Abstract

Background:

Infants with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treated with high-dose methotrexate (MTX) may have reduced MTX clearance (CL) due to renal immaturity, which may predispose them to toxicity. The objective of this study was to develop a population pharmacokinetic (PK) model of MTX in infants with ALL.

Methods:

A total of 672 MTX plasma concentrations were obtained from 71 infants enrolled in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Clinical Trial P9407. Infants received MTX 4 g/m2 intravenously for four cycles during weeks 4–12 of intensification. A population PK analysis was performed using NONMEM® version 7.4. The final model was evaluated using a non-parametric bootstrap, a visual predictive check, and simulations were performed to evaluate MTX dosage and the utility of a bedside algorithm for dose individualization.

Results:

MTX was best characterized by a two-compartment model with allometric scaling. Weight was the only covariate included in the final model. The coefficient of variation for interoccasion variability (IOV) on CL was relatively high at 25.4%, compared to the interindividual variability for CL and central volume of distribution, 10.7% and 13.2%, respectively. Simulations identified that 21.1% of simulated infants benefitted from bedside dose adjustment, and adjustment of MTX doses during infusions can avoid supratherapeutic concentrations.

Conclusion:

Infants treated with high-dose MTX demonstrated a relatively high degree of IOV in MTX CL. The magnitude of IOV in the CL of MTX suggests that use of a bedside algorithm may avoid supratherapeutic MTX concentrations resulting from high IOV in MTX CL.

Keywords: methotrexate, infants, pediatrics, pharmacokinetics, population modeling, NONMEM, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, cancer, interoccasion variability

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common form of pediatric cancer, representing 25% of all cancers diagnosed in children under 15 years of age [1,2]. Over the past several decades there have been significant improvements in the prognosis of pediatric ALL, and 5-year overall survival for contemporary treatment protocols has approached 90% [3]. Despite this improvement, the outcomes of infants diagnosed at less than 1 year of age have been consistently worse [4]. The explanation for this lack of improvement in the clinical outcomes of infant ALL has not been fully elucidated. However, there are features of infant ALL thought to be responsible for its poor prognosis; these include both the greater frequency of high-risk genetic mutations as well as higher tumor burden at presentation [5–7]. In addition to these factors, physiological differences between infants and older children may lead to alterations in drug disposition and pharmacokinetics (PK) of chemotherapy that may affect infant outcomes. This has led to the development of infant specific protocols designed to increase the intensity of therapy in these subjects [3,4,7].

Methotrexate (MTX) is an anti-neoplastic agent used commonly in a variety of childhood malignancies, and is a crucial component to ALL treatment protocols [8,9]. MTX is a folate analogue that competitively inhibits the activity of dihydrofolate dehydrogenase (DHFR), causing depletion of purines and thymidylate which halts DNA synthesis causing cell death [10,11]. This effect is amplified in rapidly dividing cells, leading to MTX’s S-phase specific cytotoxicity [8]. Due to the high expression of DHFR in ALL cells, high-dose MTX is one therapeutic strategy utilized to saturate DHFR and maximize cytotoxicity [12,13]. However, high-dose MTX requires both therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and significant supportive care to avoid excessive exposure to MTX which has been shown to cause nephrotoxicity, myelotoxicity, mucositis, neurological complications, and other adverse effects [14,15].

Based on the physiologic differences between infants and older children, the PK of MTX in infants may be altered due to several factors. Firstly, MTX is primarily eliminated by renal excretion, as adult studies have shown that approximately 70–90% of each dose is excreted unchanged in urine [15,16]. Infants are known to have both delayed and variable maturation of renal tubule function, glomerular filtration rate, and renal blood flow [17–20]. Therefore, elimination of MTX in younger infants may be significantly delayed compared to older children, which could increase toxicity. Additionally, MTX is known to have delayed elimination in patients with extracellular fluid accumulations [14]. This may affect drug disposition in infants, who are known to undergo significant changes in total body water content from approximately 75% during the neonatal period to 55% in adulthood [21,22].

Despite these concerns, to date there are limited published PK analyses describing the disposition of MTX in this vulnerable patient population. Moreover, few studies have included infants <6 months of age when these physiological changes are most relevant, and none have used population PK to characterize the disposition of methotrexate in this patient population [21,23,24]. The use of population PK offers several unique advantages over conventional PK analyses, most notably the ability to quantify the effects of patient covariates on drug exposure using sparse PK sampling [25–27]. A non-compartmental analysis with a portion of the data used for the current study was previously published [28], but a population PK analysis has not been previously performed. The objectives of this study were to develop a population PK model of MTX in infants with ALL, to characterize the impact of interoccasion variability (IOV) on this model, and to use simulations to evaluate the impact of various doses on MTX exposure.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient Population

MTX concentrations were obtained from infants enrolled in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Clinical Trial P9407, a portion of which were enrolled in a PK sub-study. The details of the study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, treatment protocol, and PK sampling were described previously [28]. Briefly, this study included subjects with newly diagnosed ALL, <366 days postnatal age (PNA), and >36 weeks gestational age at birth with congenital ALL. Exact dates of infusions were not available for all subjects, therefore age at infusion was imputed based on expected age using the study protocol. This study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration [28].

2.2. Drug Administration and Supportive Care

All patients enrolled received the same chemotherapy regimen, an intensified induction including high-dose MTX, and supportive care as described previously [28]. Subjects received their first cycle of MTX at week 4 of induction/intensification. High-dose MTX was administered as a 24 hour (h) intravenous (IV) infusion, with a 200 mg/m2 loading dose over 20 min, followed by a 3.8 g/m2 dose over the remainder of the 24 h. This dosing regimen was repeated at week 5 of induction intensification and in consolidation at weeks 11 and 12 of therapy. Standard supportive care for high-dose MTX was provided, including hydration with alkalinized IV fluids and leucovorin rescue. MTX plasma concentrations are reported here as micromoles/L (μM) [28].

2.3. Pharmacokinetic Sampling

Beginning with the first cycle of MTX given at week 4, standard MTX monitoring was performed for all subjects at the end of drug infusion and 24 h later. Subsequent concentrations were monitored every 12–24 h until the MTX concentration was <0.18 μM. This standard monitoring was also performed during weeks 5, 11, and 12 of therapy. In addition to this, subjects enrolled in the PK sub-study had intensive MTX PK sampling at 1, 6, 12, and 23 h after the start of MTX infusions [28].

2.4. Bioanalytical Assay

Samples obtained as part of standard MTX monitoring were analyzed in the clinical laboratories of the treating hospitals. The most common assays used for quantification of MTX included fluorescence polarization immunoassay and the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay [29,30]. For the PK sub-study, samples were analyzed at the central study laboratory at Texas Children’s Hospital using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method [31]. For all MTX samples included in this analysis, a conservative lower limit of quantification (LLQ) of 0.05 μM was assumed, which is used commonly in clinical practice [14,28].

2.5. Population Pharmacokinetic Model Development

Population PK analyses were performed using NONMEM® version 7.4 (ICON Development Solutions; Ellicott City, MD, USA) using MTX concentration versus time data for all infants with MTX concentration data. The effect of log-transforming MTX concentration data was investigated. The first-order conditional estimation (FOCE) method with interaction was applied for all model runs. All data manipulation and visualization of diagnostic plots were executed using R (version 3.0.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and RStudio (version 0.99, RStudio, Boston, MA, USA), with the packages lattice, latticeExtra, and ggplot2 [32–34]. Model development was guided by run minimization, successful covariance steps, objective function value (OFV) changes for each nested model, plausibility and precision of parameter estimates, evaluation of eta and epsilon shrinkage, reduction in residual variability, and manual inspection of diagnostic plots including visual prediction checks (VPCs).

Both one and two-compartment structural models were evaluated. The base model assumed a standard allometric scale based on total body weight (WT). A single exponential value of 0.75 was assumed for clearance (CL) and intercompartmental clearance (Q). A single exponential value of 1.0 was assumed for central volume of distribution (Vc) and peripheral volume of distribution (Vp) [17,35]. Estimation of these exponents was also investigated. Standard PK equations were applied for a two-compartment model using the ADVAN3 TRANS4 subroutines in NONMEM®. Inter-individual variability (IIV) was assessed for all PK model parameters using an exponential relationship as shown below for a two-compartment model (Eq. 1–4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where CLi, Vc,i, Vp,i, and Qi are the individual values of CL, Vc, Vp and Q, respectively; θCL,std, , , and θQ,std are the respective parameter values for a subject with a body weight of 70 kg; WTi is the individual subject weight; ηi,CL, , and ηi,Q are random effect parameters assumed to be symmetrically distributed with a mean equal to zero and variance estimated as ωCL2, , and ωQ2 which describe each individual’s variation from the population estimate. Covariance between these variability estimates was evaluated for each parameter.

In addition to the IIV, IOV was also characterized for each PK parameter as follows (Eq. 5)

| (5) |

where i indicates the ith individual, k indicates the kth occasion, the typical value is the mean value of the parameter in the population, ηi is the random effect accounting for IIV, and κi is the random effect account for IOV [36,37]. Each treatment cycle was treated as a different occasion, and IOV was assumed to be the same across occasions. Both additive, exponential, and combined residual error models were tested.

Covariates available for analysis including weight, age, body surface area (BSA), and sex. Covariates were evaluated for the model in a stepwise fashion based on changes in the OFV first by forward inclusion (P<0.05 and ΔOFV > 3.8) followed by backward elimination (P<0.001 and ΔOFV of >10.8). Both continuous and categorical covariates were tested using the power model normalized as follows (Eq. 6–7):

| (6) |

| (7) |

where Pi,j indicates the jth parameter estimate for the ith individual, θpop,std indicates the population parameter values for a subject with a body weight of 70 kg, covi indicates the individual covariate value for the ith individual, covm indicates the median population covariate value, θcov is the parameter indicating the covariate effect, and CATEGORICAL is a categorical variable which can take on values of zero or one.

2.6. Model Evaluation

The precision of the final population PK model parameter estimates were evaluated using non-parametric bootstraps with 1000 replicates to generate 95% confidence intervals of each parameter using the percentile method [38]. VPCs were run on key models to assess model performance and robustness. VPCs were performed with Perl-speaks-NONMEM (version 3.6.2) and visualized in R using xpose4 [39,40].

2.7. Model Simulations

For all simulations, a virtual population of 1000 infants was created assuming all subjects were of full gestational age, and a similar weight distribution as our study population. Monte Carlo simulations were performed to assess the frequency of subtherapeutic and supratherapeutic MTX concentrations with doses of 2, 4, 6, and 8 g/m2 of MTX given IV over 24 h. For each dose, MTX concentrations were simulated at 2, 6, 8, 24, 42, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, 168, 216, and 240 h. Simulations were repeated to generate four cycles of simulated MTX concentrations for each subject. Target methotrexate concentrations were defined based on previous literature suggesting that methotrexate concentrations < 16 μM at 24 h are associated with relapse and are subtherapeutic, and methotrexate concentrations > 100 μM at 24 h, > 1.0 μM at 48 h, and > 0.1 μM at 72 h are associated with increased toxicity and are supratherapeutic [41,42].

The R package mlxR was used to simulate a “bedside algorithm” for individualizing high-dose MTX exposure similar to those proposed previously [43,44]. This algorithm adjusts the rate of MTX infusion according to MTX concentrations obtained at 2 and 6 h after start of a 24 h IV infusion of 4 g/m2 of MTX. Simulations maintained an infusion length of 24 h which is known to be essential to MTX’s antitumor activity. At 2 h, the infusion rate was decreased by 50% in subjects with MTX concentrations >100 μM. At 6 h, the infusion rate was decreased by 25% for subjects with MTX concentrations between 75 – 100 μM, and the infusion rate was decreased by 50% in subjects with MTX concentrations >100 μM. The percent of subjects requiring dose adjustment was calculated, and the median 24 h concentration was compared between subjects that did or did not require dose adjustments.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient Data

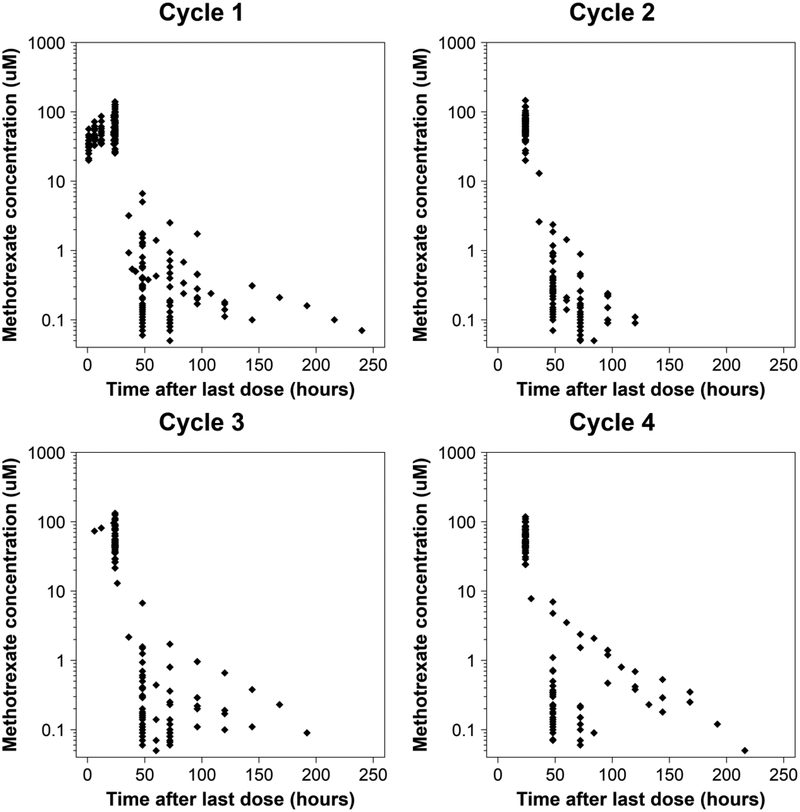

A total of 690 MTX concentrations were available from 71 subjects who underwent 229 cycles of high-dose MTX treatment for ALL. There were 2.6% (18/690) MTX concentrations below LLQ of 0.05 μM, all of which were excluded [45]. The PK profile of all 71 subjects stratified by cycle is shown in Figure 1. Intensive MTX PK sampling was performed in 24.0% (17/71) of subjects enrolled, and 92.0% (65/71) of subjects had PK data for more than one occasion. Of subjects who had intensive PK monitoring, 94.1% (16/17) of these intensive collections occurred during cycle 1. There were no differences in the baseline demographics between subjects in the PK sub-study and the routine clinical care group (Table 1). For the majority of MTX cycles, subjects received MTX doses close to 4 g/m2. However, for 14.4% (33/229) of cycles patients received doses <3.5 g/m2 (median 2.99 gm/m2, range 2.0 – 3.48 gm/m2), and for 1.3% (3/229) of cycles subjects received doses >4.5 g/m2 (median 5.63 gm/m2, range 5.34–5.63). The reason for dose modification in these subjects is unknown to us.

Fig. 1.

Methotrexate plasma concentrations from 229 cycles in 71 infants subset by treatment cycle. The x-axis represents time after the start of the 24 hour methotrexate infusion. The y-axis represents plasma methotrexate on a log scale.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of infants included in the study

| Study | aPharmacokinetic sub-study group (n=17) | bRoutine clinical care group (n=54) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Median | Range | Median | Range |

| cPost-natal age (months) | 8.5 | 2.9 – 12.9 | 7.0 | 1.0 – 12.9 |

| cTotal body weight (kg) | 8.6 | 4.5 – 11.9 | 7.6 | 3.0 – 12.1 |

| cHeight (cm) | 69 | 51 – 78 | 66.5 | 49.7 – 79.0 |

| cBody surface area (m2) | 0.40 | 0.24 – 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.20 – 0.48 |

| Methotrexate dose (g) | 1.5 | 0.62 – 1.96 | 1.4 | 0.60 – 2.2 |

| Methotrexate dose (g/m2) | 4.0 | 2.0 – 4.5 | 4.0 | 2.0 – 5.6 |

| Methotrexate C24h (μM) | 54.7 | 24.2 – 146.6 | 61.5 | 24.0 −140.0 |

| Methotrexate C48h (μM) | 0.2 | 0.07 – 7.0 | 0.20 | 0.06 – 6.7 |

| Methotrexate C72h (μM) | 0.17 | 0.07 – 2.4 | 0.11 | 0.05 – 2.5 |

8 males; 9 females

24 males; 30 females

Reported at first treatment course

Methotrexate dose = total dose given as a 24-hour infusion, Cxh = plasma concentration of methotrexate at x hours

3.2. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis

MTX plasma concentrations were best characterized by a two-compartment model with linear elimination. Data was log-transformed as model minimization was not achievable using raw concentrations, likely due to the wide range of concentrations. After allometrically scaled total body weight was incorporated into CL, Vc, Vp, and Q terms, no other covariates were found to be significant. Visual inspection of the eta plots revealed a weak association between age and CL, but incorporating this as a covariate reduced the OFV by <3.8. Visual inspection of the empirical Bayesian estimates (EBEs) for CL did not reveal a correlation with age or treatment cycle (Electronic Supplemental Materials). Estimation of the allometric scaling factors for CL and volume of distribution terms did not improve the OFV, increased the shrinkage of IIV estimates, and resulted in estimates similar to fixed exponents, 0.80 and 0.98 respectively, and therefore these were fixed. The final model included estimation of the IIV on both CL and Vc, as well as IOV on CL. A correlation between the IIV of CL and Vc was noted in diagnostic plots, however this was not included in the final model as estimation of this term resulted in a relatively small correlation coefficient (0.383), and did not allow for a successful covariance step. Estimation of IIV and IOV on other model parameters was not included in the final model due to inflation of the eta shrinkage values to >60% for IIV estimates. The final model included a single proportional residual error model for all MTX concentrations.

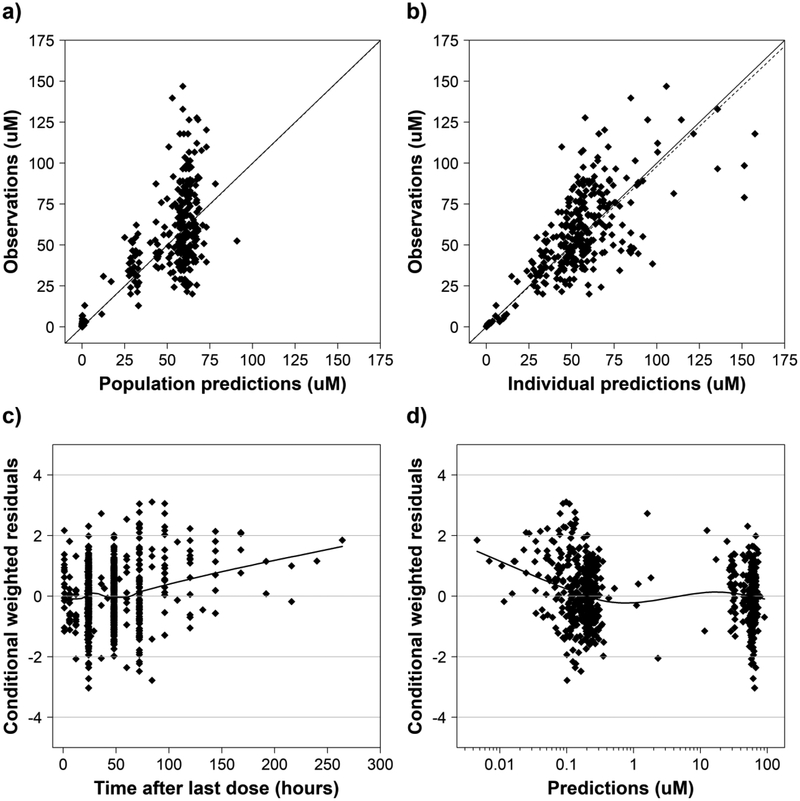

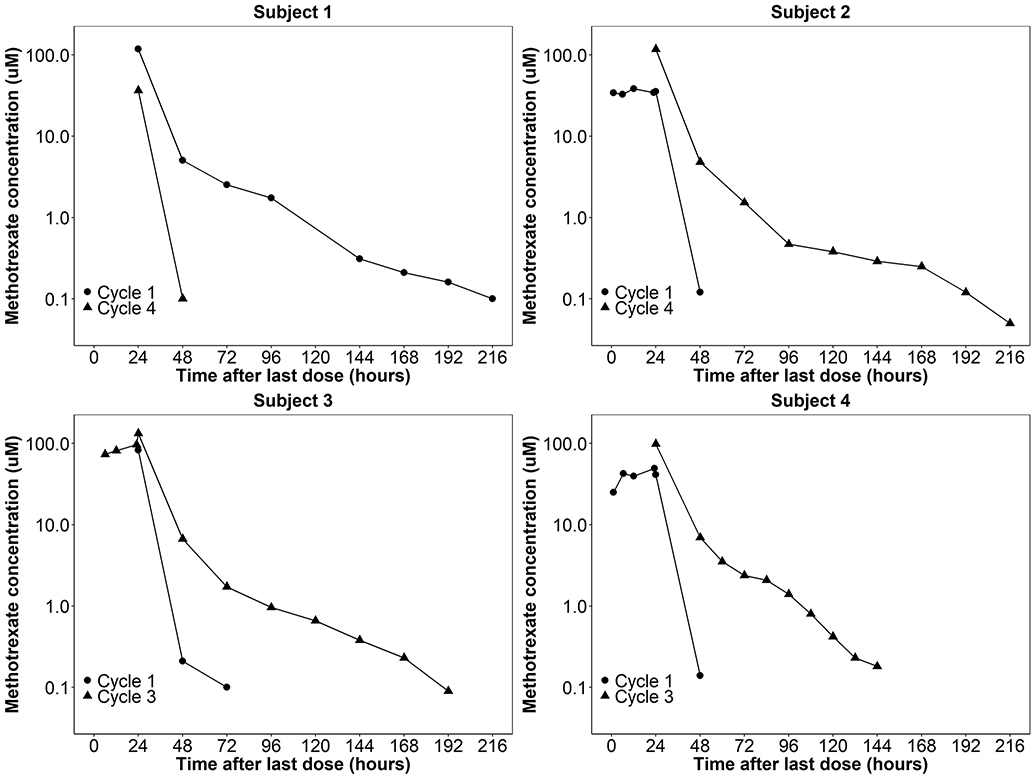

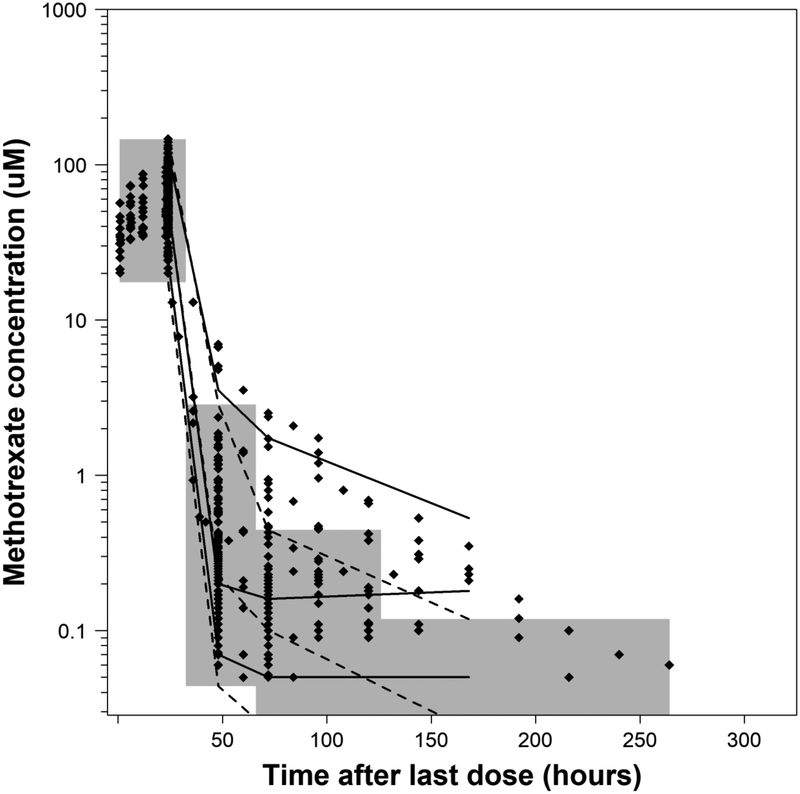

The diagnostic plots for the final population PK model are shown in Figure 2. These plots demonstrate some misspecification in the population predictions, which is improved with the incorporation of IIV and IOV in the individual predictions. Additionally, while panel C appears to show misspecification occurring at concentrations observed at >200 h after dosing, this is likely due to the small number of MTX observations. The final model PK parameters, standard errors, and results of the bootstrap analysis are shown in Table 2. Overall, there was a relatively high degree of IOV on CL (25.4%) compared to both the IIV on CL (10.7%) and IIV on Vc (13.2%). All parameter estimates fell within 10% of the median bootstrap estimates suggesting reasonable precision of parameter estimates. Four example subjects who demonstrated a high degree of IOV in their methotrexate CL are shown in Figure 3. The results of the VPC are shown in Figure 4, and demonstrate that the model captures the observed variability well. Notably, 11.9% (80/672) of the observations fell outside of the 90% prediction interval, suggesting a slight underestimation of the random effects. Few MTX observed concentrations fell below the 5% prediction interval, suggesting the final model prediction for CL may be slightly overestimated. These results were similar when a VPC was performed focusing solely on the first 72 h after infusion (Electronic Supplemental Materials).

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic plots of the final population pharmacokinetic model. a) Population predicted concentrations versus observations, b) individual predictions versus observations, c) time after last dose versus conditional weighted residuals, and d) population predicted concentrations versus conditional weighted residuals. For a) and b), the dashed line represents the line of unity and the solid line represents a linear regression. For c) and d), the black line represents the LOESS curve, and the grey lines represent conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) values of −4, −2, 0, 2, and 4.

Table 2.

Final population pharmacokinetics model parameter estimates and bootstrap results

| Final Model | aBootstrap Analysis (N=1000) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimateb(RSE%) | 5th Percentile | Median | 95th Percentile |

| cFixed Effects | ||||

| (L/h/70 kg) | 11.0 (3.1) | 10.4 | 11.0 | 11.6 |

| (L/70 kg) | 63.4 (5.1) | 57.2 | 62.9 | 69.0 |

| (L/70 kg) | 13.6 (8.5) | 10.6 | 13.3 | 15.6 |

| (L/h/70 kg) | 0.13 (7.6) | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| dInter-individual variability (IIV) | ||||

| (IIV as CV%) | 10.7 (49.7) | 5.23 | 10.7 | 14.7 |

| (IIV as CV%) | 13.2 (56.2) | 5.74 | 12.7 | 18.7 |

| cInter-occasion variability (IOV) | ||||

| (IOV as CV%) | 25.4 (21.1) | 20.9 | 25.3 | 29.8 |

| eResidual variability (RV) | ||||

| Proportional Error (%) | 37.5 (7.52) | 34.9 | 37.2 | 39.6 |

A total of 951 runs (95.1%) successfully minimized and 1000 (100%) runs completed the covariance step

RSE is the relative standard error defined as the standard error of the estimate divided by the final parameter estimate multiplied by 100

Theory based allometry was applied such that model parameters are standardized to a 70 kg adult assuming an exponent of 0.75 for clearance terms and 1.0 for volume of distribution terms; is the population clearance standardized to a 70 kg adult, is the population central volume of distribution standardized to a 70 kg adult, is the population peripheral volume of distribution standardized to a 70 kg adult, is the population intercompartmental clearance standardized to a 70 kg adult

Model estimates reported in CV%; is the variance of the IIV for clearance, is the variance of the IIV for volume, is the variance of the IOV on clearance.

Proportional residual error coded as additive on logarithmic scale

Fig 3.

Four infants demonstrating high interoccasion variability in their clearance of methotrexate. Each subject received the same weight based dose of high dose methotrexate of 4 g/m2. The x-axis represents time after the start of the 24 hour methotrexate infusion. The y-axis represents plasma methotrexate concentrations on log scale.

Fig. 4.

Final model visual predictive check. A total of 80 points (11.9%) fell outside the 90% prediction interval. Dotted and solid lines represent the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the simulated data and observed data, respectively. Gray shaded areas represent the 90% prediction interval. The x-axis represents time after the start of the 24 hour methotrexate infusion. The y-axis represents plasma methotrexate concentrations on log scale.

3.4. Model Simulations

The results of the dose ranging simulation are shown in Table 3. None of the dosing regimens evaluated resulted in simulated 24 h MTX concentrations <16 μM. Additionally, compared to the study dose of 4 g/m2, escalating doses of 6 g/m2 and 8 g/m2 resulted in a substantial increase in the percentage of simulated supratherapeutic MTX concentrations. The percent of subjects with supratherapeutic MTX concentrations at 72 h (>0.1 μM) was high for all simulated doses, similar to the exposures in our subjects who received 4 g/m2. This suggests further research may be needed to define supratherapeutic concentrations at 72 h in this patient population.

Table 3.

Simulation results of 1000 virtual patients treated with four cycles of high dose methotrexate

| Clinical Endpoint | Dose of Methotrexate Simulated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 g/m2 | 4 g/m2 | 6 g/m2 | 8 g/m2 | |

| aMTX C24h (μM) | 33.5 (27.9 – 40.0) | 67.4 (55.7 – 79.8) | 100.5 (83.7 – 119) | 134.3 (111 – 159) |

| aMTX C48h (μM) | 0.125 (0.0735 – 0.235) | 0.250 (0.147 – 0.470) | 0.375 (0.221 – 0.705) | 0.501 (0.295 – 0.940) |

| aMTX C72h (μM) | 0.0672 (0.0592 – 0.0983) | 0.134 (0.0907 – 0.196) | 0.202 (0.135 – 0.292) | 0.267 (0.181 – 0.392) |

| bSubtherapeutic at 24 h | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| cSupratherapeutic at 24 h | 0.3 % | 6.28% | 51.1% | 85.5% |

| cSupratherapeutic at 48 h | 3.05% | 9.43% | 16.4% | 23.3% |

| cSupratherapetuic at 72 h | 24.0% | 69.3% | 89.0% | 95.6% |

| dTime to MTX <0.05 μM | 42 (42 – 72) | 42 (42 – 48) | 42 (42 – 96) | 42 (42 – 120) |

MTX Cx is simulated methotrexate concentration at time x reported as median (25th – 75th percentile)

The percent of subjects subtherapeutic at 24 hours (<16 μM)

The percent of subjects supratherapeutic at 24 hours (>100 μM), 48 hours (>1 μM) and 72 hours (>0.1 μM)

Reported in hours as median (minimum - maximum)

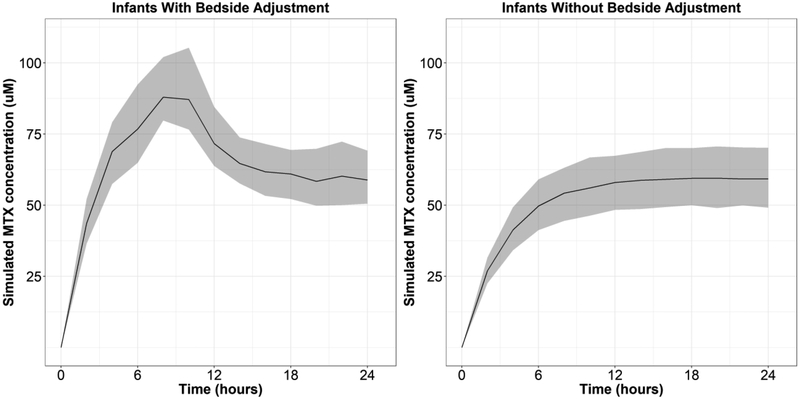

Simulation of a bedside algorithm showed that without dosage adjustment, 21.1% (211/1000) of infants receiving a single cycle of 4 g/m2 would be expected to achieve supratherapeutic MTX concentrations, similar to published reports [43,46]. A total of 214 dose adjustments were made, of which 1.87% (4/214) were a 50% decrease in infusion rate at 2 h due to a simulated methotrexate concentration >100 μM, 29.0% (62/214) were a 50% decrease in infusion rate at 6 h due to a simulated methotrexate concentration >100 μM, and 69.2% (148/214) were a 25% decrease in infusion rate at 6 h due to a simulated methotrexate concentration between 75 and 100 μM. All four simulated infants who required dose adjustment at 2 hours also required adjustment at 6 hours, and therefore 21.1% (211/1000) of simulated infants had their dose modified by the algorithm. As shown in Figure 5, dose adjustment using this bedside algorithm resulted in similar median (25th percentile – 75th percentile) 24 h MTX concentrations between subjects requiring dose adjustment and those that did not, 58.8 μM (50.5 – 69.2) and 59.1 μM (49.5 – 69.7), respectively. These results suggest that the application of a simple algorithm to adjust MTX infusion rate may make targeted MTX exposure more feasible, and can overcome the challenge of IOV in MTX CL between cycles.

Fig 5.

Simulated methotrexate (MTX) exposures in 1000 virtual infants using a bedside adjustment with the R package mlxR. This algorithm adjusts the rate of MTX infusion according to MTX concentrations obtained at 2 and 6 h after the start of a single 24 h IV infusion of 4 g/m2 of MTX. At 2 h, the infusion rate was decreased by 50% in subjects with MTX concentrations >100 μM. At 6 h, the infusion rate was decreased by 25% for subjects with MTX concentrations between 75 – 100 μM, and the infusion rate was decreased by 50% in subjects with MTX concentrations >100 μM. The x-axis represents time after the start of infusion. The y-axis shows simulated MTX concentrations. The dark black line denotes the median MTX concentration, and the gray shaded region shows the 25th – 75th percentiles of simulated MTX concentrations. The left panel shows simulated MTX concentrations in subjects requiring bedside adjustment (211/1000), and the right panel shows simulated MTX concentrations in subject without dosage adjustment (789/1000).

4. DISCUSSION

TDM of high-dose MTX remains an essential practice for identifying subjects at risk for MTX toxicity and informing supportive care measures [14,47]. Previous research has shown that individualization of MTX exposure using TDM can reduce the incidence of MTX toxicity and improve patient outcomes [41,46]. Individualization of MTX exposure is challenging due to the known within subject and between subject variability of MTX CL, which may be better characterized using population PK modeling [24,48,49]. Therefore, the objective of our study was to develop a population PK model of MTX in infants with ALL, and to quantify the effects of IOV between cycles on this PK model.

To date, this is the largest population PK model of high-dose MTX in infant ALL, and the first to include infants as young as 2 months PNA. Our PK dataset consisted of MTX plasma concentrations collected as part of routine care combined with MTX plasma concentrations from infants enrolled in a PK sub-study [28]. The PK sub-study data significantly improved model fitting by increasing the total number of MTX concentrations, and by providing MTX concentration data drawn during the infusion which are informative for MTX parameter estimation. Additionally, our PK dataset contained multiple cycles of MTX concentrations, which allowed us to quantify the within subject variability in PK parameters across cycles as IOV.

A two-compartment model best characterized the PK of MTX in the 71 infants in our study, which is consistent with previous reports of high-dose MTX in both children and adults [46,48,50–57]. Our model applied theory based allometry to scale CL and volume of distribution parameters to a standard weight of 70 kg [17,58]. The resulting final model CL and Vc estimates scaled to a 70 kg adult are similar to published reports in adults [52,59,60]. Additionally, a retrospective case-control study comparing the PK of high-dose MTX in pediatric ALL subjects applied an identical methodology for allometric scaling of CL and Vd terms [51]. The final parameter estimates scaled to a 70 kg adult from this previously published model were a CL of 13 L/h/70kg and a Vc of 46 L/70kg, which compare favorably to our estimates of 11.0 L/h/70 kg and 63.4 L/70kg, respectively. Our weight-normalized final model estimate of CL was 0.273 L/h/kg, which falls within the range of reported adult and pediatric literature values of 0.117 – 0.374 L/h/kg. Similar to our estimate for CL, our final model estimate of Vc of 0.910 L/kg falls within the range of reported values of 0.356 – 1.27 L/kg in adults and pediatrics [30,48,50,55–57,61].

We did not identify age as a covariate impacting CL, which has been described previously [46,48,62–64]. However, the impact of age on MTX CL has been reported inconsistently, as there are multiple published PK analyses which have found no impact of age on CL of MTX in pediatric subjects [50,54,57]. The effect of renal maturation, reflected in modeling PNA as a covariate on methotrexate CL, would be expected to be highest in both premature infants as well as full-term infants <6 months of age [17–20]. Therefore it is possible that we were unable to identify PNA as a significant covariate on MTX CL because our data only included 28.4% (65/229) of cycles with infants <6 months of age, and premature infants were excluded from this study.

Our study demonstrated a similar magnitude of IOV in the CL of MTX compared to previous studies performed in children [48,51,65]. This variation in the CL of MTX across cycles may be explained by changes in disease progression, drug-drug interactions, or unmeasured covariates which vary across cycles. The magnitude of IOV in the CL of MTX suggests that Bayesian adaptive dosing algorithms may be optimized by obtaining MTX concentrations during the current cycle infusion, rather than concentrations measured from previous cycles.

Simulations revealed that dosing regimens of 2–8 g/m2 provide sufficient MTX exposure based on the 24 h MTX target of 16 μM [41]. However, increasing doses of high-dose MTX above 4 g/m2 may result in untoward renal toxicity, as >15% of all simulated infants would have experienced supratherapeutic MTX concentrations. Application of the final population PK model using a bedside dosing algorithm revealed the potential clinical impact of our protocol, as our simulated individualization strategy reduced supratherapeutic MTX concentrations in 21.1% of simulated subjects. Future prospective studies individualizing MTX exposure using a similar approach are needed to evaluate the impact of such a bedside algorithm on patient outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study data included limited covariates, and notably we did not have markers of renal function. Despite this, all infants were screened for adequate organ function prior to each MTX treatment cycle, including a creatinine CL >70 mL/min/1.73 m2. Therefore it is unlikely markers for renal function would have improved model fitting [48,66]. Other missing potential covariates included; serum albumin, urine pH, pharmacogenomic data, and concomitant drug use [67–70]. A second limitation is that the exact age of each infant during MTX infusion was not available, and therefore there may have been discrepancies between ages used for modeling and true age during infusion. A third limitation is that the MTX concentrations we chose as targets for our simulation have not been prospectively validated. Therefore, future studies are still needed to elucidate the relationship between MTX concentrations and both efficacy and toxicity. A fourth limitation of our analysis is that intensive PK sampling was not evenly distributed across treatment cycles, and this may limit our ability estimate true IOV in MTX CL across treatment cycles. Despite these limitations, our results add to the dearth of literature on the PK of MTX in infants with ALL, and provide additional evidence of the potential benefit of individualized dosing strategies.

In conclusion, we characterized the population PK of MTX in infants with ALL using a two-compartment model allometrically scaled by body size. Infants treated in our study demonstrated a relatively high degree of IOV in MTX CL across treatment cycles. These analyses suggest that individualization of MTX therapy may be improved by performing additional monitoring and dose adjustment during MTX infusions to account for the change in MTX CL occurring across treatment cycles.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig 1. Weight-normalized clearance values for all 71 infants versus a) post-natal age and b) treatment cycle. Each point represents the post-hoc estimate for individual subject clearance at each treatment cycle. The grey horizontal line represents the median weight normalized clearance of 0.273 L/h/kg.

Supplementary Fig. 2 Final model visual predictive check of the first 72 hours after dosing. A total of 44 points (7.2%) fell outside the 90% prediction interval. Dotted and solid lines represent the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the simulated data and observed data, respectively. Gray shaded areas represent the 90% prediction interval. The x-axis represents time after the start of the 24 hour methotrexate infusion. The y-axis represents plasma methotrexate concentrations on a log scale.

KEY POINTS:

High-dose methotrexate is a crucial component of treatment protocols for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), but few studies have characterized its disposition in infants.

Infants with ALL demonstrated significant interoccasion variability in their clearance of methotrexate across treatment cycles.

Monte Carlo simulations performed using a developed population pharmacokinetic model revealed the utility of bedside monitoring and dose adjustment to optimize methotrexate exposure.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Children’s Oncology Group Chair’s Grant U10CA098543 and Statistics & Data Center Grant U10CA098413, the NCTN Operations Center Grant U10CA180886, the NCTN Statistics & Data Center Grant U10CA180899, and by St. Baldrick’s Foundation. Authors P.A.T and R.C.V wish to acknowledge the contributions of Jeff Barrett, PhD, Head Quantitative Sciences at Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute and Peter L Bonate, PhD, Global Head, Pharmacokinetics, Modeling, and Simulation, Astellas Pharmaceuticals for their NONMEM and PK modeling education.

8. FUNDING

R.J.B. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award T32GM086330. M.F.H. is funded by a IQVIA Pharmacometrics Fellowship. D.G. receives support for research from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD083465). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH. The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts to disclose.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

RJ Beechinor, PA Thompson, RC Vargo, MF Hwang, LR Bomgaars, J Gerhart, Z Dreyer, and D Gonzalez declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014. National Cancer Institute.2016. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed 24 Apr 2018.

- 2.Terwilliger T, Abdul-Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inaba H, Greaves M, Mullighan C. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Lancet. 2013;381:1943–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieters R Infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Lessons learned and future directions. Pediatr Malig Hematol. 2009;4(3):167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilden JM, Dinndorf PA, Meerbaum SO, Sather H, Villaluna D, Heerema NA, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants: report on CCG 1953 from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2006;108(2):441–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palle J, Frost BM, Forestier E, Gustafsson G, Nygren P, Hellebostad M, et al. Cellular drug sensitivity in MLL-rearranged childhood acute leukaemia is correlated to partner genes and cell lineage. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(2):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotecha RS, Gottardo NG, Kees UR, Cole CH. The evolution of clinical trials for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4(4):e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleyer WA. Methotrexate: clinical pharmacology, current status and therapeutic guidelines. Cancer Treat Rev. 1977;4(2):87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleyer WA. The clinical pharmacology of methotrexate new applications of an old drug. Cancer. 1978;41(1):36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baram J, Allegra CJ, Fine RL, Chabner BA. Effect of methotrexate on intracellular folate pools in purified myeloid precursor cells from normal human bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 1987;79(3):692–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman D, Matherly LH, Goldman ID, Matherly LH. The cellular pharmacology of methotrexate. Pharmac Ther.1985;28(1):77–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D. High-dose methotrexate in the treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 1996;72(4):194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans WE, Crom WR, Abromowitch M, Dodge R, Look AT, Bowman WP, et al. Clinical pharmacodynamics of high-dose methotrexate in acute lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(8):471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard SC, McCormick J, Pui C-H, Buddington RK, Harvey RD. Preventing and managing toxicities of high-dose Methotrexate. Oncologist. 2016;21(12):1471–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Methotrexate injection [prescribing information]. Lake Forest, IL: Hospira Inc; November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huffman DH, Wan SH, Azarnoff DL, Hoogstraten B, Hogstraten B. Pharmacokinetics of methotrexate. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;14(4):572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holford N, Heo Y-AA, Anderson B. A pharmacokinetic standard for babies and adults. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(9):2941–2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel SE, Moran RG. Problems in the chemotherapy of cancer in the neonate. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1981;3(3):287–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milsap RL, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetics in the infant. Env Heal Perspec. 1994;102(Suppl 11):107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart C, Hampton E. Effect of maturation on drug disposition in pediatric patients. Clin Pharm. 1987;6(7):548–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLeod HL, Relling MV, Crom WR, Silverstein K, Groom S, Rodman JH, et al. Disposition of antineoplastic agents in the very young child. Br J Cancer. 1992;18:S23–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friis-Hansen BJ, Holiday M, Stapleton T, Wallace WM. Total body water in children. Pediatrics. 1951;7(3):321–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lönnerholm G, Valsecchi MG, De Lorenzo P, Schrappe M, Hovi L, Campbell M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in infants treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(5):596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donelli MG, Zucchetti M, Robatto A, Perlangeli V, D’Incalci M, Masera G, et al. Pharmacokinetics of HD-MTX in infants, children, and adolescents with non-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;24(3):154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development—part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2(4):e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Population Pharmacokinetics. 1999. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM072137.pdf. Accessed 24 Apr 2018.

- 27.Joerger M Covariate pharmacokinetic model building in oncology and its potential clinical relevance. AAPS J. 2012;14(1):119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson PA, Murry DJ, Rosner GL, Lunagomez S, Blaney SM, Berg SL, et al. Methotrexate pharmacokinetics in infants with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59(6):847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fotoohi K, Skärby T, Söderhäll S, Peterson C, Albertioni F. Interference of 7-hydroxymethotrexate with the determination of methotrexate in plasma samples from children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia employing routine clinical assays. J Chromatogr. 2005;B 817(2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skärby T, Jönsson P, Hjorth L, Behrentz M, Böjrk O, Forestier E, et al. High-dose methotrexate: on the relationship of methotrexate elimination time vs renal function and serum methotrexate levels in 1164 courses in 264 Swedish children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51(4):311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belz S, Frickel C, Wolfrom C, Nau H, Henze G. High-performance liquid chromatographic determination of methotrexate, 7-hydroxymethotrexate, 5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid, and folinic acid in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. J Chromatogr B. 1994;661(1):109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarkar D Lattice: Multivariate Data Visualization with R. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar D, Andrews F. latticeExtra: extra graphical utilities based on lattice. https://cran.rproject.org/package=latticeExtra. Published 2016. Accessed 24 Apr 2018.

- 34.Wickham H Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson BJ, Holford NHG. Mechanistic basis of using body size and maturation to predict clearance in humans. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(1):25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson MO, Sheiner LB. The importance of modeling interoccasion variability in population pharmacokinetic analyses. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1993;21(6):735–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kristoffersson AN, Friberg LE, Nyberg J. Inter occasion variability in individual optimal design. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015;42(6):735–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baverel PG, Savic RM, Karlsson MO. Two bootstrapping routines for obtaining imprecision estimates for nonparametric parameter distributions in nonlinear mixed effects models. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2011;38(1):63–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN, Jonsson N. PsN-Toolkit--a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79(3):241–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. Xpose--an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;58(1):51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans WE, Relling MV., Rodman JH, Crom WR, Boyett JM, Pui C-H. Conventional compared with individualized chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(8):499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Widemann BC, Adamson PC. Understanding and managing methotrexate nephrotoxicity. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foster JH, Bernhardt MB, Thompson PA, Smith EO, Schafer ES. Using a bedside algorithm to individually dose high-dose methotrexate for patients at risk for toxicity. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39(1):72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavielle M mlxR: Simulation of Longitudinal Data. R package version 3.3.0. https://cran.r-project.org/package=mlxR. Published 2018. Accessed 24 Apr 2018

- 45.Keizer RJ, Jansen RS, Rosing H, Thijssen B, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, et al. Incorporation of concentration data below the limit of quantification in population pharmacokinetic analyses. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2015;3(2):e00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wall AM, Gajjar A, Link A, Mahmoud H, Pui CH, Relling MV. Individualized methotrexate dosing in children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2000;14(2):221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paci A, Veal G, Bardin C, Levêque D, Widmer N, Beijnen J, et al. Review of therapeutic drug monitoring of anticancer drugs part 1 – Cytotoxics. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(12):2010–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aumente D, Buelga DS, Lukas JC, Gomez P, Torres A, García MJ. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(12):1227–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucchesi M, Guidi M, Fonte C, Farina S, Fiorini P, Favre C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in infants aged less than 12 months treated for aggressive brain tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77(4):857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piard C, Bressolle F, Fakhoury M, Zhang D, Yacouben K, Rietord A, et al. A limited sampling strategy to estimate individual pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60(4):609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buitenkamp TD, Mathôt RAA, de Haas V, Pieters R, Zwaan CM. Methotrexate-induced side effects are not due to differences in pharmacokinetics in children with Down syndrome and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(7):1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Min Y, Qiang F, Peng L, Zhu Z. High dose methotrexate population pharmacokinetics and Bayesian estimation in patients with lymphoid malignancy. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2009;30(8):437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe M, Fukuoka N, Takeuchi T, Yamuguchi K, Motoki T, Tanaka H, et al. Developing population pharmacokinetic parameters for high-dose methotrexate therapy: implication of correlations among developed parameters for individual parameter estimation using the bayesian least-squares method. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37(6):916–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jönsson P, Skärby T, Heldrup J, Schrøder H, Höglund P. High dose methotrexate treatment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia may be optimised by a weight-based dose calculation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dombrowsky E, Jayaraman B, Narayan M, Barrett JS. Evaluating performance of a decision support system to improve methotrexate pharmacotherapy in children and young adults with cancer. Ther Drug Monit. 2011;33(1):99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuhara K, Ikawa K, Morikawa N, Kumagai K. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in Japanese adult patients with malignancies: a concurrent analysis of the serum and urine concentration data. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33(6):677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rousseau A, Sabot C, Delepine N, Delepine G, Debord J, Lachâtre G, et al. Bayesian estimation of methotrexate pharmacokinetic parameters and area under the curve in children and young adults with localised osteosarcoma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(13):1095–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson B, Holford N. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48(303–32). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nader A, Zahran N, Alshammaa A, Altaweel H, Kassem N, Wilby KJ. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous methotrexate in patients with hematological malignancies: utilization of routine clinical monitoring parameters. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2017;42(2):221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faltaos DW, Hulot JS, Urien S, Morel V, Kaloshi G, Fernandez C, et al. Population pharmacokinetic study of methotrexate in patients with lymphoid malignancy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58(5):626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aquerreta I, Aldaz A, Giráldez J, Sierrasesúmaga L. Pharmacodynamics of high-dose methotrexate in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(9):1344–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Odoul F, Le Guellec C, Lamagnère JP, Breilh D, Saux MC, Paintaud G, et al. Prediction of methotrexate elimination after high dose infusion in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia using a population pharmacokinetic approach. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13(5):595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crews KR, Liu T, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Tan M, Meyer WH, Panette JC, et al. High-dose methotrexate pharmacokinetics and outcome of children and young adults with osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1724–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borsi JD, Schuler D, Moe PJ. Methotrexate administered by 6-h and 24-h infusion: a pharmacokinetic comparison. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1988;22(1):33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martelli N, Mathieu O, Margueritte G, Bozonnat MC, Daurès JP, Bressolle F, et al. Methotrexate pharmacokinetics in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A prognostic value? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(2):237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tiwari P, Thomas MK, Pathania S, Dhawan D, Gupta YK, Vishnubhatla S, et al. Serum creatinine versus plasma methotrexate levels to predict toxicities in children receiving high-dose methotrexate. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;32(8):576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reiss SN, Buie LW, Adel N, Goldman DA, Devlin SM, Doucer D. Hypoalbuminemia is significantly associated with increased clearance time of high dose methotrexate in patients being treated for lymphoma or leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(12):2009–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Relling BM V, Fairclough D, Ayers D, Crom WR, Rodman JH, Pui CH, et al. Patient characteristics associated with high-risk methotrexate concentrations and toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(8):1667–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rau T, Erney B, Göres R, Eschenhagen T, Beck J, Langer T. High-dose methotrexate in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Impact of ABCC2 polymorphisms on plasma concentrations. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(5):468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reeves DJ, Moore ES, Bascom D, Rensing B. Retrospective evaluation of methotrexate elimination when co-administered with proton pump inhibitors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(3):565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig 1. Weight-normalized clearance values for all 71 infants versus a) post-natal age and b) treatment cycle. Each point represents the post-hoc estimate for individual subject clearance at each treatment cycle. The grey horizontal line represents the median weight normalized clearance of 0.273 L/h/kg.

Supplementary Fig. 2 Final model visual predictive check of the first 72 hours after dosing. A total of 44 points (7.2%) fell outside the 90% prediction interval. Dotted and solid lines represent the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the simulated data and observed data, respectively. Gray shaded areas represent the 90% prediction interval. The x-axis represents time after the start of the 24 hour methotrexate infusion. The y-axis represents plasma methotrexate concentrations on a log scale.