Abstract

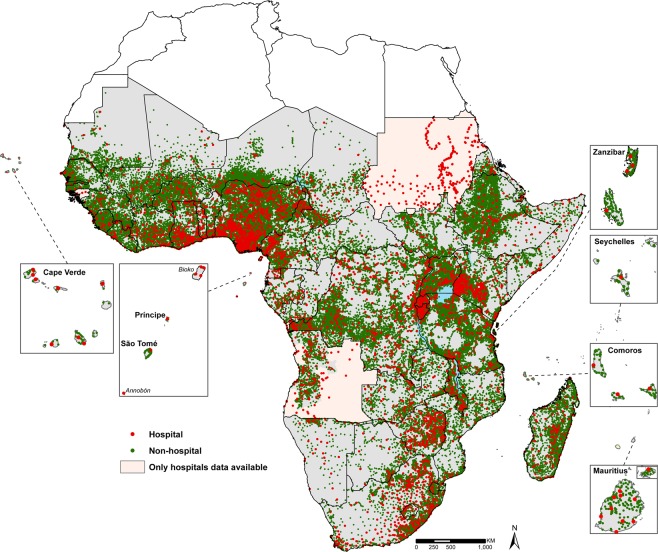

Health facilities form a central component of health systems, providing curative and preventative services and structured to allow referral through a pyramid of increasingly complex service provision. Access to health care is a complex and multidimensional concept, however, in its most narrow sense, it refers to geographic availability. Linking health facilities to populations has been a traditional per capita index of heath care coverage, however, with locations of health facilities and higher resolution population data, Geographic Information Systems allow for a more refined metric of health access, define geographic inequalities in service provision and inform planning. Maximizing the value of spatial heath access requires a complete census of providers and their locations. To-date there has not been a single, geo-referenced and comprehensive public health facility database for sub-Saharan Africa. We have assembled national master health facility lists from a variety of government and non-government sources from 50 countries and islands in sub Saharan Africa and used multiple geocoding methods to provide a comprehensive spatial inventory of 98,745 public health facilities.

Subject terms: Health services, Developing world, Geography

| Design Type(s) | data integration objective • database creation objective |

| Measurement Type(s) | Healthcare Facility |

| Technology Type(s) | digital curation |

| Factor Type(s) | geographic location • Facility • organization |

| Sample Characteristic(s) | Sub-Saharan Africa • public infrastructure |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Background and Summary

Defining the location of health services in relation to the communities they are intended to serve is the cornerstone of health system planning, ensuring the right services are accessible to the population and that no one is geographically marginalized from essential services. Across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), health services are offered with increasing levels of medical sophistication, from community providers who handle basic care to hospitals which play a critical role in providing emergency care1–3. However, these services are not accessible to everyone equally4. This inability to reach quality assured health services able to provide life-saving interventions contributes to the sustained high burden of communicable and non-communicable disease morbidity and mortality in SSA relative to other regions of the world5,6. The Global health agenda now aims to ensure Universal Health Coverage (UHC), to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need and underpins the health-related Sustainable Development Goals. Defining and planning for universal equity in access to health services demands better data on the location of both services and populations they are intended to serve.

While countries have been encouraged to develop health Master Facility Lists (MFLs)7,8 and censuses of service provision9, this has not been universal and most inventories lack coordinates. In Kenya in 2003, we began an exercise to compile and geocode a single, public health MFL from a variety of government, non-governmental (NGO), community-based (CBO) and faith-based organization (FBO) listings10, the first time a national map of service providers had been developed since 195911. Over the next 15 years we extended this approach across other countries in SSA, coinciding with a regional impetus to improve master health facility lists7,8.

Access to health care is a complex and multidimensional concept and can be defined in a variety of ways, however, in its most basic sense, it refers to geographic availability. Improved data metrics on health access demands at the very least a knowledge of where service providers are in relation to populations. Provider-to-population ratios were used to estimate availability in 1970s and earlier12–14, then the emergence of Geographic information systems (GIS) in 1980s and 1990s led to the evolution of distance as a metric15–17 while network analyses, floating catchment area methods and cost-distance analyses are more recent18–21. By identifying top tier hospitals and lower tier facilities, it is now possible to estimate specific access to emergency care and surgeries18,22–24. Other extensions are application in defining access to Basic and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC/EmONC) services25, evaluating public health sector service delivery26 and community-based interventions27–29. In the future, it is likely that this will be extended to understanding health care optimization. Georeferenced health service inventories, beyond defining equitable access, increase the epidemiological value of defining the evolution of emerging, epidemic pathogens30, antimicrobial resistance, and defining sub-national disease epidemiology as well as improving the potential of routine health data use31.

Notwithstanding previous efforts to extract health service providers from OpenStreetMap complimented by volunteered information (https://www.healthsites.io), there is no single, georeferenced and comprehensive public health facility inventory for sub-Saharan Africa. Building on a previous audit of public hospitals in sub Saharan Africa18, we provide a geo-coded inventory of 50 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, provided as an open-access resource. We have focused on public health facilities managed by government, local authorities, FBOs and NGOs. A wide variety of primary sources of information were consulted, from websites and data portals of ministries of health, national and international organizations, health sector reports, to sourcing data through personal communications. Facility types and numbers for each country were validated using reported data in national health sector strategic plans and other health sector reports.

Methods

Data sources

We undertook a data assembly process to compile a comprehensive health facility database across SSA, starting with Kenya in 200410,32, and expanding to the rest of SSA between 2012 and 2018. Country-specific public health facility databases were developed through a systematic and iterative process of data assembly from a variety of sources, data abstraction, geocoding and technical validation of the data. For each country, the Ministry of Health (MoH) website was the first source of authoritative MFLs consulted. This was done through online searches and downloads of MFLs or maps hosted on the MoH website or on data portals managed by the MoH such as the National Health Map (Carte Sanitaire), health facility registries and online Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) including District Health Information Systems version 2 (DHIS2). In some instances, MoH publications with information on facility lists or maps were used. Occasionally, while the MoH sources did not have comprehensive lists of facilities or maps, other government agencies’ websites, for example national statistical agencies, hosted health facility listings and these were consulted. Where the governmental ministries and agencies had no facility listing information or was inadequate, other sources of data were consulted, including data hosted by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (UNOCHA) Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) portal and websites of other UN agencies, and where relevant, websites of FBOs and NGOs working in each country. For countries where no health facility data were available online, we made attempts to directly contact people working with National Malaria Control Programmes, World Health Organization or other health-oriented agencies to aid in locating health facility listings. Often, more than one source of data was consulted for each country and assembled into a single list as illustrated in Online-only Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Online only Table 1.

Description of data sources, including personal communication, by country and year data acquired and total number of public health facilities assembled for each country. The data sources are listed chronologically with the main data sources listed first. Notes indicate details of the final state of the health facility list in each country after data cleaning, abstraction and geocoding.

| Country | Sources of database | Year | MFL available online & geocoded | MFL available online & not geocoded | Maps available online & digitized | Total number of health facilities assembled (% geocoded) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | • Personal communication | 2013 & 2017 | N | N | N | 1,575 (91) | Non-hospitals (Lower level facilities) data missing in 10 provinces; 140 missing coordinates |

| Benin |

• (https://docplayer.fr/75764654-Republique-du-benin-ministere-de-la-sante.html) • Personal communication |

2017 2014 |

N | N | Y | 819 (100) | |

| Botswana | • (http://www.gov.bw/en/Ministries–Authorities/Ministries/MinistryofHealth-MOH/About-MOH/About-MOH/) | 2015 | N | Y | N | 624 (96) | 22 missing coordinates |

| Burkina Faso |

• (http://www.cns.bf/IMG/pdf/carte_sanitaire_2010.pdf) • Personal communication |

2012 2012 |

N | N | Y | 1,721 (100) | |

| Burundi | • (https://insp.bi/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Rapport-FOSA-d%C3%A9finitif-final-23-01-2014.pdf) | 2016 | Y | N | N | 665 (100) | |

| Cameroon |

• (https://www.dhis-minsante-cm.org/portal/) • Personal communication |

2017 2014 |

N | N | Y | 3,061 (99) | 42 missing coordinates |

| Cape Verde |

2016 2016 |

N | N | Y | 66 (98) | 1 missing coordinate | |

| Central African Republic |

• (https://www.healthsites.io/) • Personal communication |

2018 2014 |

Y | N | N | 555 (98) | 10 missing coordinates |

| Chad |

• (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/chad-gis-geodatabase) • Personal communication |

2013 2016 2013 |

N | Y | N | 1,283 (96) | 54 missing coordinates |

| Comoros | • (https://docplayer.fr/29010911-Profil-du-systeme-de-sante.html) | 2016 | N | Y | N | 66 (98) | 1 missing coordinate |

| Congo | • Personal communication | 2014 | N | N | N | 328 (98) | 7 missing coordinates |

| Cote d’Ivoire |

• (http://www.synamepci.org/synamep/doc/CARTE_SANITAIRE/CARTE_SANITAIRE_2010_22.02.12.VF.pdf) • Personal communication |

2014 2014 |

N | N | Y | 1792 (99) | 25 missing coordinates |

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) |

• Personal communication • (https://web-archive.lshtm.ac.uk/www.linkmalaria.org/sites/link/files/content/country/profiles/DRC%20Final%20Report%20June%20(240614).pdf) • (http://www.finddiagnostics.org/programs/hat-ond/hat/health_facilities.html) |

2014, 2017, 2018 2014 2013 |

N | N | N | 14,586 (100) | |

| Djibouti |

• (http://www.sante.gouv.dj/Carte%20sanitaires.htm) • (http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17292e/s17292e.pdf) |

2012 2016 |

N | N | Y | 66 (98) | 1 missing coordinate |

| Equatorial Guinea | • Personal communication |

2017 2017 |

N | N | Y | 47 (100) | |

| Eritrea |

• (https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-05/eritrea-health-mdgs-report-2014.pdf) • Personal communication |

2014 2016 |

N | N | Y | 269 (100) | |

| eSwatini |

• (https://www.shbcare.org/docs/SAM.pdf) • Published paper31 • Personal communication |

2018 2014 2013 |

N | N | Y | 135 (98) | 3 missing coordinates |

| Ethiopia |

• Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency43 • (https://ideas.lshtm.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Berhanu_DIPH_Ethiopia_17Sept2013.pdf) |

2015 2015 |

N | N | Y | 5,215 (99) | 39 missing coordinates |

| Gabon |

• (http://csgabon.info/file/f2/Annuaire%20statistique%20sante%202011.pdf) • Personal communication |

2011 2013 |

N | N | Y | 542 (98) | 10 missing coordinates |

| Gambia | 2015 | N | Y | N | 103 (98) | 2 missing coordinates | |

| Ghana | (http://data.gov.gh/dataset/health-facilities) | 2017 | Y | N | N | 1,960 (96) | 82 missing coordinates |

| Guinea | (https://data.hdx.rwlabs.org/dataset/health-centers-data-base) | 2015 | Y | N | N | 1,746 (87) | 225 missing coordinates |

| Guinea-Bissau | • Google Earth44 | 2017 | N | N | Y | 8 (100) | Only hospitals data available |

| Kenya |

• (http://kmhfl.health.go.ke/) • (https://hiskenya.org/dhis-web-commons/security/login.action) |

2016 2016 2004, 2009 |

N | Y | N | 6,146 (98) | 102 missing coordinates |

| Lesotho |

• (http://www.chal.org.ls/hospitals.php) • (https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Lesotho-Health-Systems-Assessment-2010.pdf) |

2016 2016 |

N | Y | N | 117 (92) | 9 missing coordinates |

| Liberia |

• (https://data.hdx.rwlabs.org/dataset/health-facilities-liberia-oct-2014) |

2015 2016 |

Y | N | N | 740 (100) | |

| Madagascar | • Personal communication | 2012 | N | N | N | 2,677 (99) | 13 missing coordinates |

| Malawi |

• (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/malawi-health) • (http://www.cham.org.mw/uploads/7/3/0/8/73088105/cham_health_facilities_-_1_june_2016.pdf) • Personal communication |

2017 2016 2013 |

Y | N | N | 648 (99) | 9 missing coordinates |

| Mali |

• (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/mali-healthsites) • (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/mali-healthsites/resource/e152bb47-e14c-471c-b47d-0cc93da531db) • (http://www.washclustermali.org/sites/default/files/micro-coordination_wash_dans_cscoms_et_csrefs_19-02-2013.xls) |

2017 2016 2017 |

Y | N | N | 1478 (98) | 30 missing coordinates |

| Mauritania | • (http://cartesanitairemauritanie.blogspot.com/) | 2017 | N | N | Y | 645 (100) | 50 missing facility names |

| Mauritius | • (http://health.govmu.org/English/Pages/default.aspx) | 2018 | N | N | Y | 166 (100) | |

| Mozambique |

• (http://sis-ma.in/?page_id=740) • Personal communication |

2017 2013 |

Y | N | N | 1,579 (100) | |

| Namibia | • (https://mfl.mhss.gov.na/location-manager/locations) | 2018 | Y | N | N | 369 (97) | 10 clinics missing coordinates |

| Niger |

• (http://www.who.int/hac/crises/ner/maps/ne_poster.jpg?ua=1) • Personal communication |

2017 2013 |

N | N | Y | 2,886 (98) | 46 missing coordinates |

| Nigeria |

• (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/nigeria-healthsites) • Personal communication |

2016 2012 |

Y | N | N | 20,807 (95) | 1,114 missing coordinates |

| Rwanda |

• Personal communication |

2017 2014 |

Y | N | N | 572 (100) | |

| São Tomé & Príncipe | • (https://repositorio.hff.min-saude.pt/bitstream/10400.10/440/1/Apresentacao%201.pdf) | 2016 | N | N | Y | 50 (100) | Facility names missing except for hospitals |

| Senegal |

• (http://www.sante.gouv.sn/ckfinder/userfiles/files/cartesanonze.pdf) • Personal communication |

2017 2015 |

N | Y | N | 1,347 (93) | 91 missing coordinates |

| Seychelles | • (https://www.seychellespromo.com/guide/Medical) | 2018 | N | Y | N | 18 (100) | |

| Sierra Leone | • (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/health-facilities-in-guinea-liberia-mali-and-sierra-leone/resource/816718bb-4929-49f0-854d-85b24a0bdb69) | 2017 | Y | N | N | 1,120 (100) | |

| Somalia |

• (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/somalia-health-facilities)(https://reliefweb.int/map/somalia/somalia-functioning-health-facilities-april-june-2013) • UNICEF & WHO report45 |

2016 2013 2013 |

Y | N | N | 879 (96) | 39 missing coordinates |

| South Africa |

• (https://dd.dhmis.org/orgunits.html?file=NIDS%20Integrated&source=nids) • Personal communication |

2017 2017 |

Y | N | N | 4,303 (99) | 15 missing coordinates |

| South Sudan | • (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/south-sudan-health) | 2017 | Y | N | N | 1,747 (99) | 13 missing coordinates |

| Sudan | • Personal communication | 2016 | N | N | N | 272 (96) | Only hospitals data available; 10 missing coordinates |

| Tanzania (mainland) | • (http://hfrportal.ehealth.go.tz/index.php?r=facilities/facilitiesList) | 2018 | Y | N | N | 6,304 (100) | |

| Togo |

• (www.stat-togo.org/nada/index.php/catalog/29/download/990) |

2017 2017 |

N | Y | N | 207 (85) | 31 missing coordinates |

| Uganda |

• (http://library.health.go.ug/publications/health-infrastructure-physical-infrastructure/health-facility-inventory) • Personal communication |

2018 2017 |

N | Y | N | 3,792 (97) | 115 missing coordinates |

| Zambia |

• (http://www.moh.gov.zm/docs/facilities.pdf) • Personal communication |

2017 2012 |

N | Y | N | 1,263 (99) | 4 missing coordinates |

| Zanzibar |

• (https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjNrNDQ7cXiAhURzoUKHRsRCm8QFjAAegQIBBAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Ftanzania.um.dk%2F~%2Fmedia%2FTanzania%2FDocuments%2FHealth%2FZanzibar%2520Strategic%2520Plan%252014%2520-%252018.pdf%3Fla%3Den&usg=AOvVaw3VMLPmQGTMK3Ftm02R_NqP) • Personal communication |

2013 2013 |

N | N | Y | 145 (100) | |

| Zimbabwe |

2016 2017 2017 |

Y | N | N | 1,236 (97) | 35 missing coordinates |

Note: Abbreviations MFL - Master Facility List; INGO - Inter-Governmental Organization; WHO - World Health Organization; UNOCHA HDX- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Data Exchange; HMIS - Health Management Information System; UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

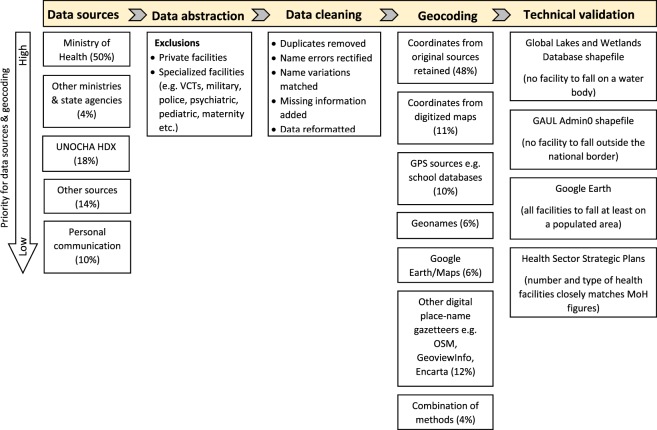

Fig. 1.

The methodological framework applied in assembling each country’s Master Facility List. Percentages for “Data sources” refer to proportion of the 50 countries with that source as the main or only source of data, while percentages under “Geocoding” refer to the proportion of all 98,745 health facilities.

Locations of existing health facility data for sub-Saharan African countries are fragmented. Half of the 50 countries had an MoH website/HMIS/data portal as the main source of data used; 4 (8%) had other governmental bodies, mainly national statistical agencies, as the main data source; 9 (18%) countries had UNOCHA HDX as the main data source, while we used other sources like NGO and FBO websites for 7 (14%) countries. The main source of data for the remaining 5 countries (10%) is unpublished data obtained through personal communication. In total, 93 different sources of data were consulted to develop the first sub-Saharan Africa geocoded inventory of health service providers across all levels of service provision (Online-only Table 1).

We have classified the 50 countries into 4 broad categories according to each country’s main source of health facility data consulted (Online-only Table 1). We have treated Zanzibar as a separate entity from mainland Tanzania as it has a separate health system. The first category includes 17 countries (Burundi, Central African Republic, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania and Zimbabwe) that have an online list of health facilities and for which data are available either fully or near fully geocoded. The second category includes 11 countries (Botswana, Chad, Comoros, Gambia, Kenya, Lesotho, Senegal, Seychelles, Togo, Uganda and Zambia) that had MFLs available online but lacked coordinates and where a process of geocoding was undertaken. The third category includes 17 countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, eSwatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Mauritius, Niger, São Tomé & Príncipe and Zanzibar) that had maps available online where a facility list was created through a process of onscreen digitization of locations in a GIS platform. The fourth category are 5 countries (Angola, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar and Sudan) where adequate data were not available online, and for which we relied on personal communication and in country contacts to acquire these data. We could not locate data for lower tier facilities for Guinea-Bissau and Sudan, and for 10 provinces in Angola (Online-only Table 1).

Data abstraction

Broadly, there are two main categories of health care delivery systems across sub-Saharan Africa - public and private. Private includes private-not-for-profit and private-for-profit33. We have focused on the public and private-not-for-profit sectors where health facilities are managed by the MoH, local authorities, NGOs, FBOs and CBOs. Private health facilities, though important in extending provision of health services, were excluded as previous audits of MFLs reveal that private sector facilities are often under-represented in MoH registries, located in urban centres, accessible only to those able to afford services, unregulated and do not often feature in MoH commodity distribution systems17. Their exclusion was a pragmatic decision based on difficulties with enumeration within the private sector10,32 and the complexity of its structural and organizational system34–37. Enumerating and regulating this sector has remained a challenge in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The private sector was difficult to audit despite extensive searches from multiple sources, where available, completeness varied wildly from country to country, and most of the facilities were often based in large cities and smaller urban areas. Our focus, therefore, has been on providers of public health sector services that cover services including expanded immunization programmes, health data surveillance and receive government funding to provide services to the general population. We have made a single exception to this rule, in Botswana, where many private company-owned health service providers also provide care to the general public and are more formally integrated into the government health system38. Across all countries, we excluded government facilities serving special groups, for example prisons, armed services, police, schools, universities and government service clinics. These services are often not available to the general population. Further exclusions were made to remove specialized care service providers such as blood transfusion centres, HIV Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) centres, maternity and nursing homes, family planning clinics and specialist facilities (e.g. dental, eye, psychiatric, tuberculosis, rehabilitation, ophthalmic) (Fig. 1). The spatial location of these services is equally important for health system planning but were not universally documented across national health facility listings. Our ambition was to provide a geo-coded inventory of operational facilities providing broad clinical care services to the general population. It was notable across several data sources that not all facilities were deemed operational, and those labelled as “under construction” or “closed” were excluded. In total, 98,745 public health facilities were assembled for 50 countries in sub Saharan Africa.

Data cleaning

From all sources a single set of minimal descriptive data was possible for each facility: first level administrative unit, facility name, facility type, and details on facility ownership. A common feature across all databases was the presence of duplicates and these were identified by a careful review of each country’s list and where identified were discarded. For facilities without names, we adopted names of the smallest administrative units i.e. wards, towns or villages, in which they are located if these were included in the original lists, with the assumption being that it is likely that a public facility has same naming orientation as the ward, town or village its located in. For those without names and information on admin units but with coordinates, we adopted the name of the nearest populated place based on calculated relative distances. In instances where information on facility ownership was missing an attempt was made to assign ownership based on the facility name e.g. all facilities that had a Christian name or church name such as Saint, protestant, mission, evangelical or Islamic were assigned FBO ownership, facility names with NGO names were classified as NGO-owned while the rest were assigned government ownership.

The size and definition of level of health facilities varied considerably within and between countries (Online-only Table 1). There doesn’t exists a universal standardized definition of facility types making cross country comparisons difficult, and definitions provided in national health policies varied between countries hence while we are relatively confident in the hospital definition used here, the definition for subsequent tiers were harder to reconcile between countries. We have therefore elected to include the information as shown in primary data sources consulted (Online-only Table 2).

Online-only Table 2.

Country-specific current Health Sector Strategic Plans (HSSPs) used to validate the number of health facilities in each country, while health sector reports, including the HSSPs, were used to validate the distribution of the health facility types across the health service delivery levels.

| Country (Sources of database) |

Services at healthcare delivery levels | Database | HSSP No. of facilities |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Angola |

I. Primary/municipal: District/Municipal Hospitals and Local Health Centres offer emergency, outpatient, antenatal, nursing, maternity, EPI, surveillance and testing of HIV and support. Health Post I and Health Post II facilities are first point of contact for the health system and provide basic outpatient services |

• 1152 Posto de Saude • 3 Centro Sanatorio Materno Infantil • 39 Centro Materno Infantil • 231 Centro de Saude • 100 Municipal Hospitals • 32 Hospitals |

• 1505 Health Posts • 332 Health Centers • 40 Maternal-Infant Centers • 155 Municipal Hospitals |

| I. Secondary/provincial: Provincial/General Hospitals offer specialized services and receive patients referred from primary level facilities |

• 11 Provincial hospitals • 3 General Hospitals • 1 Regional Hospital |

NR | |

| II. Tertiary/central: Teaching Hospitals and National Specialized Hospitals are the highest referral level and offer specialized care and training of medical professionals | • 3 Central Hospitals | • 3 Central Hospitals | |

|

Benin (https://www.urc-chs.com/sites/default/files/Benin_Pilot_Test_Assessment_Report.pdf) |

I. Peripheral: First level services offering curative, preventive, promotional and rehabilitation services. Village Health Units are first point of care; the second level is the health centre categorized as either Commune Health Centre or Arrondissement Health Centre. The Zonal Hospital is the first referral level for specialist care |

• 9 Unites de sante de village • 4 Clinique • 132 Centre Communal de Santé • 27 Dispensaire • 306 Centre de Santé d’Arrondissement • 8 Centre de Santé de Sous-Prefecture • 3 Centre Médico-Social • 24 Centre Medical • 1 Centro de Sante de Circonscription Urbaine • 246 Centre de Santé • 11 Centre de Santé Central • 20 Other Hôpitals • 21 Hôpitals de Zone |

• 425 Centre de Santé d’Arrondissement • 75 Centre de Santé de Commune • 27 Hôpitals de Zone |

| II. Intermediate: Departmental Referral Hospitals are the second referral facilities | • 5 Centre Hospitalier Départemental | • 5 Centre Hospitalier Départemental | |

| III. Central: The National University Hospital Centre (CNHU) is the national referral facility, providing highly specialized services and serves as a training centre | • 1 Centre National Hospitalier Universitaire | • 1 Centre National Hospitalier Universitaire | |

|

Botswana |

I. Primary: Health posts and mobile stops are first point of care to the national system and offer mainly outpatient care. Mobile stops are operated by clinics, do not have permanent structure and mainly offer promotive and preventive services. Clinics offer primary health care and outpatient services including general consultations, treatment of injuries and minor illnesses |

• 331 Health Posts • 264 Clinics |

NR |

| II. Secondary: Primary Hospitals are general hospitals that are equipped to deal with most diseases, injuries & immediate threats to health. District Hospitals in addition to primary care, offer intensive and pediatric care; Emergency services, surgery and intensive care; x-ray and diagnosis, dental care services; eye care services, orthopedic services |

• 17 Primary Hospitals • 10 District Hospitals |

• 16 Primary Hospitals • 12 District Hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: Referral Hospitals are equipped to handle complex diseases referred from lower level facilities | • 2 Referral Hospitals | ||

|

Burkina Faso46 (https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2018-08/Profil%20sanitaire%20du%20Burkina%20%202.pdf) |

I. Primary (level 1): first point of entry to the health system. Health posts provide general out-patient care for infectious diseases and minor injuries performed by voluntary CHWs. Community health and welfare promotion centres (CSPS) provide promotional, preventive, and curative care, antenatal care services, out-patient management, EPI, counseling, family planning, and social mobilization |

• 81 Dispensaries • 1537 Community Health and Welfare Promotion Centres |

NR |

| II. Primary (level 2): Centre Médical (CM) and Centre Médical avec Antenne Chirurgicale (CMA) offer first level referral care and surgical services |

• 41 Medical Centres (CM) • 49 Centre Médical avec Antenne Chirurgicale (CMA) |

• 42 Centre Médical avec Antenne Chirurgicale (CMA) | |

| III. Secondary (level 3): Regional Hospitals offer complex services referred from primary hospitals | • 9 Regional Hospitals | • 6 Regional Hospitals | |

| IV. Tertiary (level 4): National and Teaching Hospitals provide all services at lower levels in addition to offering training and research facilities |

• 3 University Hospital Centres • 1 National Hospital |

• 1 National Hospital | |

|

Burundi47 |

I. Peripheral: Health Centres offers a minimum package of services, including treatment and prevention, consultation, laboratory, pharmacy, health promotion and health education services, and in-patient observation. District Hospitals are first referral facilities. |

• 616 Health Centres • 46 District Hospitals |

• 897 Health Centres • 69 Hospitalsa |

| II. Intermediate: Regional Hospitals offer specialized psychiatric services, including medication and psycho-education | NR | ||

| III. Central: Specialized Hospitals, National Hospitals and the University Hospital are the highest referral centres and provide highly specialized services and referrals from all other facilities countrywide | • 3 Tertiary Hospitals | ||

|

Cameroon48 (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/cameroon/cameroon_-_sss_validee_par_le_ccss_5_janvier.pdf) (http://www.statistics-cameroon.org/downloads/pets/2/Rapport_principal_Sante_anglais.pdf) |

I. Peripheral: Sub-divisional Medical Centres (CMA), Health Centres (CS & CSI) and Dispensaries offer minimum services including preventive and curative services and health promotion activities. Serious cases are referred to District Hospitals which are the first point of referral care |

• 223 Centre Medical d’Arrondissement • 362 Centre de Sante • 2241 Centre de Sante Integre • 48 Dispensaire • 3 Clinics • 165 District Hospitals |

• 3786 Centre de Sante Integre & Centre Medical d’Arrondissement • 218 District Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate: Regional Hospitals and General Hospitals offer specialized healthcare services including inpatient care |

• 14 Regional Hospitals • 3 General Hospitals |

• 15 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central: General Referral Hospitals, University Hospital Centres and Central Hospitals offers surgical care, obstetrics, gynaecology, radiology, intensive care, emergency and outpatient services. They serve as research and surveillance centres | • 2 Central Hospitals | • 15 General & Central Hospitals | |

|

Cape Verde |

I. Primary/municipal: Basic Health Units (Unidades Sanitárias de Base (USB), Health Posts (Postos de Saúde (PS) and Health Centres (Centros de Saúde (CS) are all first point of care and provde basic preventive and curative services |

• 26 Health Posts • 31 Health Centres |

• 113 Basic Health Units • 34 Health Posts • 30 Health Centres • 1 Polyclinic |

| II. Secondary/regional: Regional Hospitals (Hospitais Regionais (HR) provide care for cases of lesser complexity referred from health centres | • 7 Regional Hospitals | • 3 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Tertiary/central: National Reference Hospitals/Central Hospitals (Hospitais Centrais (HC) provides highly specialized care for complex medical cases referred from lower health facilities | • 2 Central Hospitals | • 2 Central Hospitals | |

|

Central African Republic (https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/Health_Provision_in_the_Central_African_Republic_latest_draft.pdf) Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population [Central African Republic]. Politique Nationale De Lutte Contre La Lepre. Bangui, Julliet 2007. (2007) - Document no longer vailable online. |

I. Peripheral: Prefectural/District Hospitals, Health Centre and Health Posts are first point of care providing promotional, preventive, and curative services |

• 326 Poste de santé • 44 Centre de Santé “A” • 45 Centre de Santé “B” • 57 Centre de Santé “C” • 2 Centre de Santé “D” • 61 Centre de Santé “E” • 12 Prefectural Hospitals |

• 445 Health Posts • 31 Health Centres “A” • 22 Health Centres “B” • 104 Health Centres “C” • 11 Health Centres “D” • 13 Health Centres “E” • 13 Prefectural Hospitals |

| II. Regional: Regional University Hospitals are stand‐alone facilities that offer specialised services for patients referred from prefectural hospitals | • 5 Regional University Hospitals | • 5 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central: Central Hospitals (Hôpital Centraux) are the highest referral facilities and offer specialized care including training | • 3 Central Hospitals | • 4 Central Hospitals | |

|

Chad49 (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Chad/plan_national_de_developpement_sanitaire_ii_2013-2015.pdf) |

I. Peripheral: Health Centres are the lowest level of primary health service. They are the first point of contact with health service and provide basic and primary health care | • 1205 Health Centres | • 1028 Health Centres |

| II. Districts: District Hospitals are first level referral hospitals equipped to handle special cases including maternal and child health | • 70 District Hospitals | • 72 District Hospitals | |

| III. Regional: National Referral Hospitals are tertiary level hospitals which are well equipped to offer specialized care and tertiary education |

• 7 Regional Hospitals • 1 National Hospital |

• 8 Regional Hospitals • 1 National Hospital |

|

|

Comoros (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Comoros/pnds_05_mai_2010_documentvf_en.pdf) |

I. Health District: District Health Centres and Health Posts (HP) offer primary care to the community |

• 1 Dispensaire • 45 Poste de Santé • 12 Centre de Santé • 3 Centre Médico-Urbain • 2 Centre Médico-Chirurgical |

• 4 NGO facilities • 52 Health Posts • 3 Centre Médico-Urbain • 2 Centre Médico-Chirurgical • 12 District Health Centres |

| II. Island/regional: Each island has a Regional Hospital (CHR) except the island of Ngazidja where the reference is the National Hospital | • 2 Regional Hospitals | • 2 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central: National Hospital (CHN) serve as highest referral facilities for specialized care | • 1 National Hospital | • 1 National Hospital | |

|

Congo (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Congo/ppac_2012-2016_congo.pdf) |

I. Peripheral: Hôpitaux de base, Centre de santé intégré (CSI), Centre de Traitement Ambulatoire (CTA), Centre de Dépistage et de Traitement (CDT) and other specialized treatment centres |

• 302 Centre de Santé Intégré • 10 Base Hospitals • 9 Comboutique Hospitals • 2 Hospitals |

• 12 Clinics • 16 Base Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate: Hôpitaux Généraux | • 4 General Hospitals | • 5 General Hospitals | |

| III. Central: Specialist Facilities and Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire (CHU) | • 1 University Hospital Centre | • 1 University Hospital | |

|

Cote d’Ivoire50 (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/cote_divoire/pnds_2016-2020.pdf) (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Cote%20DIvoire/psn_2011-2015_vih_sida.pdf) |

I. Peripheral/Operational: Rural Health Centres (CSR) are the first point of contact offering basic out-patient, promotional, preventive and maternity services. Urban Health Centres (CSU) offer all services by CSRs in addition to specialized treatment such as for HIV and TB. General Hospitals are the first referral centres |

• 1330 Rural Health Centres • 329 Urban Health Centres • 33 Medical Centres • 77 General Hospitals |

• 1237 Rural Health Centres • 514 Urban Health Centres • 66 General Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate/Regional: Regional Hospitals and Specialized Hospitals receive referrals from general hospitals and offer services such as general medicine, pediatrics and obstetrics | • 19 Regional Hospitals | • 17 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central: Teaching Hospitals (CHU) & National specialized care institutes offer medical training and national referral services | • 4 University Hospitals | • 4 University Hospitals | |

|

DRC (https://www.medbox.org/national-policy-project-fighting-to- malaria- download.pdf) |

I. Peripheral/health zone: Government Health Centres (HC) provide primary care services. General Referral Hospitals are the first level of referral services |

• 177 Clinique • 132 Dispensaire • 4231 Poste de Santé • 8,512 Centre de Santé • 160 Centre de Santé de Référence • 4 Centre de Santé Municipal • 98 Polyclinique • 834 Centre Médical • 3 Centre Medico-Chirurgical • 5 Hôpital Secondaire • 370 Hôpital Général de Référence |

• 8266 Health Centres • 393 General Referral Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate/provincial: Provincial Hospitals are the secondary referral facilities |

• 302 Hôpital • 72 Centre Hôpitalier |

• 6 Provincial Hospitals | |

| III. Central: National Hospitals and Reference Centres offer specialized services and training | • 3 Hospitalier Universitaire | • 3 University Hospitals | |

|

Djibouti (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Djibouti/pnds_2013_2017_partie_2_version_du_80113.pdf) (https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/76658/80917/F1028108119/DJI-76658.pdf) |

I. Primary: Health posts and Community Health Centres provide basic curative and preventive care, local health promotion & education & ensures community health support. Health Centres supervise the health posts and refer complex cases to District Hospitals. Intermediate Health Centres offer both outpatient and inpatient care |

• 41 Health Posts • 12 Community Health Centres |

NR |

| II. Secondary: The Regional Hospital is a second-level health facility. It supports referrals from health posts and Intermediate Health Centres. It offers all services provided by level 1 and additional health services such: medicine, pediatrics, routine surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency and ambulatory services, dental and ophthalmic care | • 5 Hospital Medical Centres | • 5 Medical Centres (District & Regional Hospitals) | |

| III. Tertiary: National Referral Hospitals and Special Facilities. They have a national scope, provide highly skilled care and undertake research and training | • 8 Tertiary Hospitals | • 4 Tertiary Hospitals | |

|

Equatorial Guinea (http://www.aho.afro.who.int/profiles_information/index.php/Equatorial_Guinea:Index) Ministere de la Sante et du Bienêtre Social [Equatorial Guinea]. Initiative Faire Reculer le Paludisme Plan Strategique 2009-2013. (2008) - Document no longer vailable online. |

I. Peripheral/operational: Health Posts and Health Centres are first point of care and provide basic routine outpatient services. District Hospitals provide more comprehensive care for referrals from health posts and health centres |

• 29 Health Centres • 11 District Hospitals |

• 161 health posts • 42 health centresb |

| II. Intermediate/regional: Provincial Hospitals | • 5 Provincial Hospitals | • 5 Provincial Hospitals | |

| III. Central: Regional Hospitals | • 2 Regional Hospitals | • 2 Regional Hospitals | |

|

Eritrea (http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/461991468770937666/pdf/297930PAPER000182131587616.pdf) National Malaria Control Program [Eritrea]. Malaria Five-Year Strategic Plan (2015-2019). Ministry of Health, Department of Public Health Communicable Diseases Control Division. (2014) - Document no longer vailable online. |

I. Primary: Community-based health services and Health Stations provide Basic Health Care Package (BHCP) based services by empowering communities, mobilizing and maximizing resources. Community Hospital is the referral facility for the primary health care level in addition to primary care, they offer obstetric and general surgical services |

• 2 Mini Clinic • 6 Clinics • 186 Health Stations • 53 Health Centres • 5 Mini Hospitals |

• 184 Health Stations • 52 Health Centres |

| II. Secondary: Regional (Zoba) Referral Hospitals and Sub-Zoba Hospitals serve as referral facilities for the lower level facilities, act as training institutions and provide facilities for research. Provide general surgery, deliveries, laboratory, ophthalmic care, radiology, dental, obstetric, and gynecological services | • 16 Hospitals |

• 13 Community Hospitals • 6 Zonal Referral Hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: National Referral Hospitals. Serves as centre of excellence for specialised training/education and research | • 1 National Referral Hospital | • 5 National Referral Hospitals | |

|

Ethiopia |

I. District: satellite Health Posts and Health Centres provide primary care services. Health centres also serve as a first curative referral centre for Health Posts. Primary Hospitals offer referral care from health posts and health centres |

• 3135 Clinics • 1002 Health Posts • 769 Health Centres • 10 Nucleas Health Centres • 138 Health Stations • 144 Hospitals • 5 District Hospitals |

• 16,440 Health Posts • 3,547 Health Centres |

| II. Regional: General Hospitals provides training, inpatient and ambulatory services and serves as a referral Centre for primary hospitals. |

• 3 Zonal Hospitals • 4 General Hospitals |

• 311 Hospitalsc | |

| III. National: Referral & Specialized Hospitals Handle more complicated and sophisticated health care, including the clinical management of non-communicable diseases. |

• 4 Referral Hospitals • 1 National Hospital |

||

|

Gabon |

I. Operational: Health Centres, Dispensaries and Health Posts are first level of the health pyramid and offers first point of care including primary care. Medical Centres serve as the reference level for lower level facilities. |

• 387 Dispensaires • 92 Centres de Santé • 4 Centres de Santé Urbain • 43 Centres Médical |

• 157 Health Huts • 413 Dispensaries • 34 Health Centers • 47 Departmental Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate/technical support: Regional Hospitals are referral facilities for the operational level and offer research operations and training |

• 1 Centre Hospitalier Urbain • 10 Hospitalier Régional |

• 9 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central/strategic: National, Psychiatric & Specialized Hospitals – highest referral facilities at national level and offer specialized care |

• 3 Hôpital Coopération • 2 Centre Hospitalier Universitaire |

• 4 University Hospitals | |

|

Gambia |

I. Clinics and Minor Health Centres: are often the first point of care and includes treatment of minor illnesses and referrals, environmental health & sanitation, antenatal, delivery and postpartum care, home visits & community health promotion | • 46 Clinics |

• 634 Primary Health Villages • 40 Community Clinics |

| II. Secondary: Minor Health Centres provide Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) services, nutrition services, control of common endemic diseases, Family Planning (FP) services, Health promotion and protection and provision of essential drugs and vaccines. Major Health Centres serve as referral points for minor health Centres in addition to offering minor surgeries, radiology and laboratory services |

• 44 Health Centres (minor) • 7 Health Centres (major) |

• 41 Minor Health Centres • 6 Major Health Centres |

|

| III. Tertiary: Regional Hospitals offer specialist care and referral services including dental and eye care services, laboratory and radiology services. Teaching Hospitals offer all services provided at regional hospital level, specialist hospital, services, and mortuary services |

• 3 Hospitals • 2 General Hospitals • 1 Teaching Hospital |

• 7 Tertiary Hospitals | |

|

Ghana51 (https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjyvqfPt8_iAhVJURoKHfehAV8QFjAAegQIAxAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fapps.who.int%2Fhealthinfo%2Fsystems%2Fdatacatalog%2Findex.php%2Fcatalog%2F21%2Fdownload%2F88&usg=AOvVaw2fz26L9PKg_VQty4Tfx-BP) (https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1093121/90_1236873017_accord-health-care-in-ghana-20090312.pdf) (https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/downloads/FACTS+FIGURES_2017.pdf) |

I. Community: Village or Community Health Posts provide preventive and primary health care services. | • 632 Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) | • 4185 Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) zones |

| II. Sub District: Health Centres and Clinics provide basic curative care, disease prevention and maternity services |

• 398 clinics • 740 Health Centres • 12 polyclinics |

• 1003 Clinics • 855 Health Centres • 34 Polyclinics |

|

| III. District: District Hospitals provide support to sub-districts in disease prevention and control, health promotion, referral outpatient and inpatient care, training and supervision, maternity services, management of complications, emergency services, and surgical care. |

• 77 Hospitals • 81 District Hospitals • 6 Municipal Hospitals |

• 137 District Hospitals • 267 Hospitals |

|

| IV. Regional: Regional Hospitals and polyclinics provide specialized clinical and diagnostic care, management of high-risk pregnancies and complications of pregnancy, technical and logistical back up for epidemiological surveillance, medical research and training of medical personnel. The polyclinics also serve as first point of contact in urban centres and therefore provide a mixture of preventive and curative care and use the regional hospitals for referrals |

• 3 General Hospitals • 8 Regional Hospitals |

||

| V. Tertiary: Teaching Hospitals offer specialized clinical and maternity services, undertake research, and provide highest level of undergraduate and postgraduate training in health and allied areas. | • 3 Teaching Hospitals | ||

|

Guinea (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Guinea/plan_national_developpement_sanitaire_2015-2024_guinee_fin.pdf) |

I. Primary/health district: Health Posts provide basic primary care. Health Centres provide preventive and curative care and supervise the health posts. District Hospitals serve as a reference for health Centres |

• 1241 Poste de Sante • 470 Centre de Sante • 25 Hopital Prefectoral |

• 925 Health Posts • 410 Health Centers • 5 Improved Health Centers • 33 Communal Medical Centers & Prefectural Hospitals |

| II. Secondary/regional: Regional Hospitals serve as a reference for the districts and receive referrals from district hospitals | • 7 Hopital Regional | • 7 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Tertiary/national: University Hospitals are the highest level of reference for specialized care | • 3 National Hospitals | • 3 National Hospitals | |

|

Guinea-Bissau (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Guinea-Bissau/pndsii_2008-2017_gb.pdf) |

I. Local/health areas: Basic Health Units are supported by CHWs and traditional midwives. Health Centres are classified as A, B and C which differentiates them, for example, surgery is provided at health Centres A. Health Centres can also be classified as rural or urban and their coverage area is extended by mobile teams. This level also consists of Sectoral Hospitals | • 4 Hospitals | NR |

| II. Regional: Regional Hospitals | • 3 Regional Hospitals | • 5 regional hospitals | |

| III. Central: National Hospital (National Simão Mendes Hospital (HNSM)) and Specialized Reference Centres | • 1 National Hospital | • 1 National Hospital | |

|

Kenya (http://publications.universalhealth2030.org/uploads/kenya_health_policy_2014_to_2030.pdf) (https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Lesotho-Health-Systems-Assessment-2010.pdf) |

I. Community level: provide health promotion services, and supply services. In the essential package, all Non-Facility Based Health and Related Services are classified as community services – not only the interventions provided through the Community Health Strategy as defined in NHSSP II | ||

| II. Dispensaries are at the lowest level of the public health system and are the first point of contact with patients. |

• 348 Clinics • 4352 Dispensaries |

• 169 Clinics • 3715 Dispensaries |

|

| III. Health Centres offer basic curative and preventive services, reproductive health, minor surgical services, outreach services, | • 1044 Health Centres | • 872 Health Centres | |

| IV. Primary referral facilities: District Hospitals receive referrals from primary care facilities and offer inpatient services, surgery and obstetrics. |

• 19 Hospitals • 89 Mission Hospitals • 158 Sub-District Hospitals • 121 District Hospitals |

• 347 County Hospitals | |

| V. Secondary referral facilities: Provincial Hospitals Offer specialized services such as pediatrics, surgery and serve as teaching centres given the availability of specialized staff. |

• 3 County Referral Hospitals • 10 Provincial General Hospitals |

• 7 Provincial General Hospitals | |

| VI. Tertiary referral facilities: National Teaching and Referral Hospitals are the referral centres of excellence and providing complex health services requiring more complex technology and highly skilled personnel | • 2 National Referral Hospitals | • 2 National Referral Hospitals | |

|

Lesotho (https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Lesotho-Health-Systems-Assessment-2010.pdf)) (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Lesotho/19_04_2013_lesotho_hssp.pdf) |

I. Community/primary: Health Posts provide community outreach services, promotive, preventive, and rehabilitative care in addition to organizing health education gatherings and immunization efforts. Health Centres are the first point of care within the formal health system and offer immunizations, family planning, and postnatal and antenatal care on an outpatient basis. They also supervise community public health efforts and training volunteer CHWs | • 95 Health Centres | • 188 Health Centres, |

| II. District/secondary: Filter Clinics function as “mini-hospitals,” offering curative and preventive services, limited inpatient care. laboratory and radiology services. District Hospitals handle more complex cases including minor and major operative services, ophthalmic care, counseling and care of rape victims, radiology, dental services, mental health services, and blood transfusions and preventive care, TB, HIV, and noncommunicable diseases |

• 8 Mission Hospitals • 11 District Hospitals • 2 Filter Clinics |

• 18 Hospitals • 3 Filter Clinics |

|

| III. National/tertiary: National Referral Hospitals receive referrals from filter clinics and district hospitals | • 1 National Referral Centre | • 1 Referral Hospital | |

|

Liberia |

I. Primary: Community-based services occur within the radius of a Public Health Care (PHC) facility catchment population. Non-facility-based service delivery points (SDPs) (e.g. mobile clinics or community-based providers) offer services by a skilled provider on a regular basis outside of a health facility. Clinics offer the whole Essential Package of Health Services (EPHS) for the primary level and may or may not have a laboratory | • 661 Clinics | • 496 Clinics |

| II. Secondary: Health Centres offer 24-hour primary care services complemented by a small laboratory and inpatient services. County Hospitals are the most comprehensive type of referral facility for the counties and serve as the referral facilities for the clinics and health centres |

• 41 Health Centres • 8 Mission Hospitals • 29 Hospitals |

• 43 Health Centres • 27 Hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Medical Centre (JFKMC), the national referral hospital is the top teaching hospital for physicians and medical doctors. There are also a limited number of county hospitals serving as Regional Referral Hospitals which are located within reasonable access of the county hospitals that refer to them and provide specialized consultative care such as orthopedics and ear, nose and throat services. | • 1 National Referral Hospital | • 1 National Referral Hospital | |

|

Madagascar (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/madagascar/pdss_2015.pdf) |

I. Primary: first point of contact in the system. Basic Health Centres I (CSB I) provide curative and preventive care and are run by para-medical officers. Basic Health Centres II (CSB II) provide the same healthcare only that urban dispensaries and maternity care Centres are attached to them, and they are run by a Physician |

• 910 Health Posts • 1642 Health Centres |

• 956 Basic Health Centres I • 1632 Basic Health Centres II |

| II. Secondary: District Hospital Centres I are based in district headquarters but offer similar services to those offered in a CSB II. District Hospital Centres II also based in district headquarters but function as District Hospital Centres I and additionally offer emergency surgery and comprehensive obstetrical care and referral health services | • 125 hospitals | • 87 First-Referral Hospitals | |

| III. National: Referral hospitals (CHR) and University Hospitals (CHU) serve as specialized referral Centres and the Regional Hospitals serve patients requiring a higher level of care that serve as tertiary care health facilities |

• 16 Regional Referral Hospitals • 22 University Hospitals |

||

|

Malawi (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Malawi/2_malawi_hssp_2011_-2016_final_document_1.pdf) (https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA20/SPA20%5BOct-7-2015%5D.pdf) |

I. Primary: Community Initiatives, Health Posts, Dispensaries, Maternity Facilities, Health Centres, and Community/Rural Hospitals. These cadres provide a range of mostly promotive and preventable services and some curative services |

• 22 Clinics • 87 Health Post/Dispensaries • 457 Health Centres • 2 Community Hospitals • 25 Rural Hospitals |

• 28 Health Posts • 88 Clinics • 48 Dispensaries • 477 Health Centres • 97 Hospitalsd |

| II. Secondary: District Hospitals are referral facilities for the primary level of care and provide both inpatient and outpatient services for their target populations |

• 27 Mission Hospitals • 24 District Hospitals |

||

| III. Tertiary: Central Hospitals act as referral facilities for the district hospitals while providing services in their regions. Central hospitals also have the mandate to offer professional training, conduct research, and provide support to the districts | • 4 Central Hospitals | ||

|

Mali52 |

I. Primary/health district: Community Health Centres (Centre de Santé Communautaire (CSCom)) provide basic preventive, promotional and curative health services with most having capabilities for maternal and child health |

• 94 Clinics • 1294 Community Health Centres |

• 1086 Community Health Centres |

| II. Regional/intermediate: Referral Health Centres (CSRef) and Polyclinics. CSRefs offer first level referral care for emergencies, obstetrics, surgical operations, in-patient care. |

• 61 Referral Health Centres • 11 Polyclinics |

• 60 Reference Health Centres (CSRef) | |

| III. Tertiary/central: Referral Hospitals act as second level of referral and offer all the medical and surgical specialties, high-tech laboratories and medical imaging services |

• 12 Regional Hospitals • 3 University Hospitals |

• 8 Hospitals • 3 National Hospitals |

|

|

Mauritania (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Mauritania/plannationaldveloppementsanitaire2012-2020.pdf) (https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjsmfKsjc_iAhWnxoUKHZTwABoQFjAAegQIAhAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fapps.who.int%2Fhealthinfo%2Fsystems%2Fdatacatalog%2Findex.php%2Fddibrowser%2F55%2Fdownload%2F168&usg=AOvVaw35u_wxI6WN1s9tr6inSV8J) Ministère de la Santè et des Affaires Sociales [Mauritania]. Plan stratégique national de lutte contre les èpidèmies de paludisme 2006–2010. (2005). – Document no longer available online Ministere de la Sante [Mauritania]. Carte Sanitaire Nationale de la Mauritanie. (2014) Document no longer available online |

I. Moughataa/peripheral: Basic Health Units mainly serve to extend service provided at health posts or health Centres. Health posts are run by a nurse and offer primary curative consultation, pre-natal consultation, delivery, monitoring of children under 5 years, immunization, birth spacing and distribution of essential drugs. Health Centres (Category B) provide primary curative consultation services, pre-natal consultation, delivery, monitoring of children under 5 years, immunization, birth spacing and distribution of essential drugs. Health Centres (Category A) provide inpatient services, laboratory, radiology department and a department of dental surgery in addition to services offered at health centers B. |

• 552 Health Posts • 75 Health Centres |

• 545 Basic Health Units • 530 Health posts • 67 Health Centres |

| II. Intermediate: Moughataa Hospitals, Regional Hospitals and Regional Medical Centres offer all basic services in addition to more specialist treatments/procedures | • 14 Hospitals |

• 2 Moughataa Hospitals • 6 Regional Hospitals • 6 Regional Medical Centres |

|

| III. Tertiary: national referral and includes General (National) Hospitals provide tertiary care in all medical and surgical specialties, including training and research activities. Specialized Hospitals, develop high-precision technology in a single specialty in addition to playing the same function of the national hospital | • 4 General Hospitals | • 4 General Hospitals | |

|

Mauritius (http://health.govmu.org/English/Documents/2018/ANNUAL%20REPORT%202017%20FOR%20PRINTING.pdf) |

I. Primary: Area Health Centres (AHCs), Medi-Clinics (MCs) and Community Hospitals (CH) are the first points of contact and services include X-Ray, dental care, laboratory tests and pharmaceutical services for essential drugs not requiring specialist advice. Community Health Centres (CHCs) provide health promotion, health education, family planning and primary health care diagnostic and treatment services |

• 21 Area Health Centres • 2 Health Centres • 5 Medi-Clinics • 130 Community Health Centres • 2 community hospitals |

• 26 Area Health Centres • 2 Medi-Clinics • 3 Family Health Clinics • 125 Community Health Centres • 2 community hospitals |

| II. Secondary: Regional Hospitals provide accident and emergency services, general medicine, general and specialised surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics, chest medicine, orthopaedics traumatology, paediatrics and intensive care services. Radiotherapy services are provided at Victoria Hospital |

• 3 District hospitals • 5 Regional hospitals |

• 3 District hospitals • 5 Regional hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: National specialized centres e.g. Cardiac Centre | |||

|

Mozambique (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/mozambique/mozambique_-_health_sector_strategic_plan_-_2014-2019.pdf) |

I. Primary: Health Posts are staffed by CHWs, elementary nurses and midwifes who provide information, conduct education, communication (IEC) for pregnancy, malaria, WASH, nutrition, routine immunization, nutritional assessments, malaria case management and family planning. Health Centres I and II mostly serve rural areas while Health Centres C and A mostly serve urban Centres. They all provide essential curative services including vaccination and prevention of local endemic diseases. |

• 262 Posto de Saúde • 130 Centro de Saúde Rural I • 982 Centro de Saúde Rural II • 39 Centro de Saúde Urbano A • 56 Centro de Saúde Urbano B • 49 Centro de Saúde Urbano C |

• 1395 Level I Facilities |

| II. Secondary: Rural Hospitals, District Hospitals and General Hospitals conduct routine surgical interventions with larger diagnostic capacity such as X-ray facilities and serve as first point of reference for level I and II facilities |

• 29 Hospital Rural • 16 Hospital Distrital • 5 Hospital Geral |

• 48 Level II Facilities | |

| III. Tertiary: Provincial Hospitals provide limited tertiary care including referral for lower level facilities in addition to the primary care services. | • 8 Hospital Provincial | • 7 Level III Facilities | |

| IV. Quaternary: Central Hospitals and Specialized Hospitals are in each region and provide a broader range of specialized, curative, surgical and rehabilitative services | • 3 Hospital Central | • 3 Level IV Facilities | |

|

Namibia (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Namibia/namibia_national_health_policy_framework_2010-2020.pdf) (https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA16/SPA16.pdf) (http://s3.amazonaws.com/zanran_storage/hs2020.org/ContentPages/1032599816.pdf) |

I. Outreach services: Identifies health needs and refers to the clinic. They also provide home based health care services | • 1150 Outreach Points | |

| II. Primary: Health Centres offer promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative and supervisory services to the community based health care providers. Supports clinics and engages in in-service training and operational research. Clinics offer promotive, preventative and rehabilitative services and management of outreach services |

• 287 Clinics • 43 Health Centres |

• 309 Clinics and Health Centres | |

| III. Secondary: District Hospitals are used mostly as first referral facilities for clinics and health centres |

• 3 Mission Hospitals • 29 District Hospitals |

• 29 District Hospitals | |

| IV. Tertiary: National Referral Hospitals and Intermediate Hospitals offer teaching facilities and specialized medical services such as: ambulatory, in-patient, maternity emergency obstetric care, and rehabilitative services. They link up with other national and international health care providers |

• 3 Intermediate Hospitals • 1 Central Hospital |

• 4 Intermediate and Referral Hospitals | |

|

Niger53 |

I. Health district/operational level: Health Huts are village level facilities supervised by the Integrated Health Centre and provide health care services in rural areas. Integrated Health Centres (CSI) are the first level of primary health service and are further classified based on the population they serve (CSI I & II). District Hospitals provides diagnostic services, outpatient and inpatient care, and emergency obstetrics |

• 2009 Health Huts • 836 Integrated Health Centres |

• 2160 Health Huts • 829 Integrated Health Centres • 33 District Hospitals |

| II. Intermediate/regional: Regional hospitals primarily act as referral facilities to lower-level facilities at the health district/operational level | • 40 Hospitals | • 6 Regional Hospitals | |

| III. Central: National Hospitals, General Reference Hospitals and Maternal and Child Hospital handle major illness such as TB, Leprosy in additional to all services of the lower levels with more specialist treatment and procedures | • 1 University Hospital | • 3 National University Hospitals | |

|

National Agency for Control of HIV/AIDS [Nigeria]. National Baseline Survey of Primary Health Care Services and Utilization in Nigeria: Survey Report. (2011) – Report no longer available online |

I. Primary: Primary Health Care (PHC) facilities provide first point of contact with the national health system. Comprehensive Health Centres (CHC), Model PHC, Primary Health Centres, Health Clinics, Dispensaries and Health Posts all are first point of care in the health system and provide curative and preventive services |

• 3058 Health Posts • 3239 Dispensaries • 4354 clinics • 568 Basic Health Centres • 4639 Primary Health Centres • 3402 Health Centres • 434 Comprehensive Health Centres • 58 Model Primary Health Centres • 108 Model Health Centres • 19 Medical Centres • 10 Polyclinics |

NR |

| II. Secondary: District and General Hospitals are referral centres for PHC facilities and provide out-patient and in-patient services, general medical and surgical operations, laboratory, blood bank services, rehabilitation and physiotherapy. |

• 141 Hospitals • 19 Rural Hospitals • 149 Cottage Hospitals • 16 District Hospitals • 529 General Hospitals • 12 State Hospitals |

NR | |

| III. Tertiary: Teaching Hospitals, Federal Medical Centres, National Laboratories and other Specialist Hospitals that provide care on specific diseases such as orthopedic, eye, psychiatric, maternity and pediatric cases |

• 19 Federal Medical Centres • 33 Tertiary Hospitals |

NR | |

|

Rwanda (http://www.moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/Docs/HSSP_III_FINAL_VERSION.pdf) |

I. Community health: Outreach Services conducted by CHWs and are supervised administratively by those in charge of social services and technically by those in charge of health Centres | ||

| II. Peripheral: Dispensaries offer primary health care, outpatient, and referral. Health Posts undertake outreach activities (i.e., immunization, family planning, growth monitoring, antenatal care) |

• 37 Health Posts • 2 Secondary Health Posts |

• 44 Health Posts | |

| III. Intermediate: District Hospitals offer inpatient/outpatient services, surgery, laboratory, gynecology, obstetrics, and radiology. Health Centres offer prevention activities, primary health care, inpatient, referral, and maternity |

• 486 Health Centres • 36 District Hospitals |

• 450 Health Centres • 40 District Hospitals |

|

| IV. Tertiary: National Referral Hospitals offer inpatient/outpatient services, surgery, laboratory, gynecology, obstetrics, and radiology; specialized services including ophthalmology, dermatology, ear nose and throat, stomatology, and physiotherapy. They also offer training to doctors and pharmacists |

• 4 Provincial Hospitals • 3 Referral Hospitals • 4 National Referral Hospitals |

• 5 Provincial Hospitals • 4 Referral Hospitals |

|

|

São Tomé and Príncipe (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Sao%20Tome%20and%20Principe/ppac_version_du_31-05-11.pdf) (https://interlusofona.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/saude_para_todos_-_estudo_de_caso.pdf) (https://repositorio.hff.min-saude.pt/bitstream/10400.10/440/1/Apresentacao%201.pdf) |

I. District/operational: Community Health Posts are informal units managed by CHWs and provide basic care, first aid as well as counseling, vaccination and nutrition and reproductive education to the rural community. Health Posts are the basic health units that offer basic nursing care and are managed by a general nurse who visits regularly. Health Centres receive referrals from health posts and community health posts and provide outpatient care except for a few which offer some inpatient care |

• 13 Community Health Posts • 29 Health Posts • 6 Health Centres |

NR |

| II. Central: Central Hospitals provide both general and specialized treatments to both inpatients and outpatients | • 2 Hospitals | NR | |

|

Senegal (https://www.itdp.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ITDP-Transport-and-Health-Care-Senegal.pdf) |

I. Peripheral/health post: Health Points/Huts form the lowest level and are the foundation of the health delivery system. Services offered are promotional, integrated package of maternal and child health, malaria, nutrition and, in many cases, family planning services, basic curative including dressing wounds. Health Posts are responsible for health points that are within their jurisdiction and provide preventive and primary curative services, prenatal care, family planning, and health promotion | • 1231 Health Posts | • 971 Health Posts |

| II. Intermediate/health centre: Health Centres are staffed by 1-2 doctors, and 15 -20 health workers and are responsible for health posts within their area and handle all cases referred by health posts. District health Centres provide first-level referrals and limited hospitalization services with between 10-20 beds | • 87 Health Centres | • 70 Health Centres | |

| III. Central/hospital: National Hospitals and Regional Hospitals provide highly specialized referral services and training |

• 8 Hospitals • 1 General Hospital • 13 Regional Hospitals • 5 National Hospitals • 2 University Hospitals |

• 20 Hospitals | |

|

Seychelles (http://www.health.gov.sc/wp-content/uploads/SEYCHELLES-NATIONAL-HEALTH-STRATEGIC-PLAN.pdf) |

I. Tier 1. District Health Centres provide clinical and rehabilitative services | • 17 District Health Centres | • 17 District Health Centres |

| II. Tier 2: Cottage Hospitals provide specialized services | • 3 Cottage Hospitals | • 3 Cottage Hospitals | |

| III. Tier 3: Mahe (Victoria) National Referral Hospital is the main referral for all district health centres | • 1 National Referral Hospital | • 1 National Referral Hospital | |

|

Sierra Leone57 (https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/ebola/files/SL_Health_Facility_Survey_2014Dec3.pdf) (http://www.ministerial-leadership.org/sites/default/files/resources_and_tools/NHSSP%202010-2015.pdf) |

I. Primary: Maternal and Child Health Posts (MCHP) are the first level of contact for patients in rural settings. They offer antenatal, delivery and postnatal care. Community Health Posts are situated in small towns and have similar functions to the MCHP with added curative functions. Community Health Centres have preventive, promotive and curative functions and offer inpatient care and laboratory services. They can also handle some complications; grave cases of childhood illness; treatment of complicated cases of malaria and inpatient and outpatient physiotherapy for disability |

• 11 Clinics • 619 Maternal and Child Health Posts • 217 Community Health Posts • 25 Health Posts • 206 Community Health Centres • 10 Health Centres |

• 66 Clinics • 520 Maternal and Child Health Posts • 176 Community Health Posts • 178 Community Health Centres |

| II. District: District Hospitals are secondary level facility providing referral support to PHUs. They provide out-patient, inpatient and diagnostic services, management of accidents and emergencies, and technical support to primary facilities |

• 12 Mission Hospitals • 19 Hospitals |

• 11 Mission Hospitals • 30 Government Hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: Regional National Hospitals provide tertiary care and a wider range of essential drugs and laboratory services than the lower levels. They are staffed by doctors, including male or female OB/GYNs, surgeon, anaesthetist, and paediatrician; midwives; lab and X ray technicians; pharmacist; and dentist and dental technician | • 1 Referral Hospital | ||

|

Somalia Zonal Malaria Control Programmes/Ministry of Health [Somalia, Puntland & Somaliland). National Malaria Strategic Plan 2016-2020. (2016). (www.somalilandmoh.org/wp-content/…/Somali-Malaria-Strategic-Plan-2016-2020.pdf) – link is no longer accessible. |

I. Primary Health Units (PHUs): formed from health posts and staffed by at least one trained Community Health Worker (CHW) and provide basic health prevention and promotion services | • 442 Health Posts | • 269 Primary Health Units |

| II. Health Centres (HCs) are the key service delivery units providing maternal and child health services, a delivery unit and a six-bed observation unit. Maternal and Child Health centres and Outpatient Departments not meeting these criteria will become PHUs |

• 334 Maternal & Child Health Centres • 24 Health Centres |

• 198 Maternal and Child Health Centres | |

| III. Referral Health Centres (RHCs) and District Hospitals provide the next level of services that include comprehensive obstetric care |

• 70 Hospitals • 3 District Hospitals |

• 26 District Hospitals • 10 Regional Hospitals |

|

| IV. Referral Hospitals provide 24-hour uninterrupted services and are staffed by resident doctors and specialists |

• 5 Regional Hospitals • 1 Referral Hospital |

• 8 Referral Hospitals | |

|

South Africa (https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201707/40955gon627.pdf) |

I. Primary: District services: Primary Health Care (PHC) Services: Community Clinics and Community Health Centres (CHC’s) and District Hospitals |

• 3435 Clinics • 205 Satellite Clinics • 34 Health Posts • 8 Community Health Centres/Clinics • 284 Community Health Centres • 9 Community Health Centres (After hours) • 1 Medical Centre • 254 District Hospitals |

• 3760 Primary Health Care Facilities (clinics, community health centres & district hospitals) |

| II. Secondary: Regional Hospitals | • 47 Regional Hospitals | NR | |

| III. Tertiary: Provincial Hospitals | • 17 Provincial Tertiary Hospitals | NR | |

| IV. Quaternary: National and Central Referral Centres | • 9 National Central Hospitals | • 10 Central Hospitals | |

|

South Sudan (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/South%20Sudan/south_sudan_hsdp_-final_draft_january_2012.pdf) |

I. Primary: Primary Health Care Units (PHCUs) provide basic, preventive, promotive and curative services | • 1375 Primary Health Care Units | • 792 Primary Health Care Units |

| II. Intermediate: Primary Health Care Centres (PHCCs) deliver diagnostic laboratory services, maternity and inpatient care in addition to services provided by the PHCUs | • 332 Primary Health Care Centres | • 284 Primary Health Care Centres | |

| III. Referral: County Hospitals (CHs) and State Hospitals (SH) provide emergency surgical operations in addition to services provided by PHCCs in addition to training and mentoring of interns |

• 28 County Hospitals • 9 State Hospitals |

• 27 County Hospitals • 7 State Hospitals |

|

| IV. Tertiary: Teaching Hospitals (THs) should provide tertiary care in addition to training of medical professionals and conducting research. Mostly they provide basic services due to lack of equipment and qualified personnel | • 3 Teaching Hospitals | • 3 Teaching Hospitals | |

|

Sudan58 (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Sudan/sudan_25-year_strategic_plan_for_health.pdf) |

I. Primary: Basic Health Units (BHUs) are the minimum facility level for and are structured and staffed to deliver the essential package of primary healthcare services. Health Centres are the first referral point for BHUs and are supposed to be headed by a physician | NR | NR |

| II. Secondary: Rural Hospitals are referral facilities for primary healthcare facilities and have inpatient capability |

• 125 Hospitals • 3 Type A Hospitals • 7 Type B Hospitals • 7 Type C Hospitals • 123 Type D Hospitals |

• 250 Rural Hospitals • 166 other public hospitals |

|

| III. Tertiary: Teaching Hospitals and Specialized Hospitals offer advanced specialized services and are training hospitals for both undergraduate and postgraduate students |

• 1 Referral Hospital • 1 National Hospital • 5 Teaching Hospitals |

||

|

eSwatini59 (http://www.gov.sz/index.php/ministries-departments/ministry-of-health/clinical-services) (http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/swaziland/swaziland_strategic_plan_2008-2013pdf.pdf) (http://www.gov.sz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=565&Itemid=577) |

I. Primary: consists of CHWs, clinics and outreach Services including health promotion in rural areas that focus on prevention of malaria and HIV/AIDS. Clinics are the first point of care and offer primary care, vaccination and family planning. Outreach Clinics provide community-based care and are owned mostly by FBOs and CBOs with little government support |

• 23 Clinics • 78 Clinics without Maternity • 12 Clinics with Maternity |

|

| II. Secondary: Health Centres and Public Health Units offer both inpatient and outpatient services and act as referral points for clinics. Services provided include dental, VCT, Prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT), obstetric, pediatric, and minor surgery |

• 8 Public Health Units • 8 Health Centres |

• 149 Clinics and Health Centres (approx.) | |

| III. Tertiary: Regional Hospitals, Specialized Hospitals and The National Referral Hospital handle complicated surgical procedures and specialized services such as psychiatric treatment, TB, dental, emergency and ambulatory services, occupational health, pediatric, and Mortuary services. Complicated cases are referred to South Africa |