Abstract

Naïve T cell activation requires antigen presentation combined with costimulation through CD28, both of which optimally occur in secondary lymphoid tissues such as lymph nodes and the spleen. Belatacept impairs CD28 costimulation by binding its ligands, CD80 and CD86, and in doing so, impairs de novo alloimmune responses. However, in most patients belatacept is ineffective in preventing allograft rejection when used as a monotherapy, and adjuvant therapy is required for control of costimulation-blockade resistant rejection (CoBRR). In rodent models, impaired access to secondary lymphoid tissues has been demonstrated to reduce alloimmune responses to vascularized allografts. Here we show that surgical maneuvers, lymphatic ligation and splenectomy, designed to anatomically limit access to secondary lymphoid tissues, control CoBRR, and facilitate belatacept monotherapy in a nonhuman primate model of kidney transplantation without adjuvant immunotherapy. We further demonstrate that animals sustained on belatacept monotherapy progressively develop an increasingly naïve T and B cell repertoire, an effect that is accelerated by splenectomy and lost at the time of belatacept withdrawal and rejection. These pilot data inform the role of secondary lymphoid tissues on the development of CoBRR and the use of costimulation molecule–focused therapies.

Introduction

Renal transplantation has long been the preferred therapy for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), improving both morbidity and mortality over the alternative of dialysis (1). Successful acceptance of a renal allograft requires long-term immunosuppression, and over 90% of patients rely on the use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) (2). CNIs indiscriminately impair T cell receptor (TCR) function and as such impair protective immune function as well as alloimmune recognition. They also target broad metabolic pathways evoking morbid off-target effects, particularly nephrotoxicity. Optimal antigen presentation requires, in addition to the antigen–TCR interaction, CD28-CD80/86 costimulation. As such, costimulation pathway inhibition has also been shown to promote allograft acceptance, and when used without a CNI, do so with fewer side effects than CNIs (3–6). However, generalized adoption of costimulation blockade (CoB)–based immunotherapy has been limited in part due to its inability to control early acute rejection, referred to as costimulation-blockade resistant rejection (CoBRR) (7). Thus, broader adoption of CoB-based immunosuppressive regimens in renal transplantation require strategies to prevent or reduce the rate of CoBRR.

Antigen presentation to the TCR, and CD28 costimulation, are optimally delivered in the context of secondary lymphoid structures such as the spleen and lymph nodes (8–11). In particular, careful study in animal models has revealed that the development of an alloimmune response to a vascularized organ transplant begins most efficiently in secondary lymphoid structures, suggesting that trafficking of donor antigen, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and effector cells to and from these structures accelerates de novo alloimmune responses following transplantation (8). This insight has prompted examination of strategies to modulate lymphatic trafficking as an adjunct to CoB. Pharmacologic manipulation of lymphatic trafficking after transplantation is possible, and many agents have demonstrated efficacy in pre-clinical models of cellular transplantation including models using CoB (12–16). However, these strategies have inconsistently prevented renal allograft rejection, suggesting that the reperfusion events inherent to vascularized allografts evoke more stimulus for CoBRR than in cellular grafts (17).

Splenectomy has been used as a maneuver to delay or prevent the development of antibody in high-risk recipients (18), and has been employed as part of a multimodal strategy to improve allograft function and prevent graft loss following development of antibody-mediated rejection (19). Likewise, splenic irradiation has recently been described as a means to treat severe antibody-mediated rejection (20), and has been a part of several tolerance regimens in non-human primates (21, 22) and in humans (23). However, to date no studies have examined the contribution of splenectomy to a CoB-based immunosuppression regimen. Similarly, the surgical techniques of kidney engraftment largely ignore efferent lymphatics, leaving the recanalation of renal lymphatics and egress of lymph from an allograft to chance (24). Given that CoB-based regimens aim to impair events that canonically occur in secondary lymphoid tissues, we have posited that a more explicit approach toward strategies such as splenectomy may synergize with CoB to promote allograft acceptance.

To examine the role of the spleen in thwarting CoB-based immunotherapy, we tested the hypothesis that the addition of splenectomy in a rigorous preclinical nonhuman primate model of renal transplantation would decrease the observed rate of CoBRR. We demonstrate that the addition of splenectomy to CoB-based immunotherapy reduces the rate of CoBRR and improves rejection-free survival, suggesting that the addition of splenectomy or a less invasive approach toward impairment of secondary lymphoid tissue function following renal transplantation may warrant further study and permit further adoption of CoB-based immunosuppressive strategies in appropriately-selected candidates.

Materials and Methods

Rhesus renal transplantation and monitoring

All experiments performed in this study were conducted with the approval of the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in adherence with the principles laid out in The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, DHHS) (25). Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were obtained from breeding colonies at AlphaGenesis, Inc. (Yemassee, SC, USA). Donor-recipient pairs were determined by maximal MHC disparity with a minimum of 3 major antigen mismatches and secondarily by similar size. MHC typing for both class I and class II was performed by 454 pyrosequencing (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA).

Transplantation was performed in a domino fashion to maximize the utility of the available animals, with each animal serving as a kidney donor prior to receiving a transplant as described previously (15, 17, 26, 27). Left donor nephrectomy was performed at least 3 weeks prior to transplantation. A right nephrectomy was simultaneously conducted after implantation to leave each recipient entirely dependent on the allograft. Animals in the experimental condition underwent open splenectomy immediately prior to allograft implantation on the day of the recipient operation. To control for variability in the lymphatic drainage from the transplant allograft, in experimental transplants all draining lymphatics were meticulously ligated with a combination of suture ligation and hemo-clip placement at the time of procurement, as opposed to the standard use of sharp dissection. Post-transplant monitoring consisted of daily clinical assessment by veterinary staff, as well as laboratory studies including serum chemistry and complete blood count assessments performed 2–4 times monthly, or more often if dictated by clinical condition. Rhesus CMV (rhCMV) was monitored with every blood draw and when clinically indicated using qPCR. CMV Prophylaxis was initiated at the time of transplant for all control and experimental animals, which consisted of valganciclovir 60 mg twice daily, with viral copies >10,000/mL treated with the addition of IM ganciclovir 5–7.5 mg/kg twice daily. Experimental endpoint was determined by significant and sustained increase in serum creatinine confirmed over two days. Humane endpoints were implemented when necessary after consultation with veterinary staff.

Post-Transplant Immunosuppression

All animals (experimental and control) received identical immunosuppressive regimens post-transplant; animals differed only in the receipt of open splenectomy and explicit attention to the renal hilar lymphatics as described above. Recipients received belatacept at 20mg/kg on the day of transplant, on post-operative days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, then every two weeks. At POD182, belatacept dose was weaned to 10mg/kg. Immunosuppression was entirely discontinued after a final dose on POD364. All recipients in this study received a single dose of methylprednisolone 15mg/kg intraoperatively immediately prior to allograft implantation.

Polychromatic flow cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from transplant recipients immediately prior to transplantation (POD 0) and immediately prior to every belatacept infusion outlined above. After washing with PBS and lysis of RBC, cells were stained with the following antibodies: CD3, CD4, CD2, CD28, CD95, CD11a, CD16, CD20, CD56, CD45, FoxP3, CD25, CD127, Ki67, and Bcl2. T-cell memory compartments were defined for analysis based on CD28 and CD95 expression following identification of CD3+CD4+ or CD3+CD8+ T-cells. CD28 and CD95 gating to identify naïve (CD28+CD95-), central memory (CD28+CD95+) and effector memory (CD28-CD95+) was employed as previously described(28, 29). A separate panel for the determination of B-cell phenotype incorporated IgD, CD21, IgM, CD138, CD38, CD20, CD19, and CD27. B-cell maturation was assessed as follows: Naïve (IgD+CD27-), Unswitched Memory (IgD+CD27+), Switched Memory (IgD-CD27+) and Exhausted (IgD-CD27-). As the B-cell analysis panel used in this study was developed and validated subsequent to the first control transplants reported in this study, we thawed banked PBMC’s at select time points (baseline and at time points reflecting stability on immunotherapy) as representative time points to examine changes in B-cell phenotype in this control group. Finally, assessment of the development of donor-specific antibody (DSA) was measured by flow cytometric crossmatch. Positive crossmatch was defined by MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) > 1000. Samples were acquired with an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 10; FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

At the time of rejection and recipient euthanasia, PBMCs were also collected in addition to lymph nodes and spleen tissue. Cells were isolated from these lymphoid organs through mechanical disassociation and passage of cells though a 70um filter. The resulting cells were lysed and stained for flow cytometry using the methods described above. The absolute cell counts were calculated from the percentages cell populations out of the relevant parent population by flow cytometry analysis and multiplied by the absolute cell counts for all lymphocytes.

Histology

At the time of recipient endpoint, lymph nodes, spleen, and the allograft were collected in 10% formalin for histological evaluation. These samples were embedded in paraffin with subsequent sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Needle-core biopsies were also obtained for animals with potential rejection without meeting the requirements for humane euthanasia. Images were digitally scanned using Aperio Scanscope AT Turbo (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (GraphPad; La Jolla, CA). Analysis of ex vivo data were performed with two-way ANOVAs. Allograft survival was compared using Kaplan-Meier analysis (Log-rank) of graft rejection. Longitudinal analysis of flow cytometry was performed using two-way ANOVA. Histology scoring was compared using a Chi squared test.

Results

Addition of splenectomy confers a survival advantage to costimulatory-blockade-based immunotherapy

A total of N=7 animals underwent splenectomy and hilar lymphatic control at the time of renal transplantation as described in methods. A control group that did not receive splenectomy and had standard hilar dissection consisted of N=10 animals, with N=5 performed contemporarily and N=5 combined for analysis from previously published work (15). Rejection-free survival was measured at a time of one-year post-transplant. There was no significant difference in rejection-free survival between the historic and contemporary control animals. The addition of splenectomy to the belatacept maintenance immunotherapy regimen significantly improved rejection-free survival. The median survival for the belatacept monotherapy control group was 81 days, while the median survival for the belatacept plus splenectomy group was undefined given the substantially prolonged survival (P = 0.027 by log-rank test, figure 1). Two animals in the splenectomy group were censored from analysis due to non-rejection endpoints: one animal at postoperative day 30 for weight loss and one animal at postoperative day 156 for renal venous outflow obstruction. Careful third-party review by an attending transplant pathologist to ascertain the absence of histologic evidence of rejection that may have contributed to these endpoints was performed in order to guide the decision to censor these animals for non-rejection endpoints, thereby permitting analysis of the animals’ phenotypic flow cytometry data and survival time in to the primary analyses. In accordance with guidance from our veterinary staff, we impose strict guardrails on weight loss for animals on all our nonhuman primate studies. Animals that do not maintain weight (or, that do not gain an age-appropriate amount of weight) are monitored closely for adequate nutrition, and assessed for potential causes (infectious or otherwise). Animals that do not respond adequately to supportive measures may not remain on the study protocol. In the study at hand, this censored animal is the only to have been unable to maintain weight, though we have observed this in other experiments. Animals that survived to one-year rejection-free underwent immunosuppression withdrawal. Of the four animals in the splenectomy group that reached one year rejection-free on belatacept monotherapy, three animals rejected their allografts within 90 days of immunosuppression withdrawal, indicating that while the addition of splenectomy facilitated CoB–based immune management, it did not obviate the need for long-term maintenance immunotherapy. No animals succumbed to overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis or CMV viremia.

Figure 1.

Rejection-free survival. Median survival time for untreated (historic) control was 7 days, for belatacept-alone group 81 days, and undefined for the belatacept + Splenectomy treatment group. Improvement in survival is significant by log-rank test (P = 0.027).

Costimulation blockade dependent graft survival is associated with a predominantly naïve lymphocyte phenotype

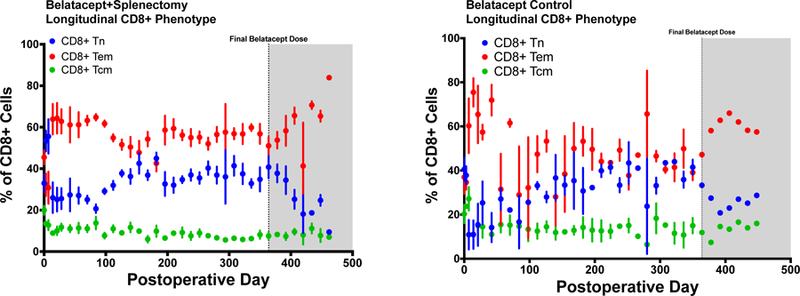

Animals in both treatment groups exhibited stable lymphocyte counts post-transplant, without significant differences between treatment groups while receiving maintenance immunosuppression (figure 2). Differences in T- and B-cell compartments were assessed and reported here as relative fractions given the stability of the total lymphocyte count post-transplant. Animals in both treatment groups developed a tendency towards early CD4+ naïvete’ (figures 3a and 3b), with a more prompt and consistent accumulation of naïve T-cells for animals that underwent splenectomy in comparison to animals in the control group. Inspection of the longitudinal T- and B-cell and memory-compartment subgroup trends of individual animals that experienced rejection (N=1 for splenectomy and lymphoid isolation) did not identify a unique peripheral phenotype associated with CoBRR in the setting of splenectomy and lymphoid isolation. The CD8+ phenotype across memory compartments did not differ significantly between treatment groups across longitudinal time points (figure 4a+b). Both CD4 and CD8 T cell phenotypes were more variable in the control group than the splenectomy group, given the episodic expansions of effector cells at the time of the numerous rejections in the control animals that were not seen in the splenectomy animals until immunosuppressive withdrawal. Investigation of the longitudinal phenotype of B-cell populations was also performed. Animals that underwent splenectomy at the time of transplantation demonstrated a gradual accumulation of naïve B-cells, depicted in figure 5. Both experimental and control treatment groups exhibited a tendency towards a Bnaïve phenotype at late time points, suggesting that the effect observed may be more driven by CoB-based immunotherapy rather than the addition of splenectomy at the time of transplantation. Finally, measurement of donor-specific antibody (DSA) revealed that no animals developed class I antibodies during belatacept therapy, consistent with clinical trial experience in human studies(30). One animal in each experimental condition developed class II antibody, though this development of antibody did not impact allograft survival, as neither animal developed acute rejection during belatacept therapy.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal absolute lymphocyte count. For both groups, absolute lymphocyte count remains stable longitudinally. No significant differences were observed in baseline nor in longitudinal absolute lymphocyte count during belatacept maintenance immunosuppression. Following complete immunosuppression withdrawal, the surviving animal in the belatacept control group exhibited modestly increased lymphocyte counts in comparison to animals that had received splenectomy at the time of transplantation.

Figure 3a+b.

(A) longitudinal relative distribution of CD4+ Tnaïve, Tcentral memory, and Teffector cells for animals that received splenectomy at the time of transplantation. Relative to the longitudinal distribution of control belatacept animals in (B), animals that underwent splenectomy exhibited a more prompt and prominent tendency towards a CD4+ Tnaïve predominance.

Figure 4a+b.

(A) longitudinal relative distribution of CD8+ Tnaïve, Tcentral memory, and Teffector cells for animals that received splenectomy at the time of transplantation. Relative to the longitudinal distribution of control belatacept animals in (B), animals that underwent splenectomy exhibited a less prominent tendency towards CD8+ Tem predominance early, though no significant difference between groups was identified in any memory compartment across later time points.

Figure 5.

Longitudinal relative distribution of B cells for animals that received splenectomy in addition to belatacept maintenance immunosuppression. In the first months post-transplant, animals that received a splenectomy at the time of transplantation subsequently developed a naïve B-cell predominance.

Discussion

Costimulation blockade resistant rejection remains a significant obstacle to the broad clinical application of CoB-based therapies, particularly belatacept(3, 31, 32). It is also relevant to the implementation of tolerance induction regimens, which increasingly include CoB as a component, along with varying degrees of secondary lymphoid irradiation (21–23). In this study, we demonstrate that the addition of splenectomy to CoB-based immunotherapy decreases the rate of CoBRR and improves rejection-free survival on belatacept monotherapy. This observation is consistent with the prevailing understanding of costimulation molecules, specifically, that they facilitate antigen presentation, and with the premise that antigen presentation following a primarily vascularized allograft occurs in secondary lymphoid structures, including the spleen (8).

The development of any de novo response to antigen requires the physical co-localization of APCs and lymphocytes. This occurs most efficiently in secondary lymphoid structures, where APCs organize and lymphocytes traffic (11). These structures increase the likelihood of physical co-localization and provide the architectural context which favors the development of an immune response. Though axiomatic, this basic immunological principle is infrequently considered in clinical transplantation. Indeed, substantial focus is directed toward the allograft as the source of alloimmune sensitization, and lymphatics emerging from the allograft are generally ignored, leaving their reconnection to chance, and the resorption of graft-derived lymph indeterminant (24). To our knowledge, this is the first explicit assessment of how access to the spleen or donor lymphatics influences CoBRR.

Several studies have demonstrated the critical nature of secondary lymphoid organs in organ allograft rejection. Larsen, et al, first demonstrated in a mouse heterotopic heart transplant model that graft-derived APCs traffic to the spleen and that this is necessary for the development of an alloimmune response (8, 33). Lakkis, et al, examined immunologic ‘ignorance’ of a vascularized graft in the setting of splenectomized, conditional knockout mice that lacked all secondary lymphoid structures (34). These insights spurred substantial investigation of pharmacologic strategies to modulate lymphocyte trafficking in the setting of transplantation. Although promising for cellular grafts, the outcomes for primarily vascularized grafts (35), particularly in the setting of CoB have been discouraging (15, 35). Outside of transplantation, other similar contexts of immunologic ignorance such as pregnancy have been shown to require modulation of lymphoid trafficking as a means to decrease the likelihood of development of untoward immune responses to the maturing fetus (36). Taken together, these data suggest that efficient antigen presentation by way of secondary lymphoid structures is critical to the timely development of an immune response, and that manipulation of this relationship could be anticipated to augment contemporary immunosuppressive strategies.

The addition of splenectomy to CoB-based immunotherapy described in this work facilitates long-term allograft acceptance and permits CoB monotherapy without reliance on potentially more morbid strategies such as therapeutic lymphocyte depletion or the addition of secondary immunomodulating agents. The addition of splenectomy was well-tolerated, with no evidence of the loss of ability to control endogenous virus, as has been observed in the setting of more profound immunosuppressive strategies (26). In our studies, as in both clinical and preclinical models of CoB-based immunotherapy, long-term allograft acceptance has been characterized by a preponderance of Tnaïve CD4+ cells, which come to represent a majority of peripheral circulating T-cells post-transplant (15, 37–39). This is consistent with the efficacy of CoB in preventing the maturation of naïve T cells, combined with ongoing T cell turnover and elimination of terminally differentiated cells over time. As there were no overt changes in absolute lymphocyte counts, we favor the interpretation that splenectomy accentuates the limitations of CoB to prevent maturation, rather than directly eliminates T cells or exerts its effects through lymphopenia. Though difficult to statistically describe, splenectomy was associated with reduced longitudinal variability in both CD4 and CD8 T cell phenotype. We interpret this to relate to the progressive development of allograft rejection in control group, with its accompanying expansion of allospecific effectors. However, limits placed on lymphoid trafficking could more generally govern effector T cell maturation and contribute directly to a more stable peripheral phenotype. The analysis of the B-cell phenotype in this study reveals a similar tendency for long-term survivors to exhibit a more stable, progressively naïve B-cell signature, one that is similar to that observed in tolerant recipients of renal allografts (40–43). As animals do not receive treatment for rejection in this model, our ability to truly tease out the causal relationship between allograft acceptance and these naïve phenotypes is limited, particularly in that long-term phenotypes are biased towards those that stably accept allografts. Nevertheless, animals that rejected after withdrawal of belatacept had a marked accumulation of effector and more terminally differentiated cells.

A natural extension of the data reported in the present work lies in the establishment of cell populations directly impacted by the addition of splenectomy and lymphoid isolation in the setting of costimulatory blockade. In previous work, we have recently reported on the identification of a CD57+ CD4+ T-cell population that expresses a nonsenescent, cytolytic phenotype and is implicated in experimental CoBRR(44). Further work is ongoing to establish the prognostic significance of these CD57+CD4+ T-cells in the setting of CoB Resistant-Rejection in renal allotransplantation. The relationship between this cell population and lymphoid trafficking between the allograft and secondary lymphoid organs is not yet defined. At present, there are no antibodies that define this antigen in rhesus. Moving forward, experimental models that are able to better assess lymphatic trafficking of these specific cells may yield further insights into the mechanistic nature of CoBRR as well as further characterize the impact of splenectomy and lymphoid isolation in the setting of renal allotransplantation.

As with all preclinical models, the data described here should be evaluated in the context of certain limitations. Though this model has been employed extensively by a community of investigators and has been found to be a high-fidelity model of the human renal allotransplantation experience, this model best recapitulates a living-donor approach in young and immunologically naïve animals without a prior history of renal disease. While these animals do not perfectly reflect the standard transplant recipient in clinical practice, the experimental design employed – particularly with respect to maximal MHC disparity – represents a model in which the tendency towards allograft rejection is high and as such our studies are very sensitive to the development of rejection. Promising results from this model then have high potential to succeed when applied to human transplantation with overall lower immunologic barriers on account of lower degrees of MHC disparity. We acknowledge that the role of our ligation of hilar lymphatics is challenging to ascertain. We assume that direct ligation of the lymphatics reduces the likelihood of lymphatic egress. However, from experience, the degree to which indifference toward the hilar lymphatics influences their recanalization is random, with lymphatics variably closed, open or able to reestablish heterotopic drainage. As there is not a way to control for the fate of lymphatic drainage in non-ligated animals, this element of the experiment remains unresolved. It is plausible that failed recanalization in the control animals segregates to the subset of animals that do not develop CoBRR. To date, we have not been able to address this experimentally, and it thus remains a point worthy of additional investigation, likely in a small animal setting. Finally, note is made of the need to censor two animals from the final analysis as described in results. Though the decision to censor animals for non-rejection endpoints fits with our a priori decision to measure rejection-free survival in this experimental model and was made with the guidance of external assessment, this decision does not establish if these non-rejection endpoints were related to the experimental condition tested in this work, or related to the model in general. While we do not have evidence to suggest that the observed endpoints were directly related to splenectomy and lymphoid isolation (and weight loss has been previously observed in other studies that employ a nonhuman renal allotransplantation model), careful attention is warranted in further studies of these maneuvers to ascertain if these complications arise at a significantly higher rate than that observed in the present work.

While pharmacologic manipulation of lymphoid trafficking alone has not to date been successful in preventing CoBRR, we describe here simple physical maneuvers that may decrease the efficiency of costimulation delivery through antigen presentation, and in so doing, facilitate CoB-based immunotherapy, alloimmune response control and long-term allograft acceptance. However, under standard surgical techniques for renal allotransplantation in humans, the peritoneal cavity is not entered. As such, the appropriate risk-benefit relationship must be carefully outlined when considering broader adoption of such a strategy for use in human transplantation. Regardless, these studies may inform the degree to which total lymphoid irradiation and other maneuvers designed to target the spleen may have in fostering a rejection-free state. Situations such as the transplant candidate with complex vascular comorbidities or those otherwise requiring the placement of an intra-abdominal allograft may be the best candidates for the initial consideration of such a maneuver, or patients in which the spleen has been removed for another indication. Likewise, control of the spleen by way of embolization or irradiation – previously described in the setting of transplantation – may provide a means to achieve similar results but without the added complexity of a surgical procedure (20). Further study in preclinical models may yield additional insight into the feasibility of such a strategy in the setting of CoB-based immunotherapy for renal transplantation.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH grant #U19-AI051731 (ADK) and F32-HL132460-02 (MSM). We would also like to thank the Duke University Substrate Core for their assistance in CMV monitoring.

Abbreviations

- CoB

Costimulation Blockade

- CoBRR

Costimulation Blockade Resistant Rejection

- DSA

Donor-Specific Antibody

- NHP

Non-Human Primate

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. The New England journal of medicine 1999;341(23):1725–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Stewart DE, Cherikh WS et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant 2017;17 Suppl 1:21–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, Rostaing L, Bresnahan B, Darji P et al. A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study). Am J Transplant 2010;10(3):535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferguson R, Grinyo J, Vincenti F, Kaufman DB, Woodle ES, Marder BA et al. Immunosuppression with belatacept-based, corticosteroid-avoiding regimens in de novo kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2011;11(1):66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pestana JO, Grinyo JM, Vanrenterghem Y, Becker T, Campistol JM, Florman S et al. Three-year outcomes from BENEFIT-EXT: a phase III study of belatacept versus cyclosporine in recipients of extended criteria donor kidneys. Am J Transplant 2012;12(3):630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naesens M, Thaunat O. Transplantation: BENEFIT of belatacept: kidney transplantation moves forward. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016;12(5):261–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masson P, Henderson L, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Webster AC. Belatacept for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(11):CD010699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen CP, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Migration of dendritic leukocytes from cardiac allografts into host spleens. A novel pathway for initiation of rejection. J Exp Med 1990;171(1):307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Thery C, Amigorena S. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2002;20:621–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emmanouilidis N, Guo Z, Dong Y, Newton-West M, Adams AB, Lee ED et al. Immunosuppressive and trafficking properties of donor splenic and bone marrow dendritic cells. Transplantation 2006;81(3):455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neely HR, Flajnik MF. Emergence and Evolution of Secondary Lymphoid Organs. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2016;32:693–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvadori M, Budde K, Charpentier B, Klempnauer J, Nashan B, Pallardo LM et al. FTY720 versus MMF with cyclosporine in de novo renal transplantation: a 1-year, randomized controlled trial in Europe and Australasia. Am J Transplant 2006;6(12):2912–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tedesco-Silva H, Pescovitz MD, Cibrik D, Rees MA, Mulgaonkar S, Kahan BD et al. Randomized controlled trial of FTY720 versus MMF in de novo renal transplantation. Transplantation 2006;82(12):1689–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoitsma AJ, Woodle ES, Abramowicz D, Proot P, Vanrenterghem Y, Group FTYPITS. FTY720 combined with tacrolimus in de novo renal transplantation: 1-year, multicenter, open-label randomized study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26(11):3802–3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samy KP, Anderson DJ, Lo DJ, Mulvihill MS, Song M, Farris AB et al. Selective Targeting of High-Affinity LFA-1 Does Not Augment Costimulation Blockade in a Nonhuman Primate Renal Transplantation Model. Am J Transplant 2017;17(5):1193–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khiew SH, Yang J, Young JS, Chen J, Wang Q, Yin D et al. CTLA4-Ig in combination with FTY720 promotes allograft survival in sensitized recipients. JCI Insight 2017;2(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson DJ, Lo DJ, Leopardi F, Song M, Turgeon NA, Strobert EA et al. Anti-Leukocyte Function-Associated Antigen 1 Therapy in a Nonhuman Primate Renal Transplant Model of Costimulation Blockade-Resistant Rejection. Am J Transplant 2016;16(5):1456–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okiye SE, Zincke H, Engen DE, Sterioff S, Offord KP, Frohnert PP et al. Splenectomy in high-risk primary renal transplant recipients. Am J Surg 1983;146(5):594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orandi BJ, Zachary AA, Dagher NN, Bagnasco SM, Garonzik-Wang JM, Van Arendonk KJ et al. Eculizumab and splenectomy as salvage therapy for severe antibody-mediated rejection after HLA-incompatible kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2014;98(8):857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orandi BJ, Lonze BE, Jackson A, Terezakis S, Kraus ES, Alachkar N et al. Splenic Irradiation for the Treatment of Severe Antibody-Mediated Rejection. Am J Transplant 2016;16(10):3041–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai T, Abrahamian G, Sogawa H, Wee S, Boskovic S, Andrew D et al. Costimulatory blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in nonhuman primates. Transplantation proceedings 2001;33(1–2):221–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada Y, Ochiai T, Boskovic S, Nadazdin O, Oura T, Schoenfeld D et al. Use of CTLA4Ig for induction of mixed chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant 2014;14(12):2704–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scandling JD, Busque S, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Benike C, Millan MT, Shizuru JA et al. Tolerance and chimerism after renal and hematopoietic-cell transplantation. The New England journal of medicine 2008;358(4):362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranghino A, Segoloni GP, Lasaponara F, Biancone L. Lymphatic disorders after renal transplantation: new insights for an old complication. Clin Kidney J 2015;8(5):615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Research Council (U.S.). Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals., Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.), National Academies Press (U.S.). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals In. 8th ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press,, 2011: xxv, 220 p. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo DJ, Anderson DJ, Weaver TA, Leopardi F, Song M, Farris AB et al. Belatacept and sirolimus prolong nonhuman primate renal allograft survival without a requirement for memory T cell depletion. Am J Transplant 2013;13(2):320–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo DJ, Anderson DJ, Song M, Leopardi F, Farris AB, Strobert E et al. A pilot trial targeting the ICOS-ICOS-L pathway in nonhuman primate kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2015;15(4):984–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaccari M, Trindade CJ, Venzon D, Zanetti M, Franchini G. Vaccine-induced CD8+ central memory T cells in protection from simian AIDS. J Immunol 2005;175(6):3502–3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitcher CJ, Hagen SI, Walker JM, Lum R, Mitchell BL, Maino VC et al. Development and homeostasis of T cell memory in rhesus macaque. J Immunol 2002;168(1):29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bray RA, Gebel HM, Townsend R, Roberts ME, Polinsky M, Yang L et al. De novo donor-specific antibodies in belatacept-treated vs cyclosporine-treated kidney-transplant recipients: Post hoc analyses of the randomized phase III BENEFIT and BENEFIT-EXT studies. Am J Transplant 2018;18(7):1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durrbach A, Pestana JM, Pearson T, Vincenti F, Garcia VD, Campistol J et al. A phase III study of belatacept versus cyclosporine in kidney transplants from extended criteria donors (BENEFIT-EXT study). Am J Transplant 2010;10(3):547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincenti F, Rostaing L, Grinyo J, Rice K, Steinberg S, Gaite L et al. Belatacept and Long-Term Outcomes in Kidney Transplantation. The New England journal of medicine 2016;374(4):333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen CP, Morris PJ, Austyn JM. Donor dendritic leukocytes migrate from cardiac allografts into recipients’ spleens. Transplantation proceedings 1990;22(4):1943–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakkis FG, Arakelov A, Konieczny BT, Inoue Y. Immunologic ‘ignorance’ of vascularized organ transplants in the absence of secondary lymphoid tissue. Nat Med 2000;6(6):686–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badell IR, Russell MC, Thompson PW, Turner AP, Weaver TA, Robertson JM et al. LFA-1-specific therapy prolongs allograft survival in rhesus macaques. The Journal of clinical investigation 2010;120(12):4520–4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins MK, Tay CS, Erlebacher A. Dendritic cell entrapment within the pregnant uterus inhibits immune surveillance of the maternal/fetal interface in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2009;119(7):2062–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirk AD, Harlan DM, Armstrong NN, Davis TA, Dong Y, Gray GS et al. CTLA4-Ig and anti-CD40 ligand prevent renal allograft rejection in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997;94(16):8789–8794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montgomery SP, Xu H, Tadaki DK, Celniker A, Burkly LC, Berning JD et al. Combination induction therapy with monoclonal antibodies specific for CD80, CD86, and CD154 in nonhuman primate renal transplantation. Transplantation 2002;74(10):1365–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu H, Samy KP, Guasch A, Mead SI, Ghali A, Mehta A et al. Postdepletion Lymphocyte Reconstitution During Belatacept and Rapamycin Treatment in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant 2016;16(2):550–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newell KA, Asare A, Kirk AD, Gisler TD, Bourcier K, Suthanthiran M et al. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. The Journal of clinical investigation 2010;120(6):1836–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chesneau M, Pallier A, Braza F, Lacombe G, Le Gallou S, Baron D et al. Unique B cell differentiation profile in tolerant kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2014;14(1):144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rebollo-Mesa I, Nova-Lamperti E, Mobillo P, Runglall M, Christakoudi S, Norris S et al. Biomarkers of Tolerance in Kidney Transplantation: Are We Predicting Tolerance or Response to Immunosuppressive Treatment? Am J Transplant 2016;16(12):3443–3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newell KA, Adams AB, Turka LA. Biomarkers of operational tolerance following kidney transplantation - The immune tolerance network studies of spontaneously tolerant kidney transplant recipients. Hum Immunol 2018;79(5):380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Espinosa J, Herr F, Tharp G, Bosinger S, Song M, Farris AB 3rd et al. CD57(+) CD4 T Cells Underlie Belatacept-Resistant Allograft Rejection. Am J Transplant 2016;16(4):1102–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]