Abstract

Pistacia weinmannifolia (PW) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat headaches, dysentery, enteritis and influenza. However, PW has not been known for treating respiratory inflammatory diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The present in vitro analysis confirmed that PW root extract (PWRE) exerts anti-inflammatory effects in phorbol myristate acetate- or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α)-stimulated human lung epithelial NCI-H292 cells by attenuating the expression of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6 and Mucin A5 (MUC5AC), which are closely associated with the pulmonary inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of COPD. Thus, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the protective effect of PWRE on pulmonary inflammation induced by cigarette smoke (CS) and lipopoly-saccharide (LPS). Treatment with PWRE significantly reduced the quantity of neutrophils and the levels of inflammatory molecules and toxic molecules, including tumor TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, neutrophil elastase and reactive oxygen species, in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. PWRE also attenuated the influx of inflammatory cells in the lung tissues. Furthermore, PWRE downregulated the activation of nuclear factor-κB and the expression of phosphodiesterase 4 in the lung tissues. Therefore, these findings suggest that PWRE may be a valuable adjuvant treatment for COPD.

Keywords: Pistacia weinmannifolia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, airway inflammation, neutrophils, NF-κB, interleukin-8

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major health problem, and its incidence has continued to increase globally in the past decade (1,2). Airway inflammation, one of the main forms of COPD, is caused by cigarette smoking and its pathogenesis is closely associated with increased levels of inflammatory molecules (3). Bacterial respiratory tract infections are associated with the initial occurrence and exacerbation of the airway inflammatory response in COPD (4). The increased concentration of neutrophils is a unique characteristic and clinical indicator of COPD, and cell-derived toxic molecules, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neutrophil elastase (NE), cause oxidative stress and emphysema (5,6). The release of interleukin (IL)-8 by bronchial epithelial cells leads to an increase in neutrophil and macrophage chemotaxis (7). Macrophage activation has been reported to cause the airway inflammatory response via the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (8,9). It is well understood that the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) leads to the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and MCP-1 (10-12).

Natural products and their derivatives have been used for the treatment of various diseases, including infectious diseases, and have been reported to serve an important role in the prevention of inflammatory diseases (13-15). It is well known that Traditional Chinese Medicine exerts valuable therapeutic effects on pulmonary diseases (16). Pistacia weinmannifolia (PW) is a plant predominantly distributed in the Yunnan province of China and is used as a herbal remedy for treating dysentery, enteritis, influenza and lung cancer (17,18). The major metabolites of PW have been reported to possess a wide variety of biological activities, including antioxidant effects and histamine-release inhibition (19). However, to the best of our knowledge, its protective effect against cigarette smoke (CS)- and lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced pulmonary inflammation remains to be elucidated in a mouse model. Based on results of previous studies (17-19) and an observation from the present in vitro study, which demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of PW root extract (PWRE), the protective effect of PWRE against CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation was examined.

Materials and methods

Preparation of PWRE

PW roots were collected in the Yunnan province of China in August 2017 and identified by Dr Sangwoo Lee (International Biological Material Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, South Korea). A voucher specimen (D180305001) of this raw material was deposited at the International Biological Material Research Center (http://www.ibmrc.re.kr/) of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (Chungbuk, Korea). The drug substance from the PW roots was produced by a processing method described in the International Conference on Harmonisation and Ministry of Food and Drug Safety guidelines (http://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/wpge/m_17/de011008l001.do). The collected roots were dried immediately after sampling and then ground to a powder and stored at a temperature lower than −20°C prior to extraction. The raw materials were then packed in laminated bags, delivered to Korea and stored at -25°C for 3 months until further analysis and biological testing. The extracts of PW roots were provided by the BTC Corporation (Korea Good Manufacturing Practice; cat. no. BTC-PWE-180118). The powdered samples were extracted twice with 50% ethanol at 80°C and concentrated in vacuo at 60°C. The product was dried in a freeze dryer to produce dried extracts (~19% yield).

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTof-MS)

UPLC-QTof-MS (Micromass Q-Tof Premier™, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) analyses were performed with an ACQUITy BEH C18 chromatography column (2.1×100 mm; 1.7 µm; Waters Corporation) with a linear gradient (0 min, 1% B; 0-1.0 min, 1-5% B; 1.0-10.0 min, 5-30% B; 10.0-17.0 min, 30-60% B; 17.0-17.1 min, 60-100% B; 17.1-19.0 min, 100% B; 19.0-20.0 min, back to 1% B) of acetonitrile/water (HPLC-grade; Merck KGaA). The injection volume was 2 µl. The QTof-MS was operated in negative ion mode with the following conditions: Source temperature, 110°C; desolvation temperature, 350°C; capillary voltage, 2,300 V; and cone voltage, 50 V. Leucine-enkephalin (400 pg/ml) was used as the reference compound (m/z 554.2615 in the negative mode) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Accurate mass, MS/MS and elemental composition were calculated using the MassLynx software (Waters Corporation) incorporated into the instrument.

Cell preparation and culture

Human lung epithelial NCI-H292 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (catalog no. CRL-1848; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (HyClone; GE Healthcare) at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

For the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to assess IL-8, IL-6 and MUC5AC production, NCI-H292 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells for 16 h. The cells were then transferred to reduced-serum medium (0.1% FBS). After a 16-h incubation period, the cells were treated with PWRE for 2 h prior to adding inflammatory stimuli, including 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) or 20 ng/ml TNF-α (PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) based on the previous reports (20-23). After the addition of the stimuli, the cells were further incubated for 12 h at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cell viability assay

NCI-H292 cells were seeded and cultured in 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 medium at a density of 5×103 cells/well for 16 h. The medium was subsequently replaced with a reduced-serum medium (0.1% FBS). After a 16-h incubation, the cells were cultured with the corresponding concentrations (1, 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/ml) of PWRE in the presence or absence of inflammatory stimuli, including PMA (100 nM) or TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 24 h at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell growth was measured in triplicate using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a BioTek microplate reader and calculated as a percentage of the control value for each condition.

Mouse model of pulmonary inflammation induced by CS and LPS

In mice, the inhalation of CS and the administration of LPS accelerates the airway inflammatory response similar to what is seen in patients with COPD (2,3,24). Therefore, CS exposure and LPS administration were achieved using a modification of the methods described by Lee et al (25). Briefly, six-week-old C57BL/6N male mice (n=24; body weight, 18-20 g) were obtained from Koatech Co. Ltd. (Pyeongtaek-si, Korea), quarantined and acclimated to a specific pathogen-free system for ≥1 week prior to the experiments (22-23°C; 55-60% humidity; 12 h light/dark; free access to food and water). The mice were randomly divided into five subgroups (n=6 per subgroup) as follows: i) normal control (NC) group; ii) CS exposure/LPS intranasal administration (CS + LPS) group; iii) CS exposure/LPS administration + 5 mg/kg roflumilast oral gavage (ROF) group (used as a positive control group); and iv) CS exposure/LPS administration + 15 mg/kg PWRE oral gavage (PW) group. 3R4F research cigarettes were purchased from the Tobacco and Health Research Institute at the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY, USA), and the mice were exposed to fresh room air or CS from eight cigarettes for 60 min/day for 6 days using a smoking machine (SciTech Korea, Inc., Seoul, Korea). PWRE and roflumilast (ROF) were orally administered for six consecutive days prior to CS exposure. LPS (5 µg dissolved in 30 µl distilled water) was intranasally instilled on day 5. The experimental procedures of this study were performed in accordance with the procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (Chungbuk, Korea; KRIBB-AEC-18054) and in compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Korean national laws for animal welfare.

Measurement of inflammatory cell count

To distinguish the different cells, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected as described previously (26). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with Zoletil 50® (30-50 mg/kg IP; Virbac, Co., Seoul, Korea) and Xylazine (5-10 mg/kg IP; Bayer Korea, Seoul, Korea) 24 h after the intranasal administration of LPS. The anesthetic conditions were based on previous studies (27,28), which provide information on the usefulness of the combined use of Zoletyl with Xylazine. This combined administration adequately maintained sedation and analgesia. Toxic signs, including dyspnea and vomiting, were not observed in this condition. BALF was collected by tracheal cannulation and infusion with 0.7 ml ice-cold PBS twice (total volume, 1.4 ml). To count the inflammatory cells, 0.1 ml BALF was centrifuged onto a slide using a Cytospin (Hanil Science Industrial, Seoul, Korea) at 246 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and the slides were dried and stained using the Diff-Quik® staining reagent (cat. no. 38721; Sysmex Corporation, Ltd., Japan), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Finally, inflammatory cells were counted under a light microscope (magnification, ×400), with ≥4 fields counter per BALF sample.

Determination of inflammatory cytokines and toxic molecules

The levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and MCP-1 in the BALF were measured using ELISA kits, according to the manufacturers' protocols. The IL-6 (cat. no. 555240) and TNF-α (cat. no. 558534) ELISA kits were purchased from BD Biosciences, the IL-8 kit (cat. no. MBS261967) was from MyBioSource, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), and the MCP-1 kit (cat. no. DY479) was obtained from (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). To evaluate the levels of IL-6, IL-8 and MUC5AC in the human NCI-H292 cells, the presence of cytokines in the supernatant was analyzed using human IL-6 and IL-8 ELISA kits (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Human MUC5AC protein levels were measured by modified ELISA assay using anti-MUC5AC (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), as previously described (29). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Spark™ 10 M multimode microplate reader (Tecan Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). To measure the intracellular ROS activity, the BALF cells were incubated with 20 µM 2′,7′-dichloroflurorescein diacetate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 10 min. at 37°C. The results were observed using a fluorescence plate reader (488 nm excitation and 525 nm emission). The level of NE activity was monitored using N-succinyl-(Ala)3-p-nitroanilide (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KgaA) at 37°C for 90 min. The absorbance was read at 405 nm using an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) and used to calculate the percentage of the control for each condition.

Western blot analysis

The lung tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer (cat. no. c3228; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors (cat. nos. 04906837001 and 11836153001, respectively; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The Pierce BCA Protein assay kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to determine the protein concentration. Equal quantities of proteins (50 µg/lane) were separated by 10-15% SDS-PAGE and the proteins were then transferred onto PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk for 1 h and probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. The primary antibodies and dilutions were as follows: Anti-phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB p65 (cat. no. 3033; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), anti-IκB-α (cat. no. 2859; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-β-actin (cat. no. 4967; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-NF-κB p65 (cat. no. sc-372; 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), anti-p-IκB-α (cat. no. MA5-15087; 1:1,000; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and anti-PDE4B (cat. no. ab170939; 1:1,000; Abcam). The membranes were washed with TBS and 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. no. 111-035-003; 1:2,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) at room temperature for 2 h. Finally, the membranes were washed with TBST and developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All bands were visualized by the LAS-4000 luminescent image analyzer (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified by densitometry using Fuji Multi Gauge software version 3.0 (Fuji photo film Co, Ltd. Japan).

Histological analysis

The lung tissues were removed from the mice 24 h after the last oral administration of PWRE and fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin solution (BBC Biochemical, Mount Vernon, WA, USA) at room temperature for 48 h. For histological evaluation, the lung tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm using a rotary microtome. Subsequently, the lung sections were stained with a hematoxylin (cat. no. 3580; BBC Biochemical Inc.) and eosin (cat. no. 6766007; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) solutions at room temperature for 30 sec each. The sections were visualized using a light microscope (magnification, ×100) to estimate the influx of inflammatory cells. The degree of inflammatory cell influx in each group was examined by three independent observers using the following semi-quantitative scope: 0, no influx; 1, low influx; 2, moderate influx; 3, large influx; and 4, severe influx.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t-test for comparisons between two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test was used to analyze differences between multiple groups. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Extract of PWRE

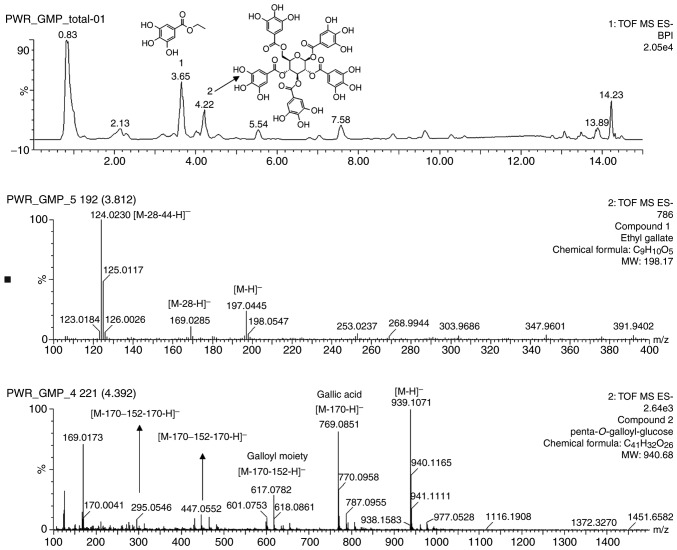

The high potency of the P. weinmannifolia roots indicated the presence of compounds that may be therapeutic against COPD. Therefore, the major compounds of the extracts were expected to exhibit inhibitory activities. Following the analysis, the major compounds were characterized using mass data. As presented in Fig. 1, it was revealed that the deprotonated molecule [M-H]− was the most abundant for two compounds: m/z 197 for ethyl gallate (C9H10O5) and m/z 939 for penta-O-galloyl-glucose (C41H32O26).

Figure 1.

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry chromatogram of the identified marker substances from extracts of the Pistacia weinmannifolia roots.

Effects of PWRE on PMA- or TNF-α-stimulated NCI-H292 cells

PMA and TNF-α are potent pro-inflammatory stimuli that are used extensively to induce secretagogue effects on the human respiratory epithelium, and they are a good in vitro model for evaluating the inflammatory response (30). NCI-H292 cells, a human pulmonary mucoepidermoid carcinoma cell line, are often used for the purpose of elucidating the inflammatory response involved in airway inflammatory gene expression and mucin secretion (31). Thus, the present study investigated whether PWRE suppresses the inflammatory response in PMA- or TNF-α-stimulated human lung epithelial NCI-H292 cells. Prior to this investigation, the current study evaluated the cytotoxicity of PWRE in the presence or absence of PMA or TNF-α in NCI-H292 cells and identified that PWRE demonstrates no cytotoxicity at any of the concentrations used (Fig. 2A and E). A concentration <10 µg/ml was used in the subsequent experiments. As presented in Fig. 2B-D, PMA significantly enhanced IL-8, IL-6 and MUC5AC secretion in NCI-H292 cells. This increase in IL-8, IL-6 and MUC5AC secretion was significantly suppressed by treatment with PWRE. Furthermore, PWRE suppressed the expression of TNF-α-induced IL-8 and IL-6 in NCI-H292 cells (Fig. 2F and G). These results indicate that PWRE effectively inhibited the PMA- or TNF-α-induced inflammatory response in NCI-H292 cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of PW on the PMA- or TNF-α-induced inflammatory response in human lung epithelial NCI-H292 cells. (A) No adverse effects were caused by the corresponding concentrations of PW in the presence or absence of inflammatory stimuli, PMA on the NCI-H292 cell viability. Effects of PW on IL-8 (B), IL-6 (C) and MUC5AC (D) production in PMA-stimulated NCI-H292 cells. (E) No adverse effects were caused by the corresponding concentrations of PW in the presence or absence of inflammatory stimuli, TNF-α on the NCI-H292 cell viability. Effects of PW on IL-8 (F) and IL-6 (G) production in TNF-α-stimulated NCI-H292 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #P<0.05 vs. negative control group (0 µg/ml TNF-α). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. 0 µg/ml PW. PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-8, interleukin-8; IL-6, interleukin-6.

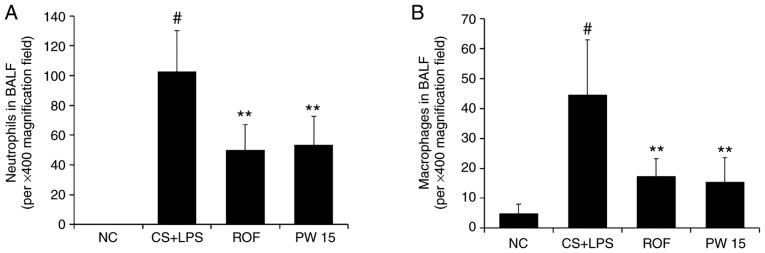

Effects of PWRE on the quantity of inflammatory cells in the BALF of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation animal model

Pulmonary inflammation was achieved by CS exposure and LPS administration (Fig. 3). A significant increase in inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages, was detected in the BALF of the CS+LPS group compared with the NC group (Fig. 4A and B). However, the level of neutrophils was significantly reduced in the PWRE-treated mice compared with the CS+LPS group (P<0.01). The level of macrophages was also decreased to the level of the ROF in the PWRE-treated mice (P<0.01). In total, the inhibitory effects of 15 mg/kg PWRE were similar to those of 5 mg/kg ROF, which was used as a positive control.

Figure 3.

Experimental procedure for the pulmonary inflammation and administration of PW or ROF. C57BL/6N mice were divided into four groups (n=6 in each group). The mice were orally administered PW (15 mg/kg) or ROF (5 mg/kg) from days 1 to 6. On day 5, the mice were given an intranasal administration of 5 µg LPS in 30 µl PBS 1 h after each corresponding PW or ROF administration. On day 7, the mice were sacrificed, and the BALF and lung tissues were harvested. ROF, roflumilast; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; IL, interleukin; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NE, neutrophil elastase; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

Figure 4.

Effect of PW on the quantity of inflammatory cells in the BALF of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. The count of (A) neutrophils and (B) macrophages. Diff-Quik® staining was used to determine the different cells in the BALF. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. **P<0.01 vs. CS+LPS group. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

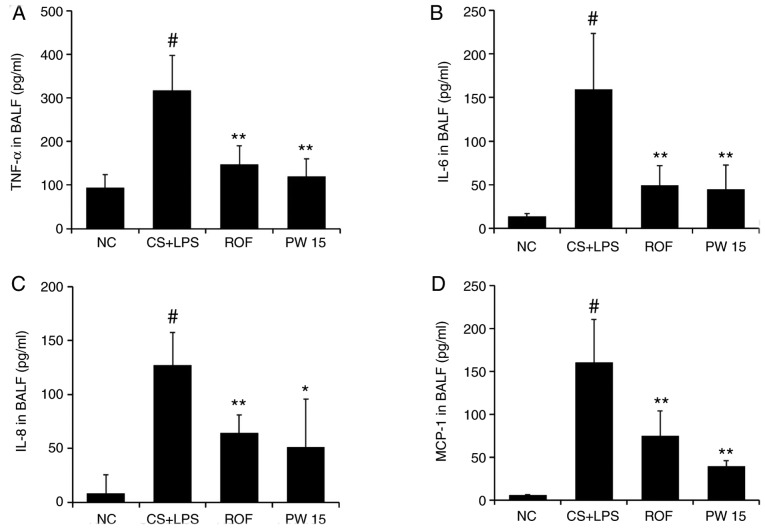

Effects of PWRE on inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BALF of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation animal model

The concentration of inflammatory molecules in the BALF was measured by ELISA. As presented in Fig. 5, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 were significantly higher in the CS+LPS group compared with the NC group, whereas a significant reduction of these molecules was detected in the PWRE-treated group (Fig. 5A-D). Compared with the CS+LPS group, the inhibition levels of ROF against the inflammatory molecules were 53.50 (TNF-α), 68.98 (IL-6), 49.46 (IL-8) and 53.61% (MCP-1; P<0.01), while for PWRE, they were 62.21 (TNF-α), 72.09 (IL-6), 49.46 (IL-8) and 75.53% (MCP-1; P<0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of PW on the levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lungs of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. BALF inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6, (C) IL-8, and (D) MCP-1, were determined by ELISA. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. CS+LPS group. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-8, interleukin-8; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

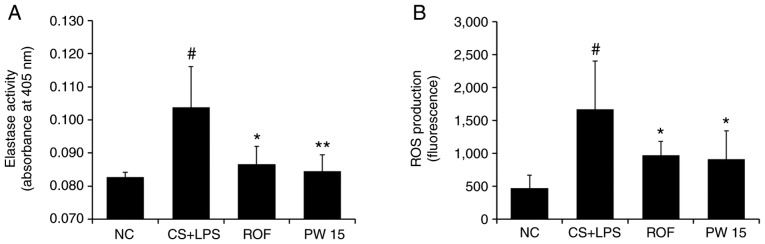

Effects of PWRE on the levels of toxic molecules in the BALF of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation animal model

The present results demonstrated the inhibitory effect of PWRE on neutrophil influx (Fig. 4A). Based on this result, the inhibitory activity of PWRE on the neutrophil-derived toxic molecules NE and ROS was evaluated. As presented in Fig. 6A, a significant increase in NE activity was observed in the CS+LPS group compared with the NC group. However, PWRE-treatment led to a significant reduction in this activity down to the same level as that observed following ROF-treatment. Similarly, the increased production of ROS was also significantly reversed by PWRE-treatment (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of PW on the levels of toxic molecules in the lungs of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. The levels of (A) elastase activity and (B) ROS production were investigated according to each experimental procedure. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. CS+LPS group. ROS, reactive oxygen species; CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

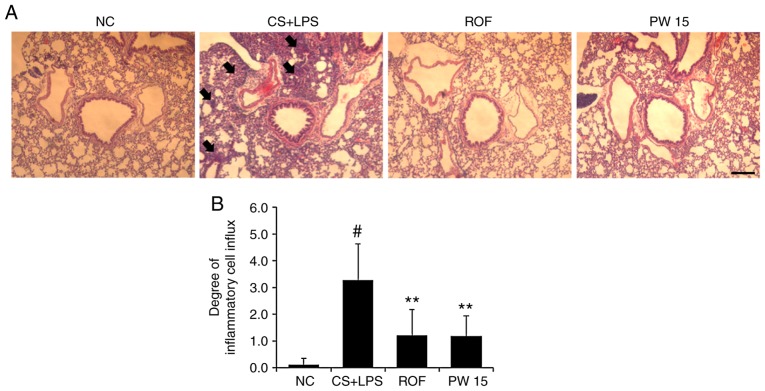

Effects of PWRE on inflammatory cell influx in the lungs of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary animal model

As the present study confirmed the regulatory effects of PWRE on neutrophil recruitment and MCP-1 production (Figs. 4A and 5D), it was next examined whether the inflammatory cell recruitment into the lungs by exposure to CS and LPS is attenuated by PWRE. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to examine histological changes in the lungs. As presented in Fig. 7, in the lungs of the CS+LPS group, the degree of inflammatory cell influx was significantly higher compared with that of the NC group. Notably, the degree of influx was significantly reduced in the lungs of the PWRE group.

Figure 7.

Effect of PW on the influx of inflammatory cells in the lungs of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. (A) Histological change analysis was performed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (peribronchial lesion; magnification, ×100; scale bar, 50 µm). The arrows indicate the influx of inflammatory cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of airway inflammation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. **P<0.01 vs. CS+LPS group. CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

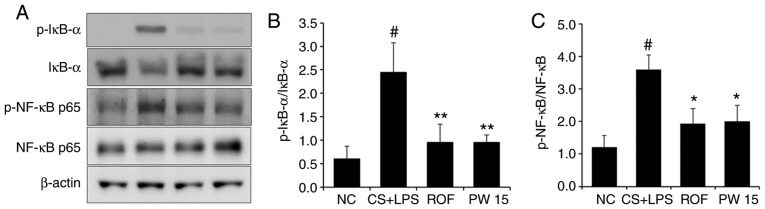

Effects of PWRE on the activation of NF-κB in the lungs of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation animal model

Under inflammatory conditions, the activation of NF-κB leads to the release of inflammatory molecules, including IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 (32-34). The present study confirmed the effect of PWRE on the production of these molecules (Fig. 5). Therefore, it was next evaluated whether PWRE regulates the activation of NF-κB using western blot analysis. As presented in Fig. 8, the level of NF-κB p65 phosphorylation was significantly upregulated in the lung tissues of the CS+LPS group compared with the NC group. However, PWRE-treatment significantly reduced this level in the PWRE group compared with the CS+LPS group. To further clarify the relevance of the NF-κB signaling pathway, the current study next focused on the molecular aspects, including IκB-α, which is a key signaling molecule in the NF-κB pathway (3,26). It is well established that IκB activation and degradation lead to NF-κB activation (35,36). As presented in Fig. 8, the level of IκB-α phosphorylation was significantly upregulated in the lung tissues of the CS+LPS group compared with the NC group, whereas this level was effectively inhibited in the lungs of the PWRE group.

Figure 8.

Effect of PW on NF-κB activation in the lungs of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. (A) Western blot analysis was used to determine the levels of IκB activation and degradation, and NF-κB activation in the lung tissue sample. Quantitative analysis of (B) p-IκB and (C) p-NF-κB levels was performed by densitometric analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. CS+LPS group. NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; p, phosphorylated; CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

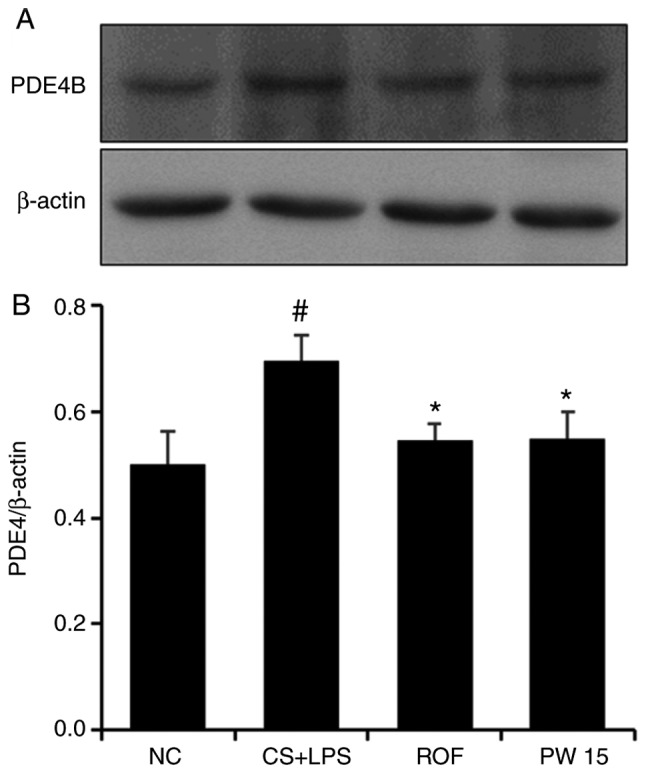

Effects of PWRE on PDE4 expression in the lungs of the CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation animal model

It is well known that PDE4 serves an important role in inflammation (37) and that the PDE4 inhibitor ROF ameliorates airway inflammation induced by CS and LPS (2,3). The appropriated concentration of ROF was determined with reference to the previous studies (38-42). The present study confirmed that PWRE exerts an anti-inflammatory effect by suppressing the influx of inflammatory cells and the production of inflammatory molecules (Figs. 4-7). These effects of PWRE were similar to those of ROF. Based on these results, the current study further investigated the regulatory effect of PWRE on CS- and LPS-induced PDE4 expression. As presented in Fig. 9, the expression of PDE4B was significantly increased in the lung tissues of the CS+LPS group compared with those of the NC group. However, this increase was significantly reduced in the PWRE group compared to the CS+LPS group. Notably, the inhibitory effect of PWRE on PDE4 expression was similar to those in the ROF group. This result was similar to those of a previous study (37).

Figure 9.

Effect of PW on PDE4 expression in the lungs of mice with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. (A) Western blot analysis was used to determine the levels of PDE4 in the lung tissue sample. (B) Quantitative analysis of PDE4 expression was performed by densitometric analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=6). #P<0.05 vs. NC group. *P<0.05 vs. CS+LPS group. PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; CS, cigarette smoke; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PW, Pistacia weinmannifolia root extract; NC, normal control mice; CS+LPS, mice exposed to cigarette smoke and LPS; ROF, mice administered ROF (5 mg/kg) + CS+LPS; PW 15, mice administered PW (15 mg/kg) + CS+LPS.

Discussion

The results of the present in vitro study demonstrated that PWRE inhibits the release of IL-6, IL-8 and MUC5AC, which are important parameters in COPD pathology. In the in vivo study, PWRE inhibited not only inflammatory cell recruitment but also inflammatory molecules. In addition, the levels of toxic molecules were downregulated with PWRE-treatment. These inhibitory activities were accompanied by NF-κB inactivation.

Airway epithelial cell-derived inflammatory molecules, including IL-6, IL-8 and MUC5AC, have been associated with the pathogenesis of COPD (43). IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine that is produced by airway epithelial cells and macrophages, and its increased level is closely associated with infection and the inflammatory response (10,44,45). IL-8 is recognized as an important neutrophil chemoattractant and MUC5AC inducer, and its level is notably upregulated in bronchial epithelial cells from patients with COPD (46). The increased levels of MUC5AC in respiratory epithelial cells lead to lung function decline (10,47). This suggests that controlling IL-6, IL-8 and MUC5AC levels may be an important element in the prevention and treatment of COPD. Therefore, the present study evaluated the inhibitory effect of PWRE on these molecules in activated H292 airway epithelial cells. It was confirmed that PWRE could control the levels of IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and MUC5AC in PMA- or TNF-α-stimulated airway epithelial cells (Fig. 2). Therefore, the protective effect of PWRE on CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation was subsequently investigated.

The persistent pulmonary inflammatory response is a prominent feature of COPD (3). Macrophages and neutrophils have a central role in lung inflammation and destruction (48,49). Macrophages are the initiators of the inflammatory response, and these cell-derived inflammatory cytokines and chemokines promote a hyper-inflammatory immune response (2,50). A previous study reported that the levels of TNF-α were higher in macrophages in patients with COPD compared with nonsmokers without COPD (4). It is understood that COPD is associated with high levels of IL-6 (51), and the influx of macrophages and the levels of IL-6 are upregulated in the lungs of COPD animal models (52,53). In response to CS exposure, macrophage-derived IL-8 and MCP-1 cause neutrophil recruitment (34,54,55). The high level of neutrophil influx is understood to be a typical characteristic of COPD (56). Neutrophils release a protease that causes damage to the endothelial cells of the airway and accelerates lung destruction (57). Neutrophil-derived ROS lead to oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of lung inflammation and are consistently observed in patients with COPD and COPD animal models (58). Therefore, the regulation of macrophage/neutrophil influx and these cell-derived molecules could be a valuable therapeutic approach in COPD. In the present study, it was identified that PWRE reduces not only the number of macrophages but also their cell-derived inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Figs. 4B and 5). The current results also demonstrated that PWRE inhibits neutrophil recruitment and neutrophil-derived toxic molecules (Figs. 4A and 6). In the histological analysis, PWRE regulated the influx of inflammatory cells into the lungs (Fig. 7). Based on the presents results, it can be suggested that the inhibition of inflammatory cell recruitment and inflammatory molecules, including IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1, by PWRE could eventually lead to the amelioration of the pulmonary inflammatory response. These effects of PWRE were similar to those of ROF and therefore are valuable.

NF-κB activation is closely associated with pulmonary inflammation, and this association has been demonstrated in the lung tissues of COPD animal models (59). In recent studies, approaches to reduce the activation of NF-κB have been attempted in in vivo studies, and improvement of pulmonary inflammation was confirmed with NF-κB inactivation (60,61). Therefore, the current study evaluated the regulatory effect of PWRE on NF-κB activation in mouse models with CS- and LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. As presented in Fig. 8, PWRE regulated the levels of IκB phosphorylation, IκB degradation and NF-κB phosphorylation. Therefore, it is expected that PWRE exerts protective effects against the inflammatory response in pulmonary inflammatory disease, including COPD.

PDE4 is also closely associated with the inflammatory response (37). In the present study, PWRE ameliorated pulmonary inflammation, and notably, the inhibitory effects of PDE4 expression by PWRE were similar to those of ROF, the positive control. This result is valuable, and therefore, PWRE is expected to exhibit a protective effect against the inflammatory response in pulmonary inflammatory diseases, including COPD.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time, the present study confirmed that PWRE effectively inhibits inflammatory cell recruitment, toxic molecules and inflammatory mediators. These effects were in accordance with the inhibition of NF-κB. Overall, the current results demonstrated that PWRE exerts a protective role in pulmonary inflammatory response. These findings suggest that PWRE is a potential anti-inflammatory adjuvant treatment in inflammatory diseases, including COPD.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and the Korea Institute for the Advancement of Technology (KIAT) (grant no. N0002410, 2017).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JWL performed the in vivo experiments and wrote the manuscript. HWR contributed to the extraction of P. weinmannifolia roots and contributed to the interpretation of the results. SUL performed the in vitro experiments and contributed to the interpretation of the results. TKO, JKL and TYK contributed to the acquisition of data. MGK, OKK, MOK, SWL, SC, WYL and KSA made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and the analysis and interpretation of data. SRO designed the study and was involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (Cheongju-si, Korea).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Fei X, Bao W, Zhang P, Zhang X, Zhang G, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Zhang M. Inhalation of progesterone inhibits chronic airway inflammation of mice exposed to ozone. Mol Immunol. 2017;85:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SU, Ryu HW, Lee S, Shin IS, Choi JH, Lee JW, Lee J, Kim MO, Lee HJ, Ahn KS, et al. Lignans isolated from flower buds of Magnolia fargesii attenuate airway inflammation induced by cigarette smoke in vitro and in vivo. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:970. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JW, Ryu HW, Lee SU, Son TH, Park HA, Kim MO, Yuk HJ, Ahn KS, Oh SR. Protective effect of polyacetylene from Dendropanax morbifera Leveille leaves on pulmonary inflammation induced by cigarette smoke and lipopolysaccharide. J Funct Foods. 2017;32:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethi S. Infection as a comorbidity of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1209–1215. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JW, Shin NR, Park JW, Park SY, Kwon OK, Lee HS, Hee Kim J, Lee HJ, Lee J, Zhang ZY, et al. Callicarpa japonica Thunb. attenuates cigarette smoke-induced neutrophil inflammation and mucus secretion. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;175:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dharwal V, Naura AS. PARP-1 inhibition ameliorates elastase induced lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;150:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Zhan B. The effects of Ang-1, IL-8 and TGF-β1 on the pathogenesis of COPD. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:1155–1159. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucchioni E, Kharitonov SA, Allegra L, Barnes PJ. High levels of interleukin-6 in the exhaled breath condensate of patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2003;97:1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Wang Y, Gao W, Yuan C, Zhang S, Zhou H, Huang M, Yao X. Klotho reduction in alveolar macrophages contributes to cigarette smoke extract-induced inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27890–27900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.655431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JW, Park JW, Kwon OK, Lee HJ, Jeong HG, Kim JH, Oh SR, Ahn KS. NPS2143 inhibits MUC5AC and proinflammatory mediators in cigarette smoke extract (CSE)-stimulated human airway epithelial cells. Inflammation. 2017;40:184–194. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W, Guo Y, Yang H. Platycodin D protects against cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;47:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Tong D, Liu J, Chen F, Shen Y. Oroxylin A attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by activating Nrf2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;40:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Kismali G, Gupta SC. Natural products for the prevention and treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases: Integrating traditional medicine into modern chronic diseases care. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:9837863. doi: 10.1155/2018/9837863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang N, Zhang H, Cai X, Shang Y. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits inflammation and epithelialmesenchymal transition through the PI3K/AKT pathway via upregulation of PTEN in asthma. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:818–828. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo X, Zhang H, Wei X, Shi M, Fan P, Xie W, Zhang Y, Xu N. Aloin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response and apoptosis by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB. Molecules. 2018;23:E517. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mojiri-Forushani H, Hemmati AA, Dehghani MA, Malayeri AR, Pour HH. Effects of herbal extracts and compounds and pharmacological agents on pulmonary fibrosis in animal models: A review. J Integ Med. 2017;15:433–441. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao X, Sun H, Hou A, Zhao Q, Wei T, Xin W. Antioxidant properties of two gallotannins isolated from the leaves of Pistacia weinmannifolia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1725:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S, Wu X, Ji Y, Yang J. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in Pistacia weinmannifolia (Anacardiaceae) Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:7818–7823. doi: 10.3390/ijms12117818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minami K, Nakasugi T, Sun HD, Hou AJ, Ihara M, Morimoto M, Komai K. Isolation and identification of histamine-release inhibitors from Pistacia weinmannifolia J. Pisson ex Franch J Nat Med. 2006;60:138–140. doi: 10.1007/s11418-005-0017-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nukui M, O'Connor CM, Murphy EA. The natural flavonoid compound deguelin inhibits HCMv lytic replication within fibroblasts. Viruses. 2018;10:E614. doi: 10.3390/v10110614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong HJ, Wang ZH, Meng W, Li CC, Hu YX, Zhou L, Wang XJ. The natural compound homoharringtonine presents broad antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo. Viruses. 2018;10:E601. doi: 10.3390/v10110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhanalakshmi C, Manivasagam T, Nataraj J, Justin Thenmozhi A, Essa MM. Neurosupportive role of vanillin, a natural phenolic compound, on rotenone induced neurotoxicity in SH-Sy5y neuroblastoma cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:626028. doi: 10.1155/2015/626028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badr CE, Van Hoppe S, Dumbuya H, Tjon-Kon-Fat LA, Tannous BA. Targeting cancer cells with the natural compound obtusaquinone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:643–653. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moazed F, Burnham EL, Vandivier RW, O'Kane CM, Shyamsundar M, Hamid U, Abbott J, Thickett DR, Matthay MA, McAuley DF, Calfee CS. Cigarette smokers have exaggerated alveolar barrier disruption in response to lipopolysaccharide inhalation. Thorax. 2016;71:1130–1136. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JW, Ryu HW, Park SY, Park HA, Kwon OK, Yuk HJ, Shrestha KK, Park M, Kim JH, Lee S, et al. Protective effects of neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss.) leaf extract against cigarette smoke- and lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40:1932–1940. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuk HJ, Lee JW, Park HA, Kwon OK, Seo KH, Ahn KS, Oh SR, Ryu HW. Protective effects of coumestrol on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via the inhibition of proinflammatory mediators and NF-κB activation. J Funct Foods. 2017;34:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khokhlova ON, Tukhovskaya EA, Kravchenko IN, Sadovnikova ES, Pakhomova IA, Kalabina EA, Lobanov AV, Shaykhutdinova ER, Ismailova AM, Murashev AN. Using tiletamine-zolazepam-xylazine anesthesia compared to CO2-inhalation for terminal clinical chemistry, hematology, and coagulation analysis in mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2017;84:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arras M, Autenried P, Rettich A, Spaeni D, Rulicke T. Optimization of intraperitoneal injection anesthesia in mice: Drugs, dosages, adverse effects, and anesthesia depth. Comp Med. 2001;51:443–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SU, Lee S, Ro H, Choi JH, Ryu HW, Kim MO, Yuk HJ, Lee J, Hong ST, Oh SR. Piscroside C inhibits TNF-α/NF-κB pathway by the suppression of PKCδ activity for TNF-RSC formation in human airway epithelial cells. Phytomedicine. 2018;40:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold R, Rihoux J, König W. Cetirizine counter-regulates interleukin-8 release from human epithelial cells (A549) Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1681–1691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi BS, Kim YJ, Yoon YP, Lee HJ, Lee CJ. Tussilagone suppressed the production and gene expression of MUC5AC mucin via regulating nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway in airway epithelial cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;22:671–677. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2018.22.6.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JW, Park HA, Kwon OK, Park JW, Lee G, Lee HJ, Lee SJ, Oh SR, Ahn KS. NPS 2143, a selective calcium-sensing receptor antagonist inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2017;90:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Lu L, Lu J, Xia J, Lu H, Yang L, Xia W, Shen S. CD200Fc attenuates inflammatory responses and maintains barrier function by suppressing NF-κB pathway in cigarette smoke extract induced endothelial cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma J, Xu H, Wu J, Qu C, Sun F, Xu S. Linalool inhibits cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JW, Seo KH, Ryu HW, Yuk HJ, Park HA, Lim Y, Ahn KS, Oh SR. Anti-inflammatory effect of stem bark of Paulownia tomentosa Steud. in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages and LPS-induced murine model of acute lung injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim Y, Park JW, Kwon OK, Lee JW, Lee HS, Lee S, Choi S, Li W, Jin H, Han SB, Ahn KS. Anti-inflammatory effects of a methanolic extract of Castanea seguinii Dode in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophage cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:391–398. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konrad FM, Bury A, Schick MA, Ngamsri KC, Reutershan J. The unrecognized effects of phosphodiesterase 4 on epithelial cells in pulmonary inflammation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mokry J, Urbanova A, Medvedova I, Kertys M, Mikolka P, Kosutova P, Mokra D. Effects of tadalafil (PDE5 inhibitor) and roflumilast (PDE4 inhibitor) on airway reactivity and markers of inflammation in ovalbumin-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;68:721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding H, Zhang P, Li N, Liu Y, Wang P. The phosphodies-terase type 4 inhibitor roflumilast suppresses inflammation to improve diabetic bladder dysfunction rats. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-2038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rieder F, Siegmund B, Bundschuh DS, Lehr HA, Endres S, Eigler A. The selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor roflumilast and phosphodiesterase 3/4 inhibitor pumafentrine reduce clinical score and TNF expression in experimental colitis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Hao PD, Yang MF, Sun JY, Mao LL, Fan CD, Zhang ZY, Li DW, Yang XY, Sun BL, Zhang HT. The phosphodies-terase-4 inhibitor roflumilast decreases ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017;234:2409–2419. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4631-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasetty G, Papareddy P, Bhongir RK, Egesten A. Roflumilast increases bacterial load and dissemination in a model of Pseudomononas Aeruginosa airway infection. The J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357:66–72. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Liu J, Zhou JS, Huang HQ, Li ZY, Xu XC, Lai TW, Hu Y, Zhou HB, Chen HP, et al. MTOR suppresses cigarette smoke-induced epithelial cell death and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2018;200:2571–2580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meiqian Z, Leying Z, Chang C. Astragaloside IV inhibits cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice. Inflammation. 2018;41:1671–1680. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma C, Ma W. Plantamajoside inhibits :lipopolysaccharide-induced MUC5AC expression and inflammation through suppressing the PI3K/Akt and NF-kappaB signaling pathways in human airway epithelial cells. Inflammation. 2018;41:795–802. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Zheng H, Zhang H, Ma W, Wang F, Liu C, He S. Increased interleukin (IL)-8 and decreased IL-17 production in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) provoked by cigarette smoke. Cytokine. 2011;56:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song JS, Kang CM, Yoo MB, Kim SJ, Yoon HK, Kim YK, Kim KH, Moon HS, Park SH. Nitric oxide induces MUC5AC mucin in respiratory epithelial cells through PKC and ERK dependent pathways. Respir Res. 2007;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H, Yang T, Wang T, Hao N, Shen Y, Wu Y, Yuan Z, Chen L, Wen F. Phloretin attenuates mucus hypersecretion and airway inflammation induced by cigarette smoke. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;55:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee E, Yun N, Jang YP, Kim J. Lilium lancifolium Thunb. extract attenuates pulmonary inflammation and air space enlargement in a cigarette smoke-exposed mouse model. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JW, Bae CJ, Choi YJ, Kim SI, Kwon YS, Lee HJ, Kim SS, Chun W. 3,4,5-trihydroxycinnamic :acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation by Nrf2 activation in vitro and improves survival of mice in LPS-induced endotoxemia model in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;390:143–153. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-1965-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strzelak A, Ratajczak A, Adamiec A, Feleszko W. Tobacco smoke induces and alters immune responses in the lung triggering inflammation, allergy, asthma and other Lung diseases: A mechanistic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:E1033. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15051033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou R, Luo F, Lei H, Zhang K, Liu J, He H, Gao J, Chang X, He L, Ji H, et al. Liujunzi Tang, a famous traditional Chinese medicine, ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced mouse model of COPD. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;193:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park HA, Lee JW, Kwon OK, Lee G, Lim Y, Kim JH, Paik JH, Choi S, Paryanto I, Yuniato P, et al. Physalis peruviana L. inhibits airway inflammation induced by cigarette :smoke and lipopolysaccharide through inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and induction of heme oxygenase-1. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40:1557–1565. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung KH, Beak H, Park S, Shin D, Jung J, Park S, Kim J, Bae H. The therapeutic effects of tuberostemonine against cigarette smoke-induced acute lung inflammation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;774:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Victoni T, Gleonnec F, Lanzetti M, Tenor H, Valença S, Porto LC, Lagente V, Boichot E. Roflumilast N-oxide prevents cytokine secretion induced by cigarette smoke combined with LPS through JAK/STAT and ERK1/2 inhibition in airway epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jung KH, Kil YS, Jung J, Park S, Shin D, Lee K, Seo EK, Bae H. Tuberostemonine N, an active compound isolated from Stemona tuberosa, suppresses cigarette smoke-induced sub-acute lung inflammation in mice. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee KH, Lee J, Jeong J, Woo J, Lee CH, Yoo CG. Cigarette smoke extract enhances neutrophil elastase-induced IL-8 production via proteinase-activated receptor-2 upregulation in human bronchial epithelial cells. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:79. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0114-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mcguinness AJ, Sapey E. Oxidative stress in COPD: Sources, markers, and potential mechanisms. J Clin Med. 2017;6:E21. doi: 10.3390/jcm6020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JW, Park HA, Kwon OK, Jang YG, Kim JY, Choi BK, Lee HJ, Lee S, Paik JH, Oh SR, et al. Asiatic acid inhibits pulmonary inflammation induced by cigarette smoke. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;39:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai B, Gan X, He J, He W, Qiao Z, Ma B, Han Y. Morin attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation through inhibition of PI3K/AKT/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;63:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo F, Liu J, Yan T, Miao M. Salidroside alleviates cigarette smoke-induced COPD in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;86:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.