Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To provide an overview of the presenting features, etiologies, and outcomes of children enrolled in the Drug-induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) prospective and retrospective studies.

METHODS

Consecutive definite, highly likely, or probable cases in children enrolled into the ongoing DILIN prospective and retrospective studies between 9/04 and 2/17 were reviewed.

RESULTS

57 cases were adjudicated as definite (14), highly likely (30), or probable (13) DILI. Median age was 14.3 years (1.7–17.9), 67% female, and 82% Caucasian. At DILI onset, 82% had hepatocellular injury with a median alanine aminotransferase of 411 U/L (33–4185), alkaline phosphatase 203 U/L (62–1177), and total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (0.2–33.9). The median duration of suspect medication use was 55 days (1–2789) and the most frequently implicated individual agents were minocycline (n=11) and valproate (n=6). 63% were hospitalized and 3 (5%) underwent liver transplant within 1 month of DILI onset. Among 46 children followed for at least 6 months, 8 (17%) met criteria for chronic DILI with 6 of them having persistent liver injury at 24 months of follow-up. A genome wide association study in 39 Caucasian children focusing on regions associated with pediatric cholestatic liver disease failed to demonstrate any single nucleotide polymorphism associated with DILI susceptibility or outcome.

Conclusions

Antimicrobials (51%) and antiepileptic drugs (21%) are the most frequently implicated agents in pediatric DILI patients. While the majority of cases are self-limited, there is potential for serious morbidity including acute liver failure, chronic liver injury, and death.

Keywords: hepatotoxicity, drug induced liver injury, liver transplantation, medication

INTRODUCTION

Idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury (DILI) is an infrequent but increasingly recognized cause of potentially severe acute and chronic liver disease. The incidence of idiosyncratic DILI in the general adult population is estimated to be 13.9 to 19.1 per 100,000 (1, 2). The incidence of DILI among children is lower presumably due to the fact that children are prescribed medications less often than adults (i.e. less exposure) (2). However, other factors such as differences in drug metabolism and disposition may also play a role in the differing incidence and etiologies of DILI in children compared to adults (3). Despite its low incidence, pediatric DILI has been associated with substantial short and long-term morbidity and mortality (4–7).

The Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) was developed in 2003 to improve our understanding of the etiologies, suspect drugs, and outcomes of children and adults with DILI in the United States (8). Recently, DILIN and others have identified several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes and other alleles associated with DILI susceptibility in general as well as in patients receiving individual drugs (9–11). In 2009, an analysis of 26 consecutive cases of pediatric DILI enrolled in the US DILIN prospective registry were reported (12). Herein, we present the clinical features, liver histology, and long-term clinical outcomes of 57 high causality pediatric cases enrolled into the ongoing prospective and retrospective DILIN registry studies. In addition, we report the results of a genome wide association study (GWAS) in 39 Caucasian children focused on the region associated with various pediatric liver diseases.

METHODS

The DILIN is an ongoing multicenter study of 6 clinical sites and a data coordinating center sponsored by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (8). For the prospective study, eligible individuals must be enrolled within 6 months of liver injury onset attributed to any drug or herbal and dietary supplement (HDS) product. In addition, all subjects must meet minimum laboratory criteria (See supplemental Text). Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all subjects (or legal next of kin) as appropriate.

Causality assessment and Liver Injury Severity

The DILIN prospective and retrospective studies use an expert opinion based causality assessment method (8, 13). The pattern of liver injury at DILI onset is categorized by the R ratio (i.e. serum ALT over the ULN divided by the serum Alk P over the ULN) with hepatocellular defined as an R≥5, mixed as 2<R<5, and cholestatic as R≤2. Each investigator was assigned an expert opinion causality score representing the likelihood of DILI wherein 1 = definite or > 95% likelihood of DILI, 2 = highly likely or 75–95% likelihood, 3 = probable or 50–74%, 4 = possible or 25–49%, and 5 = unlikely or < 25%. Each case was also assigned a Rousell- Uclaft Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) score and DILIN severity score of 1 to 5 (1= anicteric and 5 = fatal or needing transplant) (8, 14).

Liver histopathology

Available liver biopsy slides were reviewed by the DILIN hepatopathologist (D.E.K.) and the overall pattern of liver injury as well as individual histologic features were scored (15).

Genome wide association study (GWAS)

Genetic analysis focused on 39 European ancestry pediatric cases including 24 whom had been included in our previous genetic study (18 pediatric DILI cases genotyped with Illumina 1MDuo chip; 6 genotyped with Illumina HumanCoreExome chip) (9). See Supplemental text for more information.

RESULTS

Study population

Sixty pediatric cases were enrolled in the DILIN prospective and 9 cases in the retrospective study between September 2004 and February 2017. In causality assessment, 9 cases were adjudicated as only possible and 3 as unlikely DILI. Therefore, the current analysis was limited to the 57 cases (49 prospective and 8 retrospective) that were adjudicated as definite (n=14), highly likely (n=30) or probable (n=13) DILI.

The 57 patients had a median age of 14.3 years (range 1.7–17.9), 67% were female and 82% Caucasian (Table 1). The median duration of drug therapy prior to DILI onset (i.e. latency) was 55 days (range: 1 day to 7.6 years). Twenty-eight of the DILI cases were diagnosed while the patient was still receiving the implicated drug. In contrast, the median time between stopping the drug to DILI onset in the remaining 29 confirmed DILI cases was 1 day (range 1 to 42). There were 13 (22.8%) subjects who had a drug latency exceeding 12 months and the suspect agent in these cases included minocycline (6), atomoxetine (2), valproic acid (2), and 1 case each of fluoxetine, mercaptopurine, and methylphenidate DILI. 35% of the children self-reported a history of drug allergy that includes drug intolerance but none reported a prior episode of DILI.

Table 1:

Presenting features and outcomes in 57 Pediatric DILI cases

| Overall N=57 | Prospective DILI (N=49) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Self-limited (n=39) | Prospective Chronic (n=8) | p- value (Self-limited vs. Chronic) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 14.3 (1.7–17.9) | 14.6 (1.8–17.9) | 12.2 (1.7–17.9) | 0.462 |

| Female, n (%) | 38(66.7) | 26(66.7) | 6(75) | >0.99 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 47(83) | 31(80) | 8(100) | >0.99 |

| Black | 4(7) | 4(10) | 0 | |

| Other | 6(11) | 4(10) | 0 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.4 (12.8–37.3) | 21.6 (12.8–37.3) | 22.8 (13.2–30.3) | 0.49 |

| Medical conditions, n(%) | ||||

| Drug allergies ^^ | 20(35) | 12(31) | 3(38) | 0.70 |

| Neurologic | 13(23) | 7(18) | 1(13) | >0.99 |

| Pulmonary | 8(14) | 6(15) | 1(13) | >0.99 |

| Cardiac | 4(7) | 4(10) | 0 | >0.99 |

| Malignancy | 4(7) | 0 | 4(50) | <0.001 |

| Any alcohol use | 2(4) | 2(6) | 0 | >0.99 |

| Drug start to DILI onset (d) | 55 (1–2789) | 44 (2–840) | 131 (17–414) | 0.78 |

| Clinical signs and symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Jaundice | 30(53) | 20(51) | 5(63) | 0.71 |

| Abdominal pain | 24(42) | 17(44) | 3(38) | >0.99 |

| Fever | 21(37) | 15(39) | 3(38) | >0.99 |

| Nausea | 19(33) | 13(33) | 2(25) | >0.99 |

| Itching | 17(30) | 14(36) | 2(25) | 0.70 |

| Rash | 14(25) | 12(31) | 2(25) | >0.99 |

| DRESS | 7(13) | 6 (16) | 0 | xx |

| Stevens-Johnson | 2(4) | 1(3) | 1(13) | 0.32 |

|

At DILI onset | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 411 (33–4185) | 651 (73–4185) | 184 (33–411) | 0.002 |

| AST (IU/L) | 380 (26–3400) | 547 (47–3400) | 104 (40–376) | <0.001 |

| Alk P (IU/L) | 203 (62–1177) | 187 (62–573) | 152 (76–1177) | 0.68 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.3 (0.2–33.9) | 3.2 (0.2–33.9) | 4.8 (0.4–17.1) | 0.64 |

| INR | 1.2 (0.9–3.9) | 1.1 (0.9–3.9) | 1.1 (1.0–2.4) | 0.76 |

| Liver injury pattern, n (%) | ||||

| Hepatocellular | 40(82) | 30(88) | 4(67) | 0.11 |

| Mixed | 5(10) | 3(9) | 0 | |

| Cholestatic | 4(8) | 1(3) | 2(33) | |

| Median R value (range) | 19.2 (0.2– 71.8) | 25.2 (1.7–71.8) | 12.4 (0.2–26.2) | 0.12 |

| Eosinophil > 500/μL | 7(13) | 6(16) | 0 | 0.57 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1369 (369–7390) | 1379 (382–7390) | 1104 (369–1840) | 0.66 |

| ANA positive, n(%) | 20(44) | 15(44) | 2(29) | 0.68 |

| SMA positive, n(%) | 15(32) | 14(41) | 1(13) | 0.222 |

|

Peak lab values | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 732 (35–4185) | 969 (186–4185) | 297 (61–954) | 0.005 |

| AST (IU/L) | 482 (26–4715) | 727 (125–3641) | 172 (130–482) | 0.002 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 288 (98–1177) | 222 (106–888) | 290 (98–1177) | 0.55 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.0 (0.2–38.2) | 4.0 (0.3–38.2) | 12.4 (0.6–23.8) | 0.17 |

| INR | 1.2 (1.0–4.7) | 1.2 (1.0–3.9) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 0.15 |

| DILI onset to peak bilirubin* (days) | 4 (0–625) | 2 (0–36) | 7 (2–625) | 0.07 |

| DILI onset to peak ALT# (days) | 2 (0–415) | 2 (0–131) | 78 (7.0–415) | 0.03 |

| Corticosteroids (%) | 18 (31.6%) | 13 (33.3%) | 2 (25%) | 0.999 |

for cases with peak total bilirubin > 2.5 mg/dL Data reported as median (range)

for cases with peak ALT > 5xULN or > 5x baseline

per patient self-report which includes drug intolerance (not clinician determined) All data reported as n (%) or median (range)

DILI: drug-induced liver injury; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; Alk P: alkaline phosphatase; DRESS: Drug related eosinophilic systemic syndrome; INR: international normalized ratio; IgG: immunoglobulin G; ANA: antinuclear antibody; SMA: smooth muscle antibody

The most common presenting signs and symptoms were jaundice (53%), fever (37%), and rash (25%). At presentation, peripheral eosinophilia was noted in 13%, detectable anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) in 44% and smooth muscle antibody (SMA) in 32%. However, hypergammaglobulinemia with a serum immunoglobulin (IgG) > 1500 g/dL was present in only 12%. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen (n=54), anti-hepatitis C (n=48) and anti-hepatitis E (n=45) were negative in all cases with available test results.

Clinical outcomes

At DILI onset, 82% had a hepatocellular pattern of injury, 10% mixed and only 8% cholestatic. Initial median serum ALT was 411 U/L (range: 33–4185), Alk P 203 U/L (62–1177), and total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (0.2–33.9). The median peak ALT was 732 U/L (range: 35–4185), Alk P 288 U/L (98–1177) and total bilirubin 4.0 mg/dL (0.2–38.2). Of the 57 children, 37 (65%) were jaundiced (bilirubin ≥ 2.5 mg/dL), 36 (63%) were hospitalized or had a hospitalization prolonged due to DILI, and 3 (5%) underwent liver transplantation. The distribution of severity scores was mild 35%, moderate 18%, moderate-hospitalized 23%, severe 19%, and fatal/transplant 5%.

Implicated agents

There were 60 agents implicated as a primary cause of injury among the 57 cases (Table 2): 1 case involved two agents adjudicated equally as probable (mercaptopurine and thioguanine) and 1 case received an overall score of probable with 3 agents adjudicated equally as possible (fosphenytoin, phenobarbital, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). Antimicrobials were the most commonly implicated class of drugs (51%) followed by antiepileptics (21%), antineoplastic agents (9%) and psychotropic agents (9%). There was only one case with an implicated HDS product (“Hydroxycut: Ephedra-Free”).

Table 2.

Agents implicated in 57 pediatric DILI patients.

| Antimicrobial (29) | Antiepileptic(12) | Antineoplastic (5) | Psychotropic (5) |

| Minocycline (11) | Valproate (6) | Mercaptopurine (2) | Atomoxetine (3) |

| Azithromycin (4) | Lamotrigine (2) | Thioguanine (1) | Methylphenidate (1) |

| Isoniazid (4) | Carbamazepine (1) | Asparaginase (1) | Fluoxetine (1) |

| Trimethoprim/sulfa (4) | Ethosuximide (1) | Pegaspargase (1) | |

| Oxacillin (2) | Phenobarbital (1) | ||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate (1) | Phenytoin (1) | Other (7) | |

| Cefdinir (1) | Ethinyl estradiol (2) | ||

| Cefepime (1) | Hydroxycut (1) | ||

| Erythromycin (1) | Methyldopa (1) | ||

| Nicotinic acid (1) | |||

| Sulfasalazine (1) | |||

| * Multiple drugs (1) |

Case scored as probable overall; trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, phenobarbital, and fosphenytoin scored as possible

DILI: drug-induced liver injury

The 11 minocycline cases arose exclusively in adolescents being treated for facial acne (age: 15 to 17 years) of whom 73% were female. Drug latencies ranged from 1 month to 2.5 years but in 6 cases the latency exceeded 1 year. Four patients presented with arthralgias, and autoantibodies were detectable in 9 (9 with ANA and 4 with SMA as well). Ten children (91%) had a hepatocellular injury pattern while one was mixed, in whom the initial R ratio was 3.7 but later rose to 5.4. All 4 liver biopsies (obtained 22 to 220 days after DILI onset) showed a chronic hepatitic pattern of liver injury. Five children were treated with corticosteroids including 3 patients wherein steroids were given for 6 to 12 weeks with rapid normalization of liver biochemistries that remained normal after steroid discontinuation. In the remaining 2 patients, steroids were given for at least 2 and 7 months, respectively with normalization of liver biochemistries but neither patient had prolonged follow-up data available. At 6 and 12 months after DILI onset, serum enzyme levels remained elevated in two cases, but fell into the normal range in both when tested 2 years after onset.

The 6 valproate cases included 3 girls and 3 boys, ages 3 to 16 years with a latency to onset varying from 5 days to 7.6 years. One case presented with hyperammonemia and altered mental status, but normal serum aminotransferase levels. The remaining 5 cases presented with a combination of elevated aminotransferase levels and hyperammonemia, two of these with altered mental status. One valproate case in a 15-year-old male progressed to acute liver failure and required liver transplantation.

The 4 azithromycin cases occurred in 1 boy and 3 girls, ages 2 to 14 years with latencies ranging from 2 days to 2 months. Three cases presented with a cholestatic liver injury pattern and 3 underwent liver biopsy that showed an acute cholestatic pattern of injury with minimal inflammation in all. Regarding the 4 trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole cases, drug latencies ranged from 7 days to 5 months and 3 of the patients were receiving the drug for acne.

Liver histopathology

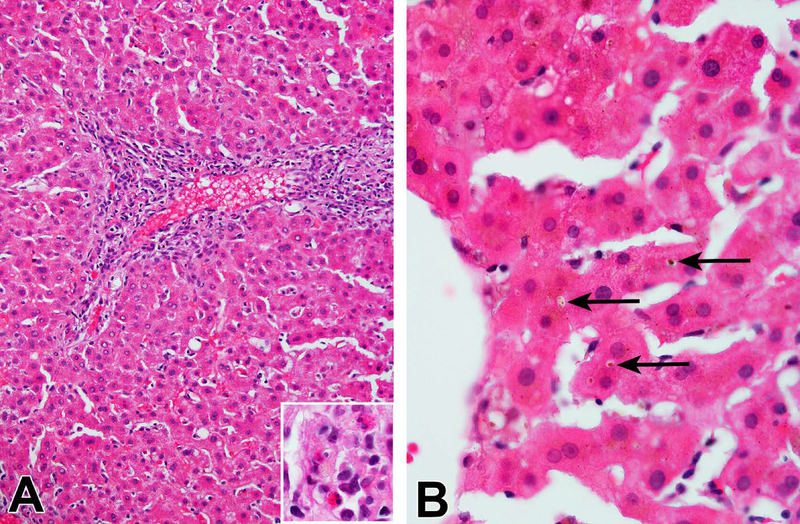

A total of 16 liver biopsies were available for review by DILIN’s hepatopathologist with 11 previously reported (12). Amongst the five new cases all showed histological changes consistent with the reported patterns of the implicated medications in adults (Table 3). Of note, none of the 16 cases showed cirrhosis although 3 had bridging fibrosis likely as a scarring reaction following bridging necrosis. Significant steatosis was also uncommon (2 of 16 cases), but none of the biopsies showed steatohepatitis as a main or secondary injury pattern. Figure 1 shows an example of carbamazepine induced DILI.

Table 3:

Liver Histopathology in pediatric DILI cases from 2011–17

| Drug | Age/gender | *Lab at DILI onset | Days from DILI onset | Inflammation severity | Plasma cells/Eosinophils | Pattern of Histology | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | 13/M | Hepatocellular | 1 | Marked | + / + | Marked acute hepatitis with mild cholestasis and bile duct injury | Resolved with prednisone and azathioprine during follow-up |

| Azithromycin | 2/F | Cholestatic | 331 | None | − / − | Acute (bland) cholestasis without inflammation, focal pseudoxanthomatous change | Chronic DILI with relapsing jaundice |

| Carbamazepine | 17/M | Hepatocellular | 7 | Mild | − /+ | Cholestatic hepatitis with mild inflammation and moderate cholestasis | Ursodiol and antihistamines for itching but DILI resolved by month 6 |

| Isoniazid | 17/F | Hepatocellular | 14 | Mild | + / − | Confluent necrosis involving 50% of the parenchyma with post-necrotic regenerative nodule formation and early bridging fibrosis | ALF leading to liver transplant at 14 days after DILI onset |

| Minocycline | 17/F | Cholestatic | 220 | Mild | + / − | Chronic hepatitis with mild inflammation and no fibrosis, no cholestasis | Chronic DILI resolved by month 21 of follow-up |

Figure 1-. Carbamazepine injury.

A 17-year-old Caucasian male presented with itching and ALT 157 IU/L, Alk P 155 IU/L and total bilirubin 19.9 mg/dl after receiving carbamazepine and perphenazine for 8 months for bipolar mood disorder. Liver biopsy obtained 7 days after DILI onset showed cholestatic hepatitis with mild inflammation and moderate cholestasis. His symptoms slowly resolved and labs normalized by month 6 of follow-up. A). Mild portal and lobular inflammation with scattered eosinophils among the lymphocytes and macrophages (inset) (H&E, 200x). B). Zone 3 cholestasis with small bile plugs in canaliculi (H&E, 600x)

Chronic DILI

Among 46 children with follow up of at least 6 months after onset, 8 (17%) had persistently abnormal laboratory values. Children who developed chronic liver injury had significantly lower initial and peak serum AST and ALT levels compared to those with self-limited DILI (Table 1). Chronic liver injury attributed to minocycline arose in two adolescent females with facial acne (12). A 17 year old female underwent a liver biopsy 7 months after onset demonstrating chronic hepatitis with periportal and lobular inflammation (Table 3). However, her serum aminotransferases spontaneously improved without treatment and remained normal at 33 months of follow-up. See Supplemental text for more information.

Antineoplastic agents were responsible for 4 of the cases of chronic DILI in children who were being treated for leukemia (n=3) or lymphoma. The responsible agents were either thiopurines (thioguanine or mercaptopurine) or asparaginase/pegaspargase. In most instances there was rapid resolution of jaundice after the implicated agent(s) were stopped. Nevertheless, minor elevations in serum aminotransferase levels were found in follow up, although in many instances other antineoplastic agents were being administered and it was unclear whether the liver injury was due to a long-term effect of the initially implicated agent or to a low-grade injury caused by the subsequent antineoplastic regimen. For more information regarding the 3 patients undergoing liver transplantation see Supplemental Text.

Genome wide association study

A GWAS was conducted on 39 European ancestry pediatric DILI patients. Due to the small sample size, the analysis of variants was focused on genes previously reported to be involved in cholestasis during childhood, including but not limited to those on the Emory Cholestasis Panel (Table S1) (19, 20). A review of the 7,756 variants genotyped or imputed in or near these genes as well as HLA types failed to identify any SNPs that were significantly over-represented in children with DILI compared to the 10,397 European ethnicity population controls.

Discussion

This series of pediatric DILI cases enrolled into the ongoing DILIN prospective and retrospective registries provides a general overview of the implicated agents, clinical features and consequences of DILI in the pediatric population of the United States during the last 13 years. This study is an update on the initial description of pediatric DILI published in 2011 (12). A wide variety of agents can cause hepatotoxicity in children but antimicrobials (51%) and anti-epileptics (21%) were the most commonly implicated classes of drugs (Table 2). Of note, antibiotics were also the most common cause of DILI amongst adults but HDS products, analgesics, and lipid-lowering agents are also frequent causes in adults but rare or absent in children (22). These differences appear to be related to the types and classes of drugs that are more commonly used in children. In this regard, the antibiotics most frequently implicated in DILIN in adults that are uncommon in children include amoxicillin/clavulanate, nitrofurantoin and the fluoroquinolones. Amoxicillin/clavulanate stands out as a drug that is commonly used in children but accounted for only one case in this series. Interestingly, the clinical presentation was hepatocellular (ALT 2396 U/L, Alk P 565 U/L, R= 13.7) which is different from what occurs most commonly in adults, although hepatocellular injury has been reported to be more frequent in younger adults with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid liver injury (23).

In most regards, the clinical features of DILI in children resembled that in adults with a few exceptions. Pediatric DILI can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality as also reported in adults (22, 24). In particular, the majority of pediatric DILI cases had severity scores reflecting significant complications including the need for hospitalization (63%) and severe liver dysfunction (24%) with liver transplantation required in 5%. While most children recovered from DILI, 17% developed evidence of chronic liver injury at 6 months after DILI onset which aligns with the 17% incidence in adult DILIN cases (22).

Another notable finding is that the pattern of liver injury among children is more frequently hepatocellular at DILI onset compared to adults (82% vs 54%) (22). One possible explanation for this difference is that the most common causes of liver injury in children were agents that typically cause hepatocellular injury such as minocycline, valproate, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and isoniazid. Furthermore, there may be an artifactual skewing toward higher R ratios among children because of the high upper limits of normal for Alk P in children, due largely to higher levels of bone-derived Alk P associated with growth (Supplementary Figure 2). Because R is a ratio, the higher ULN makes similar increases in liver-derived Alk P of less influence than with lower ULN as used in adults. A more accurate R ratio might employ measurements of liver specific Alk P or use GGT levels instead.

Minocycline was the most commonly implicated drug (Table 2). Interestingly, more than half of the minocycline cases were associated with a latency exceeding 1 year of continuous daily dosing as reported in adults (11). Other distinctive features include a high frequency of autoimmunity such as positive serum autoantibodies in 81%, arthralgias in 36%, and a chronic anicteric, hepatocellular liver injury pattern in the 4 patients with a liver biopsy. Fortunately, most cases resolved with withdrawal of minocycline but 36% were treated with a short course of corticosteroids. Although there are no consensus guidelines regarding bloodwork monitoring for minocycline therapy, the American Association of Pediatrics recommends careful monitoring for adverse effects in all children receiving oral antimicrobials for acne (25). Based upon our data, routine monitoring of liver biochemistries every 3–4 months in any patient receiving chronic minocycline is advisable. In addition, clinicians should watch for symptoms of arthralgias, rash or fatigue at any time during treatment.

Anti-epileptics were the second most common category of implicated agents with the majority of cases attributed to valproic acid. Notable features of valproate DILI included a wide range of affected ages (3–15 years) and drug latencies that varied from very short to quite long (5 days to 8 years). The clinical presentations also varied from isolated hyperammonemia with altered mental status to an acute hepatitis with rapidly progressive liver failure (26). There have been at least 156 pediatric deaths attributed to valproic acid hepatotoxicity through 2012 and children less than 6 years of age, and those receiving multiple anticonvulsants appeared to be at the greatest risk (27). As we found in in one of our cases, others have demonstrated that children with mitochondrial disorders, such as POLG mutations, are at higher risk of valproic acid-induced hepatotoxicity (21, 28, 29). However, POLG mutations were not identified in any of the remaining 5 cases.

The third most commonly implicated class of agents in children were antineoplastic drugs. Amongst our 5 cases, 4 developed chronic DILI during follow-up. All of the cases presented with elevated serum aminotransferase levels and jaundice but the jaundice resolved quickly with discontinuation of the offending drug. Importantly, all of the patients were able to continue chemotherapy with eventual normalization of transaminases and successful treatment of their underlying malignancy. There is a paucity of literature regarding pediatric chemotherapy-induced DILI but it is generally regarded as common and mild in severity. Nonetheless, a recent Cochrane review reported a high estimated incidence of chronic liver injury resulting from chemotherapy in long-term survivors of childhood cancer ranging from 7.9–44.8% (6).

This study represents the largest collection of histopathology attributed to DILI amongst children. All 4 minocycline cases showed a chronic hepatitic histopathology while all 3 azithromycin cases were associated with an acute cholestatic pattern and minimal inflammation. Severe fibrosis was rare with bridging fibrosis noted only in two cases (atomoxetine and isoniazid) and steatosis was also remarkably unusual compared to adults (15).

This study also provided a unique opportunity to examine the role of host genetic polymorphisms in DILI susceptibility and outcomes. When grouping the 39 Caucasian pediatric cases together, a significant overrepresentation was not identified in any of the 7,756 common SNPs that are near genes associated with underlying congenital pediatric liver disease. The lack of a significant association may be due to the small sample size of our population that included 27 different individual agents. In support of this, the first analysis of the adult DILIN cohort failed to demonstrate a common SNP in 750 total cases while a more recent analysis including over 1500 total DILI cases identified several HLA alleles associated with DILI susceptibility (9). Lastly, the single patient with azithromycin DILI who has experienced repeated, discrete episodes of intense pruritus and jaundice, raises suspicion for BRIC (30, 31). Because she had persistently low levels of serum GGT, PCR-based sequencing to evaluate for mutations in ATP8B1 and ABCB11 was performed but negative. In addition, GWA testing for candidate genes known to be associated with low-GGT progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis syndromes (including AKR1D1, BAAT, CYP7B1, HSD3B7, TJP2, VPS33B, and MYO5B) were also undertaken but negative. Since our GWAS did not provide a thorough assessment of all variants in these candidate genes, additional studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing may prove worthwhile.

Strengths of our study include the prospective collection of cases in a protocol driven manner at multiple medical centers, which improves the generalizability of our findings. Other strengths include the exclusion of all other known causes of acute and chronic liver injury in our prospective cases along with their prolonged follow-up. Furthermore, a moderate number of liver biopsies were available to review that further strengthened our phenotypic characterization. Limitations include the fact that our study is not population-based and therefore the data does not establish the true overall incidence of DILI in the pediatric population. Furthermore, our study is subject to referral bias since children with more severe liver disease were more likely to be referred a DILIN site. Although DILI is rare in children, the substantial morbidity and mortality highlighted in the current series demonstrates the need for ongoing multicenter studies of its etiopathogenesis to improve opportunities for future interventions and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Lab trends of 13-year-old female with drug-induced liver injury (DILI) secondary to mercaptopurine and thioguanine. Arrow indicates time point of normalization of all labs at 17 months post DILI. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; Alk P = alkaline phosphatase; TB = total bilirubin; ULN = upper limit of normal; solid line represents ALT lab trend; hashed line represents total bilirubin lab trend; dotted line represents Alk P lab trend. Each lab value is plotted as ratio of lab upper limit of normal.

Supplementary Figure 2. Reference value distributions for alkaline phosphatase based on data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey (top panel) or the CALIPER cohort of healthy community children and adolescents (bottom panel). Reprinted from Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistries and Molecular Diagnostics, 6th Edition with permission from Elselvier (32–34).

1. WHAT IS KNOWN?

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among adults.

There is limited published data regarding the features of pediatric DILI.

2. WHAT IS NEW?

Antimicrobials (51%) and anti-epileptic agents (21%) are most frequently implicated in pediatric DILI, and minocycline and valproate are the most common individual agents.

Although children are more likely than adults to present with acute hepatocellular injury, the liver histopathology in biopsied children is generally similar to that reported in adults.

DILI can lead to both acute liver failure necessitating liver transplant (5%) and chronic DILI (17%) in children as has been reported in adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DILIN Clinical Sites:

Indiana University-Purdue: Naga Chalasani, MD, PI; Marwan S. Ghabril, MD, Sub-I; Marwan Ghabril, MD, Sub-I; Raj Vuppalanchi, MD, Sub-I; Study Coord; Wendy Morlan, RN, Study Coord;

University of Michigan-Ann Arbor: Robert J. Fontana, MD, PI; Hari Conjeevaram, MD, Sub-I; Frank DiPaola, MD, Sub-I; [Dora Siettas, Study Coord; Ben Johnson, Study Coord];

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill: Paul Watkins, MD, PI; Jama Darling, MD, Sub-I; Michael Fried, Sub-I; Paul H. Hayashi, MD, Sub-I; Steven Lichtman, MD, Sub-I; Steven Zacks, MD, MPH, Sub-I; [Tracy Russell, CCRP, Study Coord];

Satellite Sites:

Asheville: William Harlan, MD, PI; [Tracy Russell, CCRP, Study Coord];

Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center: Herbert Bonkovsky, MD, PI; Pradeep Yarra, MD, Sub-I; [Denise Faust, Study Coord];

University of Southern California: Andrew Stolz, MD, PI; Neil Kaplowitz, MD, Sub-I; John Donovan, MD, Sub-I; [Susan Milstein, RN, BSN, Study Coord];

Satellite Sites:

University of California-Los Angeles (Pfleger Liver Institute): Francisco A. Durazo, MD, PI; [Yolanda Melgoza, Study Coord; Val Peacock, RN, BSN, Co-Coord]

Albert Einstein Medical Center: Victor J. Navarro, MD, PI; Simona Rossi, MD, Sub-I; [Maricruz Vega, MPH, Study Coord; Manisha Verma, MD, MPH, Study Coord]

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai: Joseph Odin, MD, PhD, PI; Jawad Ahmad, MD, PI; Nancy Bach, Sub-I; Meena Bansal, MD, Sub-I; Charissa Chang, MD, Sub-I; Douglas Dieterich, MD, Sub-I; Priya Grewal, MD, Sub-I; Lawrence Liu, MD, Sub-I; Thomas Schiano, MD, Sub-I; [Monica Taveras, Study Coord]

National Institutes of Health Clinical Center: Christopher Koh, MD, PI; [Beverly Niles, Study Coord]

DILIN Data Coordinating Center at Duke Clinical Research Institute: Huiman X. Barnhart, PhD, PI; Katherine Galan, RN, Project Lead; Theresa O’Reilly, Lead CRA; Elizabeth Mocka, CRA; Olivia Pearce, CTA; Michelle McClanahan-Crowder, Data Management; Coleen Crespo-Elliott, Data Management; Hoss Rostami, Data Management; Qinghong Yang, Programmer-Statistics; Jiezhun (Sherry) Gu, PhD, Statistician; Tuan Chau, Lead Safety Associate; Liz Cirulli-Rogers, PhD, Pharmacogenetics statistician

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): José Serrano, MD, PhD, Project Scientist; Sherry R. Hall, MS, Clinical Trials Specialist; Jay Hoofnagle, MD, Scientific Advisor; Averell H. Sherker, MD, FRCP(C), Program Official.

National Cancer Institute: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD, Hepatopathologist.

Additional Staff

Tuan Chau, Duke Clinical Research Institute; Coleen Crespo-Elliott, Duke Clinical Research Institute; Katherine Galan, Duke Clinical Research Institute; Michelle McClanahan-Crowder, Duke Clinical Research Institute; Hoss Rostami, Duke Clinical Research Institute; Rebecca J. Torrance, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Rebekah Van Raaphorst, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Qinghong Yang, Duke Clinical Research Institute;

Sources of Funding:

The DILIN Network is structured as a U01 cooperative agreement with funds provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) under grants: U01-DK065176 (Duke), U01-DK065201 (UNC), U01-DK065184 (Michigan), U01-DK065211 (Indiana), U01DK065193 (UConn), U01-DK065238 (UCSF/CPMC), U01-DK083023 (UTSW), U01-DK083027 (TJH/UPenn), U01-DK082992 (Mayo), U01-DK083020 (USC). Additional support is provided by CTSA grants: UL1 RR025761 (Indiana), UL1TR000083 (UNC), UL1 RR024134 (UPenn), UL1 RR024986 (Michigan), UL1 RR024982 (UTSW), UL1 RR024150 (Mayo) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- ALF

Acute liver failure

- Alk P

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- ANA

Anti-nuclear antibody

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BRIC

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis

- DILI

Drug induced liver injury

- DILIN

Drug induced liver injury network

- DRESS

Drug related eosinophilic systemic syndrome

- GGT

γ glutamyl transferase

- GWA

Genome wide association

- HDS

Herbal and dietary supplement

- HLA

Human Leukocyte antigen

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- INR

International normalized ratio

- POLG

Polymerase γ gene

- RUCAM

Rousell- Uclaf Causality Assessment Method

- SMA

Smooth muscle antibody

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Fontana has received research support from Gilead, Bristol-Myer Squibb, and Abbvie and has consulted for Alynam Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Molleston has received research support (not related to DILI) from Gilead, Abbvie, and Shire.

Drs. DiPaola, Hoofnagle, Kleiner, Barnhart, and Gu have no potential conflicts.

Dr. Chalasani consults for several pharmaceutical companies but has no reported conflicts for this manuscript.

Dr. Cirulli is currently an employee of Human Longevity but was at Duke University when studies were completed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sgro C, Clinard F, Ouazir K, et al. Incidence of drug-induced hepatic injuries: a French population-based study. Hepatology 2002;36:451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjornsson ES, Bergmann OM, Bjornsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1419–25, 1425, e1–3; quiz e19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Health, United States, 2016. July 18th, 2017. [cited 2017 July 31st, 2017]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2016.htm#079

- 4.Alonso RHSaEM. Acute Liver Failure in Children In: Frederick Suchy M, Ronald Sokol, and Balistreri William, editor. Liver Disease in Children. 4 ed: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson SC, Smith S, Weissman SJ, et al. Adverse Events in Pediatric Patients Receiving Long-Term Outpatient Antimicrobials. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2015;4:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulder RL, van Dalen EC, Van den Hof M, et al. Hepatic late adverse effects after antineoplastic treatment for childhood cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD008205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green DM, Wang M, Krasin MJ, et al. Serum ALT elevations in survivors of childhood cancer. A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana RJ, Watkins PB, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) prospective study: rationale, design and conduct. Drug Saf 2009;32:55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicoletti P, Aithal GP, Bjornsson ES, et al. Association of Liver Injury From Specific Drugs, or Groups of Drugs, With Polymorphisms in HLA and Other Genes in a Genome-Wide Association Study. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1078–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucena MI, Molokhia M, Shen Y, et al. Susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanate-induced liver injury is influenced by multiple HLA class I and II alleles. Gastroenterology 2011;141:338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban TJ, Nicoletti P, Chalasani N, et al. Minocycline hepatotoxicity: Clinical characterization and identification of HLA-B *35:02 as a risk factor. J Hepatol 2017;67:137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molleston JP, Fontana RJ, Lopez MJ, et al. Characteristics of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury in children: results from the DILIN prospective study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;53:182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockey DC, Seeff LB, Rochon J, et al. Causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury using a structured expert opinion process: comparison to the Roussel-Uclaf causality assessment method. Hepatology 2010;51:2117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs--I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology 2014;59:661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das S, Forer L, Schonherr S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 2016;48:1284–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet 2016;48:1279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emory Genetics Laboratory. [cited; Available from: <http://www.egl-eurofins.com/documents/NeonatalCholestasis.pdf>

- 20.Gonzales E, Taylor SA, Davit-Spraul A, et al. MYO5B mutations cause cholestasis with normal serum gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in children without microvillous inclusion disease. Hepatology 2017;65:164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart JD, Horvath R, Baruffini E, et al. Polymerase gamma gene POLG determines the risk of sodium valproate-induced liver toxicity. Hepatology 2010;52:1791–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, et al. Features and Outcomes of 899 Patients With Drug-Induced Liver Injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1340–52 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.deLemos AS, Ghabril M, Rockey DC, et al. Amoxicillin-clavulanate induced liver injury. Dig Dis Sci 2016: 61: 2406–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucena MI, Andrade RJ, Kaplowitz N, et al. Phenotypic characterization of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: the influence of age and sex. Hepatology 2009;49:2001–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichenfield LF, Krakowski AC, Piggott C, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acne. Pediatrics 2013;131 Suppl 3:S163–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Adverse drug reactions induced by valproic acid. Clin Biochem 2013;46:1323–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Star K, Edwards IR, Choonara I. Valproic acid and fatalities in children: a review of individual case safety reports in VigiBase. PLoS One 2014;9:e108970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price KE, Pearce RE, Garg UC, et al. Effects of valproic acid on organic acid metabolism in children: a metabolic profiling study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89:867–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saneto RP, Lee IC, Koenig MK, et al. POLG DNA testing as an emerging standard of care before instituting valproic acid therapy for pediatric seizure disorders. Seizure 2010;19:140–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacquemin E Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36 Suppl 1:S26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davit-Spraul A, Fabre M, Branchereau S, et al. ATP8B1 and ABCB11 analysis in 62 children with normal gamma-glutamyl transferase progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC): phenotypic differences between PFIC1 and PFIC2 and natural history. Hepatology 2010;51:1645–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adeli KCF, and Nieuwesteeg M. Reference Information for the Clinical Laboratory In: Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics. 6th ed: Elselvier; 2018. p. 1745–1818. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adeli K, Higgins V, Nieuwesteeg M, et al. Complex reference values for endocrine and special chemistry biomarkers across pediatric, adult, and geriatric ages: establishment of robust pediatric and adult reference intervals on the basis of the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Clin Chem 2015;61:1063–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colantonio DA, Kyriakopoulou L, Chan MK, et al. Closing the gaps in pediatric laboratory reference intervals: a CALIPER database of 40 biochemical markers in a healthy and multiethnic population of children. Clin Chem 2012;58:854–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Lab trends of 13-year-old female with drug-induced liver injury (DILI) secondary to mercaptopurine and thioguanine. Arrow indicates time point of normalization of all labs at 17 months post DILI. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; Alk P = alkaline phosphatase; TB = total bilirubin; ULN = upper limit of normal; solid line represents ALT lab trend; hashed line represents total bilirubin lab trend; dotted line represents Alk P lab trend. Each lab value is plotted as ratio of lab upper limit of normal.

Supplementary Figure 2. Reference value distributions for alkaline phosphatase based on data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey (top panel) or the CALIPER cohort of healthy community children and adolescents (bottom panel). Reprinted from Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistries and Molecular Diagnostics, 6th Edition with permission from Elselvier (32–34).