Abstract

Background

The purpose of this multistage, adaptively, designed randomized phase II study was to evaluate the role of intraperitoneal (i.p.) chemotherapy following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and optimal debulking surgery in women with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC).

Patients and methods

We carried out a multicenter, two-stage, phase II trial. Eligible patients with stage IIB–IVA EOC treated with platinum-based intravenous (i.v.) NACT followed by optimal (<1 cm) debulking surgery were randomized to one of the three treatment arms: (i) i.v. carboplatin/paclitaxel, (ii) i.p. cisplatin plus i.v./i.p. paclitaxel, or (iii) i.p. carboplatin plus i.v./i.p. paclitaxel. The primary end point was 9-month progressive disease rate (PD9). Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), toxicity, and quality of life (QOL).

Results

Between 2009 and 2015, 275 patients were randomized; i.p. cisplatin containing arm did not progress beyond the first stage of the study after failing to meet the pre-set superiority rule. The final analysis compared i.v. carboplatin/paclitaxel (n = 101) with i.p. carboplatin, i.v./i.p. paclitaxel (n = 102). The intention to treat PD9 was lower in the i.p. carboplatin arm compared with the i.v. carboplatin arm: 24.5% (95% CI 16.2% to 32.9%) versus 38.6% (95% CI 29.1% to 48.1%) P = 0.065. The study was underpowered to detect differences in PFS: HR PFS 0.82 (95% CI 0.57–1.17); P = 0.27 and OS HR 0.80 (95% CI 0.47–1.35) P = 0.40. The i.p. carboplatin-based regimen was well tolerated with no reduction in QOL or increase in toxicity compared with i.v. administration alone.

Conclusion

In women with stage IIIC or IVA EOC treated with NACT and optimal debulking surgery, i.p. carboplatin-based chemotherapy is well tolerated and associated with an improved PD9 compared with i.v. carboplatin-based chemotherapy.

Clinical trial number

clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01622543.

Keywords: i.p. chemotherapy, ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant

Key Message

The OV.21/PETROC trial demonstrated that in women with epithelial ovarian cancer post neoadjuvant therapy followed by optimal debulking surgery, the Progressive Disease rate at 9 months was significantly better using a carboplatin based intravenous/intraperitoneal (IV/IP) regimen compared to carboplatin based IV chemotherapy: 23.2% versus 42.2%, P=0.03. IP chemotherapy is tolerable and feasible.

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the leading cause of death from gynecologic malignancy in the developed world with the majority of women presenting with stage III/IV disease [1]. The peritoneal cavity is the principal site of disease and intraperitoneal (i.p.) chemotherapy has been investigated as a means of increasing the dose intensity delivered to the tumor [2]. At the time OV21/PETROC was conceived, three randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and a meta-analysis had demonstrated improved survival for women with stage III EOC who received a combination of intravenous (i.v.) and i.p. chemotherapy following optimal, primary debulking surgery [3–5]. An update of the most recent of these trials, GOG 172, confirmed a continued benefit for women who had received the experimental arm [6]; i.p./i.v. chemotherapy, however, remains controversial [7]. Debate has centered on the impact of drug scheduling on the i.p. benefits and concerns over the toxicity of i.p. cisplatin, used in the positive studies, compared with i.v. carboplatin [8].

The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) before a definitive debulking attempt is increasingly used in advanced EOC [9, 10] based on two RCTs which demonstrated non-inferiority and lower perioperative morbidity compared with primary surgery followed by chemotherapy [11, 12]. None of the i.p./i.v. RCTs included patients who had undergone optimal debulking surgery following NACT.

OV21/PETROC investigated the hypothesis that women undergoing NACT followed by optimal debulking surgery would benefit from i.v./i.p. chemotherapy.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients were eligible if they had histologically confirmed EOC, primary peritoneal or fallopian tube carcinoma, were FIGO [13] stage IIB–IVA (pleural effusion only) at initial diagnosis, had undergone three or four cycles of platinum-based NACT followed (within 6 weeks) by optimal (≤1 cm) debulking surgery and had an ECOG performance status of 0–2. Exclusion criteria included: mucinous or borderline histology, extensive intra-abdominal adhesions, bowel obstruction or unresolved > grade 2 peripheral neuropathy.

Trial design

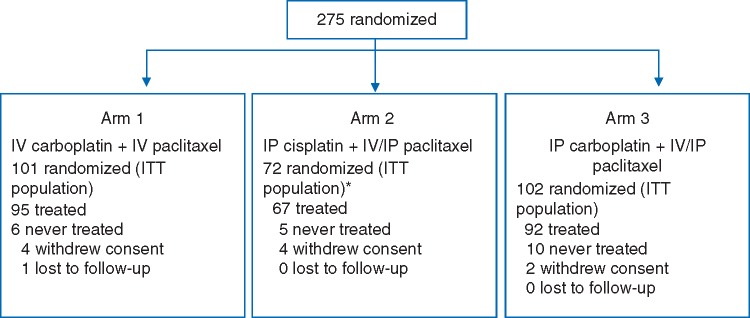

OV21/PETROC was a Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) study developed by the Canadian Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) in collaboration with the National Cancer Research Institute (UK) and was approved by institutional ethics boards of participating institutions. OV21/PETROC was a randomized multistage study. The initial stage of the study was designed to ‘pick the winner’ of two i.p. chemotherapy regimens to carry forward into a two-arm (i.v. versus i.p.) phase III comparison with progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary outcome. However, due to poor accrual and following Independent Data Monitoring Committee review, the design was subsequently amended to an expanded two-arm phase II study using the primary outcome measure of PD9, defined as the proportion of patients with disease progression or death due to any cause occurring within 9 months of randomization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

OV21/PETROC flow diagram.

Protocol therapy

Randomization was permitted intraoperatively or within 6 weeks of debulking surgery using a central, web-based minimization procedure with the following stratification factors: Cooperative Group, reason for NACT (unresectable disease versus other), residual disease (macroscopic versus microscopic), and timing of i.p. catheter placement (intraoperatively or postoperatively by interventional radiology) (see IR—Appendix protocol for details).

Protocol chemotherapy was administered every 21 days for three cycles. Stage I patients were randomized 1 : 1 : 1 to arm 1: paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 i.v. and carboplatin area under the curve (AUC) 5/6 i.v. on day 1 with paclitaxel 60 mg/m2 i.v. on day 8; arm 2: paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 i.v. and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 i.p. on day 1, with paclitaxel 60 mg/m2 i.p. on day 8; or arm 3: paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 i.v. and carboplatin AUC 5/6 i.p. day 1, with paclitaxel 60 mg/m2 i.p. on day 8. After stage I, patients were randomized 1 : 1 to the i.v. arm (arm 1) and the remaining i.p. arm. Carboplatin dosing was AUC 5 if a measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was available and AUC 6 if an estimated GFR was used. Doses were adjusted for grade 3 adverse events (AEs) (≥grade 2 for neurotoxicity); while grade 4 AEs or ≥grade 3 neurotoxicity led to drug discontinuation. Patients not tolerating i.p. chemotherapy were offered institutional standard i.v. chemotherapy.

Assessments and outcome measures

The primary end point for the study was PD9 rate. Disease progression was defined using RECIST V1.1 and/or GCIG CA125 criteria [14, 15]. Secondary end points included PFS, OS, feasibility, safety, and quality of life (QOL) assessed using questionnaires EORTC QLQ-C30 [16], EORTC QLQ-OV28 [17, 18] and FACT/GOG-Ntx [19]. AEs were coded using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0.

Physical examination, biochemistry and CA125 were assessed on day 1 of each cycle and complete blood count on days1, 8 and 15. Imaging studies were done at the end of treatment; every 6 months for 2 years and then as clinically indicated. Patients were reviewed (physical examination, CA125) post treatment at 6 weeks, every 3 months for 2 years, every 6 months years 2–4 then annually until death. QOL instruments were collected at 3, 6, and 12 months then annually.

Statistical methods

First stage

After the first 50 patients randomized to each arm had a minimum 9-month follow-up, an independent Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) reviewed PD9, compliance, and safety to determine whether the trial should continue to the second stage. An i.p. arm would be considered as futile to continue if its PD9 was 5% or greater than that of the i.v. arm, which had an expected PD9 of 40% (based on results of a previous front-line randomized study [20] adjusted for the randomization timing in OV21/PETROC after NACT). If neither i.p. arm met criteria for futility, the arm with lower PD9 would be selected for the second stage unless ≥29 patients failed to complete that i.p. treatment due to toxicity.

Second stage

A sample size of 200 in the second stage, including patients accrued in stage I, permitted detection of a 19% difference in PD9 between arms 1 (assumed to be 40%) and the selected i.p. arm (arm 3) with 80% power at two-sided 0.05 level. This absolute difference was considered relevant based on PD9 data extrapolated from GOG172 [4]. The final analysis of both intention to treat (ITT- as randomized) and per protocol (eligible, received at least one dose of protocol treatment, not lost to follow-up or consent withdrawal) populations was carried out once all patients had 9-month follow-up. A stratified Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test adjusting for stratification factors at randomization was the primary method used to compare PD9 between the two treatment arms. Odds ratio and associated 95% confidence interval were obtained from stratified logistical regression models. PFS and OS were summarized using Kaplan–Meier plots and compared using the stratified log-rank test. Estimates of the relative treatment differences were obtained from hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs from stratified Cox regression models.

Analyses of QOL data using previously described methodology [21, 22], were restricted to patients who had a baseline and at least one assessment on study. Chi-square test was used to compare the distributions of response categories between arms.

Safety was evaluated in patients who received at least one dose of protocol therapy.

Results

Patients and protocol treatment received

Between September 2009 and May 2015, 275 patients were randomized: 101 in arm 1 (i.v. alone), 72 in arm 2 (i.p. cisplatin-based regimen) and 102 in arm 3 (i.p. carboplatin-based regimen). A total of 254 patients received at least one dose of protocol therapy (Figure 1); 72 patients were accrued to arm 2 since accrual was not halted while awaiting stage I outcomes.

Baseline characteristics by treatment arm are presented in Table 1. The three groups were well balanced and the median time from diagnosis to randomization was 3 months. The majority of participants (72.8%) underwent intraoperative randomization.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and treatments

| Arm 1 (N = 101) | Arm 2 (N = 72) | Arm 3 (N = 102) | Total (N = 275) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. carboplatin + i.v. paclitaxel | i.p. cisplatin + i.v. /i.p. paclitaxel | i.p. carboplatin + i.v. /i.p. paclitaxel | ||

| Age | ||||

| Median (range), years | 62 (33–83) | 61 (29–78) | 62 (40–82) | 62 (29–83) |

| ≤65 | 65 (64.4) | 52 (72.2) | 71 (69.6) | 188 (68.4) |

| >65 | 36 (35.6) | 20 (27.8) | 31 (30.4) | 87 (31.6) |

| Race or ethnic group | ||||

| White | 92 (91.1) | 67 (93.1) | 95 (93.1) | 254 (92.4) |

| Black or African American | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (1.1) |

| Asian | 5 (5.0) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (3.9) | 10 (3.6) |

| Other | 3 (3.0) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.0) | 8 (2.9) |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 46 (45.5) | 41 (56.9) | 49 (48.0) | 136 (49.5) |

| 1 | 53 (52.5) | 29 (40.3) | 47 (46.1) | 129 (46.9) |

| 2 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (5.9) | 10 (3.6) |

| Primary site | ||||

| Ovary | 75 (74.3) | 55 (76.4) | 73 (71.6) | 203 (73.8) |

| Peritoneal | 17 (16.8) | 16 (22.2) | 20 (19.6) | 53 (19.3) |

| Fallopian tube | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.4) | 7 (6.9) | 14 (5.1) |

| Other or unknown | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (1.0) |

| Histologic type | ||||

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 95 (94.1) | 69 (95.8) | 95 (93.1) | 259 (94.2) |

| Adenocarcinoma, unspecified | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.8) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (2.9) |

| Other or unknown | 3 (3.0) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (3.9) | 8 (2.9) |

| Histologic grade | ||||

| Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated (III) | 91 (90.1) | 65 (90.3) | 96 (94.1) | 252 (91.6) |

| Intermediate differentiation (II) | 3 (3.0) | 5 (6.9) | 3 (2.9) | 11 (4.0) |

| Unknown | 7 (6.9) | 2 (2.8) | 3 (2.9) | 12 (4.4) |

| Months from histologic diagnosis to randomization | ||||

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0–4.7) | 2.8 (0–5.9) | 3.2 (0–5.3) | 3.0 (0–5.9) |

| Stage at initial diagnosis | ||||

| IIB | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| IIC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| IIIB | 6 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.9) | 12 (4.4) |

| IIIC | 82 (81.2) | 61 (84.7) | 82 (80.4) | 225 (81.8) |

| Iva | 12 (11.9) | 10 (13.9) | 13 (12.7) | 35 (12.7) |

| Reason for NACT before debulking surgery | ||||

| Unresectable disease | 85 (84.2) | 61 (84.7) | 84 (82.4) | 230 (83.6) |

| Other | 16 (15.8) | 11 (15.3) | 18 (17.6) | 45 (16.4) |

| Delayed interval debulking surgery | ||||

| Weeks from NACT last cycle to surgery | ||||

| Median (range) | 4.1 (2.4–6.9) | 4.1 (1.6–6.3) | 4.0 (1.7–6.1) | 4.1 (1.6–6.9) |

| Presence of disease at end of surgery | 40 (39.6) | 30 (41.7) | 37 (36.3) | 107 (38.9) |

| Days from surgery to randomization | ||||

| 0 (perioperative) | 78 (77.2) | 58 (80.6) | 78 (76.5) | 214 (72.8) |

| 1–7 | 4 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (1.8) |

| 8–14 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.0) | 4 (1.5) |

| ≥15 | 18 (17.8) | 13 (18.1) | 21 (10.6) | 52 (18.9) |

| Days from surgery to day 1 of cycle 1 | ||||

| Median (range) | 28 (5–50) | 32 (7–56) | 32 (7–51) | 31 (5–56) |

Data are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified.

i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous; NA, not applicable; NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Most patients (88% arm 1, 72% arm 2, and 76% arm 3) were able to complete three cycles of chemotherapy. Seven i.p. patients crossed over to i.v. chemotherapy (three in arm 2 and four in arm 3).

Efficacy

First stage

Stage I analysis included 51 patients on each arm. The PD9 at this time was 37.3% on arm 1, 45.1% on arm 2, and 27.5% on arm 3. As per the statistical plan, arm 2 accrual was discontinued. Follow-up was maintained on all patients until the final analysis.

Second stage

A total of 203 patients were enrolled in arms 1 and 3. As shown in Table 2, for the ITT population, the PD9 was 38.6% (95% CI 29.1–48.1) in arm 1 (i.v.), and 24.5% (95% CI 16.2–32.9) in arm 3 (i.p. carboplatin), P = 0.065. For the per protocol population analysis, the PD9 was 42.2% (95% CI 31.9–53.1) arm 1 and 23.3% (95% CI 15.1–33.4) arm 3, P = 0.03.

Table 2.

Progression events (ITT analysis)

| Arm 1 (N = 101) |

Arm 2 (N = 72) |

Arm 3 (N = 102) |

Crude differences in cumulative incidence of PD9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. carboplatin + i.v. paclitaxel |

i.p. cisplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel |

i.p. carboplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel |

|||||

| N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Progression or death at or before Month 9 | 39 | 38.6 | 25 | 34.7 | 25 | 24.5 | |

| (29.1 to 48.1) | (23.7 to 45.7) | (16.2 to 32.9) | |||||

| Arm 1 versus arm 3 | 14.1 (1.5 to 26.7) | ||||||

| Arm 2 versus arm 3 | 10.2 (−3.6 to 24.0) | ||||||

| Time of event | |||||||

| First relapse/progression on treatment | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Objective progression only | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| CA125 progression only | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Both objective and CA125 progressions | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| First relapse/Progression during follow-up | 39 | 24 | 24 | ||||

| Objective progression only | 17 | 5 | 7 | ||||

| CA125 progression only | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Both objective and CA125 progressions | 22 | 19 | 17 | ||||

| Death (without relapse/progression) | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous.

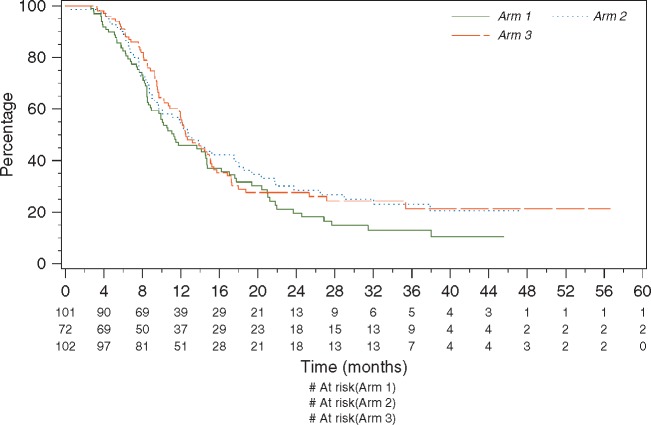

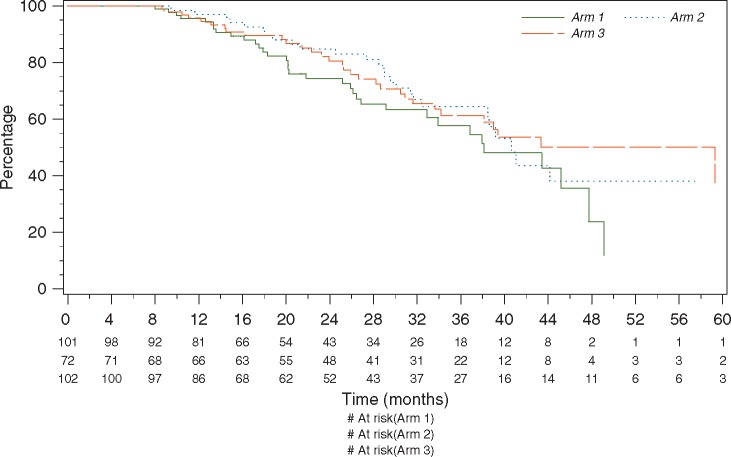

At the time of data cut-off (28 February 2016) the median follow-up was 33 months. The median PFS was 11.3 months in arm 1 and 12.5 months in arm 3 (Figure 2) with an HR of 0.82 95% CI (0.57–1.17). The 2-year OS was 74.4% in arm 1, and 80.6% in arm 3 (Figure 3), HR 0.80, 95% CI (0.47–1.35) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

PFS arm 1: i.v. carboplatin + i.v. paclitaxel; arm 2: i.p. cisplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel; arm 3: i.p. carboplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel.

Figure 3.

Overall survival—arm 1: i.v. carboplatin + i.v. paclitaxel; arm 2: i.p. cisplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel; arm 3: i.p. carboplatin + i.v./i.p. paclitaxel.

Adverse events

Severe treatment-related (≥ grade 3) AEs during protocol therapy occurred in 23% of patients in arm 1, 22% in arm 2, and 16% arm 3 (P = NS, details in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The most common severe AEs (≥5% in at least one treatment arms) were febrile neutropenia (arm 1: 5.3%, arm 2: 1.5%, arm 3: 1.1%) and abdominal pain (arm 1: 1.1%, arm 2: 6.0%, arm 3: 1.1%). Catheter-related complications, obstruction being the most common, led to treatment discontinuation in 8 (11.9%) patients in arm 2 and 7 (7.6%) in arm 3.

Quality of life

Compliance with QOL assessment was 87% at baseline and 80% at 6 months across arms. No statistically significant difference between arms was found on any scale. In particular, no differences were seen in peripheral neuropathy or gastrointestinal symptoms scales at baseline or in follow-up between all arms. Significant improvements in gastrointestinal functioning over time were seen in all arms (see detailed QOL response by treatment arm in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

OV21/PETROC was designed to answer two clinically important questions: the role of i.p./i.v. chemotherapy in the NACT patient population and to provide RCT data on an i.p. carboplatin-based regimen. The study demonstrates that i.p./i.v. chemotherapy is safe and well tolerated in this patient population with no detriment to QOL. Although delivery of i.p./i.v. chemotherapy was associated with a 17.7% improvement in the PD9 (ITT) (18.9% improvement, per protocol treatment), similar to that extrapolated from GOG 172 [4], the trial is underpowered to draw firm conclusions about PFS and OS. OV21/PETROC provides data for discussion with patients around the use of i.p. carboplatin-based regimens which have, in some cases, been adopted in the community without RCT data [7].

OV21/PETROC had a novel, adaptive, two-stage design. The PD9, post-randomization, end point was selected as a surrogate measure of efficacy to allow for a seamless transition into the second stage of the trial. To avoid the criticism levelled at previous studies the regimens included in the trial were balanced for both schedule and dose of paclitaxel and carboplatin [8]. As a result, the i.v. reference arm (with day 8 paclitaxel) was not a previously reported, standard of care. However, the observed PD9 of 42.2% is reassuringly consistent with the (40%) rate observed for the i.v. arm in our previous study [20]. At the end of the first stage of this trial, arm 2 (i.p. cisplatin) was discontinued due to lack of efficacy compared with the i.v. regimen. The prior positive, frontline i.p. RCTs investigated regimens containing i.p. cisplatin 100 mg/m2 [3–5]. Our use of a lower dose (cisplatin 75 mg/m2) was based on concerns over toxicity at 100 mg/m2 and this may have impacted efficacy. These data plus the initial findings of GOG 252, that also show no benefit for i.p. cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 [23], do not support using 75 mg/m2 cisplatin i.p. in practice.

A major limitation of OV21/PETROC was the revision of the statistical design for the second stage of the trial. The independent DSMC were asked to make a recommendation, based on the study’s potential to provide clinically useful information, to either stop the trial or to continue with a limited expansion into the two-arm stage. Whilst acknowledging that PD9 represented an unconventional end point, the DSMC recommended amending the protocol. In addition, the comparison of i.p. and i.v. carboplatin-based regimens provides additional data on QOL and toxicity. Further data on the upfront use of i.p. carboplatin (alone) are awaited from the JGOG iPocc study and survival analysis of GOG 252 which also investigated an i.p. carboplatin arm [23].

Placing the OV21/PETROC data in the context of other NACT studies is challenging given that study entry/randomization was at the time of debulking surgery. However, in over 80% of cases the decision to select NACT was inoperable disease with over 90% having stage IIIC–IV disease. This aligns with entry requirements for other NACT studies [11, 12]. Median OS (from randomization) observed in OV21/PETROC (microscopic and <1 cm) was 38.1 months in the i.v. arm and 59.3 months for the i.p./i.v. arm. Making a conservative presumption of 10 weeks from date of first preoperative chemotherapy to randomization (three cycles of chemotherapy and median 4-week time interval to surgery in OV21/PETROC) would translate into an OS from diagnosis of 40.6 months in the i.v. arm and 61.8 months in the i.p./i.v. arm. Although the comparison is crude, the i.v. arm of OV21/PETROC does appear to be performing in a similar range to the other NACT studies. These earlier studies would, however, have included patients with a poorer prognosis as all patients in OV.21-PETROC underwent surgery whereas in the other trials, patients were entered at diagnosis and some progressed before NACT. The i.p. arm is certainly no worse than the i.v. arm and, had the study been completed as originally intended, raises the intriguing possibility that it may have been better.

Interpretation of the clinical relevance of OV21/PETROC is limited by the lack of power to detect changes in PFS and OS; i.p. chemotherapy remains controversial. OV21/PETROC does, however, provide RCT data both to support the use of i.p. carboplatin and to inform clinicians and patients when making choices about subsequent therapy following NACT and optimal debulking surgery. Correlative studies are planned to identify potential predictive biomarkers and inform the design of future clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

OV.21 study investigators

Canada: Dr H. Bliss Murphy Cancer Centre: Patti Power; QEII Health Sciences Centre: Katharina Keiser; Atlantic Health Sciences Corporation: Margot Burnell; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire De Sherbrooke: Paul Bessette; CHUQ-Pavillon Hotel-Dieu de Quebec: Marie Plante; Hopital Maisonneuve-Rosemount: Suzanne Fortin; McGill University (Jewish General Hospital): Susie Lau; CHUM-Hopital Notre-Dame: Diane Provencher; Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario at Kingston: Julie Francis; Ottawa Health Research Institute: Johanne Weberpals; Princess Margaret Hospital: Amit Oza; London Regional Cancer Program: Jacob McGee; Tom Baker Cancer Centre: Prafull Ghatage; Cross Cancer Institute: Valerie Capstick; Vancouver Cancer Centre: Anna Tinker; Fraser Valley Cancer Centre: Ursula Lee; Cancer Centre for the Southern Interior: Marianne Taylor.

NCRI (UCL), UK: Mount Vernon: Marcia Hall; Royal Marsden Hospital: Martin Gore; Derriford Hospital: Dennis Yiannakis; Western General Hospital: Charlie Gourley; Liverpool Women’s Hospital: Rosemary Lord; The Christie Hospital: Andrew Clamp; University College Hospital: Jonathan Ledermann; St. James’s University Hospital: Geoff Hall; St. Bartholomew’s Hospital: Chris Gallagher, Michelle Lockley; Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology: Rosemary Lord; St. Marys Hospital: Richard Clayton; Wexham Park Hospital: Marcia Hall.

GEICO, Spain: H. Valle Hebron: Ana Oaknin, Antonio Gill; IVO: Ignacio Romero, Christina Zorrero; H. Clinico Universitario de Valencia: Andres Cervantes, Victor Martin; H. Alcorcon: Susana Hernando, Judith Albareda; H. Clinic De Barcelona: Cecila Orbegozo, Sergio Martinez; Ico L’Hospitalet: Beatriz Pardo, Jordi Ponce; H. Sant Pau; Alfonso Gomez de Liano, Ramon Rovira.

SWOG, USA: Coxhealth—Cancer Research for the Ozarks NCORP (MO042): Robert L. Carolla; University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center– Stephenson Cancer Centre (OK003): Robert S. Mannel; Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (RI012): Cara A. Mathews; University of Utah –Huntsman Cancer Institute (UT003): Theresa L. Werner.

Funding

Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI) (#015469 and 021039); Cancer Research UK (CRUK) (CC14202/A10994); National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) study funded by Cancer Research UK Grant A18781; and SWOG NIH/NCI (CA180888, CA180798, CA189822, and CA180818).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

NCIC CTG OV.21 Protocol: A Phase II Study of Intraperitoneal (IP) Plus Intravenous (IV) Chemotherapy Versus IV Carboplatin Plus Paclitaxel in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Optimally Debulked at Surgery Following Neoadjuvant Intravenous Chemotherapy.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute: SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovary Cancer; http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html.

- 2. Dedrick RL, Myers CE, Bungay PM. et al. Pharmacokinetic rationale for peritoneal drug administration in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rep 1978; 62(1): 1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV. et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 1996; 335(26): 1950–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L. et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(1): 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS. et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. JCO 2001; 19: 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tewari D, Java JJ, Salani R. et al. Long-term survival advantage and prognostic factors associated with intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatment in advanced ovarian cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(13): 1460–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wright AA, Cronin A, Milne DE. et al. Use and effectiveness of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(26): 2841–2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gourley C, Walker JL, Mackay HJ.. Update on intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2016; 35: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyer LA, Cronin AM, Sun CC. et al. Use and effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(32): 3854–3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wright AA, Bohlke K, Armstrong DK. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer: Society of Gynecologic Oncology and American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Gynecol Oncol 2016; 143: 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M. et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015; 386(9990): 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P. et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006; 95(Suppl 1): S161–S192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rustin GJ. Follow-up with CA125 after primary therapy of advanced ovarian cancer has major implications for treatment outcome and trial performances and should not be routinely performed. Ann Oncol 2011; 22(Suppl 8): viii45–viii48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85(5): 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greimel E, Bottomley A, Cull A. et al. An international field study of the reliability and validity of a disease-specific questionnaire module (the QLQ-OV28) in assessing the quality of life of patients with ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39(10): 1402–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Preston NJ, Wilson N, Wood NJ. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in gynaecological oncology: a systematic review. BJOG 2015; 122(5): 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calhoun EA, Welshman EE, Chang CH. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity (Fact/GOG-Ntx) questionnaire for patients receiving systemic chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003; 13(6): 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoskins P, Vergote I, Cervantes A. et al. Advanced ovarian cancer: phase III randomized study of sequential cisplatin-topotecan and carboplatin-paclitaxel vs carboplatin-paclitaxel. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102(20): 1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Osoba D, Bezjak A, Brundage M. et al. Evaluating health-related quality of life in cancer clinical trials: the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group experience. Value Health 2007; 10: S138–S145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Osoba D, Bezjak A, Brundage M. et al. Analysis and interpretation of health-related quality-of-life data from clinical trials: basic approach of The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41(2): 280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walker JL, Brady MF, DiSilvestro PA. et al. A phase III clinical trial of bevacizumab with IV versus IP chemotherapy in ovarian, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal carcinoma NCI-supplied agent(s): bevacizumab (NSC #704865, IND #7921) NCT01167712 a GOG/NRG trial (GOG 252) – Late-breaking abstract. Presented at the SGO Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, 19–22 March 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.