Abstract

Purpose

Recent evidence suggests that cough hypersensitivity may be a common feature of chronic cough in adults. However, the clinical relevance remains unclear. This study evaluated the cough-related symptom profile and the clinical relevance and impact of cough hypersensitivity in adults with chronic cough.

Methods

This cross-sectional multi-center study compared cough-related laryngeal sensations and cough triggers in patients with unexplained chronic cough following investigations and in unselected patients newly referred for chronic cough. A structured questionnaire was used to assess abnormal laryngeal sensations and cough triggers. Patients with unexplained cough were also evaluated using the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) and a cough visual analogue scale (VAS), and these scores were assessed for correlations with the number of triggers and laryngeal sensations.

Results

This study recruited 478 patients, including 62 with unexplained chronic cough and 416 with chronic cough. Most participants reported abnormal laryngeal sensations and cough triggers. Laryngeal sensations (4.4 ± 1.5 vs. 3.9 ± 1.9; P = 0.049) and cough triggers (6.9 ± 2.6 vs. 5.0 ± 2.8; P < 0.001) were more frequent in patients with unexplained chronic cough than in those with chronic cough. The number of triggers and laryngeal sensations score significantly correlated with LCQ (r = −0.51, P < 0.001) and cough VAS score (r = 0.53, P < 0.001) in patients with unexplained chronic cough.

Conclusions

Cough hypersensitivity may be a common feature in adult patients with chronic cough, especially those with unexplained chronic cough. Cough-related health status and cough severity were inversely associated with the number of triggers and laryngeal sensations, suggesting potential relevance of assessing cough hypersensitivity in chronic cough patients.

Keywords: Cough, hypersensitivity, symptom assessment

INTRODUCTION

Cough is a protective reflex of the airways against the inhalation and aspiration of irritants. However, a dysregulated cough reflex is a significant morbidity. Clinical practice guidelines1,2 classify coughing by its duration because persistent cough usually requires further clinical attention. In particular, chronic cough (defined as a cough lasting longer than 8 weeks in adults) is an important condition, with high prevalence and a substantial impact on patient quality of life.3,4 However, the duration-based definition of chronic cough is subjective and may not capture the intrinsic nature of the clinical condition.5,6

Recently, a unifying paradigm, cough hypersensitivity syndrome, was proposed for chronic cough in adults.7,8 This syndrome is defined as a clinical entity, in which chronic cough is the major presenting problem, characterized by sensitivity to low levels of thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimuli. It is an “umbrella” concept proposed to encompass different cough-related conditions and unexplained cough.7,9 Observational studies have described symptoms such as urge to cough, allotussia (cough due to non-tussive stimuli), and laryngeal paresthesia (abnormal laryngeal sensation) in patients either with unexplained cough or unselected chronic cough.10,11,12 These findings suggested that cough hypersensitivity is a major feature of chronic cough in adults. However, the clinical relevance of cough hypersensitivity is still poorly understood and warrants validation in different populations. Previous studies10,11,12 lacked a comparison group and did not assess correlations with clinical outcomes.

We hypothesized that cough hypersensitivity is common in chronic cough but is more prevalent in unexplained chronic cough. The present study aimed to (1) describe a symptom profile of cough hypersensitivity, (2) assess its clinical relevance in adult patients with chronic cough, and (3) compare cough-related sensations and cough triggers of unexplained chronic cough patients compared with those of newly referred chronic cough patients. The clinical relevance of cough hypersensitivity symptom profiles were examined by analyzing their correlations with Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) and cough visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, 2 common tools for cough assessment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This is a cross-sectional analysis comparing unexplained chronic cough patients and patients newly referred for chronic cough. Patients were recruited between February 2016 and January 2019 from specialist clinics at 6 tertiary hospitals in Korea. Patients with unexplained chronic cough were defined as those having cough of an unknown etiology after thorough investigation and therapeutic trials by specialist physicians based on current practice guidelines.13 The investigation and therapeutic trials included those for common cough-related conditions (upper airway diseases, asthma, eosinophilic bronchitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease) in all patients and chest computed tomography scan or bronchoscopy in cases needed.13 Patients newly referred for chronic cough were an unselected group with chronic cough irrespective of underlying conditions, who did not undergo diagnostic evaluation or treatment at the referral clinics. All participants were consecutively recruited and provided informed consent. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Assessment

Structured questionnaires included demographic factors, such as age, sex, and smoking status, as well as characteristics of cough. The Cough Hypersensitivity Questionnaire (CHQ) was used to record cough-associated symptoms. The CHQ is a new questionnaire that simply records the number of triggers and laryngeal sensations in a structured manner. It was originally developed based on literature reviews and patient interviews.14 The current version of the CHQ consists of 23 items evaluating cough-associated laryngeal sensations and triggers. It showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.90) in a recent study.15 The response scale is binary (yes/no). The 7 questions about laryngeal sensations were formulated as, “Have you experienced any of the following in relation to your cough within the last 2 weeks?”, whereas the 16 questions about cough triggers were formulated as, “Do any of the following trigger your cough?” The total number of questions was 23, consisting of cough-related sensations (7) and cough triggers (16). The sum of each domain was obtained, a higher score indicating a greater number of sensations or triggers associated with cough.

Translation resulting in the Korean version of the CHQ14 followed previous methodology.16 Briefly, the CHQ was translated into Korean by 2 bilingual professionals, with this version back-translated into English by 2 other professionals. To check its comprehensibility and validate its cross-cultural adaptation, a pilot study was performed on 10 subjects. They were asked to respond to each item and report any difficulties in interpretation.

The impact and severity of cough were also evaluated in patients with unexplained chronic cough. Cough-specific quality of life was assessing using the Korean version of the LCQ,17 with total scores ranging from 3 to 21. Cough severity was measured using a paper-based cough VAS, with a range of 0–10, where 0 indicates no cough and 10 indicates for the most severe cough.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were presented as frequency and proportion. The numbers of cough-related sensations and trigger factors were evaluated using histograms. Differences between 2 groups were evaluated using t tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests, as appropriate. Linear regression analyses were performed to assess factors associated with CHQ scores. Correlations of CHQ with LCQ or cough VAS scores were evaluated using Spearman's correlation tests. A 2-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

This study recruited a total of 478 patients, including 416 with chronic cough and 62 with unexplained chronic cough, from 6 tertiary hospitals. The baseline characteristics of the 2 groups are summarized in Table 1. Overall mean age was 55.1 ± 15.7 years, and most patients were women (68.4%) and never smokers (74.7%). However, age (59.8 ± 13.0 vs. 54.4 ± 16.0 years, P = 0.012) and the percentage of women (85.5% vs. 65.9%, P = 0.002) were significantly higher, and duration of cough significantly longer (P < 0.001) in patients with unexplained chronic cough than in patients with chronic cough.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with chronic cough.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 478) | Unexplained chronic cough (n = 62) | Chronic cough (n = 416) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.1 ± 15.7 | 59.8 ± 13.0 | 54.4 ± 16.0 | 0.012 | |

| Female sex (%) | 68.4 | 85.5 | 65.9 | 0.002 | |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.066 | ||||

| Never smoker | 74.7 | 85.5 | 73.0 | ||

| Ex-smoker | 17.7 | 12.9 | 18.4 | ||

| Current smoker | 7.7 | 1.6 | 8.6 | ||

| Cough duration (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| 2–6 months | 44.0 | 0.0 | 50.6 | ||

| 6–12 months | 13.8 | 6.5 | 15.0 | ||

| 1–5 years | 21.6 | 43.6 | 18.3 | ||

| > 5 years | 20.6 | 50.0 | 16.1 | ||

| Total LCQ score | 10.7 ± 2.9 | ||||

| Physical | 4.1 ± 0.9 | ||||

| Psychological | 3.3 ± 1.1 | ||||

| Social | 3.3 ± 1.4 | ||||

| Cough VAS | 6.1 ± 2.0 | ||||

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or percentage.

VAS, visual analogue scale; LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

*Difference between unexplained chronic cough and chronic cough groups.

Cough-related laryngeal sensations

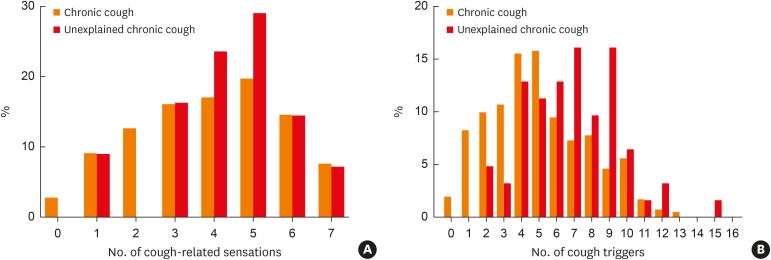

Overall, the mean number of positive responses in all subjects was 4.0 ± 1.8 (Table 2). More than half the respondents reported a tickle in the throat (68.8%), throat clearing (68.4%), dry throat (66.7%), urge to cough (64.2%), and irritation in the throat (52.5%). The number of cough-related laryngeal sensations was significantly higher in patients with unexplained chronic cough than in those with chronic cough (4.4 ± 1.5 vs. 3.9 ± 1.9; P = 0.049; Table 2). Specifically, dry throat (82.3% vs. 64.9%; P = 0.005) and irritation in the throat (66.1% vs. 50.9%; P = 0.028) were significantly more frequent in patients with unexplained chronic cough than in those with chronic cough. All of the patients with unexplained chronic cough reported at least 1 cough-related laryngeal sensation (Fig. 1A).

Table 2. Cough-related laryngeal sensations in patients with chronic cough.

| Q. Have you experienced any of the following in relation to your cough within the last 2 weeks? | Total (n = 478) | Unexplained chronic cough (n = 62) | Chronic cough (n = 416) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tickle in throat (%) | 68.8 | 75.8 | 68.3 | 0.20 |

| Throat clearing (%) | 68.4 | 67.7 | 69.0 | 0.90 |

| Dry throat (%) | 66.7 | 82.3 | 64.9 | 0.005 |

| Urge to cough (%) | 64.2 | 69.4 | 63.9 | 0.37 |

| Irritation in throat (%) | 52.5 | 66.1 | 50.9 | 0.021 |

| Sensation in chest (%) | 42.7 | 38.7 | 43.6 | 0.50 |

| Itchy throat (%) | 34.5 | 40.3 | 33.9 | 0.30 |

| Total cough-related sensation score* | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 0.049 |

*Total score indicates the sum of the number of positive responses; †Difference between the unexplained chronic cough and chronic cough groups.

Fig. 1.

The number of (A) cough-related laryngeal sensations and (B) cough triggers in patients with chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough.

Cough triggers

Overall, the mean number of positive responses to cough triggers was 5.3 ± 2.8 (Table 3). Cold air (75.2%), dry air (58.1%), sputum (54.1%), and smoke (53.1%) were positive in more than half of overall patients. Patients with unexplained chronic cough reported a significantly higher number of cough triggers than those with chronic cough (6.9 ± 2.6 vs. 5.0 ± 2.8; P < 0.001; Table 3). All subjects in the unexplained chronic cough group reported at least 2 cough triggers (Fig. 1B). The percentages of patients reporting responses to dry air (79.0% vs. 55.0%; P < 0.001), eating (53.2% vs. 15.3%; P < 0.001), talking (58.1% vs. 40.4%; P = 0.009), perfume (45.2% vs. 25.7%; P = 0.002), heartburn (41.9% vs. 12.1%; P < 0.001), indigestion (40.3% vs. 11.4%; P < 0.001), and hot air (24.2% vs. 13.6%; P = 0.024) were significantly higher in those with unexplained chronic cough than in patients with chronic cough. The most common trigger was cold air, reported by 75.2% of all patients, but the percentage did not differ significantly between the 2 patient groups (P = 0.45).

Table 3. Cough triggers in patients with chronic cough.

| Q. Do any of the following trigger your cough? | Total (n = 478) | Unexplained chronic cough (n = 62) | Chronic cough (n = 416) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold air (%) | 75.2 | 79.0 | 74.8 | 0.45 |

| Dry air (%) | 58.1 | 79.0 | 55.0 | < 0.001 |

| Sputum (%) | 54.1 | 61.3 | 53.0 | 0.22 |

| Smoke or smoky atmosphere (%) | 53.1 | 58.1 | 52.3 | 0.40 |

| Change in body position (%) | 44.0 | 53.2 | 42.6 | 0.12 |

| Talking (%) | 42.7 | 58.1 | 40.4 | 0.009 |

| Postnasal drip (%) | 33.7 | 12.9 | 36.8 | < 0.001 |

| Perfumes or scents (%) | 28.3 | 45.2 | 25.7 | 0.002 |

| Exercise (%) | 22.2 | 21.0 | 22.5 | 0.79 |

| Eating (%) | 20.3 | 53.2 | 15.3 | < 0.001 |

| Brushing teeth (%) | 16.4 | 24.2 | 15.3 | 0.076 |

| Damp conditions (%) | 16.2 | 16.1 | 16.2 | 0.99 |

| Heartburn (%) | 16.0 | 41.9 | 12.1 | < 0.001 |

| Laughing (%) | 15.8 | 17.7 | 15.5 | 0.65 |

| Indigestion (%) | 15.2 | 40.3 | 11.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hot air (%) | 14.7 | 24.2 | 13.6 | 0.024 |

| Total cough trigger score* | 5.3 ± 2.8 | 6.9 ± 2.6 | 5.0 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

*Total score indicates the sum of number of positive responses; †Difference between the unexplained chronic cough and chronic cough groups.

Linear regression analyses were performed to determine whether the associations between unexplained chronic cough and CHQ score were independent of demographic factors. Univariate analyses showed that younger age, female sex, and unexplained chronic cough were significantly correlated with CHQ score (Table 4). Multivariate analysis after adjustment for age, sex, smoking and cough duration showed that the correlation between CHQ score and unexplained chronic cough was statistically significant (regression coefficient, 2.64; 95% confidence interval, 1.49-3.78; P < 0.001; Table 4).

Table 4. Linear regression analyses for CHQ score in 478 patients with chronic cough.

| For CHQ score | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age | −0.06 (−0.08 to −0.03) | < 0.001 | −0.06 (−0.08 to −0.04) | < 0.001 | |

| Male sex | −1.16 (−1.94 to −0.38) | 0.004 | −1.08 (−2.02 to −0.15) | 0.022 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | |||

| Ex-smoker | −1.06 (−2.03 to −0.09) | 0.033 | −0.10 (−1.18 to 0.97) | 0.850 | |

| Current smoker | −0.79 (−2.18 to 0.59) | 0.259 | −0.34 (−1.83 to 1.14) | 0.650 | |

| Cough duration | |||||

| 2 to 6 months | Reference | Reference | |||

| 6 to 12 months | −0.45 (−1.57 to 0.66) | 0.425 | −0.40 (−1.48 to 0.68) | 0.465 | |

| 1 to 5 years | 0.67 (−0.29 to 1.63) | 0.171 | 0.09 (−0.90 to 1.07) | 0.865 | |

| > 5 years | −0.56 (−1.53 to 0.41) | 0.259 | −1.02 (−2.03 to −0.01) | 0.049 | |

| Unexplained chronic cough | 2.28 (1.21 to 3.34) | < 0.001 | 2.64 (1.49 to 3.78) | < 0.001 | |

CHQ, cough hypersensitivity questionnaire; CI, confidence interval.

*Adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, cough duration, and unexplained chronic cough group.

Correlations of CHQ with LCQ and cough VAS scores in unexplained chronic cough

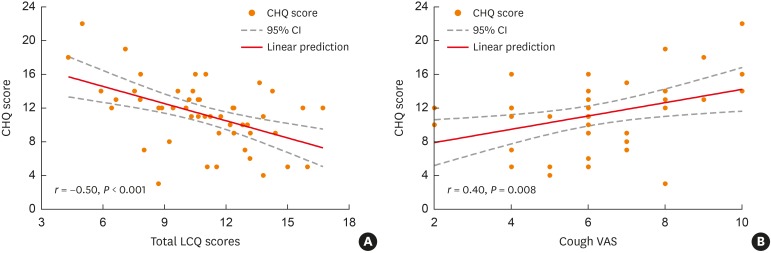

Further analyses were performed to determine whether CHQ score correlated with LCQ and cough VAS scores in patients with unexplained chronic cough. Mean LCQ and cough VAS scores were 10.7 ± 2.9 and 6.1 ± 2.0, respectively (Table 1). Total LCQ scores, however, did not differ according to age, sex, smoking history, or cough duration.

Spearman's correlation analyses showed that total CHQ score correlated significantly with total LCQ score (r = −0.50, P < 0.001; Fig. 2A) and cough VAS score (r = 0.40, P = 0.008; Fig. 2B). The number of positive laryngeal sensations was also positively correlated with LCQ (r = −0.51, P < 0.001) and cough VAS (r = 0.53, P = 0.001) scores (Supplementary Table S1). The number of positive cough triggers showed a significant correlation with LCQ score (r = −0.40, P = 0.005) but not with cough VAS score (r = 0.21, P = 0.171; Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Correlations of CHQ score with (A) LCQ, and (B) cough VAS scores in the unexplained chronic cough group.

CHQ, Cough Hypersensitivity Questionnaire; LCQ, Leicester Cough Questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue scale; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The present study used the CHQ to describe symptom profiles in adult patients with chronic cough as well as explored the clinical relevance of cough hypersensitivity in relation to cough impact and severity. We found that cough-related abnormal throat sensations and cough triggers are common both in unselected patients with chronic cough and in patients with unexplained chronic cough, indicating that hypertussia, allotussia, and laryngeal paresthesia are common features of chronic cough in adults. Subjects with unexplained chronic cough reported multiple laryngeal sensations and cough triggers, and the number of positive laryngeal sensations and cough triggers was significantly higher in this group than in patients newly referred for chronic cough. In addition, CHQ scores correlated significantly with LCQ and cough VAS scores. These findings collectively indicate that cough hypersensitivity is a common feature of chronic cough in adults and is likely to be more relevant to unexplained chronic cough.

A few previous studies have reported hypersensitivity symptom profiles and the clinical relevance in patients with chronic cough.10,11 A study of the frequency of laryngeal sensations and cough triggers and their tussigenic potency (calculated by asking participants whether the trigger exposure resulted in a cough) in 53 patients with chronic refractory cough in Australia found that about 94% of these patients reported abnormal sensations in the laryngeal area (described as blocked throat, pressure on the chest, tightness of the throat, or irritation).10 Most of these subjects reported a predominant pattern of non-tussive or mixed tussive and non-tussive triggers, with few reporting a tussive trigger pattern alone, suggesting a hypersensitive nature of chronic refractory cough.10 Meanwhile, a study of urge to cough and associated somatic sensations in 100 unselected patients with chronic cough attending a specialist clinic in UK found that 91% always cough in response to urge to cough and that the urge to cough was frequently associated with abnormal throat sensations such as irritation (86%) and tickling (73%).11 Talking (72%), cold temperatures (67%), and dry atmospheres (66%) were common triggers for their cough. Cluster analyses based on relieving and aggravating factors associated with urge to cough found that the cluster with more frequent cough triggers (67%) had a significantly higher percentage of women (77.6% vs. 56.3%; P = 0.029) and had greater impairment in the physical domain of the LCQ (3.8 vs. 5.1; P = 0.006), compared with the cluster with less frequent cough triggers.11 However, either study did not recruit comparison groups, limiting further interpretation of the clinical relevance.

Similar to these earlier studies,10,11 we found that abnormal laryngeal sensations and cough triggers are common in patients with chronic cough. A comparison of symptom profiles in newly referred patients and those with unexplained chronic cough showed that the features of cough hypersensitivity are more common in patients with unexplained chronic cough. In addition, we demonstrated that the degree of cough hypersensitivity, as measured by the CHQ, significantly correlates with LCQ and cough VAS scores, both of which are common clinical tools for assessing cough impact and severity in the practice and research.18

Interestingly, the CHQ analyses also showed that several specific sensations and triggers were more frequent in patients with unexplained chronic cough (Tables 2 and 3). However, as the control group (patients newly referred with chronic cough) was not characterized, longitudinal assessments are warranted to further interpret each finding. Because the CHQ evaluates the triggering potential of exposure to a specific stimulus, the high rates of heartburn do not indicate the comorbidity of untreated acid reflux. None of the subjects in the unexplained chronic cough group responded to treatment with proton pump inhibitors.

Meanwhile, the high rates of dryness-related cough (dry throat as a sensation and dry air as a cough trigger) in patients with unexplained chronic cough may have implications for clinical practice and research. Indeed, adequate hydration and avoidance of dehydrating substances (such as caffeine and alcohol) are among the main components of current non-pharmacological cough control therapy protocols.19,20 The mechanisms by which dry air triggers cough are still poorly understood; however, in a study of asthmatic patients, isocapnic dry air hyperpnea provoked cough within the first minute of inhalation, and the cough response to dry air challenge correlated significantly with hypertonic saline challenge (r = 0.59, P < 0.001), suggesting that dry air hyperpnea and hypertonicity as cough triggers have similar mechanisms of action.21

This study had several major limitations. First, it was cross-sectional in nature, suggesting the need for further longitudinal assessments to determine the relevance of the CHQ symptom profiles. Second, the control group of patients, consisting of those newly referred for chronic cough, were not fully phenotyped at the time of the survey. Thus, it remains to be eluciated whether cough hypersensitivity symptom profiles could differentiate phenotypes in chronic cough. To our knowledge, there is no report on the predictive value of cough triggers or laryngeal sensations. It is our speculation that these symptoms may not be specific for certain cough phenotypes such as upper airway diseases, asthma, eosinophilic bronchitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease, because most of items in the CHQ were more positive in the unexplained cough group than in the unselected chronic cough group. In our previous single center study, several indicators for cough hypersensitivity, including objective cough response to capsaicin inhalation, subjective cough sensitivity to cold air or singing/talking or abnormal laryngeal sensation, were not significantly associated with specific traits such as eosinophilic inflammation, airway hyper-responsiveness or nasal symptoms, but were only partially related to demographic factors such as age and sex.12 In the present study, we also found that older age and female sex were positively associated with CHQ scores (Table 4). Third, all patients were recruited from specialist clinics at tertiary hospitals. This may limit external validity of our findings to primary care population. About 75% of our study participants reported that they had previously visited 2 or more clinics for chronic cough. Thus, the group of newly referred patients may have included some patients refractory to conventional treatments. In our clinical experience, about 10%–20% of Korean patients attending referral clinics are refractory to conventional treatments. However, the possible inclusion of these patients likely did not influence the conclusions that cough hypersensitivity is likely to be more relevant to unexplained chronic cough, as their inclusion may have underestimated, but not over-estimated, the difference between groups. Fourth, use of the CHQ to assess cough-related sensations and cough triggers has not been formally validated, but is based only on pilot data from patients with idiopathic cough.14 Also, we relied on patient self-reporting to assess cough triggers, suggesting the need for objective challenge to quantify the triggering effects. However, the results of the present study suggest that assessment of cough hypersensitivity symptom profiles using the CHQ is likely to be clinically useful. Fifth, medication might also affect laryngeal sensation and trigger patterns. Sixth, we did not objectively measure cough frequency. Measurement of objective cough frequency would help to further understand the relevance of CHQ in chronic cough. Finally, the number of unexplained chronic cough patients was relatively small (n = 62 vs. 416), which may underpower the comparative analyses. However, this large difference is the result from consecutive recruitment, and it is in line with the prevalence of unexplained cough patients reported in the literature (10%–40% of overall patients).22

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggest that cough hypersensitivity may be a common feature in adult patients with chronic cough and is more relevant to unexplained chronic cough. Correlations of CHQ score with LCQ and cough VAS scores suggest the potential clinical relevance of assessing cough hypersensitivity in adult patients with chronic cough. Further validation and longitudinal studies are warranted to determine the relevance of the cough hypersensitivity profiles in relation to treatment response and cough phenotypes and to further understand the mechanisms underlying cough hypersensitivity in adults with chronic cough.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Correlations of CHQ score with LCQ and cough VAS scores in patients with unexplained chronic cough

References

- 1.Morice AH, Fontana GA, Sovijarvi AR, Pistolesi M, Chung KF, Widdicombe J, et al. The diagnosis and management of chronic cough. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:481–492. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00027804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, Boulet LP, Braman SS, Brightling CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:1S–23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, Kim JY, Kang MG, Kim S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1479–1481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French CL, Irwin RS, Curley FJ, Krikorian CJ. Impact of chronic cough on quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1657–1661. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, Kang MK, Kim JY, Kang MG, et al. Defining chronic cough: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8:146–155. doi: 10.4168/aair.2016.8.2.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KF. Approach to chronic cough: the neuropathic basis for cough hypersensitivity syndrome. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:S699–S707. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, Bieksiene K, Birring SS, Chung KF, et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1132–1148. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song WJ, Morice AH. Cough hypersensitivity syndrome: a few more steps forward. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:394–402. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.5.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung KF. Chronic ‘cough hypersensitivity syndrome’: a more precise label for chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vertigan AE, Gibson PG. Chronic refractory cough as a sensory neuropathy: evidence from a reinterpretation of cough triggers. J Voice. 2011;25:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton E, Marsden P, Thurston A, Kennedy S, Decalmer S, Smith JA. Clinical features of the urge-to-cough in patients with chronic cough. Respir Med. 2015;109:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song WJ, Kim JY, Jo EJ, Lee SE, Kim MH, Yang MS, et al. Capsaicin cough sensitivity is related to the older female predominant feature in chronic cough patients. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6:401–408. doi: 10.4168/aair.2014.6.5.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song DJ, Song WJ, Kwon JW, Kim GW, Kim MA, Kim MY, et al. KAAACI evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for chronic cough in adults and children in Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10:591–613. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La-Crette J, Lee KK, Chamberlain S, Saito J, Hull J, Chung KF, et al. The development of a Cough Hypersensitivity Questionnaire (CHQ) Thorax. 2012;67:A127 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha A, Lee KK, Rafferty GF, Yousaf N, Pavord ID, Galloway J, et al. Predictors of objective cough frequency in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1461–1471. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01369-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song WJ, Lee SH, Kang MG, Kim JY, Kim MY, Jo EJ, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey screening questionnaire for use in epidemiologic studies for adult asthma. Asia Pac Allergy. 2015;5:25–31. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon JW, Moon JY, Kim SH, Song WJ, Kim MH, Kang MG, et al. Reliability and validity of a Korean version of the Leicester Cough Questionnaire. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2015;7:230–233. doi: 10.4168/aair.2015.7.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birring SS, Spinou A. How best to measure cough clinically. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;22:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vertigan AE, Theodoros DG, Gibson PG, Winkworth AL. Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax. 2006;61:1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamberlain Mitchell SA, Garrod R, Clark L, Douiri A, Parker SM, Ellis J, et al. Physiotherapy, and speech and language therapy intervention for patients with refractory chronic cough: a multicentre randomised control trial. Thorax. 2017;72:129–136. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purokivi M, Koskela H, Brannan JD, Kontra K. Cough response to isocapnic hyperpnoea of dry air and hypertonic saline are interrelated. Cough. 2011;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGarvey L. The difficult-to-treat, therapy-resistant cough: why are current cough treatments not working and what can we do? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26:528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlations of CHQ score with LCQ and cough VAS scores in patients with unexplained chronic cough