Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is one the leading risk factors for chronic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer (HCC), which are a major global health problem. A large number of clinical studies have shown that chronic HBV persistent infection causes the dysfunction of innate and adaptive immune response involving monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells, T cells. Among these immune cells, cell subsets with suppressive features have been recognized such as myeloid derived suppressive cells(MDSC), NK-reg, T-reg, which represent a critical regulatory system during liver fibrogenesis or tumourigenesis. However, the mechanisms that link HBV-induced immune dysfunction and HBV-related liver diseases are not understood. In this review we summarize the recent studies on innate and adaptive immune cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC, and further discuss the potential mechanism of HBV-induced immunosuppressive cascade in HBV infection and consequences. It is hoped that this article will help ongoing research about the pathogenesis of HBV-related hepatic fibrosis and HBV-related HCC.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Liver fibrosis, Regulatory T cells, Regulatory natural killer cells, Dendritic cells, Monocytes

Core tip: We review that hepatitis B virus (HBV) induces suppressive function of the innate and adaptive immune cells in chronic HBV infection, and highlight that immune suppressive cascade contributes to the mechanism of HBV persistent infection. Further, we analyze the potential effects of HBV-induced immunosuppression in HBV-related fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, thus providing underlying research directions for future studies into the pathogenesis of HBV-related disease.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the presence of vaccines and therapeutic drugs, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major global health problem. More than 350 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HBV, and about 1 million people die each year from HBV-related complications[1]. Persistent HBV infection can lead to varying degrees of liver damage, which eventually leads to hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[2]. HBV belongs to the noncytopathic hepatic DNA virus family which only infect human and orangutan liver cells, and there is no evidence that the HBV can infect other non-hepatocyte cells[3]. HBV infection does not cause direct hepatocyte lesions, and the host's immune response determines whether it clears the virus or induces liver disease. In contrast that HBV-infected adults often develop self-limiting and transient hepatitis, and 95% of infections end with virus removal and the establishment of protective antibodies, the vast majority of neonatal vertical transmission of HBV from mother to child develops into chronic infection[4]. While divergent factors are involved in its pathogenesis, chronic HBV persistent infection is a complex process involving the interaction of the host immune system with the virus, which causes the incapacitation of the innate and adaptive immune response[3]. How HBV regulates the innate and adaptive immune cells, leading to persistent virus infection and further consequences, continues to be a research hotspot. Therefore, in this review, we summarize recent findings regarding the function and impairment of innate and adaptive immune cells, and discuss the potential mechanism of HBV-induced immune suppressive cascade in HBV infection and HBV-related liver diseases.

HBV-INDUCED IMMUNE SUPPRESSION CONTRIBUTES TO PERSISTENT INFECTION

HBV induces immune suppressive monocytes/macrophages

Monocytes/macrophages are important natural immune cells found in peripheral blood and organ tissue, and play multiple roles in the innate and acquired immune responses[5]. Monocytes/macrophage interact with lymphocytes through inhibitory or activating surface molecules. HBV stimulates monocyte/macrophage secretion of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)[6] and interleukin-10 (IL-10)[7], while inhibiting the secretion of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IL-12 induced by toll-like receptor (TLR2)[8,9]. Our study of HBV infection in a humanized mice model found that HBV induces human monocyte/macrophage differentiation into M2 macrophages, expressing IL-10 and other inhibitory cytokines[10]. Recently, we found that the anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β) and inhibitory cell surface molecules [Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-E] expressed in monocytes in patients with chronic HBV infection were significantly higher than those of healthy control[11]. Further experiments in vitro showed that HBsAg or HBV directly induced the expression of PD-L1 and HLA-E and the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines of monocytes from healthy adults[11]. Our group recently reported that HBV induces monocyte production of inflammatory cytokines via TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB signaling and STAT1-Ser727 phosphorylation and inhibits interferon (IFN)-α-induced stat1, stat2, and ch25h expression through the inhibition of STAT1-Tyr701 phosphorylation and in an IL-10-dependent, partially autocrine manner[12]. Therefore, HBV-induced suppressive monocytes/macrophages play a key role in the immune pathogenesis of chronic persistent infection.

HBV induces myeloid derived suppressive cells differentiation

Myeloid derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) are bone marrow-derived cell subsets with inhibitory functions, which can be divided into two main subgroups as M-MDSC (CD11b+HLA-DRlow/-CD14+CD15-) and PMN-MDSC (CD11b+ CD14-CD15+) according to their phenotypic and morphological characteristics[13]. MDSCs were first discovered in tumor tissue and play a role in the development, metastasis and immune escape of tumors[14]. Recent studies have found that MDSCs play a critical role in chronic HBV infection. The level of peripheral MDSCs in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients was significantly higher than that of healthy adults, and the percentage of MDSC cells had a significant correlation with HBV load in the plasma of HBV patients[15] and the mouse model[16]. Moreover, HBV induces monocytes differentiation of into MDSCs through the signal transduction pathway such as ERK/IL-16/STAT3/PI3K, thus inhibiting the activation and function of lymphocytes[17]. Drugs that target MDSCs could restore the responses of HBV-specific T cells from CHB patients ex vivo and prevent the increase of viral load in HBV mouse models[18,19]. In vitro, MDSCs secrete arginase and down-regulate the CD3ζ chain by missing arginine, thus inhibiting IFN-γ secretion from HBV-specific T cells[20]. In addition, MDSCs produce suppressive cytokines IL-10 to inhibit T-cell response in CHB patients[21]. MDSC not only directly inhibits T cell response through such mechanisms as arginase but also indirectly influences immunomodulatory function by inducing regulatory T cells (T-reg)[22,23].

HBV impairs the maturation and function of dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the professional antigen presenting cells, which process and present antigen to T cells, and are involved in the production of cytokines that influence T-cell polarization. The studies of DCs subsets in chronic HBV infection have primarily been limited to myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs(pDCs), two populations isolated from the peripheral blood. The frequency of mDCs in CHB patients shows a reduction which could be recovered by antiviral therapy[24]. There is a positive correlation of intrahepatic mDC subsets with serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and a significant inverse correlation with plasma HBV load[25]. The frequency of CD80+ and CD86+ mDCs showed slight differences between CHB patients and healthy donors after in vitro maturation[26]. It was also reported that PD-L1 expression on mDCs was increased in patients with active hepatitis B[27]. Increased ALT levels correlated with increased PD-L1 expression on mDCs, and impaired IFN-α production by pDCs[28]. Although some studies have reported that the function and frequency of pDCs were analogous between CHB patients and healthy controls[24], it has been demonstrated that HBV infection in pediatric patients showed a decreased frequency of pDCs, and the numbers of pDCs were restored by antiviral therapy[29,30]. The expression of the OX40 ligand was reduced in highly viremic patients while the expression of CD40 and CD86 was elevated in pDCs from CHB patients. Decreased expression of OX40L on TLR9-L-activated pDCs from viremic patients with HBV blocks their ability to induce the cytolytic activity of natural killer (NK) cells[31]. Monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) from HBV patients were impaired resulting in a reduction in T cell production of IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ because of lower IL-12 secretion[32]. In vitro, cytokine-induced human MoDCs maturation in the presence of HBsAg or HBV contributed to a significantly more tolerogenic DC phenotype as the reduced release of co-stimulatory molecules and IL-12 production as well as a T-cell stimulatory capacity, as evaluated by IFN-γ production and proliferation of T-cells[33].

HBV impairs NK cell function and induces NK cell differentiation

NK cells are another important innate immune cell, which can effectively and quickly identify and remove virally-infected cells without MHC restriction. NK cells are the major lymphocytes in the liver, accounting for about 30% of liver lymphocytes[34]. In the HBV transgenic mouse model, CD3-NK1.1+NK cells were found to be the main infiltrating lymphocytes of liver inflammation[35]. Functional defects of NK cells were found in CHB patients, showing a deactivation state[36]. The high level of inhibitory cytokine IL-10 in chronic HBV infection has an obvious inhibitory effect on the production of IFN-γ by NK cells[37]. The function of NK cells can be restored by IL-10 and TGF-β neutralizing antibodies in CHB patients[38].

The immunomodulatory function of NK cells has received much attention in recent years. The IFN-γ secreted by NK cells promotes the function of CD4+ T cells and enhance Th1 polarization[39]. However, under appropriate stimulation conditions, NK cells secrete immunomodulatory factor IL-10[40,41]. IL-10+ NK cells secrete TGF-β and IL-13, but do not secrete IFN-γ[42]. Our study found that the anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) and inhibitory cell surface molecules (PD-1 and CD94) expressed by NK cells in patients with chronic HBV infection were significantly higher than those of healthy adults. Further, in the co-culture experiment of monocytes and NK cells, HBV-induced suppressive monocytes were found to induce NK cell differentiation into regulatory NK cells (NK-regs) expressing anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 by PD-L1/PD-1 and HLA-E/CD94 conjugates[11]. The regulatory NK cells could not only directly inhibit the antiviral function of NK cells, but also inhibit HBV-specific T cell function by reducing the proliferation of T cells[11]. It has been reported that removing NK cells from peripheral blood can enhance the antiviral function of CD8+T cells[43]. These studies show that HBV-induced suppressive monocytes inhibit HBV-specific T-cell immune response by educating regulatory NK cells, which then leads to a chronic persistent infection of HBV.

HBV induces T cell exhaustion and regulatory T cell differentiation

Early studies have determined that the adaptive immune responses, especially HBV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune responses, play a crucial role in virus removal and the immune pathogenesis of hepatitis B[3]. CD4+T cells promote CTL responses and the production of neutralization antibodies, while CD8+ CTLs remove hepatocytes that are infected with HBV. IFN-γ and TNF-α secreted by T cells are critical cytokines that inhibit HBV replication[44,45]. In CHB infection, HBV-specific CD4+ and CD8+T cells did not respond adequately, also known as T cell exhaustion[46], showing a significant increase in the expression of co-inhibitory receptors PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3 and CD244 on the surface compared to a substantial decrease in cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion capacity. The long-term exposure to a high concentration of viral antigens is the direct cause of T cell immune tolerance and specific T cell exhaustion. Virus-specific T cells become gradually more exhausted with rising viral load and exhibit weakened effector function[47]. Viral load reduction restores the proportion of T cells and the function of HBV-specific T cells[48].

T-regs are a special subset of CD4+T cells that play a critical role in establishing and maintaining immune tolerance. It was reported that the proportion of peripheral CD4+CD25+Foxp3+T-reg cells in CHB patients was higher than that in healthy control and self-clearance of acute HBV infection[49,50], and was positively correlated with serum HBV load[51]. In addition, the proportion of hepatic infiltrating T-reg cells increased in CHB infection[52]. Multiple molecules participate in T-reg mediated immunosuppression, including CTLA-4, IL-10 and TGF-β. For example, IL-10 secreted by HBcAg-specific T-reg inhibited the secretion of IFN-γ from HBV-specific CD4+T cells, and blockade of IL-10 restored the secretion of IFN-γ of HBV-specific CD4+T cells[53]. T-regs from CHB patients could inhibit the proliferation and IFN-γ production of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) mediated by HBV antigen stimulation ex vivo[54]. Therefore, MDSCs and T-regs secrete a variety of effector molecules, directly or indirectly inhibiting T-cell responses, resulting in a chronic, persistent HBV infection.

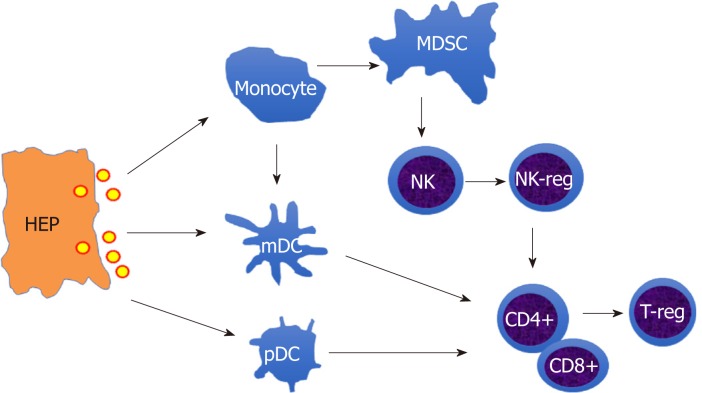

Therefore, the innate immune cells (monocytes/macrophages, DCs, NK cells) and adaptive immune cells (CD4+, CD8+T cells) are dampened in chronic HBV infection. As shown in Figure 1, HBV induces immune suppressive cells, such as MDSCs, NK-reg, and T-reg cells, to form an immunosuppressive cascade through inhibitory molecules, such as PD-L1, PD-1, IL-10, which contributes to chronic and persistent HBV infection.

Figure 1.

The schematic outline of hepatitis B virus-induced immune suppression network. The infected hepatocytes release hepatitis B virus virion to induce suppressive monocytes (Myeloid derived suppressive cells) and dendritic cells (tolerogenic dendritic cells), which initiate directly inducible T-reg to inhibit T cell activation or mediate indirectly by educating natural killer cell (NK) cells differentiation into NK-reg. HEP: Hepatocytes; MDSC: Myeloid derived suppressive cells; DC: Dendritic cells NK: Natural killer cell; T-reg: Regulatory T cell.

DOES HBV-INDUCED IMMUNE SUPPRESSION CONTRIBUTE TO LIVER FIBROSIS?

Liver fibrosis, which is a major global health problem for the lack of effective treatment, is caused by chronic liver injury of any etiology such as viral infection, alcoholic liver disease, and NASH[55]. The associated signals of liver injury cause the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), the activated HSCs trans-differentiate into myofibroblasts, and become the main source of extracellular matrix in the liver, leading to liver fibrosis. It is thus generally believed that HSCs are essential in the progression of liver fibrosis[56]. HBV is the leading risk factor for liver cirrhosis and HCC. Liver fibrosis is the early stage of liver cirrhosis and HCC, and can be reversed. Therefore, many studies are focusing on the immunopathogenesis of chronic HBV infection and the related liver fibrosis[57]. There have been few reports about the impact of HBV-induced immune suppression on fibrosis.

HBV-induced suppressive monocyte/macrophage in liver fibrosis

HBV interacts with receptors such as TLR2/4, which are expressed on Kupffer cells to produce a large number of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (TNF, CCL2) causing liver damage[58,59]. These inflammatory mediators induce peripheral monocytes to infiltrate into the liver, and then proliferate and differentiate into macrophages and exacerbate the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, further inducing the development of liver inflammation and fibrosis[60-62]. HBV-induced suppressive monocytes/macrophage, on the one hand, produce immunomodulatory molecules (IL-10, TGF-β, PD-L1/2) that inhibit the anti-fibrotic effects of NK cells and T cells; on the other hand, they secrete cytokines such as PDGF and TGF-β to activate HSC, prompting HSC survival[63,64]. A recent report showed that peripheral and ascitic MDSC numbers increase in cirrhosis and HCC, but its role in such pathology was not determined[65]. Conceptually, HBV-induced MDSCs impair the anti-fibrotic function of both T cells and NK cells by inhibiting IFN-γ secretion through PD-L1 or CTLA-4[66]. MDSC also inhibited cytotoxicity of NK cells through PD-L1 or TIGIT[67,68], thus protecting activated HSC from NK cell killing.

HBV-induced suppressive NK cells in liver fibrosis

NK cells secrete IFN-γ that inhibit HSC activation by abrogating profibrogenic TGF-β signaling and induce activated HSC apoptosis[69,70]. In addition, NK cells play a key role in the limitation of liver fibrosis through cytotoxicity of activated HSC[71]. Our recent study found a novel mechanism by which NK cells kill HSCs through TRAIL-involved degranulation manner[72]. In HBV infection, HBV-induced suppressive monocytes induce NK cell differentiation into NK-reg with decreased production of IFN-γ and increased IL-10[11]. Thus, it seems that HBV-induced NK-reg could promote HSC activation. But there is no evidence of the interaction between NK-regs and HSC, although it has been reported that HSCs modulate NK cells through a TGF-β-dependent emperipolesis in chronic HBV infection[73].

HBV-induced T cell immunosuppression in liver fibrosis

IL-2 secreted by CD4+ T cells is important in mediating the anti-fibrotic function of NK cells, and is impaired in HIV/HCV co-infection, which causes rapid progression of liver fibrosis[74]. More likely, HBV-induced T cell immunosuppression may also impair the anti-fibrotic function of NK cell. T-regs directly suppress NK cell degranulation of HSCs through CTLA-4, TGF-β1 and IL-8, and indirectly protect HSCs from NK cell killing by inhibiting MICA/B expressed on HSCs through IL-8 and TGF-β1[75]. In HBV-infected patients undergoing surgery for HCC, hepatic Th17 cells and T-reg were heightened in patients with advanced-stage HBV-related hepatic fibrosis[76]. On the other hand, T-regs could attenuate liver fibrosis by suppressing inflammation[77]. The role of HBV-induced T-regs in fibrosis needs to be further determined.

DOES HBV-INDUCED IMMUNE SUPPRESSION LEAD TO HCC?

HCC is the fifth most prevalent cancer in men and the second principal cause of cancer deaths worldwide[78]. HCC prevalence is very high in China, but the morbidity of HCC has also rising in the United States over the past few decades[79,80]. Early diagnosis and surgical resection are still the key to potential treatment, however, most patients with HCC have advanced-stage tumors with poor prognosis. HBV is one of the major risk factors for HCC, especially in areas where HBV is endemic, such as China[81]. The clinical scope of chronic HBV infection ranges from asymptomatic carrier status to CHB, which may evolve into liver cirrhosis and liver cancer[82]. It is estimated that 8%-20% untreated CHB adults develop cirrhosis of the liver within 5 years[83], and 2%-8% of those with cirrhosis develop HCC annually[84].

HBV prompts HCC development through direct and indirect mechanisms[85]. Chronic liver inflammation, insertional mutagenesis, and the host gene activation (cis’ effect) and transactivation by HBx and S proteins and oncogenic co-operativity (trans’ effect) were proposed as underlying mechanisms of HBV-related HCC development[86-88]. However, the underlying immunopathogenesis of HBV-related HCC development and progression is still not clear. There is a consensus that the immune system is critical in determining the clinical fate of HCC patients[89]. Viruses may also reprogram their immune microenvironment to induce immunosuppression and peripheral tolerance during chronic infections and eventually, tumourigenesis[90]. A meta-analysis of two immunosuppressed populations (transplant and HIV/AIDS patients) revealed a significantly increased incidence of several types of cancer, most of which were pathogen-driven[91]. Immunodeficiency, rather than other risk factors, is responsible for the increased incidence of cancer. The microenvironment of HBV-related HCC is more immunosuppressive than that of non-viral-related HCC[92]. Therefore, HBV-induced immune suppression may play a crucial role in HCC development and progression.

HBV-induced MDSCs in HCC

An increased frequency of CD14+HLA-DR-/low MDSCs was reported in both peripheral blood and tumor tissue of HCC patients[93]. Depletion of MDSCs restores production of granzyme B by CD8+ T cells and increases the number of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells in HCC patients[66], suggesting that HBV-induced MDSCs inhibit T cell anti-tumor effect. However, the frequency of CD14+PD-L1+ MDSCs is only positively correlated with HBV DNA load at the HCC stage[94]. Because of higher levels of PD-1+ CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues compared to nontumor tissues in HCC[95], PD-L1 expression induced by either HBV or HCC on monocytes/ MDSCs could be associated with impaired T-cell function in HBV-related HCC[66,96] although it has not been demonstrated whether HBV-induced suppressive monocytes were involved in pathogenesis.

HBV-induced NK-reg cells in HCC

NK cells from healthy donor PBMCs have significant cytotoxic function to HCC cell lines, and HepB3 cells transplanted in mice deficient of lymphocytes and NK cells (NOD/scid IL2RGnull) are significantly ostracized by i.p. administered NK cells in an NKG2D-dependent manner[97,98]. It has been reported that PD-1 is highly expressed on peripheral and tumor-infiltrating NK cells from HCC patients, suggesting NK cell exhaustion and poorer survival[99]. Since NK cells play a key role in immunological surveillance, HBV-induced NK cell suppression may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of HBV-related HCC. As our recent findings[11], PD-L1/PD-1 and CD94/HLA-E signaling control NK cell differentiation to NK-regs which in turn inhibit the anti-viral function of T cells and NK cells. Whether HBV-induced NK-regs are correlated with immune pathogenesis of HCC remains unclear.

HBV-induced T-reg in HCC

Both the absolute numbers and proportion of CD4+CD25+ T-reg cells significantly increase in the edge region of the tumor, compared to the non-tumor region[100]. In vitro, Huh7 cells inhibit CD4+CD25- T-cell proliferation, promote CD4+CD25+ T-cell proliferation, and enhance their suppressor ability[101]. It seems that the induction of T-regs could be effected by not only the HBV infection but also by the HCC, because the increased CD4+CD25+ T-regs population and upregulated T-regs-related genes are induced by HepG2.2.15[102]. A decreased infiltration of CD8+ T cells concurrent with abundant accumulation of T-regs was found in tumor regions compared with non-tumor regions[103]. Increased Foxp3+ T-regs not only means poor survival, but also presents a prognostic predictor in patients with early-stage HCC[104]. It indicates that HBV-induced T-regs might be involved in immune pathogenesis of HBV-related HCC.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Immune suppression induced by HBV infection has been well described by a number of different mechanisms for the different immune cells[10,11,15,27,36,53]. HBV induces immune suppressive cells, such as MDSCs, NK-reg, and T-reg cells, through an immunosuppressive cascade. The excessive immunosuppression could contribute to an HBV persistent infection and the progression of liver fibrosis and HCC[105]. Better understanding the immunopathogenesis of HBV-related hepatic fibrosis and HCC will be helpful for the intervention and management of HBV progression and the treatment of related end-stage liver diseases in the clinic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. John Sulivan for English and grammatical revision.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Peer-review started: March 26, 2019

First decision: April 16, 2019

Article in press: June 1, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Choe BH, Cunha C, Park YM S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Tian-Yang Li, Infectious Disease, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China.

Yang Yang, Institute of Liver diseases, the First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130061, Jilin Province, China.

Guo Zhou, Infectious Disease, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China.

Zheng-Kun Tu, Infectious Disease, Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510000, Guangdong Province, China. tuzhengkun@hotmail.com; Institute of Liver diseases, the First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130061, Jilin Province, China.

References

- 1.Dandri M, Locarnini S. New insight in the pathobiology of hepatitis B virus infection. Gut. 2012;61 Suppl 1:i6–17. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeger C, Mason WS. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology. 2015;479-480:672–686. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:23–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan CQ, Zhang JX. Natural History and Clinical Consequences of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005;2:36–40. doi: 10.7150/ijms.2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Zheng HW, Chen H, Xing ZZ, You H, Cong M, Jia JD. Hepatitis B virus particles preferably induce Kupffer cells to produce TGF-β1 over pro-inflammatory cytokines. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li M, Sun R, Xu L, Yin W, Chen Y, Zheng X, Lian Z, Wei H, Tian Z. Kupffer Cells Support Hepatitis B Virus-Mediated CD8+ T Cell Exhaustion via Hepatitis B Core Antigen-TLR2 Interactions in Mice. J Immunol. 2015;195:3100–3109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visvanathan K, Skinner NA, Thompson AJ, Riordan SM, Sozzi V, Edwards R, Rodgers S, Kurtovic J, Chang J, Lewin S, Desmond P, Locarnini S. Regulation of Toll-like receptor-2 expression in chronic hepatitis B by the precore protein. Hepatology. 2007;45:102–110. doi: 10.1002/hep.21482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, Chen Z, Hu C, Qian F, Cheng Y, Wu M, Shi B, Chen J, Hu Y, Yuan Z. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen selectively inhibits TLR2 ligand-induced IL-12 production in monocytes/macrophages by interfering with JNK activation. J Immunol. 2013;190:5142–5151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bility MT, Cheng L, Zhang Z, Luan Y, Li F, Chi L, Zhang L, Tu Z, Gao Y, Fu Y, Niu J, Wang F, Su L. Hepatitis B virus infection and immunopathogenesis in a humanized mouse model: Induction of human-specific liver fibrosis and M2-like macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004032. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Zhai N, Wang Z, Song H, Yang Y, Cui A, Li T, Wang G, Niu J, Crispe IN, Su L, Tu Z. Regulatory NK cells mediated between immunosuppressive monocytes and dysfunctional T cells in chronic HBV infection. Gut. 2018;67:2035–2044. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song H, Tan G, Yang Y, Cui A, Li H, Li T, Wu Z, Yang M, Lv G, Chi X, Niu J, Zhu K, Crispe IN, Su L, Tu Z. Hepatitis B Virus-Induced Imbalance of Inflammatory and Antiviral Signaling by Differential Phosphorylation of STAT1 in Human Monocytes. J Immunol. 2019;202:2266–2275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, Mandruzzato S, Murray PJ, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Rodriguez PC, Sica A, Umansky V, Vonderheide RH, Gabrilovich DI. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lv Y, Cui M, Lv Z, Lu J, Zhang X, Zhao Z, Wang Y, Gao L, Tsuji NM, Yan H. Expression and significance of peripheral myeloid-derived suppressor cells in chronic hepatitis B patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen S, Akbar SM, Abe M, Hiasa Y, Onji M. Immunosuppressive functions of hepatic myeloid-derived suppressor cells of normal mice and in a murine model of chronic hepatitis B virus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166:134–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Z, Li J, Yu X, Zhang D, Ren G, Shi B, Wang C, Kosinska AD, Wang S, Zhou X, Kozlowski M, Hu Y, Yuan Z. Polarization of Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Is Mediated via ERK/IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Feedback and Restrains the Activation of T Cells in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J Immunol. 2015;195:4873–4883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pang X, Song H, Zhang Q, Tu Z, Niu J. Hepatitis C virus regulates the production of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells through PI3K pathway and autocrine signaling. Clin Immunol. 2016;164:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou HS, Hsieh CC, Yang HR, Wang L, Arakawa Y, Brown K, Wu Q, Lin F, Peters M, Fung JJ, Lu L, Qian S. Hepatic stellate cells regulate immune response by way of induction of myeloid suppressor cells in mice. Hepatology. 2011;53:1007–1019. doi: 10.1002/hep.24162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pallett LJ, Gill US, Quaglia A, Sinclair LV, Jover-Cobos M, Schurich A, Singh KP, Thomas N, Das A, Chen A, Fusai G, Bertoletti A, Cantrell DA, Kennedy PT, Davies NA, Haniffa M, Maini MK. Metabolic regulation of hepatitis B immunopathology by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Med. 2015;21:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nm.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang A, Zhang B, Yan W, Wang B, Wei H, Zhang F, Wu L, Fan K, Guo Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection through PD-1-induced IL-10. J Immunol. 2014;193:5461–5469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoso A, Mazza EM, Bicciato S, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Serafini P, Inverardi L. Human fibrocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells express IDO and promote tolerance via Treg-cell expansion. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:3307–3319. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhai N, Li H, Song H, Yang Y, Cui A, Li T, Niu J, Crispe IN, Su L, Tu Z. Hepatitis C Virus Induces MDSCs-Like Monocytes through TLR2/PI3K/AKT/STAT3 Signaling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Molen RG, Sprengers D, Biesta PJ, Kusters JG, Janssen HL. Favorable effect of adefovir on the number and functionality of myeloid dendritic cells of patients with chronic HBV. Hepatology. 2006;44:907–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.21340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, Chen D, Yao J, Zhang H, Jin L, Shi M, Zhang H, Wang FS. Increased infiltration of intrahepatic DC subsets closely correlate with viral control and liver injury in immune active pediatric patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Molen RG, Sprengers D, Binda RS, de Jong EC, Niesters HG, Kusters JG, Kwekkeboom J, Janssen HL. Functional impairment of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2004;40:738–746. doi: 10.1002/hep.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Zhang Z, Chen W, Zhang Z, Li Y, Shi M, Zhang J, Chen L, Wang S, Wang FS. B7-H1 up-regulation on myeloid dendritic cells significantly suppresses T cell immune function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Immunol. 2007;178:6634–6641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gehring AJ, Ann D'Angelo J. Dissecting the dendritic cell controversy in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:283–291. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan XZ, Wang M, Li HW, Zhuang H, Xu D, Wang FS. Decreased frequency and function of circulating plasmocytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in hepatitis B virus infected humans. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:637–646. doi: 10.1007/s10875-004-6249-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo J, Gao Y, Guo Z, Zhang LR, Wang B, Wang SP. Frequencies of dendritic cells and Toll-like receptor 3 in neonates born to HBsAg-positive mothers with different HBV serological profiles. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:62–70. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinet J, Dufeu-Duchesne T, Bruder Costa J, Larrat S, Marlu A, Leroy V, Plumas J, Aspord C. Altered functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells and reduced cytolytic activity of natural killer cells in patients with chronic HBV infection. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1586–1596.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckebaum S, Cicinnati VR, Zhang X, Ferencik S, Frilling A, Grosse-Wilde H, Broelsch CE, Gerken G. Hepatitis B virus-induced defect of monocyte-derived dendritic cells leads to impaired T helper type 1 response in vitro: Mechanisms for viral immune escape. Immunology. 2003;109:487–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Op den Brouw ML, Binda RS, van Roosmalen MH, Protzer U, Janssen HL, van der Molen RG, Woltman AM. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen impairs myeloid dendritic cell function: A possible immune escape mechanism of hepatitis B virus. Immunology. 2009;126:280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng H, Wisse E, Tian Z. Liver natural killer cells: Subsets and roles in liver immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:328–336. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortega-Prieto AM, Dorner M. Immune Evasion Strategies during Chronic Hepatitis B and C Virus Infection. Vaccines (Basel) 2017;5:pii: E24. doi: 10.3390/vaccines5030024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stelma F, de Niet A, Tempelmans Plat-Sinnige MJ, Jansen L, Takkenberg RB, Reesink HW, Kootstra NA, van Leeuwen EM. Natural Killer Cell Characteristics in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection Are Associated With HBV Surface Antigen Clearance After Combination Treatment With Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2a and Adefovir. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1042–1051. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Micco L, Peppa D, Loggi E, Schurich A, Jefferson L, Cursaro C, Panno AM, Bernardi M, Brander C, Bihl F, Andreone P, Maini MK. Differential boosting of innate and adaptive antiviral responses during pegylated-interferon-alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2013;58:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan AT, Hoang LT, Chin D, Rasmussen E, Lopatin U, Hart S, Bitter H, Chu T, Gruenbaum L, Ravindran P, Zhong H, Gane E, Lim SG, Chow WC, Chen PJ, Petric R, Bertoletti A, Hibberd ML. Reduction of HBV replication prolongs the early immunological response to IFNα therapy. J Hepatol. 2014;60:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martín-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conroy MJ, Mac Nicholas R, Grealy R, Taylor M, Otegbayo JA, O'Dea S, Mulcahy F, Ryan T, Norris S, Doherty DG. Circulating CD56dim natural killer cells and CD56+ T cells that produce interferon-γ or interleukin-10 are expanded in asymptomatic, E antigen-negative patients with persistent hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:335–345. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan YLT, Zuo J, Inman C, Croft W, Begum J, Croudace J, Kinsella F, Maggs L, Nagra S, Nunnick J, Abbotts B, Craddock C, Malladi R, Moss P. NK cells produce high levels of IL-10 early after allogeneic stem cell transplantation and suppress development of acute GVHD. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48:316–329. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagage S, John B, Krock BL, Hall AO, Randall LM, Karp CL, Simon MC, Hunter CA. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor promotes IL-10 production by NK cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:1661–1670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peppa D, Gill US, Reynolds G, Easom NJ, Pallett LJ, Schurich A, Micco L, Nebbia G, Singh HD, Adams DH, Kennedy PT, Maini MK. Up-regulation of a death receptor renders antiviral T cells susceptible to NK cell-mediated deletion. J Exp Med. 2013;210:99–114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guidotti LG, Ishikawa T, Hobbs MV, Matzke B, Schreiber R, Chisari FV. Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xia Y, Stadler D, Lucifora J, Reisinger F, Webb D, Hösel M, Michler T, Wisskirchen K, Cheng X, Zhang K, Chou WM, Wettengel JM, Malo A, Bohne F, Hoffmann D, Eyer F, Thimme R, Falk CS, Thasler WE, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. Interferon-γ and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Produced by T Cells Reduce the HBV Persistence Form, cccDNA, Without Cytolysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:194–205. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye B, Liu X, Li X, Kong H, Tian L, Chen Y. T-cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis B infection: Current knowledge and clinical significance. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1694. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuller MJ, Zajac AJ. Ablation of CD8 and CD4 T cell responses by high viral loads. J Immunol. 2003;170:477–486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boni C, Penna A, Ogg GS, Bertoletti A, Pilli M, Cavallo C, Cavalli A, Urbani S, Boehme R, Panebianco R, Fiaccadori F, Ferrari C. Lamivudine treatment can overcome cytotoxic T-cell hyporesponsiveness in chronic hepatitis B: New perspectives for immune therapy. Hepatology. 2001;33:963–971. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.TrehanPati N, Kotillil S, Hissar SS, Shrivastava S, Khanam A, Sukriti S, Mishra SK, Sarin SK. Circulating Tregs correlate with viral load reduction in chronic HBV-treated patients with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoop JN, van der Molen RG, Baan CC, van der Laan LJ, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG, Janssen HL. Regulatory T cells contribute to the impaired immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2005;41:771–778. doi: 10.1002/hep.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoop JN, van der Molen RG, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG, Janssen HL. Inhibition of viral replication reduces regulatory T cells and enhances the antiviral immune response in chronic hepatitis B. Virology. 2007;361:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu D, Fu J, Jin L, Zhang H, Zhou C, Zou Z, Zhao JM, Zhang B, Shi M, Ding X, Tang Z, Fu YX, Wang FS. Circulating and liver resident CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells actively influence the antiviral immune response and disease progression in patients with hepatitis B. J Immunol. 2006;177:739–747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kondo Y, Kobayashi K, Ueno Y, Shiina M, Niitsuma H, Kanno N, Kobayashi T, Shimosegawa T. Mechanism of T cell hyporesponsiveness to HBcAg is associated with regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4310–4317. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng G, Li S, Wu W, Sun Z, Chen Y, Chen Z. Circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology. 2008;123:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friedman SL. Evolving challenges in hepatic fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:425–436. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quero L, Hanser E, Manigold T, Tiaden AN, Kyburz D. TLR2 stimulation impairs anti-inflammatory activity of M2-like macrophages, generating a chimeric M1/M2 phenotype. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:245. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1447-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondo Y, Ueno Y, Shimosegawa T. Toll-like receptors signaling contributes to immunopathogenesis of HBV infection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:810939. doi: 10.1155/2011/810939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marra F, Tacke F. Roles for chemokines in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:577–594.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki R, Devhare PB, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. Hepatitis C virus-induced CCL5 secretion from macrophages activates hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017;66:746–757. doi: 10.1002/hep.29170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Q, Wang Y, Zhai N, Song H, Li H, Yang Y, Li T, Guo X, Chi B, Niu J, Crispe IN, Su L, Tu Z. HCV core protein inhibits polarization and activity of both M1 and M2 macrophages through the TLR2 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36160. doi: 10.1038/srep36160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao D, Xu H, Guo G, Ruan Z, Fei L, Xie Z, Wu Y, Chen Y. Intrahepatic expression of programmed death-1 and its ligands in patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Inflammation. 2013;36:110–120. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marra F, Aleffi S, Galastri S, Provenzano A. Mononuclear cells in liver fibrosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:345–358. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elwan N, Salem ML, Kobtan A, El-Kalla F, Mansour L, Yousef M, Al-Sabbagh A, Zidan AA, Abd-Elsalam S. High numbers of myeloid derived suppressor cells in peripheral blood and ascitic fluid of cirrhotic and HCC patients. Immunol Invest. 2018;47:169–180. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2017.1407787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalathil S, Lugade AA, Miller A, Iyer R, Thanavala Y. Higher frequencies of GARP(+)CTLA-4(+)Foxp3(+) T regulatory cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients are associated with impaired T-cell functionality. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2435–2444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Husain Z, Huang Y, Seth P, Sukhatme VP. Tumor-derived lactate modifies antitumor immune response: Effect on myeloid-derived suppressor cells and NK cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:1486–1495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sarhan D, Cichocki F, Zhang B, Yingst A, Spellman SR, Cooley S, Verneris MR, Blazar BR, Miller JS. Adaptive NK Cells with Low TIGIT Expression Are Inherently Resistant to Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5696–5706. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weng H, Mertens PR, Gressner AM, Dooley S. IFN-gamma abrogates profibrogenic TGF-beta signaling in liver by targeting expression of inhibitory and receptor Smads. J Hepatol. 2007;46:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weng HL, Feng DC, Radaeva S, Kong XN, Wang L, Liu Y, Li Q, Shen H, Gao YP, Müllenbach R, Munker S, Huang T, Chen JL, Zimmer V, Lammert F, Mertens PR, Cai WM, Dooley S, Gao B. IFN-γ inhibits liver progenitor cell proliferation in HBV-infected patients and in 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine diet-fed mice. J Hepatol. 2013;59:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fasbender F, Widera A, Hengstler JG, Watzl C. Natural Killer Cells and Liver Fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2016;7:19. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li T, Yang Y, Song H, Li H, Cui A, Liu Y, Su L, Crispe IN, Tu Z. Activated NK cells kill hepatic stellate cells via p38/PI3K signaling in a TRAIL-involved degranulation manner. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105:695–704. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2A0118-031RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi J, Zhao J, Zhang X, Cheng Y, Hu J, Li Y, Zhao X, Shang Q, Sun Y, Tu B, Shi L, Gao B, Wang FS, Zhang Z. Activated hepatic stellate cells impair NK cell anti-fibrosis capacity through a TGF-β-dependent emperipolesis in HBV cirrhotic patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44544. doi: 10.1038/srep44544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Glässner A, Eisenhardt M, Kokordelis P, Krämer B, Wolter F, Nischalke HD, Boesecke C, Sauerbruch T, Rockstroh JK, Spengler U, Nattermann J. Impaired CD4⁺ T cell stimulation of NK cell anti-fibrotic activity may contribute to accelerated liver fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV patients. J Hepatol. 2013;59:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langhans B, Alwan AW, Krämer B, Glässner A, Lutz P, Strassburg CP, Nattermann J, Spengler U. Regulatory CD4+ T cells modulate the interaction between NK cells and hepatic stellate cells by acting on either cell type. J Hepatol. 2015;62:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li X, Su Y, Hua X, Xie C, Liu J, Huang Y, Zhou L, Zhang M, Li X, Gao Z. Levels of hepatic Th17 cells and regulatory T cells upregulated by hepatic stellate cells in advanced HBV-related liver fibrosis. J Transl Med. 2017;15:75. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milosavljevic N, Gazdic M, Simovic Markovic B, Arsenijevic A, Nurkovic J, Dolicanin Z, Jovicic N, Jeftic I, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate liver fibrosis by suppressing Th17 cells - an experimental study. Transpl Int. 2018;31:102–115. doi: 10.1111/tri.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee JS. The mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2015;21:220–229. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2015.21.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Njei B, Rotman Y, Ditah I, Lim JK. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology. 2015;61:191–199. doi: 10.1002/hep.27388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hung TH, Liang CM, Hsu CN, Tai WC, Tsai KL, Ku MK, Wang JW, Tseng KL, Yuan LT, Nguang SH, Yang SC, Wu CK, Hsu PI, Wu DC, Chuah SK. Association between complicated liver cirrhosis and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S84–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O'Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:222–232. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao LH, Liu X, Yan HX, Li WY, Zeng X, Yang Y, Zhao J, Liu SP, Zhuang XH, Lin C, Qin CJ, Zhao Y, Pan ZY, Huang G, Liu H, Zhang J, Wang RY, Yang Y, Wen W, Lv GS, Zhang HL, Wu H, Huang S, Wang MD, Tang L, Cao HZ, Wang L, Lee TL, Jiang H, Tan YX, Yuan SX, Hou GJ, Tao QF, Xu QG, Zhang XQ, Wu MC, Xu X, Wang J, Yang HM, Zhou WP, Wang HY. Genomic and oncogenic preference of HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12992. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ali A, Abdel-Hafiz H, Suhail M, Al-Mars A, Zakaria MK, Fatima K, Ahmad S, Azhar E, Chaudhary A, Qadri I. Hepatitis B virus, HBx mutants and their role in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10238–10248. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vandeven N, Nghiem P. Pathogen-driven cancers and emerging immune therapeutic strategies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:9–14. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lim CJ, Lee YH, Pan L, Lai L, Chua C, Wasser M, Lim TKH, Yeong J, Toh HC, Lee SY, Chan CY, Goh BK, Chung A, Heikenwälder M, Ng IO, Chow P, Albani S, Chew V. Multidimensional analyses reveal distinct immune microenvironment in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2019;68:916–927. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Krüger C, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:234–243. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang ZY, Xu P, Li JH, Zeng CH, Song HF, Chen H, Zhu YB, Song YY, Lu HL, Shen CP, Zhang XG, Wu MY, Wang XF. Clinical Significance of Dynamics of Programmed Death Ligand-1 Expression on Circulating CD14+ Monocytes and CD19+ B Cells with the Progression of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Viral Immunol. 2017;30:224–231. doi: 10.1089/vim.2016.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wu K, Kryczek I, Chen L, Zou W, Welling TH. Kupffer cell suppression of CD8+ T cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by B7-H1/programmed death-1 interactions. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8067–8075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nan J, Xing YF, Hu B, Tang JX, Dong HM, He YM, Ruan DY, Ye QJ, Cai JR, Ma XK, Chen J, Cai XR, Lin ZX, Wu XY, Li X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced LOX-1+ CD15+ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunology. 2018;154:144–155. doi: 10.1111/imm.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Curran CS, Sharon E. PD-1 immunobiology in autoimmune hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2017;44:428–432. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kamiya T, Chang YH, Campana D. Expanded and Activated Natural Killer Cells for Immunotherapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:574–581. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu Y, Cheng Y, Xu Y, Wang Z, Du X, Li C, Peng J, Gao L, Liang X, Ma C. Increased expression of programmed cell death protein 1 on NK cells inhibits NK-cell-mediated anti-tumor function and indicates poor prognosis in digestive cancers. Oncogene. 2017;36:6143–6153. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang XH, Yamagiwa S, Ichida T, Matsuda Y, Sugahara S, Watanabe H, Sato Y, Abo T, Horwitz DA, Aoyagi Y. Increase of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cells in the liver of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cao M, Cabrera R, Xu Y, Firpi R, Zhu H, Liu C, Nelson DR. Hepatocellular carcinoma cell supernatants increase expansion and function of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Lab Invest. 2007;87:582–590. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang HH, Mei MH, Fei R, Liu F, Wang JH, Liao WJ, Qin LL, Wei L, Chen HS. Regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis B patients affect the immunopathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing the anti-tumour immune responses. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17 Suppl 1:34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fu J, Xu D, Liu Z, Shi M, Zhao P, Fu B, Zhang Z, Yang H, Zhang H, Zhou C, Yao J, Jin L, Wang H, Yang Y, Fu YX, Wang FS. Increased regulatory T cells correlate with CD8 T-cell impairment and poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2328–2339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang F, Jing X, Li G, Wang T, Yang B, Zhu Z, Gao Y, Zhang Q, Yang Y, Wang Y, Wang P, Du Z. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are associated with the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2012;32:644–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kondo Y, Shimosegawa T. Significant roles of regulatory T cells and myeloid derived suppressor cells in hepatitis B virus persistent infection and hepatitis B virus-related HCCs. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:3307–3322. doi: 10.3390/ijms16023307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]