone alone, or both combined. Buspirone is an anxiolytic that is primarily a serotonin agonist but also increases dopamine synthesis and availability.48 No patients receiving levodopa or buspirone separately exhibited significant changes in EMG activity; however, 8 of 25 patients receiving both drugs showed significant increases in EMG activity as well as spontaneous rhythmic leg activity.

Genetic Studies and Motor Recovery

Both Kim et al49 and Liepert et al50 followed patients for 6 months poststroke, assessing their motor recovery several times over the 6-month period. While Kim et al49 found no effect of DRD1–3 alleles, both studies found a significant effect of different COMT polymorphisms. The 3 possible variations are Val/Val, Val/Met, and Met/Met; Liepert et al50 looked at all 3 separately, while Kim et al49 combined these into groups of Met+ (Val/Met and Met/Met) and Met− (Val/ Val). Both found that patients with the Met− polymorphism experienced the best motor recovery. Liepert et al50 observed that the Val/Met polymorphism was associated with a level of recovery in between Val/Val (best) and Met/Met (worst), suggesting a gene-dose relationship.

Diaz-Heijtz et al51 performed a study with children with CP in which they calculated a gene score from 0 to 5 based on polymorphisms of COMT, DRD1–3, and DAT similar to that reported in Pearson-Fuhrhop et al15 and correlated this score with functional gains that had been achieved from previous participation in constraint-induced movement therapy. The authors found that a higher gene score was associated with greater functional gains from treatment. The relationship was strongest when all 5 genes were included in the score, but DAT and DRD1 had the greatest individual associations with outcomes. These 3 studies contribute to the emerging body of evidence that dopamine gene polymorphisms may contribute to motor recovery after neurological injury as well as the response to motor interventions.

Side Effects

None of the studies in this review reported any serious adverse events, although most drugs were associated with some negative side effects. The most common side effects included vertigo, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, vomiting, sleep disturbances, involuntary movements, depression, muscle stiffness, and dry mouth. Only 3 patients reportedly dropped out of studies due to drug side effects: 2 patients in the study by Acler et al27 due to muscle stiffness (levodopa) and 1 patient in the study by Rosenthal et al44 due to excessive nausea and vomiting (levodopa). One patient taking methylphenidate also reported psychostimulation that lasted for 2 weeks.37 Importantly, 12 of the 31 studies did not report on any side effects, which is concerning as the safety of several medications, especially amphetamines, is still unknown.52

Effects of Age, Sex, and Co-interventions

All but one study reported the sex of the participants by group, if indicated, and males were found to be overrepresented with 64% of participants across included studies being male. Seven studies employed a cross-over design, which controls for differences in these factors; only 2 studies34,38 statistically compared sex and age differences across groups at baseline with another comparing age only,35 each of which found no significant differences. None of the RCTs evaluated outcomes based on sex or age. Only one study51 evaluated the association of sex and age with treatment outcomes and found only age to be significantly related.

Co-interventions that could potentially affect motor outcomes are described in Tables 1 and 2 in as much detail on the type or dose of therapy or training as described in each study. Several studies evaluated the effects of the medications during a specific motor training paradigm.24,25,33,38 Nine studies did not state whether therapy was provided during the study period although 2 of those did indicate that the participants were inpatients. Four studies merely mentioned that all had inpatient rehabilitation23,34,49,50 with another stating only that participants received comprehensive rehabilitation.42 One pilot study29 was focused solely on the additive effect of VR versus conventional PT with levodopa but no statistical analyses were done. Four studies provided specific and intensive therapy in the treatment and control arms, and 3 of those that provided activity-based therapies showed no added benefit in the medication group30,38,46; however the one that provided neurodevelopmental therapy did show a positive benefit for medication.31

Discussion

Taken together, the research studies in this systematic review indicate that dopaminergic medication, with the preponderance of evidence on levodopa and its use in stroke, may improve motor recovery and responses to training after a nonprogressive neurological injury. Nineteen of 24 clinical studies across conditions identified at least one positive benefit from a dopaminergic medication. Studies evaluating effects of levodopa on motor recovery after stroke demonstrated some promising results but were still inconclusive. While Restemeyer et al24 did not find an effect from a single dose of levodopa on functional recovery, Floel et al25 and Rosser et al26 provided evidence that 1 to 3 doses could modulate learning and formation of motor memories. Longer administration, often combined with OT or PT, appears to have a more significant impact on motor outcomes, and may do so by modulating motor cortex excitability and ability to learn and encode motor memories. Insufficient details on physical or occupational therapy in many of the included studies limit the conclusions that can be made about the effectiveness or efficacy of the medications; however, the finding of no significant additive effects of dopaminergic medications in the 3 studies incorporating intensive activity-based therapy approaches suggests that therapy may at least partly account for, or obscure the effects of medication on, improved motor outcomes.

It is important to note that not all longer dose studies found beneficial effects. One reason for this discrepancy may have to do with the variable time since injury: 2 of 3 studies with patients within about 1 month of injury found no positive effects of levodopa, one of which was a large randomized trial, while only 1 of 7 studies with participants beyond 1 month found no effects, and notably that trial only gave a single dose of levodopa.24 Therefore, longer administration of levodopa in chronic stroke may have more significant effects on motor recovery than in acute stroke. More data on whether or how a brain or spinal cord injury affects dopamine release and how any potential effects may differ throughout recovery are needed to determine if there is an underlying rationale for these seemingly disparate responses to levodopa during early and late recovery.

Compared with stroke, there is a dearth of human studies on the efficacy of dopaminergic medications in CP, TBI, and SCI and the level of evidence for existing studies is low. Only a handful of case reports were found with small sample sizes and lacking adequate controls. Few presented statistical findings and most failed to report the clinical significance of the observed improvements. However, the promising preliminary results that dopaminergic medications may provide motor benefit and that specific genes related to dopamine transmission in the brain may predict responses from motor training warrant further investigation.

The positive results in the majority of studies here are supported by what is known about the underlying mechanisms by which dopamine affects motor learning and how brain injury affects dopamine systems. Dopaminergic neurotransmission in M1 modulates synaptic plasticity, specifically by increasing long-term potentiation.9 Dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and, to a lesser extent, the substantia nigra (SN) to M1 are necessary for motor learning, supported by evidence from. VTA-lesioned animals who were unable to learn a novel motor task.10,53 TBI frequently results in injuries to the midbrain and brainstem, indicating that dopaminergic projections from the VTA and SN may be particularly susceptible to brain injury.54 Indeed, rats with experimental TBI exhibited declines in dopamine functioning and motor learning, which was ameliorated by the administration of dopamine medications.16–18 Stroke and CP can also affect the midbrain and brainstem, resulting in a loss of dopaminergic neurotransmission.55,56 Therefore, administering dopaminergic medications could mitigate the loss of functioning.

Another important consideration when evaluating inconsistent results across clinical studies is variation in genes related to dopamine neurotransmission shown to be related to individual responses to these medications in healthy adults. The relationship between dopamine and performance has been described as a U-shaped curve whereby too much dopamine could result in a “dopamine overdose.”57,58 Indeed, Qian et al12 found that a strain of rats with overexpression of certain dopamine genes had motor learning deficits compared with a strain with normal expression. Therefore, dopaminergic medications may only be beneficial to people with lower dopaminergic neurotransmission, which alone could help explain some of the inconsistencies in the results across studies. In an RCT not included here because data have only been published as a conference proceedings abstract, no difference in motor outcomes was found in a sample of nearly 600 patients 5 to 42 days poststroke who received PT, OT while randomized to either levodopa or placebo for 6 weeks, and followed for 12 months.59 The therapy was at least 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week for 6 weeks and consisted of active motor, functional skills, and/or speech and language training depending on the needs of the patient. These results differed from the other longer term trials of levodopa poststroke23,27 but are strikingly similar to those of Pearson-Fuhrhop et al15 in which no mean group differences in learning were found in a cohort of healthy adults given either levodopa or placebo during motor training. In that study, responses to either the drug or placebo were associated with individual variations in dopamine transmission genes. Genetic information may therefore be critically important in informing individual treatment prescriptions after neurological injury. More studies are needed to assess the importance of each dopamine gene and address if results are similar or different across pathologies. For example, post-stroke, COMT was the only gene thus far associated with motor outcomes, while in healthy adults and children with CP, DRD1 and DRD2 had stronger associations.15,49,51 Since most genetic studies are examining associations that were largely done retrospectively to interpret outcomes, the findings while compelling should be viewed with caution until results from prospective causal studies are available.

Of note, with one exception, the effects or age and sex on outcomes were not considered here. The presence of age-related declines in the brain dopamine system60,61 may be particularly important to consider when comparing effects of medications across conditions that may vary considerably in the mean age of the participants, such as TBI or SCI, which may occur in many younger adults versus stroke that is far more prevalent in older adults. Considerable evidence on sex differences in the distribution of dopamine neurons throughout the brain as well as other specific differences in dopamine metabolism and transmission18,62,63 provides a strong rationale for separate analyses of outcomes in males and females in future studies so as to further improve individualized prescriptions of dopaminergic medications.

Conclusions

While the use of dopaminergic medications to enhance recovery after a central nervous system injury shows promise, more randomized, adequately powered, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies or rigorous pragmatic trials are needed to better understand the effects of these drugs and the extent to which they can alter prognosis and enhance the quality of life for those with neurological injuries. More studies are also needed on training strategies that affect dopamine release, for example, use of rewards-based training as well as exploration of a broader range of dopaminergic medications. Optimizing treatment timing, dose and duration will be an important goal going forward as well as determining the safety profile and long-term effects of these drugs. Additionally, research should focus on replicating these results in children as there might be different effects and safety profiles. Similarly, age and sex differences must also be taken into consideration when designing, analyzing and interpreting studies. A translation gap between the abundant animal literature and human research and clinical practice is also apparent and needs to be addressed. Yet, still more animal research on different injury mechanisms and severities is needed and will enable us to gain a better understanding of the underlying biochemical mechanisms of how injuries, drugs, and other interventions affect the brain. Finally, it is increasingly apparent that more personalized neurorehabilitation treatment approaches are warranted and individual genetic variations in response to motor training or to medications that could enhance learning need to be considered prospectively before treatment regimens are implemented.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (Protocol #16-CC-0149).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Kwakkel G, Veerbeek JM, van Wegen EE, Wolf SL. Constraint-induced movement therapy after stroke. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:224–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinderholt Myrhaug H, Østensjo S, Larun L, Odgaard-Jensen J, Jahnsen R. Intensive training of motor function and functional skills among young children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan PW, Sullivan KJ, Behrman AL, et al. Body-weight supported treadmill rehabilitation after stroke. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2026–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damiano DL, DeJong SL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of treadmill training and body weight support in pediatric rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther 2009;33:27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomason P, Graham HK. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: the state of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:390–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damiano DL. Meaningfulness of mean group results for determining the optimal motor rehabilitation program for an individual child with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:1141–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Floel A, Breitenstein C, Hummel F, et al. Dopaminergic influences on formation of a motor memory. Ann Neurol 2005;58:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamasy V, Koranyi L, Phelps CP. The role of dopaminergic and serotonergic mechanisms in the development of swimming ability of young rats. Dev Neurosci 1981;4:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina-Luna K, Pekanovic A, Rohrich S, et al. Dopamine in motor cortex is necessary for skill learning and synaptic plasticity. PLoS One 2009;4:e7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosp JA, Pekanovic A, Rioult-Pedotti MS, Luft AR. Dopaminergic projections from midbrain to primary motor cortex mediate motor skill learning. J Neurosci 2011;31:2481–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis EJ, Coyne C, McNeill TH. Intrastriatal dopamine D1 antagonism dampens neural plasticity in response to motor cortex lesion. Neuroscience 2007;146:784–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qian Y, Chen M, Forssberg H, Heijtz RD. Genetic variation in dopamine-related gene expression influences motor skill learning in mice. Genes Brain Behav 2013;12:604–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawaki L, Yaseen Z, Kopylev L, Cohen LG. Age-dependent changes in the ability to encode a novel elementary motor memory. Ann Neurol 2003;53:521–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floel A, Garraux G, Xu B, et al. Levodopa increases memory encoding and dopamine release in the striatum in the elderly. Neurobiol Aging 2008;29:267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson-Fuhrhop KM, Minton B, Acevedo D, Shahbaba B, Cramer SC. Genetic variation in the human brain dopamine system influences motor learning and its modulation by L-Dopa. PLoS One 2013;8:e61197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YH, Huang EY, Kuo TT, et al. Dopamine release impairment in striatum after different levels of cerebral cortical fluid percussion injury. Cell Transplant 2015;24:2113–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phelps TI, Bondi CO, Mattiola VV, Kline AE. Relative to typical antipsychotic drugs, aripiprazole is a safer alternative for alleviating behavioral disturbances after experimental brain trauma. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2017;31:25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner AK, Kline AE, Ren D, et al. Gender associations with chronic methylphenidate treatment and behavioral performance following experimental traumatic brain injury. Behav Brain Res 2007;181:200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, et al. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence (Introductory Document). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Accessed February 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhakta BB, Hartley S, Holloway I, et al. The DARS (Dopamine Augmented Rehabilitation in Stroke) trial: protocol for a randomised controlled trial of Co-careldopa treatment in addition to routine NHS occupational and physical therapy after stroke. Trials 2014;15:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheidtmann K, Fries W, Müller F, Koenig E. Effect of levodopa in combination with physiotherapy on functional motor recovery after stroke: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 2001;358:787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Restemeyer C, Weiller C, Liepert J. No effect of a levodopa single dose on motor performance and motor excitability in chronic stroke. A double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2007;25:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Floel A, Hummel F, Breitenstein C, Knecht S, Cohen LG. Dopaminergic effects on encoding of a motor memory in chronic stroke. Neurology 2005;65:472–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosser N, Heuschmann P, Wersching H, Breitenstein C, Knecht S, Flöel A. Levodopa improves procedural motor learning in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1633–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acler M, Fiaschi A, Manganotti P. Long-term levodopa administration in chronic stroke patients. A clinical and neurophysiologic single-blind placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2009;27:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakuda W, Abo M, Kobayashi K, et al. Combination treatment of low-frequency rTMS and occupational therapy with levodopa administration: an intensive neurorehabilitative approach for upper limb hemiparesis after stroke. Int J Neurosci 2011;121:373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuel GS, Oey NE, Choo M, et al. Combining levodopa and virtual reality-based therapy for rehabilitation of the upper limb after acute stroke: pilot study Part II. Singapore Med J 2017;58:610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonde L, Lökk J. Effects of amphetamine and/or L-dopa and physiotherapy after stroke—a blinded randomized study. Acta Neurol Scand 2007;115:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lokk J, Salman Roghani R, Delbari A. Effect of methylphenidate and/or levodopa coupled with physiotherapy on functional and motor recovery after stroke—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Neurol Scand 2011;123:266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crisostomo EA, Duncan PW, Propst M, Dawson DV, Davis JN. Evidence that amphetamine with physical therapy promotes recovery of motor function in stroke patients. Ann Neurol 1988;23:94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker-Batson D, Smith P, Curtis S, Unwin H, Greenlee R. Amphetamine paired with physical therapy accelerates motor recovery after stroke. Further evidence. Stroke 1995;26:2254–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grade C, Redford B, Chrostowski J, Toussaint L, Blackwell B. Methylphenidate in early poststroke recovery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1047–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang QM, Cui H, Han SJ, et al. Combination of transcranial direct current stimulation and methylphenidate in subacute stroke. Neurosci Lett 2014;569:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tardy J, Pariente J, Leger A, et al. Methylphenidate modulates cerebral post-stroke reorganization. Neuroimage 2006;33:913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loubinoux I, Carel C, Pariente J, et al. Correlation between cerebral reorganization and motor recovery after subcortical infarcts. Neuroimage 2003;20:2166–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cramer SC, Dobkin BH, Noser EA, Rodriguez RW, Enney LA. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of ropinirole in chronic stroke. Stroke 2009;40:3034–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorgoraptis N, Mah YH, Machner B, et al. The effects of the dopamine agonist rotigotine on hemispatial neglect following stroke. Brain 2012;135(pt 8):2478–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lal S, Merbtiz CP, Grip JC. Modification of function in head-injured patients with Sinemet. Brain Inj 1988;2:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koeda T, Takeshita K. A case report of remarkable improvement of motor disturbances with L-dopa in a patient with post-diffuse axonal injury. Brain Dev 1998;20:124–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiller AD, Burke DT, Kim HJ, Calvanio R, Dechman KG, Santini C. Treatment with amantadine potentiated motor learning in a patient with traumatic brain injury of 15 years’ duration. Brain Inj 1999;13:715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giacino JT, Whyte J, Bagiella E, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2012;366:819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenthal RK, McDowell FH, Cooper W. Levodopa therapy in athetoid cerebral palsy. A preliminary report. Neurology 1972;22:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brunstrom JE, Bastian AJ, Wong M, Mink JW. Motor benefit from levodopa in spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol 2000;47:662–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maric O, Zörner B, Dietz V. Levodopa therapy in incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2008;25:1303–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radhakrishna M, Steuer I, Prince F, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase I/IIa sStudy (safety and efficacy) with buspirone/levodopa/carbidopa (Spinalon™) in subjects with complete AIS A or motor-complete AIS B spinal cord injury. Curr Pharm Des 2017;23:1789–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loane C, Politis M. Buspirone: what is it all about? Brain Res 2012;1461:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim BR, Kim HY, Chun YI, et al. Association between genetic variation in the dopamine system and motor recovery after stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2016;34:925–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liepert J, Heller A, Behnisch G, Schoenfeld A. Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism influences outcome after ischemic stroke: a prospective double-blind study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2013;27:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diaz-Heijtz R, Almeida R, Eliasson AC, Forssberg H. Genetic variation in the dopamine system influences intervention outcome in children with cerebral palsy. EBioMedicine 2018;28:162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sprigg N, Bath PM. Speeding stroke recovery? A systematic review of amphetamine after stroke. J Neurol Sci 2009;285: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hosp JA, Luft AR. Dopaminergic meso-cortical projections to m1: role in motor learning and motor cortex plasticity. Front Neurol 2013;4:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams JH, Doyle D, Ford I, Gennarelli TA, Graham DI, McLellan DR. Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology 1989;15:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moncayo J Midbrain infarcts and hemorrhages. Front Neurol Neurosci 2012;30:158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolawole TM, Patel PJ, Mahdi AH. Computed tomographic (CT) scans in cerebral palsy (CP). Pediatr Radiol 1989;20: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaillancourt DE, Schonfeld D, Kwak Y, Bohnen NI, Seidler R. Dopamine overdose hypothesis: Evidence and clinical implications. Mov Disord 2013;28:1920–1929. doi: 10.1002/mds.25687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cools R, D’Esposito M. Inverted-U shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry 2011;69:e113–e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ford G, Bhakta B, Cozens A, et al. DARS (Dopamine Augmented Rehabilitation in Stroke): Longer-term results for a randomised controlled trial of Co-careldopa in addition to routine occupational and physical therapy after stroke. Int J Stroke 2015;10:5–13.26496664 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mozley PD, Acton PD, Barraclough ED, et al. Effects of age on dopamine transporters in healthy humans. J Nucl Med 1999;40:1812–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Volkow ND, Gur RC, Wang GJ, et al. Association between decline in brain dopamine activity with age and cognitive and motor impairment in healthy individuals. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Panzica G, Melcangi RC. Structural and molecular brain sexual differences: a tool to understand sex differences in health and disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;67:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Myrga JM, Failla MD, Ricker JH, et al. A dopamine pathway gene risk score for cognitive recovery following traumatic brain injury: methodological considerations, preliminary findings, and interactions with sex. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2016;31:E15–E29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]