Summary

Beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate (HMB) is a leucine metabolite with protein anabolic effects. We examined the effects of an HMB‐enriched diet in healthy rats and rats with liver cirrhosis induced by multiple doses of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). HMB increased branched‐chain amino acids (BCAAs; valine, leucine and isoleucine) in blood and BCAA and ATP in muscles of healthy animals. The effect on muscle mass and protein content was insignificant. In CCl4‐treated animals alterations characteristic of liver cirrhosis were found with decreased ratio of the BCAA to aromatic amino acids in blood and lower muscle mass and ATP content when compared with controls. In CCl4‐treated animals consuming HMB, we observed higher mortality, lower body weight, higher BCAA levels in blood plasma, higher ATP content in muscles, and lower ATP content and higher cathepsin B and L activities in the liver when compared with CCl4‐treated animals without HMB. We conclude that (1) HMB supplementation has a positive effect on muscle mitochondrial function and enhances BCAA concentrations in healthy animals and (2) the effects of HMB on the course of liver cirrhosis in CCl4‐treated rats are detrimental. Further studies examining the effects of HMB in other models of hepatic injury are needed to determine pros and cons of HMB in the treatment of subjects with liver cirrhosis.

Keywords: branched‐chain amino acids, hepatic cachexia, insulin resistance, leucine, liver cirrhosis

1. INTRODUCTION

Beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate (HMB) is a leucine metabolite with protein anabolic effects, which might be effective in the treatment of muscle wasting disorders. HMB has been shown to stimulate protein synthesis through the mTOR system, increase expression of pituitary growth hormone mRNA and IGF‐1 levels, decrease proteasome enzyme activities, reduce the apoptosis of myonuclei, increase mitochondrial biogenesis and fat oxidation, and improve excitation‐contraction coupling in muscles.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In humans, positive effects of HMB were observed in the elderly, and those with sepsis, chronic cardiac and pulmonary disease, hip fracture, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and AIDS‐ and cancer‐related cachexia.6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Severe loss of skeletal muscle is frequently found in patients with liver cirrhosis and results in decreased survival, lower quality of life and higher frequency of complications of cirrhosis.11 However, surprisingly, there are no reports regarding the effects of HMB supplementation although positive effects of HMB on muscle mass and muscle performance, which have been reported in several articles,1, 3, 4, 10 could improve the clinical outcomes of cirrhotic subjects.

We found that HMB decreased proteolysis in muscles of partially hepatectomized animals and increased DNA content and DNA fragmentation in the remnant of regenerating liver.12 These findings indicate that HMB may affect not only muscle protein balance, but also the repair of injured liver. In addition, several studies demonstrated that HMB increases plasma concentrations of branched‐chain amino acids (BCAAs; valine, leucine and isoleucine).12, 13 The BCAAs are constantly decreased in cirrhotic subjects, and it is consensus that decreased BCAA levels, together with increased levels of aromatic amino acids (AAAs; phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan), play a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy.14, 15, 16 In summary, there are a number of findings that indicate the rationality of using HMB as a supplement for patients with liver cirrhosis.

In our recent study, we demonstrated that rats treated chronically by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) exhibit muscle loss and multiple similarities with liver cirrhosis in humans.17 The main aim of the present study was to examine the effects of HMB supplementation on muscle protein balance and amino acid concentrations in rats with advanced form of liver cirrhosis. Because there are different sensitivities of slow‐ and fast‐twitch muscles to various signals,18, 19 muscles of different metabolic properties [ie, musculus soleus (SOL, slow‐twitch, red muscle), musculus extensor digitorum longus (EDL, fast‐twitch, white muscle) and musculus tibialis anterior (TIB, composed mostly of white fibres)] were examined.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and materials

Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were housed in standard cages in quarters with controlled temperature and a 12‐hour light‐dark cycle. The rats were maintained on an ST‐1 (Velas, CR) standard laboratory diet containing (w/w) 24% nitrogen compounds, 4% fat, 70% carbohydrates and 2% minerals and vitamins, and were provided drinking water ad libitum. HMB (calcium salt) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical, Lachema, Waters, Biomol and Merck.

2.2. Ethical approval

The Animal Care and Use Committee of Charles University, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove (licence no. 144879/2011‐MZE‐17214) specifically approved this study on 1 November 2016 (identification code MSMT‐33747/2016‐4). All experimental procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

2.3. Experimental model and diets

Liver cirrhosis was induced by CCl4 (diluted 1:1 in the olive oil) administered orally by gavage at a dosage of 2 mL/kg of initial body weight, three times a week, for 7 weeks. Using this model, micronodular cirrhosis develops, reproducing most of the features of cirrhosis in humans including hyperammonaemia, portal‐systemic shunts, ascites and low BCAA‐to‐AAA plasma ratio.16, 17, 20 The control animals underwent vehicle administration only. An HMB‐enriched diet was prepared by mixing the standard laboratory diet with HMB in a ratio of 99:1. The dose of HMB was based on the results of our previous studies.12, 13

2.4. Experimental design

At the beginning of the study, a total of 48 male Wistar rats weighing approximately 220 g each were randomly divided into four groups, each containing 10 or 14 animals: (1) healthy controls fed a standard diet (Control, n = 10); (2) healthy controls fed an HMB‐enriched diet (HMB, n = 10); (3) animals treated with CCl4 and fed a standard diet (CCl4, n = 14); and (4) animals treated with CCl4 and fed an HMB‐enriched diet (CCl4 + HMB, n = 14). Consumption of food and body weight was measured three times a week. Food intake of a group of five rats was recalculated on a food intake of one animal and expressed in g/kg b.w./day.

At the end of the study, the overnight fasted animals were euthanized by exsanguination from the abdominal aorta after receiving ether anaesthesia. The liver, TIB, SOL and EDL were quickly removed and weighed. Small pieces (~ 0.1 g) of the tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Blood was collected in heparinized tubes and immediately centrifuged for 15 minutes at 2200 × g using a refrigerated centrifuge; blood plasma was transferred into clean polypropylene tubes using a Pasteur pipette.

2.5. Amino acid concentrations in blood plasma and tissues

Amino acid concentrations were determined in the supernatants of deproteinized samples of blood plasma and tissues using high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Alliance 2695, Waters) after derivatization with 6‐aminoquinolyl‐N‐hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate. The results were expressed in μmol/L of blood plasma or nmol/g of wet tissue.

2.6. Chymotrypsin‐like activity (CHTLA) of proteasome and cathepsin B and L activities

The CHTLA of the proteasome and cathepsin B and L activities were determined using the fluorogenic substrates Suc‐LLVY‐MCA and Z‐FA‐MCA, respectively, as previously described in detail.21, 22, 23 The fluorescence of the samples was measured at the excitation wavelength of 340 nm and the emission wavelength of 440 nm (Tecan Infinite M200). A standard curve was established for 7‐amino‐4‐methylcoumarin (AMC), which allowed expression of the enzyme activities in nmol of AMC/g protein/hour.

2.7. Adenine nucleotides

The reversed‐phase HPLC (Alliance 2695, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) combined with UV detection was used for the determination of ATP, ADP and AMP concentrations. The HPLC conditions were as follows: LiChroCART 250 × 4 mm, Purospher Star RP‐18 (5 μm) endcapped analytical column (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt Germany) using the mobile phase consisting of methanol and buffer (50 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH = 6) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min in a gradient mode. Peaks were detected at 254 nm and quantified by the external standard method. The results are expressed as μmol/L of blood plasma or μmol/g of wet tissue.

2.8. Other techniques

Plasma levels of ammonia, urea, bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma‐glutamyltransferase (GMT) were measured using commercial tests (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany; Elitech, Sées, France and Lachema, Brno, CR). Ammonia concentration was measured using glutamate‐dehydrogenase assay in deproteinized samples of blood plasma to avoid the influence of high levels of hepatic enzymes on NADH consumption.24

2.9. Statistical analyses

The results of statistical analyses are expressed as means ± standard errors (SEs). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc analysis was used to detect differences between multiple independent groups. NCSS 2001 statistical software was used for analyses. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Food intake, body weights and mortality

At the initial phase of the study, the intake of food was lower in CCl4‐treated animals and in animals fed by the HMB‐enriched diet than in controls. The differences in daily food intake (g/kg b.w./day) disappeared on the 4th day. There was a significantly lower increase in body weight in CCl4‐treated animals than in controls. The gain of body weight in the CCl4 + HMB group was significantly lower when compared with the CCl4 group without HMB (Table 1). One animal of the CCl4 group and four animals of the CCl4 + HMB group died during the last week of the study.

Table 1.

Effects of HMB and CCl4 on body weight and food intake

| Control (n = 10) | HMB (n = 10) | CCL4 (n = 13) | CCL4 + HMB (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food intake (g/kg b. w./day) | ||||

| Day 2 | 129 ± 2 | 99 ± 1b | 91 ± 1 a | 70 ± 1a , b |

| Day 4 | 111 ± 2 | 106 ± 2 | 107 ± 1 | 102 ± 1 |

| Day 10 | 94 ± 1 | 91 ± 2 | 89 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 |

| Day 20 | 86 ± 2 | 82 ± 1 | 94 ± 2 a | 86 ± 2 |

| Day 42 | 77 ± 2 | 74 ± 1 | 73 ± 1 | 69 ± 2 |

| Body weight (g) | ||||

| Initial | 221 ± 2 | 219 ± 3 | 221 ± 2 | 217 ± 1 |

| Day 4 | 265 ± 3 | 260 ± 3 | 245 ± 3 a | 226 ± 3a , b |

| Day 10 | 328 ± 5 | 319 ± 5 | 281 ± 4 a | 277 ± 3 a |

| Day 20 | 381 ± 7 | 370 ± 6 | 338 ± 6 a | 320 ± 3 a |

| Final | 495 ± 12 | 455 ± 8 | 420 ± 13 a | 367 ± 9 a |

| Gain (final‐initial) | 274 ± 11 | 237 ± 7 | 199 ± 13 a | 146 ± 10a , b |

Means ± SE, P ˂ 0.05.

Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB).

Effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4).

3.2. Alterations in blood biochemical markers

In the HMB group, we found significantly lower concentrations of glucose than in the control group (Table 2). Concentrations of glucose and albumin decreased, whereas concentrations of bilirubin, ALT, AST, ALP, GMT and ammonia increased in the blood plasma of CCl4‐treated animals. The differences between CCl4‐treated animals fed by the HMB‐enriched diet and CCl4‐treated animals without HMB were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Effects of HMB and CCl4 on blood biochemical markers

| CONTROL (n = 10) | HMB (n = 10) | CCl4 (n = 13) | CCL4 + HMB (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 8.71 ± 0.38 | 7.41 ± 0.27b | 4.69 ± 0.27 a | 4.38 ± 0.22 a |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.1 ± 0.3 | 43.0 ± 0.4 | 27.4 ± 1.9a | 24.5 ± 2.4 a |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 6.90 ± 0.37 | 5.64 ± 0.14 | 5.60 ± 0.73 | 6.27 ± 0.92 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 24.8 ± 6.7 a | 17.8 ± 3.3 a |

| ALT (μkat/L) | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 6.58 ± 0.99 a | 4.83 ± 0.77a |

| AST (μkat/L) | 1.27 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.09 | 14.28 ± 2.16a | 12.77 ± 2.43a |

| ALP (μkat/L) | 1.34 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 5.66 ± 0.70 a | 5.53 ± 0.50 a |

| GMT (μkat/L) | ND | ND | 0.15 ± 0.03 a | 0.12 ± 0.02 a |

| Ammonia (μmol/L) | 31 ± 3 | 29 ± 3 | 111 ± 12 a | 110 ± 11 a |

Means ± SE, P ˂ 0.05.

Abbreviation: ND, not detectable.

Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB).

Effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4).

3.3. Amino acids in blood plasma

Significantly higher concentrations of all three BCAA were found in the blood plasma of animals consuming HMB than those in controls (Table 3). In cirrhotic animals increased concentrations of histidine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, glutamine, citrulline and ornithine were found, whereas the BCAAs, alanine, glutamate, aspartate, glycine, serine and taurine decreased. In CCl4‐treated animals consuming HMB, we observed higher BCAA levels when compared with CCl4‐treated animals on a diet without HMB. The BCAA‐to‐AAA ratio was significantly lower in both CCl4‐treated groups and remained unaffected by HMB.

Table 3.

Effects of HMB and CCl4 on amino acid concentrations in blood plasma

| PLASMA | Control (n = 10) | HMB (n = 10) | CCL4 (n = 13) | CCL4 + HMB (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential amino acids (EAAs) | ||||

| Histidine | 53 ± 1 | 56 ± 2 | 83 ± 4 a | 81 ± 4 a |

| Isoleucine | 102 ± 4 | 128 ± 5b | 52 ± 3 a | 70 ± 3a , b |

| Leucine | 149 ± 6 | 185 ± 8b | 74 ± 3 a | 92 ± 5 a , b |

| Lysine | 384 ± 9 | 434 ± 17 | 399 ± 23 | 394 ± 23 |

| Methionine | 54 ± 1 | 61 ± 2 | 49 ± 3 | 54 ± 3 |

| Phenylalanine | 71 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 100 ± 5 a | 103 ± 4 a |

| Threonine | 265 ± 12 | 295 ± 6 | 179 ± 13 a | 183 ± 14 a |

| Valine | 190 ± 6 | 229 ± 8 b | 104 ± 4 a | 128 ± 5 a , b |

| Σ BCAA | 441 ± 15 | 543 ± 21 b | 245 ± 18 a | 290 ± 13 a , b |

| Σ EAA | 1267 ± 25 | 1462 ± 33b | 1040 ± 48 a | 1104 ± 48 a |

| Non‐essential amino acids (NEAAs) | ||||

| Alanine | 372 ± 14 | 367 ± 22 | 206 ± 17 a | 224 ± 12 a |

| Arginine | 153 ± 5 | 161 ± 7 | 144 ± 7 | 157 ± 7 |

| Asparagine | 58 ± 2 | 60 ± 2 | 56 ± 3 | 61 ± 3 |

| Aspartate | 19 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 a | 8 ± 1 a |

| Citrulline | 79 ± 1 | 79 ± 2 | 145 ± 11 a | 137 ± 12 a |

| Glutamate | 124 ± 5 | 114 ± 5 | 51 ± 8 a | 41 ± 3 a |

| Glutamine | 561 ± 13 | 570 ± 13 | 764 ± 26 a | 717 ± 34 a |

| Glycine | 379 ± 23 | 391 ± 10 | 221 ± 12 a | 227 ± 17 a |

| Ornithine | 59 ± 3 | 68 ± 3 | 127 ± 4 a | 119 ± 6 a |

| Proline | 131 ± 4 | 144 ± 3 | 135 ± 8 | 140 ± 8 |

| Serine | 228 ± 8 | 253 ± 3 | 193 ± 19 | 190 ± 23 a |

| Taurine | 295 ± 22 | 289 ± 18 | 191 ± 13 a | 217 ± 15 a |

| Tyrosine | 91 ± 2 | 103 ± 4 | 156 ± 11 a | 160 ± 8 a |

| Σ NEAA | 2,681 ± 47 | 2,732 ± 36 | 2,496 ± 91 | 2,480 ± 95 |

| Σ Amino acids | 3,949 ± 66 | 4,194 ± 59 | 3,536 ± 132 a | 3,584 ± 138 a |

| BCAAs/AAAs | 2.72 ± 0.08 | 3.07 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.06 a | 1.12 ± 0.07 a |

The values are in μmol/L of plasma. Means ± SE, P ˂ 0.05.

Abbreviations: AAAs, aromatic amino acids; BCAAs, branched‐chain amino acids.

Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB).

Effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4).

3.4. Branched‐chain amino acids in the liver and muscles

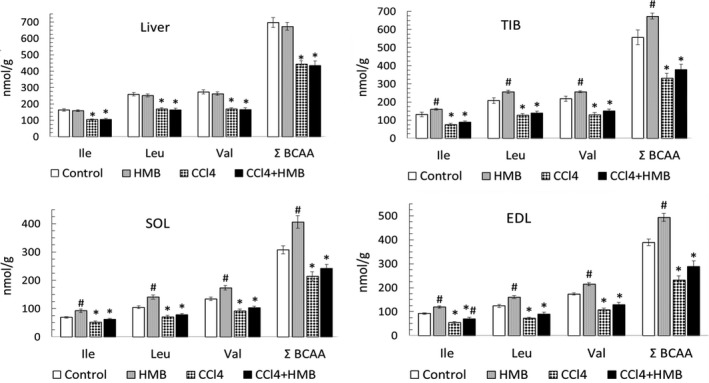

HMB supplementation increased the BCAA concentration in the muscles of healthy animals (Figure 1). The effect of HMB on BCAA concentration in the liver and on tissue concentrations of other amino acids was mostly not significant. In animals with liver cirrhosis, we found decreased concentrations of BCAA in the liver and muscles. The levels were significantly lower in TIB and EDL (decreased by 40%) than in SOL (decreased by 30%). The effect of HMB on BCAA concentration in tissues of cirrhotic animals was, except the higher isoleucine (Ile) concentration in EDL, statistically not significant.

Figure 1.

Effects of HMB on branched‐chain amino acid (BCAA) concentrations in the liver and various types of skeletal muscle of healthy and CCl4‐treated rats. Means ± SE, ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparisons, P ˂ 0.05. * Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB); # effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4)

3.5. Alterations in weight and protein content of liver and muscles

We did not find an effect of the HMB‐enriched diet on weight and protein content of the liver and muscles in healthy animals (Table 4). Muscle mass and muscle protein content were significantly lower in CCl4‐treated animals when compared with controls. The differences between CCl4‐treated animals fed by the HMB‐enriched diet and on a diet without HMB were statistically not significant, except for lower weight and protein content in the liver and TIB in the CCl4 + HMB group.

Table 4.

Effects of HMB and CCl4 on weight and protein content of tissues

| Control (n = 10) | HMB (n = 10) | CCL4 (n = 13) | CCL4 + HMB (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIVER | ||||

| Weight ‐ g | 13.3 ± 0.4 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 14.0 ± 1.3 | 10.3 ± 0.9 b |

| g/kg b.w. | 26.9 ± 0.3 | 26.9 ± 0.6 | 31.5 ± 2.1 | 28.0 ± 2.3 |

| Protein ‐ mg/g | 217 ± 2 | 214 ± 4 | 162 ± 4 a | 171 ± 5a |

| g | 2.88 ± 0.08 | 2.61 ± 0.05 | 2.15 ± 0.18 a | 1.74 ± 0.14 a |

| g/kg b.w. | 5.82 ± 0.06 | 5.71 ± 0.11 | 5.39 ± 0.45 | 4.73 ± 0.33 b |

| SOL | ||||

| Weight ‐ g | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.00 a |

| g/kg b.w. | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.01 a |

| Protein ‐ mg/g | 180 ± 9 | 178 ± 8 | 176 ± 4 | 170 ± 7 |

| g | 41.9 ± 2.0 | 41.7 ± 2.1 | 31.7 ± 1.2a | 28.7 ± 1.1a |

| g/kg b.w. | 85.3 ± 5.1 | 91.6 ± 4.6 | 75.6 ± 2.3 | 78.2 ± 1.9 |

| EDL | ||||

| Weight ‐ g | 0.21 ± 0.00 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.15 ± 0.00 a |

| g/kg b.w. | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.01a |

| Protein ‐ mg/g | 164 ± 4 | 176 ± 4 | 173 ± 6 | 178 ± 5 |

| g | 34.4 ± 1.4 | 35.7 ± 0.7 | 28.3 ± 1.3 a | 26.7 ± 1.3 a |

| g/kg b.w. | 69.9 ± 3.2 | 78.7 ± 2.3 | 67.4 ± 2.8 | 72.9 ± 3.3 |

| TIB | ||||

| Weight ‐ g | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.03a | 0.59 ± 0.02a , b |

| g/kg b.w. | 1.71 ± 0.05 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 1.61 ± 0.04 | 1.62 ± 0.06 a |

| Protein ‐ mg/g | 174 ± 3 | 163 ± 9 | 159 ± 5 | 145 ± 6 |

| g | 146 ± 5 | 134 ± 5 | 107 ± 5a | 86 ± 5 a , b |

| g/kg b.w. | 297 ± 10 | 294 ± 11 | 255 ± 9 a | 236 ± 13 a |

Means ± SE, P ˂ 0.05.

Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB).

Effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4).

3.6. Alterations in protein breakdown

The effect of HMB on CHTLA and cathepsin B and L activities in healthy animals was statistically not significant (Table 5). Chronic administration of CCl4 enhanced CHTLA and cathepsin B and L activities in the liver and CHTLA in TIB. Cathepsins B and L activities in the liver of CCl4‐treated animals were significantly higher in animals fed by an HMB‐enriched diet.

Table 5.

Effects of HMB and CCl4 on proteolysis

| Control (n = 10) | HMB (n = 10) | CCL4 (n = 13) | CCL4 + HMB (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIVER | ||||

| Cathepsins B and L | 422 ± 19 | 323 ± 27 | 584 ± 35 a | 695 ± 38 a , b |

| CHTLA | 3.23 ± 0.12 | 2.75 ± 0.09 | 4.71 ± 0.14 a | 4.52 ± 0.36a |

| TIB | ||||

| Cathepsins B and L | 7.05 ± 1.43 | 5.84 ± 1.09 | 7.01 ± 1.04 | 8.08 ± 1.74 |

| CHTLA | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 1.26 ± 0.07 | 2.07 ± 0.11 a | 2.15 ± 0.18 a |

The values are in nmol AMC/mg/hour. Means ± SE, P ˂ 0.05.

Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB).

Effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4).

3.7. Alterations in adenine nucleotides

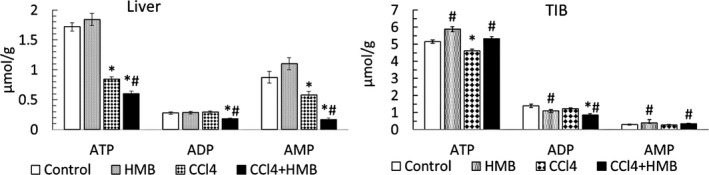

The HMB‐enriched diet had no statistically significant effect on adenine nucleotide concentrations in the liver (Figure 2). However, in TIB, HMB supplementation increased ATP and AMP, and decreased ADP levels. In CCl4‐treated animals, we observed decreased ATP concentration in both the liver and the TIB. The ATP decrease in the liver was more pronounced in HMB‐supplemented animals. However, ATP concentration in TIB was higher in the CCl4 + HMB group than in the CCl4 group.

Figure 2.

Effects of HMB on adenine nucleotide concentrations in the liver and tibialis muscle (TIB) in healthy and CCl4‐treated rats. Means ± SE, ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparisons, P ˂ 0.05. * Effect of CCl4 (CCL4 vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs HMB); # effect of HMB (HMB vs Control or CCL4 + HMB vs CCL4)

4. DISCUSSION

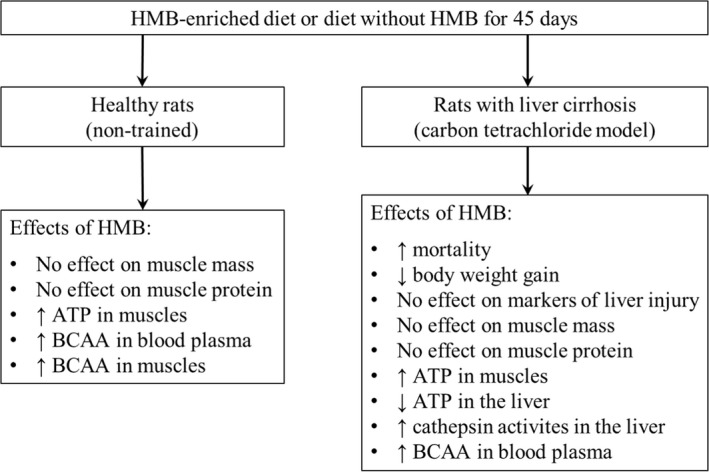

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effects of chronic consumption of an HMB‐enriched diet on muscle protein balance and BCAA levels in subjects with liver cirrhosis. The findings in our summary show that whereas some benefits of HMB consumption can be observed in healthy subjects, the effects in CCl4‐treated animals are rather harmful (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Summary of observed effects of HMB supplementation in healthy and CCl4‐treated rats

4.1. Effects of HMB in healthy animals

We did not observe a significant influence of HMB on muscle mass and protein content in healthy animals. The finding is in agreement with several studies suggesting that anabolic effects of HMB supplementation on skeletal muscle do not occur in healthy, non‐exercising subjects.3, 25 Nevertheless, increased ATP content in TIB indicates positive effect of HMB on mitochondrial function in muscles.

A potentially important effect of an HMB‐enriched diet is an increase in concentration of the BCAA in blood plasma and muscles. A similar finding was reported after a short‐term infusion of HMB to healthy and partially hepatectomized animals.12, 13 The mechanism responsible for the increase in BCAA is unclear. Oxidation of all three BCAAs is regulated by branched‐chain keto acid dehydrogenase, which is sensitive to many influences, including nutrients and metabolites. It can be hypothesized that HMB or its metabolites affect the activity state of the enzyme. Using labelled leucine, it was demonstrated that HMB decreased the rate of leucine oxidation by isolated muscles obtained from endotoxin‐treated rats.3

4.2. Alterations induced by CCL4

Remarkable increase in ammonia and bilirubin, decrease in albumin in blood plasma, and a marked decrease in hepatic ATP indicate the presence of advanced form of liver cirrhosis. In addition to changes of the main markers of chronic hepatic injury, significant abnormalities were found in amino acid concentrations. The decrease in the ratio of BCAA to AAA is characteristic for liver cirrhosis and plays a role in the development of hepatic encephalopathy.14 An increased concentration of glutamine and decreased levels of BCAA, glutamate and aspartate are caused by enhanced ammonia detoxification to glutamine in muscles.17, 26, 27

Increased CHTLA in TIB and CHTLA and cathepsin B and L activities in the liver point to enhanced proteolysis in the liver and muscles. More pronounced decreases in the BCAA concentration in EDL and TIB than in SOL confirm the previous observations of differences in the response of white and red muscles to various signals.18, 19 Nevertheless, the degrees of the loss of weight and protein content of muscles examined in the present study were similar.

Lower glycaemia in overnight starving animals with liver cirrhosis is due to reduced stores of hepatic glycogen. Therefore, merely an overnight fast may activate catabolic reactions in subjects with cirrhosis. The explanation is supported by a decreased plasma concentration of alanine, the main gluconeogenic amino acid, which is synthesized in the early stage of starvation in muscles.

4.3. Effects of HMB in CCl4‐treated animals

Higher mortality, lower body weight gain, lower protein content in TIB and lower ATP content in the liver of CCl4‐treated animals consuming HMB when compared with CCl4‐treated controls indicate adverse effects of HMB on the course of liver cirrhosis. The positive effects of HMB supplementation can be considered only in a higher concentration of BCAA in blood plasma and ATP content in the TIB.

The explanation of the surprisingly unfavourable effects of HMB supplementation in CCl4‐treated animals is unclear. The more pronounced decrease in hepatic ATP content when compared with CCl4‐treated animals without HMB may play a role in this. The studies indicate that mitochondrial energy production in hepatocytes remains intact during the early stages of chronic liver injury and that the failure to maintain adequate amounts of ATP is associated with progression of liver disease and death.28

In this context, it should be noted that impaired insulin sensitivity has been demonstrated in healthy sedentary rats supplemented with HMB for 4 weeks and that increased levels of the BCAA in blood plasma are a typical finding in insulin‐resistant states, such as short‐term starvation, obesity and diabetes.29, 30 An increased BCAA level in muscles has been found in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat.31 Therefore, it might be suggested that the adverse effects of HMB on the course of liver disease and an increase in the BCAA in blood plasma and muscles are related to impaired sensitivity to insulin.

A likely mechanism of BCAA increase in blood plasma in insulin‐resistant states is the activation of proteolysis in the liver. Since the aminotransferase for the BCAA is absent in the liver, the BCAAs are, unlike other amino acids that are catabolized, released into the bloodstream.29 The speculation is supported by the observation of higher cathepsin B and L activities in the liver of CCl4‐treated animals consuming HMB. As the BCAA decrease in blood plasma plays a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy, the effect of HMB on plasma BCAA concentration might be of interest.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that (1) HMB supplementation does not affect the mass and protein content of muscles but increases muscle ATP content and BCAA concentrations in blood plasma and muscles of healthy rats; and (2) the effects of HMB supplementation on the course of liver cirrhosis in CCl4‐treated rats are detrimental (Figure 3). Further studies examining the effects of HMB in other models of hepatic injury are needed to determine pros and cons of HMB in the treatment of liver cirrhosis. We hope that our study, which indicates not only the negative but also some positive effects of HMB, will stimulate systematic investigation that will allow the ultimate verdict of the HMB's suitability in patients with liver cirrhosis.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.H. outlined the experiments, performed statistical analysis and data interpretation, and prepared the manuscript. M.W. was involved in data acquisition and the writing of the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank R. Fingrova, K. Sildbergerova and D. Jezkova for their technical assistance.

Holeček M, Vodeničarovová M. Effects of beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate supplementation on skeletal muscle in healthy and cirrhotic rats. Int. J. Exp. Path. 2019;100:175‐183. 10.1111/iep.12322

Funding information

This work was supported by the programme PROGRES Q40/02

REFERENCES

- 1. Pinheiro CH, Gerlinger‐Romero F, Guimarães‐Ferreira L, et al. Metabolic and functional effects of beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate (HMB) supplementation in skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:2531‐2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. He X, Duan Y, Yao K, et al. β‐Hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate, mitochondrial biogenesis, and skeletal muscle health. Amino Acids. 2016;48:653‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kovarik M, Muthny T, Sispera L, et al. Effects of β‐hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate treatment in different types of skeletal muscle of intact and septic rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2010;66:311‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Girón MD, Vílchez JD, Salto R, et al. Conversion of leucine to β‐hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate by α‐keto isocaproate dioxygenase is required for a potent stimulation of protein synthesis in L6 rat myotubes. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:68‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vallejo J, Spence M, Cheng AL, et al. Cellular and physiological effects of dietary supplementation with β‐hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate (HMB) and β‐alanine in late middle‐aged mice. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark RH, Feleke G, Din M, et al. Nutritional treatment for acquired immunodeficiency virus‐associated wasting using beta‐hydroxy beta‐methylbutyrate, glutamine, and arginine: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2000;24:133‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ekinci O, Yanık S, Terzioğlu Bebitoğlu B, et al. Effect of calcium β‐hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate (CaHMB), vitamin D, and protein supplementation on postoperative immobilization in malnourished older adult patients with hip fracture: a randomized controlled study. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31:829‐835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olveira G, Olveira C, Doña E, et al. Oral supplement enriched in HMB combined with pulmonary rehabilitation improves body composition and health related quality of life in patients with bronchiectasis (Prospective, Randomised Study). Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1015‐2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rathmacher JA, Nissen S, Panton L, et al. Supplementation with a combination of beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate (HMB), arginine, and glutamine is safe and could improve hematological parameters. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:65‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holeček M. Beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate supplementation and skeletal muscle in healthy and muscle‐wasting conditions. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:529‐541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dasarathy S, Hatzoglou M. Hyperammonemia and proteostasis in cirrhosis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:30‐36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holeček M, Vodeničarovová M. Effects of beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate in partially hepatectomized rats. Physiol Res. 2018;67:741‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holecek M, Muthny T, Kovarik M, et al. Effect of beta‐hydroxy‐beta‐methylbutyrate (HMB) on protein metabolism in whole body and in selected tissues. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:255‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer JE, Funovics JM, Aguirre A, et al. The role of plasma amino acids in hepatic encephalopathy. Surgery. 1975;78:276‐290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holecek M. Three targets of branched‐chain amino acid supplementation in the treatment of liver disease. Nutrition. 2010;26:482‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holeček M, Mráz J, Tilšer I. Plasma amino acids in four models of experimental liver injury in rats. Amino Acids. 1996;10:229‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holeček M, Vodeničarovová M. Muscle wasting and branched‐chain amino acid, alpha‐ketoglutarate, and ATP depletion in a rat model of liver cirrhosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2018;99:274‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kadlcikova J, Holecek M, Safranek R, et al. Effects of proteasome inhibitors MG132, ZL3VS and AdaAhx3L3VS on protein metabolism in septic rats. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:365‐371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holeček M, Mičuda S. Amino acid concentrations and protein metabolism of two types of rat skeletal muscle in postprandial state and after brief starvation. Physiol Res. 2017;66:959‐967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holecek M, Skopec F, Sprongl L. Protein metabolism in cirrhotic rats: effect of dietary restriction. Ann Nutr Metab. 1995;39:346‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gomes‐Marcondes MC, Tisdale MJ. Induction of protein catabolism and the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway by mild oxidative stress. Cancer Lett. 2002;180:69‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koohmaraie M, Kretchmar DH. Comparisons of four methods for quantification of lysosomal cysteine proteinase activities. J Anim Sci. 1990;68:2362‐2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holecek M, Kovarik M. Alterations in protein metabolism and amino acid concentrations in rats fed by a high‐protein (casein‐enriched) diet ‐ effect of starvation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:3336‐3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vodenicarovova M, Skalska H, Holecek M. Deproteinization is necessary for the accurate determination of ammonia levels by glutamate dehydrogenase assay in blood plasma from subjects with liver injury. Lab. Med. 2017;48:339‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nissen SL, Abumrad NN. Nutritional role of the leucine metabolite β‐hydroxy‐β‐methylbutyrate (HMB). J Nutr Biochem. 1997;8:300‐311. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holecek M. Branched‐chain amino acids and ammonia metabolism in liver disease: therapeutic implications. Nutrition. 2013;29:1186‐1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holecek M. Evidence of a vicious cycle in glutamine synthesis and breakdown in pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy‐therapeutic perspectives. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29:9‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nishikawa T, Bellance N, Damm A, et al. A switch in the source of ATP production and a loss in capacity to perform glycolysis are hallmarks of hepatocyte failure in advance liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1203‐1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yonamine CY, Teixeira SS, Campello RS, et al. Beta hydroxy beta methylbutyrate supplementation impairs peripheral insulin sensitivity in healthy sedentary Wistar rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2014;212:62‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holeček M. Branched‐chain amino acids in health and disease: metabolism, alterations in blood plasma, and as supplements. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018;15:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wijekoon EP, Skinner C, Brosnan ME, et al. Amino acid metabolism in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat: effects of insulin resistance and of type 2 diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82:506‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]