Highlights

-

•

Isosteviol partitions extensively into plasma compartments of the blood in man and rat, with an estimated 97% bound to plasma proteins in vitro.

Key words: Cardioprotective agent, Erythrocytes, Isosteviol, Neuroprotection, Partitioning ratio, Steviol glycosides

Abstract

Background

Isosteviol is a synthetic derivative of steviol glycosides with promising pharmacological properties and might find future use as a cardioprotective agent.

Objective

A simple LC-MS/MS technique was developed and validated for the bioanalysis of isosteviol in plasma and erythrocytes. This method was subsequently utilized for the in vitro assessment of isosteviol's partitioning into blood compartments of humans and rats.

Methods

Fresh blood samples from healthy humans and Wistar rats were equilibrated with 1, 10, and 30 µM isosteviol at 37 °C in a shaking dry-bath. The levels of isosteviol in plasma and erythrocytes partitions were determined in these samples, after separation, at intervals over a 60-minute period. The data derived was used to estimate erythrocyte-to-plasma and blood-to-plasma coefficients.

Results

Mean erythrocyte-to-plasma partition coefficients (SD) after 60 minutes of equilibration were observed to be 0.039 (0.002) and 0.040 (0.003) in humans and rats, respectively. Derived values for the blood-to-plasma ratio (SD) were 0.576 (0.001) in humans and 0.543 (0.007) in rats, whereas plasma component binding was estimated to be more than 96%.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that isosteviol preferentially partitions into plasma compartments in humans and rats. The significance of this profile for the efficacy, tissue uptake, and retention of isosteviol will have to be further studied.

Introduction

Isosteviol is a synthetic derivative of steviol glycosides that has been the focus of several studies in recent times owing to pharmacologic effects associated with it. Neuroprotective attributes in cerebral ischemia model1 and the attenuation of action potential in hypertrophied cardiomyocytes2 are some major findings of potential clinical significance that have been reported recently. Although these properties have also been associated with steviol glycosides,3 a combination of poor intestinal absorption, extensive metabolism,4 and a much-debated genotoxicity5 limits the therapeutic usefulness of isosteviol's glycosides. Preliminary studies with isosteviol suggest promising benefits because of its reasonable absorption6 with no documented genotoxicity issues previously associated with steviol glycosides.2

A pharmacokinetic study of isosteviol in rats, utilizing plasma, by Jin et al6 observed that a mean peak level of 4.24 µg/mL (∼13 µM) was reached within 15 minutes of oral administration of a 4 mg/kg dose. Mean half-life values were also reported to be 150.6 minutes and 169.9 minutes after single intravenous and oral doses, respectively. Although plasma is a popular biological fluid of choice for pharmacokinetic sample analysis, the erythrocyte-partitioning and plasma-protein-binding properties of drug molecules help provide better physiological description of plasma-derived pharmacokinetic parameters.7 A better understanding of the disposition of isosteviol would benefit immensely from a clearer understanding of its interaction with blood components. In addition, data on isosteviol's partitioning into erythrocytes will serve to reinforce or weaken considerations for potential hematotoxicity in the course of its development as a therapeutic candidate in future.

This study, therefore, investigated the distribution of isosteviol in blood compartments to provide parameters describing its erythrocyte-partitioning and plasma–protein-binding potential in humans and a preclinical animal.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation

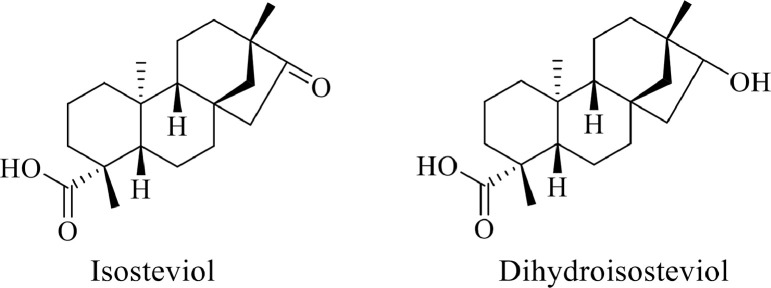

Stock solutions of isosteviol (Figure 1) (purchased from Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide. The internal standard, dihydroisosteviol (Figure 1), was synthesized in-house and its stock solution was prepared in LC-MS grade methanol.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of isosteviol and the internal standard, dihydroisosteviol.

Whole blood samples were drawn from 6 healthy human volunteers, and from healthy Wistar rats (n = 6). Plasma and erythrocytes of humans and rats were separated by centrifugation of whole blood collected in K2-EDTA bottles at 9391 xg for 10 minutes. These matrices were used for the preparation of calibration curves in the range of 0.05 µM to 25 µM for isosteviol. The cellular and plasma fractions were spiked accordingly and vortexed for 1 minute. One hundred microlitre aliquots of spiked plasma samples were protein-precipitated with 400 µL ice-cold methanol (MH) containing 0.3 µM dihydroisosteviol (internal standard). The mixture was briefly vortexed for 1 minute and thereafter centrifuged at 9391 xg for 10 minutes to separate the clear, protein-free, supernatant for LC-MS/MS analysis. Further, spiked erythrocytes were lysed by storage at –80 °C for 24 hours followed by a return to room temperature before a similar protein precipitation with cold MH spiked with the internal standard. Vortex mixing and sample centrifugation was similarly carried out before further analysis.

Erythrocyte partitioning of isosteviol was determined in fresh human or rat blood samples. Packed cell volume (44% and 48% in human and rat samples, respectively), used as a surrogate for hematocrit values of these samples, was determined by centrifugation. Whole blood samples were preincubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C before being spiked with isosteviol to final concentrations of 1 µM, 10 µM, and 30 µM in triplicate, in 1 mL as final volume. These samples were further kept at 37 °C in a shaking dry-bath (Allsheng, Zhejiang, China). Subsequently, aliquots were sampled for centrifugation at 9391 xg for 10 minutes after 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes of incubation with shaking. Plasma and erythrocyte samples were treated as described earlier before analysis. Extracts from incubation at 30 µM isosteviol were diluted 1:3 with distilled water before analysis. Analytes recovered from the incubation of erythrocytes with 1 µM isosteviol were concentrated to 4 times their initial concentration under vacuum at 25 °C.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Isosteviol in human and rat samples was analyzed with a Xevo TQ-S mass spectrometer (Waters; Milford, Massachusetts) connected to an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters) via an electrospray ionization interface. Chromatographic separation of analytes was done with an ACQUITY BEH C18 column (Waters) (3.0 × 50 mm i.d.; 1.7 µm particle size) at 40 °C with samples injection from an autosampler at 15 °C. The mobile phase comprised 5 mM ammonium acetate (AA) and MH pumped through the column in a gradient over a 10-minute period after a 5 µL sample injection. Analyte resolution was achieved by initially pumping a 50:50 ratio of AA:MH through the column for 4 minutes followed by a switch to 25:75 ratio of AA:MH for 2 minutes. The mobile phase was then switched to a 10:90 ratio of AA:MH for 1 minute and then returned to the initial ratio of 50:50 for another 3 minutes.

Data acquisition from the Xevo T-QS mass spectrometer was done in the negative mode to monitor a transition of m/z 317.21 → 273.22 (cone voltage 20 V, collision energy 28 eV) for isosteviol. A transition of m/z 319.21 → 319.21 (cone voltage 30 V, collision energy 15 eV) was monitored for the internal standard as a suitable fragment could not be found. Source and desolvation temperatures were set at 150 °C and 500 °C, respectively. A further scan of samples in the MS1 mode was carried out to detect the likely production of metabolites of isosteviol.

Data analysis

The partition coefficient of isosteviol in erythrocyte, Ke/p, was calculated as a ratio of the concentration of isosteviol in the erythrocyte fraction (Ce) to that of its concentration in the plasma fraction (Cp) (Equation 1). Whole blood-to-plasma concentration ratio, Kb/p, was thereafter calculated using the relationship expressed in Equation 2 where Hc is the hematocrit. Furthermore, it was assumed that only protein-free, unbound, isosteviol molecules could interact/partition into erythrocytes. Hence, the degree of plasma compartment binding in 60 minutes of incubation (fb,60 min) was estimated from the whole blood-to-plasma ratio, and haematocrit using the relation expressed in Equation 37, 8 with Cp and Cb being the concentrations of isosteviol in plasma and blood, respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Results

The assay parameters are summarized in Table 1. Isosteviol was eluted at 6.34 minutes, while the internal standard has a retention time of 6.66 minutes. The limits of detection were 0.056 µM and 0.055 µM in human and rat plasma, respectively, with corresponding quantitation limits of 0.171 µM and 0.168 µM. In erythrocytes, the detection limits observed were 0.043 µM and 0.048 µM in human and rat samples, respectively, with corresponding assay quantitation limits of 0.129 µM and 0.145 µM. Back-calculated concentrated of calibration standards for plasma and erythrocyte samples were all less than ±15% of corresponding nominal values. An MS1 scan of isosteviol samples after 1-hour incubation in fresh blood showed that no detectable metabolite was formed. Data acquired for the partitioning of isosteviol into blood compartments is summarized in Table 2. In human blood, Ke/p values (%CV) of 0.037 (14.54), 0.038 (7.97), and 0.034 (4.69) were observed after 60 minutes of 1 µM, 10 µM, and 30 µM isosteviol incubation, respectively. For rats, Ke/p (%CV) were 0.046 (48.71) and 0.047 (44.41) at 1 µM and 10 µM isosteviol concentrations, respectively, after 60 minutes of incubation at 37 °C.

Table 1.

Summary data regarding analysis of isosteviol in biological matrices.

| Isosteviol concentration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 0.25 µM | 1.5 µM | 5 µM | 25 µM |

| Plasma | ||||

| Within-run imprecision | 2.04 | 3.32 | 0.24 | 1.25 |

| Between-run imprecision | 2.52 | 7.03 | 5.51 | 3.01 |

| Absolute recovery in % [CV %] | 89.54 [2.41] | 88.77 [1.97] | 80.33 [5.14] | 86.55 [3.55] |

| Erythrocytes | ||||

| Within-run imprecision | 3.96 | 4.29 | 0.42 | 0.72 |

| Between-run imprecision | 6.21 | 12.85 | 2.98 | 2.17 |

| Absolute Recovery in % [CV %] | 97.31 [3.92] | 102.32 [2.69] | 93.88 [0.64] | 77.59 [4.01] |

| Rat | ||||

| Plasma | ||||

| Within-run imprecision | 4.01 | 4.63 | 1.94 | 0.64 |

| Between-run imprecision | 7.96 | 7.34 | 5.20 | 4.28 |

| Absolute Recovery in % [CV %] | 91.16 [3.61] | 87.65 [2.73] | 88.77 [2.62] | 88.13 [1.50] |

| Erythrocytes | ||||

| Within-run imprecision | 4.06 | 5.20 | 1.77 | 1.11 |

| Between-run imprecision | 8.26 | 8.42 | 1.49 | 3.12 |

| Absolute Recovery in % [CV %] | 88.79 [3.98] | 86.50 [2.51] | 80.82 [2.44] | 89.31 [1.62] |

All parameters were generated from 6 replicate samples; CV: coefficient of variation.

Table 2.

Summary data of erythrocyte partitioning of isosteviol in human and rat blood.

| Concentration, µM | Mean for 0–60 min (%CV) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ke/p | Kb/p | fb,60 min | |

| Human | |||

| 1 | 0.037 (14.54) | 0.576 (0.23) | 0.971 (0.27) |

| 10 | 0.038 (7.97) | 0.576 (0.21) | 0.950 (0.42) |

| 30 | 0.034 (4.69) | 0.575 (0.12) | 0.966 (0.30) |

| Rat | |||

| 1 | 0.046 (48.71) | 0.542 (2.00) | 0.972 (1.24) |

| 10 | 0.047 (44.41) | 0.543 (1.87) | 0.963 (1.79) |

| 30 | 0.072 (33.75)* | 0.555 (2.10) | 0.947 (1.92) |

fb,60 min = estimated fraction of isosteviol bound to plasma compartments in 60 minutes. Kb/p = whole blood-to-plasma ratio; Ke/p = erythrocyte partition coefficient.

Unusual change likely due to saturation at plasma-binding-sites in rat blood.

Discussion

The model adopted in this study provides information on the extent of binding or uptake of isosteviol into cells, and perhaps tissues, using the erythrocyte as a reference compartment. The results obtained suggests that isosteviol preferentially interacts with human plasma compartments than those of erythrocytes as shown by erythrocyte-to-plasma partition coefficient values of less than 1.0 at all concentrations studied. It is logical to assume that this could only have arisen from a significant binding of isosteviol to plasma proteins that constitute a significant portion of the plasma compartment.

Estimated mean (SD) values of bound isosteviol molecules after 60 minutes of incubation, fb,60 min (Table 2) in human blood was observed to be 0.96 (0.01), and in a manner that was independent of concentration in the range studied. The estimated high binding of isosteviol in human plasma may not necessarily correspond to similar behavior in human tissues as shown with certain drugs like imipramine.9 A greatly reduced unbound concentration of isosteviol in the blood as predicted from this calculation could portend reduced efficiency of its removal by glomerular filtration and other kidney transport systems, and a reduced overall rate of elimination in humans.10 This assumption precludes the possibility of an efficient hepatic biotransformation whose generation of polar metabolites might lead to an increased elimination rate of isosteviol should fb,60 min represent the true value of the amount of isosteviol bound to plasma protein.

Considering the acidic nature of isosteviol and the tendency that it exists in its anionic form at physiological pH, human serum albumin known for its preference for similar anionic drugs11 seems the most probable protein of interest for isosteviol studies. Being a molecule in development, it is important that detailed albumin–isosteviol studies be considered to determine its binding site and kinetics. This will be needed to inform on likely drug-displacement interactions at protein levels that have been reported for similar anionic drugs like salicylates, phenylbutazone, and indomethacin.12, 13 Further, the likely future trial of isosteviol as a therapeutic agent to address cardiac hypertrophy2 will probably require its modeled administration over a period of time. This will often require that toxicity arising from drug-displacement interactions, in likely instances of its potential coadministration with other interventions, is adequately considered.

Although the estimated partitioning of isosteviol into plasma compartments appeared consistent and similar in humans and rats (fb,60 min of 0.97 [0.01] in rat vs 0.96 [0.01] in humans), Ke/p values varied in a time-dependent manner in rats as shown by the larger coefficients of variation reported in Table 2. The in vitro model for Ke/p determination offers rapid equilibration of drug with biological matrix as an advantage over the in vivo technique. This equilibration, however, appears to be slower for isosteviol in rat samples. Further, a sharp increase in mean Ke/p values (∼0.047 vs 0.072) was observed at 30 µM isosteviol concentration in rat blood. This is believed to have resulted from the predominating influence of other interactions at high isosteviol concentration in rat blood where the erythrocyte surface charge is higher14 but plasma volume and serum albumin15, 16 content are less compared with human blood. This interspecies differences in blood-component characteristics may also explain the varied equilibration pattern of isosteviol in human and rat blood. In addition, the authors hypothesize that the saturation of protein binding sites at high concentration in rat blood may have also favoured an increased influx of isosteviol into erythrocytes, leading to the observed increase in Ke/p.

A study of the disposition of isosteviol after single oral and intravenous doses by Jin and et al6 reported a mean volume of distribution of 68 mL in rats with average body weight of 319 g. Assuming a multiple frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis value of 0.96917 and an intracellular water fraction of 0.6,18 the volume of extracellular water would be approximately 123 mL in the animals studied. The volume of distribution of isosteviol from plasma studies reported by Jin et al6 would, hence, amount to about 56% of extracellular water in rats. Although a reference value for isosteviol's steady-state volume of distribution in rats is unavailable, it is most likely that such values will be significantly lower than extracellular water volume in rats, reflecting the extensive partitioning of isosteviol into plasma compartments predicted in the present study.

At the moment, the precise biological target of isosteviol is unknown. Hence, the extent to which its partitioning into plasma compartments might affect its efficacy would most likely be influenced by the location of such targets. The profile of isosteviol in blood compartments presented in this study would likely be most critical if receptors at intracellular sites are needed for therapy. This is because only free molecules would be able to access such sites. It is noteworthy that the contributions of other biological factors such as active transport and dissociation rate of protein-bound molecules might also be very important for the overall efficacy of isosteviol.

Conclusions

The present study identified a preferential partitioning of isosteviol into plasma compartments of the blood in humans and rats. Although the potential for isosteviol-induced hematotoxic events looks unlikely, drug interactions at blood protein binding sites might be very important for its safe coadministration with other agents.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayorinde Adehin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Keai Sinn Tan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Wen Tan: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Validation.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have indicated that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

Contributor Information

Ayorinde Adehin, Email: ayoadehin@outlook.com.

Wen Tan, Email: went@gdut.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Hu H., Sun X., Tian F., Zhang H., Liu Q., Tan W. Neuroprotective Effects of Isosteviol Sodium Injection on Acute Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/1379162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan Z., Lv N., Luo X., Tan W. Isosteviol prevents the prolongation of action potential in hypertrophied cardiomyoctyes by regulating transient outward potassium and L-type calcium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1859:1872–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma J., Ma Z., Wang J., Milne R.W., Xu D., Davey A.K., Evans A.M. Isosteviol reduces plasma glucose levels in the intravenous glucose tolerance test in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:597–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geuns J.M., Buyse J., Vankeirsbilck A., Temme E.H. Metabolism of stevioside by healthy subjects. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:164–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urban J.D., Carakostas M.C., Brusick D.J. Steviol glycoside safety: is the genotoxicity database sufficient? Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;51:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin H., Gerber J.P., Wang J., Ji M., Davey A.K. Oral and i.v. pharmacokinetics of isosteviol in rats as assessed by a new sensitive LC-MS/MS method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48:986–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinderling P.H. Red blood cells: a neglected compartment in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:279–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunt E., Limberg J., Derendorf H. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay and erythrocyte partitioning of fleroxacin, a new fluoroquinolone antibiotic. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1990;8:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(90)80008-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodie B.B., Bernstein E., Mark L.C. The role of body fat in limiting the duration of action of thiopental. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1952;105:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillette J.R. Overview of drug-protein binding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1973;226:6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb20464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang F., Zhang Y., Liang H. Interactive association of drugs binding to human serum albumin. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:3580–3595. doi: 10.3390/ijms15033580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Done A.K. Perinatal pharmacology. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1966;6:189–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.06.040166.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anton A.H. The relation between the binding of sulfonamides to albumin and their antibacterial efficacy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1960;129:282–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da SilveiraCavalcante L., Acker J.P., Holovati J.L. Differences in Rat and Human Erythrocytes Following Blood Component Manufacturing: The Effect of Additive Solutions. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42:150–157. doi: 10.1159/000371474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaias J., Mineau M., Cray C., Yoon D., Altman N.H. Reference values for serum proteins of common laboratory rodent strains. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2009;48:387–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitt D.G., Levitt M.D. Human serum albumin homeostasis: a new look at the roles of synthesis, catabolism, renal and gastrointestinal excretion, and the clinical value of serum albumin measurements. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:229–255. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S102819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornish B.H., Thomas B.J. Measurement of extracellular and total body water of rats using multiple frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis. Nutrition Research. 1992;12:657–666. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasumura S.G.D., Kalef-Ezra J., Xatzikonstantinou J., LoMonte A.F., Yeh J.K., Moore R.I. Distribution of Body Water in Rats. In: Yasumura S., Harrison J.E., McNeill K.G., Woodhead A.D., Dilmanian F.A., editors. Vol. 55. Basic Life Sciences; 1990. pp. 357–360. (In Vivo Body Composition Studies). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]