Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate gastrointestinal symptoms and continence in the context of Phelan-McDermid Syndrome (PMS).

Study design:

A prospective evaluation of children with PMS (n=17) at the National Institutes of Health.

Results:

Parent-reported history of symptoms were common: constipation (65%), reflux (59%), choking/gagging (41%), and more than half received gastrointestinal specialty care. No aspiration was noted in 11/11 participants who completed modified barium swallows. Four participants met criteria for functional constipation, 2 of whom had abnormal colonic transit studies. Stool incontinence was highly prevalent (13/17) with non-retentive features present in 12/17. Participants who were continent had significantly smaller genetic deletions (p=0.01) and higher nonverbal mental age (p=0.03) compared to incontinent participants.

Conclusion:

Incontinence is common in PMS and associated with intellectual functioning and gene deletion size. Management strategies may differ based on the presence of non-retentive fecal incontinence, functional constipation, and degree of intellectual disability for children with PMS.

Keywords: constipation, incontinence, intellectual disability, SHANK3

Introduction

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome (PMS) is a rare condition defined primarily by copy number losses or rearrangements on chromosome 22q13.3, most commonly involving SHANK3 (1). Prevalence is unknown but currently there are nearly 2,000 affected individuals worldwide registered with the Phelan McDermid Syndrome Foundation (2). PMS is associated with severe cognitive impairments leading to Intellectual Disability (ID), symptoms of autism, hypotonia and motor delays, and absent or delayed speech (1). SHANK3 is responsible for synaptic functioning and deletions or mutations of this gene are thought to be a key factor for the developmental delay and characteristic behaviors in the PMS population (1, 3). Other medical conditions in patients with PMS include seizure disorders, endocrinopathies, cardiac malformations, renal disease, and gastrointestinal (GI) conditions (4, 5). Deletion sizes and specific mutations differ significantly within the population and are hypothesized to be responsible for the variability in clinical characteristics and management of patients (6).

GI problems, in particular constipation, incontinence and reflux, are commonly reported in PMS and frequently trigger consultation with specialists (4, 7). Important relationships between ID and GI dysfunction have previously been observed in individuals with various genetic disorders (8-11). Von Wendt et al. (9) and von Gontard (8) separately described an inverse relationship between IQ and continence, and both authors have used an IQ < 70 as the most significant risk factor for urinary and fecal incontinence. Rett syndrome and Fragile X are two genetic conditions characterized by ID that are very commonly associated with incontinence, with 98% of children with Rett syndrome and 71% of children with Fragile X reporting incontinence (8). Constipation also plays a significant role in these populations. Unfortunately, other medical and behavioral problems tend to take precedence over voiding and stooling dysfunction, and opportunities for behavioral or medical intervention are often missed (12, 13).

Bowel and bladder control are important markers for quality of life for families and patients with PMS. The aim of this study was to report the frequency of GI symptoms in a cohort of children with PMS and to evaluate the relationship between continence, intellectual disability, and gene deletion size.

Methods

Participants

Seventeen children/adolescents with PMS participated in a natural history study at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland (NCT02461420). Each participant underwent a standardized GI assessment between January 2014 and January 2018. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained for participation.

Gastrointestinal Consult

A standardized GI symptom form was administered to each family by a Pediatric Gastroenterologist (CH). Caregivers answered whether their child had ever experienced a range of GI symptoms and when present, more detailed questions were directed at severity, frequency and treatments. Parents also answered detailed questions related to the history of toilet training and continence of urine and stool. Rome IV criteria were used for the definitions of functional constipation and cyclic vomiting (14). Continence was defined as the ability to use the toilet for urination and defecation 100% of the time. Primary incontinence was defined as participants who never achieved a period of continence. The use of GI specialty care, imaging, labs, procedures, and medications were also reviewed when available.

Radiologic Studies

Each participant was offered an opportunity to complete a colonic transit study and modified barium swallow as part of the research protocol. Thirteen participants completed a colonic transit study using the simplified sitzmarks method and were instructed to withhold all laxatives during the duration of this study. Each participant ingested one capsule with 24 markers, and had an X-ray performed five days following marker ingestion (15, 16). Eleven patients completed a modified barium swallow study to evaluate swallowing function and potential aspiration.

Genetic Testing

Genetic mutation or deletion size was confirmed through array comparative genomic hybridization and by fluorescence in situ hybridization, as outlined by Khan et al. (17).

Neurocognitive Testing

Neurodevelopmental testing was completed by psychologists using one of the following tests: the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (18), the Leiter International Performance Scale, Revised (19), or the Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition (20). Nonverbal Mental Ability (NVMA) and Full Scale IQ or developmental quotient (FSIQ/DQ) were determined from this battery (17).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS JMP Version 13.2.0. Summary statistics are presented as median and interquartile range. Comparisons between subgroups were made using non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests or chi-square statistics where appropriate.

Results

The median age of the cohort was 11 years and 8/17 (46%) of the cohort was male, 15/17 (88%) were Caucasian (Table 1). The majority of the cohort (14/18) had a normal body mass index, while one was less than the 3rd percentile and two were greater than the 90th percentile.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Assessment of Individuals with Phelan McDermid Syndrome (n=17)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 11 (5.5, 14.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 8 (47%) |

| Female, n (%) | 9 (53%) |

| White/not Hispanic, n (%) | 15 (88%) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 1 (6%) |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (6%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 17.5 (15.6, 19.6) |

| BMI ≤ 3%ile, n (%) | 1 (6%) |

| BMI 4-10%ile, n (%) | 4 (24%) |

| BMI 11-89%ile, n (%) | 10 (59%) |

| BMI ≥ 90%ile, n (%) | 2 (12%) |

| Deletion Size, Mb† | 4.065 (0.0641, 6.444) |

| NVMA, months | 17 (13, 24) |

| FSIQ/FSDQ | 11.9 (6.7, 27.9) |

| Primary urinary incontinence, n (%) | 11 (65%) |

| Primary fecal incontinence, n (%) | 12 (71%) |

Values represent median (interquartile range) unless otherwise noted

Excluding the two patients with genetic mutations rather than deletions

NVMA – Non-Verbal Mental Age

FSIQ/FSDQ – Full Scale Intelligence Quotient/Full Scale Developmental Quotient

Genetic Characteristics.

All 17 participants had either a deletion (n=15) or heterozygous mutation (n=2) in the SHANK3 gene. Deletion sizes ranged from 0.055 Mb to 7.7 Mb.

Neurocognitive Testing

Twelve participants (71%) were classified as non-verbal, while five (29%) had either single word or phrase speech. The median NVMA was 17 months, despite the median chronological age of 11 years. The median FSIQ/DQ was 11.9. ID classifications included 76% with profound ID, while 6% had severe ID, 12% had moderate ID and 6% had mild ID. Eight participants (47%) carried a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and other behavioral problems were prevalent (e.g. pica, hyperactivity).

Gastrointestinal Evaluation

Lifetime prevalence of parent-reported GI symptoms was very common in this cohort, including constipation (11/17, 65%), reflux (10/17, 59%), abdominal pain (7/17, 41%), choking and gagging (7/17, 41%) (Table 2). Vomiting was less common (5/17, 29%) and no patient met criteria for cyclic vomiting. Further, 53% (9/17) had seen a GI specialist at least once, 76% (13/17) had a history of taking a medication for GI symptoms, and 53% (9/17) were taking one of these medications at the time of the evaluation. Three participants had undergone esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), two of which were conducted for the retrieval of a foreign body that had been ingested in relation to pica.

Table 2.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Medication Use History

| Symptom/Medication | Parent ever reporting symptom/use |

Currently reporting symptom/use |

|---|---|---|

| Choking, Gagging (%) | 7/17 (41%) | 5/17 (29%) |

| Reflux (%) | 10/17 (59%) | 4/17 (24%) |

| PPI† (%) | 8/17 (47%) | 4/17 (24%) |

| H2RA† (%) | 3/17 (18%) | 0/17 (0%) |

| Vomiting (%) | 5/17 (29%) | 1/17 (6%) |

| Gas, bloating (%) | 5/17 (31%) | 4/17 (24%) |

| Abdominal Pain (%) | 7/17 (41%) | 2/17 (12%) |

| Constipation (%) | 11/17 (65%) | 6/17 (35%) |

| Osmotic Laxative† (%) | 7/17 (41%) | 2/17 (12%) |

| Stimulant† (%) | 3/17 (18%) | 1/17 (6%) |

| Suppository/Enema† (%) | 4/17 (24%) | 2/17 (12%) |

| Diarrhea (%) | 5/17 (29%) | 3/17 (18%) |

PPI – proton pump inhibitor

H2RA – histamine 2 receptor antagonist

Parent reported clinical benefit with medication therapy in all cases

Incontinence was the most prevalent problem reported. Current prevalence of urinary incontinence was 12/17 (71%) with primary incontinence of urine in 11/17 (65%). For stooling behaviors, current prevalence of stool incontinence was 13/17 (76%), with primary incontinence of stool in 12/17 (71%). For those individuals that were successfully toilet trained, the average age of toilet training completion was 5 years (range 4-9 years). Families of nine of the 13 participants reported continued efforts to toilet train, regardless of age or developmental stage.

Functional constipation using Rome IV criteria was diagnosed in 4/17 participants. Three of these 4 were currently using a bowel regimen and incontinent of stool, one of whom also had a past history of retentive posturing. No other family reported similar behaviors.

Radiologic Studies

Two of the 13 participants who completed a colonic transit study had abnormal retention of markers (17 and 20 markers respectively in the rectosigmoid at day five). Finally, one subject who had a normal colonic transit study opted to continue their usual laxative regimen (2-3 sennosides 8.6 mg tablets per day), making it difficult to interpret.

Of the 11 participants who completed a modified barium swallow study (MBS), all were without evidence of aspiration. While 7/11 exhibited immature mastication, only 3 of the 7 with that finding reported a history of choking and gagging. In the 4 cases with normal mastication on MBS, there was no reported history of choking or gagging.

Continence, deletion size, and neurocognitive functioning

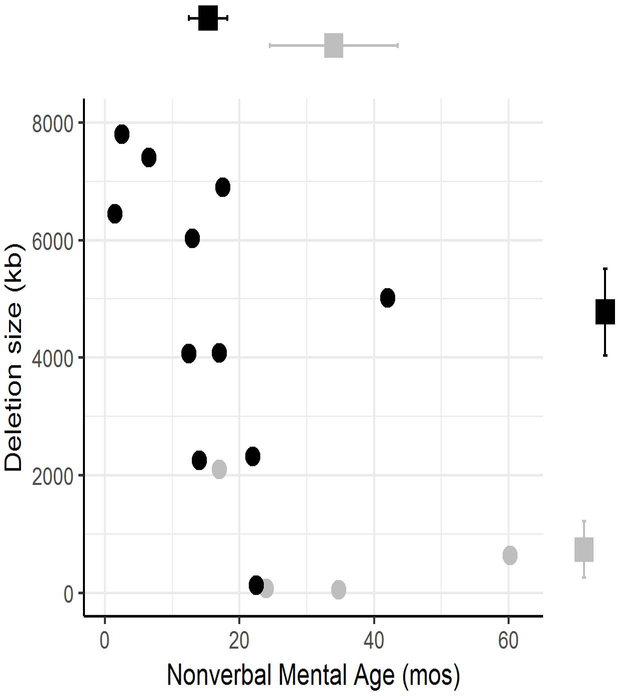

Figure 1 shows that participants who were continent of urine and stool at the time of evaluation (n=4) had a significantly smaller deletion size than those with incontinence of urine and stool (mean: 717 kb vs. 4767 kb, p=0.01). Participants who were continent also had significantly higher mean NVMA (34 months vs. 15 months, p=0.03, Figure 1) and higher estimated mean FSIQ/DQ (41.4 vs. 10.8, p=0.01). Three of the four continent participants had mild or moderate ID, whereas all but one of the incontinent participants had profound ID (Pearson’s chi-square=11.9, p=0.008).

Figure 1.

Continent subjects (light grey circles) and incontinent subjects (black circles) plotted by gene deletion size in Mb and Non-Verbal Mental Age (NVMA). Mean values differed between groups for both deletion size (p=0.01) and NVMA (p=0.03) and are represented by squares with error bars on the corresponding axes. .

Discussion

Parent-reported gastrointestinal symptoms are common in PMS with high rates of specialty care utilization. In this cohort incontinence was observed in 76% of participants. Bowel and bladder control are important markers for quality of life for families and individuals with disabilities. A developmental age of at least 4 years is needed to accurately apply the Rome IV definition of non-retentive fecal incontinence, however withholding behavior and evidence of fecal retention was not common, suggesting the nature of incontinence is predominantly non-retentive in PMS (14). Most families expressed that toilet training remained a focus in their household. It is possible that early introduction of behavioral modification for those with non-retentive patterns may be key to improved quality of life for PMS patients and their families. Previous studies have shown success with behavioral modifications such as urine alarms or parent training modules for children with Intellectual Disability, especially when tried early (12, 13). In addition, the subset of patients with functional constipation may benefit from more regular bowel regimens.

Neurocognitive testing and genetic characteristics can also be helpful in stratifying children by likelihood of reaching continence. The youth who were continent had a smaller gene deletion size and a higher non-verbal mental age. Two prior studies of PMS described high rates of Intellectual Disability and incontinence (4, 7). A larger cohort of 201 individuals with PMS were surveyed by Sarasua et al. and reported similar findings to our study with 24% of children achieving continence, which increased in an age dependent manner, with 60% of the 18-64 year olds achieving continence (4). The authors also reported that speech ability was inversely correlated with gene deletion size. Our study replicates these findings and builds on the relationship between incontinence with FSIQ and NVMA.

This prospective natural history study additionally describes the high prevalence and nature of gastrointestinal symptoms in this population. Over half of the patients suffered from constipation and reflux, and more than 75% required medications to control their GI symptoms. Despite these complaints, the majority of patients had normal colonic transit studies and modified barium swallow studies. It is important to have a high index of suspicion for GI conditions in this population, as children with PMS are frequently described as having an increased tolerance for pain. This study supports the current practice guideline for PMS management that recommends subspecialist evaluation by a gastroenterologist, especially for changes in appetite or behavior (5).

The limitations of this study include the small sample size. Additionally, the families who chose to participate in this natural history study and to complete radiologic studies may not be representative of the general population of patients with PMS, which can result in selection bias. Finally, parent report of symptoms and medical history can introduce recall bias, and outside records were not always available for confirmation.

The strengths of this study come from the prospective and comprehensive nature of the patient evaluation. The standardized consultation with a GI specialist allowed for more nuanced discussion of GI symptoms and toilet training behaviors, and resulted in more appropriate diagnostic categorization. The availability of imaging studies also aided in the diagnostic process. Previous studies performed with larger populations relied heavily on caregiver questionnaires (4) or medical record review (7), which can be subject to recall bias and misinterpretation.

In conclusion, GI complaints are common in PMS, from constipation to feeding difficulties. Incontinence is one of the most prevalent challenges facing patients and their families and can lead to stressful experiences with toilet training. It is possible that the recognition of non-retentive fecal incontinence and functional constipation will help providers recommend more appropriate individualized therapies. Further, consideration of genetic deletion size and intellectual ability may also help set realistic expectations for reaching continence.

Supplementary Material

What is known?

Gastrointestinal complaints are highly prevalent in children with neurodevelopmental disorders, especially incontinence.

Children with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome frequently suffer from constipation, incontinence and reflux.

What is new?

More than half of patients with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome seek care by a gastrointestinal specialist.

Intellectual Disability and gene deletion size are closely related to incontinence.

Constipation and gagging are among the most common symptoms, but colonic transit studies and modified swallow studies are largely normal.

Careful assessment to identify non-retentive fecal incontinence and functional constipation may help providers recommend more appropriate individualized therapies for toileting.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program (1ZIAMH002868) of the National Institutes of Mental Health (NCT01778504) as well as by the Intramural Research Program of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01778504?term=NCT01778504&rank=1

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. For the primary author, salary funding was provided by the United States Department of Defense. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, the United States Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as ‘a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.’ This work was prepared as part of the official duties of the authors.

References

- 1.Phelan K, McDermid HE. The 22q13.3 deletion syndrome (Phelan-McDermid Syndrome). Mol Syndromol 2012;2:186–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phelan K, Rogers RC, Boccuto L. Phelan-McDermid Syndrome. GeneReviews 2005; Updated 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1198/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet 2007;39:25–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarasua SM, Boccuto L, Sharp JL, et al. Clinical and genomic evaluation of 201 patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Hum Genet 2014;133:847–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolevzon A, Angarita B, Bush L, et al. Phelan-McDermid syndrome: a review of the literature and practice parameters for medical assessment and monitoring. J Neurodev Disord 2014;6:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabet AC, Rolland T, Ducloy M, et al. A framework to identify contributing genes in patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. NPJ Genom Med 2017;2:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soorya L, Kolevzon A, Zweifach J, et al. Prospective investigation of autism and genotype-phenotype correlations in 22q13 deletion syndrome and SHANK3 deficiency. Mol Autism 2013;4:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Gontard A Urinary incontinence in children with special needs. Nat Rev Urol 2013;10:667–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Wendt L, Similä S, Niskanen P et al. Development of bowel and bladder control in the mentally retarded. Dev Med Child Neurol 1990;32:515–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner C, Niemczyk J, Equit M et al. Incontinence in persons with Angelman syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niemczyk J, von Gontard A, Equit M et al. Incontinence in persons with Down Syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn 2017;36:1550–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroeger K, Sorensen R. A parent training model for toilet training children with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res 2010;54:556–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levato LE, Aponte CA, Wilkins J, et al. Use of urine alarms in toilet training children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A review. Res Dev Disabil 2016;53-54:232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, et al. Functional disorders: children and adolescents. Gastroenterology 2016; 150;1456–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RC, Kamm MA, Hinton JM, et al. The normal range and a simple diagram for recording whole gut transit time. Int J Colorectal Dis 1992;7:15–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southwell BR, Clarke MC, Sutcliffe J, et al. Colonic transit studies: normal values for adults and children with comparison of radiological and scintigraphic methods. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25:559–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan OI, Zhou X, Leon J, et al. Prospective longitudinal overnight video-EEG evaluation in Phelan-McDermid Syndrome. Epilepsy Behav 2018;80:312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines: American Guidance Services Incorporated; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leiter International Performance Scale - Revised. Wood Dale: Stoelting;1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition: Introductory and Technical Handbook. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation;2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.