Abstract

The National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine sponsored a workshop on July 24 and 25, 2017 on Long-Term Survivorship after Cancer Treatment. The workshop brought together diverse stakeholders (patients, advocates, academicians, clinicians, research funders, and policymakers) to review progress and ongoing challenges since the Institute of Medicine (IOM)’s seminal report on the subject of adult cancer survivors published in 2006. This commentary profiles the content of the meeting sessions and concludes with recommendations that stem from the workshop discussions. Although there has been progress over the past decade, many of the recommendations from the 2006 report have not been fully implemented. Obstacles related to the routine delivery of standardized physical and psychosocial care services to cancer survivors are substantial, with important gaps in care for patients and caregivers. Innovative care models for cancer survivors have emerged, and changes in accreditation requirements such as the Commission on Cancer’s (CoC) requirement for survivorship care planning have put cancer survivorship on the radar. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation’s Oncology Care Model (OCM), which requires psychosocial services and the creation of survivorship care plans for its beneficiary participants, has placed increased emphasis on this service. The OCM, in conjunction with the CoC requirement, is encouraging electronic health record vendors to incorporate survivorship care planning functionality into updated versions of their products. As new models of care emerge, coordination and communication among survivors and their clinicians will be required to implement patient- and community-centered strategies.

Cancer begins and ends with people. In the midst of scientific abstraction, it is sometimes possible to forget this one basic fact. (1)

—June Goodfield as cited in The Emperor of all Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee

N.A. is a 48-year-old male diagnosed with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma at age 25 years while pursuing his PhD studies. He received chemotherapy for three years and radiation to the head and neck. Treatment was deemed successful and he has been in remission for 23 years. But the road through survivorship continued. About 13 years postdiagnosis, he developed congestive heart failure and then three years later experienced a near cardiac arrest leading to the placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Numerous other treatment-related complications ensued, each leading to a new specialist. Despite being an educated researcher, throughout his cancer journey, N.A. has had questions about his diagnoses and has been challenged in trying to understand complex medical information. He has needed help making decisions, longed for emotional support, and faced the daunting task of navigating the health care system, often by himself. He was not a patient treated in a patient-centered, primary care-based medical home, but one in several homes belonging to multiple specialists, not knowing whether his providers were communicating with one another and providing him with quality, coordinated care. He often felt homeless in a world of medical homes. While acutely aware of important efforts being made by researchers to improve health outcomes for cancer survivors, N.A. is increasingly frustrated by the slow pace at which state-of-the-science survivorship research is translated into improvements in the delivery of care for survivors like him.

The experiences of this relatively young cancer survivor are not unusual, and problems associated with cancer survivorship only increase with age. As of 2016, there were more than 15.5 million individuals living with a history of cancer; by 2026, that number is expected to rise to 20.3 million (2). Studies have shown that at least 25% of cancer survivors 65 years and older have five or more comorbid medical conditions (3,4). On average, these survivors are likely to interact with seven or more physicians per year (5).

Estimates of the costs of cancer survivorship vary widely depending on how the term is defined, which costs are included, and which methodologies are used. One study, using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and the SEER-Medicare data linkage, trending forward prevalence data to 2017, estimated medical costs of $57 billion (2010 dollars) when those costs were limited to those starting one year after diagnosis and ending one year before death (6). This same study estimated total medical costs for cancer care in 2010 at $137.4 billion. A different study, using the 2008–2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, estimated medical costs of $90 billion (2010 dollars) when all medical costs between the time of diagnosis and death were included (7). The loss of economic productivity associated with a cancer diagnosis, in addition to medical costs, was estimated at $26 billion, bringing the most comprehensive total of cancer costs in this study to $116 billion (7).

In 2004, the IOM convened a panel to make recommendations for improving the fragmentation and absence of coordinated care for cancer survivors in the United States (3). Since the report was published in 2006, progress has been made across most of the 10 recommendations put forth by the panel; however, important gaps remain (Table 1) (8). The number of cancer survivors continues to grow, yet high-quality, coordinated survivorship care is still infrequent. In particular, cancer survivors have multiple medical conditions, often related to the late and long-term effects of their initial cancer treatment as well as conditions related to premature aging (eg, fatigue, cognitive changes, decreased physical functioning). There remain many opportunities to reduce suffering and mortality among survivors. These include help in returning to life, to work, and to school. These will require the design and implementation of models of care delivery and risk stratification with approaches that are not only disease-focused, but take a whole-person approach to survivorship care by addressing patients’ physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs. Cancer survivors need to be educated about expectations after their treatment ends and how they should be monitored for late effects of cancer treatment. This must be facilitated by ensuring that their clinicians, including the full spectrum of primary care providers and specialists, as well as allied health professionals, have comprehensive education and training about the long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment. In addition, increased attention is required to reduce the burden of informal caregiving across the cancer continuum. Survivorship care needs to be accessible, affordable, and equitable. As the future research and policy agenda is articulated, there remains a need for efforts to accelerate the pace at which evidence-based knowledge is translated into improved clinical practice. The 2017 National Cancer Policy Forum Workshop (9) addressed these topics, which are summarized in the following sections.

Table 1.

2006 IOM recommendations: current progress and future directions*

| Recommendation | Progress | Future Directions |

|---|---|---|

| #1: Health care providers, patient advocates, and other stakeholders should work to raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care. | Growing awareness of cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer in the public. Emergence of textbooks, special reports, survivorship guidelines, and survivorship advocacy organizations. | Continue to raise awareness among survivors and clinicians, particularly in underserved communities. Emphasize the longitudinal path of the survivorship phase, starting at the time of diagnosis and including those who are living with cancer. |

| #2: Patients completing primary treatment should be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan that is clearly and effectively explained. This “Survivorship Care Plan” should be written by the principal provider(s) who coordinated oncology treatment. This service should be reimbursed by third-party payers of health care. | Efforts being made by clinical sites to develop SCPs, but limited by time, effort, and the availability of information. Several toolkits have been developed. Limited evidence for altering or improving care. CoC and OCM have SCP requirements. | Enhance information technology support for developing SCPs and optimize the use of plans by survivors and health care providers. Understand that the SCP is a living document that is modified over time. Reimbursement for completion of SCPs should align with effort. |

| #3: Health care providers should use systematically developed, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. Existing guidelines should be refined and new evidence-based guidelines should be developed through public- and private-sector efforts. | Guidelines now exist for a number of cancer types that address survivorship care in general, as well as more specific symptom-based guidelines. Although mostly consensus-based at this time, there is a growing evidence base in guidelines. Many are available on mobile apps. | Continue evidence generation for the development of guidelines. Incorporate survivorship care needs in disease-based guidelines. Aim for consistency across guidelines, with harmonization efforts nationally and internationally. |

| #4: Quality of survivorship care measures should be developed through public/private partnerships and quality assurance programs implemented by health systems to monitor and improve the care that all survivors receive. | Quality being addressed by ASCO through QOPI, but these measures primarily focus on treatment rather than survivorship. Insurers and health care delivery systems do not appear to be measuring cancer survivorship quality. | Need to identify and develop clinically relevant measures of cancer survivorship and quality of life and function as well as measures of survivors’ care experiences. Research into models of care must consider quality measures and outcomes, such as health care utilization and costs. |

| #5: CMS, NCI, AHRQ, VA, and other qualified organizations should support demonstration programs to test models of coordinated, interdisciplinary survivorship care in diverse communities and across systems of care. | Most research continues to focus on basic science. Limited but growing interest in demonstration projects focusing on cancer survivorship. | CMS is currently testing OCM, which may provide important insights into cancer survivorship care and requires a SCP for appropriate beneficiaries. Need to think beyond current models of care, including multidisciplinary and multi-specialty care approaches. Understand and develop pathways where the intensity of care provided can be tailored to the individual and setting. Promote dissemination of evidence-based interventions. |

| #6: Congress should support Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, other collaborating institutions, and the states in developing comprehensive cancer control plans that include consideration of survivorship care, and promoting the implementation, evaluation, and refinement of existing state cancer control plans. | Most state cancer control plans address survivorship, but proposed objectives are variable. No clear report of measurable progress. The George Washington Cancer Institute created resources to help state programs develop goals and collaborate. | Need to evaluate progress made, learn from states, and disseminate best practices. |

| #7: NCI, professional associations, and voluntary organizations should expand and coordinate their efforts to provide educational opportunities to health care providers to equip them to address the health care and quality of life issues facing cancer survivors. | Educational programs have been developed by professional and community-based organizations. Uptake, particularly by targeted audiences, appears to be limited. | Continue to promote and disseminate multi-disciplinary educational opportunities for providers in primary care, oncology and other subspecialties. |

| #8: Employers, legal advocates, health care providers, sponsors of support services, and government agencies should act to eliminate discrimination and minimize adverse effects of cancer on employment while supporting cancer survivors with short-term and long-term limitations in ability to work. | Progress has been made in research, clinical and policy initiatives pertaining to the recognition of the impact of cancer on employment and financial toxicity. | Continued research initiatives, promotion of discussions in clinical settings, and emphasis on policy/regulations in the work place, promotion of return to work programs and policies. |

| #9: Federal and state policy makers should act to ensure that all cancer survivors have access to adequate and affordable health insurance. Insurers and payers of health care should recognize survivorship care as an essential part of cancer care and design benefits, payment policies, and reimbursement mechanisms to facilitate coverage for evidence-based aspects of care. | Healthcare legislation has addressed many issues for cancer survivors by eliminating preexisting condition exclusions, requiring community rating for insurance, eliminating lifetime caps, allowing patients to remain on their parents’ health insurance until the age of 26 years, and expanding Medicaid. | The permanence of many health law provisions remains uncertain. |

| #10: NCI, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, AHRQ, CMS, VA, private voluntary organizations such as the American Cancer Society, and private health insurers and plans should increase their support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. New research initiatives focused on cancer patient follow-up are urgently needed to guide effective survivorship care. | Growing numbers of studies in survivorship, but gaps in content and focus. Most research is on quality of life. | Need to focus on domains of cancer survivorship and populations that have been understudied. Need to understand the biological pathways for the development of late effects and find mitigating interventions. |

AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ASCO = American Society of Clinical Oncology; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; CoC = Commission on Cancer; NCI = National Cancer Institute; OCM = Oncology Care Model; QOPI = Quality Oncology Practice Initiative; SCP = Survivorship Care Planning; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Physical Well-Being in Cancer Survivorship

The physical after-effects of cancer treatment are myriad. Conceptually, these are often divided into two categories: long-term effects and late effects. Long-term effects of treatment are those that arise during initial treatment and persist after treatment ends. Common examples include pain, physical limitations, fatigue, cognitive difficulties, and sexual problems. Late effects of treatment appear months to years later, are usually experienced as new health problems, and can include lymphedema, hypothyroidism, cardiac or respiratory problems, or secondary malignancies (10). Many cancer survivors have excellent prognoses from treatment of the primary cancer; however, these effects often contribute to increased morbidity, including premature death, in survivorship. Many survivors do not receive the surveillance and preventive interventions necessary to reduce and manage those health risks. As the population of cancer survivors grows, promotion of long-term health needs to be a central goal of care, but widespread assessment and intervention of long-term and late effects in standard care remain limited (11).

Long-Term Effects

When the 2006 IOM report was released, there was little recognition of the prevalence of long-term effects among survivors. A growing body of published literature, as well as guidelines from major cancer organizations such as the American Cancer Society (12–14), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (15–17), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (18), and the Commission on Cancer (CoC) (19) demonstrate progress in this area and have begun to articulate the etiology, prevalence, and management of common long-term effects, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive difficulties. Cancer-related symptom burden that persists for survivors after treatment completion can be substantial, with 27% of off-therapy patients having three or more moderate to severe symptoms (20). Furthermore, poorly controlled symptoms can often lead to reduced quality of life (21), nonadherence to follow-up care (22,23), and lower rates of return to work and/or impaired ability to work (24,25).

Late Effects

With respect to late effects of treatment in cancer patients, data show an increased likelihood of second malignancies and evidence for accelerated aging in many organs, particularly in association with radiation and multi-modality therapies. Approximately 20% of incident cancers each year occur in previously treated cancer patients and represent second, third, or fourth cancers for some individuals. (26–28). Although these additional new cancers may be related to genetic predisposition and cancer treatment exposures, more often they occur as a result of host factors, conditions related to aging and premorbid conditions, and health behaviors (eg, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, obesity, physical inactivity) (27,29,30). When hereditary cancer risks are present, early detection can inform organ-directed surveillance or preventive interventions. Thus, health promotion and preventive activities are essential in the care of cancer survivors to reduce the risks of late effects, including subsequent cancers (31).

Survivorship Care: Barriers and Opportunities

Barriers to symptom control include lack of routine assessment of patient-reported outcomes, failure of effective management for issues that are identified, and limited awareness of relevant guidelines. Treatment modifications (eg, reduced intensity regimens) have emerged as an important strategy to decrease exposures associated with late effects. Steps to mitigate risks of long-term effects, such as screening for premorbid risk factors (eg, preexisting neuropathy) and more effective management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, may be feasible as well. Screening for long-term effects can allow for earlier intervention and management of these concerns as well as risk stratification for intervention. Routine follow-up care should include standardized symptom assessments to facilitate earlier intervention in those with persistent difficulties.

Newer approaches to care delivery, such as those being tested in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Oncology Care Model (OCM) (32), may support the coordinated delivery of evidence-based interventions that target the after-effects of treatment. Close coordination with primary care providers is necessary to address chronic conditions of cancer survivors. For example, standard cardiovascular risk calculators may not apply to cancer survivors. More aggressive and earlier preventive intervention is needed for those with a heightened risk for cardiac injury due to treatment exposures (eg, chest radiation, anthracyclines), and earlier management of hypertension and hyperlipidemia is being recommended (33). Risk prediction models and treatment approaches for other chronic health conditions (eg, osteoporosis) need to be adapted for cancer survivors and widely disseminated among primary care clinicians who care for these individuals.

Early inclusion of rehabilitation services represents another important partnership in survivorship care. Prehabilitation may benefit high-risk patients (eg, frail, elderly, those undergoing complex surgery), and specialized rehabilitation can help survivors in their physical recovery from primary treatments (34,35). Rehabilitation services are especially appropriate for management of the physical needs of survivors, including pain and symptom control, and are reimbursable, as is the inclusion of palliative care services.

Cancer survivors are at risk for recurrence, secondary cancers, comorbidities, functional decline, and poor quality of life and may benefit from behavioral interventions. Although cancer survivors may have similar rates of obesity, physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use, and behavioral patterns as those without cancer (29,36–38), these factors may be more dangerous when coupled with their disease characteristics and treatment exposures. Healthy, cancer-protective behavioral interventions are a key element of good survivorship care, but an adequate workforce of physicians, advanced practice providers, registered nurses, and other allied health professionals with training and expertise in this area does not currently exist. Health insurance plans often do not reimburse for behavioral interventions in this patient population, and this is an important gap to address.

Psychosocial Well-Being and Family Considerations in Cancer Survivorship

The importance of addressing the emotional and social well-being of cancer survivors and their loved ones has been emphasized in previous IOM reports (3,39); however, these aspects of health continue to be overlooked during and after cancer treatment (40). In the “new alternate reality” that is survivorship, as one advocate described life after cancer, healthcare visits can often induce, rather than relieve, psychosocial distress.

Current data suggest that 15% to 20% of adult cancer patients/survivors experience depressive disorders and 10% to 12% exhibit anxiety disorders (41–43). Findings among childhood cancer survivors are largely similar (44,45). Further, risk factors for depression and anxiety are well known, including exposure to specific therapies (eg, taxanes, interferon, bone marrow transplantation) (Table 2) (46,47). Inter-relationships also exist among stress, depressive symptoms, and premature mortality such that lower survival for both cancer and general populations is consistently associated with poor psychosocial well-being (48,49).

Table 2.

| Domain | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Medical |

|

| Personal |

|

| Social |

|

| Caregiver† |

|

A key difference between adult and childhood cancer survivor populations is that children’s adaptation is more tightly linked to their medical late effects. Overall health, pain, disfigurement, and other chronic conditions are consistently found to be associated with poor psychosocial outcomes of all kinds. Young brain tumor survivors and those receiving other CNS-directed therapies fare the worst (40,41).

Although medical/treatment risks do not apply to caregivers directly, personal and social factors that increase risk for survivors are parallel for caregivers, in addition to the unique items listed.

While living apart from a care recipient can be a buffer on strain, if this significantly increases travel/commute time for those needing regular care, this can be a risk factor for burden.

Notably, the past 25 years have seen the development and testing of numerous interventions to address survivors’ distress, albeit directed primarily to adult survivors (50,51). Most interventions have modest effects, in part related to lack of focused recruitment of those who are anxious or depressed. Effect sizes are greater when interventions are targeted to populations with higher needs (ie, those who score at or above the established cut-off for risk on a standardized assessment tool) (52). Key components of successful interventions include education about the cancer, its treatment and effects, and tools to manage symptoms as well as stress reduction techniques (eg, yoga, exercise) (53).

The picture for cancer caregivers, who are often unrecognized members of the survivorship community, looks similar. Caregivers, predominantly women and spouses, report substantial caregiver-related burden, stress and depression, feeling unprepared for the caregiver tasks they perform, and receiving limited training for their role (54–56). Caregivers often balance other life responsibilities (eg, work, caring for children or other adults) (57,58), may have their own health issues, and neglect aspects of self-care (55,56). Further, cancer caregiving (compared with caregiving for other conditions) is more intense and episodic (56). Studies show cancer caregivers’ psychosocial well-being may be interdependent with that of their care recipient such that when one member of the dyad does poorly, so does the other (59). Conversely, interventions that improve the well-being of one can positively influence the function of the other (60).

Opportunities for Change

Several steps can be taken to make progress toward meeting the psychosocial needs of cancer survivors and their caregivers. First is breaking the silence. Reluctance by survivors to discuss their personal concerns, and by providers to ask about these, are key barriers to addressing psychosocial well-being. The current recommendation is to make screening for anxiety and depression, for which patient care guidelines exist (61,62), a routine part of care across the cancer care trajectory. Parallel screening of identified caregivers (for whom risk factors for poor adaptation mirror those of their care recipients) (Table 2) could be added to clinical practice. Future policies could support the proactive identification of at-risk caregivers within the medical setting as a standard of practice (63).

Second, although effective interventions are available, few are broadly applied (64). Greater dissemination and implementation of best practices for screening and intervention are needed across the country and should address diverse survivor populations in a variety of settings (64,65). This will require optimizing existing interventions, expanding outcomes of interest (including those of value to providers, systems, and payers) in program evaluation, and considering the use of eHealth platforms and technologies to permit greater accessibility to services.

Third, better understanding of cancer-related distress vs other life-threatening and potentially chronic conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease, diabetes) is needed. At any given time, approximately 20% to 40% of survivors have increased psychosocial needs (51,62). Most will have mild to moderate symptoms, and there may be multiple problems in many areas (eg, emotional, social, and existential). Further, care is often episodic; a survivor may be fine during active treatment only to become depressed 6 months posttreatment (56,66). Caregivers may be surprised when this occurs, because treatment has ended and the assumption is that everything is fine. In fact, the patient is at a low point, realizing that they will be living with the risk for cancer recurrence and ongoing treatment side effects for an indefinite period of time.

Fourth, determining where and who will deliver this care must also be addressed. With wide variability in the availability and expertise of providers, populations seen, and available resources, one approach will not serve all. Models of integrated care delivery need to be designed and tested in different clinical settings. Provision of survivorship care in the treating clinic, where services are integrated with medical care, may be ideal for some patients. In this setting, trusted staff that understands the treatment the survivor received and associated late effects can see them. For others, this setting may not be appropriate due to distance, lack of appropriately trained staff, or the desire to move away from reminders of the cancer experience associated with the oncology setting. Engaging primary care providers in the coordination and delivery of posttreatment psychosocial care is vital. Whereas some primary care clinicians may feel they are competent to serve in this role, many are anxious about delivering psychosocial care (67,68).

Finally, education is needed to promote awareness of the psychosocial needs of cancer survivors and their caregivers, to provide information on how to best identify and address these needs, and to support efforts to make delivery of these services a seamless part of quality survivorship care. Educational interventions will be needed among all stakeholders in this effort.

Socioeconomic Considerations in Cancer Survivorship

Three broad topics are paramount to any discussion of socioeconomic considerations in cancer survivorship. They are financial hardship, employment consequences of diagnosis and/or treatment, and health insurance affordability and availability, particularly with regard to changes being considered to existing healthcare laws (69).

Cancer survivors face substantial financial burdens of treatment and other related costs, including transportation and forgone wages from reduced working hours, or the inability to work (70–72). The term “financial toxicity” has recently gained traction as a way of framing the economic burden patients and their families endure (73). Considering financial burden as a “toxicity,” along with physical and psychosocial toxicities of treatment, recognizes the impact of financial burdens on patients’ lives, including their health outcomes.

Once acute treatment ends, survivors face ongoing expenses for monitoring and surveillance and may be at risk for job loss or interrupted health insurance, especially if they have had extended absences from work during treatments. Many oral-directed treatments extend for years after acute treatment is complete, and with many newly approved oral antineoplastic agents, we expect these expenses to increase. Considerable evidence suggests nonadherence to prescribed long-term regimens due to cost of medications (74–77). A notable example is discontinuation of hormonal therapy following breast cancer treatment (78). In the survivorship period following completion of treatment, some survivors forgo recommended surveillance and needed medical care, jeopardizing their long-term well-being by not attending to their health care needs and potentially missing recurrent cancers (79). The likelihood of forgoing care is higher among those who are poor, uninsured or publicly insured, and not working (79). This population in particular may suffer disproportionately from financial toxicity resulting from a cancer diagnosis and treatment.

A financial hardship framework has been created that describes the three types of hardship experienced by patients and their families during cancer survivorship, including material (medical debt), psychological (worry about medical bills), and behavioral (delaying or foregoing care) (80). Adding to the psychological hardship is the uncertainty of ongoing or future cancer treatment costs (81). There is no easy, accurate way to provide patients with an estimate of the expected total out-of-pocket expense of their cancer treatment. Clinicians lack information and are not prepared to discuss the cost of care with their patients (82). Vulnerable populations and low-income individuals are less likely to discuss financial issues and may simply forgo treatment, potentially exacerbating disparities in outcomes (83). Once treatment ends, both clinicians and survivors may underestimate ongoing expenses related to health care, especially as comorbid conditions accumulate.

While the need for accommodations during treatment may be clear, employers often lack understanding of issues that persist after treatment completion, such as fatigue, “chemo brain,” and other physical symptoms and side effects such as depression, anxiety, and other psychosocial distress (84). Additionally, employers and co-workers may not understand cancer survivors’ continued needs for time off for follow-up visits and continued surveillance as well as the continued physical and emotional effects of cancer even after treatment is complete.

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 allows up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for an employee’s own health condition or caregiving responsibilities for a family member and applies to all public agencies, all public and private elementary schools, and companies with 50 or more employees. Individual states may impose additional requirements. Small businesses (ie, fewer than 50 workers), however, comprise nearly 90% of businesses and employ approximately 6 million workers (85), making many ineligible for these protections. Unpaid leave is cost prohibitive for many people, especially given the financial burden of cancer treatment.

Availability of health insurance outside of the employment context is another key concern for cancer survivors. Before changes in health care legislation in 2010 (69), many cancer survivors were uninsurable, because their cancer history was considered a preexisting condition and they were generally denied coverage or, in some cases, offered coverage at inflated premiums. Current healthcare laws prohibit insurers from denying coverage or charging higher rates because of health status and prior conditions, which has greatly improved access for cancer survivors. However, the future of these laws and their provisions, including the availability of insurance on the exchange market, mandatory benefits, out-of-pocket limits, and exclusions or differential rates based on preexisting conditions, continue to be a topic that is widely debated.

Survivorship research has not kept pace with the economic aspects of cancer survivors’ needs, perhaps because it is not easy to shift the paradigm from diagnosis and treatment to one focused on minimizing long-term consequences. However, with the discovery of new therapies and early detection, the average cancer survivor can expect to live many years. This is particularly relevant to the growing group of “chronic cancer survivors” who will be on long-term, targeted therapies that often have an exceedingly high cost (86). Prolonged survival, combined with high-cost therapies, makes the mitigation of financial toxicity, work-related consequences, and the potential loss of health insurance all the more relevant.

Models of Survivorship Care Delivery

Survivorship care models have, as an overarching goal, the delivery of comprehensive care that includes medical and psychosocial services, cancer screening, assessment of and intervention for late effects, and healthy living counseling, but they may differ in the type of health care provider, timing of selected services, and type of services provided. To date, the literature documents only a limited number of models that achieve this comprehensiveness, and few have been evaluated for health outcomes. Thus, the establishment of successful, evidence-based survivorship care models remains a work in progress.

Evolving Care Models

Publications on care models highlight the value of team-based approaches to survivorship (87–90). Nurses, especially advanced practice nurses, have had prominent roles in leading survivorship clinics, fulfilling the recommendations of another IOM report, “The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health” (91–94). Major attention has also been placed on the role of primary care clinicians in survivorship care, not only through calls to action, but importantly, through joint educational activities, such as the Cancer Survivorship Symposium, which includes American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians (95).

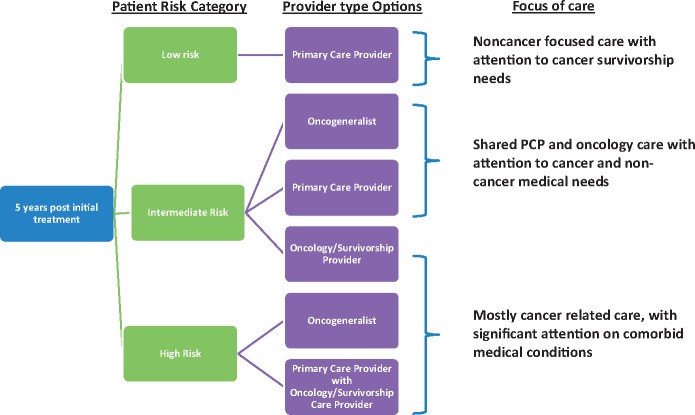

Research has helped to define specific services for unique communities of patients rather than continuing to use the “one-size-fits-all approach” that was initially implemented in formal survivorship clinic models, usually at academic medical centers. This approach has the advantage of being resource and cost efficient by offering the right services to the right patient at the right time. Risk-based models have often been proposed, but they are now part of planning new programs and revising existing care models (96–99) (Figure 1). Distinguishing models of care by risk (low, moderate, and high) allows for the selection of the most appropriate provider as well as the types and frequency of these services. It also provides the opportunity for novel care delivery models that apply self-management concepts, utilize telemedicine to reach underserved survivors, and employ group visit strategies used in other chronic disease models (100,101).

Figure 1.

Modified from Nekhlyudov et al. Lancet Oncology 2017 (98). Risk-based strategy for cancer survivorship care. For the purposes of cancer survivorship care, five years is based on the general recommendations of the cancer community, although the timing of the transition of care may vary. Examples of risk categories include low-risk cancers, which are defined as individuals with common cancers that are treated at an early stage, and/or standard treatment. The noncancer chronic condition burden may be low to high, with the latter potentially benefiting from primary care-based follow-up. Intermediate-risk individuals are those with less common cancers, those treated at an advanced stage, and/or the use of multimodal treatment. As with the low-risk individual, noncancer chronic condition burden may vary. High-risk individuals are those with rare cancers, advanced stages, and those requiring complex medical treatment with important late/long term effects. An oncogeneralist is a primary care provider with expertise in survivorship who can integrate the complex needs of adult cancer survivors. An oncology/survivorship provider is an oncology specialist or provider with cancer survivorship expertise. These providers may be physicians or advanced practice clinicians.

Evaluation and Dissemination of Models

The development of survivorship care models is the first step in a pathway that leads to adoption, and it is critical to include dissemination and implementation assessments early in the development of new models. Evidence-based practice must be contextualized through meaningful adaptation to be successful. Some questions to be considered by researchers and clinicians developing and implementing care models are: can evidenced-based programs and services be adopted, maintained, and sustained over time; are clinicians trained to deliver these programs; will trained providers choose to adopt these programs as part of structured survivorship care; and will eligible survivors have access to and choose to receive survivorship care? Consideration of these elements will assure that new care models are incorporated within health systems. This is the challenge going forward. Methodologies such as the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Research Tested Intervention Program will allow faster adoption of tested interventions into practice (102).

Patient Engagement in Model Design, Delivery, and Evaluation

Survivors are central to improving the design, delivery, and assessment of any approach. Engaging them from the beginning assures that implementation issues are successfully addressed. This can eliminate the false notion that “if we build it, they will come,” and replaces it with the affirmation, “If we build it, we will come.” At the macro level, such engagement addresses the key elements of survivorship services and tools, such as survivorship care plans. From the perspective of the survivor as an end user, care plans are an important decisional tool and a conversation assist, but not an end in themselves. The real value in the survivorship care plan is in the provider and survivor co-creating and implementing a plan together. At the micro level, collaboration with patients and local survivor communities allows customization to meet the specific needs of a geographic area. For example, a unique model of care using a mobile van has been developed for survivors in rural Texas based on survivor input (103). This type of patient- and community-centered strategy is essential to future survivorship care models because they leverage the partnerships necessary for success and sustainability while allowing for ongoing evaluation.

An Agenda to Improve Cancer Survivorship Care

Given the multifaceted challenges of cancer survivorship, the workshop culminated in a discussion of actions stakeholders should take to improve care and quality of life for cancer survivors. Diverse potential solutions were suggested for governmental and private efforts, including professional and accrediting organizations, encompassing changes in medical education, health insurance, and clinical standards and practice, while seeking to protect existing legislative gains. We focus on a few of these opportunities.

Shifting the Focus of Accreditation and Cancer Reporting Programs Towards Survivorship

Rather than creating new accreditation frameworks to place increased emphasis on survivorship, existing structures can be modified to accomplish similar goals. An excellent example is the decision of the CoC to require survivorship care planning as a component of accreditation. The CoC accredits 1500 hospital-based cancer programs in the United States that are responsible for the care of 70% of oncology patients. This requirement placed cancer survivorship “on the radar” in 2012 by requiring hospitals to create and deliver survivorship care plans to patients with stage I to III cancer treated with curative intent beginning in 2015. In 2015, the requirement specified that a minimum of 10% of these patients receive survivorship care plans. This increased to 25% in 2017 and 50% in 2018. Beginning in 2019, programs will need to have a structured survivorship program, including a survivorship coordinator and team, to provide care necessary to optimally support these patients (104).

Other opportunities include changing the public reporting requirements for federally-funded cancer registries to encompass longer time periods, thereby placing an increased focus on survivorship. These registries include NCI-SEER*Explorer (105), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries (106), and North American Association of Central Cancer Registries On-Line Cancer Data (107). The privately funded CoC publishes National Cancer Database Public Benchmark Reports (108), and this organization could also be encouraged to report outcomes that include longer time periods. One specific example is a new requirement under consideration by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research that hematopoietic stem cell transplant programs report patient outcomes at three years (rather than just at 100 days and one year), thus creating a new focus on the late effects of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (109). Reporting of three-year outcomes is already being done by the Health Resources and Service Administration under private contract, although the results are not reported at the center level (110).

Board Certification, Maintenance of Certification, and Graduate Medical Education

There are multiple levers to increase awareness and competence around survivorship issues in the medical education system, including an increased focus on cancer survivorship during initial board certification and maintenance of certification examinations as well as the creation of dedicated fellowship programs or special credentials to acknowledge additional training in this field. The relative benefits of broad-based general education efforts in internal medicine compared with more focused efforts to create fellowship-trained (or credentialed) specialists in this area is a topic of active discussion, with an appreciation that both would improve survivorship care planning, albeit in different ways. Reconciling competing demands among many important areas in medical education and testing remains challenging.

Governmental Efforts

Important protections were achieved for cancer survivors through changes to health care laws in 2010 (69), including protections for cancer survivors by eliminating preexisting condition clauses, mandating community rating regardless of medical history, and eliminating lifetime insurance caps.

Other federal government policy solutions that could improve survivorship care include a requirement for survivorship programs at NCI-designated (and funded) cancer centers and the creation of specialized payment codes to reimburse for survivorship care planning in addition to the time-based codes currently in existence. State legislative efforts can change benefit requirements for cancer survivors to mandate coverage for infertility treatment or behavioral modification treatment for survivors at high risk of adverse effects from tobacco use and obesity.

CMS’s OCM is a five-year, episode-based payment model that encompasses more than 175 practices and includes an estimated 150 000 unique beneficiaries per year, more than 20% of Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries receiving chemotherapy for cancer (111). One of the requirements of the model is that physicians incorporate the 13 elements of the IOM cancer care plan (112) into their care for OCM beneficiaries. One of those elements is the provision of survivorship care planning for appropriate patients. This requirement, in a CMS model of this size, in conjunction with the CoC requirement, is having an important effect in making survivorship care planning an expected part of cancer care. This is especially true because many OCM practices provide these enhanced services to all of their patients, rather than making a distinction between Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries and other patients (R. Kline, personal communication).

Working Together to Make Electronic Health Records More Adaptable

Given the prevalence of electronic health records in modern medical practice, it is not surprising that much attention has focused on the challenges of integrating survivorship care plans into these records. The absence of structured mechanisms for incorporating survivorship care plans into electronic health records is one of the major challenges facing the widespread adoption of survivorship care plans for cancer patients. The CoC and OCM requirements are driving many electronic heath record vendors to incorporate templates for the documentation of survivorship care planning into their updated products to remain competitive. For example, the EPIC electronic health record has included survivorship care planning templates in a dropdown menu accessed through the problem list under the cancer diagnosis. The University of Pennsylvania Health System as well as a number of other health systems such as Kaiser Permanente have worked with EPIC to personalize and enhance these templates by auto-populating sections of the template with patient data that is within the EPIC chart (L. Jacobs, personal communication). Other solutions include efforts at individual practices to develop their own survivorship care planning templates, which can include surveillance testing schedules and information about the late effects of treatment. Once completed, these templates can then be shared with patients (R. Oyer, personal communication). These corporate and individual efforts, if broadly shared, can help electronic health records adapt to survivorship care planning needs.

Concluding Remarks

This workshop served as an important update to the 2006 IOM consensus study (3). The 12 years since that report have brought successes and challenges, with an acknowledgment that much work still needs to be done (Table 1). Reflecting on the presentations, the workshop co-leaders summarized the key themes that were discussed with specific recommendations to improve survivorship care in the next decade (Box 1). Although we have a greater knowledge about the ongoing challenges of cancer survivorship, the increased fragmentation of medical care delivery and its increasing costs have hampered effective and coordinated delivery of needed physical and psychosocial health services to long-term cancer survivors. This calls for an adequately educated and trained workforce knowledgeable about the physical, psychological, and socioeconomic needs of survivors and caregivers. This includes improved collection of outcomes data on survivors who have not been represented in extant research. Echoing recommendations of the 2013 IOM report on delivery of high-quality cancer care (112), there is an urgent need to integrate evidenced-based psychosocial services into standard medical care for cancer survivors from the time of diagnosis and in follow-up, including a focus on palliation of symptoms, prevention of late effects, and health promotion (62). New care delivery models will require the development and implementation of quality measures focused on survivorship care. There should be a greater focus on improved precision in cancer treatment, with the goal of delivery of appropriate and risk-adapted therapies to reduce the burden of chronic illness and second malignancies in survivors. Finally, recognition of the enormous financial burden of cancer care and its long-term impact on cancer survivors requires a focus on ensuring that follow-up care is accessible and affordable for all cancer survivors.

Box 1.

Recommendations to improve survivorship care

A healthcare workforce sufficiently educated and trained in the needs of cancer survivors, including changes in medical practice and education through existing accrediting organizations.

Increased focus on the physical, psychological, and socioeconomic needs of survivors and caregivers across the cancer care continuum, with the tools necessary to provide coordinated care.

Improved collection of outcomes data on diverse populations with cancer who have not been adequately represented in research studies on cancer survivors.

Better integration of evidence-based psychosocial services into the medical standard of care, and the elimination of services for which no evidence exists.

Development and implementation of quality measures for survivorship care (if you cannot measure it, you cannot evaluate it).

Risk assessment and intervention at diagnosis and follow-up so that clinicians can better understand how cancer treatment may affect a patient’s life as a survivor and tailor treatment accordingly.

Address the high risk for second malignant neoplasms in the survivor population by primary prevention, increased screening, and chemoprevention when available.

Improved precision in oncology (giving the right therapy to the right person at the right time), with the goal of delivering appropriate, risk-adapted, individualized therapies to reduce morbidity, minimize late effects, and optimize health care resources.

Delivery of high-quality survivorship healthcare focusing on palliation of symptoms, prevention of late effects, and health promotion.

Promotion of efforts to ensure that care is accessible and affordable for all cancer survivors.

Increasing awareness of the multiple challenges of cancer survivorship is only part of the effort to improve survivorship care. There is also a need to implement policy changes at government and nongovernmental levels, inspired by the increasing number of cancer survivors, and their awareness that their challenges are not unique. Potential policy levers include government action at the state and federal levels and an increased focus on survivorship issues in medical practice spurred by new educational requirements, accreditation standards, and the requirements of clinical practice.

Notes

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Baltimore, MD (RMK); Healthcare Delivery and Disparities Research Program, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Washington, DC (NKA); Department of Health Systems, Management, and Policy, School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver, CO (CJB); Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA (ERB, PAG); Office of Minority Health, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Baltimore, MD (DLG); Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (NBL); Independent Consultant in Survivorship and Medical Ethics, Arlington, VA (MSM); National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, Silver Spring, MD (SFN); Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (LN); Office of Cancer Survivorship, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (JHR); LIVESTRONG Cancer Institutes at Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX (RMS); Department of Health Policy & Management and Medicine, Schools of Public Health and Medicine, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA (RMS) (PAG).

Present affiliation: Smith Center for Healing and the Arts, Washington, DC (JHR).

The views, findings, and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or official policies of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (or its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee). We thank Sharyl Nass, Erin Balogh, Cyndi Trang, and Natalie Lubin, the staff of the National Cancer Policy Forum at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for their help in organizing and supporting this workshop.

References

- 1. Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Scribner’s; 2010:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2016-2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E.. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH.. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;257:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS.. Care patterns in medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;35611:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Financial Burden of Cancer Care. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/economic_burden. Accessed on June 1, 2018.

- 7. Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR.. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3130:3749–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK.. Going beyond lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;3518:1978–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA.. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(suppl 11):2577–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;664:271–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;346:611–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;644:225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;663:203–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN.. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;106:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;3217:1840–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;3218:1941–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Survivorship (Version 2.2017)2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 19. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care2016. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 20. Cleeland CS, Zhao F, Chang VT, et al. The symptom burden of cancer: evidence for a core set of cancer-related and treatment-related symptoms from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns study. Cancer. 2013;11924:4333–4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Esther Kim JE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, Jahan T, Miaskowski C.. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;374:715–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW.. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;1342:459–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, et al. Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;309:936–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun Y, Shigaki CL, Armer JM.. Return to work among breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;253:709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duijts SF, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, van Muijen P, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ.. Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;235:481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oeffinger KC, Baxi SS, Novetsky Friedman D, Moskowitz CS.. Solid tumor second primary neoplasms: who is at risk, what can we do? Semin Oncol. 2013;406:676–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morton LM, Onel K, Curtis RE, Hungate EA, Armstrong GT.. The rising incidence of second cancers: patterns of occurrence and identification of risk factors for children and adults. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014:e57–e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murphy CC, Gerber DE, Pruitt SL.. Prevalence of prior cancer among persons newly diagnosed with cancer: an initial report from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. JAMA Oncology. 2017; doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Stewart SL, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;611:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hudson MM. A model for care across the cancer continuum. Cancer. 2005;104(suppl 11):2638–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. Survivorship: healthy lifestyles, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;129:1222–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, Schumacher H, Rajkumar R, Conway PH.. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services: using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;112:114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;358:893–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Silver JK, Baima J.. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;928:715–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silver JK, Baima J, Mayer RS.. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: an essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;635:295–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greenlee H, Shi Z, Sardo Molmenti CL, Rundle A, Tsai WY.. Trends in obesity prevalence in adults with a history of cancer: results from the US National Health Interview Survey, 1997 to 2014. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3426:3133–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang FF, Liu S, John EM, Must A, Demark-Wahnefried W.. Diet quality of cancer survivors and non-cancer individuals: results from a national survey. Cancer. 2015;12123:4212–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T.. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;2334:8884–8893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Adler NE, Page AEK.. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3116:1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;148:721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: their nature, associations and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2002;2014:3137–3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brothers B, Yang HC, Strunk D, Andersen BL.. Cancer patients with major depressive disorder: testing a biobehavioral/cognitive behavioral intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;792:253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;244:653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. D'Agostino NM, Edelstein K, Zhang N, et al. Comorbid symptoms of emotional distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2016;12220:3215–3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weisman AD. Early diagnosis of vulnerability in cancer patients. Am J Med Sci. 1976;2712:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinical guidance for responding to suffering in adults with cancer. Cancer Australia 2014. http://guidelines.canceraustralia.gov.au/guidelines/guideline_22.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Batty GD, Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Kivimaki M.. Psychological distress in relation to cancer specific mortality: Pooling of unpublished data from 16 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;356:j108. 25; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Antoni MH.. Host factors and cancer progression: Biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. J Clin Oncol. 2010;2826:4094–4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coughfrey A, Millington A, Bennett S, et al. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for psychological outcomes in paediatric oncology: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;17:30523–30527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stanton A, Rowland JH, Ganz PA.. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: contributions from psychosocial oncology research. Am Psychol. 2015;702:159–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R.. Effects of psychosocial interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;316:782–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lutgendorf SK, Andersen BL.. Biobehavioral approaches to cancer progression and survival: mechanisms and interventions. Am Psychol. 2015;702:186–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Romito F, Goldzweig G, Cormio C, Hagedoorn M, Andersen BL.. Informal caregiving for cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119(Suppl 11):2160–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;201:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.: An Intense, Episodic and Challenging Care Experience. Report prepared by the National Alliance for Caregiving, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Support Community, June 2016. http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2018.

- 57. de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al. Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;111:48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Alfano CM, NcNeel TS.. Parental cancer and the family: a population based estimate of the number of US cancer survivors residing with their minor children. Cancer. 2010;11618:4395–4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Litzelman KI, Green PA, Yabroff KR.. Cancer and quality of life in spousal dyads: spillover in couples with and without cancer-related health problems. Support Care Cancer. 2016;242:763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Frambes D, Given B, Lehto R, Sikorskii A, Wyatt G.. Informal caregivers of cancer patients: review of interventions, care activities, and outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2018;407:1069–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. NCCN guideline insights: survivors, version 1: 2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;146:715–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;3215:1605–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;12213:1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Alfano CA, Smith T, de Moor JS, et al. An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;10611:dju287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Andersen BL, Dorfman CS.. Evidence-based psychosocial treatment in the community: considerations for dissemination and implementation. Psychooncology. 2016;255:482–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Andersen BO, Goyal NG, Westbrook TD, Bishop B, Carson WE 3rd.. Trajectories of stress, depressive symptoms, and immunity in cancer survivors: diagnosis to 5 years. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;231:52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Forsythe LP, Alfano CA, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH.. Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012;3023:2897–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CDE, Cohn RJ.. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;3110:1222–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. (P.L. 111-148), as amended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-152), together referred to as the Affordable Care Act.

- 70. Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S.. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;514:213–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A.. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;224:745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, Chubak J.. Cancer survivors' experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: Results from a multisite study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;106:1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McDermott C. Financial toxicity: a common but rarely discussed treatment side effect. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;1412:1750–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM.. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;11614:3493–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;11920:3710–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lu CY, Zhang F, Wagner AK, et al. Impact of high-deductible insurance on adjuvant hormonal therapy use in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018; doi:10.1007/s10549-018-4821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lee MJ, Khan MM, Salloum RG.. Recent Trends in cost-related medication nonadherence among cancer survivors in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;241:56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Jagsi R, Katz S, Hawley S.. Prescription drug coverage: implications for hormonal therapy adherence in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;1542:417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Guy GP Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Healthcare expenditure burden among non-elderly cancer survivors, 2008-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6 suppl 5):S489–S497. 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR.. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;1092:djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Head B, Harris L, Kayser K, Martin A, Smith LA.. If the disease was not enough: coping with the financial consequences of cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;263:975–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shih YT, Chien CR.. A review of cost communication in oncology: patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcomes assessment. Cancer. 2017;1236:928–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS.. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;682:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Neumark D, Bradley CJ, Henry M, Dahman B.. Work continuation while treated for breast cancer: the role of workplace accommodations. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2015;684:916–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. http://sbecouncil.org/about-us/facts-and-data/, Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 86. Surbone A, Tralongo P.. Categorization of cancer survivors: why we need it. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3428:3372–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sussman J, Mcbride ML, Sisler J, et al. Integrating primary care and cancer care in survivorship: a collaborative approach. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl/3s):abstract 103. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sussman J, Souter LH, Grunfeld E, et al. Models of Care for Cancer Survivorship. Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Oct 26 Program in Evidence-Based Care. Evidence-Based Series No.: 26–21. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;64:359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Viswanathan M, Halpern M, Swinson Evans T, Birken SA, Mayer DK, Basch E. Models of cancer survivorship care. Technical Brief. No. 14 (Prepared for the RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under contract No. 290-2012-00008-1-I) AHRQ Publication No. 14 -EHC011-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed]

- 91. Towle EL, Barr TR, Hanley A, et al. Results of the ASCO study of collaborative practice arrangements. J Oncol Pract. 2011;75:278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jefford M, Emery J, Grunfeld E, et al. SCORE: shared care of colorectal cancer survivors: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;181:506.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Verschuur EML, Steyerberg EW, Tilanus HW, et al. Nurse-led follow-up after oesphageal or gastri cardia cancer surgery: a randomized trial. Br J Cancer. 2009;1001:70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Medicine I. O. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. https://survivorsym.org. Accessed November 11, 2017.

- 96. McCabe MS, Jacobs LA.. Clinical update: survivorship care-models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;283:e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS.. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;2432:5117–5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, Hudson MM.. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;406:804–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Nekhlyudov L, O'malley DM, Hudson SV.. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:e30–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J.. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;482:177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Trotter K, Frazier Trotter K, Frazier A, Hendricks CK, Scarsella H.. Innovation in survivor care: group visits. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;152:e24–e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/index.do. Accessed on May 16, 2018.

- 103. Oeffinger KC, Argenbright KE, Levitt GA, et al. Models of cancer survivorship health care: moving forward. Am Soc Clin Oncol Edu Book. 2014:205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc. Accessed on February 18, 2018.

- 105. https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/index.html. Accessed on May 27, 2018.

- 106. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/USCS/DataViz.html. Accessed on May 27, 2018.

- 107. https://www.naaccr.org/interactive-data-on-line/. Accessed on May 27, 2018.

- 108. http://oliver.facs.org/BMPub/. Accessed on May 27, 2018.

- 109. https://www.cibmtr.org/Meetings/Materials/CSOAForum/Documents/2016%20Center%20Outcomes%20Forum%20Summary%20FINAL%202017-03-24.pdf. Accessed on February 18, 2018.

- 110. https://bloodcell.transplant.hrsa.gov/research/transplant_data/us_tx_data/survival_data/survival.aspx. Accessed on February 18, 2018.

- 111. Kline RM, Adelson K, Kirshner JJ, et al. The oncology care model: perspectives from the centers for medicare & medicaid services and participating oncology practices in academia and the community. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book.2017:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, Ganz PA.. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]