Abstract

Introduction:

A comprehensive knowledge of the natural history of UC helps understand disease evolution, identify poor prognostic markers and impact of treatment strategies and facilitates shared decision-making. We systematically reviewed the natural history of UC in adult population-based cohort studies with long-term follow-up.

Materials and Methods:

Through a systematic literature review of MEDLINE through March 31, 2016, we identified 60 studies performed in 17 population-based inception cohorts reporting the long-term course and outcomes of adult-onset UC (n=15,316 UC patients).

Results:

Left-sided colitis is the most frequent location and disease extension is observed in 10–30% patients. Majority of patients have a mild-moderate course, most active at diagnosis and then in varying periods of remission or mild activity; about 10–15% patients experience an aggressive course, and the cumulative risk of relapse is 70–80% at 10 years. Almost 50% patients require UC-related hospitalization, and 5-year risk of re-hospitalization is ~50%. The 5- and 10-year cumulative risk of colectomy is 10–15%; achieving mucosal healing is associated with lower risk of colectomy. About 50% patients receive corticosteroids, though this proportion has decreased over time, with a corresponding increasing in the use of immunomodulators (20%) and anti-TNF (5–10%). While UC is not associated with an increased risk of mortality, it is associated with high morbidity and work disability, comparable to Crohn’s disease.

Conclusion:

UC is a disabling condition over time. Prospective cohorts are needed to evaluate the impact of recent strategies of early use of disease-modifying therapies and treat-to-target approach, with immunomodulators and biologics. Long-term studies from low-incidence areas are also needed.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, population-based, natural history

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disabling inflammatory bowel disease that generally begins in young adulthood and lasts throughout life (1). Although its incidence and prevalence has stabilized in high-incidence areas such as Western Europe and North America, it continues to rise in low-incidence areas such as Eastern Europe, Asia, and much of the developing world (1,2). Besides significantly impacting quality of life and work productivity due to debilitating symptoms, UC is also associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) (1,3,4).

A detailed knowledge of the natural history of UC is essential to understand disease evolution, evaluate the impact of treatment strategies, identify predictors for disabling disease, and provide comprehensive information to patients to facilitate shared decision-making (5,6). In contrast to randomized controlled trials that evaluate specific interventions in a limited set of highly selected patients, over a short pre-defined period, population-based observational cohort studies evaluate an entire population in defined geographic area over an extended period of time. They are ideal to inform natural history of disease, and also avoid selection biases associated with referral center cohort studies (5,7,8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

We conducted a systematic literature search of English and non-English language publications in MEDLINE (source PUBMED, 1935 to March 31, 2016) to identify published population-based studies in patients with UC. We searched for the following terms: (“Inflammatory bowel diseases” OR “ulcerative colitis”) AND (“natural history” OR “population-based” OR “long-term outcome” OR “long-term follow-up” OR “inception cohort” OR “relapse” OR “disease activity” OR “extra-intestinal manifestations” OR “corticosteroids” OR “immunosuppressants” OR “anti-TNF” OR “surgery” OR “colectomy” OR “mortality” OR “cancer” OR “hospitalization” OR “predictors”). A single reviewer screened and identified relevant studies for inclusion, following an a priori established protocol. Additionally, a recursive search of relevant systematic reviews was also performed. The reference lists of relevant articles were also reviewed. Data extraction was carried out using a standardized data collection form, by a single reviewer and confirmed by a second reviewer independently.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included only population-based inception cohort studies of patients with adult-onset UC (≥18y at diagnosis), based on standard clinical, endoscopic and/or histologic criteria through medical record review, with minimum 1 year follow-up, describing the natural history of UC in terms of the following outcomes: disease phenotype, disease activity, complications, disease-related medications, malignancies, morbidity, mortality and/or extra-intestinal complications.

We excluded the following studies: (i) reporting only incidence and/or prevalence of UC, (ii) reporting phenotype, disease complications and/or treatment only at time of diagnosis, (iii) population-based studies that relied on administrative codes for UC diagnosis, without medical record review, (iv) reporting only on IBD, without separate data on UC per se, (v) non-inception cohort studies, which included patients with prevalent UC, and (vi) studies focused on patients with pediatric-onset (<18 years) or elderly-onset (>60 years) UC. Often, one population-based cohort reported several pertinent outcomes, in which case we only included the most recent study with unique outcomes, with the longest follow-up.

Outcomes of Interest

To comprehensively describe natural history of UC, we studied several UC-related outcomes including: (a) disease phenotype (including disease location, proximal extension and change in diagnosis); (b) disease activity and complications (including rates of relapse, hospitalization, surgery and post-operative complications); (c) use of UC-related medications (including 5-aminosalycilate [5-ASA], corticosteroids, immunomodulators [IM] and anti-tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α agents); (d) malignancy (including CRC and extra-intestinal cancers); (e) morbidity and mortality; and (f) extra-intestinal complications (including extra-intestinal disease manifestations, anemia, osteoporosis, venous and arterial thromboembolic events). The Montreal classification was used to classify and compare the phenotype between the various studies. When data were available, we attempted to compare and contrast differences in disease course between patients diagnosed in the pre-biologic (before 2005) and biologic era (after 2005). Additionally, we systematically reviewed clinical, biochemical and/or endoscopic predictors of natural history of UC.

Outcomes at different time points were generally reported in studies either as point prevalence (at a particular time point), or as cumulative probability (over a particular time period). Due to differences in reporting patterns, we opted not to perform a meta-analysis, but instead systematically reported these findings using median and interquartile range (IQR) or range or as preferred summary measures.

RESULTS

Through a systematic literature review, we identified 60 studies reporting on 17 population-based cohorts. Key characteristics of these cohorts and corresponding studies are detailed in Table 1. These included 12 European cohorts, two North-American cohorts and two Asia-Oceania cohorts. Patients were recruited from 1940 to 2014. Sample sizes of these studies ranged from 63 to 3117 patients (total 15,316) and median follow-up ranged from one to 20 years. Salient aspects of study methodology of each population-based cohort are detailed in Supplementary Table 1. Main results of each evaluated outcome are summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 17 population based cohorts included. Y, year.

| Cohort | Country | Study period and follow-up | UC Population | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multicentric European (EC-IBD) | Greece, Israel, Italy, Spain, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway | Diagnosis between 1991 and 1993; follow-up ranging from 4 to 10 y | 328 to 781 | 9,19, 25,38,57,64,73 |

| Copenhagen County | Denmark | Diagnosis ranging from 1962 to 2005; follow-up ranging from 1 to 19 y | 87 to 1160 | 10,23,24,26,43 |

| North-Jutland County | Denmark | Diagnosis between 1978 and 2002; follow-up: 15 y | 1575 | 30 |

| IBSEN cohort | Norway | Diagnosis between 1990 and 1993; follow-up ranging from 5 to 20 y | 328 to 519 | 15,18,36,37 54,56,58,65,68 |

| Veszprem province | Hungary | Diagnosis between 1974 to 2012; follow-up ranging from 5 to 13 y | 220 to 1060 | 13,27,33,44,74,76 |

| Malmo | Sweden | Diagnosis between 1958 and 1982, median follow-up: 15 y | 471 | 22,32,75 |

| Stockholm county | Sweden | Diagnosis between 1955 and 1984; follow-up ranging from 13 to 16.5 y | 1547 to 1586 | 17,28,47,63 |

| Uppsala Region | Sweden | Cohort 1.Diagnosis between 1922 and 1983 Cohort 2. Diagnosis between 2005 and 2009; follow-up ranging from 1 to 11 y | 496 to 3117 | 17,21,41,69 |

| Florence Area | Italia | Diagnosis between 1978 and 1992; follow-up ranging from 11 to 15 y | 689 | 48,60 |

| Dutch IBD-South Limburg cohort | The Netherlands | Diagnosis between 1991 and 2010; follow up ranging from 3 to 17 y | 368 to 1161 | 16,35,52,59 |

| Area of Tampere University Hospital | Finland | Study period between 1986–2007 (diagnosis period not defined); follow-up of 13y | 1254 | 46,61 |

| Olmsted County | USA | Diagnosis ranging from 1940 to 2011; follow-up ranging from 1 to 21 y | 63 to 462 | 12,40,45,49,62,66,67,71 |

| Manitoba IBD cohort | Canada | Diagnosis after 1995; follow-up up to 12.3 y | 45 to 158 | 51,55,61 |

| Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiology Study | China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Macau, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Australia | Diagnosis between 2011 and 2013; follow-up 1.5 y | 222 | 14 |

| Barwon area | Australia | Diagnosis between 2007–2008 and 2010–2013; follow-up of 1.5 y | 96 | 11 |

| ECCO-EPICOM cohort | European Multicentric (14 countries, 31 centers) | Diagnosis in 2011, follow-up of 1 y | 575 to 710 | 20,53 |

| Oberpfalz, Bavaria | Germany | Diagnosis between 2004 and 2009, follow-up > 1 y | 90 | 70 |

Table 2.

Risk of disease extension, relapse, colectomy and hospitalizations in population based studies.

| Disease extension (1) | Relapse/Disease Activity | Colectomy | Hospitalization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBSEN | E1 to E2: 28%, E1 to E3: 14%, E2 to E3: 21% at 10y |

- Relapse: 83% by 10y - Disease course: remission/mild severity after initial period of high activity 55%, chronic intermittent symptoms 37%, chronic continuous symptoms 6% and increase activity after period of low activity 1 % |

5%, 9.5% and 11% by 2, 10 and 20 y | - |

| Copenhagen | E1 to E2: 30% E1 to E3: 16% E2 to E3: 34% Overall extension by 7.5y: 30% |

Indolent course 13%, moderate 73% and aggressive 14% | 24% by 10y (1963–1993), 10% by 5y (2003–2004) |

- |

| EC-IBD cohort | Disease location at 10y: E1 22%, E2 53%, E3 24% | Relapse: 67% by 10 y | 8.5% by 10y | - |

| Hungary/Veszprem | Extension by 1, 3, and 5 y: 2.9%, 9.4%, and 12.7%. Disease location at 7y: E1 28%, E2 44%, E3: 28% |

- | 0.5%, 1.8%, and 2.8% by 1, 3, and 5y | 29%, 54% and 66% by 1, 5 and 10y |

| Asia-Pacific cohort | Overall extension: 11.5% (by 1.5y) | During 1st y: remission (UC-SCCAI of ≤ 2) 65%, mild to moderate disease (3–4) 18%, and severe disease (≥5) 17% | 1.6% (Asia) and 5.9% (Australia) by 1.5y | - |

| Malmo cohort | - | Relapse: 70% by 10y | 23% by 15y | - |

| Uppsala | - | During 1st year: Relapse 43%, chronic activity 5%, remission 50% | 16%, 20% and 25% | - |

| Stockholm County | - | - | by 10, 20 and 30y | - |

| South-Limburg | - | - | 3%, 6%, and 7% by 1, 3, and 5 y | - |

| Olmsted | - | - | 3.8%, 13%, 19%, and 25% by 1, 5, 10 and 20y | 29%, 39%, 49%, 52% by 5, 10, 20 and 30y |

| EPICOM | - | Remission: 11% at diagnosis, 73% at 1 y | 3% by 1 y | 13% by 1 y |

| Barwon | - | - | 6% at 1y, 13%by5y | 23% by 5y |

| North Jutland County | - | - | 1991–1997: 4.1%, 5.6%, and 7.5% by 1, 2, 5y, 1998–2005: 0.9%, 2.1%, and 5.7%, 2006–2010: 1.0%, 2.8%, and 4.1% | 1991–1997: 12%, 17%, and 22%, by 1, 2, 5y 1998–2005: 8.6%, 12%, and 19.5% 2006–2010: 8.7%, 11%, and 18% |

(1) According to the Montreal classification

Table 3.

Exposure to UC-related medications.

| Cohort | No medications | 5-ASA | Steroids | Immunosuppressants | Anti-TNFs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBSEN | 3% by 1y (CP) | - | 13%, 41 % and 48% by 1, 5 and 10y (CP of second course) | 7% by 10y (CP) | - |

| Copenhagen | - | 87% by 15y(CP), with no change over time (1962–2004) 78% by 1y, 85% by 5y (CP) (2003–2004) | 50% by 15y (CP) with no change over time (1962–2004) 43% by 1y, 59% by 5y (CP) (2003–2004) | 27% by 7 y (CP) (2003–2004) | 4% at 5y and 6% by 7y (CP) (2003–2004) |

| EC-IBD cohort | 11 to 35% (prevalence at 4y) | - | - | - | - |

| Veszprem | - | - | 40% by 7 y (CP) | 17% by 7y (CP) | 7.5% by 7y (CP) |

| Asia-Pacific cohort | - | 88% by 1.5 y (CP) | 25% by 1.5y (CP) | 13% by 1.5y (CP) | 1% by 1y (CP) |

| Uppsala | - | 97% by 1 y (CP) | 64% by 1 y (CP) | 12% by 1y (CP) | 5% by 1y (CP) |

| South-Limburg | 26%, 32% and 40% by 1, 5 and 11 y (prevalence) | 73%, 65% and 60% at 1, 5 and 11 y (prevalence) | 20%, 18% and 12% by 1, 5 and 11 y (prevalence) | 1991–1997: 8% by5y (CP) 1998–2005: 23% by 5y (CP) 2006–2010: 23% by 5y (CP) | 1998–2005: 5% by 5y (CP) 2006–2010: 10% by 5y (CP) |

| EPICOM | - | 97% by 1 y (CP) | 46% by 1y | 20% by 1y | 5% by 1y (CP) |

| Barwon | - | - | 63% by 1.5y | 19% by 1.5y | 2% by 1.5y (CP) |

Abbreviations: 5ASA, 5 aminosalycilic acid; Y, years; CP, cumulative probability

Table 4.

Risk of extra-intestinal manifestations, colorectal cancer, extra-intestinal cancer and mortality in population based studies.

| Cohort | EIMs | Colorectal Cancer | Extra-digestive cancer | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBSEN | Peripheral arthritis: 11%, AS: 2.6% by 6y | - | - | Overall: HR 1.1 (95 CI%, 0.9–1.4) | |

| Copenhagen | - | Overall: SMR 1.1 (95% CI, 1.0–1.2), 0.4%, 1.1%, and 2.1% by 10, 20 and 30y | Overall cancer: SMR 0.9 (95% CI, 0.7–1.1) Melanoma: SMR 3.4 (95% CI, 1.4–7.1) | Overall: SIR 1.1 (95% CI, 1.0–1.2) | |

| EC-IBD cohort | 10% by 10y. Articular 8%, Iridocyclitis/Uveitis 0.6%, cutaneous 1.3%, PSC 0.6%. | - | 3.3% by 10 y | Overall: SMR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9–1.4), Pulmonary diseases: SMR 2.0 (95% CI, 1.0–3.6), Cancer: SMR 1.0 (95% CI, 0.6–1.6), CV: SMR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.7–1.5), GI diseases: SMR 2.0 (95% CI, 0.7–4.7) | |

| Hungary/Veszprem | 17% at 7y | - | NHL: SIR 1.35 (95% CI, 0.34–5.42), NHL in male: SIR 2.4 (95% CI, 0.77–7.47) | 0.6%, 5.4%, 7.5% by 10, 20 and 30y. Disease Duration >1 y: OR 14.3 (95% CI, 1.8–110.5), Chronic continuous disease: OR 6.4 (95% CI, 1.9–21.6), Extensive vs left-sided colitis: OR 5.3 (95% CI, 1.7–16.4), PSC: OR 27.1 (95% CI, 7.9–92.0) | |

| Malmo cohort | - | Overall SIR 2.1 (95% CI, 1.0–4.1) | - | - | |

| Uppsala | - | Overall: SIR 5.7 (95% CI, 4.6–7.0), Proctitis: SIR 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8–3.2), LSC: SIR 2.8 (95% CI, 1.6–4.4), Age <15 y at diag: SIR 4.0 (95% CI, 2.07–7.85), Pancolitis: SIR 14.8 (95% CI, 11.4–18.9) | - | NHL: SIR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.6–1.8), HL: SIR 0.4 (95% CI, 0.0–2.2), Overall leukaemia: SIR 2.3 (95% CI, 1.4–3.7), Acute myeloid leukaemia: SIR 2.5 (95% CI, 1.2–4.8) | - |

| Stockholm County | - | Proctitis: SIR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.7–1.7), LSC: SIR 1.4(95% CI, 1.1–1.9), Pancolitis: SIR 1.4 (95% CI, 1.0–1.9) | Extra-colonic cancer: SMR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.9–1.3), Hepato-Biliary (men): SMR 6.0 (95% CI, 2.8–11.1), Pulmonary: SMR 0.3 (95% CI, 0.1–0.9) | Overall: SMR 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2–1.5), Cancer: SMR 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9–1.6), CRC: SMR 2.9 (95 CI%, 1.6–4.7), Respiratory disease: SMR 1.9 (95% CI, 1.1–2.9), Liver disease: SMR 4.8 (95% CI, 2.1–9.5) | |

| South-Limburg | 7% at 7y | - | - | Overall: SMR 0.9 (95% CI, 0.7–1.2), GI causes: SMR 3.4 (95% CI, 1.4–7.0), GI causes (Women): SMR 8.6 (95% CI, 2.8–20.0), GI causes (<19y) SMR 537.3 (95% CI, 7.0–2989) | |

| Olmsted | Cumulative incidence of SpA: 14% at 20y | Overall SIR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.4–2.4), Proctitis SIR 0 (95% CI, 0.0–3.5), Pancolitis SIR 2.4 (95% CI, 0.6–6.0) | Overall cancer: 5% by 10 years, Overall cancer: SIR 1.1 (95% CI, 0.8–1.4), Overall cancer (women): SIR 1.6 (95% CI, 1.1–2.3), Overall cancer (men): SIR 0.9 (95% CI, 0.6–1.2), Hemato malignant tumors: SIR 2.7 (95% CI, 1.2–5.3), Melanoma: SIR 2.0 (95% CI, 0.7–4.4), Hepatobiliary: SIR 11.4 (95% CI, 2.4–33.2), Lung: SIR 0.3 (95% CI, 0.1–0.9) | Overall: SMR 0.8 (95% CI, 0.6–1.0), GI diseases: SMR 2.0 (95% CI, 0.8–4.4), GI cancer: SMR 2.2 (95% CI, 0.7–5.2), CV Death: SMR 0.6 (95% CI, 0.4–0.9) | |

| EPICOM | - | - | - | 0.3% at 1y | |

| North Jutland County | - | SIR 0.8 (95% CI, 0.5–1.4). Young age at diagnosis SIR 17.1 (95% CI, 0.4–95.1) | Overall cancer: SIR 1.1 (95 % CI, 0.9–1.2), Prostate: SIR 1.8 (95% CI, 1.1–2.7) | - | |

| Florence | - | Overall: SIR 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8–3.2), Extensive colitis: SIR 3.1 (95% CI, 1.5–5.8) | Overall cancer: SIR 1.0 (95% CI, 0.7–1.3), Respiratory tract: SIR 0.2 (95% CI, 0.0–0.8) | Overall: SMR 0.7 (95% CI, 0.6–0.9), CV: SMR 0.7 (95% CI, 0.5–1.0), Overall cancer: SMR 0.7 (95% CI, 0.5–1.0), Lung cancer mortality: SMR 0.3 (95% CI, 0.1–1.0), CRC: SMR 1.3 (95% CI, 0.3–3.2), GI disease: SMR 1.6 (95% CI, 0.8–2.8) | |

| Area of Tampere University Hospital | - | Overall: SIR 2.0 (95% CI, 1.1–3.3), Proctitis: SIR 0.0 (CI 95%, 0.0–2.8), Left sided colitis: SIR 1.8 (95% CI, 0.7–3.8), Pancolitis: SIR3.1 (95% CI, 1.5–5.8) | - | Overall: SMR 0.9 (95% CI, 0.8–1.1), CV: SMR 1.0 (95% CI, 0.8–1.4), CRC: SMR 1.8 (95% CI, 0.7–3.7) | |

Abbreviations: Dis, disease; Diag, diagnosis; AS, Ankylosing Spondylitis, SpA, Spondylarthropathy; EN, Erythema Nodosum; PG, Pyoderma Gangrenosum; PSC, Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; SIR; Standardized Incidence Ratio; SMR; Standardized Mortality Ratio; OR, Odds Ratio; HR, Hazard Ratio; PSC, Primary sclerosing cholangitis; NHK, Non Hodgkin Lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin Lymphoma; LSC, Left Side Colitis; CV, Cardiovascular; GI, Gastrointestinal.

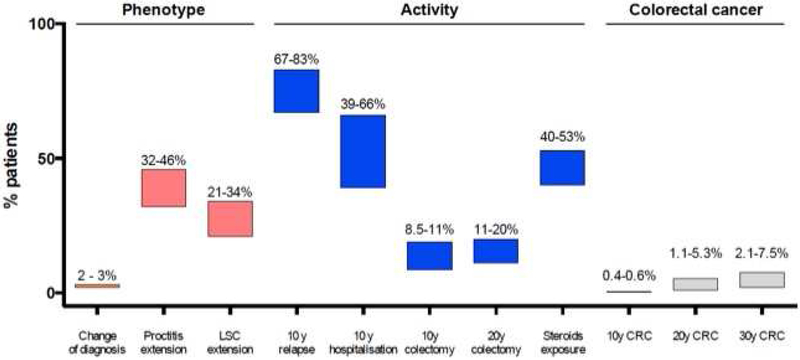

Figure 1.

Cumulative risk of main outcomes on disease phenotype, disease activity and colorectal cancer in population-based studies.

Abbreviations: LSC, left side colitis; CRC, colorectal cancer; y, year.

I. Disease Phenotype

Disease Extension

At diagnosis, the majority of patients had left-sided colitis (median 40.1%; IQR, 32.6–44.6); 30.5% (29.8–32.6) and 29.4% (25.3–34.7) were diagnosed with extensive colitis and proctitis, respectively (9–17). Overall rates of disease extension were comparable across cohorts, regions, and over time (including the pre-biologic and biologic era) (Table 2). Rate of progression from proctitis to left-sided colitis was 28–30%, and to extensive colitis was 14–16%; rate of progression from left-sided colitis to extensive colitis was 21–34% (9,10,18). Overall rates of progression ranged from 12–30%, with cumulative 5-year risk of progression being approximately 13% (10,13,14). At the end of follow-up, left-sided colitis (44–53%) was the most common site of disease involvement, followed by extensive colitis (24–28%) and proctitis (22–28%). Extra-intestinal manifestations (EIMs) (odds ratio (OR), 3.6; confidence interval (CI) 95%, 1.4–9.3), and elevated C-reactive protein both at diagnosis and at 5y of follow-up, were significantly associated with extensive disease (13,15).

Change of diagnosis

In the EC-IBD cohort, the original diagnosis of UC remained unchanged in 98% of cases after 4 years of follow-up (19); in 1% patients, the diagnosis was changed to Crohn’s disease (CD), and in another 1%, to indeterminate colitis. In the South-Limburg cohort, the diagnosis of UC was changed in 3% of patients, after a median follow-up of 7 years (16).

II. Disease Activity and Complications

Disease Relapse

In the 10y follow-up study of the IBSEN cohort, four different profiles of disease activity were reported by patients: remission or mild severity after initial period of high activity (55%), chronic intermittent symptoms (37%), chronic continuous symptoms (6%) and increase activity after period of low activity (1%) (18). In studies evaluating changes in disease activity within the first 1–2 years of diagnosis, most studies observed improvement in disease activity in 50–70% patients (14,20,21). In the Uppsala cohort, 50% patients remained in remission within the first year after initial disease flare, 43% of patients experienced relapse and 5% had chronic symptoms without remission (21). Similarly, in the Asia-Pacific cohort, during the 1-year after diagnosis, 65% patients were in clinical remission (UC Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) ≤2), 18% had mild to moderate disease (SCCAI 3–4), and 17% had severe disease (SCCAI ≥5), respectively (14). On longer follow-up, rates of remission remained stable. In the EC-IBD cohort (19), after 4 years follow-up, half of patients described complete relief of their symptoms. Cumulative risk of relapse ranged from 67% to 83% at 10 years (median, 70.0%; IQR, 68.5–76.5) (19,21,22).

There has been limited comparison of disease activity trends between the pre-biologic and biologic era, though there seems to be a shift towards improved early disease course, perhaps related to availability and early adoption of more effective therapies. In a cohort of patients diagnosed in Copenhagen county between 1962–93, disease course was characterized as indolent, moderate or aggressive in 13%, 73% and 14% of patients, respectively, within the first 5-years of diagnosis; in the same region, in a cohort of patients diagnosed between 2003–04, early disease activity was characterized as mild in 76%, and moderate-to-severe in 24% (23,24).

Young age at disease onset (hazard ratio (HR), 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0–1.6), female sex (HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.7) and high level of education (HR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8) has been associated with disease relapse, while smoking may be protective (HR 0.7; 95%CI, 0.6–0.9) (9,16,21). Conflicting data on the association between serological markers and risk of relapse were observed (25,26) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Predictors of natural history in Ulcerative colitis.

| Outcome | Clinical variables |

|---|---|

| Disease Relapse | Age < 40 years at diagnosis Female sex Extra-intestinal manifestations High level of education Non smoker pANCA + ASCA + |

| Hospitalizations | Extensive disease Need for corticosteroids, azathioprine or anti-TNF Early need for hospitalization |

| Colectomy | Age <40 years at diagnosis Male sex Extensive disease CRP>10 mg/L, ESR>30 mm Absence of mucosal healing |

| Initiation of anti-TNF therapy | Age <40 years |

Abbreviations: HR, Hazard Ratio; OR, Odds Ratio; RR, Relative Risk; CS, Corticosteroids; DIag, Diagnosis, CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ANCA, Perinuclear Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies; ASCA, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiæ anti-body; MH, Mucosal healing.

Hospitalization

Almost half the patients with UC require hospitalization at some point during disease course, with 1-, 5-, 10-year cumulative probabilities ranging from 17–29%, 29–54% and 39–66%, respectively; 10–15% may be hospitalized at time of diagnosis (11,12,20,27). Among patients who are hospitalized once, cumulative probability of re-hospitalization 1-, 5- and 10-years after index hospitalization ranges from 24%, 51–56% and 59–75%, respectively (11,12,20,27). Overall, the rate of hospitalization may be declining; in an Olmsted County cohort, rate of hospitalization declined from 134/1,000 py in 1970–79 to 88/1,000 py from 2000–04 (12).

Disease extent at diagnosis (HR, 1.8, p=0.02), need for corticosteroids (HR, 2.0, p<0.001), immunomodulators (HR, 1.6, p=0.038) and/or anti-TNF agents (HR, 2.3, p<0.001) have been associated with an increased risk of UC-related hospitalization (12,27); early need for hospitalization (<90 days after diagnosis) was an independent predictor for future hospitalization (HR, 1.5; 95%CI, 1.0–2.4) (12).

Surgery

Risk of colectomy in adults with UC has been extensively studied and is summarized in Table 2. In an early report of colectomy from the Stockholm County cohort in patients diagnosed between 1966–1984, cumulative colectomy rate at 5-, 10- and 25y after diagnosis was 20%, 28% and 45%, respectively (28). Subsequent studies have reported lower rates of colectomy, with 1, 5, 10 and 20-y cumulative colectomy rate ranging from 0.5–6%, 3–13%, 8.5–19%, and 11–20%, respectively (10–12,14,17,18,20,23,29–33). A recent meta-analysis of population-based studies observed a cumulative risk of surgery in adults of 4.4%, 10.1%, and 14.6%, respectively 1, 5, and 10 years after UC diagnosis, with a significant decrease over time (34). In a contemporary Copenhagen County cohort of patients diagnosed between 2003–04, cumulative risk of colectomy at 5 years was 10% (23); similarly, in a recently established Oceania cohort, less than 2% of patients in Asia and 6% in Australia underwent a colectomy after median 1.5 year of follow-up (11,14). In the Dutch population-based South Limburg cohort, patients diagnosed with UC between 1991–97 had an early colectomy (within 6 months) rate of 1.5%, compared to a rate of 0.5% in a contemporary cohort from 2006–10; late colectomy rates in these cohorts were similar (1991–97 vs. 2006–10: 4% vs. 3.6%) (35). The indication for colectomy appears to have changed over time. In Olmsted County, among colectomies performed before 1990, 90% were performed for medically refractory disease, 5% for fulminant colitis, and 5% for colorectal neoplasia. In contrast, among surgeries performed after 1990, 56% were performed for medically refractory disease, 26% for fulminant colitis and 12% for colorectal neoplasia. The types of surgery were total protocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis in 54%, total proctocolectomy with end-ileostomy in 33% and subtotal colectomy and ileostomy in 12% (12).

Disease extent consistently influences risk of colectomy (OR 2.2; 95% CI, 1.1–4.3), with significantly higher risk in patients with extensive colitis (10y cumulative risk, 19%), followed by left-sided colitis (8%) and ulcerative proctitis (5%) (16,18,20). Young age (age <40y: OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.3–5.9), male gender (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.3–3.5) and elevated CRP/erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (CRP≥30 mg/l or ESR≥30 mm/h: OR, 3.3, 95% CI 1.7–6.5) at diagnosis have been associated with an increase risk of colectomy (11,12,21). In the IBSEN cohort, patients younger than 40 years with extensive colitis, who were treated with systemic corticosteroids and had ESR≥30 mm/h or CRP≥30 mg/l at diagnosis had a probability of colectomy of 40% as compared to 8% for same age patient with proctitis or left-sided colitis and ESR<30 mm/h or CRP<30 mg/l at diagnosis (36). In a Norwegian cohort, achieving endoscopic mucosal healing within one year of disease onset was associated with a 78% lower risk of future colectomy, as compared to continued endoscopic disease activity (RR 0.2, 95% CI, 0.1–0.8) (37). However, the majority of the colectomies occurred during the first 3 months after endoscopic assessment, which limit the interpretation of long-term impact of MH in UC.

Postoperative complications

In the EC-IBD cohort, 32% of patients operated on between 1993 and 2004 developed postoperative complications without difference between acute and elective surgery, and 6% died postoperatively (38). Among the 33 deaths observed in the 1962–1987 cohorts from Copenhagen, 19 (58%) resulted from postoperative complications. A meta-analysis of both administrative and inception population-based studies recently observed a pooled mortality rate of respectively 0.7% and 5.3% for elective and emergent surgery, respectively without significant decrease over time (39).

In summary, the majority of patients with UC have a mild-moderate course, generally most active at diagnosis and then in varying periods of remission or mild activity; about 14–17% of patients may experience an aggressive course. Median cumulative risk of relapse is 70.0% (IQR, 68.5–76.5) by 10 years. Almost half the patients require UC-related hospitalization at some point during disease course, and among those hospitalized once, 5-year risk of re-hospitalization is about 50%. The 5- and 10-year cumulative risk of surgery is 10–15%, and though rates of early colectomy have declined, long-term colectomy rates have generally remained stable over time; contemporary cohorts with early use of biologic agents are lacking.

III. UC related medications

No IBD-medications

In the Uppsala inception cohort, 97% patients were exposed to either 5-ASA, or steroids during the first year after diagnosis (21). The prevalence of no IBD medications 1, 5 and 11 years after diagnosis was 26%, 32% and 40%, respectively, in the Dutch-SL cohort (16).

5-aminosalcylic acid

Approximately 88–97% patients received 5-ASA within 1 year of diagnosis (14,20,21) (Table 3). On long-term follow-up, 60–87% patients continued 5-ASA use at 11–15 years after diagnosis, without significant change over time (10,16,23).

Corticosteroids

In the Copenhagen Cohort, 50% patients received corticosteroids after a median follow-up of 15 years (23). Among patients with corticosteroid exposure, cumulative rates of second course of CS at 1-, 5- and 10 years was 13%, 41% and 48%, respectively, in the IBSEN cohort; however, the likelihood of steroid exposure decreases with time since UC diagnosis, with reported 1-, 5- and 11-year point prevalence of corticosteroid use of 20%, 18% and 12%, respectively (16). Implications and outcomes of corticosteroid exposure were studied in the Olmsted County cohort, in a prebiologic era. Faubion and colleagues observed that within 30 days of a course of corticosteroids, 54% patients achieved complete remission, 30% were in partial remission, and 16% were non-responders; one year after initiation of corticosteroids, 49% were in sustained clinical remission, 22% were steroid-dependent, and 29% underwent colectomy (40). Among patients diagnosed between 2003–2004 in the Copenhagen County cohort, steroid dependency was observed in 9% of patients after a follow-up of 5 years. The risk of corticosteroid exposure appears to be decreasing in the biologic era. In the same Copenhagen county cohort, exposure to corticosteroids was significantly higher in patients diagnosed between 1962–87 (53%) and 1991–93 (56%) as compared to 2003–04 (40%) (23). However, 5 years later 59% of patients were exposed to corticosteroids (10).

Extensive colitis and EIMs (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.7–5.5) have been significantly associated with need for corticosteroids (13,16).

Immunomodulators

The use of immunomodulators has increased incrementally since 1990s (10,16). In the pre-biologic era, the point prevalence of immunomodulator medications use at 1, 5 and 10 years after diagnosis was 5%, 12% and 12%, respectively (16). In contemporary cohorts, immunomodulator use has increased 2–3-fold, with reported use in 11–20% at 1 year, and 17–27% by 7 years (10,11,14 20,23,27). In the Dutch-SL cohort, the 5-year cumulative probability of using thiopurines increased from 8% in patients diagnosed between 1991–1997 to 23% in patients diagnosed between 1998–2010. Over time, thiopurines have also been initiated earlier during disease course, from median 23 months (1991–1997) to 10 months after UC diagnosis (2006–2010) (35). About 10% experienced adverse events after at a median of 1 month (range 1–24 months) (11). Likelihood of exposure to immunomodulator is significantly higher in patients with extensive colitis (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.7–4.9) and EIMs (OR 2.6; CI 95%, 1.4–4.9) (14,13).

Anti-TNF

Limited studies have evaluated patterns of anti-TNF use in population-based cohorts. In contemporary cohorts, at 1 year, 1–5% patients were treated with anti-TNF (11,14,20,21). More long-term results are available from the Copenhagen County and Hungary, where 4% patients have been treated with anti-TNF at 5 years and 6–7% at 7y (10,27). In the Dutch-SL cohort, the cumulative 5-year probability of anti-TNF exposure increased from 4% in patients diagnosed between 1998–2005, to 10% in patients diagnosed between 2006–2010, and the median time to initiation decreased from 44 to 12 months; 37% received combination therapy with azathioprine (35).

In the EPICOM cohort, most of the patients treated with anti-TNF (65%) had extensive colitis. Young age at time of disease onset (<40y: HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.1–5.7) was associated with anti-TNF exposure (20).

To summarize, almost all patients with UC are exposed to 5-ASA within 1 year of diagnosis, though 30–40% are not on 5-ASA on long-term follow-up. About 50% of patients eventually receive a treatment course of corticosteroids, although this proportion has decreased over time, with a corresponding increasing in the use of immunomodulators (20% patients), and anti-TNF (5–10%).

IV. Malignancies

Colorectal cancer

Since the recognition of increased risk of CRC in patients with UC in a Swedish population-based cohort (standardized incidence ratio (SIR) 5.7; 95% CI, 4.6–7.0) (41), several studies have confirmed increased CRC rates in UC patients, with a pooled SIR of 2.4 (95% CI, 2.1–2.7) and an average 1.6% patients are diagnosed with CRC during 14 years of follow-up (42) (Table 4). Cumulative probability of CRC at 10, 20, and 30 years after UC diagnosis was 0.4–0.6%, 1.1–5.4%, and 2.1–7.5%, respectively (43,44). This risk is increased in patients with pancolitis (SIR, 2.4–14.8) and left-sided colitis (SIR, 1.4–2.8), but not in patients with proctitis (41,45–47). Young age at diagnosis, male sex, extensive colitis, disease duration and concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis have been consistently identified as risk factors of CRC. The risk of CRC was similar in users and non-users of 5-ASA and thiopurines in Denmark (30). One population-based study suggested that CRC complicating UC is more aggressive than sporadic CRC; unadjusted overall mortality (47/100,000py) was almost 2-fold higher as compared to patients with sporadic CRC (standardized mortality ratio, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4–2.2) (17).

Extra-intestinal cancer

Population-based studies have shown no consistent increase in the risk of overall- or extra-intestinal cancers in patients with UC, as compared to the general population (Table 4) (30,43,47–49). On meta-analysis of population-based inception cohorts, patients with UC were noted to have a lower risk of lung cancer (SIR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.7) and overall cancers of the respiratory tract (SIR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5 – 1.0), and a higher risk of liver and biliary tract cancers (SIR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.6–4.2), and leukemia (SIR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3–3.1) (50). No consistent increase in the risk of prostate or cervical cancer, melanoma or Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was observed (50). In the Danish North-Jutland cohort, overall cancer risk was similar among women and men, across age groups, across disease localization, among smokers and non-smokers, and among ever users and never users of 5-ASA and thiopurines (30).

V. Morbidity and Mortality

Patients reported outcomes, quality of life and disability

In the Manitoba cohort, patients with UC reported high rates of fatigue and sleep difficulties, particularly those with active symptoms (67% and 72%, respectively), as compared to those with inactive UC (30% and 57%, respectively), and these rates were not significantly different than in patients with CD (51). This high rate of fatigue was confirmed in the Dutch-SL cohort, and was associated with lower quality of life. Disease activity, anemia and female sex were independent determinants of fatigue (52). Health-related quality of life scores generally improved from diagnosis to 1-year of disease, and baseline high Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire scores, limited disease extent, absence of EIMs, non-receipt of biologic therapy and no need for surgery, were predictive of superior health-related quality of life on follow-up (53,54).

Overall disability burden was lower in patients with UC, as compared to patients with CD, and was associated with long-term active disease, but not IBD-related surgeries or hospitalizations (55). In a contemporary Australian cohort, 25% patients were classified as having disabling disease defined by at least one of the following criteria present at 12 months: >2 courses of steroids, further hospitalization after diagnosis, ongoing active disease, or colectomy (11). Work disability, defined as all patients who had applied or had been granted for rehabilitation benefits, was evaluated in the IBSEN cohort. Patients with UC had 1.8 times higher risk of work disability (95% CI, 1.4–2.3) as compared to general population, and was comparable to that seen in patients with CD (56). Male sex, disease relapse, need for corticosteroids or surgery within one year of disease onset, and elevated CRP or ESR have been associated with work disability (11,56).

Mortality

UC has not been associated with an increased mortality, as compared to the general population, except in one cohort (23, 57–62). When assessing the specific causes of death, UC may be associated with increase in the risk of gastrointestinal-related mortality, partly attributed to an increased mortality from liver diseases, and inconsistent increase in risk of CRC-related mortality, and to respiratory-related mortality primarily due to asthma-related deaths, despite a decrease in risk of respiratory tract cancers. Overall, there has been no increase in risk of cancer-related or cardiovascular mortality (47,57,59–63).

VI. Extra-intestinal Complications

Extra-intestinal Manifestations

Overall risk of EIMs in patients with UC ranges from 7–17%, probably lower as compared to patients with CD, and approximately 1% patients may present with EIMs before UC diagnosis (13,16,64). Articular manifestations are the most frequently observed EIMs (8%), including peripheral arthritis (5.5%), and ankylosing spondylitis (1%), followed by cutaneous EIMs (1.3%), PSC (0.6%) and ocular manifestations (0.6%) (64,65). The cumulative incidence of spondyloarthropathy was 5%, 14%, and 22% at 10, 20 and 30y after UC diagnosis (66) and in the IBSEN cohort, 11% of UC patients experienced peripheral arthritis within the 6y after diagnosis, with 20% of these being observed prior to UC diagnosis (65). Interestingly, risk of hidradenitis suppuritiva may be 6-fold higher in patients with UC, as compared to the general population (67). Patients with left-sided and extensive may be at increased risk of EIMs as compared to patients with proctitis (15% vs 6%) (64).

Other Extra-intestinal Complications

Approximately 20–24% of patients with UC are anemic at diagnosis, including 8% with severe anemia (<10g/dl). This rate generally decreases on follow-up, to 8–10% within 5 years, and 7% by 10 years (68,69,70), although in a Hungarian cohort, prevalence of anemia was higher at 30% after 7 years of disease (13). Disease extent, and high disease activity (based on elevated CRP or ESR, or need for corticosteroids) were significantly associated with anemia (68,69).

In both Manitoba and Olmsted cohorts, there was no significant increase in risk of fractures in patients with UC, and patients had normal hip and lumbar spine bone density scores (71,72).

Incidence rate of venous thromboembolism ranged from 1.1–2.0/1000 py, with a 5- and 10- cumulative probability of 0.8% and 1.2%, respectively, may be higher in patients with UC, as compared to patients with CD (73,74). High disease burden and disease activity, as measured by presence of extensive colitis (OR 3.3; 95% CI, 1.1–9.4), fulminant colitis (OR 4.2; 95%CI, 1.3–13.5), and need for corticosteroids (OR 3.0; 95%CI, 1.0–8.9), as well as smoking (OR 3.5; 95%CI, 1.1–10.5) were significantly associated with risk of venous thromboembolism (73,74). No population-based data on risk of arterial cardiovascular events was available from inception cohorts.

DISCUSSION

We have systematically summarized the current knowledge on the natural history of UC from 17 population-based inception cohorts reported in 60 studies, across multiple domains including disease extent, activity, EIMs, medication use, requirement for surgery, etc. We observed that the diagnosis of UC generally remains stable over time, and infrequently evolves into CD (<5%). Though left-sided colitis is most frequently observed at diagnosis in approximately 40% patients, about 10–30% of patients may develop proximal extension on follow-up. The majority of patients have a mild-moderate course, generally most active at diagnosis and then in varying periods of remission or mild activity; about 10–15% of patients may experience an aggressive course, and the cumulative risk of relapse is 70–80% at 10 years. Almost half the patients require UC-related hospitalization at some point during disease course. The 5- and 10-year cumulative risk of surgery in patients with UC is 10–15%, and though rates of early colectomy have declined, long-term colectomy rates have generally remained stable over time. We observed that almost all patients with UC are exposed to 5-ASA within 1 year of diagnosis, though 30–40% are not on 5-ASA on long-term follow-up. About 50% of patients receive corticosteroids, though this proportion has decreased over time, with a corresponding increasing in the use of immunomodulators (20%), and anti-TNF (5–10%). Approximately 1.5% patients are diagnosed with colorectal cancer after 15 years of follow-up, particularly those with young age at disease onset, extensive disease and concomitant PSC. Ulcerative colitis is not associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. However, gastrointestinal-specific mortality, but not cancer-specific mortality, may be increased. Ulcerative colitis is associated with high morbidity, with high rates of fatigue, inferior health-related quality of life, and high disability, generally comparable to levels observed in patients with CD. Consistent predictors of aggressive UC disease course are young age at diagnosis, extensive disease, early need for corticosteroids and elevated biochemical markers; achieving mucosal healing early may be strongly associated with a decreased risk of future colectomy. We note that these variables are all easily determined and monitored with electronic medical records, and create a future opportunity to risk stratify patients and focus health resource utilization on the subgroup of patients at high risk for a worse disease outcome.

Knowing the UC natural history and identified predictors of disabling disease is essential to initiate personal therapeutic strategy according to risk stratification. High-risk patients may benefit to early combination therapy and low risk patients to rapid step-up therapy (77). However, we identified several areas of knowledge gap on natural history of UC. First, while several risk factors associated with a generally aggressive disease course have been identified, an impact of treatment based on early stratification of high- and low-risk patients on the natural history of disease is not well studied. Second, there is limited data on the course and outcomes of UC in newly industrialized nations and Asia-Oceania region; with the creation of recent population-based cohorts, this knowledge is anticipated to increase in the coming years. Third, contemporary population-based cohorts of patients diagnosed in the biologic era are lacking. These may inform us on the population-level impact of paradigm shifts in approach to UC management over the last decade, such as early use of disease-modifying biologic therapy, and treat-to-target strategy. Fourth, slight differences were observed in different outcomes, particularly in risks of surgery and hospitalizations in different cohorts. Whether this is due to differences in medical practices, particularly access of newer therapies, or to true differences in underlying disease behavior and biology in different populations, needs to be explored. With creation of large, collaborative population-based networks, these gaps will be bridged in the coming decade.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Cumulative probabilities of colectomy in population-based studies.

What is current knowledge:

A detailed knowledge of the natural history of ulcerative colitis (UC) is essential to understand disease evolution, evaluate the impact of treatment strategies, and identify predictors for disabling disease.

Population-based observational cohort studies are ideal to inform natural history of disease.

What is new here:

Majority of patients have a mild-moderate course; about 10–15% patients experience an aggressive course, and the cumulative risk of relapse is 70–80% at 10 years.

Almost 50% patients require UC-related hospitalization. The 5- and 10-year cumulative risk of colectomy is 10–15%

While UC is not associated with an increased risk of mortality, it is associated with high morbidity and work disability.

Consistent predictors of aggressive disease course are young age at diagnosis, extensive disease, early need for corticosteroids and elevated biochemical markers; achieving mucosal healing early may be strongly associated with a decreased risk of future colectomy.

Disclosures and conflict of interest:

Dr. Fumery is supported by the French Society of Gastroenterology (SNFGE, bourse Robert Tournut) and received lecture fees/consultant fee from Abbvie, MSD, Takeda and Ferring. Dr. Singh is supported by the NIH/NLM training grant T15LM011271 and the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award and Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of American Career Development Award. Dr. Dulai is supported by the NIDDK training grant 5T32DK007202. Dr Gower has served as speaker for Abbvie France, Ferring International, Janssen International and MSD France. Dr Peyrin-Biroulet has received consulting fees from Abbott, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celltrion, Ferring, Genentech, Hospira, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Mitsubishi, Norgine, Pharmacosmos, Pilege, Shire, Takeda, Therakos, Tillots, UCB and Vifor, and has received lecture fees from Abbott, Ferring, HAC-pharma, Janssen, Merck, Norgine, Therakos, Tillots and Vifor. Dr Sandborn has received grant support from Exact Sciences, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the Broad Foundation; grant support and personal fees from Receptos, Amgen, Prometheus Laboratories, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Atlantic Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Pfizer, and Nutrition Science Partners; and personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene Cellular Therapeutics, Santarus, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Catabasis Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Warner Chilcott, Gilead Sciences, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Tillotts Pharma, Am Pharma BV, Dr. August Wolff, Avaxia Biologics, Zyngenia, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Index Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, UCB Pharma, Orexigen, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Baxter Healthcare, Ferring Research Institute, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Mesoblast Inc., Shire, Ardelyx Inc., Actavis, Seattle Genetics, MedImmune (AstraZeneca), Actogenix NV, Lipid Therapeutics Gmbh, Eisai, Qu Biologics, Toray Industries Inc., Teva Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Chiasma, TiGenix, Adherion Therapeutics, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Ambrx Inc., Akros Pharma, Vascular Biogenics, Theradiag, Forward Pharma, Regeneron, Galapagos, Seres Health, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Theravance, Palatin, Biogen, and the University of Western Ontario (owner of Robarts Clinical Trials).

Abbreviations:

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- 5ASA

5-aminosalycilate

- EIMs

Extra-Intestinal Manifestations

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein CN, Ng SC, Lakatos PL, et al. A review of mortality and surgery in ulcerative colitis: milestones of the seriousness of the disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2001–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan GG, Seow CH, Ghosh S, et al. Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of adult Crohn’s disease in population-based cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fumery M, Duricova D, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Review article: the natural history of paediatric-onset ulcerative colitis in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Booth CM, Tannock IF. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:551–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szklo M et al. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, et al. Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vester-Andersen MK, Prosberg MV, Jess T et al. Disease course and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based, 7-year follow-up study in the era of immunomodulating therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:705–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, et al. Prospective population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease in the biologics era: Disease course and predictors of severity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuel S, Ingle SB, Dhillon S, et al. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for hospitalization and surgery in a population-based cohort of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1858–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vegh Z, Kurti Z, Gonczi L, et al. Association of extraintestinal manifestations and anaemia with disease outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng SC, Zeng Z, Niewiadomski O, et al. Early Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Population-Based Inception Cohort Study From 8 Countries in Asia and Australia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. C-reactive protein: a predictive factor and marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a prospective population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1518–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, et al. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:371–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Söderlund S, Brandt L, Lapidus A et al. Decreasing time-trends of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1561–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witte J, Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones JE, et al. Disease outcome in inflammatory bowel disease: mortality, morbidity and therapeutic management of a 796-person inception cohort in the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vegh Z, Burisch J, Pedersen N, et al. Incidence and initial disease course of inflammatory bowel diseases in 2011 in Europe and Australia: results of the 2011 ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1506–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sjöberg D, Holmström T, Larsson M, et al. Incidence and clinical course of Crohn’s disease during the first year - results from the IBD Cohort of the Uppsala Region (ICURE) of Sweden 2005–2009. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewénius J, Adnerhill I, Ekelund GR, et al. Risk of relapse in new cases of ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobsen C, Bartek J Jr, Wewer V, et al. Differences in phenotype and disease course in adult and paediatric inflammatory bowel disease--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Høie O, Aamodt G, Vermeire S, et al. Serological markers are associated with disease course in ulcerative colitis. A study in an unselected population-based cohort followed for 10 years. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vind I, Riis L, Jespersgaard C, et al. Genetic and environmental factors as predictors of disease severity and extent at time of diagnosis in an inception cohort of inflammatory bowel disease, Copenhagen County and City 2003–2005. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golovics PA, Lakatos L, Mandel MD, et al. Prevalence and predictors of hospitalization in Crohn’s disease in a prospective population-based inception cohort from 2000–2012. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leijonmarck CE, Löfberg R, Ost A, Hellers G. Long-term Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:195–200.results of ileorectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis in Stockholm County.

- 29.Katsanos KH1, Vermeire S, Christodoulou DK, et al. Dysplasia and cancer in inflammatory bowel disease 10 years after diagnosis: results of a population-based European collaborative follow-up study. Digestion. 2007;75:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jess T, Horváth-Puhó E, Fallingborg J, et al. Cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease according to patient phenotype and treatment: a Danish population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovde Ø, Småstuen MC, Høivik ML, et al. Mortality and Causes of Death in Ulcerative Colitis: Results from 20 Years of Follow-up in the IBSEN Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewénius Adnerhill I, Ekelund GR, et al. Operations in unselected patients with ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis. A long-term follow-up study. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakatos L, Kiss LS, David G, et al. Incidence, disease phenotype at diagnosis, and early disease course in inflammatory bowel diseases in Western Hungary, 2002–2006.Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeuring SF, Bours PH, Zeegers MP, et al. Disease Outcome of Ulcerative Colitis in an Era of Changing Treatment Strategies: Results from the Dutch Population-Based IBDSL Cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:837–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH; IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoie O, Wolters FL, Riis L et al. Low colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis in an unselected European cohort followed for 10 years. Gastroenterology. 2007. February;132(2):507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh S, Al-Darmaki A, Frolkis AD et al. Postoperative Mortality Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Population-Based Studies. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winther KV, Jess T, Langholz E, Munkholm P, Binder V. Long-term risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study from Copenhagen County. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1088–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakatos L, Mester G, Erdelyi Z, et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in a Hungarian cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis: results of a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Velayos FS, et al. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from olmsted county, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manninen P, Karvonen AL, Huhtala H, et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Finland: a follow-up of 20 years. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palli D, Trallori G, Saieva C, et al. General and cancer specific mortality of a population based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the Florence Study. Gut. 1998;42:175–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlén P, Löfberg R, Broström O, Leijonmarck CE, Hellers G, Persson PG. Increased risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1047–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadav S, Singh S, Harmsen WS, et al. Effect of Medications on Risk of Cancer in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Population-Based Cohort Study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pedersen N, Duricova D, Elkjaer M, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Jess T. Risk of extra-intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1480–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romberg-Camps MJ, Bol Y, Dagnelie PC, et al. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a population-based study in the Netherlands: the IBD-South Limburg cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burisch J, Weimers P, Pedersen N, et al. Health-related quality of life improves during one year of medical and surgical treatment in a European population-based inception cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease--an ECCO-EpiCom study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1030–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Schulz T et al. Course of disease, drug treatment and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease 5 years after initial diagnosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1037–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Israeli E, Graff LA, Clara I, et al. Low prevalence of disability among patients with inflammatory bowel diseases a decade after diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1330–7.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Høivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, Henriksen M, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T. Work disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients 10 years after disease onset: results from the IBSEN Study. Gut. 2013;62:368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Höie O, Schouten LJ, Wolters FL, et al. Ulcerative colitis: no rise in mortality in a European-wide population based cohort 10 years after diagnosis. Gut. 2007;56:497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hovde Ø, Småstuen MC, Høivik ML, et al. Mortality and Causes of Death in Ulcerative Colitis: Results from 20 Years of Follow-up in the IBSEN Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romberg-Camps M1, Kuiper E, Schouten L, et al. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease in the Netherlands 1991–2002: results of a population-based study: the IBD South-Limburg cohort. . Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masala G, Bagnoli S, Ceroti M, et al. Divergent patterns of total and cancer mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients: the Florence IBD study 1978–2001. Gut. 2004;53:1309–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manninen P, Karvonen AL, Huhtala H, et al. Mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. A population-based study in Finland. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:524–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jess T, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2004. Gut. 2006;55:1248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Persson PG, Bernell O, Leijonmarck CE, Farahmand BY, Hellers G, Ahlbom A. Survival and Cause-Specific Mortality in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isene R, Bernklev T, Høie O, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from a prospective, population-based European inception cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palm Ø, Moum B, Jahnsen J, Gran JT. The prevalence and incidence of peripheral arthritis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a prospective population-based study (the IBSEN study). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:1256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shivashankar R, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. Incidence of Spondyloarthropathy in patients with ulcerative colitis: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:1153–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yadav S, Singh S, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, et al. Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Høivik ML, Reinisch W, Cvancarova M, Moum B. Anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based 10-year follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sjöberg D, Holmström T, Larsson M, Nielsen AL, Holmquist L, Rönnblom A. Anemia in a population-based IBD cohort (ICURE): still high prevalence after 1 year, especially among pediatric patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ott C, Liebold A, Takses A, Strauch UG, Obermeier F. High prevalence but insufficient treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a population-based cohort. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:595970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loftus EV Jr, Achenbach SJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Oberg AL, Melton LJ 3rd. Risk of fracture in ulcerative colitis: a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leslie WD, Miller N, Rogala L, Bernstein CN. Body mass and composition affect bone density in recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease: the Manitoba IBD Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Isene R, Bernklev T, Høie O, et al. Thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a prospective, population-based European inception cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:820–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vegh Z, Golovics PA, Lovasz BD, et al. Low incidence of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel diseases: prevalence and predictors from a population-based inception cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:306–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stewénius J, Adnerhill I, Anderson H, et al. Incidence of colorectal cancer and all cause mortality in non-selected patients with ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis in Malmö, Sweden. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lakatos PL, Lovasz BD, David G, et al. The risk of lymphoma and immunomodulators in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: results from a population-based cohort in Eastern Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.JF, Narula N, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Management Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:351–361.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Cumulative probabilities of colectomy in population-based studies.