Abstract

Response to immune checkpoint therapy can be associated with a high mutation burden, but other mechanisms are also likely to be important. We identified a patient with metastatic gastric cancer with meaningful clinical benefit from treatment with the anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody avelumab. This tumor showed no evidence of high mutation burden or mismatch repair defect but was strongly positive for presence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encoded RNA. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas gastric cancer data (25 EBV+, 80 microsatellite-instable [MSI], 310 microsatellite-stable [MSS]) showed that EBV-positive tumors were MSS. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests showed that: 1) EBV-positive tumors had low mutation burden (median = 2.07 vs 3.13 in log10 scale, P < 10-12) but stronger evidence of immune infiltration (median ImmuneScore 2212 vs 1295, P < 10-4; log2 fold-change of CD8A = 1.85, P < 10-6) compared with MSI tumors, and 2) EBV-positive tumors had higher expression of immune checkpoint pathway (PD-1, CTLA-4 pathway) genes in RNA-seq data (log2 fold-changes: PD-1 = 1.85, PD-L1 = 1.93, PD-L2 = 1.50, CTLA-4 = 1.31, CD80 = 0.89, CD86 = 1.31, P < 10-4 each), and higher lymphocytic infiltration by histology (median tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte score = 3 vs 2, P < .001) compared with MSS tumors. These data suggest that EBV-positive low–mutation burden gastric cancers are a subset of MSS gastric cancers that may respond to immune checkpoint therapy.

Immune checkpoint therapy can lead to prolonged durable responses or clinical benefit in multiple cancer types, including advanced gastric cancer (1). However, sustained response with clinical benefit is only seen in a minority of patients. Thus, there is a clear need to identify biomarkers of response and resistance to better select patients most likely to benefit from such therapy.

A high tumor mutation burden (2) from either exogenous carcinogen exposure (3–5,6) or endogenous defects in DNA repair or replication (7,8), is associated with response to immune checkpoint therapy. However, a high mutation burden is not the only mechanism of inducing local immune activation. The presence of certain tumor-associated viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), may also lead to a local immune response (9,10) that may require induction of immune checkpoints (11–13) for tumor survival.

Our hypothesis is that EBV-positive gastric tumors that are microsatellite stable (MSS) with low mutation burden but have evidence of immune infiltration and high expression of immune checkpoint genes are likely to benefit from immune checkpoint therapy. This hypothesis is based on the case study described below.

A woman age 53 years presented with hematemesis, and endoscopy revealed a gastric mass. Biopsy showed a poorly differentiated, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–nonamplified adenocarcinoma with lymphoepitheliomatous histology. Staging revealed retroperitoneal adenopathy, without evidence of metastatic disease (14). She underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection of a poorly differentiated 7 cm adenocarcinoma with positive margins and 21 of 22 lymph nodes involved with metastases (stage IIIC) (14). She received adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Imaging 16 months after surgery showed local and distant disease recurrence with 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG)-avid mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and esophageal biopsy demonstrated adenocarcinoma. She received chemotherapy with cisplatin and irinotecan, with some response. After seven months, she was switched to paclitaxel with ramucirumab. Fifteen months later, the patient presented with severe dysphagia, and imaging showed an increase in her esophageal mass and increasing lymphadenopathy. She was hospitalized for poor oral intake and placement of a jejunostomy feeding tube. She was referred to the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (RCINJ) and, with informed consent, enrolled in an institutional review board–approved trial (NCT01772004) involving treatment with the anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab, given at 10 mg/kg every two weeks. The patient also provided informed consent to participate in the RCINJ genomic tumor profiling protocol (NCT02688517).

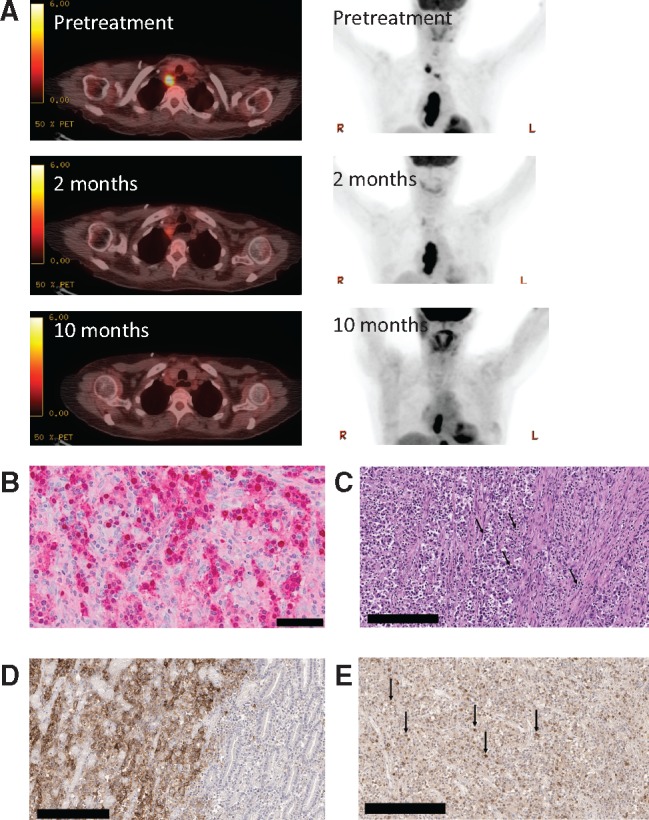

At first restaging scan (Figure 1A), improvement in her esophageal mass and mediastinal adenopathy was noted. As treatment continued, she experienced marked improvement of dysphagia, reduction in esophageal mass, and resolution of mediastinal adenopathy (Figure 1A), and received treatment for more than 24 cycles. Sequencing of the primary tumor using a hybrid-capture-based platform (15) showed a PIK3CA hotspot mutation (E545K), an ARID1A frameshift mutation (N1203fs*3), and PTEN loss. The overall tumor mutation burden was low and inconsistent with the presence of MMR or POLE proofreading defects. Both PIK3CA (16) and ARID1A (17) are often mutated in gastric cancer, and their comutation is frequently observed in EBV-positive gastric adenocarcinoma (16). An EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) assay showed strong positive staining, consistent with the tumor harboring EBV infection (Figure 1B). Tumor histology was consistent with a lymphoepitheliomatous gastric cancer with abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (Figure 1C). By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells demonstrated expression of PD-L1 (Figure 1D), and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the same sample had expression of PD-1 (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Histologic, radiologic, and genomic characteristics of a patient with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive gastric cancer responding to the anti–programmed death–ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody therapy avelumab. A) Representative positron emission tomography–computerized tomography images taken prior to treatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody and two months and 10 months after initiation of therapy. B) Staining of primary tumor for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) is shown in red. Normal gastric mucosa on the slide serves as an internal negative control (not shown). Scale bar = 50 μm. C) High-power image of the original gastric biopsy shows intense infiltrate of lymphocytes within the tumor (black arrows in the center) and associated stroma (black arrow to the right; hematoxylin and eosin ×400). Scale bar = 200 μm. D) Immunostaining of the gastric biopsy sample using the Ventana SP142 for PD-L1 antibody. Gastric adenocarcinoma with 100% staining of malignant cell in a membranous pattern (ie, only the peripheral cytoplasmic membrane stains for the marker and the nucleus and cytoplasm are unstained) for anti-PD-L1 (left portion of image). Bordering benign gastric mucosa shows complete absence of anti PD-L1 staining (right portion of image). The negative control omitting the anti-PD-L1 antibody showed no evidence of staining. Scale bar = 200 μm. E) Of the numerous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes identified, 50% stain strongly positive for PD-1 expression (black arrows) using the OriGene PD-1 UltraMAB antibody. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Gene expression and mutation data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) gastric cancer cohort were analyzed, and tumors were classified into three tumor groups: 1) EBV-positive (EBV, n = 25), 2) microsatellite instable (MSI, n = 80), and 3) the rest (MSS, n = 310). EBV positivity and microsatellite instability were mutually exclusive.

Methods are detailed in the Supplementary Methods (available online). Quantitative statistical data are in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). All P values reported are from two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, except for P values provided by CIBERSORT (18). P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant in all statistical comparisons.

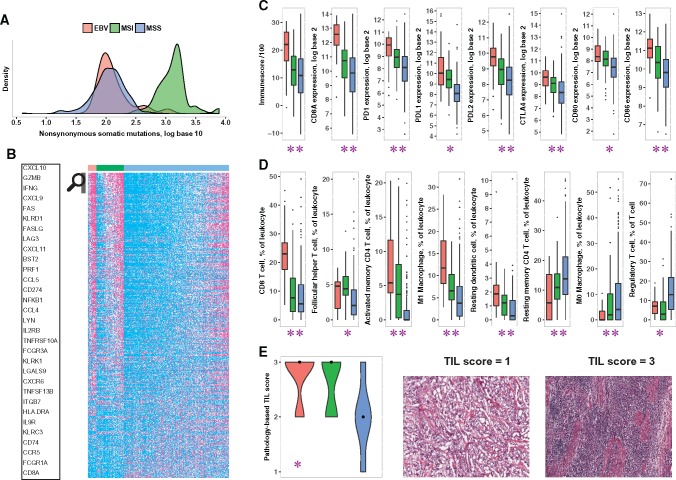

EBV-positive tumors had a nonsynonymous mutation burden comparable with that of MSS tumors in log10 scale (median = 2.07 vs 2.06, P = .71), an order of magnitude lower than in MSI tumors (median = 2.07 vs 3.13, P < 10-12) (Figure 2A). RNA-seq data showed that EBV-positive tumors have higher expression (false discovery rate < 0.01) of most immune-related genes compared with MSS tumors, whereas MSI tumors have an intermediate phenotype (Figure 2B;Supplementary Table 2, available online). Consistent with previous reports (9,10), overall immune infiltration into the tumor, by the ESTIMATE algorithm (19), and expression of T cell marker CD8A were statistically significantly higher in EBV-positive compared with MSI tumors (median ImmuneScore = 2212 vs 1295, P < 10-4; CD8A: log2 fold-change [L2FC] = 1.85, P < 10-6) and in MSI tumors compared with MSS (median ImmuneScore = 1295 vs 1089, P = .04; CD8A: L2FC = 0.86, P < .001) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Comparison of immune markers and mutation burden in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive (red), microsatellite-instable (MSI; green), and microsatellite-stable (MSS; blue) tumors of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) gastric cancer cohort. The results shown here are in whole or part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/. A) Distribution of nonsynonymous somatic mutation burden (in log10 scale) in the three classes. B) Expression (percentile) of immune-related genes differentially expressed (false discovery rate < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction) between the three classes pairwise. For each gene, samples with expression level in the bottom half (0%–50%) are colored cyan, those in the top quartile (75%–100%) are colored magenta, and the rest (50%–75%) are colored white. The genes in the heat map were sorted in descending order for the quantity x = (mean expression in EBV+ - mean expression in MSS) + (mean expression in MSI - mean expression in MSS). The names of a few genes with the highest x values are highlighted. The complete data used in the figure are in Supplementary Table 2 (available online). C) Expression of immune checkpoint genes PDCD1 (“PD-1”) and CTLA-4, their ligands, T cell marker CD8A, and overall immune infiltration (“ImmuneScore”) in the three classes. D) Level of CD8+ T cells, follicular helper T cells, activated and resting memory CD4 T cells, M1 and M0 polarized macrophages, and resting dendritic cells as a fraction of infiltrating leukocytes, as well as proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) among all T cells, in the three classes. All pairwise P values are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (available online). E) Pathology-based Lymphocyte Infiltration Scores in the three classes on a 1 (low) to 3 (high) scale, as represented in the images to the right. These images have no scale bar because they were obtained from the TCGA Digital Slide Archive, which provided no scale (21). In (C–E), ** means EBV+ values are statistically significantly different from both MSI and MSS, and * means EBV+ values are statistically significantly different from MSS but not from MSI. Number of samples: 25 EBV+, 69 MSI, 277 MSS (A); 25 EBV+, 80 MSI, 310 MSS (B, C); 23 EBV+, 58 MSI, 189 MSS (D); 17 EBV+, 13 MSI, 16 MSS (E). The number of samples is different in (A) and (B, C) because for some samples expression data were available but mutation data were not, or vice versa. For samples shown in (B, C) but not in (D), CIBERSORT provided P values of .05 greater. Boxplots (C, D) use the following convention: the horizontal line represents the median value, the box covers the interquartile range (IQR), the whiskers cover values within 1.5 IQR beyond the box, and values beyond 1.5 IQR are represented as dots. In violin plots (E), the black dots mark the median of each class. EBV = Epstein-Barr virus; MSI = microsatellite-instable; MSS = microsatellite-stable; TIL = tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte.

Compared with MSS tumors, EBV-positive and MSI tumors had statistically significantly higher expression of immune checkpoint genes PD-1 (L2FC = 1.85, P < 10-5; L2FC = 0.85, P < 10-4) and CTLA-4 (L2FC = 1.31, P < 10-5; L2FC = 0.78, P < 10-5), and their ligands PD-L1 (L2FC = 1.93, P < 10-7; L2FC = 1.33, P < 10-13), PD-L2 (L2FC = 1.50, P < 10-6; L2FC = 0.70, P < 10-4) , CD80 (L2FC = 0.89, P < 10-4; L2FC = 0.67, P < 10-4), CD86 (L2FC = 1.31, P < 10-6; L2FC = 0.54, P < .001). EBV-positive tumors also had statistically significantly higher expression of PD-1 (L2FC = 1.00, P = .009) and PD-L2 (L2FC = 0.81, P = .005) compared with MSI tumors (Figure 2C). Consistent with this, recent immunohistochemistry studies (11–13) have reported PD-L1 expression in a large fraction of EBV-positive and MSI tumors. Concordantly, PD-L1 expression was strongly positive in our patient’s tumor (Figure 1D).

EBV-positive tumors had a higher proportion of CD8+ T cells by CIBERSORT (18) compared with MSI and MSS tumors. Both EBV-positive and MSI tumors had evidence of higher proportions of follicular helper T cells, and a lower fraction of regulatory T cells, compared with MSS tumors (Figure 2D). In addition, EBV-positive tumors had a higher proportion of activated memory CD4+ T cells, M1 polarized macrophages, and resting dendritic cells compared with MSI and MSS tumors (Figure 2D). Although EBV-positive and MSI tumors may represent two distinct mechanisms of immune activation (via exogenous virus and high mutation burden, respectively), they are almost identical in terms of immune signature.

Pathological evaluation of histological TCGA images showed that EBV-positive and MSI tumors had statistically significantly higher tumor lymphocytic infiltration compared with MSS tumors (median = 3 vs 2, P < .001; median = 3 vs 2, P = .01, respectively) (Figure 2E), confirming previous reports that EBV-positive gastric cancers have robust immune infiltrates (9,10).

Our observations suggest that at least two separate classes of gastric tumors may respond to immune checkpoint therapy: EBV-positive tumors with low mutation burden and MSI tumors with high mutation burden. Our data lend support to the role of immunotherapy in EBV-associated cancers and support the rationale for trials of checkpoint blockade in EBV-positive gastric cancer patients in the absence of high mutation burden. Recent data showing response to pembrolizumab in EBV-associated NK–T cell lymphoma support this concept (20). Because this communication is based on observations in one patient, supplemented by analysis of TCGA data, our findings should be further tested in prospective clinical trials.

Funding

This research was supported by the Biospecimen Repository Shared Resource(s) of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (P30CA072720) and a generous gift to the Genetics Diagnostics to Cancer Treatment Program of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and RUCDR Infinite Biologics. Avelumab was supplied by Merck EMD Serono.

Notes

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions: AP designed the experiments and performed computational analyses; JMM drafted the manuscript, identified and treated the patient, designed experiments, and interpreted data; KH provided direction on the scope of the analyses, interpreted data, and edited the manuscript; GR analyzed histologic data; SD was involved in patient care; TS managed data for this trial; MK was involved as a pharmacist on the study and reviewed the manuscript; LS performed analyses of radiologic evidence; MNS provided direction on the scope of the analyses and was involved in patient care; EP provided patient care; LRR provided direction on the scope of the analyses and edited the manuscript; AWS provided patient care and edited the manuscript; JA participated in care and manuscript review; NC was involved as a co-PI on the trial and in patient accrual; JM was involved in patient care and edited the manuscript; MF was involved in patient care; HLK provided direction on the scope of the analyses and edited the manuscript; SA performed computational analyses; JSR acquired data and performed data analyses; EPW provided direction on the scope of the analyses; GB designed the experiments and performed computational analyses; SG drafted the manuscript, designed experiments, and interpreted data. All authors have reviewed and approved the content in this manuscript.

Conflicts of interests: No conflicts of interest (AP, KH, GR, SD, TS, MK, LS, MNS, EP, LRR, NC, JM, MF, EW, GB). JMM: Honoraria for advisory board member from Merck Sharp and Dohme, EMD Serono, and Roche; has clinical trial funding from Amgen, EMD Serono, Novartis, Polynoma and Merck. AWS: Author has clinical trial funding from Merck and Prometheus Laboratories. JA: Honoraria for Participation in DSMC for Bristol Myers Squibb and Honoraria for Participation in DSMB for EMD-Serono; honorarium for participation in Oncology Panel for Ethicon. HLK: Author serves on a scientific advisory board and a speaker’s bureau for Merck & Co, Inc. (funds returned to Rutgers University); serves on scientific advisory boards for Alkermes, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Prometheus; provides consulting services for Sanofi; has clinical trial funding from Amgen, EMD Serono, Prometheus, Viralytics. SA: Author is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. JSR: Author is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. SG: Author serves on a scientific advisory board and as consultant to Inspirata, Inc., and has equity in Inspirata, Inc.; serves on advisory board for Novartis Pharmaceuticals; has patents on digital imaging technology licensed to Inspirata, Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Muro K, Chung HC, Shankaran V et al. , Pembrolizumab for patients with PD-l1-positive advanced gastric cancer (KEYNOTE-012): A multicentre, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;176:717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T et al. , Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;38710031:1909–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T et al. , Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;37123:2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B et al. , Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;3506257:207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson DB, Frampton GM, Rioth MJ et al. , Targeted next generation sequencing identifies markers of response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;411:959–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A et al. , Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;3486230:124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. , PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;37226:2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mehnert JM, Panda A, Zhong H et al. , Immune activation and response to pembrolizumab in pole-mutant endometrial cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016;1266:2334–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grogg KL, Lohse CM, Pankratz VS, Halling KC, Smyrk TC.. Lymphocyte-rich gastric cancer: Associations with Epstein-Barr virus, microsatellite instability, histology, and survival. Mod Pathol. 2003;167:641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiaravalli AM, Feltri M, Bertolini V et al. , Intratumour T cells, their activation status and survival in gastric carcinomas characterised for microsatellite instability and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Virchows Arch. 2006;4483:344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Derks S, Liao X, Chiaravalli AM et al. , Abundant PD-l1 expression in Epstein-Barr virus-infected gastric cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;722:32925–32932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma C, Patel K, Singhi AD et al. , Programmed death-ligand 1 expression is common in gastric cancer associated with Epstein-Barr virus or microsatellite instability. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;4011:1496–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawazoe A, Kuwata T, Kuboki Y et al. , Clinicopathological features of programmed death ligand 1 expression with tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, mismatch repair, and Epstein-Barr virus status in a large cohort of gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer. 2017;203:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed.New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA et al. , Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;3111:1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;5137517:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang K, Kan J, Yuen ST et al. , Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of ARID1A in molecular subtypes of gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2011;4312:1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR et al. , Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;125:453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E et al. , Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwong YL, Chan TSY, Tan D et al. , Pd1 blockade with pembrolizumab is highly effective in relapsed or refractory NK/T-cell lymphoma failing L-asparaginase. Blood. 2017;12917:2437–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutman DA, Cobb J, Somanna D et al. , Cancer digital slide archive: An informatics resource to support integrated in silico analysis of TCGA pathology data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;206:1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.